Fantasy Books

Women in SF&F Month 2025: Thank You and Links

Thank you so very much to all of this year’s guests for the excellent essays that made April 2025 another amazing Women in SF&F Month! And thank you to everyone who shared their posts and helped spread the word about this year’s series. It is always very much appreciated! This year’s series has ended, but I wanted to make sure there was a way to find all of the guest posts from 2025. This was the fourteenth annual Women in […]

The post Women in SF&F Month 2025: Thank You and Links first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend

Here are 7 Author Shoutouts for this week. Find your favorite author or discover an…

The post 7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend appeared first on LitStack.

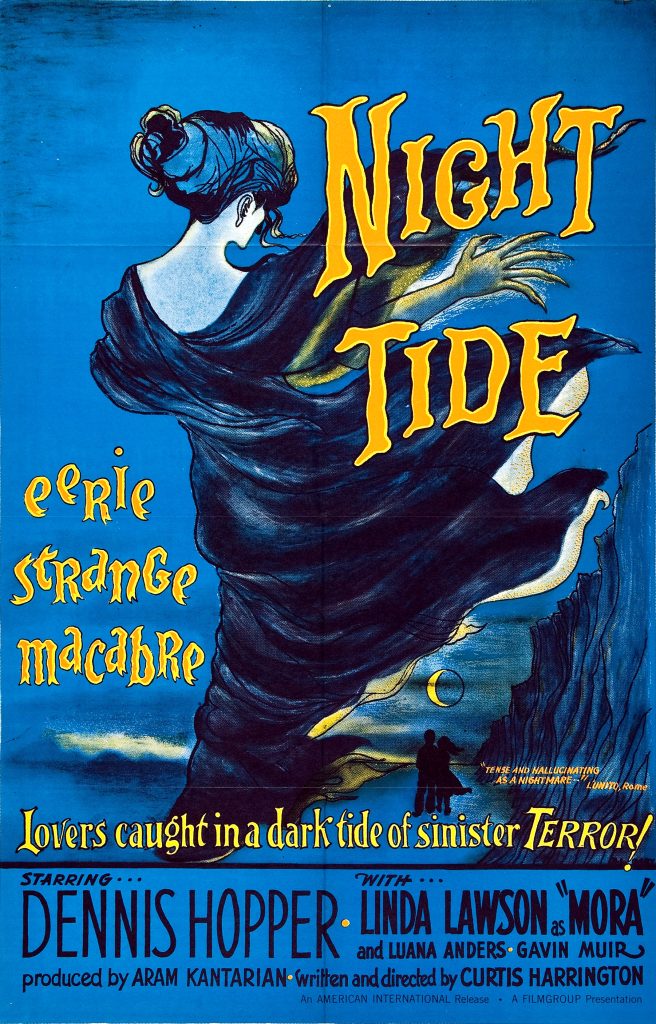

Odd Old Indie: Night Tide

Growing up in Southern California in the 60’s and 70’s was a movie lover’s dream. Late night and weekend television in those days was almost completely given over to old movies, especially on the Los Angeles independent channels: KTLA channel 5, KHJ channel 9, KTTV channel 11, and KCOP channel 13.

The independent stations were especially prone to showing independent movies, small films that hadn’t cost much and hadn’t made much and could be acquired cheaply to occupy all the time that had to be filled until sign-off and the test pattern. Many of these movies were from the House of Corman (The Little Shop of Horrors, The Masque of the Red Death, Dementia 13), but most weren’t, and any night of the week you could watch a pulse-pounder like The Flesh Eaters, The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies, or Beast of Blood (once you had advanced — or descended — to Filipino horror movies you could consider yourself a schlock PHD.)

Most of these films were awful, of course (that’s how you wound up on channel 13 at two in the morning), but sometimes a (relative) diamond could be found among the ashes. One movie that I discovered during those years was Night Tide, an odd little indie that aimed a bit higher than the usual cheapie thriller. I was always happy when it popped up in the week’s TV Guide listings.

Made in 1960 and first screened in 1961, but not widely released until 1963 due to distribution confusion (it has a Corman connection after all, because it was released through Filmgroup, his distribution company) and directed by Curtis Harrington, it’s an offbeat film that has all of the expected deficiencies of a micro-budget independent movie along with some unexpected virtues. (It was supposedly made for $25,000, which wouldn’t even cover George Clooney’s carfare today.)

Clearly taking his inspiration from the series of nine horror films that Val Lewton produced for RKO in the 1940’s (Night Tide owes most to the first of them, 1942’s Cat People), Harrington (who wrote the script as well as directed) tells an ambiguous, poetic, melancholy story in an allusive, indirect way. Making a virtue of poverty, Harrington allows the viewer to fill in everything that is only suggested (because it would cost too much to show it), which was very much the strategy Lewton followed in making his underfinanced gems.

Night Tide is the story of a USN sailor, Johnny Drake (a twenty-five-year-old Dennis Hopper in his first lead role) and Mora (Linda Lawson), a young woman who appears as a mermaid in a boardwalk sideshow. (Most of the movie was shot just west of Los Angeles in Santa Monica.)

Strolling along a beachfront street one night, Johnny drops into a jazz club where he sees Mora sitting alone, raptly listening to the music. Struck by her dark beauty, Johnny asks if he can sit at her table to get a better view of the players. Mora agrees, but brushes aside the sailor’s attempts at conversation. While they are sitting there, a strange, black-clad, intense-looking woman comes up and speaks to Mora in a foreign language. The woman walks away, and Mora, visibly upset, rushes out of the club.

Johnny, desperate to make some kind of connection with this intriguing woman, follows Mora down the darkened street, all the while trying to persuade her to talk with him. Perhaps sensing a loneliness equal to her own and touched by his sincerity, Mora permits Johnny to walk her to her home above a carousel. She rebuffs his request to come upstairs with her, but she permits him to clumsily kiss her goodnight, and leaves him with an invitation to come back in the morning, when she will fix him breakfast.

When Johnny returns the next day, he first takes a look at the merry-go-round under Mora’s apartment, where he meets the ride’s operator and his granddaughter Ellen (Luana Anders), who both respond a little oddly when they hear that he’s there to visit the sideshow mermaid.

When Johnny goes upstairs, Mora greets him warmly and leads him through an apartment decorated with souvenirs of the sea, to a balcony overlooking the ocean, where they will have their breakfast. (Seafood, naturally.) During their conversation, the sailor and the enigmatic young woman shyly begin to get better acquainted.

Mora tells him about her job — “I wear an artificial fishtail and I lie in a tank that looks like it’s filled with water, and people pay twenty-five cents and come and look at me, and that’s how I make my living.” When Johnny asks her if she ever gets tired of it, she wistfully replies, “Sometimes — but it’s restful, anyway.”

When Mora asks Johnny to tell her something about his life, he tells her that he is alone in the world; his father left home when Johnny was just a boy, and when his mother died, he thought that the best way to get away from Denver, Colorado was to join the navy and see the world. “But I haven’t seen any of it yet.”

Then, as they are finishing their meal, an odd thing happens. A scavenging seagull swoops down on the table looking for scraps, and Mora takes it in her arms and gently strokes it and talks to it, and the wild creature seems perfectly calm and content. When Johnny asks her where she learned to do such a thing, Mora says that she doesn’t remember.

After their breakfast is done, they go down to the boardwalk and Johnny meets the man who owns the mermaid attraction and serves as its barker, Captain Samuel Murdock (Gavin Muir). He found Mora when she was a child on the Greek island of Mykonos, and brought the orphaned girl back to the United States as his ward. Murdock tells Johnny to drop by his house sometime; he will tell him some interesting things about his adoptive child.

Soon Johnny is spending every liberty with Mora, and even as they grow closer, the young sailor’s disquiet also grows, as he hears some strange things about his new girlfriend. Ellen (who is clearly attracted to Johnny) and others tell him that two young men who had grown close to Mora drowned in mysterious circumstances; the police are still investigating the deaths.

And one night on the beach, where people have gathered for a party, a curious thing occurs. A musician plays the bongo drums, and Mora begins to dance on the sand; as her movements grow wilder and more ecstatic, she looks toward the ocean and sees, standing silently there, watching her, the black-garbed woman who spoke to her in the jazz club. Johnny sees her too. Mora collapses in a swoon, and when Johnny rushes to her to see if she’s alright he looks around for the woman, but she is gone. The woman vanished n the few seconds it took him to get to Mora.

Increasingly worried, Johnny decides to visit Captain Murdock at his home in cement-canaled Venice, and as he nears the house, he sees the woman again. He pursues her, but she evades him in the maze of canals and bridges. When he arrives at the house, the captain gives him an effusive welcome, but soon adds to Johnny’s unease by telling him that he is in grave danger as long as he continues to see Mora, that the gentle-seeming girl might feel “compelled” to kill him. Before he passes out from drink, Murdock tells the disbelieving sailor that Mora is a siren, a member of the ancient race of sea people who lure men to their doom.

When Johnny tells Mora the captain’s story, she tells him that it’s true — “They are waiting for me to join them.” She believes that the strange woman who is following her is one of the sea people, “here to remind me of the time I must go to them in the sea.” Johnny’s scoffing at this absurd tale can neither shake Mora’s belief in her alien nature and her dark fate, or silence his own growing anxiety.

Visiting Mora after she finishes work one day, Johnny falls asleep on the couch while she takes a shower. He dreams that a towel-wrapped Mora walks out and sits by him on the couch, and looking down, he sees that her legs have turned into a fish’s tail; she is truly a mermaid, a creature not fully human. She leans over and begins to kiss him, and suddenly it is not the arms of a beautiful young woman that enfold him — he is entangled in the grotesque tentacles of a huge octopus, strangling him, devouring him. (This terrifying episode is probably Night Tide’s best-remembered scene.)

When Johnny awakens from this nightmare, he calls out to Mora but receives no answer. She has disappeared. Johnny follows her wet footprints out of the apartment and down to the beach. After frantically searching he finally finds her clinging to the pilings under the pier, barely holding on as she is battered by the waves of the incoming tide. As he carries her back to her apartment, she tells him that the sea people were calling her to them.

The next morning, Mora is strangely calm and later, after telling Johnny that the tides will be perfect (because the moon is full), she urges him to go diving with her at special place that she knows. (A few days earlier Johnny had visited a boardwalk Tarot reader who made ominous hints about his future due to the placement of the Moon card.) Johnny uneasily tries to convince Mora that a dive isn’t a good idea, but, unable to dampen her puzzling enthusiasm, he finally agrees.

Taking out a small boat, they make their dive (after Mora cautions the visibly nervous sailor to stay very close to her), and when they’ve gone down to the deepest point, Mora gets behind Johnny and cuts his air hose. As he desperately fights his way back to the surface, he looks back and sees Mora swimming away into the darkness. After waiting in the boat until long after her air would have run out, Johnny takes the boat to shore and stumbles back to Mora’s apartment, where he falls into an exhausted, troubled sleep.

There he has one last dream of this strange, ill-fated young woman — he sees her as a mermaid, sitting on the rocks with the waves crashing about her, an unreadable expression on her face as she regards herself in a mirror. When Mora turns and sees him, she slips into the churning water. Johnny reaches out and takes her hand, trying to pull her back up onto land, but he is not strong enough to overcome the immense power of the ocean’s pull, and a laughing Mora finally slips away from him and vanishes beneath the surface of the sea.

Later that rainy night, he wakes from this sleep, shaken and desolate, and walks to the boardwalk. Going into the mermaid exhibit, Johnny hesitantly looks into Mora’s tank, where he is stunned to see the body of the drowned girl floating face-up in the water, her hair streaming around her. She is still beautiful, even in death.

Captain Murdock (who found Mora’s body on the beach) emerges from the shadows with a gun in his hand and accuses Johnny of killing her, which the young man denies — “But I loved her.” “You loved her! What do you know about love?” Murdock replies. “I’ve loved her ever since she was a child. You did it and you must pay for it!” Murdock fires at Johnny but misses, and the shots bring the police, who take both men into custody.

At the police station a distraught Murdock makes a confession to a detective (and to Johnny — he asked that the sailor be present). When she was still a child, he began telling Mora that she was one of the sea people in the hope that it would keep her from forming close relationships with anyone else, and so prevent her from ever leaving him. Ultimately, even that didn’t keep Mora from wanting something more, and the captain killed her two boyfriends and made his ward believe that her inhuman nature was somehow responsible for their deaths; he just couldn’t bear the thought of losing the only person in the world he loved, the only person in the world who loved him.

