Fantasy Books

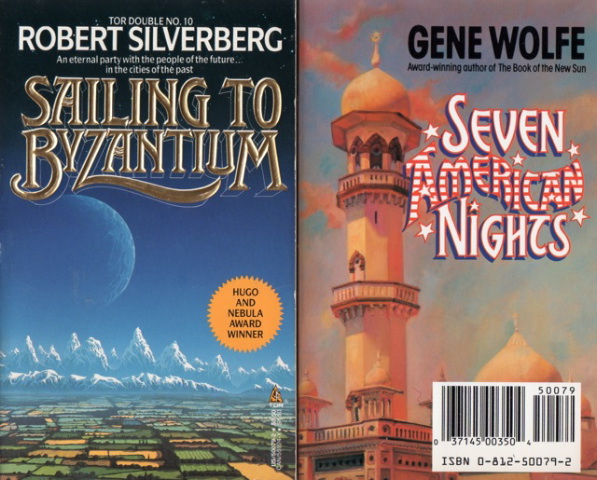

Tor Double #10: Robert Silverberg’s Sailing to Byzantium and Gene Wolfe’s Seven American Nights

Cover for Sailing to Byzantium by Brian Waugh

Cover for Sailing to Byzantium by Brian WaughCover for Seven American Nights by Bryn Barnard

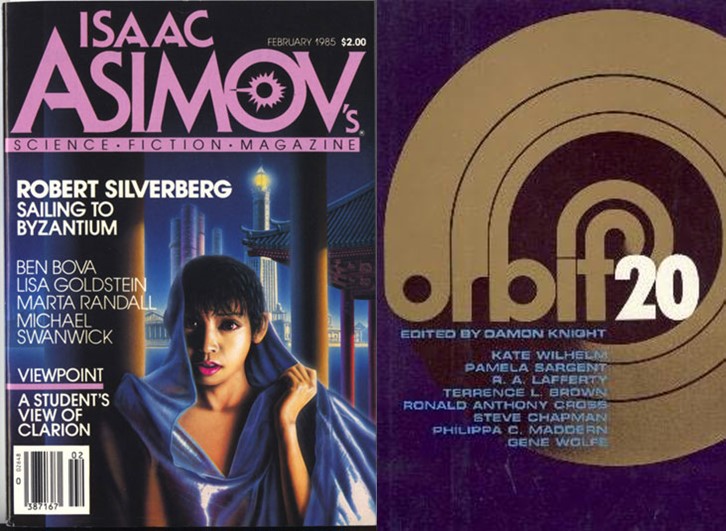

Seven American Nights was originally published in Orbit 20, edited by Damon Knight and published by Harper & Row in March, 1978. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award. Seven American Nights is the first of two Wolfe stories to be published in the Tor Doubles series.

Sailing to Byzantium was originally published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in February, 1985. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award, winning the latter. Sailing to Byzantium is the second of five Silverberg stories to be published in the Tor Doubles series and aside from the proto-series Laumer novel, it is the first time an author has been repeated.

Wolfe’s story opens with a short note from Hassan Kerbelai indicating that he is sending the travelogue of Nadan Jaffarzadeh back to his family, noting that Jaffarzadeh seems to have gone missing. The final paragraphs of the story are focused on Jaffarzadeh’s mother’s reaction to the travelogue. The majority of the story is Jaffarzadeh’s description of his first week visiting America.

The American Jaffarzadeh is visiting, however, is one in which the United States failed generations earlier. The Washington, D.C. he travels through is referred to as the Silent City, containing the remnants of the great federal buildings. Although he travels through the ruins and visits a park that he warns is dangerous, the majority of his time in Washington is spent attending the theatre.

During his first day of touring, he notices a man working in one of the buildings in the silent city. He runs into the man at the theatre and learns that he is working on a machine that can emulate handwriting, essentially what we would recognize as an AI with an autopen ability.

After that early visit to see a production of Gore Vidal’s Visit to a Small Planet, he develops an infatuation for the leading lady, Ardis Dahl. That infatuation drives the remainder of the narrative as he begins to stalk her, attending subsequent nights at the theatre, trying to find where she lives, and eventually meeting one of the other actors, Bobby O’Keene, who offers to introduce Jaffarzadeh for a price. When O’Keene tries to pick Jaffarzadeh’s pocket, the police become involved, O’Keene is arrested, and eventually, Dahl tracks down Jaffarzadeh to get his help releasing O’Keene.

The story is told in the form of Jaffarzadeh’s journal, beginning with his arrival aboard a ship and ending after he begins a relationship with Dahl. However, Wolfe introduces several subtle clues throughout the story, in his choice of plays, the descriptions of characters, and incongruities in the way Jaffarzadeh describes things, that indicate that the seemingly straightforward tale is much more convoluted that it would appear.

Upon reading the story, it appears that Jaffarzadeh is somehow the victim of a scam perpetrated by the acting troupe, possibly in conjunction with the manager of the hotel who first sent him to the theatre. However, Wolfe’s choice of plays, one that deals with a traveler attempting to provide a war, the other about a woman who vanishes, indicate that something far more sinister is taking place. Two of Jaffarzadeh’s fellow passengers to America make appearances late in the story. Are they part of the plot? Are the police involved? What about the functionary who sent the journal on to Jaffarzadeh’s family? Wolfe doesn’t offer any real answers and the text, itself, can offer up a Rashomon-like series of answers, none of them more correct than the others.

Seven American Nights feels incomplete. Not only does Wolfe not provide answers to the many questions that are implied, but rarely stated, but he ends the story with Jaffarzadeh’s mother’s not knowing his fate, but knowing he is alive. The reader, on the other hand, is not so sure. Even if Jaffarzadeh can be trusted, and by his own words he notes that he hasn’t included the entire story and has removed pages, the possibility that someone else, possibly even the machine his friend was working with, wrote parts of the journal mean it cannot be trusted.

The described arrest of O’Keene after he tried to pickpocket Jaffarzadeh, in which it is clear that if Jaffarzadeh doesn’t swear out a complaint, the police will arrest him anyway and trump up the charges, coupled with the inability to discover where he is being kept or what happened to him, has chilling parallels with the current situation in which ICE is arresting people and deporting them without due process. Within the context of the story, it also sets the expectation that if the authorities determine that Jaffarzadeh must be removed, there is nothing that anyone could do to stop them or reverse his arrest.

The strength of Seven American Nights is the very infuriating ambiguity with which Wolfe has carefully laced the story.

Issac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine February 1985 cover by Hisaki Yasuda

Issac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine February 1985 cover by Hisaki YasudaOrbit 20 cover by an unknown artist

The strength of Seven American Nights is the very infuriating ambiguity with which Wolfe has carefully laced the story.

Silverberg’s world of Sailing to Byzantium is reminiscent of the fin du siècle decadence of Michael Moorcock’s Dancers at the End of Time, which I recently re-read. While Moorcock viewed the world of ever-changing landscape from the point of view of one of the period’s denizens (or citizens as Silverberg calls them), Silverberg’s protagonist, is in the time traveling role of Moorcock’s Mrs. Amelia Underwood. This change makes Silverberg’s world more interesting since it allows the story to offer its own contemporary judgement of the citizens’ self-indulgence.

Of course, Silverberg’s story shares its title with a poem by William Butler Yeats in which Yeats also explores the concepts of immortality, art, and the idea of a paradise. Silverberg has selected as his point of view Charles Phillips, who, without knowing how or why, has been pulled from twentieth century New York to this new world. Phillips moves from city to city accepting of the immortality which seems to exist for the citizens and trying to find his own place among the glories or the past recreations.

When the story opens, he is visiting Alexandria at its height, exploring the Pharos and the library in the company of his lover, Gioia. During this visit, Phillips shares with the reader what he knows of this world. The population of citizens numbers in the low millions. Only five cities exist at any time and they are recreations of historic cities, at the moment the novella begins they include New Chicago, Alexandria, Changan, Asgard, and Timbuctoo. Eventually one of those cities will be dismantled and replaced with another city. These citizen are staffed by “temporaries,” sort of synthetic humans or automatons, Phillips isn’t entire sure.

Even as he enjoys the climb to the top of Pharos, he yearns for a Byzantium which hasn’t been built, but which he is sure will be in time. Before it can be, he and Gioia travel to Changan to enjoy the court of the Chinese Emperor. Their visit there is made more memorable by the fact that Gioia’s friends have arranged from them to be treated as honored guests by the Emperor. During their visit, Phillips begins to see the world beyond the façade. When the Emperor, who is merely a temporary, is not actively engaging, he practically seems to turn off.

The real surprise comes we he sees signs of aging in Gioia, something that shouldn’t happen to the immortal citizens of this era. Gioia leaves him, but arranges for him to have a friend, Belilala, as a companion. Unable to understand what is happening, Phillips chases after Gioia, learning from Belilala that Gioia is a rarity, a citizen who can age and die. Phillips chases after Gioia, despite her stated desire not to see him, reminiscent of Silverberg’s own Born with the Dead, which was the first of Silverberg’s novels to be reprinted in the Tor Double series.

Phillips quest of Gioia introduces him to two other visitors such as himself. The first, Francis Willoughby, is from the late sixteenth century and can’t fathom of the world of miracles Phillips attempts to describe them living in. He is convinced he was simply drugged and dragged to an India ruled by Portuguese (they meet in a recreation of Mohenjo-daro, which replaced Timbuctoo). The second visitor Phillips meets is from a period in his future. Y’ang-Yeovil of the Third Septentriad. Y’ang-Yeovil reveals more about the mechanics of the world, and the manner in which visitors are brought into it, causing Phillips to have an identity crisis of his own.

Eventually, Phillips is able to confront Gioia about her desertion of him and her own aging. While Phillips may be a minority as a visitor, Gioia is a very different type of outsider. A citizen, her recessive trait that causes her to age means that she is still seen as an outsider with little recourse or others who share her affliction. Phillips actually quotes the Yeats poem and Byzantium becomes a promised land where a solution to her affliction might become a possibility, allowing Gioia and Phillips to have a life together without worry of out-aging the other.

The world Silverberg built is a strangely ephemeral world in which the only permanence are its citizens. He focuses on two individuals who lack the immortality that almost everyone else in the world enjoys, and each of them must figure out how to come to terms with that fact in their own way, both coming from very different places. Although it doesn’t seem likely, their story introduces true affection into the world.

Some of the novellas collected in any given volume of Tor Double have links to each other. In the case of this book, both the Wolfe and Silverberg novellas are travelogues of a future earth, with Wolfe exploring the remnants of a post-US Washington and Silverberg looks at a future world that recreates the past.

The cover for Sailing to Byzantium was painted by Brian Waugh. The cover for Seven American Nights was painted by Bryn Barnard.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

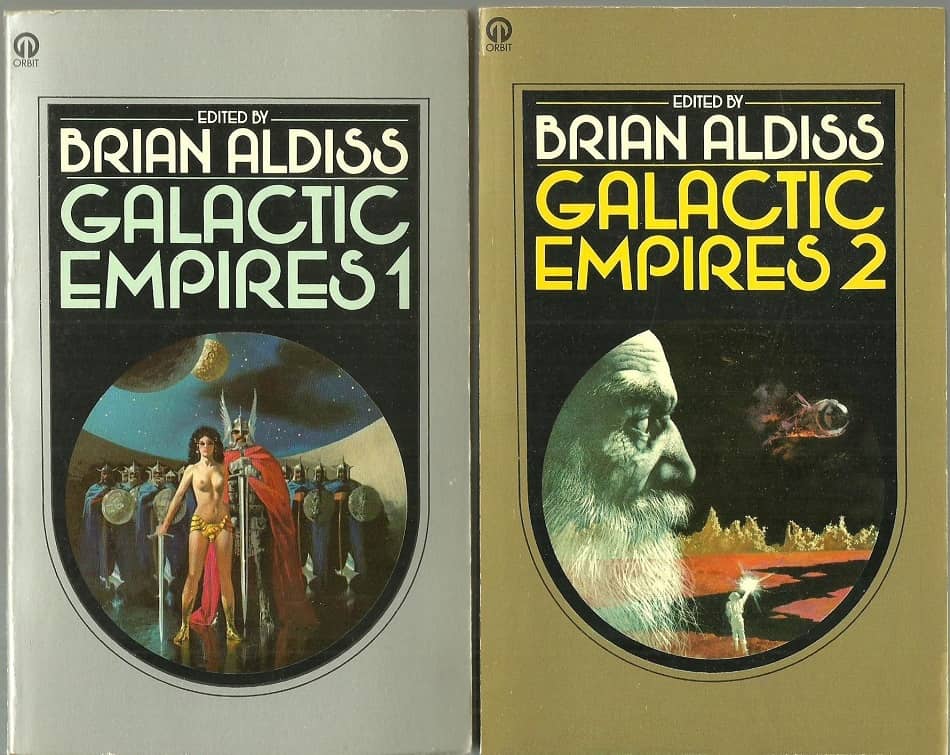

Vintage Empires: James Nicoll on Galactic Empires, Volumes One & Two, edited by Brian W. Aldiss

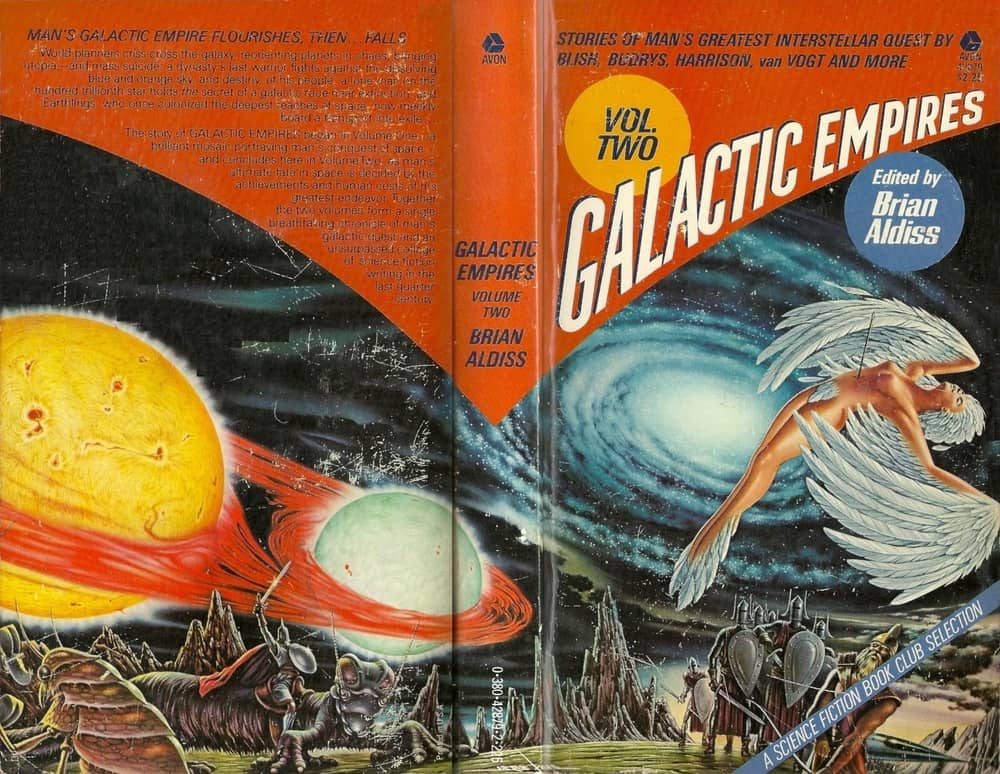

Galactic Empires, Volume One and Two (Orbit, October 1976). Covers by Karel Thole

Galactic Empires, Volume One and Two (Orbit, October 1976). Covers by Karel Thole

My fellow Canadian James Nicoll continues to be one of my favorite SF bloggers, probably because he covers stuff I’m keenly interested in. Meaning exciting new authors, mixed with a reliable diet of vintage classics.

