Fantasy Books

Women in SF&F Month: Pat Murphy

Today’s Women in SF&F Month guest is Pat Murphy! Her work includes the short stories in Women Up to No Good, the Philip K. Dick Award–winning collection Points of Departure, and the Nebula Award–winning novel The Falling Woman. Pat’s latest SF&F novel—her first in more than 20 years—is The Adventures of Mary Darling. This subversive retelling of Peter Pan and Sherlock Holmes focuses on Mary Darling—the mother of the children who flew away with Peter Pan and the niece of […]

The post Women in SF&F Month: Pat Murphy first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Spotlight on “My Name is Emilia del Valle” by Isabel Allende

In the spellbinding historical novel My Name is Emilia del Valle, a young writer journeys…

The post Spotlight on “My Name is Emilia del Valle” by Isabel Allende appeared first on LitStack.

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Patrick Murray – Who was N.V. Romero?

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

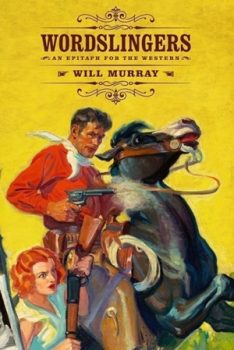

Will Murray has graced this column multiple times, and he has delved into a mystery or two. He’s got another one today, looking into a Pulp byline from the nineteen thirties that has gnawed away at him. And by golly, Will finally had enough! Read on…

____________________________________________

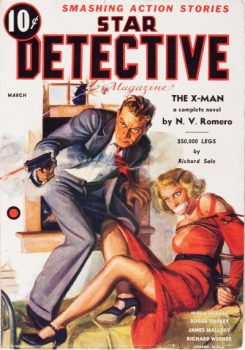

For literally decades, I’ve been intrigued and baffled by the cryptic byline N. V. Romero, which was emblazoned on the front cover of the March, 1937 Star Detective Magazine.

I don’t remember where or when I picked up that old Red Circle pulp magazine. Probably at a collector’s convention somewhere in the 1970s or 80s. It grabbed my attention because the cover-featured lead novel bore the intriguing title,

“The X-Man.”

That’s a coinage I did not think existed prior to Marvel Comics releasing X-Men #1 in 1963. So I grabbed it. I probably paid about five bucks. It was in reasonably good condition. And it was published by Martin Goodman, who later launched Marvel Comics.

This issue is comparatively rare. My copy has the distinction of having been photographed so the cover could appear in Les Daniels’ 1990 book, Marvel, as a weird precursor to The X-Men.

The story Stan Lee always told was that he wanted to call his new comic book about a school for teenaged superheroes, The Mutants. Publisher Goodman objected to the title on the grounds that young readers might not know the term, and Lee claimed to have suggested The X–Men instead. The X stood for extra power.

If that’s true, it’s quite a coincidence that Lee independently coined the term X-Man more than 25 years after Goodman published a cover story by that name. Lee’s memory was not always reliable, and it could be self-serving. It would not shock me if Goodman actually suggested the new title based on his memory of this cover story. Goodman had the reputation of being cover-conscious, believing that covers and titles were the chief elements that sold magazines.

“The X-Man” is the first-person account of Texas special investigator Daniel “Dash” Antonio of the border city of La Plaza District Attorney’s office. It’s a hardboiled story that gets a little metaphysical in spots. In the year of 1937, the G-man was the rising hero in America, and in the pulp magazines. When he was framed for murder, Antonio starts calling himself “the X-Man.“

“I’m on the spot,” he complains. “Instead of being a G-man, I’m an X-man. Dash Antonio, X-Man.”

The novel was credited to N. V. Romero. That byline was unfamiliar to me. So when pulp magazines began to be indexed in depth, and those indexes posted online, I eagerly looked up the name.

It appeared only once in the tens of thousands of pulp magazines that had been indexed and cross-referenced. And that was for the lead novel of the March 1937 issue of Star Detective.

I thought that exceedingly strange. True, inexperienced authors did sell the occasional yarn to pulp magazines, and never appeared again.

There was a self-described “rank amateur” Missouri writer named Vaughn Bryant who sold a story entitled “The Stalking Satan” to Secret Agent X in 1935. He credited the sale to his agent, Lurton Blassingame. The submission ran in the October issue as “The Wailing Skull.”

Bryant apparently only sold that one story––or at least his byline appeared only once in a pulp magazine. Well, it happens that Secret Agent X was a bottom of the barrel market. As was Star Detective Magazine. Fledgling pulpsters more easily broke into the pages of such titles, as opposed to Black Mask. And many who managed one sale never made another.

But the beginners who sold the odd pulp yarn usually wrote short stories. “The X-Man” was a full-length novel. This suggested a seasoned professional.

For years, I puzzled over that unfamiliar name. I often wondered, Was there a clue to Romero’s true identity concealed in his initials? Phonetically, N. V. sounded like “envy.” That was a dead end. The ethic last name was unusual for a pulp magazine, which shunned anything that didn’t sound unequivocally Anglo-Saxon. That, and the one-time use all but ruled out the possibility that it was a house name.

There was one clue. The novel was set in the fictional town of La Plaza, Texas. I reasoned that the author would probably be a Texas native. My initial thoughts ran to Eugene Cunningham of El Paso, Texas, who primarily wrote Westerns, but did other things. But I had no way of tying Cunningham to Romero. I also considered Margie Harris, a Houston native known for writing detective and gangster stories.

Until it occurred to me to jump onto Newspapers.com and punch in that mysterious byline, limiting the search to Texas newspapers.

The first thing that popped up was a letter to the editor of the El Paso Times bylined N. V. Romero. It was dated October 30, 1937.

My researcher’s antennae lifted and quivered.

I had confidently assumed that N. V. Romero was a pseudonym for some prolific pulpster who preferred to conceal his identity because he wrote for the lower-paying Goodman group. Could it be that there was an actual N. V. Romero, and that unusual byline did not in fact mask anybody previously known to the reading public?

Searching further, I found several more letters and a few poems printed the El Paso Times.

It was beginning to seem as if Mr. Romero was nobody other than an unknown author––but also kind of a national non-entity.

One 1933 reference suggested that he worked as a grocer and ran the R. Gomez grocery store in El Paso.

But I had yet to discover absolute proof that this was the nebulous author of The X-Man. I continued scrolling.

Then I came across this gem in the El Paso Times‘ “Around Here” column for March 18, 1937:

AUTHORS DETECTIVE NOVEL.

“It might be interesting to note,” writes M. S. Salcido, “that N. V. Romero, who writes such nice poetry for the Sunday Book Page, has a hard and fast detective novel featured on the cover of the Star Detective Magazine for March.”

Columnist H. S. Hunter added:

“Thanks for the tip. It’s good to know when an El Pasoan comes out with either novel or short story, or accomplishes worthwhile work any other line, for that matter, and this column welcomes a chance to give him a hand.’

There it was––conclusive proof! Mr. Romero was real and he was the actual author of that oddball lead novel.

I was rather chagrined. Decades before, I had written an article on the subject for Comic Book Marketplace where I confidently asserted that N. V. Romero was almost certainly a pseudonym for a hitherto-unidentified pulp author.

It just goes to show that even though one might be considered an expert in the pulp field, it’s dangerous to jump to conclusions.

It’s also a good thing I’m a stubborn and indefatigable researcher. And that I had a subscription to Newspapers.com.

As would be expected of someone who did not go on to literary fame, few facts can be gleaned about this obscure writer.

The author was a lifelong resident of the border town of El Paso, which is the obvious inspiration for La Plaza. A reference to La Plaza’s unnamed sister city across the Rio Grande River points to Juarez, which lies on the other side of the Rio from El Paso.

According to one newspaper notice, in 1931 Romero was admitted to Kalevala, the English Honor Society of the El Paso High School. Out of 76 students who applied, he was one of only 16 admitted. Admission was based on a writing sample. So his inclination toward writing may have started there. Even as a high schooler, he was known as N. V. Romero.

Apparently, Romero never married, or had children. He lived at the same El Paso address for decades. Other than the odd car accident, his name only appeared in print when he wrote a letter or poem for publication in the El Paso Times, which he did periodically, always signing it N. V. Romero.

Popping over to Ancestry.com, I discovered the secret of those mysterious initials. Romero’s 1940 Draft registration card listed his full name as Nicolas Varela Romero, age 25, born March 10, 1915. Under remarks about his fitness to serve was written: “Lame—on crutches.” I assume therefore that the Draft did not take him.

His birthdate means that Romero wrote “The X–Man’ when he was only 20 or 21.

According to Newspapers.com, Mr. Romero died on March 3, 1998 at the age of 82. His past occupations were given as architect, notary public and small business accountant. A 1940s census listed his occupation at the age of 30 as self-employed architect, working for different companies. As far as I’m able to determine, Romero never published another line of fiction in a national magazine for the rest of his days. At least, not under any variation of his real name.…

Bob on Red Circle:

Martin Goodman formed Red Circle Magazines in 1935, and Red Circle cranked out a plethora of low-grade Pulps, including:

All Star Fiction, All Star Adventures, Star Detective, Star Sports, Sports Action, Adventure Trails, Complete Adventures, Complete Western Book, Detective Short Stories, Complete Detective, Complete Sports, Best Sports, Mystery Tales, Top-Notch Western, Top-Notch Detective, Two-Gun Western, Six-Gun Western, Gunsmoke Western, Sky Devils, Western Short Stories, Cowboy Action Novels, Quick-Trigger Western, Modern Love, Wild West Stories & Complete Novel Magazine, Real Sports, Ka-Zar, and Marvel Science Stories.

Star Detective was a Weird Menace Pulp and ran for eleven issues in 1935-1938. It was changed to Uncanny Tales, lasted five more issues and that was the end. But it was a low-end Pulp, never publishing more than three issues in a year and not making any impact, short or long term.

Star did have some notable names, including Hugh B. Cave, L. Ron Hubbard, E. Hoffman Price, Paul Cain, Roger Torrey, and Richard Sale.

2025 (2)

Shelfie – Dashiell Hammett

Shelfie – Dashiell Hammett

Windy City Pulp & Paper Fest – 2025

2024 Series (11)

Will Murray on Dashiell Hammett’s Elusive Glass Key

Ya Gotta Ask – Reprise

Rex Stout’s “The Mother of Invention”

Dime Detective, August, 1941

John D. MacDonald’s “Ring Around the Readhead”

Harboiled Manila – Raoul Whitfield’s Jo Gar

7 Upcoming A (Black) Gat in the Hand Attractions

Paul Cain’s Fast One (my intro)

Dashiell Hammett – The Girl with the Silver Eyes (my intro)

Richard Demming’s Manville Moon

More Thrilling Adventures from REH

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (15)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Will Murray on Hammett Didn’t Write “The Diamond Wager”

Dashiell Hammett – ZigZags of Treachery (my intro)

Ten Pulp Things I Think I Think

Evan Lewis on Cleve Adams

T,T, Flynn’s Mike & Trixie (The ‘Lost Intro’)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part I (Breckenridge Elkins)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part II

William Patrick Murray on Supernatural Westerns, and Crossing Genres

Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘Getting Away With Murder (And ‘A Black (Gat)’ turns 100!)

James Reasoner on Robert E. Howard’s Trail Towns of the old West

Frank Schildiner on Solomon Kane

Paul Bishop on The Fists of Robert E. Howard

John Lawrence’s Cass Blue

Dave Hardy on REH’s El Borak

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (7 )

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (21)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (32)

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Phantom Crook (Ed Jenkins)

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘The Shrieking Skeleton’

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

The Black Mask Dinner

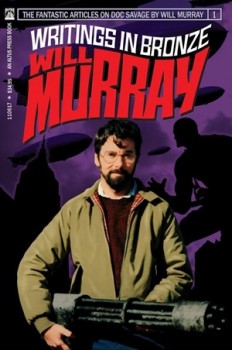

There are some outstanding names in the ‘New Pulp’ field, but William Patrick Murray’s probably stands above them all. Along with Doc Savage, Will has written Tarzan and The Spider. And he’s quite the Sherlock Holmes writer. Short stories, comic books, radio plays, nonfiction essays and books – Murray has done it all. He created The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl for Marvel Comics, and his collection of essays on Doc Savage, Writings in Bronze, is a must read. I love a good book introduction, and Murray has written some fine ones for Steeger Books. Visit his website Adventures in Bronze.

There are some outstanding names in the ‘New Pulp’ field, but William Patrick Murray’s probably stands above them all. Along with Doc Savage, Will has written Tarzan and The Spider. And he’s quite the Sherlock Holmes writer. Short stories, comic books, radio plays, nonfiction essays and books – Murray has done it all. He created The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl for Marvel Comics, and his collection of essays on Doc Savage, Writings in Bronze, is a must read. I love a good book introduction, and Murray has written some fine ones for Steeger Books. Visit his website Adventures in Bronze.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars and founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

You can definitely ‘experience the Bobness’ at Jason Waltz’s ’24? in 42′ podcast.

Review: A Song of Legends Lost by M.H. Ayinde

Buy A Song of Legends Lost

FORMAT/INFO: A Song of Legends Lost was published in the UK on April 8th, 2025, and will be published in the US on June 3rd, 2025. It is 592 pages long and available in paperback, ebook, and audiobook.

OVERVIEW/ANALYSIS: Everyone knows that only those of noble blood can invoke the ancestors, can call their spirits back to the mortal plane to fight in the wars against the greybloods. Or at least, that's what everyone thinks. But when a young woman in the slums summons a spirit, it sets off a chain reaction of events that will shift the Nine Lands forever. As families fight to determine the fate of the kingdom, one little detail slips through the cracks: not every spirit summoned is an ancestor.

A Song of Legends Lost is a truly unique science-fantasy story that will engross you as it keeps you guessing. It will be tempting for many of you to start this story and within a few chapters proclaim, "I know what's going on!" I certainly did that and I'm here to assure you that, like me, you will be wrong. This blend of magic and technology still has me (pleasantly) confused as to how it all ties together, as we only get a peek behind the curtain by the end of this first book.