Murdock’s “experiment in psychology” worked only too well; Mora “couldn’t face a recurrence of what had gone before, so rather than destroy the person she loved, she decided to embrace the rapture of the depths.”

The only thing left to clear up is the identity of the mysterious woman — was she an accomplice of Murdock, someone he had paid to follow Mora to remind her of her supposed evil destiny? The broken old man has never seen such a woman, never heard of her. She was part of no plan of his.

When Murdock is led out of the detective’s office, he gently pats Johnny on the shoulder, a sad little gesture between two men who will forever be linked by the loss of the woman they both immoderately loved.

The shore patrol arrives to take Johnny back to his ship, and Ellen is waiting at the desk to express her sympathy and to say goodbye. Maybe on his next liberty, Johnny can come by and take a ride on the carousel? The sailor smiles hesitantly and says that it seems like a good idea. As he walks out of the police station, the rain has ended, and a new day is dawning.

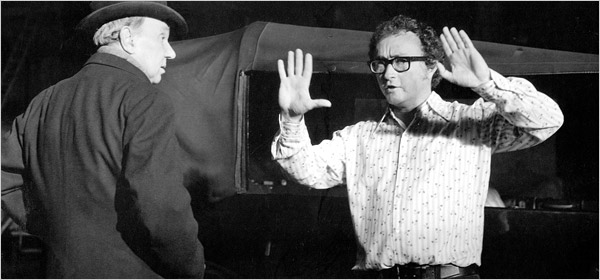

Gavin Muir and Curtis Harrington

Gavin Muir and Curtis Harrington

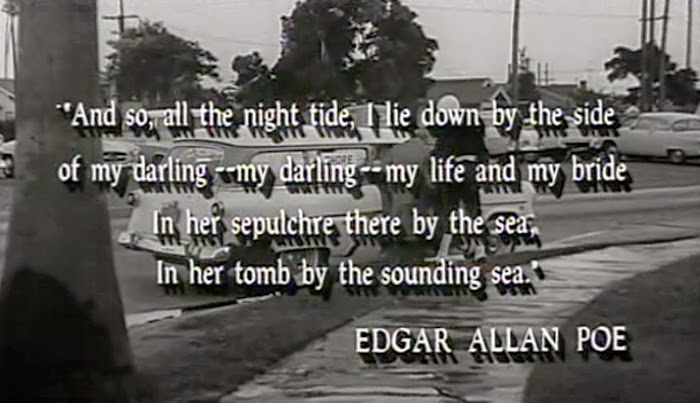

The film closes with the lines from Poe’s “Annabel Lee” that gave it its title: “And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side / Of my darling — my darling — my life and my bride, / In her sepulchre there by the sea — / In her tomb by the surrounding sea.”

So, what do we have here? Is Night Tide a brilliant achievement, a neglected masterpiece? You can judge for yourself (there’s a very nice print on YouTube, though there wasn’t several years ago when I bought my Kino Lorber Blu-ray), but it’s not necessary to go quite that far.

You don’t have to look very hard to find Night Tide’s defects. The story, as I said before (and as Harrington always acknowledged) borrows heavily from Cat People, which is a better, more original film, and even if you’re not familiar with the earlier movie, it’s not too difficult to see where the story is going (Captain Murdock’s big revelation isn’t much of a surprise); the dialogue is sometimes stilted, both in the writing and in the delivery by the actors, some of the supporting playing is erratic, and the mark of the low budget is visually evident in dozens of ways.

But many of these failings have a positive aspect, too. If you’re going to pick a model, Cat People is a strong one, and many of its virtues are evident in its successor, while the low budget compelled Harrington to stick to the commonplace in costumes and sets, giving the movie a much-needed grounding in everyday reality (while also permitting the director to concentrate on character rather than on special effects). Despite a few overtly arty touches, the black-and-white cinematography (much of which was shot at night), strongly conveys the darkness and moody ambiguity of the story. (The film’s flute-heavy jazz score by David Raskin is both a plus and a minus; sometimes it’s delicate, eerie, and just about perfect, while at other times it’s discordantly, distractingly obtrusive.)

Perhaps the film’s greatest assets are Dennis Hopper and Linda Lawson. Both were experienced television actors in 1960, but Night Tide was the first movie lead for both of them, and the awkwardness and uncertainty that are sometimes detectable in their performances actually suit their characters very well. Hopper is convincingly shy and callow (a “fair young man, innocent and searching” as the Tarot reader calls him); his yearning for human contact comes across as touchingly genuine. (At the beginning of the movie, Johnny has some pictures taken in an automated photo booth; he puts his hat on, takes it off, smiles, looks serious… and then tucks the pictures into his pocket and walks away. He has no one to give them to.)

Linda Lawson, despite not being gifted with a very expressive voice, nicely coveys a loneliness and a consciousness of being separated from “normal” people that matches Johnny’s intense desire to connect with someone; she makes the lost, doomed Mora a moving, tragic figure.

Night Tide uses its limited resources to try for something different than the usual rubber-monster-on-the-loose quickie; it’s a mood piece in which feeling and atmosphere are more important than plot, a poetic, offbeat combination of fantasy and horror and mystery, wrapped around an ill-starred, very human love story. In some ways it’s almost an amateur film, but it’s none the worse for that. (Remember that one meaning of amateur is someone who does something just for the love of it.) The movie has a unique flavor, sweet and sad, and for all of its (understandable and forgivable) deficiencies, it lingers in the mind; it gets under your skin.

You can always recognize a film that was truly important to the people who made it, and Night Tide is one of those; clearly, it wasn’t just another job to Curtis Harrington, Dennis Hopper, Linda Lawson, and the rest of the people who worked on it — it meant something to them. If you give it a chance — say late some lonely night — you might find that this old, odd little movie has come to mean something to you, too.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was The Eccentric’s Bookshelf: Michael Weldon’s Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film

The Baby Dragon Café - Book Review by Voodoo Bride

The Baby Dragon Café (The Baby Dragon #1)by A.T. Qureshi

The Baby Dragon Café (The Baby Dragon #1)by A.T. QureshiWhat is it about:When Saphira opened up her café for baby dragons and their humans, she wasn’t expecting it to be so difficult to keep the fires burning. It turns out, young dragons are not the best magical animals to keep in a café, and replacing all that burnt furniture is costing Saphira more than she can afford from selling dragon-roasted coffee.

Aiden is a local gardener, and local heart-throb, more interested in his plants than actually spending time with his disobedient baby dragon. When Aiden walks into Saphira’s café, he has a genius idea – he'll ask Saphira to train his baby dragon, and he'll pay her enough to keep the café afloat.

Saphira’s happy-go-lucky attitude doesn’t seem to do anything but irritate the grumpy-but-gorgeous Aiden, except that everywhere she goes, she finds him there. But can this dragon café owner turn her fortunes around, and maybe find love along the way?

What did Voodoo Bride think of it:This could have been more than it was.

Don't get me wrong:I liked the romance. Once again it was grumpy/sunshine, and I really liked the grumpy Aiden. He's more of an introvert than actually grumpy, I have to say. I totally read this book start to finish to see him get the girl and happiness.

It was the world building and the dragons that didn't vibe for me. I felt like the author didn't really know if the dragons were pets or beings that had similar intelligence as humans. The baby dragons felt really off because of that. I also thought the café wasn't used enough in the story. It was more a starting point than something the book revolved around.

The writing style was nice enough, but didn't draw me in. I was not bored enough to stop reading, and not entertained enough to glue myself to the book.

All in all a nice enough read, but I won't be reading other books in this series/world.

Why should you read it:Grumpy, introverted gardener.

Book Review: When the Wolf Comes Home by Nat Cassidy

I received a review copy from the publisher. This does not affect the contents of my review and all opinions are my own.

When the Wolf Comes Home by Nat Cassidy

When the Wolf Comes Home by Nat Cassidy

Mogsy’s Rating: 4.5 of 5 stars

Genre: Horror

Series: Stand Alone

Publisher: Tor Nightfire (April 22, 2025)

Length: 304 pages

Author Information: Website

I have to admit, the first time I read Nat Cassidy with Nestlings, my feelings were mixed. But boy, am I glad I gave his work another chance, because When the Wolf Comes Home was a trip that went straight for the jugular. It’s horror that masks itself as a traditional werewolf tale, but what you’ll find instead is a raw and emotionally charged story that goes much deeper than that.

Plot-wise, the story follows a young Los Angeles woman named Jessa Bailey who has reached a dead-end in her acting career and is currently trying to make ends meet by working at a dingy diner. After experiencing a traumatic health scare, she makes her way back home feeling anxious and dazed, only to have her night turned upside down a second time when she discovers a terrified little boy hiding in the bushes outside her apartment. After getting him inside and squared away some clothes and food, she gets his story—or most of it, anyway, before they are attacked by a monster. The beast, which looks half man and half wolf, proceeds to tear through the building and kill many of its residents, and Jess and her new charge only barely manage to escape.

It soon becomes clear that the monster is hunting the boy, but that’s not all that’s coming after them. Certain elements in the government are also interested in getting their hands on him, and a Special Agent named Michael Santos has been tasked to track him down on behalf of a secret organization. Jess has no idea why so many people are desperate to find the boy, but the longer she spends with him, the more she realizes he’s special. Strange and uncanny things seem to happen around him, which Jess finds disturbing and hard to believe. However, once she is named as a person of interest in the attack on her apartment, their fates become intertwined. With no one else to turn to, Jess becomes the boy’s protector and his only chance of survival.

When the Wolf Comes Home is the kind of novel that would translate well to the big screen, with cinematic writing that moves at a fast clip and a story with plenty of action and just the right amount of emotional resonance. But while a film adaptation of this book would undoubtedly be a horror movie, simply because of all the gore and terror, I also think it would be a lot more complicated. As the plot progresses, the surface peels back to reveal several layers of meaning. Our protagonist Jess is deeply flawed and unsure of herself, still feeling raw from the pain of losing her estranged father whom she’s never forgiven for abandoning her. The story’s themes hit hard when you realize the monster chasing her is more than a creature of folklore.

There’s also a surreal quality here that I wasn’t sure what to make of, initially. There were certainly scenes that bordered on sheer absurdity, and I confess, when the first of these scenes hit, my regard for the novel dropped considerably. But this was before I realized how integral these moments were to the big picture. Without spoiling anything, these distortions to reality are directly related to the mystery surrounding the boy and the ideas underpinning the entire story. I couldn’t possibly hold the surrealism against the book after that and even started to enjoy these moments when they added a spot of humor to an otherwise bleak premise.

And truly, most of this book is dark. Sometimes it gets too dark, and you wonder how much more our characters can afford to lose and still manage to keep their hope and sanity. There’s a heaviness that borders on exhausting, and so perhaps it is not surprising that my main complaint lies in the ending. At times, when I’m feeling generous, I think to myself that there’s no other way things could have played out. But when I’m in a more critical mood, I feel like the pacing was all wrong. If nothing else, the novel probably should have ended soon after the climax and not have such a long denouement.

Still, When the Wolf Comes Home is a fantastic read, and a standout in horror fiction. In fact, it easily ranks as one of the most memorable horror novels I’ve read in recent years. When you pick up the book, look at its cover and read its title, you’d be forgiven for thinking this is just another werewolf story. I know that’s what I thought at first. But instead, what Nat Cassidy has delivered here is entirely his own: a wild and weird blend of tension, chills, and heartbreak. It simply works.