In the last two weeks he’s discussed Kate Elliots’s The Witch Roads, Axie Oh’s The Floating World, Ada Palmer’s Inventing the Renaissance, and Emily Yu-Xuan Qin’s Aunt Tigress, all from 2025; as well as Walter Jon Williams The Crown Jewels (from 1987), Wilson Tucker’s The Long Loud Silence (1952), C J Cherryh’s Port Eternity (1982), and John Brunner’s 1973 collection From This Day Forward. Now that’s a guy who knows how to productively use his leisure time. Not to mention caffeine.

But my favorite of his recent reviews is his story-by-story breakdown of Brian W. Aldiss’s massive two-volume anthology Galactic Empires, which made me want to read the whole thing all over again.

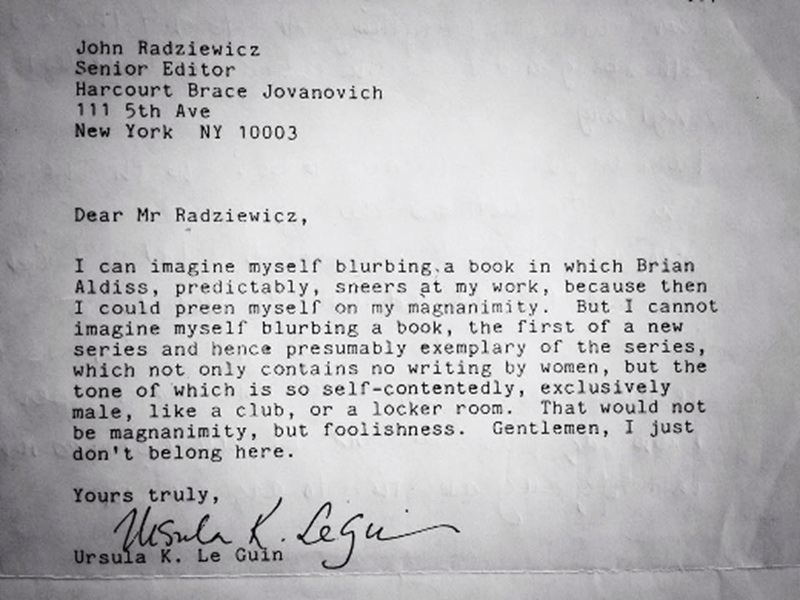

James opens by reprinting the famous letter Ursula K. Le Guin sent to Harcourt senior editor John Radziewicz, when she was asked to provide a blurb for Volume 1 of George Zebrowski’s new anthology series Synergy: New Science Fiction. It didn’t go well.

Ursula Le Guin letter to Harcourt senior editor John Radziewicz

Ursula Le Guin letter to Harcourt senior editor John Radziewicz

As James notes,

Modern readers might be surprised at the almost complete lack of women in the two volumes (or they would be, if the books were not long out of print). Older readers, aware of Le Guin’s response to a later Aldiss-helmed anthology, will be less surprised.

On to the stories.

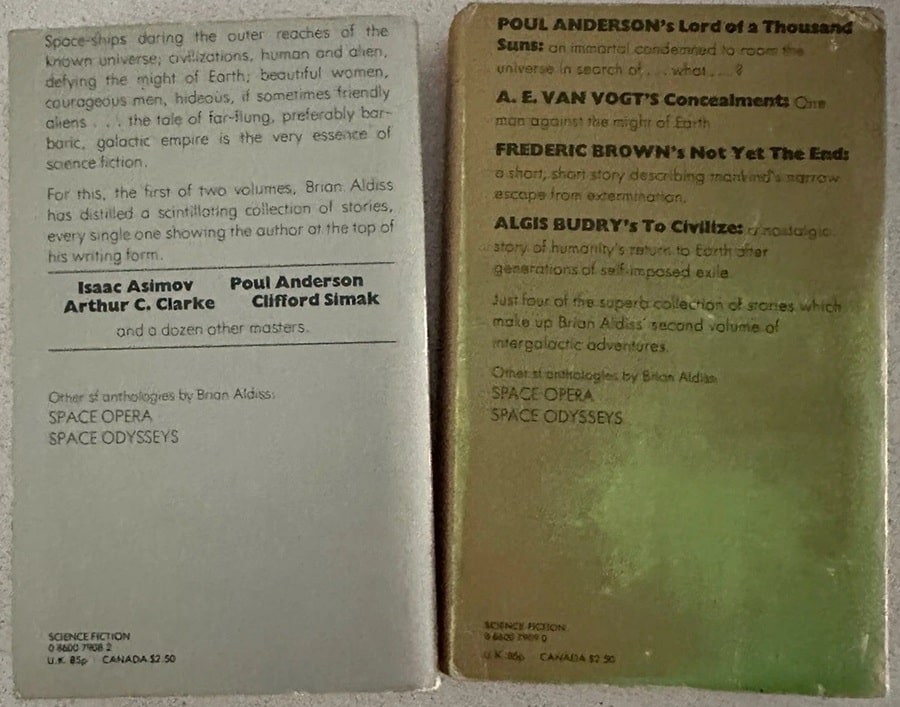

Back covers to the Orbit paperback editions of Galactic Empires, Volume One and Two

Back covers to the Orbit paperback editions of Galactic Empires, Volume One and Two

James covers every one of the stories in this massive anthology. Here’s the highlights.

VOLUME ONEI remembered Volume Two as the stronger of the two. That’s not quite correct. Both have their weak stories (“Foundation,” in the absence of other material, “Escape to Chaos,” not to mention that terrible van Vogt story) but both have works such as “Brightness Falls from the Sky” and “Final Encounter” that I enjoyed encountering again…

“The Star Plunderer” • (1952) • novelette by Poul Anderson — a Technic History story

Alien slavers descent on decadent, weak Earth, little suspecting that their actions will provoke the rise of the TERRAN EMPIRE! The guy does not get the girl. There are enough Anderson Guy Doesn’t Get the Girl stories for an anthology. I wonder why?

“Foundation” (1942) • novelette by Isaac Asimov — a Foundation tale

Endangered due to the slow collapse of the Empire, the Encyclopedists on distant Terminus discover the true reason that their science colony was founded. Without the context of the other Foundation stories, this one seems oddly anti-climactic. Yet it seems to have been wildly popular back when.

“Resident Physician” (1961) • novelette by James White — a Sector General story

What led a terribly ill immortal alien to turn on its physician? And can the staff of Sector General solve the mystery, given they’ve never previously encountered this species? One has to admire how calmly the staff of Sector General take being presented with what amounts to a demigod, especially an angry, apparently homicidal demigod. One of the principal characters in Sector General stories is psychology section-head Major O’Mara, described thusly:

“(O’Mara) was also, on his own admission, the most approachable man in the hospital. O’Mara was fond of saying that he didn’t care who approached him or when, but if they hadn’t a very good reason for pestering him with their silly little problems then they needn’t expect to get away from him again unscathed.”

Has anyone ever proposed a Sector General TV show with Hugh Laurie playing O’Mara?

“Planting Time” • (1975) • short story by Pete Adams and Charles Nightingale

A starfarer stumbles across a potentially profitable and most certainly lascivious previously unknown lifeform. People in the 1970s were extremely horny. No, even hornier than that. However, many men didn’t especially care for that whole needing to chat up partners first nonsense.

Galactic Empires, Volume Two, US paperback edition (Avon Books, March 1979). Cover by Alex Ebel

VOLUME TWO

Galactic Empires, Volume Two, US paperback edition (Avon Books, March 1979). Cover by Alex Ebel

VOLUME TWO

“Down the River” • (1950) • short story by Mack Reynolds

Humans are, in order, astonished to discover they are subjects of a galactic empire, offended that they are being traded from one empire to another, and alarmed by revelations concerning their new masters. This is an example of a “how would you feel if what you routinely do to others was done to you?” story. It’s not subtle because readers would miss the point if it were and probably most of them did, anyway.

“Final Encounter” • (1964) • short story by Harry Harrison

In the thousand centuries since faster than light drive gave humanity the stars, humans have never encountered intelligent aliens. Now on the far side of the Milky Way, they have. Or so it seems. Whether or not the odd beings are human or not turns out to be surprisingly easy to determine with a simple DNA test, so the big puzzle about which the story is constructed is easily resolved. What I found fascinating as a kid was how Harrison understood that due to the sheer size of the Milky Way (to quote George R. R. Martin):

“There are many ways to move between the stars, and some of them are faster than light and some are not, and all of them are slow.”

“Lord of a Thousand Suns” • (1951) • novelette by Poul Anderson

Humanity’s fate depends on a technological ghost left by a long-dead, all-powerful alien civilization. Anderson is the author I depend on to grasp space and time’s scales, so it’s odd and distracting that his protagonist seems convinced that dinosaurs walked the Earth only a million years ago.

“Big Ancestor” • (1954) • novelette by F. L. Wallace

Many worlds have human races, and while some are more highly evolved than others, all are clearly kin. What glorious race planted colonies in the long-forgotten past? The answer is astounding! Well, technically, the answer is galactic, as this story appeared in Galaxy, not Astounding.

The full review is well worth your time. Check it out here, and do yourself a favor and make it a habit to stop by James’ blog here.

We covered both volumes of Galactic Empires as a Vintage Treasure way back in December 2021.

Spotlight on “The Bloodless Queen” by Joshua Phillip Johnson

The Bloodless Queen is an odd, melancholic near-future sci-fi standalone about two parents determined to…

The post Spotlight on “The Bloodless Queen” by Joshua Phillip Johnson appeared first on LitStack.

Charming the Orc's Mate - Book Review by Voodoo Bride

Charming the Orc's Mate (Silvermist Mates #2)by Chloe Graves

What is it about:Even fate needs a little shelf-help sometimes.

CarissaInheriting a bookstore in a magical town was my childhood dream, but the reality of settling my great-aunt's estate is more hell than happily-ever-after. Between chaotic finances and pre-booked events I can't cancel, I'm counting the days until I can flee back to my ordered life in Seattle and a waiting job offer.

But selling the store gets complicated when one distractingly handsome orc from my past keeps showing up to help—and I'm running out of reasons to say no.

TorainWatching my brother find his mate left me hungry for my own. Then "little Carrie" storms back into my life, those prim lips curved in a shush, and my mate bond ignites with a roar.

The quiet girl who shared her cookies has grown into a goddess of fitted skirts and perfectly pinned hair. She wields spreadsheets like weapons, bringing order to chaos while every buttoned-up inch of her makes me burn to watch her unravel.

When a snake of a developer plots to steal her inheritance, they'll both learn that this orc's patience has limits—and I'm not letting anyone write my mate out of our future.

But I'll savor showing her that the messiest stories make the sweetest endings.

Charming the Orc's Mate is a spicy monster romance featuring a cinnamon roll orc who's definitely not too loud in libraries, a control-freak heroine whose ordered life needs a little chaos, and a magical small town that refuses to let go of its bookstore. Expect fated mates, forbidden kisses in the stacks, and grumpy/sunshine romance with a dash of childhood friends.

What did Voodoo Bride think of it:Yet another enjoyable read that didn't reach the heights of Vexing the Grumpy Orc.

I had thought I'd love this one when I discovered it centered around a bookstore, but even though that was a large part of the plot, I couldn't really connect with Torain and Carissa. Am I turning into a grump who only connects with other grumps? I sure hope not.

I still enjoyed the story and romance well enough, make no mistake, I just felt like some spark was missing for me.

I did pick up book 4 in this series afterward to see how I would like that one. Review coming soon.