The story immediately jumps into some bad situations with multiple characters, plunging you into the middle of things as you meet them. While a few POV characters stay the length of the book, some only stick around for chunks at a time, with the cast of POV characters changing as the story switches from Part 2 to Part 3, etc. This gives us a fairly wide view of the events that are playing out across the kingdom. The author does a good job overall of investing you in the characters, but given how much you jump around, I did occasionally find myself emotionally distanced from some characters more than others.

This is also a story that is working on two levels. On the surface you have the very real, sometimes deadly, political posturing between the monarchy, the powerful religious monks, and the noble families. But there is also a whole second layer of characters pulling strings for completely different reasons. To most, this is about protecting their power and protecting the Nine Lands from the dangerous graybloods. But to others, these power struggles are masking a completely different game. We don't know fully what's going on by the end of things, just that we are still in the dark about quite a lot.

That's where this story may be a bit frustrating for some. We only have a tantalizing glimpse of what's truly going on, with much mystery still to be unpacked in the subsequent sequels. Personally, there is plenty of adventure and growth to be found just in this book alone, but I did plead a little bit at the end to please give me just a liiiittle more detail of what's really going on? Please?

CONCLUSION: But in the end, that's while I'll be back for the sequel to A Song of Legends Lost. The author is clearly just getting started and I am ready to go along for the ride (especially after one especially juicy POV in the epilogue). If you're looking for something fresh and original to dive into, I wholly recommend checking out this story.

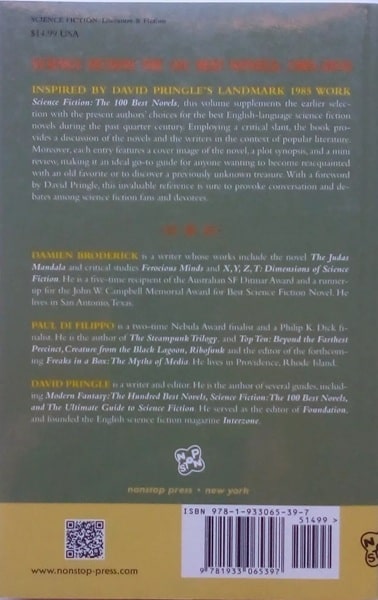

Damien Broderick, April 22, 1944 – April 19, 2025

Damien Broderick

Damien Broderick

Australian writer, editor, and critic Damien Broderick has died, April 19, 2025, just a few days short of his 81st birthday. He died peacefully in his sleep after a long illness. He is survived by his wife and occasional collaborator Barbara Lamar.

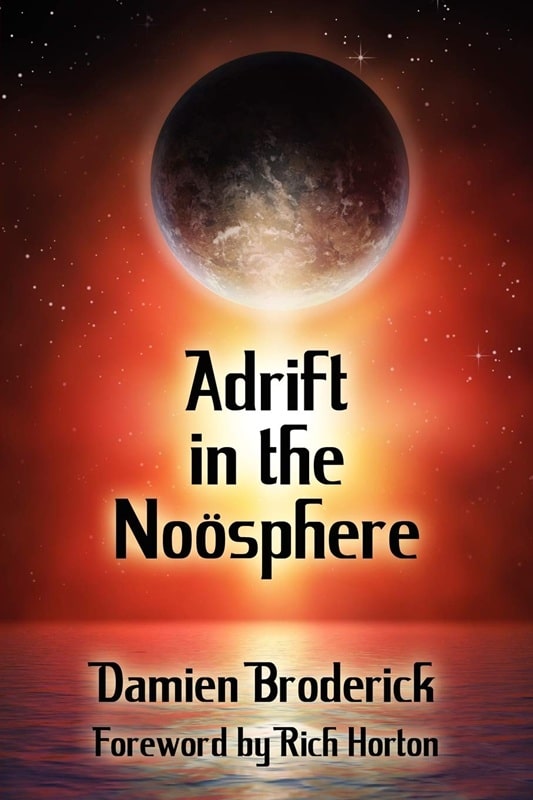

I had known Damien quite well online for decades, including interactions in newsgroups and on mailing lists as well as personal correspondence. We met only once, at the World Fantasy Convention in 2017, in San Antonio, TX, where Damien lived at that time; and we had a nice if brief conversation. Damien was showing signs of physical frailty at the time but was still mentally sharp. I had the honor of writing the foreword to his 2012 collection Adrift in the Noösphere, and to reprint a couple of his excellent short stories.

Adrift in the Noösphere (Borgo Press, April 2012)

Damien Broderick was born April 22, 1944, in Melbourne, Australia. He began publishing at the age of 20 with “The Sea’s Furthest End” in the first volume of John Carnell’s original anthology series New Writings in SF.

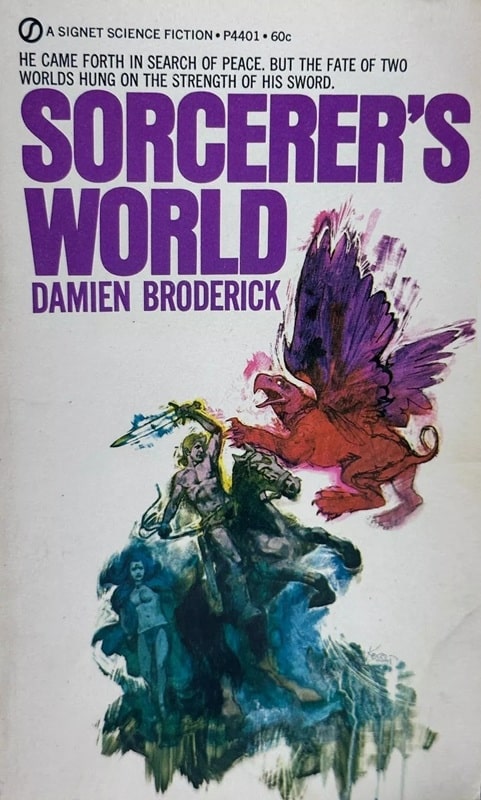

His first novel, Sorcerer’s World, appeared in 1970 but didn’t gain much notice. (Perhaps deservedly so – I found it less than successful myself and Damien once admitted to me that he regretted some fairly juvenile tricks he played in the novel – he extensively revised it in 1985 as The Black Grail.)

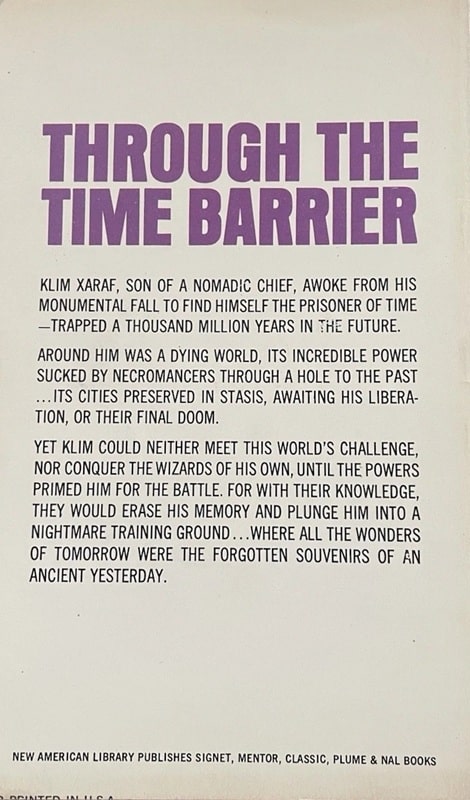

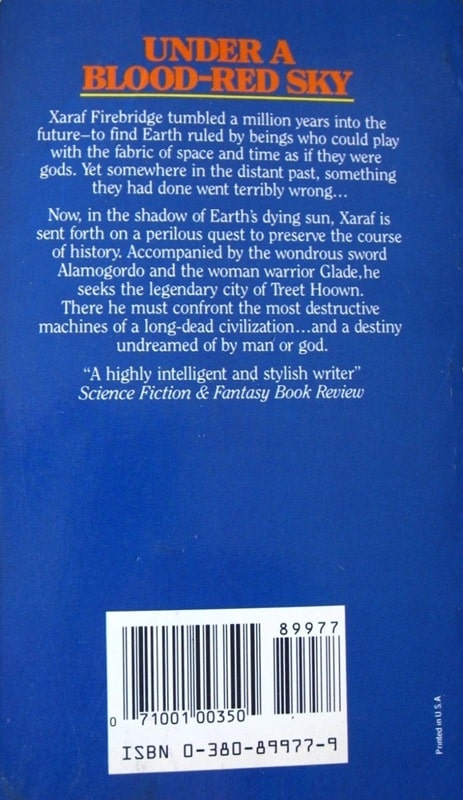

Sorcerer’s World (Signet, October 1970) and The Black Grail

(Avon, September 1986). Covers by Sanford Kossin and Luis Royo

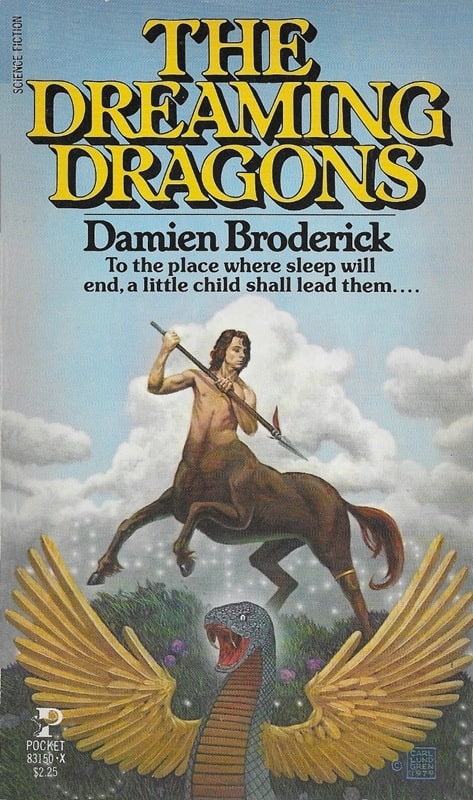

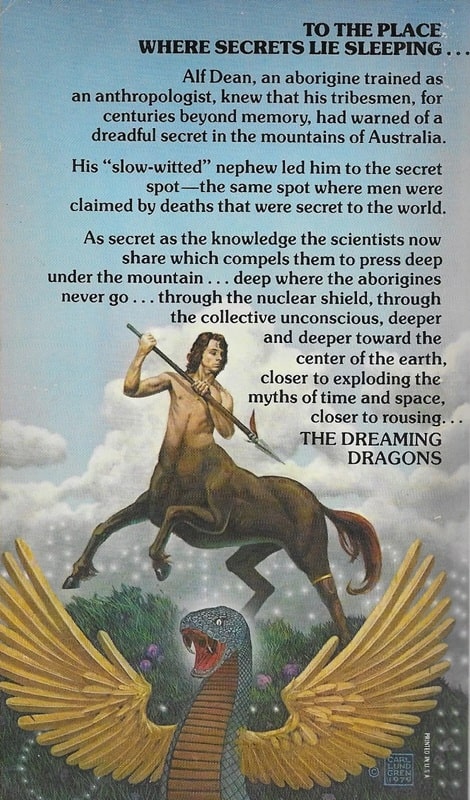

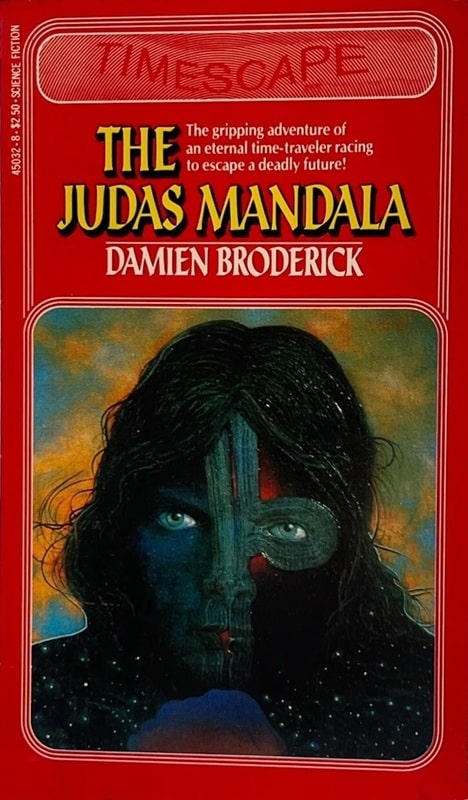

Indeed, Broderick was fond of radically reworking and improving his stories – he revised his first story, “The Sea’s Furthest End,” twice; and also revised The Dreaming Dragons, which won a Ditmar on its first appearance in 1980, as The Dreaming in 2001.