![]()

![]()

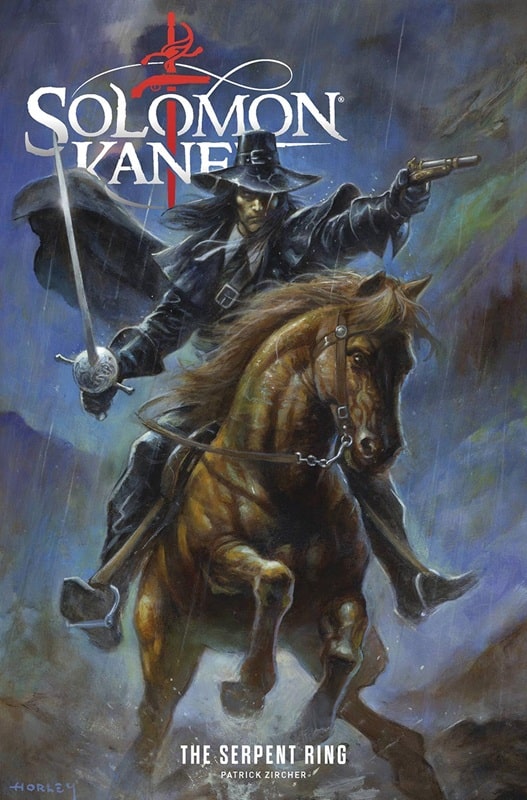

Swordfights, Mysteries, and Dark Sorcery: Solomon Kane: The Serpent Ring #1 by Patrick Zircher

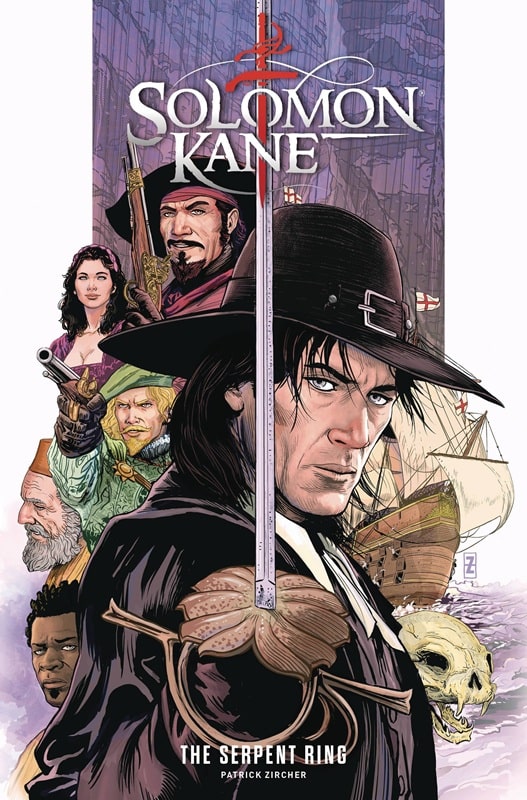

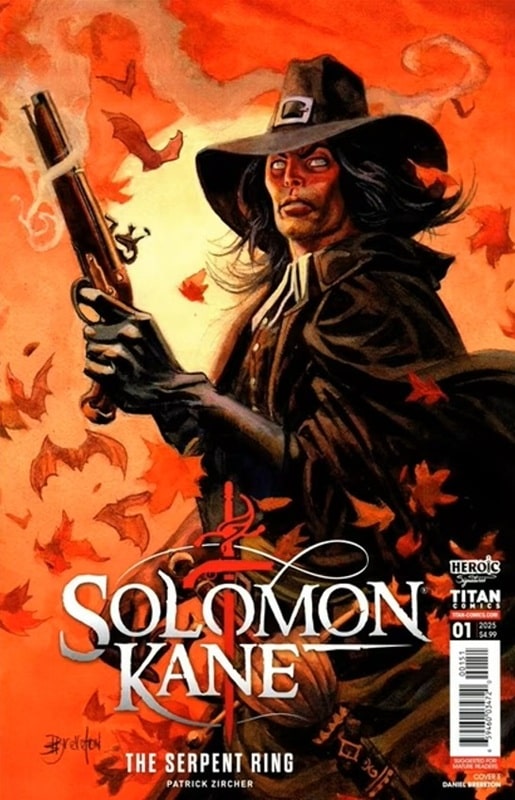

Solomon Kane: The Serpent Ring #1, and variant cover by Daniel Brereton (Titan Comics, March 26, 2025)

Sometimes a project and a creator are brought together in the right place at the right time. Titan Comics’ Solomon Kane mini series The Serpent Ring is one of those times. Writer/Artist Patrick Zircher is working at the very top of his game. The project is dear to his heart, and it shows.

The first issue begins, fittingly enough, in Africa. This would have pleased Kane’s creator Robert E. Howard, because some of REH’s best Kane tales, “The Footfalls Within,” “The Hills of the Dead,” “Wings in the Night,” etc, take place on that continent.

[Click the images to ring in bigger versions.]

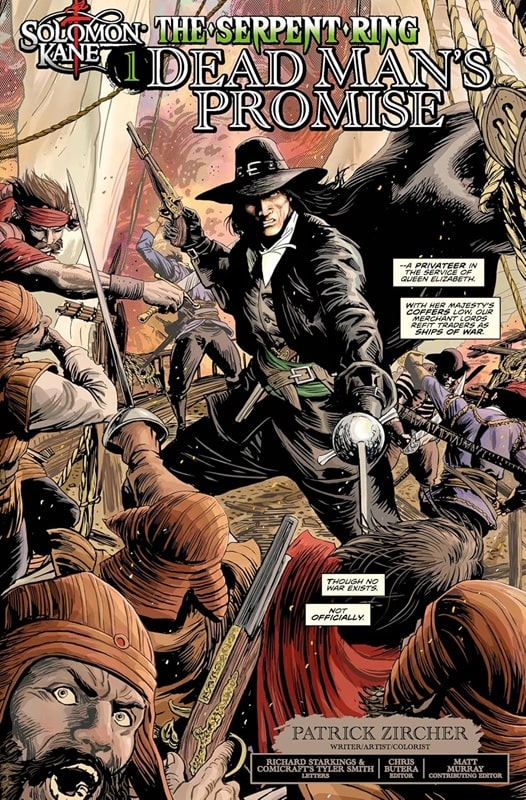

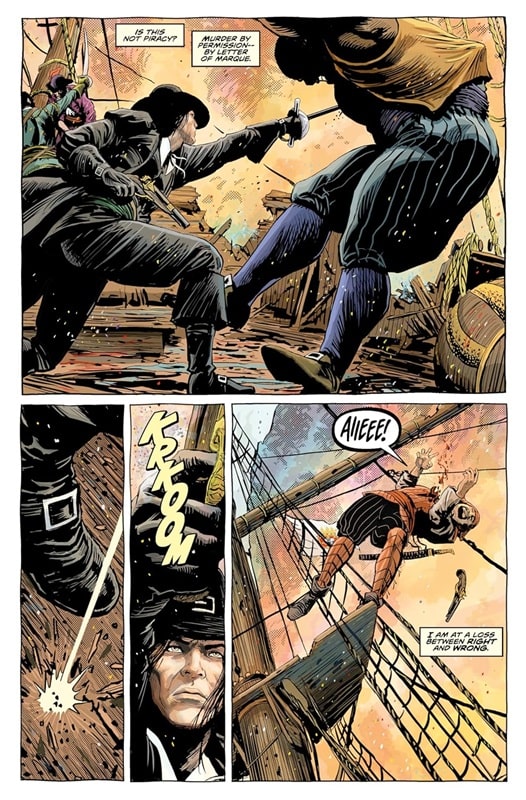

Interior art for Solomon Kane: The Serpent Ring #1 by Patrick Zircher

The first few pages of the comic are a prologue introducing some mysterious characters and incidents. We pick up with Solomon Kane three pages later, serving with a band of Queen Elizabeth’s privateers. Kane and his companions are in a pitched battle with the crew of a Spanish ship.

In an unfortunate occurrence Kane kills a passenger, ‘an innocent man,’ and makes a promise to the dying man to atone for his mistake. This sets the main plot in motion and Kane’s quest will take him from the Barbary Coast to Italy. On the way there will be swordfights, pistol battles, mysteries added to mysteries, and intimations of dark sorcery.

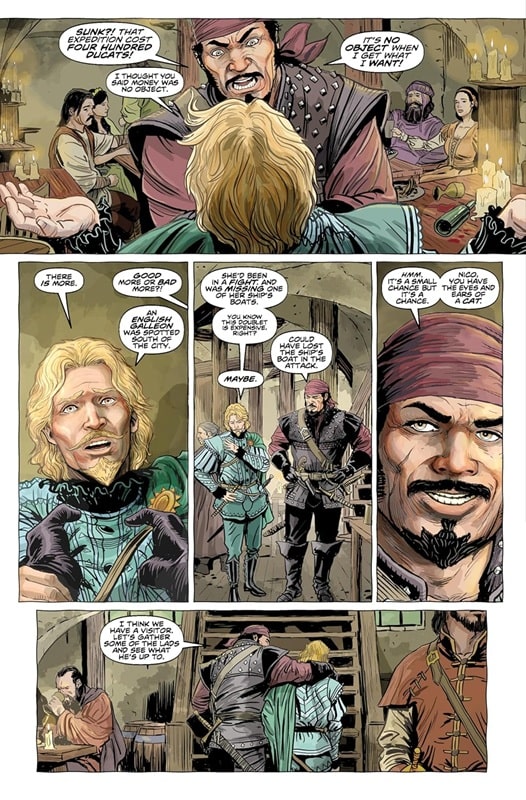

More interior art for Solomon Kane: The Serpent Ring #1 by Patrick Zircher

That’s all the plot I’ll give away, because you should read it for yourself, so let me talk a bit instead about Patrick Zircher’s work on the comic. Having spoken to Patrick online a good bit, I know this is one of his favorite comics he’s ever worked on. He’s a huge fan of Solomon Kane and it really comes through on the pages.

The story has an epic feel as it ranges around Europe, and a large cast of characters. All of that is well researched and beautifully illustrated, be it sailing ships or the streets of Napoli and Venice. Period costumes, weapons, and people are all extremely well done.

Issues #2 and #3 of Solomon Kane: The Serpent Ring. Covers by Rafael Kayanan and Alex Horley

For the Robert E. Howard fan this is prime stuff, Solomon Kane drawn and written by someone who loves the character and the world. It’s very much in the spirit of Howard’s work. I asked Patrick for a quote about his feelings working on the book and he said:

Solomon Kane embodies, in one character, what I love in stories. Action, adventure, suspense, horror, heroism, and wrestling with the ‘big questions’ of life.

Can’t ask for more than that.

Charles R. Rutledge lives in Atlanta, Georgia. This is his first article for Black Gate.

Women in SF&F Month: International Giveaway

I’m giving away one book of the winner’s choice for Women in SF&F Month today! Since there were some US-only giveaways earlier this month, this giveaway is for everyone else (though there are a few caveats given international shipping). Here’s how it works: You can choose your own adventure from the books/authors featured this month available on Kennys Bookshop, and I will ship the winner the book of their choice. This giveaway is open to anyone on the list of […]

The post Women in SF&F Month: International Giveaway first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Teaser Tuesdays - A World Alone

Zombies! Very excited about diving into this one.

THERE'S ONE IN THE HOUSE. The dragging thump of footsteps, somewhere downstairs, is what tips me off.

THERE'S ONE IN THE HOUSE. The dragging thump of footsteps, somewhere downstairs, is what tips me off.(page 1, A World Alone by R.K. Weir)

---------

Teaser Tuesdays is a weekly bookish meme, previously hosted by MizB of Should Be Reading. Anyone can play along! Just do the following: - Grab your current read - Open to a random page - Share two (2) “teaser” sentences from somewhere on that page BE CAREFUL NOT TO INCLUDE SPOILERS! (make sure that what you share doesn’t give too much away! You don’t want to ruin the book for others!) - Share the title & author, too, so that other TT participants can add the book to their TBR Lists if they like your teasers!

GUEST POST: What Fantasy Monsters Reveal about Our Deepest Fears by Caroline R.

(Hyperion Japanese cover art)

(Hyperion Japanese cover art)Despite the genre’s escapist premise, fantasy literature often hosts cutting commentary on real-world issues. The monsters that terrorize these tales—from mythical beasts like the Kraken to the eerie walkers of today’s The Walking Dead—can symbolize humanity’s deepest fears and our most naked vulnerabilities. Through these creatures, fantasy stories have always held a mirror to the shifting anxieties of their eras. As an avid fantasy reader who worries constantly about our collective future, I’m interested in how fantasy monsters represent universal alarm—and how the stories that harbor these monsters continue to fulfill our ever-increasing need for escapist media.

The earliest mythical monsters in human history stemmed from the need to explain mysterious natural phenomena. The creatures of ancient myths often embody our most basic, physical fears: the violence other species, the destruction wrought by severe weather, humanity’s defenselessness against unthinking and uncontrollable natural forces. In ancient Greece, for instance, all meteorological occurrences—from prosperous harvests to devastating floods—were thought to be the direct result of godly intervention. The Greek gods were alternately merciless monsters and generous benefactors; they both caused and exacerbated humans’ powerlessness.

Some of the beings that populated classical myths were more straightforwardly monstrous, and these too represented fears inherent to human existence: the Minotaur, trapped in a labyrinth alone, represents the violent parts of human nature that emerge with isolation. The serpent-like hydra, with its multiple heads, could be said to embody chaos—the uncontrollable force of natural disasters, perhaps, or the seeming inevitability of war.