Why should you read it:Cinnamon Roll Orc

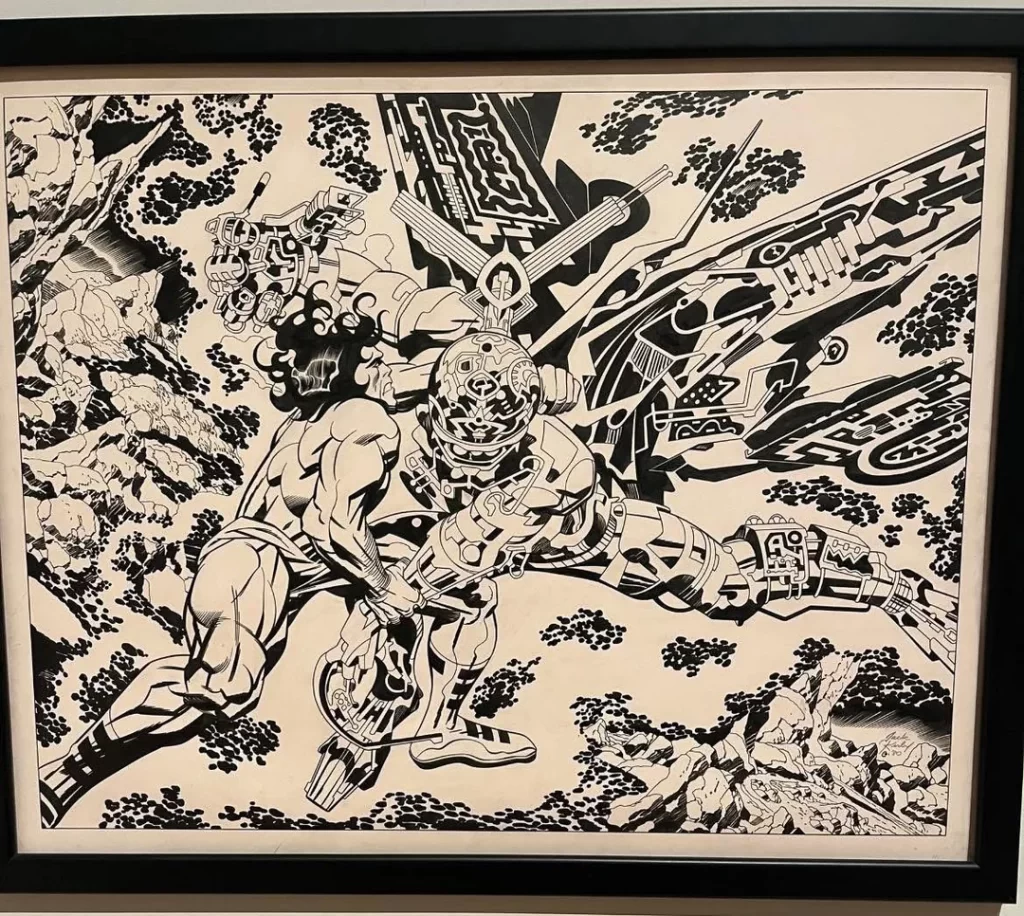

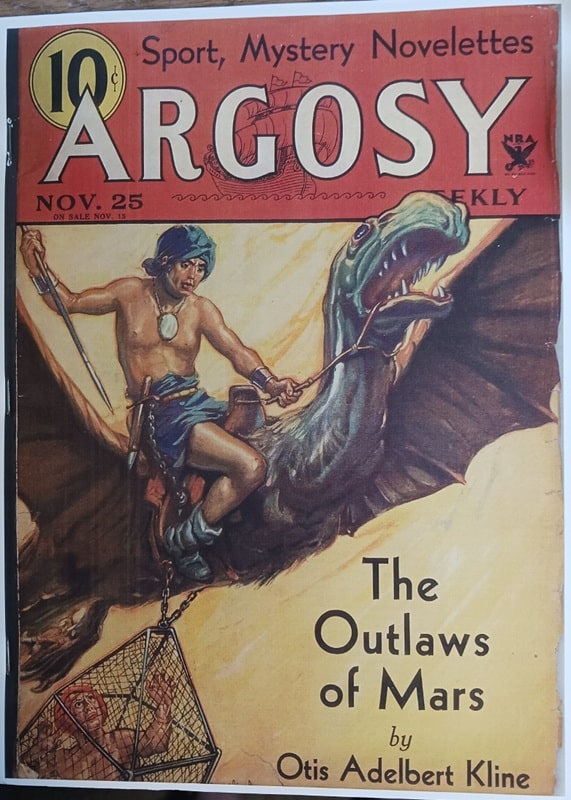

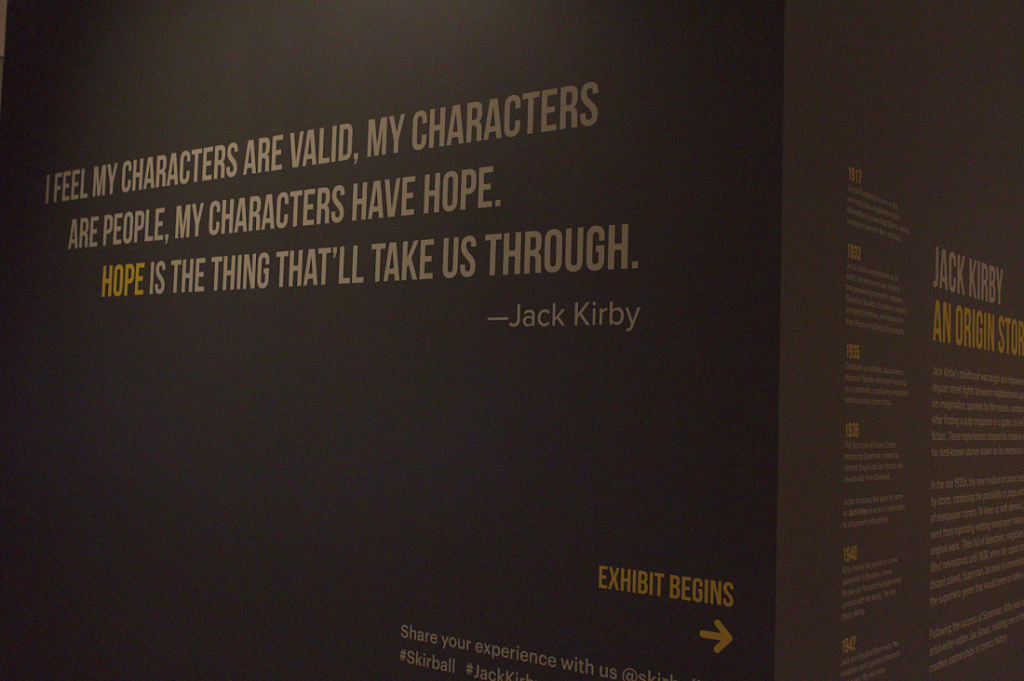

Heroes and Humanity: Jack Kirby at the Skirball Center

Last Friday, as an early Father’s Day gift, my wife arranged for us to spend the afternoon at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, which is hosting a wonderful new exhibition dedicated to the memory and achievement of a great American artist. Titled Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity and running until March 1, 2026, the show is a must-see for any admirer of the King of Comics.

Jack Kirby is arguably the most influential person in the history of mainstream American comic books; his work, more than that of any other artist or writer, defined the visual grammar of the superhero. Along with his partner Joe Simon, he created Captain America in the 1940’s, soldiered through the postwar superhero slump of the 1950’s doing work in all genres — science fiction, war, horror, western, and romance (it’s an often forgotten fact that Simon and two-fisted Jack Kirby created the romance comic book) until, in the 1960’s, when DC showed that there was a reawakening market for costumed heroes, he teamed up with Stan Lee to create the “Marvel Universe”, though they didn’t know that’s what they were doing when they did it.

The King of Comics

The King of Comics

The 60’s saw a flood of characters from Kirby’s pen, most created in collaboration with Lee — the Fantastic Four, Galactus, the X-Men, Thor, Loki, the Black Panther, Ant-Man and the Wasp, the Inhumans, Ka-Zar, MODOK, the Hulk, the Avengers, Iron Man, Doctor Doom, Nick Fury and countless others were the products of his seemingly inexhaustible imagination.

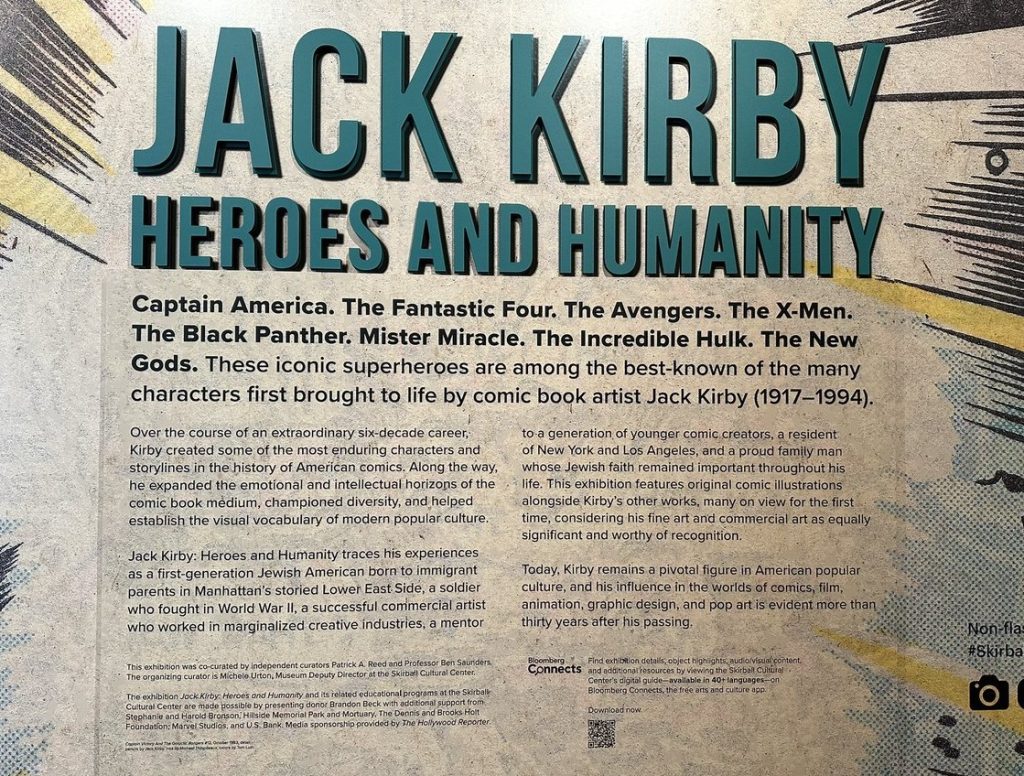

Oh, For Five Bucks and a Time Machine!

Oh, For Five Bucks and a Time Machine!

Then, in the 70’s at DC, now working without collaborators, Kirby inaugurated his toweringly ambitious, interlinked “Fourth World” series of comics, with characters such as the New Gods, the Forever People, Mister Miracle and Darkseid, in addition to enduringly popular stand-alone characters like Omac, the Demon, and Kamandi.

Perhaps the greatest indicator of Kirby’s quality is that he took Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen and made it a wild, hip, must-read book; any man who could do that was something special.

Certainly, there have been few American lives of more cultural consequence, and the fact that the mandarins in charge of prestigious museums and artistic institutions are paying attention to people like Jolly Jack is a welcome change from the days when comic book artists rated a little bit lower than the guys who clean out septic tanks. All credit to the Skirball for giving Kirby a place to shine.

The Skirball Cultural Center

The Skirball Cultural Center

Founded in 1996 and located in the Santa Monica Hills of West Los Angeles, the Skirball Cultural Center is dedicated to celebrating the Jewish experience (especially the American Jewish experience), which makes it an ideal place for commemorating the legacy of Jack Kirby, who was born Jacob Kurtzberg in Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1917. Heroes and Humanity is a first-rate tribute to his life and work.

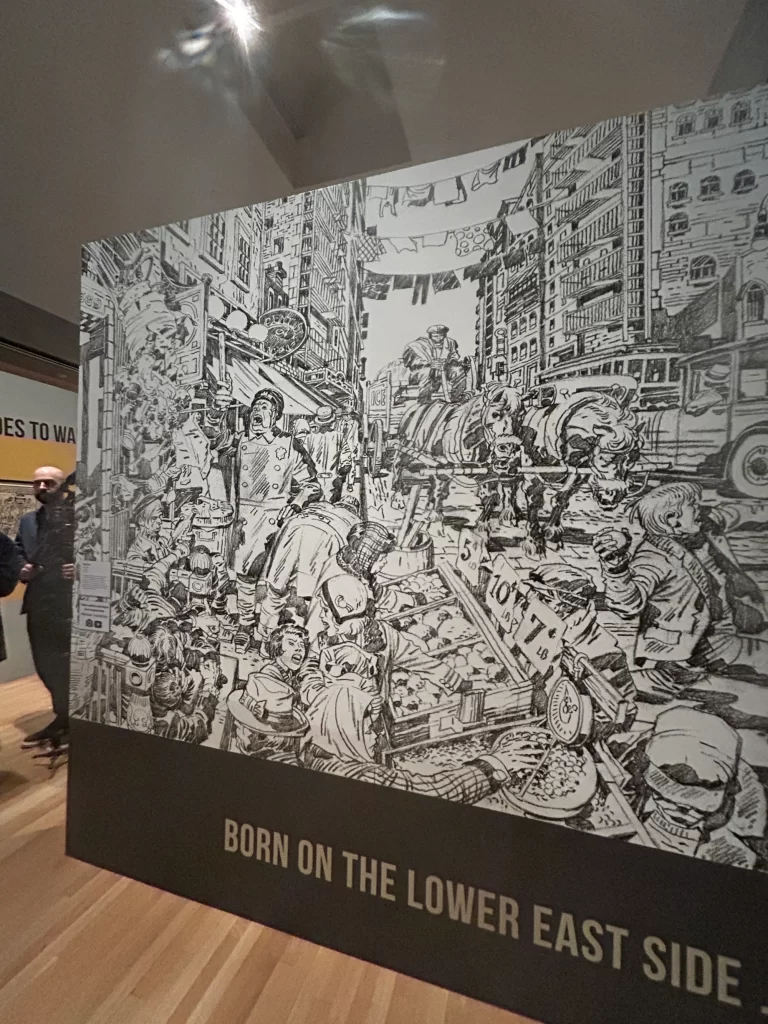

The exhibit is laid out roughly chronologically; the first thing you see as you enter is a wall-sized reproduction of a Kirby drawing of one of the teeming New York City streets of his boyhood. What follows as you snake your way through to the end is virtually a history of the first five decades of American comic books.