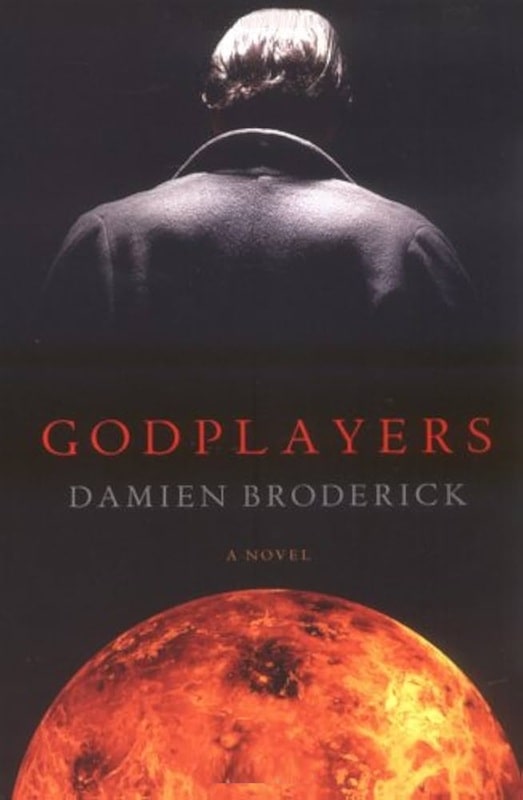

The Dreaming Dragons (Pocket Books, November 1980) and The Judas Mandala

(Timescape, October 1982). Covers by Carl Lundgren, uncredited

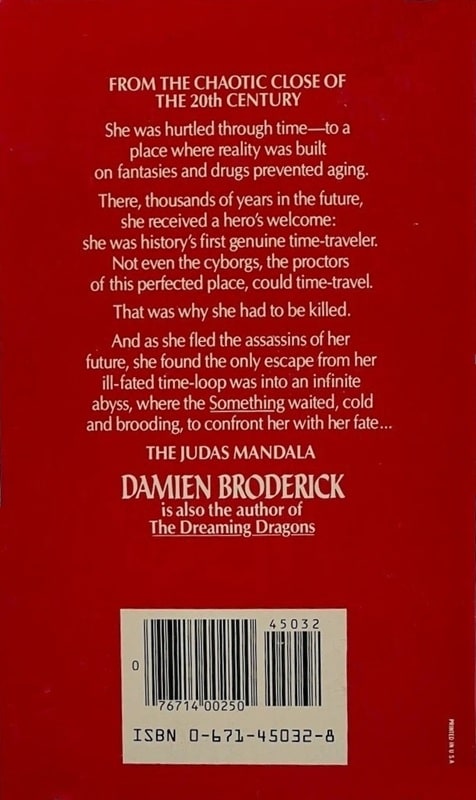

Broderick began to gain wider notice with The Dreaming Dragons, and subsequent novels including The Judas Mandala (1982), The White Abacus (1997), and the impressive diptych comprising Godplayers (2005) and K-Machines (2006) earned him much praise, and eventually four Ditmar awards and three Aurealis awards (the two most prominent Australian SF awards.) He was granted the A. Bertram Chandler Award for Outstanding Achievement in Australian Science Fiction in 2010.

Godplayers and K-Machines (Thunder’s Mouth Press,

May 2005 and March 2006). Covers by David Riedy

He also collaborated on a number of novels with Rory Barnes, not all of which were SF – I was impressed by a rather madcap contemporary crime novel called I’m Dying Here (2009) – and with Barbara Lamar he wrote Post Mortal Syndrome (2011). His final “collaborations” were two novels rather radically revising early works by the late John Brunner: Threshold of Eternity (2017) and Kingdom of the Worlds (2021).

Broderick was also a first-rate writer of short fiction. I was profoundly impressed by “The Ballad of Bowsprit Bear’s-Stead (1980) and “The Magi” (1982), and then by a sequence of remarkable work in the 21st century, with several of these stories pastiches of major earlier SF work. The best of this late flowering are “Under the Moons of Venus,” “This Wind Blowing, and This Tide,” “The Qualia Engine,” and “The Beancounter’s Cat”; and in my view Broderick’s late short fiction deserves a closer look.

Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction (Routledge, 1995) and

X, Y, Z, T: Dimensions of Science Fiction (Borgo Press, January 2004).

Covers by Alan Craddock and Anders Sandberg

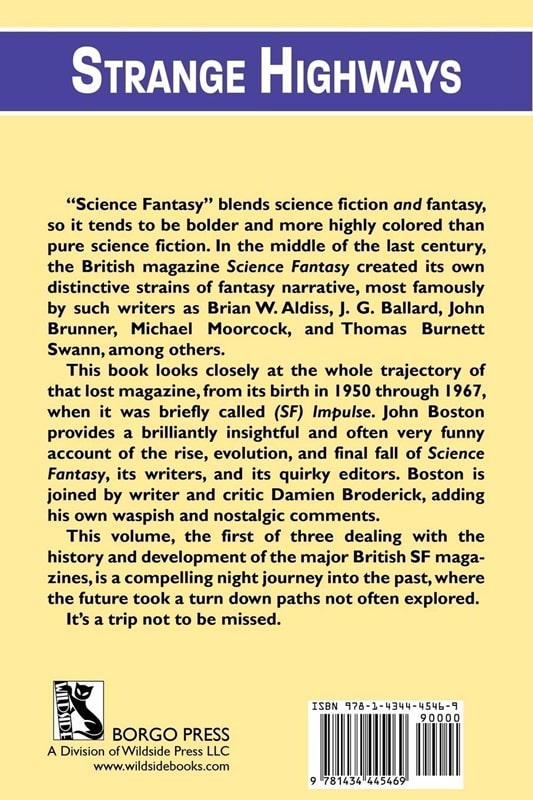

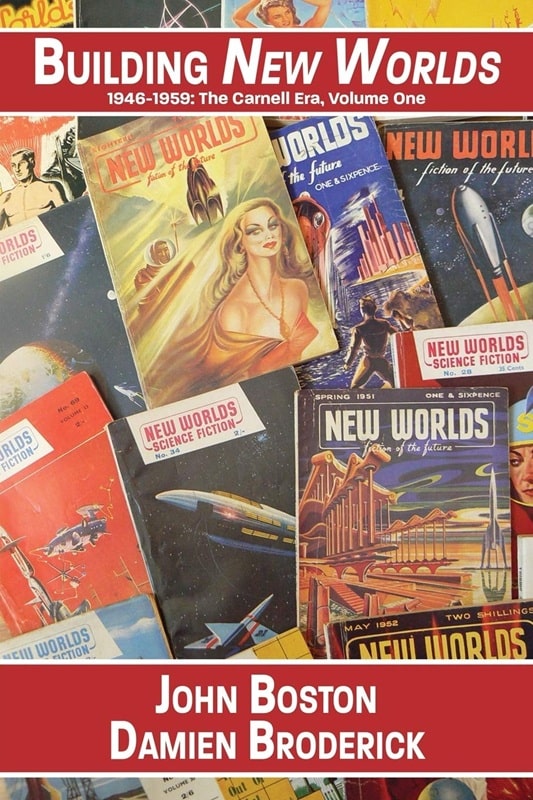

He has also written extensively in SF criticism, and in speculative science. Major critical works include Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction (1995); Transrealist Fiction: Writing in the Slipstream of Science (2000); and X, Y, Z, T: Dimensions of Science Fiction (2004); as well as, with John Boston, a series of books detailing the history of John Carnell’s seminal UK magazines New Worlds and Science Fantasy issue by issue.

His science books include most notably The Lotto Effect: Towards a Technology of the Paranormal (1992); The Spike: Accelerating into the Unimaginable Future (1997); and Ferocious Minds: Polymathy and the new Enlightenment (2005).

Strange Highways: Reading Science Fantasy, 1950-1967 and Building New Worlds,

1946-1959: The Carnell Era, Volume One (Borgo Press, January 3 and January 29, 2013)

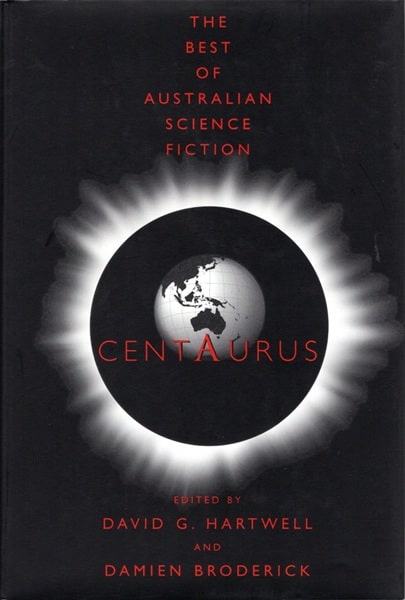

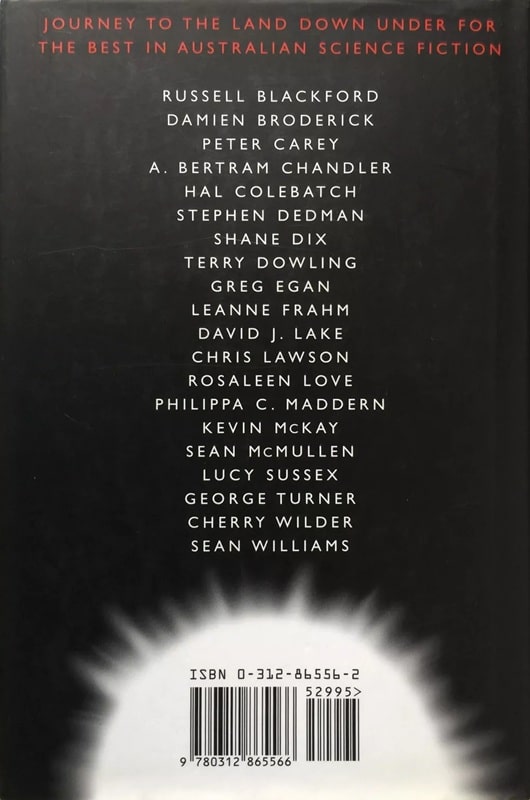

He made contributions as fiction editor of the Australian science magazine Cosmos, and as a prolific anthologist. His anthologies include The Zeitgeist Machine (1977), Earth is But a Star (2001), and, with David Harwell, Centaurus: The Best of Australian Science Fiction (1999).

Damien Broderick was an outstanding science fiction writer – and, to my mind, a somewhat underappreciated one. He was a tireless advocate of Australian SF, in both his anthologies and his critical work. He was an intriguing and rather iconoclastic science writer, very interested in the far future and in very speculative scientific ideas, including paranormal powers. His scientific interests, not surprisingly, also inform his science fiction, much to its benefit (in the The Judas Mandala he seems to have coined the term “Virtual Reality.”)

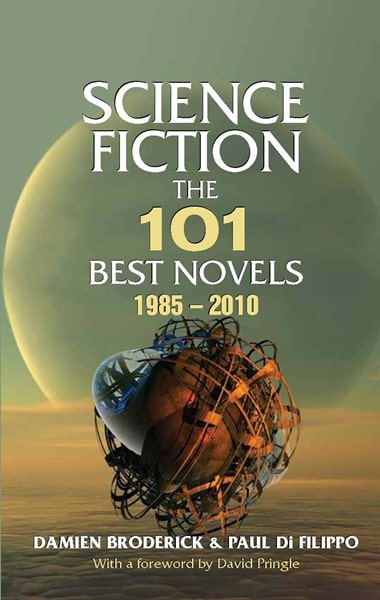

Striped Holes (Avon, November 1988), Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010,

with Paul Di Filippo (Nonstop Press, 2012), and Centaurus: The Best of Australian Science Fiction,

with David G. Hartwell (Tor, July 1999). Covers by Bryn Barnard, Luis Ortiz, and Peter Lutjen

His range was broad – he wrote fantasy and crime fiction as well as SF, and his fiction could be very funny as well as very dark, sometimes at the same time. I was privileged to know him as well as I did, and I will miss him.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a Retro-Review of the August 1961 issue of Fantastic magazine. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over 200 articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Women in SF&F Month: Week 4 Schedule & Week in Review

The fourth week of Women in SF&F Month starts tomorrow, with four new guest posts and a book giveaway coming up this week. Thank you so much to last week’s guests for their fantastic essays! Before announcing the schedule, here are last week’s guest posts in case you missed any of them. All guest posts from April 2025 can be found here, and last week’s guest posts were: “The Long and the Short of It” — A. G. Slatter (The […]

The post Women in SF&F Month: Week 4 Schedule & Week in Review first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Book Review: Cold Eternity by S.A. Barnes

I received a review copy from the publisher. This does not affect the contents of my review and all opinions are my own.

Mogsy’s Rating: 3.5 of 5 stars

Genre: Science Fiction, Horror

Series: Stand Alone

Publisher: Nightfire | Macmillan Audio (April 8, 2025)

Length: 293 pages | 9 hrs and 38 mins

Author Information: Website

There’s just something irresistible about a haunted-in-space story, which is probably why I always come back to S.A. Barnes. While none of her books have quite crossed that line into “phenomenal” territory for me, I can always count on her to deliver a reliably solid and entertaining experience.

In Barnes’ newest novel Cold Eternity, the premise is immediately intriguing. The story follows Halley Zwick, though she’s been known by multiple names. A woman with a complicated past trying to outrun her overbearing family and a political scandal, she is forced to accept a shady, criminally low paying job just to stay under the radar. The role itself is easy enough, requiring Halley to press a button every few hours and do some rounds. However, it is situated aboard a derelict barge in space known as the Elysian Fields. Originally built to preserve the cryogenically frozen bodies of the rich and powerful with a hope that future medical advancements will allow or their revival, the ship was even repurposed to be a museum for a time but is now nothing but a decaying relic left floating in the void.

Right away, Halley is warned by her mysterious and insufferable boss Karl that she will be expected to perform her duties independently, and that there are areas of the ship that are absolutely off-limits. Preferring to work alone anyway, Halley takes no issue with following his instructions—until strange things start happening on Elysian Fields that go beyond the typical quirks of an aging, crumbling ship. Unexplained noises echo through the emptiness, and Halley thinks she catches sight of someone or something in the shadowed corridors—even though, as far as she knows, the only living souls aboard are Karl and herself, with everyone else locked away forever in cryogenic sleep.

Following in the footsteps of her previous novels Dead Silence and Ghost Station, the author returns with another tense, atmospheric thriller that leans hard into the themes of isolation, paranoia, and rogue technology. Once more, Cold Eternity is packed with unsettling imagery and claustrophobic scenarios which add to the mounting dread. One of Barnes’ greatest strengths lies in her ability to craft eerie, immersive scenarios that have an almost cinematic quality to them. In fact, as someone who recently watched the latest Alien movie Romulus, I could help but draw some inevitable parallels, from the derelict spaceship setting to the glimpses of horrifying monsters lurking in the dark.

Still, although the book had plenty to keep me turning the pages, there were a handful of reasons that kept it from being truly memorable. For one, the pacing felt uneven, with the story taking its sweet time unraveling the central mystery. Without revealing too many spoilers, onboard the Elysian Fields is a cryogenically frozen individual whose memory has been preserved, and with whom Halley has a history. However, this relationship is never explored to my satisfaction, remaining largely surface-level. Similarly, hints about Halley’s troubled past are scattered throughout the book but are mostly withheld until the final stretch, when all is revealed in one big dump. While I typically appreciate a good slow burn when it’s building toward something impactful, here the narrative felt less like a careful calculation and more like stalling.