Many of these monsters can also be linked to moral and religious narratives. The Minotaur’s defeat by the hero Theseus could be said to symbolize the triumph of virtue over vice, a theme that appeared in ancient mythology and remains popular in fantasy literature today. The hydra, which is often associated with Ares, the god of war, sometimes represented punishment for moral failings, reminding us that ignoring religious or ethical obligations could trigger disastrous punishments. Thus, these early myths used monsters not only to explain the natural world, but also to prop up a moral framework.

(THESEUS AND THE MINOTAUR by Barret Chapman)

(THESEUS AND THE MINOTAUR by Barret Chapman)As exploration and colonialism brought unfamiliar cultures into contact with each other for the first time, new fantasy monsters emerged to account for explorers’ fear of the unknown. Fantasy monsters developed during this era often symbolized the threats posed by unfamiliar territories, cultures, and species, embodying anxieties about difference. The Kraken of Nordic folklore offers an excellent example. A colossal, squid-like creature, the Kraken could pull down ships with its powerful tentacles. For European sailors during the Age of Exploration, the mythological Kraken symbolized the very real danger of the open sea.

Other fabled monsters were developed during this era to represent the indigenous peoples of colonized lands Ogres, cannibalistic giants, and other “savage” human-like creatures populated stories like The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a fictional 14th-century travelogue that describes various monstrous beings believed to inhibit the New World. These "monstrous races”, which include “dog-headed Cynocephales” and “one-legged Sciapods”, mirrored appearance-based prejudices against native peoples.

Unlike the religious mythology of classical societies, stories that emerged during this era were more explicitly fictional. The fictional form gave writers license to exaggerate stereotypes that portrayed indigenous people as grotesque barbarians, reinforcing the fear and misunderstanding that often accompanied encounters between European explorers and native populations. This fear was not only of physical harm, but also of contamination wrought by cultural difference. Narratives of the time often portrayed European explorers or settlers as the heroic figures who, by defeating these monsters, demonstrated the superiority of their culture and values.

As we’ve seen, the development of fantastical monsters has always been rooted in real fears. This continues today, with fantastical monsters in literature reflecting the complex existential woes of modern people. As technology has advanced, social structures and global concerns have shifted, and so too have the monsters that embody these concerns. Now, many fantasy monsters represent common fears of environmental degradation, political collapse, and social injustice.

One compelling example of this is Blood Over Bright Haven by M.L. Wang. The story’s villain—who I won’t reveal, since you should read the book yourself—causes the protagonist to wonder whether she can trust anyone. The villain’s conniving manipulation, and the unjust magical system of the setting, both parallel modern distrust in authority and misuse of power.

In many modern fantasy narratives, the villains represent worst-case scenarios that humanity dreads: unchecked corruption (represented by the Darkling from Shadow and Bone), fear of being forgotten (represented by the veil in The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue) and the devastation wrought by modern warfare (represented by the tyrants in The Poppy War). These creatures mirror real-world fears and anxieties, but the narratives where they appear often provide a kind of hope—usually, despite the worst, the protagonists of these stories emerge victorious and some form of justice is served.

Those happy endings are what allow modern fantasy to maintain its escapist allure, even when it contains allusions to very real social ills. Generally, fantasy books and series end with something of a happy conclusion: the protagonist tends to vanquish the monster; the world tends to return to some semblance of order; the villains tend to end up dead or exiled. In a world where these just endings are so rare, reading fantasy allows us to indulge in satisfying depictions of the justice we don’t see in real life.

Thus, fantasy’s use of realistic monsters does not betray its escapist properties, but bolsters them. It wouldn’t be interesting to read about a world in which everything is perfect all the time, but it can be exciting and validating to read about a world in which grit and determination can lead to meaningful social change.

The journey from ancient myth to modern fantasy reflects a shift in our relationship to reality. In early mythologies, monsters were believed to be real, physical embodiment of the unknown and unexplainable forces of nature. They were creatures to be respected and feared, forcing humans to recognize the limits of their knowledge and physical ability. As our understanding of the world expanded, these monsters were gradually relegated to the realm of fiction, appearing in explicitly fictional narratives that allowed us to confront our fears from a safer distance. While most people no longer believe in dragons or sea monster, their symbolic power hasn’t been diminished.

The monsters that populate fantasy literature have always been imaginative and otherworldly, but their significance goes far beyond simple escapism or entertainment. Through these creatures, and the characters’ reactions to their violence, fantasy can often elucidate something insightful about the real world. From the ancient monsters that represented natural threats to the modern creatures that reflect existential dread, fantastical villains can all teach us something about the most profound aspect of the human condition. They give voice to the darkness within and without, reflecting both evolving external threats and timeless internal struggles.

But, despite the terrifying nature of these creatures, the genre itself remains fundamentally optimistic, offering visions of triumph against every kind of evil. While the real world often feals messy and unjust, these stories offer a reassuring sense of order. Many of us feel powerless to confront the monsters we encounter every day—the dangers of unchecked authority, the collapse of social systems, and the degradation of the environment, to name a few—but fantasy provides a safe space to confront these fears.

At their core, fantasy monsters aren’t just symbols of our fears—they’re also reflections of the human condition. They show us the darkness we often try to ignore, but also offer hope that, despite our vulnerabilities and flaws, we can overcome existential challenges. By confronting these monsters in stories led by fearless protagonists, we learn more about our own fears—and how we can rise above them.

Author bio: Caroline is a writer for Reedsy and NowNovel who covers everything from the nitty-gritty of the writing process to the business of finding ghostwriting jobs. When she isn’t writing, Caroline loves reading indie books and spending time outdoors.

Book review: When the Moon Hits Your Eye by John Scalzi

Book links:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Publisher: Length: Formats:

The moon turns into cheese. Not metaphorically. Not in a dream. Like, literally. One day it’s the regular rock-ball we all know and ignore, and the next, it’s dairy. That’s the book. That’s the premise. I rolled my eyes too. But then I started reading, and - well, I ended up liking it more than I thought I would. More than I probably should’ve, honestly.

This is John Scalzi doing what he does best - taking a totally absurd idea and running with it. The moon becomes cheese (type undetermined). People react. Some panic, some scheme, some try to monetize it, some go to church. And through it all, Scalzi’s trademark mix of snark, satire, and sneaky emotional depth holds the whole gooey mess together.

There’s not really a central protagonist here-unless you count humanity in general, or maybe capitalism. Instead, we bounce around between a rotating cast of scientists, astronauts, cheese mongers, billionaire tech bros, diner regulars, and one very cursed Saturday Night Live episode. It's like a disaster movie crossed with a sociology paper, but funnier and with more dairy puns.

The plot meander a a bit and I admit I did I lose track of a few characters. But the short chapters kept things moving, and there’s something irresistible about how this book doesn’t try to be anything other than what it is: a ridiculous thought experiment with a surprising amount of insights into human behavior.

If you’ve read Kaiju Preservation Society or Starter Villain and enjoyed the vibes, you’ll probably enjoy this one too. If you haven’t, but the idea of “slice-of-life apocalypse, but make it cheese” sounds appealing, you might be in for a good time. Just don’t come in expecting hard sci-fi. This is soft cheese fiction. And that’s kind of the point.

THE GHOST WOODS by C.J. Cooke

Book Review: The Ghost Woods by C.J. Cooke

I received a review copy from the publisher. This does not affect the contents of my review and all opinions are my own.

Mogsy’s Rating: 4 of 5 stars

Genre: Historical Fiction, Horror

Series: Stand Alone

Publisher: Berkley (April 29, 2025)

Length: 384 pages

Author Information: Website

This is the fifth book I’ve read by C.J. Cooke, and I think her writing and storytelling just keep getting better and better. The Ghost Woods has quickly become one of my new favorites by the author, second only to A Haunting in the Arctic. Once more, readers are transported to a historical setting where the atmosphere is thick with tension and mystery—with just a touch of the supernatural—and the emotional depth of the characters takes center stage.

In The Ghost Woods, Cooke returns to Scotland’s misty and isolated countryside to spin a tale exploring themes of motherhood and life altering decisions. Set in 1959 and in 1965, the novel follows two women who finds themselves at Lichen Hall, a home for unwed pregnant girls. Mabel is first to arrive in the earlier timeline, frightened and confused because she has no idea how she got pregnant, and no one believes her even though she swears she has never been with a man. Several years later, Pearl makes the same journey to the old mansion in preparation for the birth of her baby, the result of a careless one-night stand following a split from her long-term boyfriend. After losing her nursing job because of it, Pearl’s family thought it would be best for her to lay low until she gives birth.

While Mabel and Pearl come from very different backgrounds, both women come to similar conclusions about Lichen Hall. It is a strange and eerie place, hidden in the woods far from the nearest town and hospital. Many parts of the house are in disrepair, with mold permeating the walls. The property belongs to the Whitlock family, but it is Mrs. Whitlock who clearly runs the show, as old Mr. Whitlock is ill and mostly bedridden, kept out of sight. Also living with them is their grandson, a trouble young man who makes some of the girls staying at the home uncomfortable. As hosts, the Whitlocks are cagey and seemingly hiding some secret knowledge about their huge crumbling mansion, in which Mable, Pearl, and the other women shut away there find themselves trapped.

Like all of Cooke’s other novels, The Ghost Woods excels in atmosphere. Lichen Hall is a character unto itself—distinct with its own unique personality, and that personality to malevolent and threatening. The women, already feeling alone and vulnerable because of their conditions, are made even more anxious knowing Mrs. Whitlock does not believe in outside help. The lady of the house is a mysterious character, kind and comforting one moment, cold and cruel the next. Whatever her motives though, she is adamant that no doctor will ever be called, so the young expectant mothers can only rely on each other. This gives the story a claustrophobic and oppressive vibe, where among the vivid descriptions of the encroaching forest, nothing feels entirely safe.

The plot also employs dual timelines, which I felt was mostly effective. Being relatively close in time, however, sometimes the two threads blurred, especially once Mabel and Pearl’s perspectives came together and intertwined later in the book. The slow build at the beginning also made those early chapter the most challenging, but pacing improves once the story introduces more characters and gives the chance for the horrors at Lichen Hall to develop.

There’s also the slight issue of too many things happening at once, to the point where I feel some of the more minor story threads were not satisfactorily resolved. However, the answer to the most important mystery as well as the twist at the end of the book helped make up for it and made me more forgiving of any loose ends. In fact, the abundance of ideas and themes added overall to the novel’s rich layered feel, even if I would have welcomed a bit more tightening.

All in all, C.J. Cooke delivers another chilling and atmospheric tale in The Ghost Woods, and I think both fans of her previous work as well as new readers will find plenty to love here. This is gothic horror at its finest. Also highly recommended if you enjoy broody historical fiction with a touch of the fantastical, such as influence from fairytales and folklore, or simply unearthly ways of looking at the natural world.

![]()

![]()

Women in SF&F Month: Kate Elliott

Today’s Women in SF&F Month guest is Kate Elliott! Her work includes the epic fantasy series Crossroads, the space opera series The Sun Chronicles, and the young adult fantasy series Court of Fives, to name a few of her many books. Her next novel, The Witch Roads, is described as the “fantastic first in a new duology…filled with rich worldbuilding, political intrigue, and themes of class and family secrets” in a starred review on Library Journal. Her newest book will […]

The post Women in SF&F Month: Kate Elliott first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Monday Musings: Nesting (Redux) and Writing

Back in early January, with snow falling on our bare trees and the brisk cold of a northeastern winter defining our days, I wrote a post for this blog about “Nesting.” The title referred to what Nancy and I had been doing around the house — unpacking, finding places for our stuff, making improvements to the new house.

That process has continued in the months since. While we have also done other stuff — editing, music, birding, and other pursuits on my part; weaving, knitting, and getting her last academic paper published on Nancy’s part — we (mostly Nancy) have still been working on the house. My hands are not (and never have been) steady enough to paint the trim around the interior of the house, so Nancy has carried the bulk of that burden. And with the onset of spring, my multi-talented spouse has also been planning her approach to landscaping our new yard. And I have done more unpacking and have been slowly hanging our art around the house.

I posted a couple of photos of the new place back in January, but wanted to follow up with a few more today.