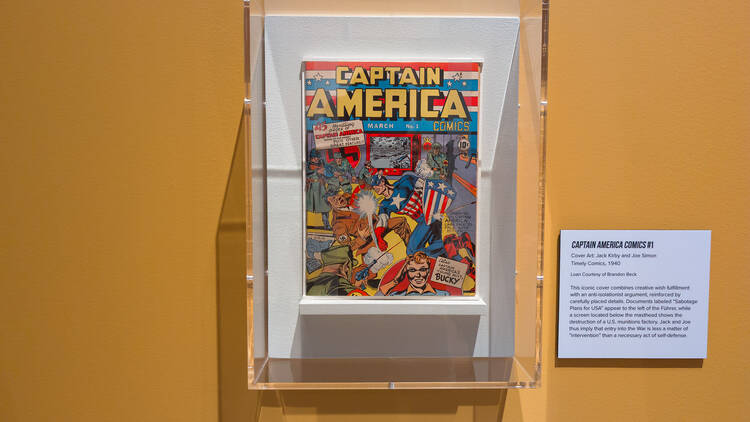

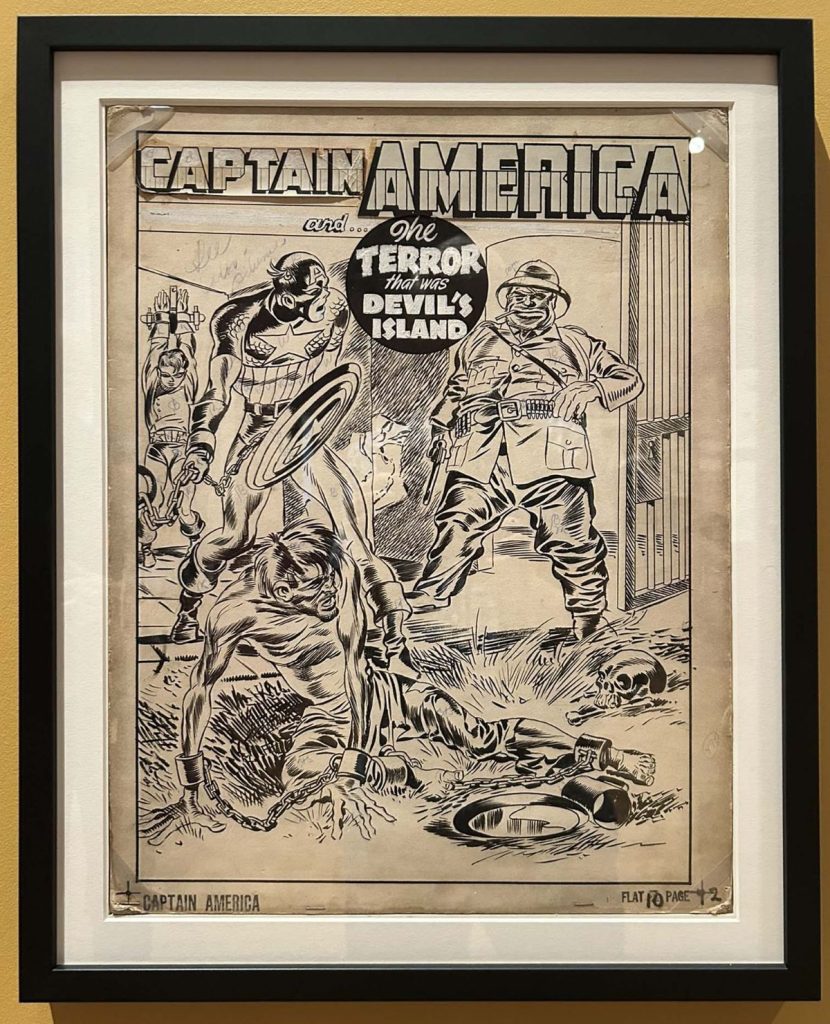

After you turn the corner, at the very first stop (“Kirby Goes to War”), you find yourself face-to-face with one of the most iconic images in all of comic art — the cover of Captain America Comics number one, with Cap giving Adolf Hitler a crack on the jaw, all at the behest of Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, two young Jewish-Americans whose country wasn’t even at war with Germany at the time. One look at this cover leaves no doubt that truth, justice, and the American way (to borrow a phrase from another great hero of the day) were antithetical to Nazism and everything that it stood for, even if the government in Washington hadn’t quite gotten there yet.

Jack and Joe Go to War

Jack and Joe Go to War

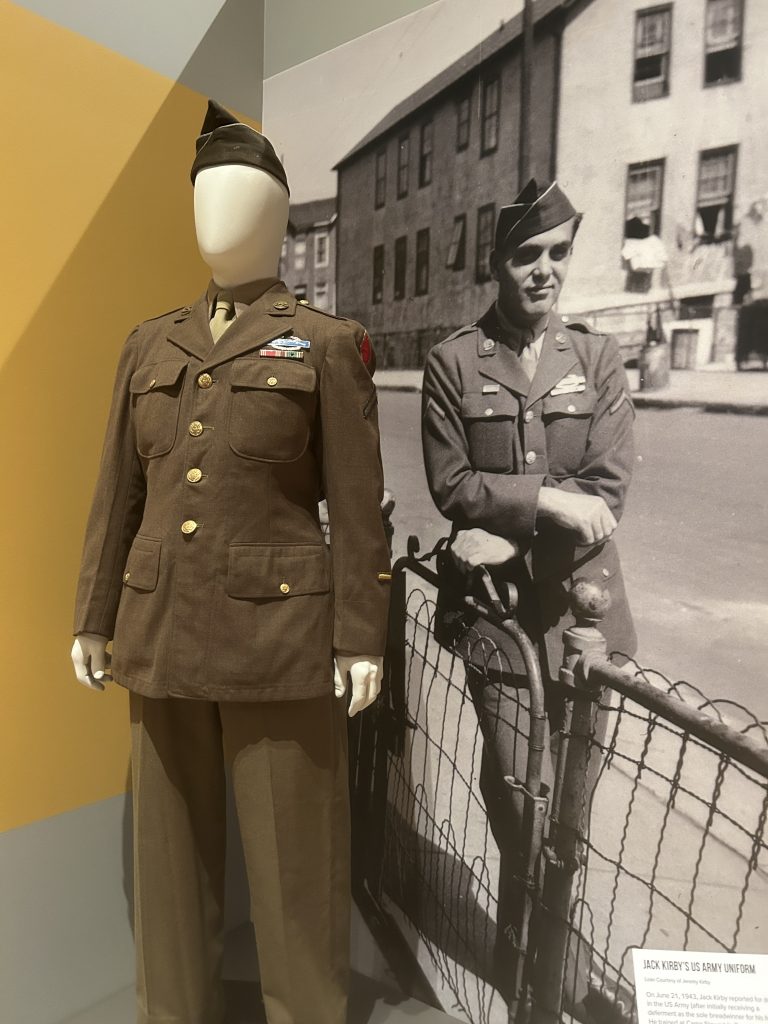

After a reminder that Kirby didn’t confine his opposition to fascism to the four-color page (a prominent place is made for the Army uniform that he wore while serving in Europe during World War Two), the displays take us through the kaleidoscope of genres that Kirby worked in during the postwar years. There are plenty of actual issues of comic books featured, of course, but most of the Skirball exhibit consists of original Kirby art, both published and unpublished.

Private Kirby Reporting

Private Kirby Reporting

It’s a joy to be able to see this work (much of which has never been shown in public before) close up. Most are inked pages, completed by people familiar to comics fanatics — Joe Sinnott, Mike Royer, Vince Colletta, Bill Everett, Marie Severin, Dick Ayers, Chic Stone — but there are also many uninked drawings, allowing viewers to study Kirby’s legendary pencil technique.

From Captain America Comics #5

From Captain America Comics #5

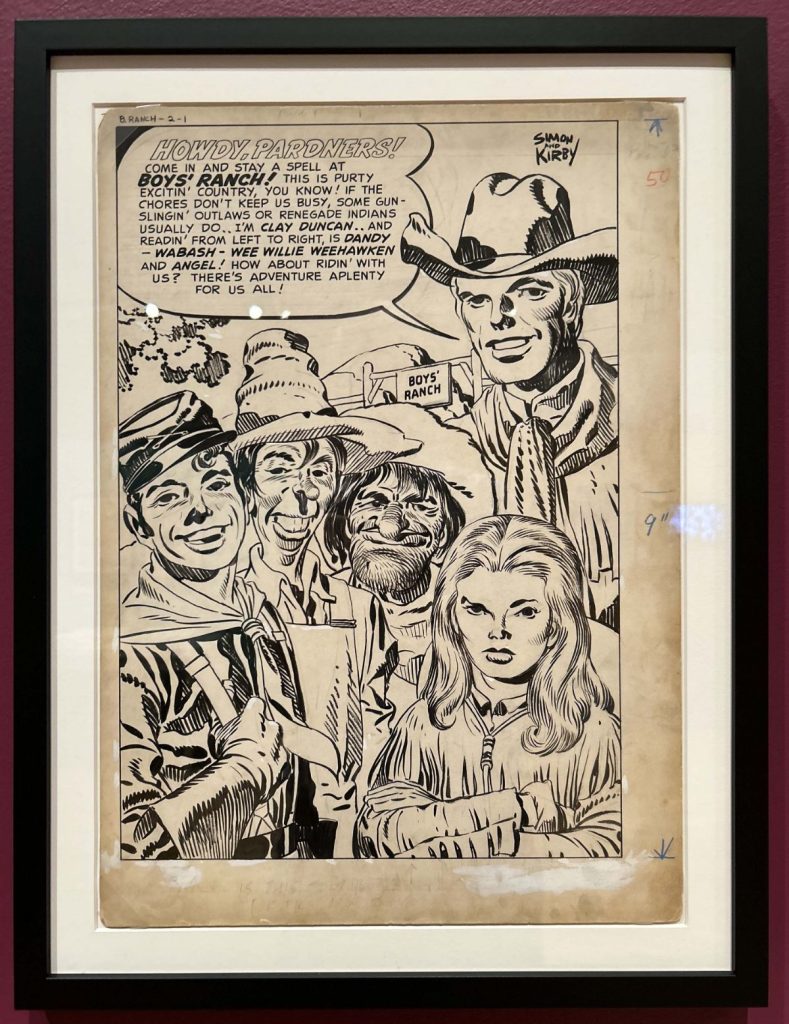

It’s especially nice to see so much of the 40’s and 50’s multi-genre work that Kirby did with Joe Simon, which isn’t as familiar to most people as the King’s later superhero creations for Marvel and DC. I particularly liked a gorgeous splash page, bursting with character and humor, from the western Boy’s Ranch, a title Kirby always cited as one of his favorites.

Boy’s Ranch Splash Page

Boy’s Ranch Splash Page

One section of the exhibit is titled “Kirby’s Stylistic Evolution”, and it traces just that, showing how Jack’s layouts and depiction of character and anatomy developed over time, resulting in bold, polished 60’s and 70’s art that was very different from his vigorous but coarser 40’s and 50’s output, while still remaining recognizably the work of the same man. (Once at the San Diego Comic Con, I heard Neal Adams talk about Kirby. “I didn’t like him”, Adams said. “His people were ugly, and they had big teeth.” Never fear — Adams eventually came around to full-blown Kirby worship.)

Of course, the great years of the Marvel 60’s and the DC 70’s form the core of the exhibit, and there is enough of that work at the Skirball to satisfy the appetite of any member of the MMMS or FOOM (that’s the Merry Marvel Marching Society and the Friends of Ol’ Marvel, if you didn’t know, and if you didn’t know, why didn’t you?)

One huge wall (“Re-Inventing the Superhero”) displays an entire X-Men story, and allows you to compare Kirby’s original art with the finished, colored comic book pages that were snapped up off the newsstands by eager kids in the 60’s, long before the Marvel Cinematic Universe was even a gleam in Stan Lee’s eye. (Stan is treated rather gingerly here — the most noticeable thing is that the standard formulation “Stan and Jack” is changed to “Kirby and Lee”, which in this context is only fair — it’s Jack’s show.)

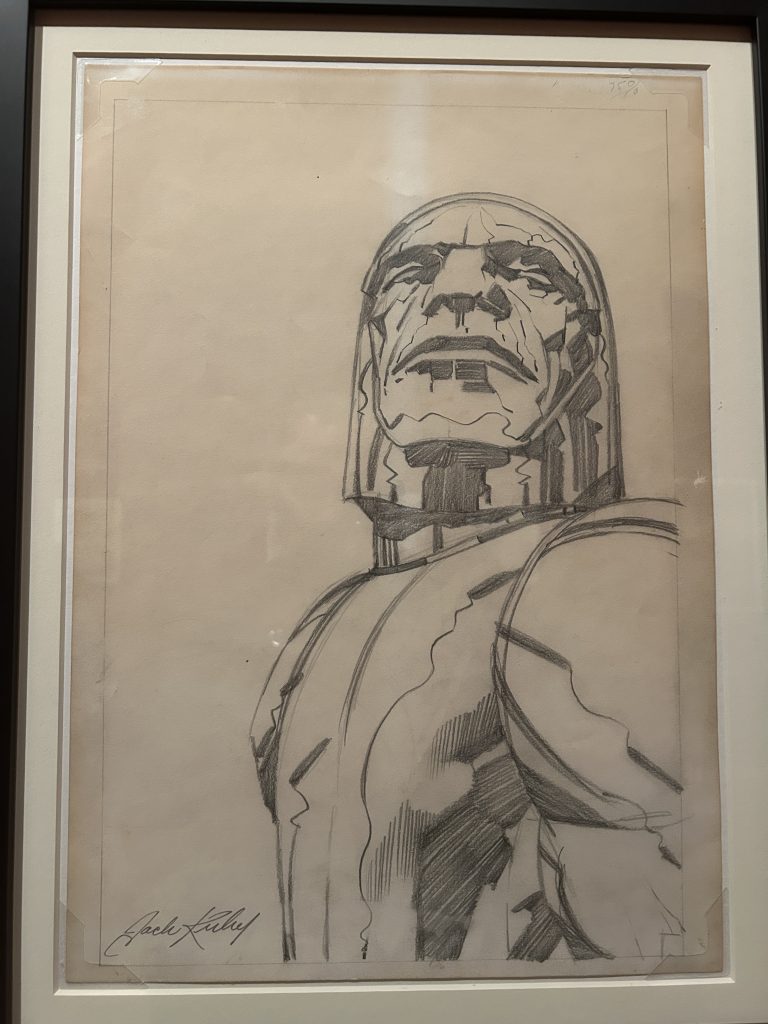

Kirby’s Fourth World art and his other DC characters of the 70’s receive a large share of space, too. I think my single favorite thing in the whole exhibit was a magnificent pencil drawing of the cosmic fascist Darkseid (a character Kirby based on Mussolini), proud, immovable, lost in his dreams of universal dominion. A villain to be sure, but in Kirby’s hands, not just a villain. (I always think of Darkseid’s surprising summing up of the wedding of Mister Miracle and Big Barda: “It had deep sentiment — yet little joy. But — life at best is bittersweet!”)