Another thing that tripped me up was some of the repetitiveness in the plot. The cycle of Halley’s routine which amounted to making rounds, hearing strange noises or seeing strange things, then questioning her sanity became a bit of a slog. I get that readers are supposed to sympathize with the protagonist’s growing paranoia and exhaustion, but the way it was handled made large portions of the novel’s middle section feel unnecessary or redundant. I found myself wishing for more variety in the horror and thrills, or at least some deeper insights into the ship’s macabre history during some of the quieter stretches.

But overall, did I enjoy the book? The answer is yes, which is the most important part. Although not flawless, Cold Eternity is undeniably entertaining and has its fair share of spooky moments. I certainly ate it up in a very short amount of time. Like I said, even though the story is unlikely to stay with me for long, I knew I could count on it for a fun, solid read.

![]()

![]()

Tubi Dive, Part II

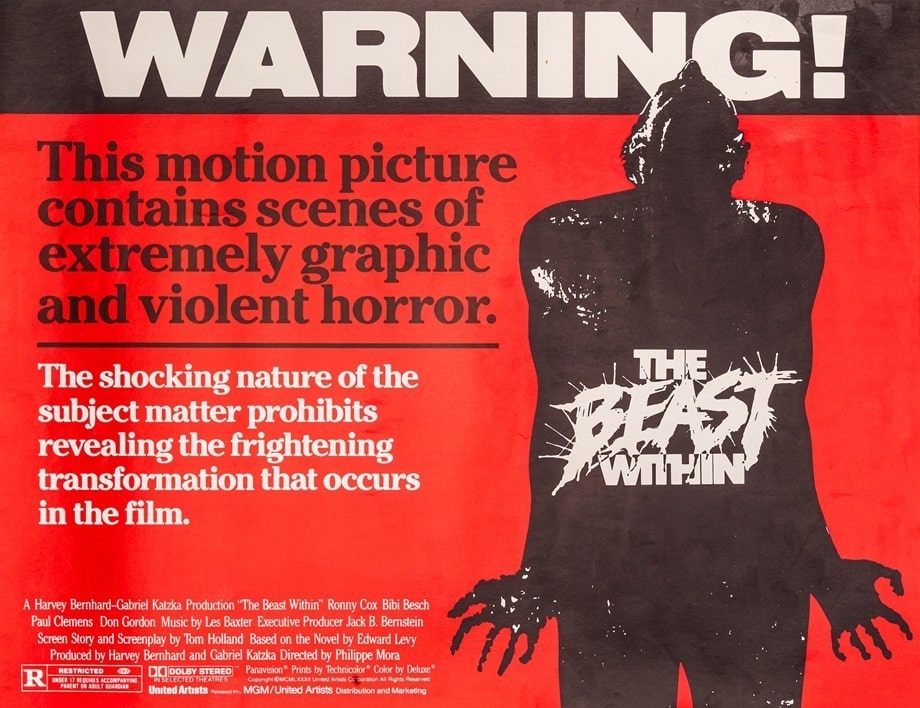

The Beast Within (United Artists, February 12, 1982)

The Beast Within (United Artists, February 12, 1982)

50 films that I dug up on Tubi.

Enjoy!

The Beast Within (1982)This crusty classic from the early 80s exemplifies the beautiful state of the horror genre at that time. This is one of the first writing credits for Tom (Fright Night, Chucky) Holland, and he wears his influences on his sleeve. HPL is well with the theme (evil possession, familial curses) and a couple of character names (Dexter Ward, the Curwins), but for me the primary influence was Hammer’s Curse of the Werewolf (a woman is raped by a foul individual, her subsequent offspring has a hard time of it), although this film could easily be called Curse of the WereCicada — such is its nutty premise.

The young man who has a ‘beast within’ seems to be possessed by his criminal father (later to be echoed in Chucky?), is played quite well by Paul Clemons in essentially a duo role, and anything with Ronny Cox in it is automatically a hit in my book. That said, the film is justifiably derided for some of the acting, and the entire storyline, but it’s a glorious smorgasbord of sweaty, sleazy characters and over-the-top latex bladder effects.

6/10

The Dunwich Horror (American International Pictures, January 14, 1970)

The Dunwich Horror (1970)

The Dunwich Horror (American International Pictures, January 14, 1970)

The Dunwich Horror (1970)

Yes, I can hear some of you clutching at your pearls as I write this, but barring a couple of clips here and there, I had never actually seen this one before.

As Lovecraft adaptations go, I guess you could say this is one of the most faithful, what with familiar names and places and ‘Yog-Sothoth’ being yelled approximately 300 times, but it is a far cry from the original source material.

Corman must have read the description of Wilbur Whateley (“goatish”) and interpreted that as ‘horny,’ because this version of WW just wants one thing, and that’s Sanda Dee naked on a sacrificial shagging stone. This is Dee’s first ‘mature’ film, and I wasn’t impressed — she’s a bit bland in this, however, Dean Stockwell as Wilbur is amazing. Now there is an actor who is FULLY committed. The monster in the attic is a bit of a letdown, depicted more like a colour out of space than the sort of tentacled beastie that butters my toast, but the production design is rather lovely, and there are some great matte paintings on show.

Fun for viewers who like gibbering madness and drugged tea.

6/10

Empire of the Ants (American International Pictures, July 29, 1977)

Empire of the Ants (1977)

Empire of the Ants (American International Pictures, July 29, 1977)

Empire of the Ants (1977)

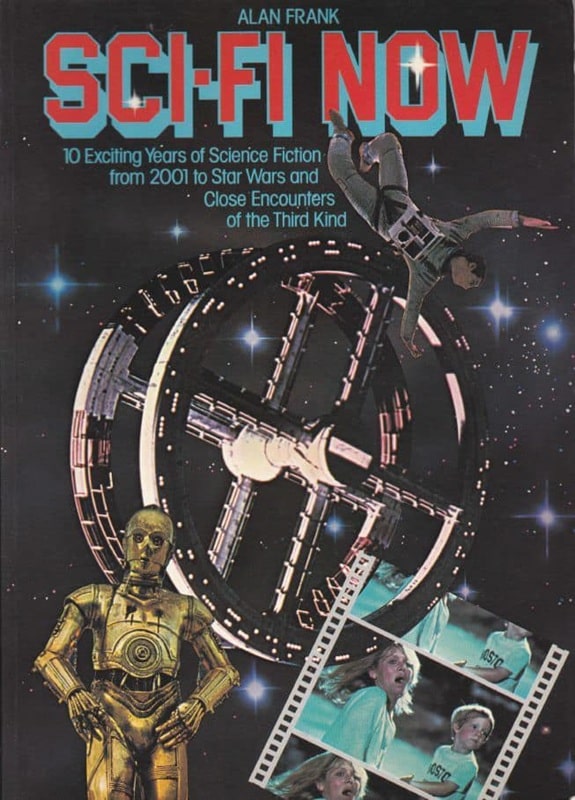

During that heady time in the mid 70s when so many creature features came out (Jaws, Grizzly, White Buffalo, King Kong et al), this one popped out at the tail end of the boom. I’m a sucker for ant movies (Phase IV, Naked Jungle), and this movie had assumed near mythical status for me, based on a few late-night clips on TV when I was a youngster, and a black and white picture of Joan Collins looking unperturbed, from one of the books that shaped my youth, Sci-Fi Now.

Sci Fi Now by Alan Frank (Octopus, January 1, 1978),

containing the classic still of Joan Collins in Empire of the Ants

Watching it now, as a bitter old man, it’s a bit rubbish.

Directed by Bert I. Gordon, from the H. G. Wells story, it’s a cheesy romp, and set mostly in the Florida Everglades. In the last third of the film the setting moves to a pheromone-controlled town, and this would have made a much better film, however, the preceding snooze-fest in the woods is a bit of a slog. Dodgy effects and horrible sound effects are the icing on this ant-ridden cake.

5/10

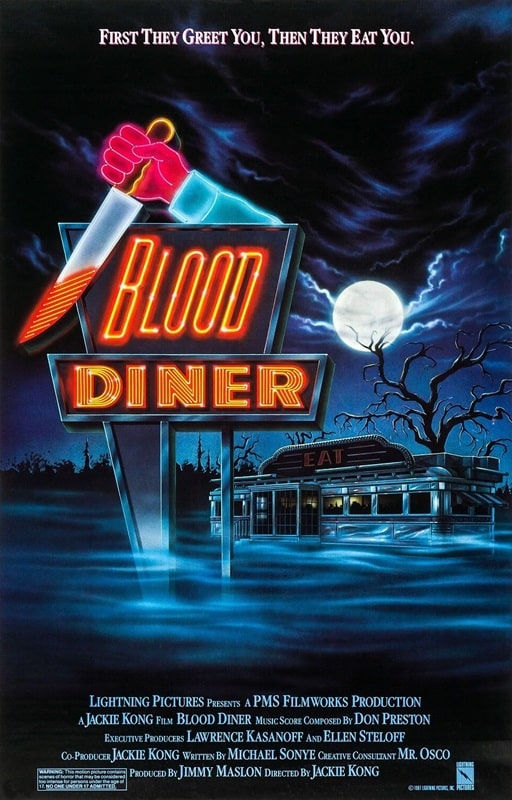

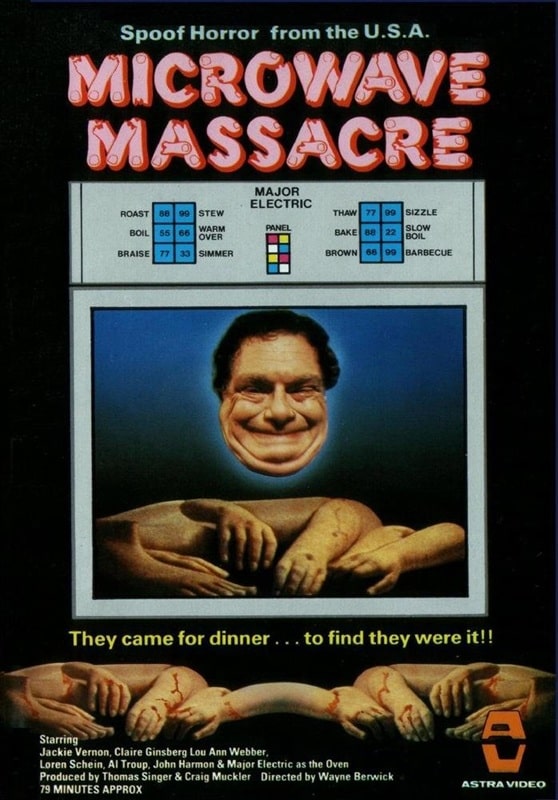

Blood Diner (Lightning Pictures, July 10, 1987)

and Microwave Massacre (Reel Life Productions, 1979)

Regrets, I’ve had a few. Usually after watching a sharksploitation film full of bad actors. However, the only regret I have after watching this stunningly bonkers horror comedy from Jackie Kong, is that I didn’t see it in 1987, thus depriving me of 36 years of annual re-watches.

I’m not sure how she did it, but Kong tapped into the under-developed brain of a 14-yr-old boy and made the perfect film.

It’s ludicrous, gory, offensive, daft as a badger on a hang glider, and quite brilliant — I wholly get why it has achieved such a cult status.

The abysmal acting is just the icing on the cake in this story of a couple of dumb brothers trying to resurrect an ancient, evil goddess by murdering women and using their internal organs in a ritual. All other body parts are served in their diner. As is befitting a mid-80s horror romp, this is full of nudity, sexism, practical dismemberments, and banging tunes.

Highlights include a deep-fried head, a funk band brass section dressed as Hitler, a brain in a jar, death by stalactite, an exploding quiff, an extremely long sequence of someone getting repeatedly run over, someone in a Ronald Reagan mask shooting up a studio full of topless cheerleaders, and the perviest detective you’ll ever meet.

It’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre meets The Naked Gun.

Insane.

10/10

Microwave Massacre (1979)An oddball flick, this does tangentially feature a microwave, but no massacres. To be honest, I’m still coming to terms with whether or not I enjoyed it. The film is supposed to be a farce, but its humor is neither insightful, nor funny. If anything, it plays like an early 70’s smut flick on quaaludes. The acting is amateur at best, and the women are portrayed in only two ways, sexual playthings, or screeching harpies. All are eaten though. The lead character, Donald, is played by Jackie (Frosty the Snowman) Vernon in the most laid back style I have ever witnessed. It’s as if he had just wandered into each scene and someone whispered a line to him, which he would repeat with zero emotion. All very strange, even more so when he turns to camera and just stares at us.

The horror elements are fairly cheesy, as are the nudity scenes (although the first one we get is more disturbing than cheesy), but the ACME Rubber Hand Co. must have made a killing that year.

One for true purveyors of weird stuff.

5/10

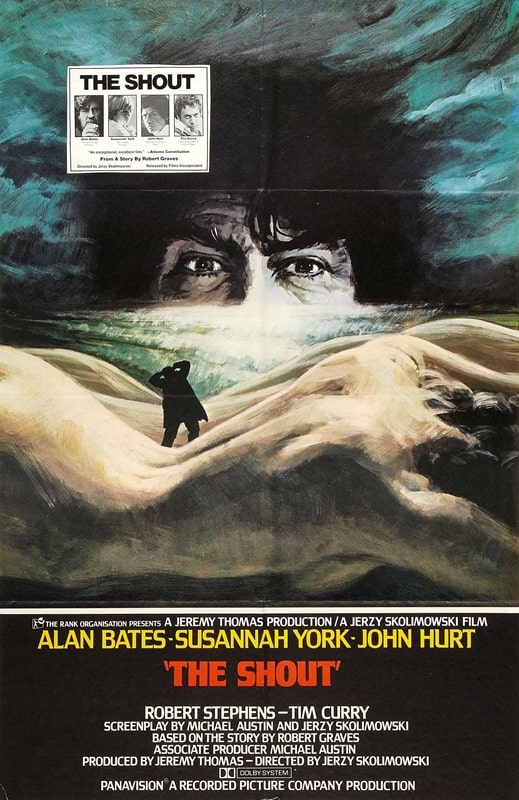

The Shout (Rank Film Distributors, June 16, 1978)

and The Suckling (Hypercube, September 24, 1990)

It’s a funny old world, ain’t it. How a film slips by a purveyor of horror, especially British horror, like myself never fails to intrigue me — yet here we are.