And I wanted to say a few things about this blog, which I seem to be struggling to keep up with consistently. I am trying. Truly. A lot of the time, though, I just don’t want to write. It really is as simple as that. Most days, I wake up, confront the newest atrocity committed by this hateful, cruel, criminally incompetent Administration, and am torn between wanting to write yet another outraged screed and wanting to ignore politics altogether. I don’t want this blog to become nothing more than a nonstop critique of all the current occupant of the White House is doing to undermine the strength of our republic. But I also don’t want to post about birds or baseball or our latest favorite series on Netflix when the country is burning down. And so I go for weeks without posting at all, which isn’t an answer either.

This is actually symptomatic of a larger problem. I’m not writing much of anything — not blog posts, and not fiction. I did some fiction writing early last year, when I was hired to write something in someone else’s world. But the truth is, I haven’t written a word of fiction that was really my own since we lost Alex back in October 2023. Will I write again? I hope so. That’s all I can say for certain. I want to write again. But I don’t want to write now, and I feel that I owe it to myself to take this time to continue healing. I have no idea how long this feeling will last. A month? A year? A decade? Maybe. Maybe. Maybe. All I know is, I need to take care of myself.

Because I AM healing. I’m doing better in most ways than I was a year ago, and far better than I was a year and half ago, when the grief was fresh and I thought it would never ease.

Watching the house come together has been good for me. Watching spring touch our little slice of the Hudson Valley has been lovely. Trees are blooming. Flowerbeds are revealing themselves. We moved in late in November, so the arrival of warmer weather has been a revelation for us.

I saw Erin in March. I will see her again in May. And then June. And then maybe later in the summer. And then . . . soon after that. Being with her is a balm for both Nancy and me. And so is Nancy and my time together. The love tying our family together remains strong, and in many ways missing Alex, loving her, grieving her, has become one more unbreakable filament binding us to one another.

So we nest. We heal. We love. And we continue to ask your patience and support.

Have a wonderful week.

Spotlight on “The Emperor of Gladness” by Ocean Vuong

Ocean Vuong returns with The Emperor of Gladness, a novel about chosen family, unexpected friendship,…

The post Spotlight on “The Emperor of Gladness” by Ocean Vuong appeared first on LitStack.

What I’ve Been Reading: April 2025

I continue to listen to audiobooks daily. They fit my lifestyle and let me get to a lot more stuff than I would if I just read. I mean, driving with a paperback in hand is quite the challenge!

I continue to listen to audiobooks daily. They fit my lifestyle and let me get to a lot more stuff than I would if I just read. I mean, driving with a paperback in hand is quite the challenge!

I just re-listened to the entire SPQR mystery series by John Maddox Roberts (who I have written about several times, including here). No way I could have sat down and re-read all thirteen.

And I plodded through listening to all 44 hours of Toll of the Hounds, the eighth book of Steven Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen. It was the first book in the series I didn’t really care for – possibly because I don’t like the narrator. But I’ve had a paperback copy on the shelves for ten years, I think. At least I worked in listening to it. I have the audiobook for Dust of Dreams, which is just as long. But the same guy read the whole series, and I don’t want another 40+ hours of him.

But, I do like to still read a physical copy. So, let’s get to what I’ve been checking out on the printed page.

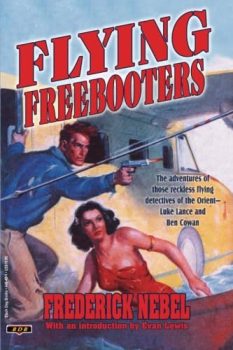

FLYING FREEBOOTERS – Frederick Nebel

Nebel’s is the second face on my Hardboiled Mt. Rushmore (Hammett on one side, Norbert Davis on the other). I’m not into the Aviation Pulps, but I am a fan of Nebel’s Gales & McGill action stories. I added several of Nebel’s Pulp Collections from the Black Dog Books table at Windy City. This included some of his other aviation stories. And I’m becoming more of a fan. Flying Freebooters contains three stories. “Isle of Lost Wings” and “Flying Freebooters first appeared in Wings magazine, in 1930.

Nebel used two organizations for many of his aviation stories. Garrison Airways is a flying service (passengers, mail, and freight) in the Far East. Feisty little Sam Garrison is founder and boss, with hardboiled pilots working for him. I’ve read a couple Garrison stories.

The second, the Strait Agency, is essentially a combination aviation security and private police force, also operating in the Far East. The use of airplanes in these reminds me of Horace McCoy’s Air Texas Rangers stories.

The first story is third person, while the second (and also the third in the book, are first person). These are high action, hardboiled stories that fly along, page after page. Nebel was writing for Black Mask at at this time as well, but he had developed, and continued honing, his craft in the Aviation Pulps. I am enjoying these, and I look forward to the other books I picked up, including some of his Canadian adventures.

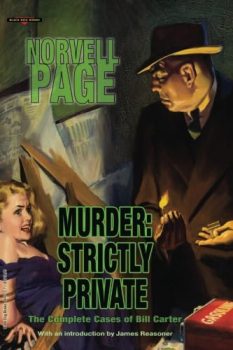

MURDER: STRICTLY PRIVATE – Norvell Page

Version 1.0.0

Version 1.0.0

Page is best known as the primary writer of the hero Pulp, The Spider (under the house name, Grant Stockbridge). Like most Pulpsters, he wrote many genres, including weird menace, and G-men stories. I have his limited Western output as a Black Dog e-book.

I really struggle with the Spicy Pulps. Briefly a popular genre, they’re just so goofy I can’t take them seriously enough to enjoy them. I wrote a post on a Robert E. Howard spicy story – and it was more of a saucy-tinged adventure. Whereas, I can’t even finish a Dan Turner (Hollywood Detective) story in one -sitting.

Robert Leslie Bellem’s Turner is the most popular of the spicy detectives, even getting his own magazine. But to me, it’s like a parody of Race Williams. And Williams can be hard enough to absorb, without making it a spicy parody.

Page wrote a series of spicy stories featuring Bill Carter (who is not his Weird Menace star, Ken Carter), an investigative reporter in Miami. This volume collects (all?) twenty of them. Page is still kinda over-the-top for me, but these are FAR more readable than the Dan Turner stories. I’ll work my way through this book.

Speaking of Page, I recently picked up his short novel, Flame Winds, which originally appeared in the June, 1939 issue of Unknown magazine. It’s his take on the Prester John myth. Lamb included the Prester John legend in the Khlit story I’m currently reading now, “Changa-Nor.”

Roy Thomas used the novella for a three-part Conan comic, “Flame Winds of Lost Khitai.” I got the book because I plan on doing a Black Gate post on the whole Flame Winds thing. Should be neat, and I can incorporate the Lamb story as well.

WOLFE OF THE STEPPES – Harold Lamb

Lamb was a prolific Pulpster in the early 20th Century. A historian as well, his adventure stories are detail-filled thrill-rides. There are eighteen tales of Khlit the Cossack, a gray-bearded survivor on the Asian steppes around the start of the 17th Century.

Lamb was a great influence on Robert E. Howard, and Howard Andrew Jones collected all the Khlit stories in four volumes. There are four more books of Lamb’s adventure tales as well. The first story, which was much shorter than the others, didn’t do anything for me. The next three were novella length, and better Then I hit two linked stories: “The Mighty Manslayer” and “The White Khan.” I’m definitely into these tales now. I am reading the next, and I am enjoying Khlit.

Other than REH, I don’t read Adventure stories, but Lamb was good. I’ve read a couple of his Viking, and Crusader, stories, from other books. They were also good reads.

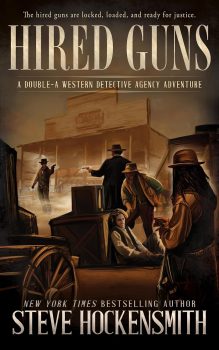

HIRED GUNS – Steve Hockensmith

In February of 2024, I read/listened to the entire Holmes on the Range series, then I did a new post, a comprehensive chronology, and then a Q&A with Steve. I’m a HUGE fan of these fun Western mysteries, with a Holmes influence. Link to all three posts, here.

In February of 2024, I read/listened to the entire Holmes on the Range series, then I did a new post, a comprehensive chronology, and then a Q&A with Steve. I’m a HUGE fan of these fun Western mysteries, with a Holmes influence. Link to all three posts, here.

Later in 2024, he published two new Hired Guns, and No Hallowed Ground, featuring other operatives of the Double-A Western Detective Agency. I read the first book, and I liked it. These are Western mysteries – no Holmes influence. More like hardboiled cowboy stories. Looking forward to the second one when I can fit it in the schedule. I really enjoy reading Steve’s stuff.

Other What I’ve Been ReadingWhat I’ve Been Reading: November, 2024: (Glen Cook, Dodgers’ baseball)

What I’ve Been Reading: September, 2024 (Harold Lamb, Hugh Ashton, Scott Oden)

What I’ve Been Reading: November, 2023 (Holmes on the Range, The Caine Mutiny, Jules De Granden)

What I’ve Been Reading: September 2022 (Columbo, Douglas Adams, Cleveland Torso Murderer)

What I’ve Been Reading: May, 2021 (Cole & Hitch, Dortmunder, and Parker, and Tony Hillerman)

What I’ve Been Reading: September 2020 (Jo Gar, Sherlock Holmes, Casablanca the movie, more)

What I’ve Been Reading: January, 2020 (Glen Cook, John D. MacDonald, Howard Andrew Jones, more)

What I’ve Been Reading: December, 2019 (Scott Oden, Norbert Davis, David Dickinson)

What I’ve Been Reading: July, 2019 (Clive Cussler, Gabriel Hunt, Max Latin)

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

You can definitely ‘experience the Bobness’ at Jason Waltz’s ’24? in 42′ podcast.

Review: The Knight and the Moth by Rachel Gillig

Buy The Knight and the Moth

FORMAT/INFO: The Knight and the Moth will be published on May 20th, 2025. It is 400 pages and published by Orbit Books. It is available in hardcover, ebook, and audiobook formats.

OVERVIEW/ANALYSIS: "Swords and armor are nothing to stone." That's the mantra of Aisling Cathedral, home to the six Diviners who dream of Omens and predict the future for those who come before them. Sybil Delling is one such Diviner. Like those who came before her, she and her fellow sisters were foundlings who have given ten years of their lives in service to the Cathedral in return for a place to call home. But with just a few months to go before their tenure ends, Sybil's sisters start to disappear without a trace, until only Sybil is left. Fleeing for her safety, the only person she can turn to is the heretical knight Rodrick, notable for his disdain of everything to do with Omens. Together, then two journey forth in search of the missing Diviners, only to uncover a darker truth than they could have imagined.

The Knight and the Moth by Rachel Gillig is an absolutely beautiful gothic romance full of feminine fury. If the term "romantasy" (which I think is overly applied to any fantasy book that happens to feature a love story) is a turn off to you, I beg you to give this a second look. This isn't a race to get to spicy scenes; this is a slow burn romance of two people falling in love while exploring the dark mystery that surrounds the kingdom. While there is a spicy scene, it feels completely earned and keeps the descriptions fairly PG-13.

If you've read the author's previous Shepherd King duology, you may find some familiar beats in this plot, which is the one slight drawback to the story. Like the other series, there's an ominous kingdom full of dark forests and unforgiving landscapes, a group trying to collect magical items, and a romantic pairing at the center of it. But while I can spot the broad similarities, there's no denying the author executes the story extremely well.

In fact, in many ways The Knight and the Moth improves on the formula that came before (and I say this as someone who enjoyed the Shepherd King duology). I vastly preferred the romance in The Knight and the Moth to One Dark Window, finding Sybil and Rodrick equally matched foils who slowly move past their disdain for each other and find love. I also think the author does a much better job of keeping the main character of Sybil on the same pages as the reader, with her having epiphanies at the same time as me, instead of several chapters after the fact.

I also loved the growing evolution of Sybil of the course of the book. She begins to take strength from her anger at how her life has been controlled and manipulated. One of my favorite arcs of a character is when they go from relatively submissive to a strong individual capable of saying No to those who have taken advantage of them in the past. It was on full display here and it was glorious.

CONCLUSION: The Knight and the Moth earns every bit of its gothic romance label in the best way possible. It is atmospheric, romantic, and mysterious. It had me flying through the pages, and I am counting down the days until the sequel can be in my hands.