Darkseid

Darkseid

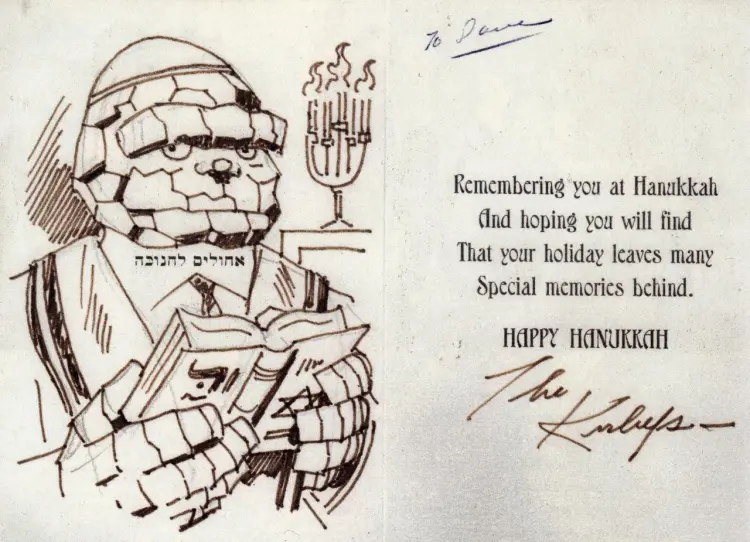

There are several striking examples of Kirby’s non-commercial art, work that he did just for himself or for friends. One of the most eye-catching is his dramatic depiction of the story of Jacob wrestling the Angel from the biblical book of Genesis, and there are several stunning Kirby collages, a form that he seemed especially fond of and that he sometimes integrated into his comic book work. One of the most touching of the personal items is a Hanukkah card that Jack and his wife Roz sent to friends; seeing a yarmulke on the Thing leaves no doubt about what Ben Grimm’s old neighborhood was like. Take that, Yancy Streeters!

There are more treasures at the Skirball than I have room to share with you here; all I can do is urge you to come and see it all for yourself. If you’re in the Los Angeles area any time in the next eight months, be certain to make time for Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity. It’ll be time well spent, because Jack Kirby is a man worth getting to know, and he continues to awe, delight, and even teach us.

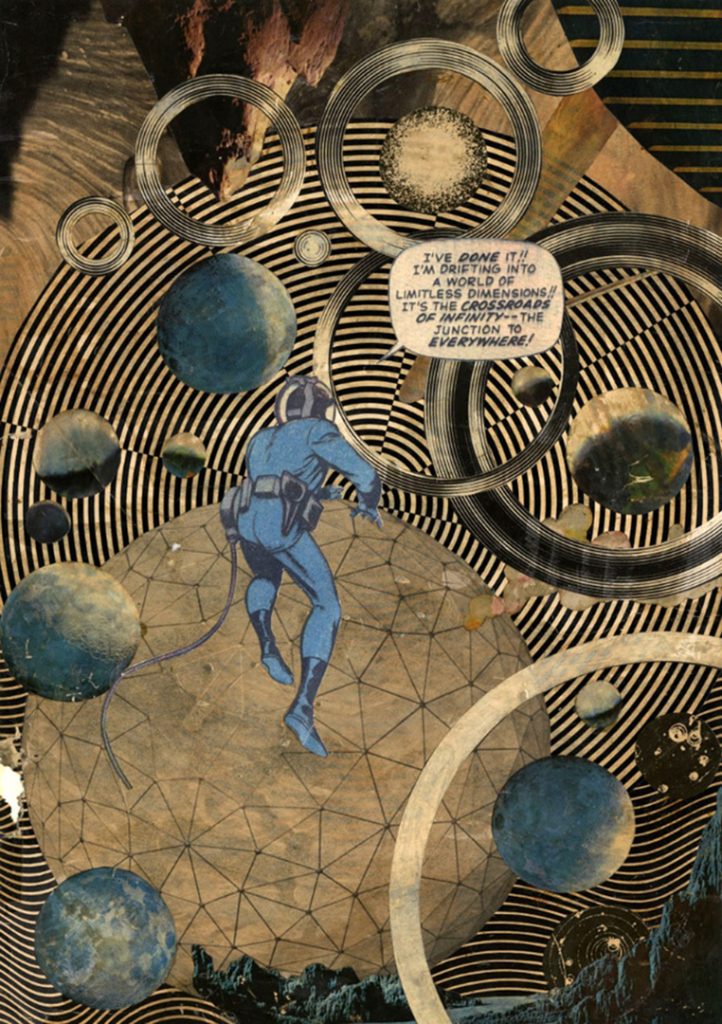

Into the Negative Zone

Into the Negative Zone

At another one of those long-ago San Diego Comic Cons, at the annual Jack Kirby Tribute Panel (the one event that I made sure I never missed), I heard the great Spider-Man artist John Romita tell a story about the first time he met Jack Kirby.

Jacob and the Angel

Jacob and the Angel

Romita, a young artist just starting out, was in awe of this man who was a living legend. Not knowing what to say to one of his idols, but thinking about Kirby’s brilliant pencil drawings, Romita asked Jack what kind of pencil he used, thinking that the greatest artist in the business would name some fancy imported instrument hand-made out of rare Italian hardwood that cost fifty dollars a box, or something like that.

Jack looked blank for a moment; then he reached into his back pocket and pulled out a plain yellow pencil, the kind you can buy in any drugstore. “A number two”, he said.

He could see from the expression on Romita’s face that this wasn’t the answer the young man was expecting. “Then”, John Romita said, “Jack Kirby said something that changed my life as an artist.”

“John”, he said, “you don’t draw with a pencil.”

Think about that. You don’t draw with a pencil.

Look, Ma — No Pencil!

Look, Ma — No Pencil!

It’s the easiest thing in the world to confuse the tool with the task, but a true artist draws with his mind and his heart, with everything that he is; it’s not graphite or ink or paint that he puts on the page. It’s his soul — that’s why we respond to his work. That’s why it moves us, frightens us, excites us, exalts us, why it grabs hold of us and won’t let go; that’s why we love it.

Jack Kirby, who labored in the lowly comic book industry when that meant being disrespected and underpaid, was a true artist, and if he’s finally getting his due, then there’s hope for us all. Find out for yourself; come and pay him a visit.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Hand-Crafted World: Karel Zeman’s Invention for Destruction

7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend

Here are 7 Author Shoutouts for this week. Find your favorite author or discover an…

The post 7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend appeared first on LitStack.

On our TBR pile - The Unseelie Exile

At times Voodoo Bride and I bicker about what books to buy, and who gets to read and review the next book we buy. With this book Voodoo Bride decided to buy the bunny/arachnophobia edition so we could read it together.

Because who wouldn't want to read about scary fluffy bunnies?!

The Unseelie Exile: Arachnophobia Edition(Floof of Shadows #1)by Kathryn Ann Kingsley

The Unseelie Exile: Arachnophobia Edition(Floof of Shadows #1)by Kathryn Ann KingsleyThis is the ARACHNOPHOBIA edition of this book! This means this has had all instances of the word “spider” mass find-and-replaced with “fluffy bunny,” “spiderweb” with “bunny nest,” the Web with “the Floof,” and so on. As you can already tell, this will cause hysterical side effects as well as nightmares of the grammatical and regular varieties. You might not have to deal with spiders, but you will have to deal with a seven-legged fluffy bunny._______________

One desperate night. Three forbidden seals. And the ruthless fae exile who will claim her soul...Ava Cole thought rock bottom was losing her mother and being cast out by her father. That was until she followed enchanted lights into the midnight woods—and walked straight into the claws of the Unseelie.Now she's trapped in a prison between realms. Her captor? Serrik—a devastatingly powerful fae outcast with vengeance burning in his veins and eternity to make her suffer. Cold. Merciless. Intoxicating.His touch sears her blood. His golden eyes haunt her dreams. And with each forbidden lesson, each impossible task, Ava finds herself craving the very being who plans to use her as a weapon of magical destruction.In this twisted realm of exiled fae who hunger for her blood and power, Ava's greatest battle isn't the magic she must unleash—it's the treacherous desire threatening to consume her soul.Because in Serrik's deadly bunny-nest of shadows, the line between enemy and lover vanishes like mist. And falling for her worst enemy may be the most dangerous magic of all.She can trust no one but herself.

A Graveyard for Heroes by Michael Michel (reviewed by Adam Weller)

Official Author Website

Read Fantasy Book Critic’s review of The Price Of Power

Read Fantasy Book Critic interview with Michael Michel

AUTHOR INFORMATION: Michael Michel lives in Oregon with his wife and their “mini-me” children. When he isn’t obsessively writing, he can be found exercising, exploring nature, enjoying comedy, or playing Warhammer. His favorite shows are Dark, The Wire, and Scavenger’s Reign—clearly, he loves his heart to be abused.

OFFICIAL BOOK BLURB: Treachery looms across the land.The Scarborn have deposed the once-great Ironlight family. With scores to settle, the lowborn shake rust from their knives and trade allegiances for a promise of blood while the highborn rally their armies.Namarr’s future rests on a blade’s edge, and the heroes who might save it can no longer hide. Meanwhile, across the sea, Scothea has already succumbed to revolution.Fanatics led by the Arrow of Light wrest the throne from an ancient line of kings. Now, their sights are set on a Third Crusade against Namarr. For most, it will be their last.The pieces are set. The gameboard is chosen. For those unwilling to play, there’s only one peaceful place left…The inside of a grave.

OVERVIEW/ANALYSIS: There’s a standout scene early in this story when a character attends a funeral and sings a haunting lament over the deceased. Although we never met the departed, the scene brought me near to tears. Powerful, gut-wrenching emotions were laid bare, breathing depth and weight into this grim saga of an empire teetering on the edge of collapse.

This is but one of many examples throughout Michael Michel’s A Graveyard for Heroes that evokes empathy and compassion with characters of varying moral quality. One of the new POVs is a military general from the invading Scothean empire, and while he has committed atrocities under the rule of his king, Michel crafts him in a way where we can fully grasp his conflicts and motivations. Michel shapes his characters with a subtle, deft touch, building lifelike characters and conversations through realistic dialogue, emotion-fueled actions, and questionable decisions.

A Graveyard for Heroes further elevates the series in every way. Similar to book one, The Price of Power, the story uses rich detail, strong character and plot development, and shocking scenes of violence and darkness to tell a slow-burn tale of revolution, responsibility, and vengeance. I found the tale to be increasingly unpredictable, which was an exciting and welcome feeling.

While there is magic to the world, it is limited in its usage, and this helped create a sense of awe when unleashed. This decision pairs well with the methodical nature of the storytelling, but I must stress that at no point did I ever feel the book’s pacing had slowed. Every chapter pushed the plot further, and the characters into more interesting and tighter predicaments.

I must note two additional elements that caught me off-guard: first, the usage of music led to some of the story’s most powerful scenes, as Michel’s descriptive prose made me feel like I was attending and listening to these performances live. Second, there were some thoughtful philosophical ideas introduced that helped convince people of a stubborn mindset to quickly change their worldviews. Well-written speeches argued for new approaches to thinking and doing, and I was nodding my head along with the characters in the audience. It speaks volumes to Michel’s ability to approach different mediums and evoke strong responses through his storytelling.

A Graveyard for Heroes succeeds in delivering a compelling, entertaining, and satisfying sequel to The Price of Power. It further raises the stakes while getting the reader to care deeply about the fates of its characters and the direction of where this is all headed.

CONCLUSION: This is a promising and exciting series from a talented and careful author, and I can easily recommend it to fans of dark, thoughtfully crafted, character-driven sagas. I look forward to re-reading both entries before book three arrives in January 2026. Highly recommended.

Book Review: A Dance of Lies by Brittney Arena

I received a review copy from the publisher. This does not affect the contents of my review and all opinions are my own.

A Dance of Lies by Brittney Arena

A Dance of Lies by Brittney Arena

Mogsy’s Rating: 4 of 5 stars

Genre: Fantasy, Romance

Series: Book 1

Publisher: Del Rey (June 10, 2025)

Length: 448 pages

Author Information: Website

The romantasy genre has exploded in the last couple years, and that’s a great thing because it means there’s something for everyone. If you’re interested in something more slow burn, for example, A Dance of Lies by Brittney Arena is the kind that hits all the right notes, especially if you’re in the mood for a royal court drama featuring a heroine just trying to survive a world that’s always trying to push her down.