The Shout is not only based on a short story by Robert Graves, but it won a top award in Cannes that year, is a classic bit of British Folk(ish) horror in the same vein as The Wicker Man, and it had eluded me all these years. Now, thanks to Tubi’s unrivalled collection, I have finally seen it, and it’s staggeringly good.

It helps that you got the likes of Alan Bates (at the height of his dangerously sexy period), John Hurt, Susannah York, and every excellent English character actor including fresh-faced Tim Curry and fresher-faced Jim Broadbent in the cast. The story is fairly bonkers — a stranger (Bates) inserts himself into the cozy cottage life of Hurt and York, and proceeds to take over, cuckolding Hurt and claiming York through aboriginal sorcery. Yep, aboriginal sorcery. Apparently he had lived in Australia for 18 years, fallen in with an aboriginal shaman, and learned some dark magics, not least of all the ability to kill a person with a single shout.

The story is bookended by a cricket match between the inmates of an asylum and their carers, and the characters are all connected by this strange game.

It also helps that the exteriors were all shot in Devon, and that the direction and editing are super-interesting, bordering on experimental. The director, Jerzy Skolimowski, wisely keeps many events in the film ambiguous, keeping the viewer on their toes and questioning everything.

Highly recommended if you like 1970s British horror, or modern-day equivalents by the likes of Ben Wheatley, Ari Aster or Robert Eggers.

10/10

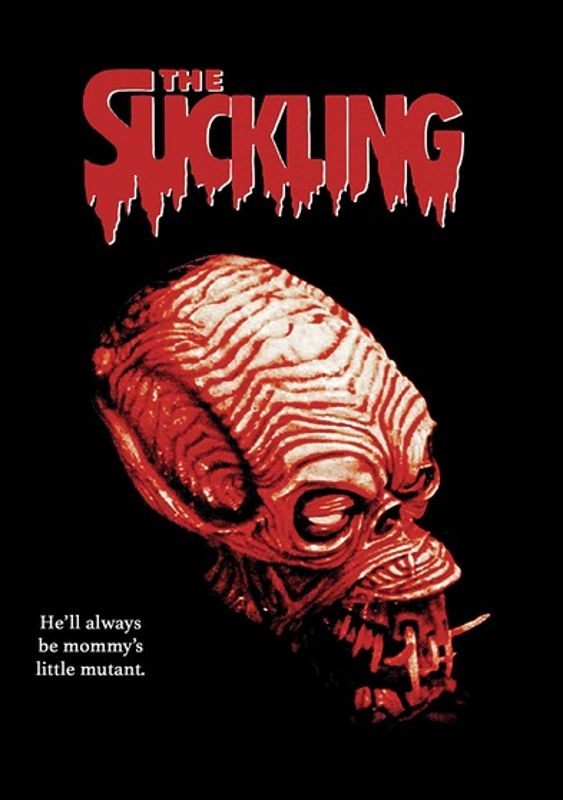

The Suckling (1990)Take a look at the official synopsis, and then decide if you want to carry on reading:

When a pregnant woman goes to an illegal abortion clinic doubling as a brothel, her aborted mutant fetus sets out on a violent rampage.

Still here?

Yes, this one is offensive as all hell. The premise is barking mad, the acting is dire (more on this later) and the direction is all wrong, and yet… and yet I found myself laughing so much at this film that I’m loath to give it a bad score, even though it deserves it. The laughs, of course, were unintentional and only caused by terrible lines and delivery of said lines. About 15 minutes in, I suddenly realized why I was enjoying it so much; it’s like a feature-length episode of Garth Marenghi’s Dark Place — there’s even an actor who not only looks like Richard Ayoade, but delivers his lines exactly like Dean Learner.

The fast-growing fetus monster is a slightly goofier version of Rawhead Rex (if that’s possible), and the actual kills are mostly off-screen — I can’t help wondering if this was an edited version I saw.

A particular highlight is the foley added to the film. Every object, ceiling fan, footstep, and door kick is given a loudly incorrect sound effect — you have to watch it just for this.

Bottom line — it’s terrible, awful acting, ridiculous premise, silly fx.

Highly recommended.

6/10

Previous Murkey Movie surveys from Neil Baker include:

Tubi Dive, Part I

What Possessed You?

Fan of the Cave Bear

There, Wolves

What a Croc

Prehistrionics

Jumping the Shark

Alien Overlords

Biggus Footus

I Like Big Bugs and I Cannot Lie

The Weird, Weird West

Warrior Women Watch-a-thon

Neil Baker’s last article for us was Part I of Tubi Dive. Neil spends his days watching dodgy movies, most of them terrible, in the hope that you might be inspired to watch them too. He is often asked why he doesn’t watch ‘proper’ films, and he honestly doesn’t have a good answer. He is an author, illustrator, teacher, and sculptor of turtle exhibits. (AprilMoonBooks.com).

Don’t Go into the Nursery! 6 Haunting Novels with Scary Children

If you are looking for a chilling read that will make you question the innocence…

The post Don’t Go into the Nursery! 6 Haunting Novels with Scary Children appeared first on LitStack.

Junkyard Cats - Book Review

Junkyard Cats (Junkyard Cats #1)by Faith Hunter

Junkyard Cats (Junkyard Cats #1)by Faith HunterWhat is it about:After the Final War, after the appearance of the Bug aliens and their enforced peace, Shining Smith is still alive, still doing business from the old scrapyard bequeathed to her by her father. But Shining is now something more than human. And the scrapyard is no longer just a scrapyard, but a place full of secrets that she has guarded for years.

This life she has built, while empty, is predictable and safe. Until the only friend left from her previous life shows up, dead, in the back of a scrapped Tesla warplane, a note to her clutched in his fingers - a note warning her of a coming attack.

Someone knows who she is. Someone knows what she is guarding. Will she be able to protect the scrapyard? Will she even survive? Or will she have to destroy everything she loves to keep her secrets out of the wrong hands?

What did I think of it:I was warned by a friend that this was a weird series, still I was curious enough to give it a try.

And I what she meant.This is a futuristic world with lots of freaky stuff, so if you're not into freaky science SciFi skip this series.

Still, I had a good time with this book.There was a bit too much fighting at times. I would have liked it better if there was a better balance between the tense action and more relaxed moments.But all in all this was an interesting and intriguing read. I really liked Shining and her employee/friend Matteo. And of course there are the junkyard cats!

There is a lot going on and explained in this book, and maybe Hunter chose to get in so much action to make all the explaining less boring (which it wasn't imo).By the end it's clear what Shining's next step will be, and I will get my trotters on the next book to see where this whole series will lead to.

Why should you read it:It's an intriguing Futuristic Read.

Women in SF&F Month: The Essential Patricia A. McKillip Cover Reveal

For Women in SF&F Month today, I’m revealing the cover of The Essential Patricia A. McKillip—and giving away two galleys of the 30th anniversary edition of her fantasy novel The Book of Atrix Wolfe! This is an honor since I love her writing, from the magic and beauty of her prose to the wit and wisdom that shines through her stories. She is the author of two of my favorite novels, The Changeling Sea and The Forgotten Beasts of Eld, […]

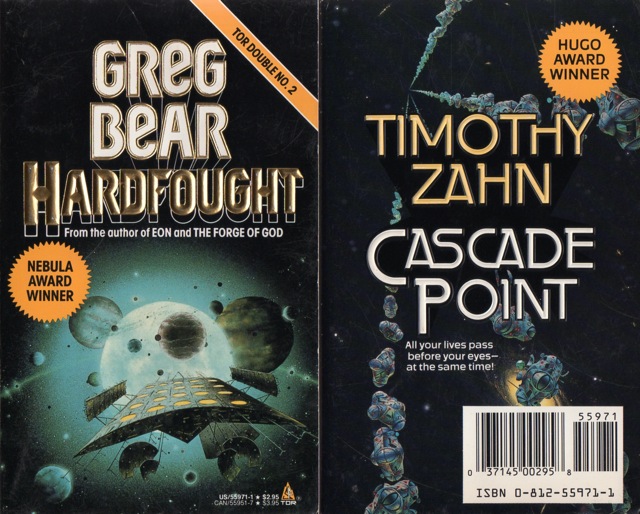

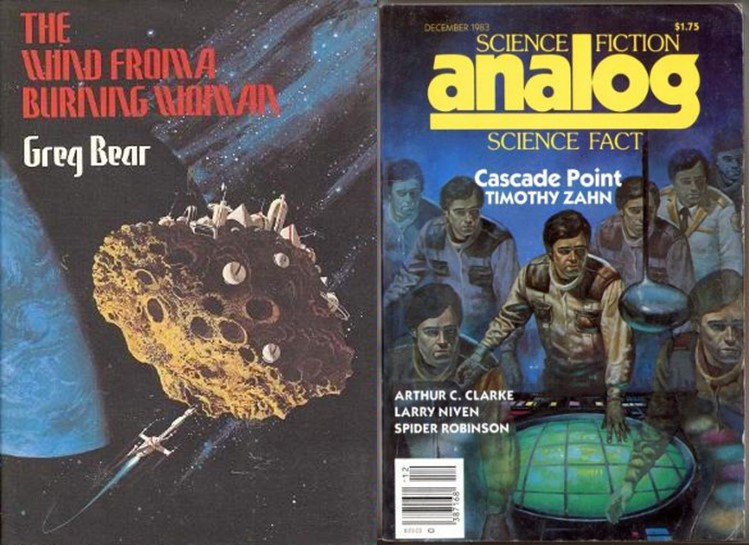

The post Women in SF&F Month: The Essential Patricia A. McKillip Cover Reveal first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Tor Doubles: #2 Greg Bear’s Hardfought and Timothy Zahn’s Cascade Point

Hardfought cover by Tony Roberts

Hardfought cover by Tony RobertsCascade Point cover by Tim White

This Tor Double has the distinction of containing two stories which were both nominated for the Hugo for Best Novella in 1984. Zahn beat out Bear for the rocket, as well as works by Hilbert Schenk, Joseph H. Delaney, and David R. Palmer. Bear wouldn’t go away empty-handed, however, since his story “Blood Music” won the Hugo for Best Novelette that same year (beating out works by Kim Stanley Robinson, George R.R. Martin, Connie Willis, and Ian Watson). Published in November of 1988, the cover for Hardfought was painted by Tony Roberts. The cover for Cascade Point was painted by Tim White.

Cascade Point was originally published in Analog in December, 1983. It won the Hugo Award for Best Novella. The story placed second in the Locus poll and the Analog Readers Poll.

Pall Durrikan is the captain on a interstellar cargo ship. Although he and his crew mostly moves cargo between planets, they also take on passengers to help cover costs and turn a profit. In order to make the trip between distant stars, they must navigate through “cascade points,” essentially jumps in hyperspace. Because of the psychological issues the occur…seeing a cascade of images of yourself that appear real…anyone who isn’t required to be awake during the jump is given sedatives to keep them asleep. On more upscale spaceships, an autopilot is installed, but the Aura Dancer, Durrikan’s ship, doesn’t have one of those, so Durrikan, or one of his crew, must stay awake during the jumps.

Early in the novella, Zahn explains that there are eight passengers on the Aura Dancer, but he only really introduces two of them, Rik Bradley and Dr. Hammerfield Lanton. Lanton is a psychiatrist who is treating Bradley for mental illness bordering wit dissociative personality issues. Since Lanton and Bradley are the only passengers introduced, it is clear that they will become important later in the story. Zahn’s decision not to introduce the other characters indicates that the human factor will be less important to the story than the technical issues that will be faced.

Despite this, and Zahn’s focus in on the narrator-Captain, he makes it clear that there is more going on the ship that the Captain sees. Alana is building a relationship with Bradley, although it mostly occurs outside the main narrator, the Captain sharing it with the reader through his perceptions of Alana. Similarly, although Lanton describes his treatment of Bradley during the Cascade Points, the reader never experiences that treatment directly. The other passengers, and most of the crew, are even less germane to the story and barely register.

Cascade Point is a puzzle story. Zahn has set up the rules for his universe and then tweaks them to make things go awry. He hints at the puzzle early in the story with references to ships that have gone missing during their jumps between stars. When the crew of the Aura Dancer finds themselves in a strange place, the puzzle begins to offer a solution. For the reader, the issue is that Zahn has created the situation and holds all the cards. He can make changes to the rules under the guise that the characters have an incomplete understanding of the way their universe works. Cascade points are used, but not entirely understood. Ming metal is known to impact the passage through cascade points, but only in an imperfect way.

The story does include several interesting ideas, including Lanton’s attempt to use the cascade points, which some believe to show images of the individual in alternative timelines, to treat Bradley’s neurosis, although Durrikan questions the concept and isn’t particularly happy about the idea of Bradley and Lanton remaining awake throughout the jumps. Unfortunately, told from Durrikan’s point of view, Zahn is limited in how far he can follow up any of those subplots, focusing only on how they impact the Aura Dancer and the fate of the passengers and crew overall. While the mysteries that crop up about the cascade points are interesting, it feels like there is a lot more happening that the reader isn’t privy to.

The Wind from a Burning Woman cover by Vincent di Fate

The Wind from a Burning Woman cover by Vincent di FateAnalog cover by Doug Beekman

Hardfought was originally published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in February, 1983. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and Nebula Award, winning the latter. It placed fifth in the Locus poll and second in the Science Fiction Chronicle Readers Poll.