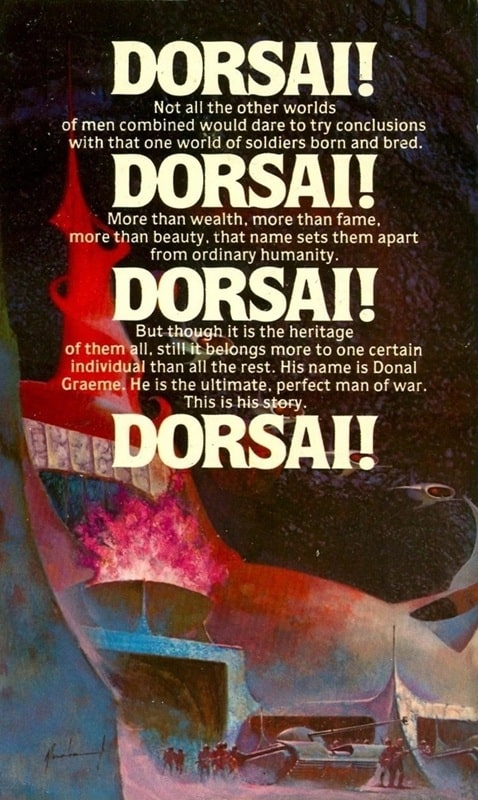

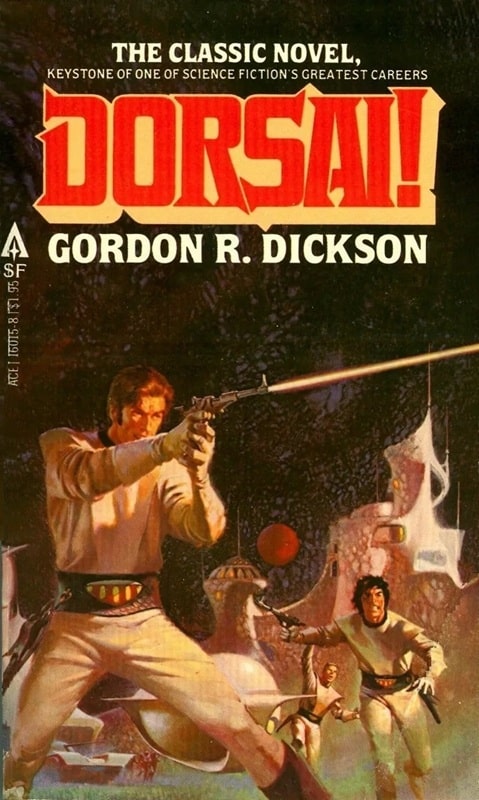

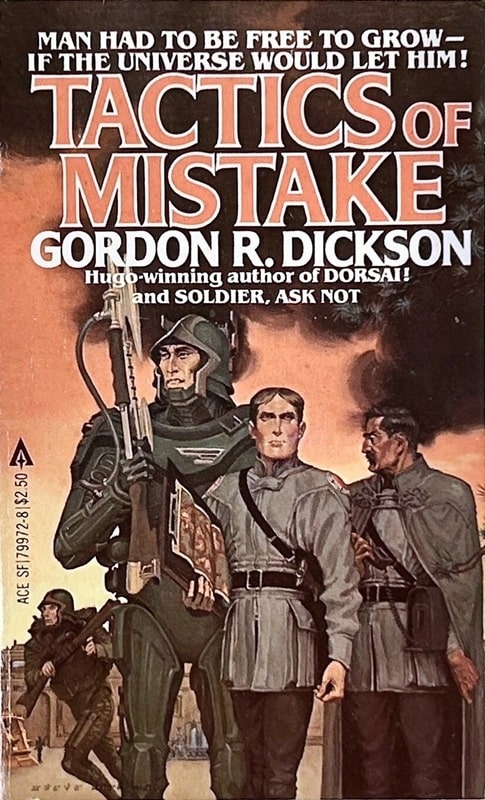

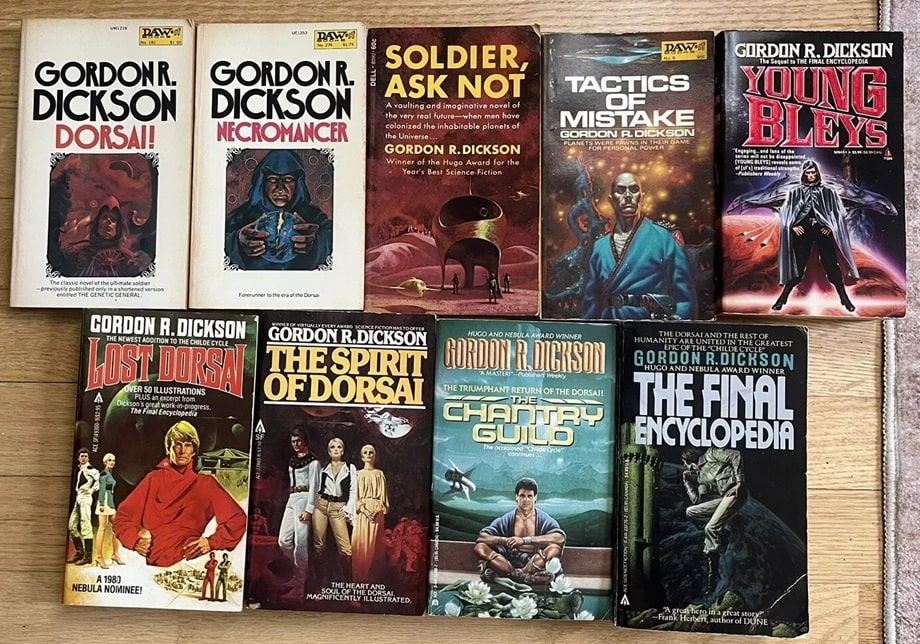

Shai Dorsai: Dorsai! by Gordon R. Dickson

Dorsai! by Gordon R. Dickson (Ace Books, February 1980). Cover by Jordi Penalva

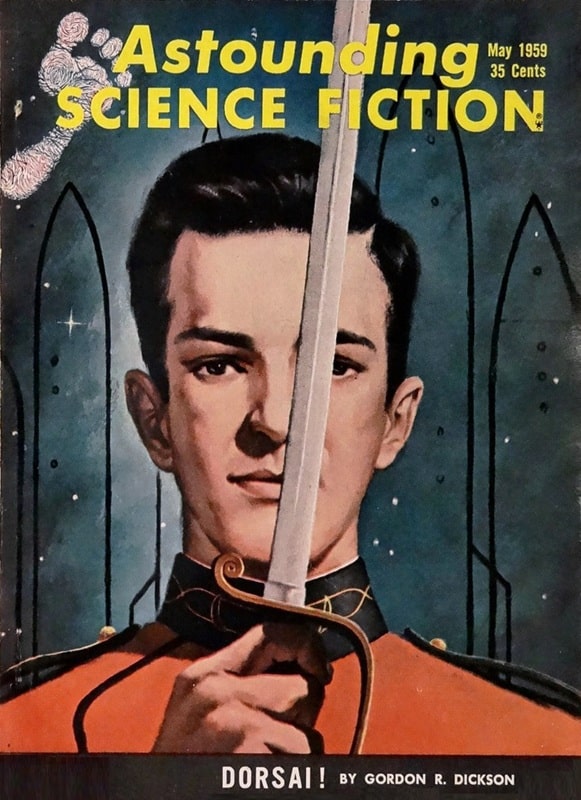

In 1959, Robert A. Heinlein published Starship Troopers, one of the founding works of military science fiction as a genre. But that same year saw the serialization of Gordon R. Dickson’s Dorsai! in Astounding Science Fiction, a work that may have been equally influential, though it seems now to be less remembered. In fact, both were nominated for the Hugo Award in 1960, though Starship Troopers won.

Dorsai! is set in an interstellar future, with some sixty billion human beings inhabiting 16 planets of eight solar systems. Several of the stars are named in the novel, and as was common at that time, many of them are astrophysically implausible candidates to have biospheres, being of spectral types with relatively short lifespans: Altair (type A7), Fomalhaut (type A4), and Sirius (type A0). Fomalhaut and Sirius are also multiple stars, which limits the possible planetary orbits around them. At least Ceta, orbiting Tau Ceti, is a plausible Earthlike planet! It’s also noteworthy that several of these solar systems have multiple habitable planets — though that’s also true of our own, where Dickson has Mars and Venus humanly colonized, a project that seemed far more daunting only a few years later!

Astounding Science Fiction, May 1959, containing the first installment of Dorsai! by Gordon R. Dickson. Cover art by H. R. Van Dongen

Astounding Science Fiction, May 1959, containing the first installment of Dorsai! by Gordon R. Dickson. Cover art by H. R. Van Dongen

But all this is somewhat beside the point, because unlike his lifelong friend Poul Anderson, Dickson isn’t writing about the physics of his planets, or the biology it enables. To a first approximation, his focus is sociology: the planets of his interstellar future have largely divided up into groups that emphasize different types of human activity, almost like the varnas [“castes”] of ancient India — and different ethical values along with them.

Thus, we have the “Venus group” (Venus itself, Newton, and Cassida), whose focus is on technology and the physical sciences; Ceta, a planet of commercial enterprises and investors; the “Friendlies,” Harmony and Association, two worlds of devout monotheists; the “Exotics,” Mara and Kultis, whose emphasis is partly philosophy (more in the Hindu or Buddhist style than in the Western) and partly a science of human potential, called ontogenetics, that apparently can be used for selective breeding for specific desired behavior.

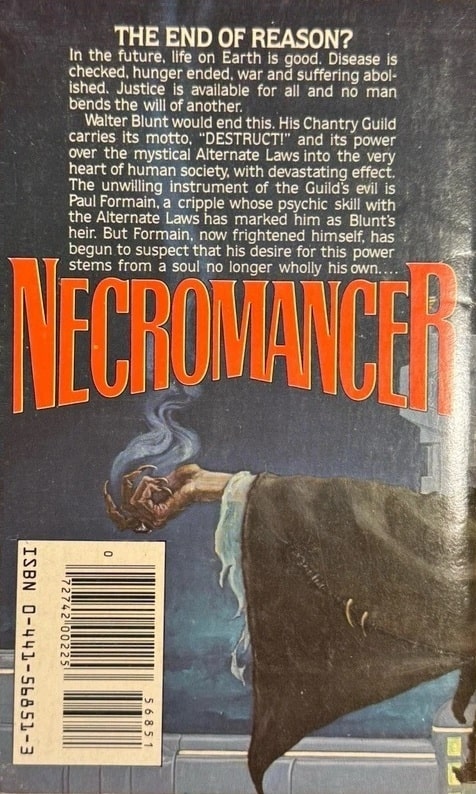

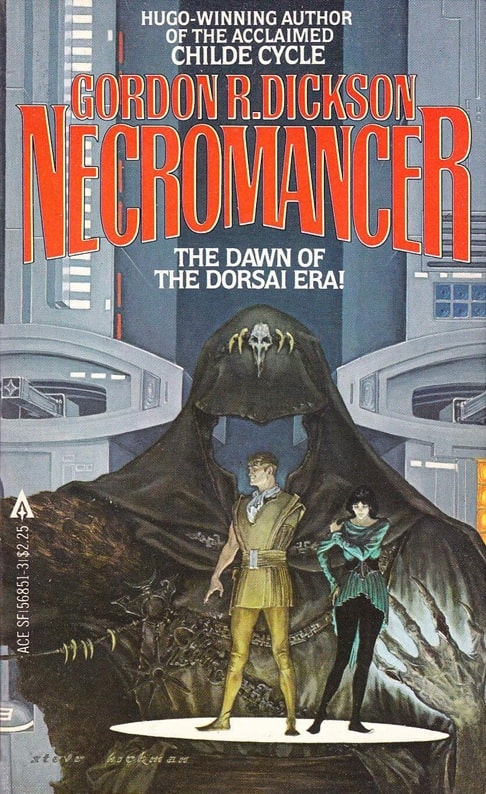

Book 2 in the Dorsai series: Necromancer (Ace, April 1981). Cover by Stephen Hickman

And then there’s the Dorsai, for whom the book (and several of its sequels) is named. It’s the name both of a planet and of the people who inhabit it. Compelled by a shortage of natural resources, their men hire out as mercenaries, known as the best soldiers in the humanly inhabited universe, both naturally talented at war and intensively trained. One of these is Dickson’s protagonist, Donal Graeme, the focus of the entire narrative.

This diversity of planetary societies sets up the novel’s conflict. In the first place, the planets are specialized, not merely in broad cultural patterns, but in economic detail. There are more specialized occupations than any one planet can afford to train for itself; the human race has a sixty-billion-person division of labor. This creates a need for specialists from each planet to travel to other planets where their services are needed, just as the Dorsai do.