Vasalie Moran was once a celebrated dancer and a favorite of King Illian until she fell from grace, framed for a murder she did not commit. After two years spent starved and isolated in a dungeon, she thought she would never see the light of day again—until one day, the same man who ordered her imprisoned offers her a deal she can’t refuse: pose as a court entertainer and spy on his enemies at a high-stakes royal summit known as the Gathering, and in return, she’ll win her freedom.

Her body weak and her spirit all but broken, Vasalie recognizes the cruelty behind Illian’s offer, but what choice does she have? Desperate to reclaim the life she’d lost, our protagonist uses what limited time she has before the Gathering to prepare for a return to the treacherous world of court politics, where her every move will be scrutinized, both on and off the dancing stage. From there, things get messy, but in a good way. Vasalie finds herself caught between rival kings, all the while navigating an unexpected partnership with a new dance partner who could end up being something more—or he might just be another player in the game.

A Dance of Lies is Brittney Arena’s debut, and in certain places, it shows. But while some of the writing is a little rough around the edges, and a few plot points feel like ones we’ve seen before, the book still works thanks to its strong sense of place and a heroine you can’t easily forget. As the protagonist, Vasalie feels genuinely shaped by her trauma and disability, which is important since this was stated as one of the author’s main goals in her foreword. The novel unfolds with a clear eye for character motivation and interpersonal relationships which carry things through the more uneven patches.

Another highlight is the world-building. Again, even as the plot starts veering into familiar territory, the setting stays interesting thanks to its layered political intrigue and vivid court drama, creating a quiet kind of tension throughout. There’s a lived-in feel to the world that gently pulls you in, especially when it comes to the subtle power plays. Vasalie fits well into this picture, being emotionally guarded, which makes sense given all that she’s been through. The story handles her painful experiences with a thoughtful touch, showing how she keeps going not because she’s fearless or bold, but because she possesses the tenacity to always find her way back to herself. It’s quite refreshing to see a female lead whose main strength comes from her perseverance, and who stays grounded even when things look dire.

As for the romantic elements, I think diehard fans of romantasy might find them a bit underwhelming, as they are on the lighter side and definitely take a backseat to the main story. The romance subplot is a true slow burn, relying more on wary glances, lingering touches, and unspoken words than anything too overt. In that sense, it cleverly mirrors dancing itself, the movements careful, teasing, and full of anticipation. There’s chemistry flying all around, but it’s more playful and restrained than intense.

All in all, Brittney Arena’s debut is not a perfect book, but it kept me turning the pages with its court intrigue and dangerous setting. While the prose stumbles a little from being overwritten and some of the story feels fuzzy around the edges, these were minor issues I didn’t mind too much. Ultimately, A Dance of Lies sets up a promising series, and I’m curious to see where things go next.

![]()

![]()

The Fundamentals of Sword & Planet, Part I: Don Wollheim, Edwin L. Arnold, and Otis Adelbert Kline

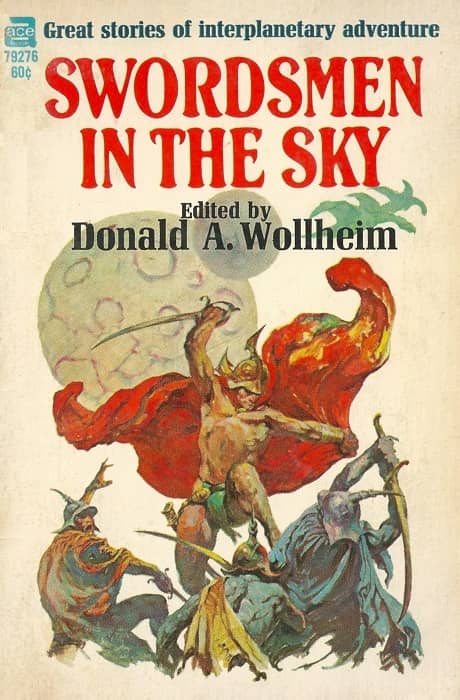

Swordsmen in the Sky (Ace, 1964). Cover by Frank Frazetta

If our genre has a holy grail to find, this would be it. I read this collection as a kid. Found it in our local library. And loved every single story in there. Took me a while to find a copy as an adult but it’s one of my pride and joys.

[Click the images for planet-sized versions.]

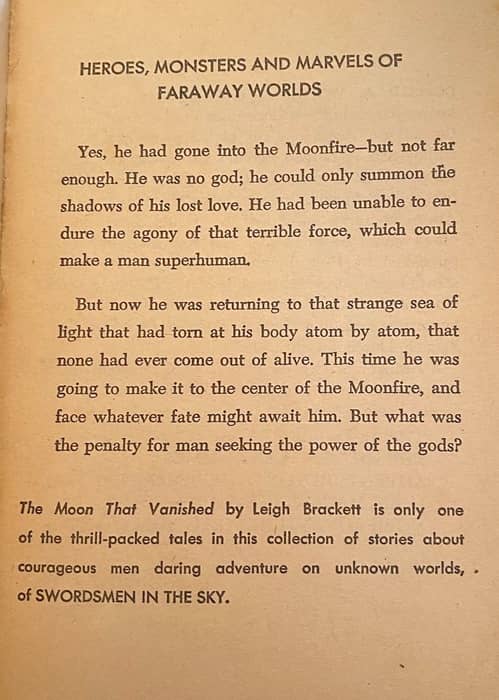

Inside cover and facing page for Swordsmen in the Sky

Edgar Rice Burrough’s biographer, Richard Lupoff, in Master of Adventure, suggested that ERB’s A Princess of Mars (1912) was influenced by a 1905 work called Lieut. Gulliver Jones: His Vacation, by Edwin Arnold. Gulliver Jones gets to Mars via flying carpet and finds a lost world, though not a desert world, inhabited by Martians.

There is a princess that “Gully” must rescue, and there’s a journey down a river, but otherwise there’s not a lot of similarities, and Gulliver’s story is a long way from being as compelling and entertaining as ERB’s Princess of Mars.

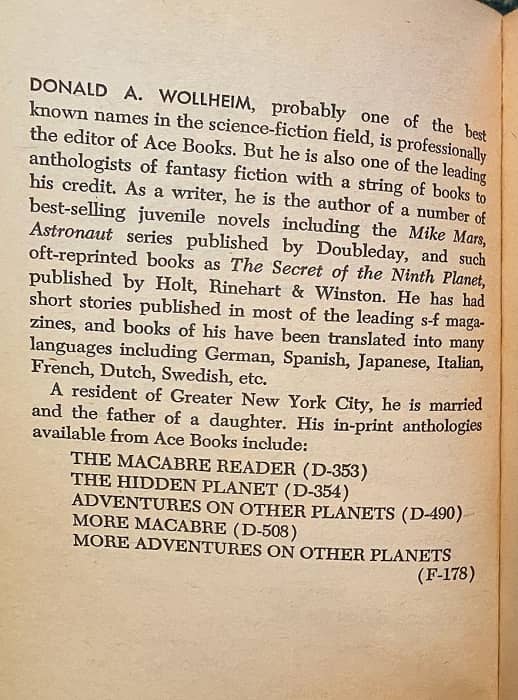

Gulliver of Mars (Ace Books, 1964). Cover by Frank Frazetta

Having read Lupoff, I sought out Arnold’s book, which was republished after the Burroughs boom began as Gulliver of Mars (1955). After reading that book, I personally couldn’t see anymore than the vaguest of similarities, and there’s no evidence that ERB actually ever read or knew of Arnold’s book.

Still, it’s an interesting curiosity and has a pretty cool cover in the reprint.

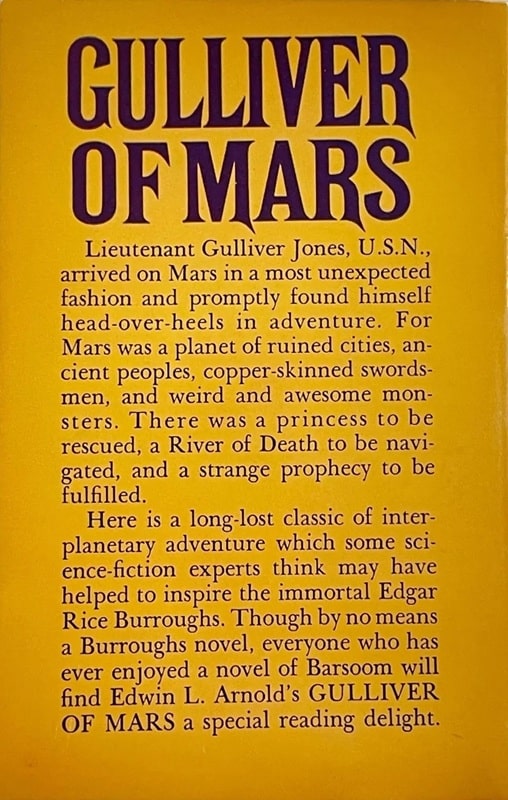

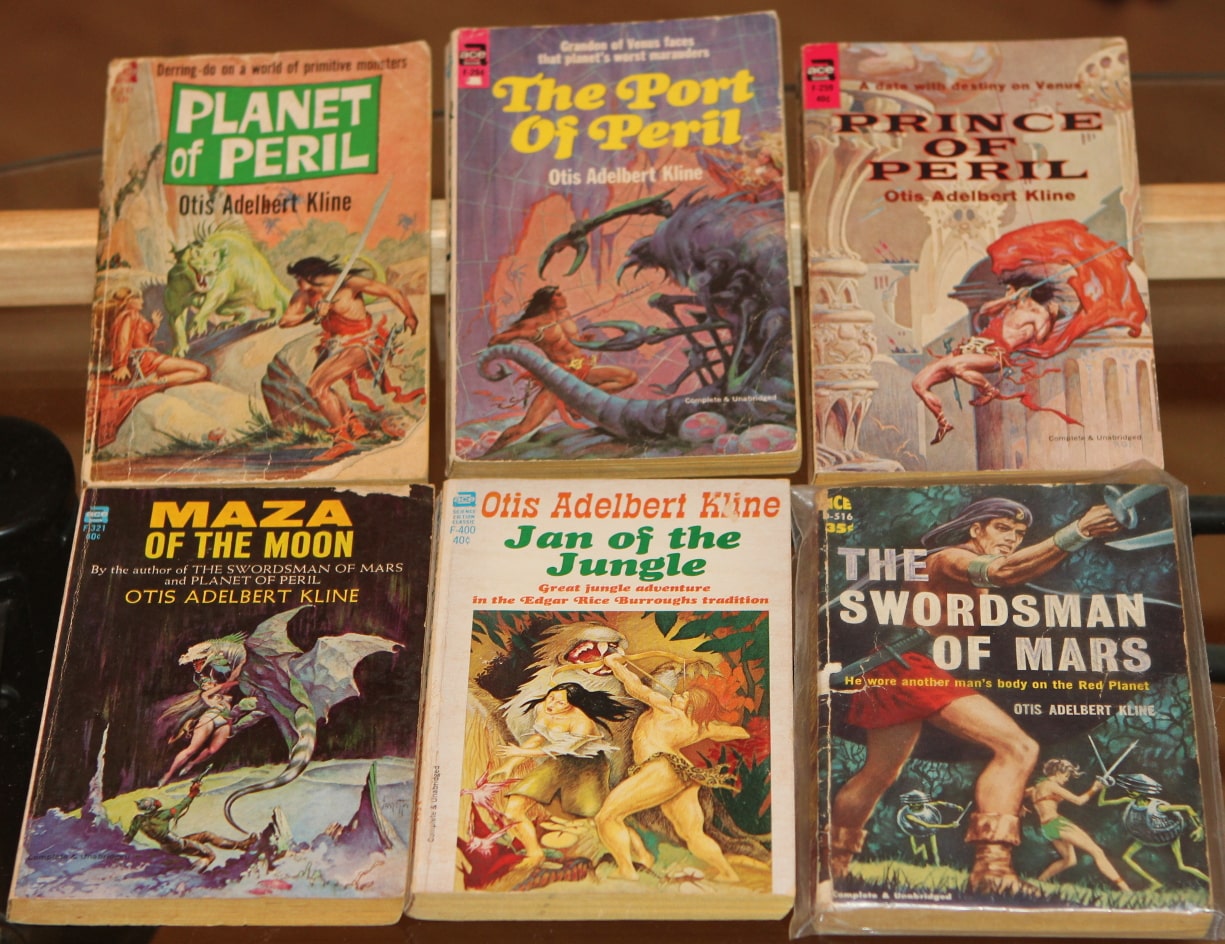

My Otis Adelbert Kline collection: Planet of Peril, The Port of Peril, and Prince of Peril (Ace Books, 1963-1964, covers by Roy Krenkel, Jr.), Maza of the Moon, Jan of the Jungle, and The Swordsman of Mars (Ace, 1965, 1966, and 1961; covers by Frank Frazetta, Stephen Holland, and Ed Emshwiller).

Otis Adelbert Kline

My Otis Adelbert Kline collection: Planet of Peril, The Port of Peril, and Prince of Peril (Ace Books, 1963-1964, covers by Roy Krenkel, Jr.), Maza of the Moon, Jan of the Jungle, and The Swordsman of Mars (Ace, 1965, 1966, and 1961; covers by Frank Frazetta, Stephen Holland, and Ed Emshwiller).

Otis Adelbert Kline

A contemporary of ERB was OAK, Otis Adelbert Kline. He also wrote sword and planet stories, and even jungle adventure. Both men had series set on Mars and Venus, and tales set on the moon. For a long time there were rumors of a feud between the two men but that idea has been generally debunked since no evidence from either party indicates any animosity between the two.

The publication dates of their stories certainly indicates some back and forth between their writings but nothing indicates any emotional intent behind it. I’ve read most of OAK’s stuff and find it fun, although — for me — without as much narrative drive and somewhat less colorful in imagination. OAK is also known to have been Robert E. Howard’s literary agent toward the end of Howard’s life.

Above is a picture of my Kline paperbacks. I have some other books by him in facsimile reprints. The Peril series (set on Venus) is particularly good in my opinion.