John W. Campbell, Jr. was quoted as asking his writers to “Write me a creature that thinks as well as a man or better than a man, but not like a man.” In Hardfought, Greg Bear not only responds to Campbell’s challenge with the creation of the Senexi, an ancient star-faring race, but also with the creation of humans, who bear little resemblance to our own race. Layering these two creations under a lexicon which Bear does not offer to define, but the reader must learn from context, Hardfought provides a hard science fiction story which rewards the careful reader and is likely to leave the casual reader perplexed.

Bear flips back and forth between two protagonists in the story, the Senexi Aryz and a human Prufrax, although it isn’t entirely clear she is human except that Bear has applied that name to her. Her way of thinking and acting certainly feels as alien as anything Bear describes for Aryz. It is clear that the two cultures are at war with each other, but the details of the war, as well as Aryz and Prufrax’s roles in the battle are esoteric.

As with much science fiction, the patient reader is rewarded. It becomes clear that part of the reason for the war is that although the two races are different enough that they should be fighting over the same pieces of real estate, one of the issues is that they come from very different periods in the universe’s evolution. The Senexi are an ancient race, dating to practically moments after the creation of the universe. The Humans are a later race, evolving billions of years after the Senexi. The battle between the two sides is (partly) a generational issue. But even that is too simple an explanation for what is happening between the races.

In addition to the reasons for the war, Bear explores the psychology of the two races. The Senexi have a sort of brood mind with the soldiers like Aryz filling the role of a “branch ind,” clearly based on, but not entirely analogous to the society of bees on earth. The branch inds view themselves as completely expendable, but at the same time they take pride in their roles and seek to serve the brood as successfully as possible.

The humans, as seen by Prufrax, are not the individuals that we usually associate with humans and she seems to be almost a construct who is regenerated to fight as needed, her memories flashing back throughout the story. It is only slowly that her true situation comes to light and causes the reader to reëvaluate the entire story.

Bear is known as a writer of hard science fiction, and Hardfought certainly falls into that category, but it is also reminiscent of the sort of mind-bending concepts that can be found in the works of Samuel R. Delany or Gene Wolfe. Like those authors, and more than other works by Bear, Hardfought is a story which takes on deeper meaning the more time the reader gives to it, both in the reading and in the thinking about it.

While Bear (and other hard science fiction authors) often invents new science to allow himself to explore the worlds he has created, in Hardfought, Bear creates new civilizations and vocabulary, and trusts the reader to be able to figure everything out from context rather than attempting to explain what he is doing and what is happening.

The two hard science fiction stories in this volume of the Tor Doubles series both come from the same tradition, but they arrive in very different places. Zahn’s story is more traditional, and offers the reader its own twists and turns, while Bear’s tale is a much more complex and challenging exploration of the ethics of warfare and civilization.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Book Review: Senseless by Ronald Malfi

I received a review copy from the publisher. This does not affect the contents of my review and all opinions are my own.

Mogsy’s Rating: 3.5 of 5 stars

Genre: Horror, Thriller

Series: Stand Alone

Publisher: Titan Books (April 15, 2025)

Length: 432 pages

Author Information: Website

Ronald Malfi is currently one of my favorite authors and I’ve greatly enjoyed all of his recent releases. However, Senseless was a bit of a mixed bag. While it delivers many of the things I’ve come to expect from Malfi, like an eerie atmosphere with just the hint of the supernatural, this particular story just didn’t resonate with me quite as strongly.

The novel opens with the grisly discovery of a woman’s mutilated body in the Mojave Desert, not far from the outskirts of Los Angeles. Detective Bill Renney is called to the scene to examine the remains and is unsettled to find eerie similarities to the case of another murdered woman that he’d worked on a year before. In fact, there’s enough to suspect that both women might have been killed by the same person—except that unbeknownst to anyone, Renney actually has secret information about these cases that might complicate his investigation.

Meanwhile, in a glitzier part of the city, author Maureen Park is celebrating her whirlwind engagement to powerful Hollywood producer Greg Dawson when the party is crashed by his son Landon. The twenty-something young man has lived a troubled life of aimlessness and addiction, but Greg’s latest attempt to keep his son out of the spotlight by sending him to school in Europe appears to have failed yet again. Already uncomfortable with Landon’s unpredictable behavior, Maureen is even more shocked and fearful after finding some disturbing items among his belongings.

And finally, we have a third POV character, Toby. The most mysterious of all, Toby drifts from place to place, fancying himself a “human fly” escaping from the “spider” and her web at home. Then one night at a club, he encounters an enigmatic woman who claims to be a vampire, sending him spiraling further into delusion as a powerful obsession for her takes over.

Senseless is the fifth book I’ve read by the author. By now I’ve come to associate his name with atmospheric horror and emotionally driven narratives, usually led by complex and flawed characters. This book largely delivers on all these counts. On the surface, it reads like a murder mystery and almost like a police procedural, especially when we are following Renney. He was my favorite character in the book, if nothing else for his part in the plot, which felt the most grounded and compelling, giving off that gritty, noir-like quality I appreciated. In a way, his chapters were also a deep character study of the man over the course of a year, starting from the unsolved murder of the first woman, when Renney was still mourning the recent death of his wife. With the discovery of the second murder victim a year later, his guilt and grief come roaring back, joining his growing suspicions to unravel what little peace he’s managed to hold onto.

In contrast, I was not so keen on Maureen or Toby’s chapters. To be sure, this book wasn’t without its hiccups, but admittedly it could have had something to do with my own struggles with abstract themes. At times, Toby’s POV even veered into surreal territory, a truly unreliable narrator if I’ve ever seen one. Worse, his rambling, fever dream-like chapters were often to the detriment of the story’s momentum, and every time I got one of his chapters, I had the urge to skim. Maureen’s storyline fared a little better, but I found that, while initially promising, her chapters tended to get lost in the shuffle. Granted, that’s also probably because the connections between the three characters were tenuous for most of the novel and demand a fair bit of patience from the reader. While answers do eventually come in time, I wonder if perhaps Malfi may have overreached a bit in making this one so structurally ambitious.

But my one real gripe lies with the ending. The final moments felt too abrupt, too unsatisfying. Sure, I can appreciate a story that leaves room for interpretation, but the resolution to Senseless, if you can even call it that, felt too ambiguous in leaving too many questions unanswered. Is it a dealbreaker? No. But I just wish we’d gotten a little more clarity.

At the end of the day, there’s a lot to admire here, and the greatest strength of Senseless lies in how Ronald Malfi managed to tie the threads of three disparate narratives together. However, this was not one of my favorites of his books. There were moments of brilliance, where his talent for crafting striking imagery and rendering realistically imperfect human characters really shines, but when we zoom out to look at the bigger picture, the hits don’t always land as cleanly as they aim for. As a fan of Malfi’s work, I’m still glad I read this, but for newcomers, there are probably more solid choices for an introduction to his horror and thriller fiction, like Come With Me or Black Mouth.

![]()

![]()

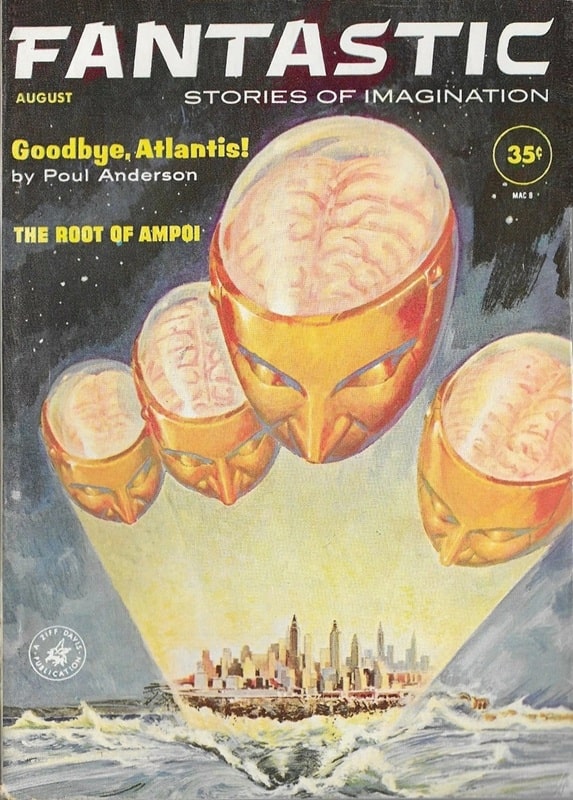

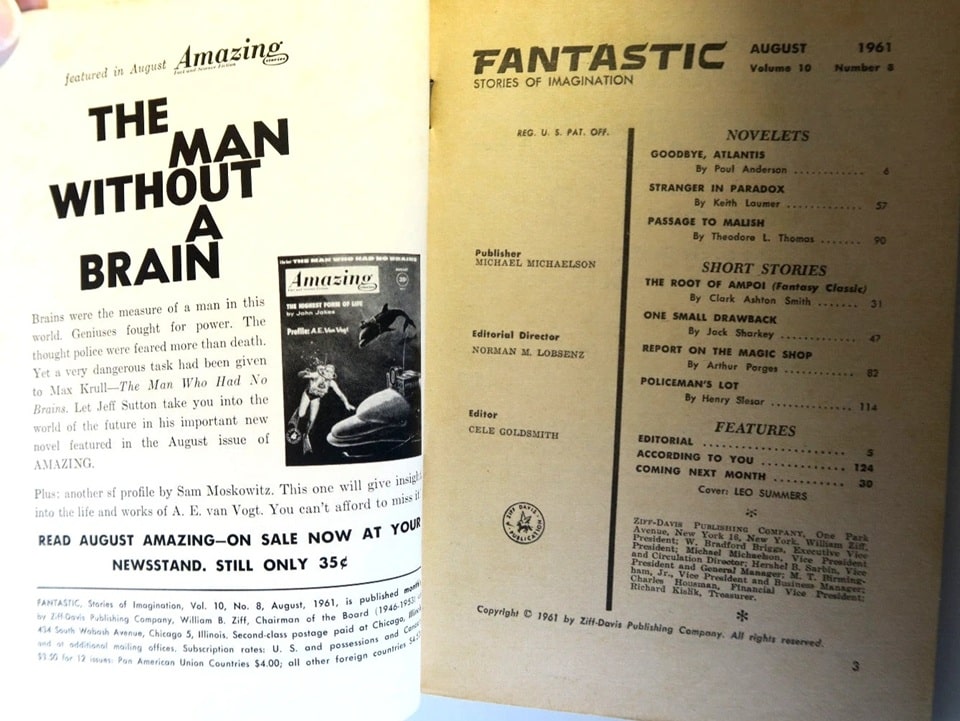

Fantastic, August 1961: A Retro-Review

Fantastic, August 1961. Cover by Leo Summers

It’s been a long time since I did a Retro-Review from Cele Goldsmith’s time at Amazing/Fantastic. So I’m happy to be back at it! This issue is from about two years into Goldsmith’s tenure.

There are two features — Norman Lobsenz’s editorial, and the letter column, According to You. (Well, and a brief Coming Soon piece.) The editorial talks about using computers to analyze the various items certain Thais believe have magical powers, ending with a slight joke about hoping to find a love philtre “for Cele.” It introduces the concept by talking about the famous Arthur C. Clarke story in which a computer helps Tibetan monks list all the names of god — but misidentifies the story weirdly by adding another billion names: “The Ten Billion Names of God.”

[Click the images for fantastic versions.]

Table of Contents for Fantastic, August 1961

Table of Contents for Fantastic, August 1961

According to You has six letters. I recognized some well-known fans: Bill Bowers and Redd Boggs were both prolific fanzine editors and multiple Hugo nominees. Lawrence Crilly, John Pocsik, and David Charles Paskow are not as was well known but do get mentions in Fancyclopedia 3, and indeed the Paskow Collection at Temple University is named for David Paskow. F. C. MacKnight is the other contributor.

The letters concern mostly Fritz Leiber and the newly instituted use of one reprint per issue — both get praise. David Bunch is of course mentioned — negatively by Bowers and positively by Paskow (the latter mention getting this relieved comment from Goldsmith: “We figured that if we kept publishing [Bunch], somebody sooner or later would agree with us that he has something in his stories.”)

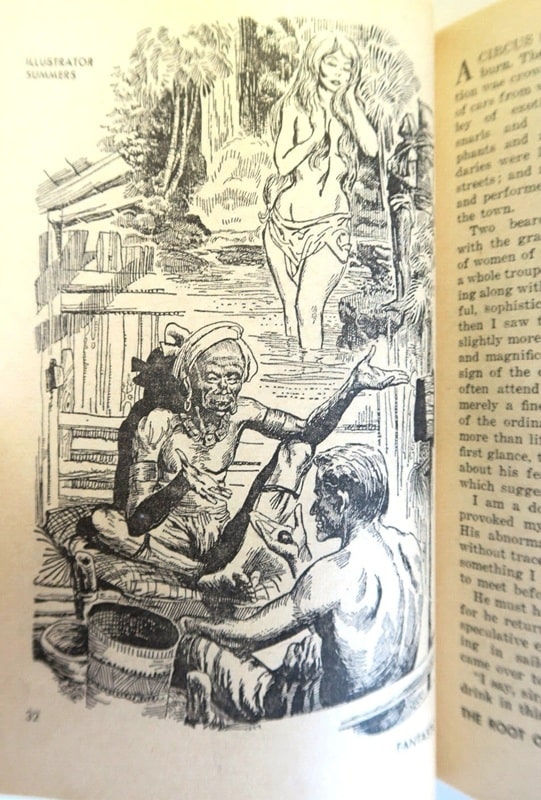

The cover is by Leo Summers, the interiors are by Summers, Virgil Finlay, West, Dan Adkins, and Larry Ivie, with a Summers back cover based on the Smith story, and one cartoon by Frosty.

The stories, then.