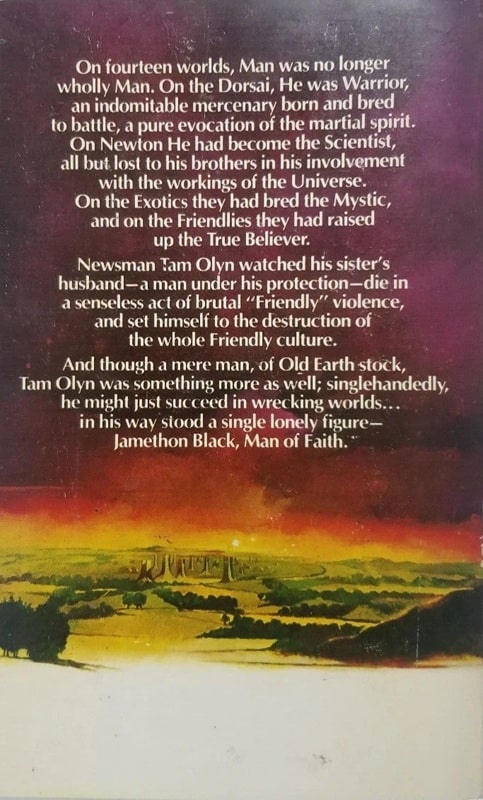

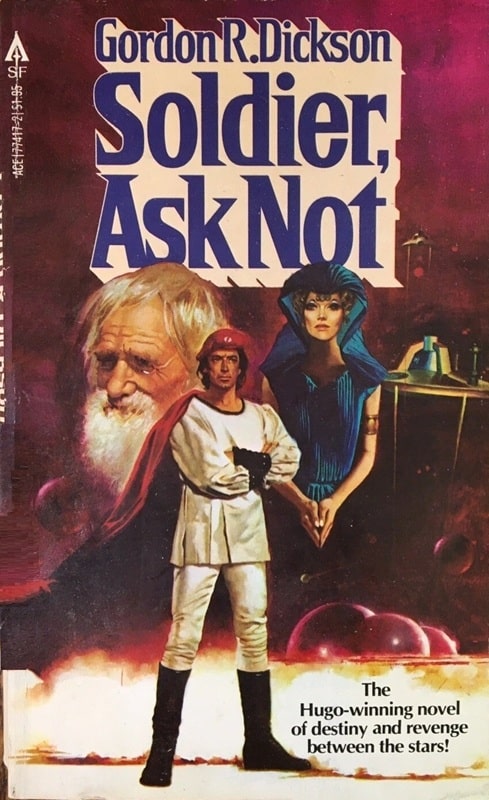

Dorsai, Book 3: Soldier, Ask Not (Ace, March 1980). Cover by Enric

But the terms on which they do so are set in different ways by different planets. At one extreme are the tight worlds: the technologically advanced Venus group, the religiously fanatical Friendlies, and Coby, a mining world controlled by a criminal cartel. At the other are Old Earth and Mars, described as “republican worlds”; the Exotics; and the Dorsai, which are counted as loose worlds.

In between are several miscellaneous worlds, including the commercial Ceta and two worlds with strong central governments, New Earth and Freiland. The tight worlds treat labor contracts virtually as indentures and are in a position to dominate the labor markets, putting them at odds with the loose worlds.

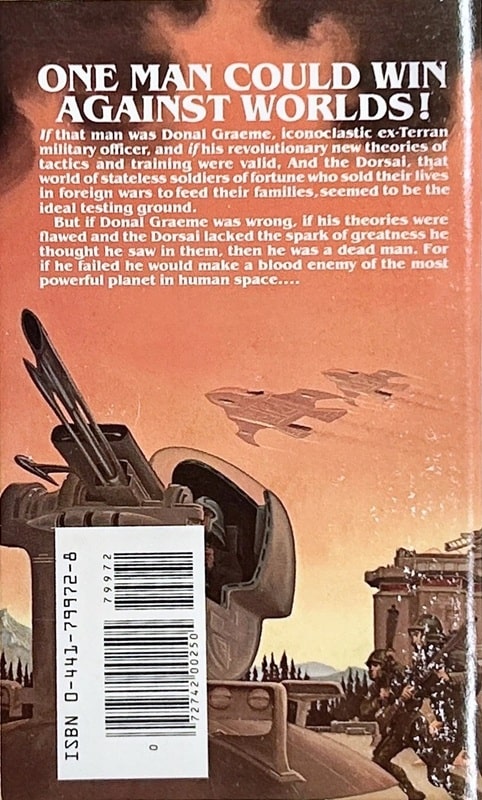

Dorsai, Book 4: Tactics of Mistake (Ace, May 1981). Cover by Stephen Hickman

It struck me on this reading that Dickson’s view of Harmony and Association seems to have changed as he wrote the series. Here they are harshly authoritarian societies with no evident redeeming features. In Soldier, Ask Not, published eight years later, they appear much more sympathetically, and it seems that Dickson’s unfinished final volume would have shown them as an essential element in the reunited human race — the element of faith, as the Dorsai are courage and the Exotics wisdom. (The other major tight faction, the Venus group, are seemingly left behind as having nothing essential to add to human destiny.)

Donal Graeme himself fits this theme of human reunification: both of his grandfathers were Dorsai, but both of his grandmothers Maran. (This hybrid ancestry made me think of another military genius in later science fiction, Lois McMaster Bujold’s part-Betan, part-Barrayaran Miles Vorkosigan.) This gives him a peculiar mix of abilities. He’s a brilliant warrior and commander, fitting a work of military fiction. But he also have some gifts that transcend normal humanity, as he’s told during his employment by the Exotics.

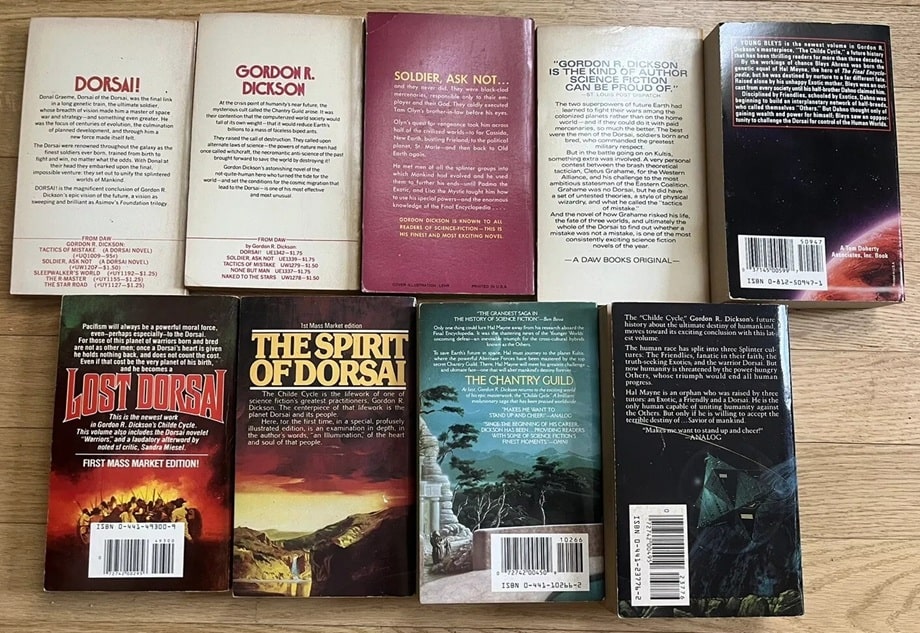

Nine paperbacks in the Dorsai series by Gordon Dickson (also called the Childe Cycle)

Nine paperbacks in the Dorsai series by Gordon Dickson (also called the Childe Cycle)

We get a foretaste of this when he finds himself able to walk on air, apparently simply by believing he can! But more profound than that is a peculiar kind of insight that deepens over the course of the novel, as a result of various stressful experiences. And that insight sets him up, almost from the outset, as an opponent of another major character: William of Ceta, a master entrepreneur whose aim is to take full advantage of the interstellar labor market.

Donal and William become both political and romantic rivals, but both rivals reflect Dickson’s underlying theme of human destiny and the question of who will shape it. In this theme, Dorsai! in a lot of ways transcends the category of military science fiction.

Nine paperbacks in the Dorsai series by Gordon Dickson (back covers)

Nine paperbacks in the Dorsai series by Gordon Dickson (back covers)

On one hand, this theme strikes me as more mythological than science fictional — which I’m not sure Dickson would even have disputed! On the other hand, it points the way toward the deeper emotional resonance of some of the later books, especially Soldier, Ask Not.

Dorsai! also sets a pattern Dickson will follow in later novels in the series, of presenting conflict ultimately not as a clash of institutions (despite his comments about loose and tight worlds) but as a collision of two larger than life figures on opposing sides: not so much realistic fiction as epic. This volume is a somewhat simple first presentation of the theme, but at the same time one of the clearest in the series.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last article for us was a review of Singularity Sky by Charles Stross.

Women in SF&F Month: Final Week & Week in Review

This year’s Women in SF&F Month ends this week with one more guest post and an international giveaway. Thank you so much to last week’s guests for their excellent essays! Before announcing the rest of this year’s schedule, here are last week’s guest posts in case you missed any of them. All guest posts from April 2025 can be found here, and last week’s guest posts were: “The Power of Community” — Pat Murphy (The Falling Woman, Points of Departure) […]

The post Women in SF&F Month: Final Week & Week in Review first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Tubi Dive, Part III

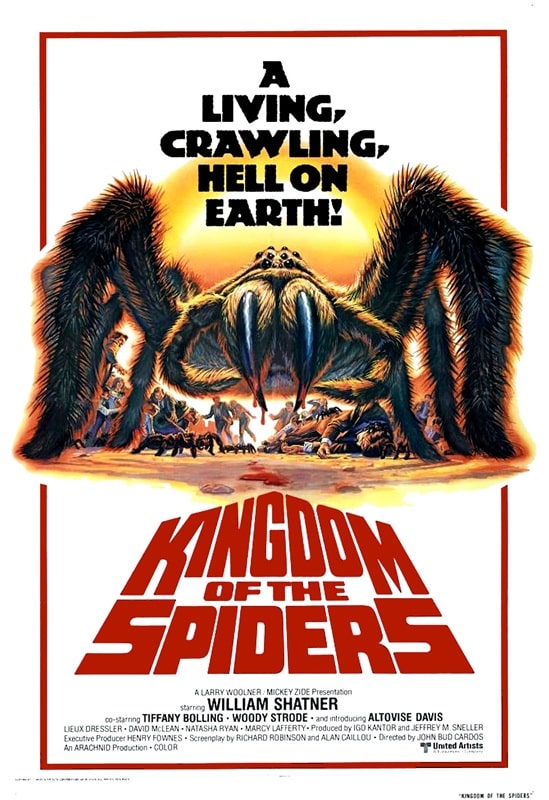

Kingdom of the Spiders (Dimension Pictures, November 23, 1977)

Kingdom of the Spiders (Dimension Pictures, November 23, 1977)

50 films that I dug up on Tubi.

Enjoy!

Kingdom of the Spiders (1977)Ah, the 70s. My formative years. Angry nature films were rampant around this time (much to my delight), and now it’s time for tarantulas to be miffed at our overuse of pesticides.

William Shatner plays Rack Hansen (staggeringly good name), a lecherous animal doctor in rural Arizona. When I say lecherous, I mean toward female humans. When Woody Strode finds his prize calf dead, the Shat is called in to figure it out. He calls in an expert from Flagstaff, and unfortunately for the expert, she is hot and blond. Shatner is all over her like tribbles on a starship.

They eventually ascertain the death was caused by spider bites, and then all eight-legged hell breaks loose.

The film is seriously daft in some spots, egregiously misogynistic in others, and cheesy to the extreme, but I had a great time with it. The climax in town is particularly Irwin Allen-style over the top chaos, and the final shot, though portrayed through a sub-par matte painting, is suitably chilling.

Worth a look if you haven’t seen it.