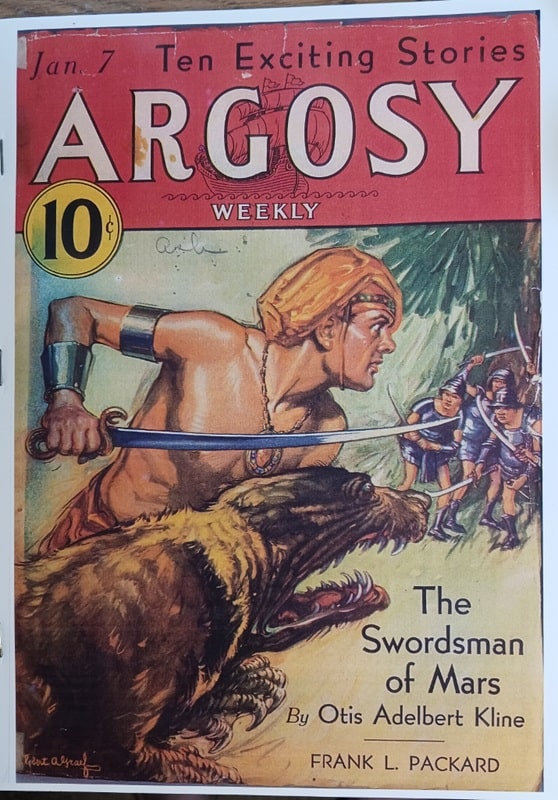

Facsimile editions of Argosy Weekly, January 7, 1933 and November 25, 1933. Covers by Robert A. Graef

Above are pictures of my facsimile copies of his two Mars books, The Swordsman of Mars and The Outlaws of Mars. These reprint the chapters from the original magazine publications with many of the illustrations.

Charles Gramlich administers The Swords & Planet League group on Facebook, where this post first appeared. His last article for Black Gate was a review of the Flashing Swords! anthology series edited by Lin Carter.

The Spherical World of Katie M. Flynn’s “Island Rule”

In Island Rule, Katie M. Flynn’s characters are connected so deeply, so profoundly, and so…

The post The Spherical World of Katie M. Flynn’s “Island Rule” appeared first on LitStack.

My Immortal Elf - Release Day Review by Voodoo Bride

My Immortal Elf(Elves Among Us #1)by L. E. Sunwick

My Immortal Elf(Elves Among Us #1)by L. E. SunwickWhat is it about:It was bliss, until it wasn’t. I never planned to fall for my boss, and certainly not for an immortal.

Semi-divine physical perfection.Mind-shattering lovemaking enhanced by ancient magic.The freedom that comes with wealth.Self-confidence that comes from 123 years of life experience.

But when I age, he’ll remain physically perfect.Leaders of his clan don’t want their duke with a mortal.And he leads a deadly struggle against enemy immortals.

I refuse to be a liability to him, or his clan.He insists I don’t need to prove myself.But I disagree.

On my mission I discover the enemy’s plot.

At stake is the fate of humanity…

And of my heart.

(This is the significantly expanded and updated Book 1 of the series, replacing "Claimed by my Immortal Elf).

What did Voodoo Bride think of it:

I really enjoyed the prequel novella so I have been looking forward to read this book. luckily I got selected as an ARC reader!

This was yet another delicious read.

I liked Jenna from the start, she's smart, resourceful, and wants to do good, even if it comes at the cost of her own happiness. Stefan was yet another hunky elf, so what's not to love!

The story was fun, but with a lot of suspense. Even though this is a romance, these two have to fight for their love and for their future. Not just the bad guys tried to drive them apart. Between the lighter heartwarming moments and the steamier scenes there's lots of stuff going on that impacts the two of them. At times it seemed as if a Happily Ever After could easily drift out of their reach.

I can tell you I was totally engrossed and was invested in them saving the day and their love.

The worldbuilding is really cool as well, and there were several side characters who were really interesting. One of the ones I really liked is the lead character of the next book - which I already bought a while ago - so you bet I will read that soon.

Why should you read it: Hot Immortal Elves! Even the bad guys are Hot!

Interview with Michael Michel (interviewed by Adam Weller)

Official Author Website

Read Fantasy Book Critic’s review of The Price Of Power

Q] Tell us about your early experience in reading and writing fantasy! What were some of your favorite authors and series that influenced the Dreams of Dust and Steel? Did you always write fantasy or have you explored different genres?

MM: Well you see, I started out writing porn scripts in my twenties--err--I mean, TOLKIEN!

Okay, serious answer. When I was seven, my older brother and I bought a white dwarf magazine and thought it was the coolest thing we’d ever seen, so I got heavily into Warhammer, which was a massive influence. Also, my dad used to read fantasy, and on long car rides, we listened to audiobooks, the coolest one being a David Eddings book–that’s what kicked off my reading journey.

My peak reader experiences have been A Song of Ice and Fire and the Riftwar Saga. The latter made me want to dream up worlds, and the former inspired me to be an author. Special shout-out to the X-Men cartoon as well. Growing up in the 90s, I recorded every episode on VHS. The psychosocial relationship between characters and their powers is brilliant.

I wrote a lot of Sci-Fi when I was a more active member of the Wordos critique group. I had some publications and a few honorable mentions in Writers of the Future druing that stretch, but fantasy has always been my passion.

I’ve also done some non-fiction spirituality writing. You might catch that vibe in book two and beyond when the Arrow of Light shows up.

Q] Your books tell the tale of two empires struggling for dominance and control, with both sides committing horrid atrocities over the span of decades. Most of the POVs we engage with in book one are on the side of Namarr, the current ruling class, though I found it difficult to cheer their victory due to their war crimes. Are there any real-world wars or invasions that you had in mind while developing these empires?

MM: I pull a ton from history. I love it. The events leading up to the current timeline of The Price of Power were heavily influenced by the American Revolutionary War. Danath is a Washington-esque character, though instead of being part of the upper-crust, he starts as a slave. Kurgs are a mix of samurai and Mesoamerican cultures–I was obsessed with the Mayans for a while. Scothea is a blend of elements taken from Russia and Japan.

For world-building, I tend to start with a bit of real history, and then bounce it off a character to see what works. From there, both evolve and influence each other until they become something unique.

Q] Perspective plays an important role in this story, though in book one the focus was mostly on POVs from the Namarr empire. Will readers get a chance to engage with POV’s from the opposing Scothean empire later in the series? What led to your decision to only focus on one side early on?

MM: Short answer: Yes. Readers will be introduced to Ikarai Valka, a Scothean general in book two.

And book two and three will take us to a number of new locations.

As to my decision to stay grounded in book one, that came down to a matter of strategy. I had to look at what would be best for readers. Originally, I had all nine characters’ POVs in book one. That…didn’t work.

Dreams of Dust and Steel is an intricate story set in a vast world. I didn’t want to overwhelm people, so I had three questions at the top of each chapter as I wrote book one. Something like this:

1 ) What’s the emotional arc?

2 ) What’s the action in this section?

3 ) What is the world-building/plot introduced?

Every chapter had to have some semblance of all three, or it needed to be cut. This allowed me to make sure there’s always a sense of progress for readers, even when the story slowed down. It also allowed me to ensure characters had continuity in their development, some manner of action occurring regularly–be it dialogue, fighting, etc–and it allowed me to “drip” the world-building to readers in a digestible way.

I want to stay focused on character journeys in this series, while slowly peeling back the world as we go. Novelty is one thing folk love when they read, so this is my way of manufacturing a sense of “newness/freshness” throughout the series.

That keeps the pages turning.

Q] You’re writing two series simultaneously: Dreams of Dust and Steel, as well as a series of novellas set years before the events in DoDaS. Was this always the plan, or had you considered integrating both stories into one series?

MM: This wasn’t a plan until I wrote War Song as a reward to backers in my first Kickstarter. Then, I caught the bug for something dark but slightly more heroic than TPoP.

I’d just read Red Rising as well, and enjoyed Darrow’s story. The way he constantly strategized the next best step, or accomplished incredible feats, alone or with allies, inspired me to write a whole prequel for this legendary character, Danath Ironlight. I realized he shares quite a few qualities with the Reaper and had a similar backstory. In a way, the novella series is an homage to both Red Rising and George Washington.

Q] Comparisons to George RR Martin’s “A Song of Ice and Fire” seem to get tossed around frequently these days, but in this case it feels an apt comparison, with a list of POVs and supporting characters thats ever growing. Is there concern that the story might get away from you, or do you have the full saga planned out in advance?

MM: The full saga is planned out. I know how it ends for all the characters and have book 4 and 5 roughly outlined. Book 3 is done and in revisions.

The advantage GoT has over my series is that all the characters start together. It’s easier to ground into the world, see how characters relate, etc., early on. Easier to lead them into danger and cool scenarios, too, because there’s no worry about bringing them immediately back together.

BUT, all those characters who fan outward from the localized starting point, THEN have to meander back. From a strategic perspective, this can make it hard to wrangle in and may cause a lot of “bloat” through the middle of a story as we have to invent new shit to lead characters toward a conclusion that seems pointless.

Now, the advantage I have over GoT is that all my characters have been moving toward one another from the start. So while I might lose readers early on who dislike the lack of intersection between characters, my way of always narrowing toward something has made each successive book move faster in the writing process, and readers get to be excited as they see their favorite POVS cross paths, or mysteries click into place.

My “bloat” is more toward the front end, but I’d call it necessary character building. At least, no meandering middle bit. Readers who like the series from book one should be in for a treat.

Q] If you have any free time, how do you spend it? Can you recommend any books, games, shows, that have recently caught your interest?

MM: You’re right to ask it the way you did, haha. Not a ton of free time since I have two kids and hustle constantly atm. Fingers are crossed there’s more respite on the horizon, though.

If I had more free time, I’d play a ton of tabletop and board games and have a regular exercise schedule (yoga, martial arts, weightlifting). I’d also do a lot more hiking and paddleboarding. I truly enjoy nature, comedy, TV/movies. Video games are cool, but not my main thing. I love to dance, too.

The top three shows I strongly recommend: Dark, The Wire, Scavenger’s Reign.

Favorite games in recent memory: Ghost of Tsushima and Hogwarts Legacy.

Book review: Slayers of Old by Jim C. Hines

I like the idea of aging heroes forced to save the world one more time. They’ve already done their time in the spotlight, but the world clearly refuses to stay saved for good. Slayers of Old offers a fun take on this trope; it’s cozy, character-driven, and reads well.

Jenny (a hunter once devoted to Artemis), Annette (a half-succubus grandma with sass and scars), and Temple Finn (a nearly century-old wizard bound to his half-sentient ancestral home) have settled into their golden years trying to run a bookstore in Salem. They want peace and to enjoy Temple’s excellent meals. Alas, eldritch horrors don’t have a shred of decency - they don’t care that the former Chosen Ones have arthritis and can barely remember to get dressed.

The house they live in is far more than a backdrop. Thanks to its magical bond with Temple, it creaks and groans with his aches, but it also bends reality. It rearranges its rooms on a whim, creates new ones when needed (say, for unexpected guests), and generally ignores the laws of physics. Between that and the sentient mice who assault neighborhood cats, the setting feels alive in the best way.

The magic here isn’t overly explained, which, honestly, I appreciated. It seeps and lingers and remains unpredictable. The banter between the trio is warm, sharp, and believable. Their friendship comes from decades of shared pain, triumph, and breakfast routines. They’ve all made their mistakes, and lived long enough to understand what matters now.

That said, the coziness comes at a small cost. You know going in that this isn’t the kind of story where the world will end in darkness. There’s comfort in that, sure-but it also meant the stakes never quite reached the heights I like. Evil won’t win, not really. The tone reassures you of that from the start.

And that’s okay. Sometimes I prefer the assurance that the found family will win, that the bookstore won’t burn, and that a haunted van with a ghost mom can be part of the solution. Slayers of Old delivers exactly what it sets out to: heart, humor, action, and magical mischief. Also, the ending isn’t exactly what some may expect, and it’s better for it.

I’d give it 4 stars. Cozy fantasy done right-with some battle scars, strong tea, physics-defying architecture, and maybe a cursed trinket or two.

THE WITCH ROADS by Kate Elliott (Witch Roads #1)

Spotlight on “Typewriter Beach” by Meg Waite Clayton

Typewriter Beach by Meg Waite Clayton is the unforgettable story of an unlikely friendship between…

The post Spotlight on “Typewriter Beach” by Meg Waite Clayton appeared first on LitStack.

Monday Musings: Some Recent Epiphanies

The title speaks for itself. These are recent epiphanies I’ve had. Some are profound others less so. Enjoy.

Last weekend, at ConCarolinas, I was honored with the Polaris Award, which is given each year by the folks at Falstaff Books to a professional who has served the community and industry by mentoring young writers (young career-wise, not necessarily age-wise). I was humbled and deeply grateful. And later, it occurred to me that early in my career, I would probably have preferred a “more prestigious” award that somehow, subjectively, declared my latest novel or story “the best.” Not now. Not with this. I was, essentially, being recognized for being a good person, someone who takes time to help others. What could possibly be better than that?

Last weekend, at ConCarolinas, I was honored with the Polaris Award, which is given each year by the folks at Falstaff Books to a professional who has served the community and industry by mentoring young writers (young career-wise, not necessarily age-wise). I was humbled and deeply grateful. And later, it occurred to me that early in my career, I would probably have preferred a “more prestigious” award that somehow, subjectively, declared my latest novel or story “the best.” Not now. Not with this. I was, essentially, being recognized for being a good person, someone who takes time to help others. What could possibly be better than that?