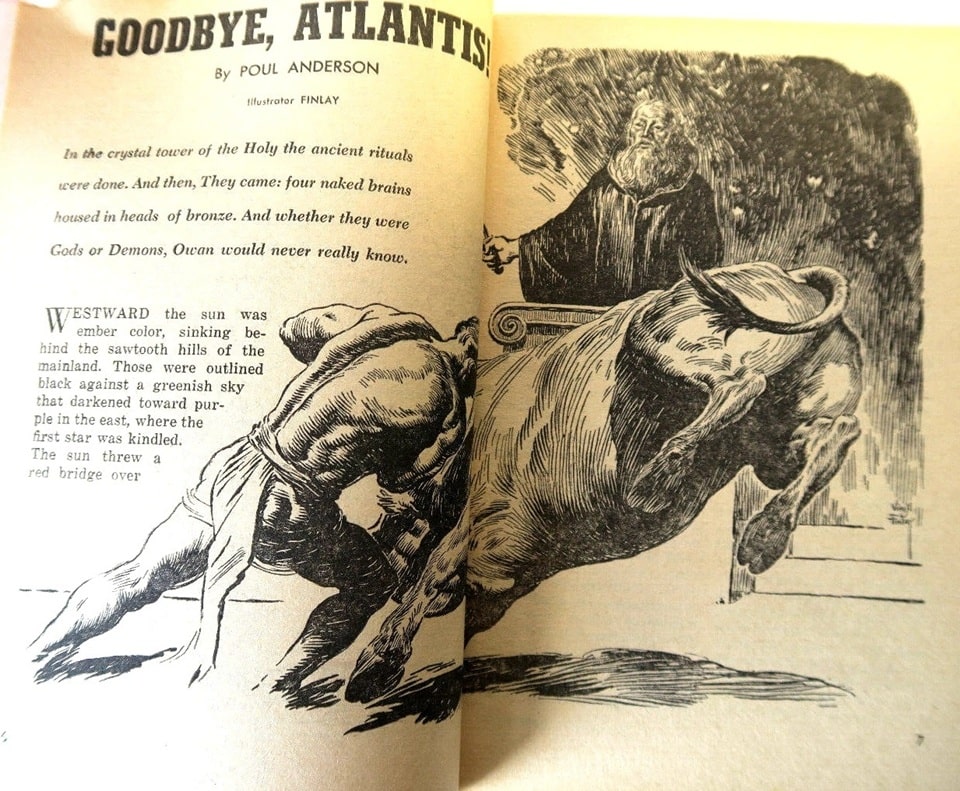

Novelets“Goodbye, Atlantis!,” by Poul Anderson (9,000 words)

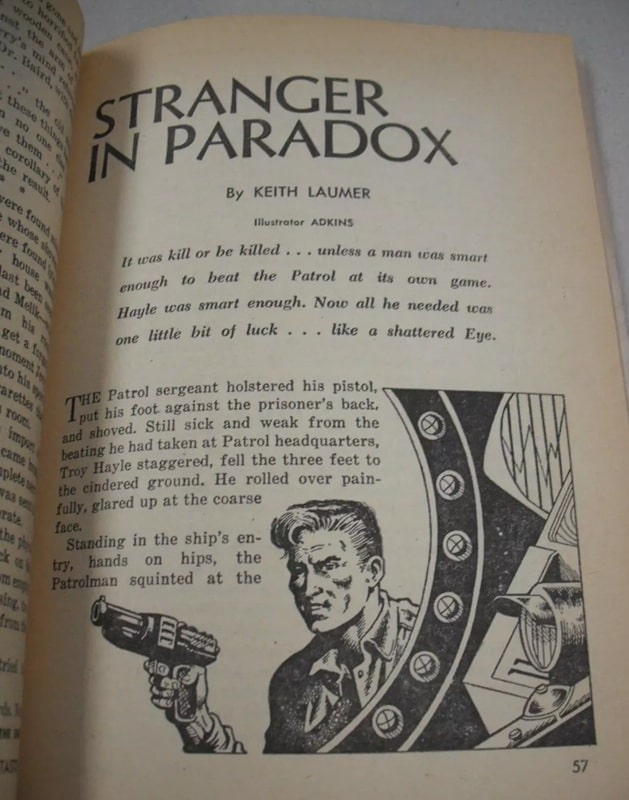

“Stranger in Paradox,” by Keith Laumer (9,200 words)

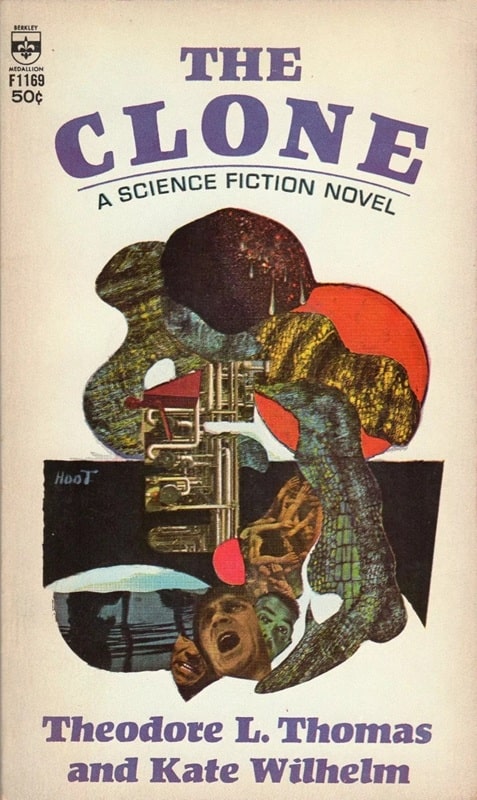

“Passage to Malish,” by Theodore L. Thomas (9,000 words)

“The Root of Ampoi,” by Clark Ashton Smith (5,900 words)

“One Small Drawback,” by Jack Sharkey (3,800 words)

“Report on the Magic Shop,” by Arthur Porges (3,000 words)

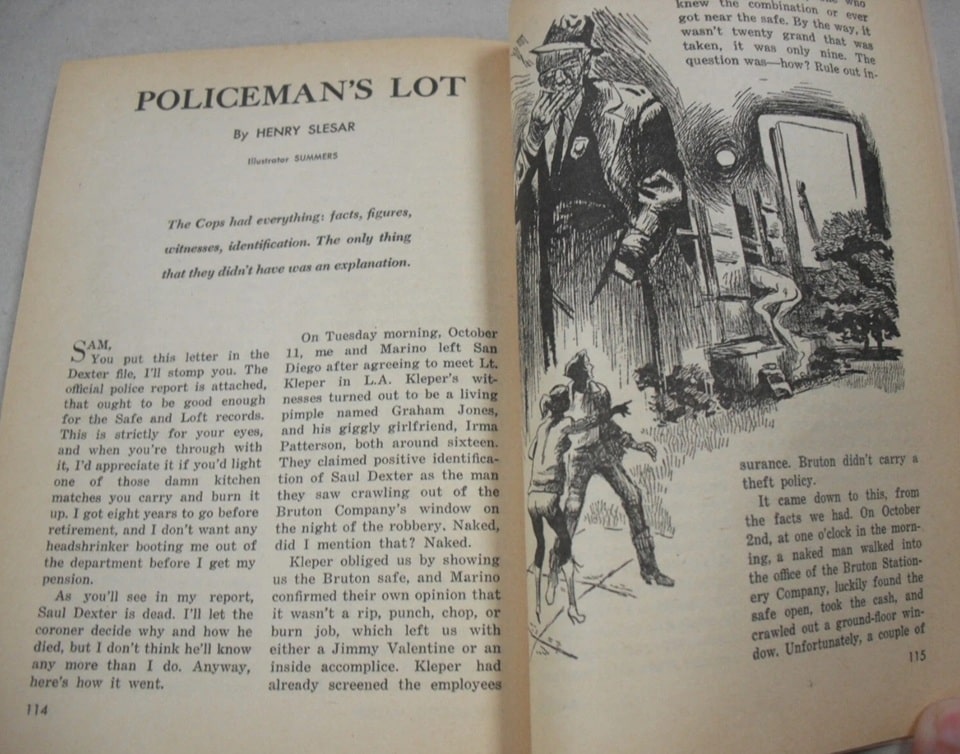

“Policeman’s Lot,” by Henry Slesar (3,600 words)

“Goodbye, Atlantis!” by Poul Anderson, illustrated by Virgil Finlay

“Goodbye, Atlantis!” by Poul Anderson, illustrated by Virgil Finlay

“Goodbye, Atlantis!” is a very obscure Anderson story — it’s only ever been reprinted once, in one of Sol Cohen’s super cheap and ugly all-reprint magazines, which mostly or entirely mined the Amazing/Fantastic backlist for material (and reprinted it (legally) without pay until SFWA objected, after which apparently Cohen made nominal payments.)

The lack of reprints is a bit odd, because “Goodbye, Atlantis!” isn’t terrible. It’s no lost classic, but it’s fine. The viewpoint character is Owan, a guard Captain in the retinue of the nobleman Donwirel and his wife Rianna, who is the niece of the former king of Atlantis, and thus cousin to the current king. Owan is in love with the beautiful Rianna, but at this time the concern is that there is a rebellion against the new king.

‘Goodbye, Atlantis!” Illustration by Finlay

‘Goodbye, Atlantis!” Illustration by Finlay

The plot turns on the efforts of the Archpriest Govandon to summon the long absent gods of Atlantis to vanquish the rebels, who are clearly winning the war and have the capitol under siege. Owan has concerns — he doesn’t trust the gods, or perhaps simply doesn’t trust that Govandon’s spells will work. He goes to attend Donwirel, who is working with Govandon — and is poisoned.

It’s clear that Donwirel is a traitor, and only Rianna’s timely intervention saves Owan, after which he struggles to prevent Donwirel from stealing the spells Govandon has learned. There’s some solid action, and Owan (and Rianna) are successful — but their success proves profoundly ambiguous. (Behind it all is a sly suggestion that the rebels were right all along.)

“Stranger in Paradox” by Keith Laumer. Illustrated by Dan Adkins

“Stranger in Paradox” by Keith Laumer. Illustrated by Dan Adkins

“Stranger in Paradox” was, I think, Keith Laumer’s fourth published story. The first two, “Greylorn” and “Diplomat-at-Arms” were published by Goldsmith as well — Laumer was one of her major discoveries, along with Le Guin, Disch, Zelazny and to some extent Ballard (for the American market.) The Retief stories (after “Diplomat-at-Arms”) ended up finding a home in Frederik Pohl’s If, but Goldsmith otherwise published a great deal of Laumer’s early work.

Alas, “Stranger in Paradox” is pretty awful. Hayle is dumped on the title planet by the Patrol, who seem to be the agents of the despotic rulers of this future. (Details are pretty slight.) They leave him nothing but a short sword and a reusable match. The only rule on Paradox is that prisoners cannot cooperate — they must either avoid each other or fight.

Hayle’s plan is to somehow convince a couple of other people to cooperate, and after figuring out how the Patrol keeps track of the prisoners, he manages that … and then, with a profoundly implausible plot, lots of luck, a woman prisoner falling into their laps, and utterly ridiculous concept of both how the Patrol would work and how they control civilization, they succeed. It’s just dumb dumb dumb the whole way, redeemed only slightly by the fight scenes that are, as usual, quite good — Laumer had the knack of writing fights.

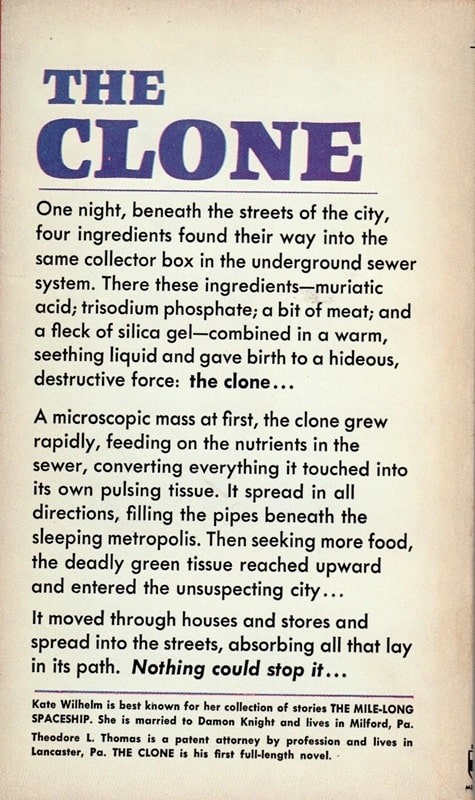

The Clone by Theodore L. Thomas and Kate Wilhelm

(Berkley Medallion, December 1965). Cover by Hoot von Zitzewitz

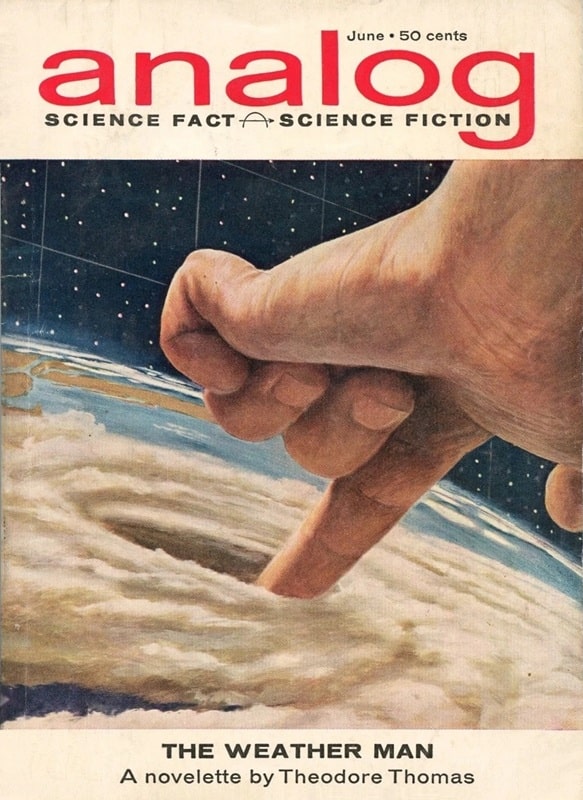

Theodore L. Thomas (1920-2005) was a chemical engineer and patent attorney who wrote about 50 short stories between 1952 and 1981. He wrote two novels in collaboration with Kate Wilhelm (The Clone and The Year of the Cloud.) He is probably best known still for a series of stories he wrote as “Leonard Lockhard” about science fictional complications with patents — the first two of these in collaboration with fellow patent attorney Charles Harness; and for his story “The Weather Man,” about human control of the weather.

Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction June 1962, containing “The Weather Man” by Theodore L. Thomas. Cover by John Schoenherr

Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction June 1962, containing “The Weather Man” by Theodore L. Thomas. Cover by John Schoenherr

“Passage to Malish” is about a salesman who finds himself diverted from his trip to the planet Malish because it’s been determined that he’s the perfect person to confront the visiting aliens from the Large Magellanic Cloud. The solution involves turning him into a superhuman, committing genocide (or galactocide, I suppose), and then hoping he’ll consent to being turned back to a normal human before he uses his powers to subvert the Milky Way. I never believed any of this story for a second.

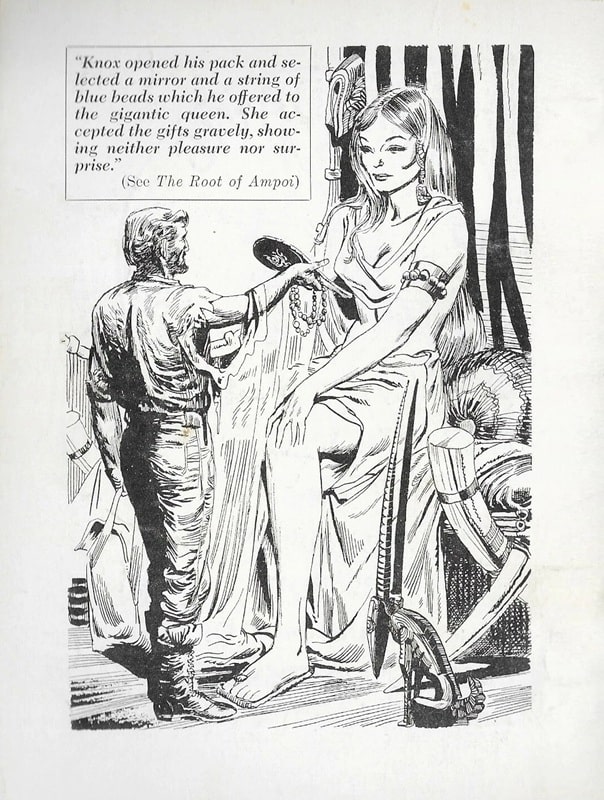

“The Root of Ampoi” by Clark Ashton Smith. Illustration by Summers

“The Root of Ampoi” is Sam Moskowitz’s choice for this month’s fantasy reprint. Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961) was a poet and a writer of weird fiction whose reputation has gone up and down over time, and seems on the upside now. He was a regular contributor to Weird Tales, and part of Lovecraft’s circle. He was known for his ornate prose and extravagant imagination, so, Moskowitz, with his impeccable as ever taste, declaring in more or less Salieri mode that Smith used “too many words” (that’s my paraphrase of Moskowitz’ words) chose a completely uncharacteristic story to reprint. (That said, it has been reprinted fairly often, one time as “The Ampoi Giant,” so other people may disagree with me.)

“The Root of Ampoi” is a tale told by a giant working for a circus. He was a sailor, and he heard of a place on New Guinea where the men were normal sized and the women were nine feet tall. And there were rubies to be had for a song. Seeking to make his fortune, he finds this place, and learns about the secret that makes the women so tall — after the queen of those women chose him for a consort. But, unhappy with being dominated by a much larger wife, he ferrets out the secret… the punishment for which is banishment. No rubies either. But — easy to find circus work. This is really minor stuff — a competently executed tall tale, really. But it seems nothing like a real introduction to CAS.

Jack Sharkey (1931-1992) was a Cele Goldsmith regular, though to my taste he was a pretty weak writer. “One Small Drawback,” however, is not too bad at its length. Jerry, a college kid, is intrigued by his professor’s research into telekinesis, but nothing he tries has any effect. His professor is convinced that what he needs is true belief. Then something small happens that convinces Jerry he can use telekinesis… but it doesn’t work consistently. The key element he eventually discovers is pretty clever, and effectively dark.

Arthur Porges (1915-2006) wrote over 200 stories, split roughly 50/50 between mystery and SF. His stories were mostly fairly short, and were consistently clever, sometimes amusing, sometimes quite mordant. As a writer of exclusively short fiction, he’s not really widely remembered, but he was one of the most dependably enjoyable writers in the field, and his contributions appeared right up until his death, mostly in F&SF but also in Goldsmith’s magazines. “Report on the Magic Shop” is good solid fun, nothing earth-shattering, written as if the author is telling the editors about the various products sold at a magic shop he happened to stumble into.

“Policeman’s Lot” by Henry Slesar. Illustration by Summers

“Policeman’s Lot” by Henry Slesar. Illustration by Summers

Henry Slesar (1927-2002) was another writer of both SF and crime fiction, with most of his SF fairly short. He was better known as a mystery writer, and so perhaps it isn’t a surprise that “Policeman’s Lot” is basically a mystery, though with a fantastical solution.

A veteran patrolman submits a report on a strange case he recently investigated, involving a couple of basically “locked room” thefts, in which in one case a man was found escaping from a window naked. Not long after, the man is found crushed to death in his house. The strange factor is that he seems to have changed height between separate arrests. The solution is kind of obvious, and acceptable except as an explanation of his death.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was We Are Missing Important Science Fiction Books. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over 200 articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Women in SF&F Month: Sara Hashem

Today’s Women in SF&F Month guest is Sara Hashem! Her Egyptian-inspired epic fantasy debut novel, The Jasad Heir, was a Sunday Times bestseller and a Goodreads Choice Award nominee in the Romantasy category. Her next novel and the conclusion to her Scorched Throne duology, The Jasad Crown, will be released on July 15. I’m very excited for its release since her first novel was one of my favorite books of 2023 with its excellent banter and character dynamics, including an […]

The post Women in SF&F Month: Sara Hashem first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Spotlight on “Measure of Devotion” by Nell Joslin

Measure of Devotion, Nell Joslin’s fantastic novel, is the sweeping grandeur of the mountains, the…

The post Spotlight on “Measure of Devotion” by Nell Joslin appeared first on LitStack.

On McPig's Wishlist - Hallowed Games

Hallowed Gamesby C.N. Crawford

Hallowed Gamesby C.N. CrawfordIf he’s death, I crave oblivion.

I'm cursed to kill with a brush of my fingertips. My worst fear is attracting the attention of the kingdom’s magic hunters. Maelor is their mysterious, gorgeous leader--and my world falls apart when he learns my secret.

When he arrests me, my only hope is to survive a deadly competition, to win the mercy of our god. Strangely, Maelor is immune to my touch. Turns out, that’s because he’s secretly a vampire—lethally sexy, and dangerous as hell.

He's as drawn to me as I am to him. Can this beautiful monster help me survive, or will our dark attraction lead me to ruin?

Women in SF&F Month: Karin Lowachee

Todya’s Women in SF&F Month guest is Karin Lowachee! Her short fiction includes “A Borrowing of Bones” (selected for the Locus Recommended Reading List), “Meridian” (a Sunburst Award finalist that was also selected for The Best Science Fiction of the Year, Volume 3), and “A Good Home” (selected for The Best Science Fiction of the Year, Volume 2). She is also the author the Philip K. Dick Award–nominated novel Warchild and the rest of the books in The Warchild Mosaic, […]

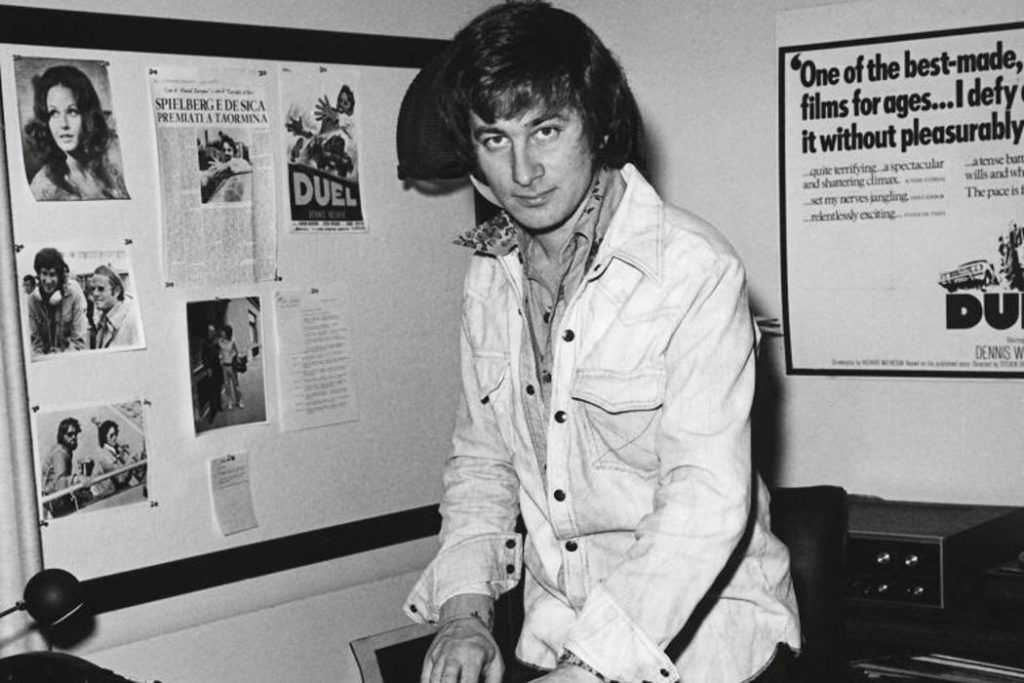

The post Women in SF&F Month: Karin Lowachee first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Movie of the Week Madness: Duel

Can anyone dispute Steven Spielberg’s title as the most successful motion picture director of all time? Not if you’re talking box office, you can’t. As of June, 2024, Spielberg’s films have grossed almost eleven billion dollars, putting him two billion ahead of his nearest competitor, James Cameron, and as Randy Newman sang, it’s money that matters. In Hollywood that’s probably truer than anywhere else in the world, and the profits generated by Spielberg’s many successes have more than made up for the losses incurred by his rare failures, making the suits very, very happy.

What about recognition from colleagues and critics? He has been nominated nine times for Best Director, winning twice (for Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan), and he received another Oscar as the producer of Schindler’s List when that film won Best Picture. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (you can step on him at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard), has won the Academy’s prestigious Irving Thalberg Award (are there any awards that aren’t prestigious?), and has received more honors from various cinematic guilds and organizations than can easily be counted.

This storied career had its humble beginning in television in 1969, when Spielberg directed an episode of Rod Serling’s Night Gallery, and through the early 70’s he directed episodes of various other television shows, including the very first episode of Columbo, Murder by the Book. (And yes, I know about Prescription Murder and Ransom for a Dead Man, but technically those are stand-alone TV movies, not episodes of the series.)

And speaking of TV movies, Spielberg also directed three segments of the ABC Movie of the Week, one of which still stands as arguably the best made-for-TV movie ever. I’m talking, of course, about Duel.

The ABC Movie of the Week ran for six seasons between 1969 and 1975, featuring original made-for-television fare from all genres, and the mere thought of the show can make many people of my age fall to the floor in a swoon, regaining consciousness with visions of Barbara Eden dancing in our heads and the scent of Kraft Mac and Cheese lingering in our nostrils. It’s only when we lift our faces from the carpet and see that it isn’t burnt-orange shag that we realize it’s not 1972.

Most of these “world premier” movies ranged from the merely forgettable (Gidget Gets Married) to the utterly schlocky (Satan’s School for Girls) to the absolutely godawful (The Feminist and the Fuzz). In other words, they were nothing to write home about, especially when seen from the distance of half a century (we had far fewer options in the 70’s, so when the trainer threw us a fish we clapped our flippers and snapped it up, fresh or not), but some MOWs were better than that, and at the pinnacle are a bare handful that still hold up, even when viewed with eyes unclouded by cataracts or nostalgia.

None of them stand higher than Duel, which was broadcast on Saturday, November 13, 1971. Directed by a twenty-four-year-old Steven Spielberg and scripted by the great Richard Matheson from his own short story, it’s the rare product of its era that can hit an unsuspecting viewer of today almost as hard as it did its original audience. (I’m sure it’s not a coincidence that Richard Matheson wrote two more of the best ABC MOWs, Trilogy of Terror and The Night Stalker.)

Duel begins in the most prosaic fashion imaginable, with salesman David Mann (Dennis Weaver) backing his red Plymouth Valiant out of his modest suburban garage and heading north for an important meeting with a client; almost all of the first five minutes of the film are through-the-windshield POV shots of the early stages of Mann’s journey. We see him motor up CA 5 through Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley; eventually traffic thins out as he enters the intermediate region where upper Southern California gradually morphs into lower Central California. Soon almost all other traffic vanishes as Mann leaves the 5 and swings north-east, continuing into the Mojave Desert on smaller, two-lane highways. (Just what he could be selling to anyone in this bleak, post-apocalyptic landscape is never addressed. Geiger counters, maybe?)

It is on an empty stretch of one of these roads that the duel begins, without Mann at first even realizing it. He comes up behind a massive, dirt-encrusted, smoke-spewing tanker truck (a 1957 Peterbilt 281, chosen by Spielberg for its menacing “face”), and not wanting to be late for his meeting, Mann passes it. The truck immediately shows its displeasure by aggressively passing Mann to regain the lead, angrily blowing its horn as it goes by. Increasingly worried about falling behind schedule, Mann repasses the tanker and puts on speed in the hopes of leaving this annoyance behind.