Nancy and I recently went back to our old home in Tennessee for the wedding of the son of dear, dear friends. Ahead of the weekend, I was feeling a bit uneasy about returning there. By the time we left last fall, we had come to feel a bit alienated from the place, and we were constantly confronting memories of Alex — everywhere we turned, we found reminders of her. But upon arriving there this spring, I recognized that I had control over who and what I saw and did and even recalled. I avoided places that were too steeped in hard memories. I never went near our old house — I didn’t want to see it if it looked exactly the same, and I really didn’t want to see it if the new owners made a ton of changes! But most of all, I took care of myself and thus prevented the anxieties I’d harbored ahead of time from ruining what turned out to be a fun visit. I may suffer from anxiety, but I am not necessarily subject to it. I am, finally, at an advanced age, learning to take care of myself.

Even if I do not make it to “genius” on the Spelling Bee AND solve the Mini AND the Crossword AND Wordle AND Connections AND Strands each day, the world will still continue to turn. Yep. It’s true.

I do not know when or if I will ever write another word of fiction. But when and if I do, it will be because I want to, because I have a story I need to tell, something that I am certain I will love. Which is as it should be.

The lyric is, “She’s got electric boots/A mohair suit/You know I read it in a magazine.” Honest to God.

I am never going to play center field for the Yankees. I am never going to appear on a concert stage with any of my rock ‘n roll heroes. I am never going to be six feet tall. Or anywhere near it. All of this may seem laughably obvious. Honestly, it IS laughably obvious. But the dreams of our childhood and adolescence die hard. And the truth is, even as we age, we never stop feeling like the “ourself” we met when we were young.

Grief is an alloy forged of loss and memory and love. The stronger the love, and the greater the loss, and the more poignant the memories, the more powerful the grief. Loss sucks, but grief is as precious as the rarest metals — as precious as love and memory.

As a student of U.S. History — a holder of a doctorate in the field — I always assumed that our system of government, for all its obvious flaws and blind spots, was durable and strong. I believed that if it could survive the War of 1812 and the natural growing pains of an early republic, if it could emerge alive, despite its wounds, from Civil War and Reconstruction, if it could weather the stains of McCarthyism and Vietnam and Watergate, it could survive anything. I was terribly wrong. As it turns out, our Constitutional Republic is only as secure as the good intentions of its principle actors. Checks and balances, separation of powers, the norms of civil governance — they are completely dependent on the willingness of those engaged in governing to follow historical norms. Elect people who are driven not by patriotism but by greed and vengeance, bigotry and arrogance, unbridled ego and an insatiable hunger for power, and our republic turns out to be as brittle as centuries-old paper, as ephemeral as false promises, as fragile as life itself.

I think the legalization of weed is a good thing. Legal penalties for use and possession were (and, in some states, still are) grossly disproportionate to the crime, and they usually fell/fall most heavily on people of color and those without the financial resources necessary to defend themselves. So, it’s really a very, very good thing. But let’s be honest: Part of the fun of getting high used to be the knowledge that we were doing something forbidden, something that put us on the wrong side of the law. It allowed otherwise well-behaved kids to feel like they (we) were edgy and daring. There’s a small part of me that misses that. Though it’s not enough to make me move back to Tennessee….

I’ll stop there for today. Perhaps I’ll revisit this idea in future posts.

In the meantime, have a great week.

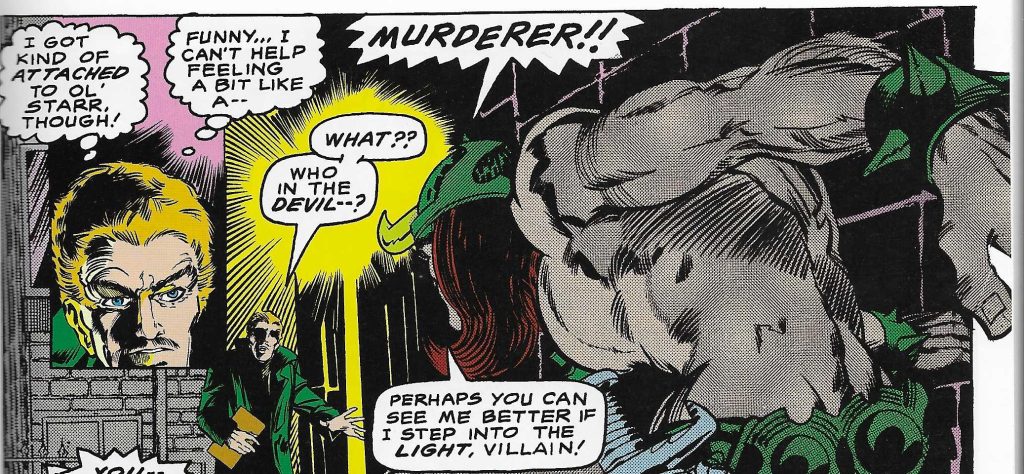

By Crom: It’s Conan…I Mean, Starr the Slayer!

Having finished the first 100 issues of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian, I did a post last week on Roy Thomas’s memoirs and that series. Which OF COURSE you read, here.

Having finished the first 100 issues of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian, I did a post last week on Roy Thomas’s memoirs and that series. Which OF COURSE you read, here.

I started reading the first Savage Sword of Conan Omnibus from Marvel, but I’m still in a CtB mood. So, I decided to write another post about it. Sort of…

The first issue of Conan the Barbarian actually followed the sandalled feet of Starr the Slayer.

Just for fun, Roy Thomas had written a sword and sorcery story, and he had Barry (not yet ‘Windsor’) Smith draw it. Starr the Slayer was a very Conan-esque barbarian. In the story, he was the creation of Len Carson (named after Conan pastiche writer, Lin Carter), who dreamed his plots. But mentally exhausted from this, Carson wanted to kill off his meal ticket. Starr somehow travels to Carson’s time and kills the writer for attempting to dispose of him. Uh, okay, sure.

Starr appeared in the fourth issue of the Marvel anthology, Chamber of Darkness, hitting newsstands in April of 1970 (CtB debuted in October of the same year). Smith both penciled and inked the entire installment for Starr, from Thomas’ story.

Thomas did not intend for it to be an ongoing character, though it seems entirely conceivable that if Marvel had followed form and developed their own in-house character (giving them all the rights), instead of licensing one, Starr could well have been Marvel’s sword-swinger.

Smith gave Starr a distinctive medallion necklace. He also adorned the barbarian with a horned helm – except, the horns were in the front, rather than the side. This turned out to be important, because Smith and Thomas decided to keep both of those items for Conan. Marvel fans were used to superheroes in costumes. Conan got a bit of a mini-costume in this manner.

At only seven pages, it’s pretty short. Smith had been booted out of the United States green-card violations, and drew Starr while in England. He had also been doing some barbarian drawings for his own amateur magazine called Paradox. This black and white drawing by Smith might be one of them.

So, Smith had experience with drawing barbarians when Thomas approached him about Conan. Boss Goodman had put the kibosh on John Buscema by limiting the amount he would pay the illustrator. Which also knocked out fellow candidate Gil Kane (both of who would later draw much Conan). Thomas had passed on a couple Stan Lee suggestions, and then settled on Smith, who was near the bottom end of the pay scale.

So, Smith had experience with drawing barbarians when Thomas approached him about Conan. Boss Goodman had put the kibosh on John Buscema by limiting the amount he would pay the illustrator. Which also knocked out fellow candidate Gil Kane (both of who would later draw much Conan). Thomas had passed on a couple Stan Lee suggestions, and then settled on Smith, who was near the bottom end of the pay scale.

Thus, Marvel rather unintentionally did a trial run at Conan. I talked a bit about how the Conan comic book came about in last week’s post. But I do a deep dive into it in the started but nowhere completed series I have planned here at Black Gate on Thomas’ first ten issues of Conan the Barbarian. I have read the first hundred issues as prep work though. And this essay you’re reading was part of the series.

Marvel could easily have created their own in-house barbarian. And they had offered to pay Lin Carter for the use of his Conan clone, Thongor. But Carter’s agent held out for more money (apparently Martin Goodman NEVER caved on financial matters), and Thomas contacted Glenn Lord, the rights agent for Robert E. H(‘Of Aquilonia’ had come out.oward’s estate.

Lancer was essentially finished printing new Conan books (all but ‘The Buccaneer’ and ‘Of Aquilonia’ had already come out, and there was no popular Conan movie. There was no guarantee that Conan would be a hit. Thanks to those paperbacks with the Frank Frazetta covers, he was more recognizable than Thongor, or John Jakes’ Brak the Barbarian. But Conan was no sure thing as a comic.

Thankfully, Thomas convinced Stan Lee and Martin Goodman, and Conan became not only a Marvel best-seller, but is a popular franchise to this day (Marvel having re-obtained the rights a few years ago, but they are now held by Titan.

Starr did return, though not very memorably.

In 2007, Marvel included a version of Starr in its new version of the newuniversal series. I’ve never seen it, nor am I interested in the concept. You can go look it up for yourself if you want.

In 2009, Marvel’s Max Comics (adult-oriented imprint put out four new Starr the Slayer comics. All four are available digitally.

Prior Conan Comic Posts

By Crom: Marvel, Roy Thomas, and The Barbarian Life

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXVII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

You can definitely ‘experience the Bobness’ at Jason Waltz’s ’24? in 42′ podcast.

Audiobook Review: We Live Here Now by Sarah Pinborough

I received a review copy from the publisher. This does not affect the contents of my review and all opinions are my own.

We Live Here Now by Sarah Pinborough

We Live Here Now by Sarah Pinborough

Mogsy’s Rating (Overall): 4 of 5 stars

Genre: Mystery, Thriller

Series: Stand Alone

Publisher: Macmillan Audio (May 20, 2025)

Length: 8 hrs and 48 mins

Author Information: Website | Twitter

Narrators: Helen Baxendale, Jamie Glover

Sarah Pinborough does it again! We Live Here Now is a gripping blend of domestic suspense and thrills, seasoned with the author’s signature touch of the supernatural. With her knack for unexpected twists and turns, she delivers a fresh take on the classic gothic haunted house tale, even channeling a bit of Edgar Allen Poe.

At the center of this story is a troubled marriage. After Emily is nearly killed in a devastating accident, she and her husband Freddie move from bustling London to the quiet countryside hoping for a chance to start over. But while their new home is on a gorgeous but remote estate called Larkin Lodge featuring charming architecture and idyllic views, Emily still can’t help her feelings of unease. Granted, she’s no longer the same person she was before the accident, which had put her in a coma. The post-sepsis recovery didn’t help either, making her feel depressed about everything she lost, including a pregnancy and her career. Emily’s doctors had even warned her of possible psychological trauma, leaving her wondering if there is something more sinister behind the house’s creaky sounds and drafty halls, or just her frazzled nerves getting the best of her.

And yet, there is a particular room on the third floor that simply feels wrong to Emily, and she doesn’t think it can be explained away by her stress or any medications. She has witnessed strange things happening in this room, and the walls seem to practically speak to her, wanting badly for her to know its secrets. Still, whatever they might be, Emily is certain they can’t be worse than the ones she’s hiding from Freddie—and she’s just as sure he’s hiding some of his own too. As they struggle to settle into their new life, they begin to reach out to friends and neighbors, hoping to restore a sense of normalcy, and perhaps to uncover the terrible truth behind the history of Larkin Lodge.

What really makes this novel tick is its slow-build tension and the way Pinborough creates such an eerie atmosphere. On point with her other suspense thrillers, this story doesn’t try for the big scares, going instead for the gradual creep-under-your-skin strategy. Adding to those tensions are the alternating viewpoints between Emily and Freddie, both of whom are obviously hiding things—from each other and from the reader. Behind every failing marriage, there are two sides of the story, each fraught with guilt, resentment, and mistrust. This results in a tangled narrative that’s full of misdirection, and we’re never quite sure who to believe. The gaps between the characters’ POVs leave just enough room for doubt and second-guessing. What’s the truth? What’s imagined? What else don’t we know?

As for the mystery behind the house itself, I’m definitely not going to be the one to spoil it. Suffice it to say, Pinborough doesn’t rush the reveals. The clues are left to simmer with hints of murder, betrayal, blackmail, and a whole lot of psychological manipulation. It’s all delightfully messy and melodramatic, perfect if you enjoy your thrillers full of unexpected surprises. And if this is your first book by the author, I think you will be floored by the ending. Heck, even long-time fans bracing for the inevitable sucker punch might still be thrown for a loop. I know I was. The finale is a classic Sarah Pinborough jaw-dropper, one of those endings that send you scrambling back to the beginning of the book to see what signs you might have missed.

Finally, I listened to the audiobook, and it was a fantastic experience. Narrators Helen Baxendale and Jamie Glover both bring depth and nuance to their characters, doing a phenomenal job capturing the sense of fraying nerves and growing paranoia. In the end, We Live Here Now is a haunting domestic thriller with a creepy supernatural undercurrent. Highly recommended for readers who enjoy mysteries with a sharp psychological edge and a gothic twist.

![]()

![]()

The Players (by Minette Walters)

Historical Fiction

Thirty-five years after the end of the English Civil War, the Duke of Monmouth (illegitimate son of Charles II) has decided to take the throne for himself. The incompetent and short lived rebellion led to his execution on Tower Hill.

After the capture and execution of the Duke of Monmouth King James II felt particularly angry towards the people of Dorset and set up courts to try and execute the rebels who had sided with the Duke of Monmouth.

After King James ordered the arrest and execution of all the rebels who participated in the rebellion, the Elias Harrier, Duke of Granville sets about saving as many as he can. Through bribes, deception and slight of hand, and with the help of his mother Lady Jayne Harrier and the sharp legal mind of Althea Ettrick they set about saving as many of the young men and women of Dorset who turned of the king as they can.

_____________________________________________________________________________

The Players follows on from The Swift & the Harrier in an entertaining work of historical fiction. The Swift & the Harrierwas set within the events of the English Civil War which makes for a much bigger story. The events in 1685 which underlie The Players were more a flash in the pan than crate of dynamite and in some ways this book feels smaller for it.

Personally I would have enjoyed it more if the author moved away from the history a little and focused on the main characters more, particularly Elias and Althea.

It’s a good book, entertaining, engaging, well written…but it’s hard to hold a book up to The Swift & the Harrier without feeling at least a little disappointed.

Recent comments