7/10

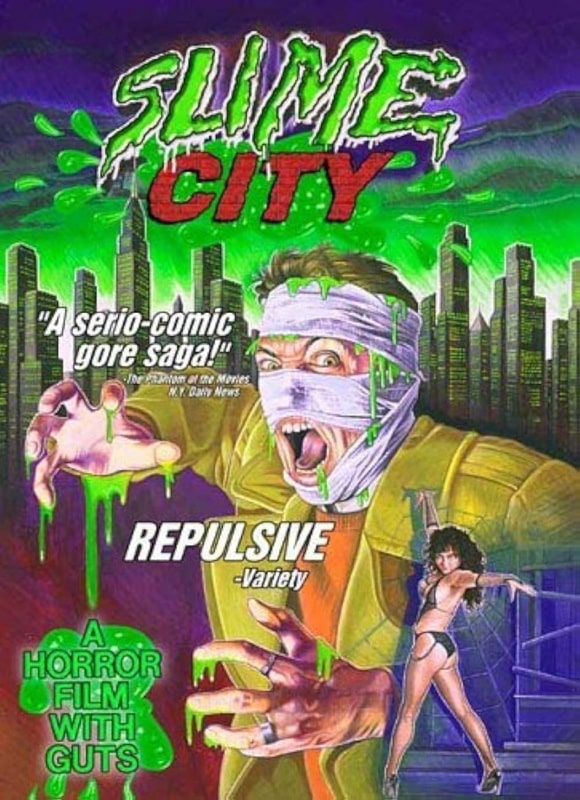

Slime City (Media Blasters, 1988) and Little Corey Gorey (DML, 1993)

I’m sometimes asked why I haven’t gotten around to watching The Brutalist or Wicked yet, and that’s because I’m too busy watching this sort of stuff.

Alex moves into a decrepit apartment building and soon encounters some fellow tenants (goth poet Roman and seductive vamp Nicole), both of whom are into eating ‘Himalayan yogurt’ and drinking a strange green liquor. It turns out these vittles are the sustenance of cultists who have possessed their bodies, and Alex is next in line. Tempted by the drink and Nicole’s jangly bits, Alex succumbs to the dark sorcery afoot, and slowly turns into a slimy murderer, ultimately going full Darkman. As you do.

It’s all quite daft and low-budget, but the dodgy line delivery and goop-stained pillows are all worth it for the final act, which involves Re-animator-levels of dismemberment (albeit less refined).

Alex’s prudish girlfriend and sex crazy Nicole are played by the same actor, Mary Huner, and I have to give her credit for fooling me. The effects are mucky and rubbery, and there are a couple of funny lines, mostly from Alex’s doofus pal.

A good entry-level flick for other fare such as Street Trash or The Abomination.

Slightly recommended.

6/10

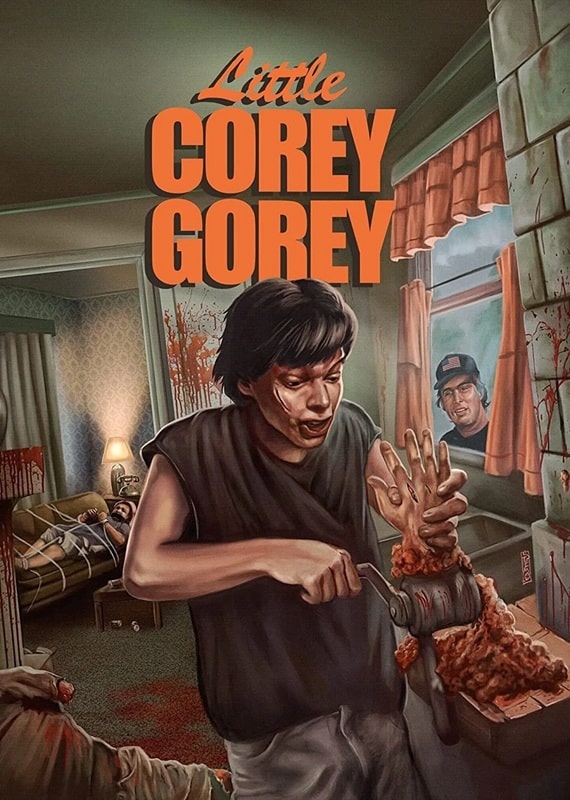

Little Corey Gorey (1993)I’ve seen this one listed as a comedy (it’s not), and a slasher (still not), but at the end of the day, Little Corey Gorey is just a nasty bit of schlock, and not the good kind.

It’s that timeless story of a teen (9th grader) bullied and tortured by his step-mother and brother to the point where he snaps and goes on an accidental killing rampage. There’s not much else to the plot, but that usually doesn’t bother me when I’m watching one of these flicks.

However, virtually all of the main characters are so cartoonishly vile, including our ‘protagonist,’ that it was ultimately a miserable watch.

Corey, for whom we are supposed to be rooting, is a creepy, knicker-sniffing stalker and, though he certainly doesn’t deserve the abuse from his step-family, it’s impossible to sympathize with him. The only characters in this film with any decency are a Black family that live next door, and I trust this was done for a reason. There is an ongoing subplot about an escaped serial killer, but this one is nipped in the bud fairly quickly when it could have been used in a far more interesting way.

3/10

Rituals (Astral Films, August 26, 1977)

Rituals (1977)

Rituals (Astral Films, August 26, 1977)

Rituals (1977)

Here’s a Canadian film (shot in Northern Ontario) that is often dismissed as a Deliverance rip-off — but it’s much more than that. Sure, it takes the form of the tried and tested ‘fish out of water’ genre by throwing five surgeons into the remote wilderness to try and survive a deranged killer, but there’s a grittiness to the whole affair that elevates the film. Also, the characters are well-written, and an early scene where they are trying to cross a river, a scene full of unintended plunges and improvised cajoling, helps us to empathize with the group before their nightmare begins.

The kinetic camerawork gives the film an authenticity, and semi-obscured shots from the killer’s POV provide a real sense of danger. Before this film I’d never really appreciated Hal Holbrook as anything more than an interesting character actor, but he really impressed me with his physical and emotional depth.

Definitely worth a look.

8/10

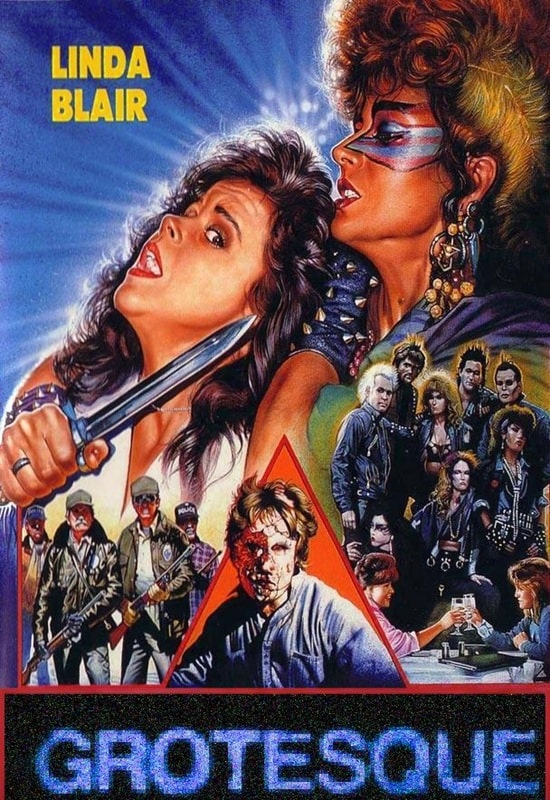

Grotesque (Empire Pictures, 1988)

Grotesque (1988)

Grotesque (Empire Pictures, 1988)

Grotesque (1988)

You want weird, and yet strangely compelling? I’ve got you.

Grotesque is executive produced (and briefly stars) Linda Blair, and Tab Hunter has a main role in it, along with Donna (Angel) Wilkes, so the schlocky cult movie DNA is intact. However, this home invasion horror is such an odd beast; bookended by a couple of movie fake-outs, and being a lot tamer than one might expect for a film that has special effects at its core.

The tale is as old as time: a special effects artist invites his family to their remote lodge, where they are set upon by a roving gang of ‘punkers’ who proceed to slaughter said family. This is witnessed by a disfigured man-child, who promptly goes on a murderous punk-slaying spree, and then the film shifts gears into a boring police procedural complete with prolonged ‘good cop/bad cop’ routine, while Linda Blair excuses herself offscreen. Then it turns into a sort of Twilight Zone episode and then descends into a ‘comedic’ finale (your experience may vary).

My brain is telling me I enjoyed it — but I really don’t listen to my brain any more.

5/10

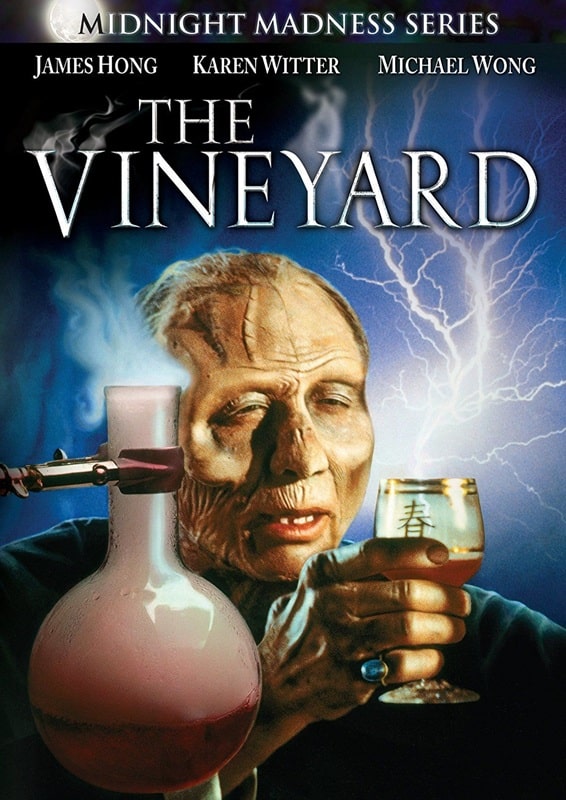

The Vineyard (New World Pictures, 1989) and

Insect! (International Spectrafilm, September 25, 1987)

James Hong, right? RIGHT?

We all love him, from Big Trouble in Little China to Everything Everywhere All At Once, from Kung Fu Panda to Balls of Fury.

James decided he wanted to make a horror film, so he wrote one, co-directed it, and starred in it. What makes him a legend? Did I mention he wrote this for himself?

EXT. DAY

A large, gothic mansion bordered by lush foliage. A bird cries in the distance.

DR. PO (me, James Hong) is standing on a balcony, fondling the pert chesticles of a blond lady.

CUT TO:

INT. BEDROOM

DR. PO (me) is having it away with the blond lady. She’s still naked.

DR. PO (me)

Awesome. I love knockers, me.

You go, James Hong!

The Vineyard is a tale as old as time (again). The descendant of a long line of immortals has become a famous vintner, but his secret ingredient is chained up ladies, of whom he supps in a strange concoction to maintain his youth (his middle age TBH). When he’s finished with them he buries them in the back yard where they lay as restless zombies, unable to rise because he is keeping them in the ground with Mayan voodoo.

Dr. Po holds a fake audition at his mansion for a fake film and a lot of pretty girls and boys turn up for it, only to discover that they are mere ingredients for his latest vintage. Po is also keeping his ancient mom in the attic room, and she is a dead ringer for Zelda from Terrahawks (if this means anything to you).

Shenanigans ensue, involving much running, shooting of arrows, extremely heavy facial prosthetics and dodgy late 80s visual effects. It’s drastically cheesy and somewhat hilarious, and I had a great time. God bless James Hong.

7/10

Insect! (aka Blue Monkey) (1987)Find any dictionary worth its salt, look up ‘hokey’ and you’ll find the poster for this film. Then you’ll see a small print addendum that reads “see also: hilariously awesome.”

Insect! is a proudly Canadian schlockfest, and it features a who’s who of the best Canadian character actors; John Vernon, Don Lake, Joe Flaherty, Robin Duke, and a 7-yr-old Sarah Polley!

The main protagonist is a weather-beaten detective played by Steve Railsback, who I always thought had more of a serial killer look than a leading man, but hey ho — I’m sure he has his fans.

Long story short, an old fella is infected by a parasite, which promptly busts out of him, grows enormous, makes itself a mate and goes into egg production, all the while eating the hospital staff.

Speaking of the hospital, this has to be the most unsecure, ethically murky, run-down medical establishment ever put on film — and I’ve seen Session 9.

Anyhoo, nurses are eaten, bugs are squished and Steve smokes next to a pregnant lady. The gore is limited but gooey, and the effects on the whole are surprisingly fun. Special shout out to a gaggle of seemingly parent-less children who run free around the hospital (and are, in fact, responsible for all the deaths in the film).

See it if you enjoy stickiness.

6/10

Previous Murkey Movie surveys from Neil Baker include:

Tubi Dive, Part I

Tubi Dive, Part II

What Possessed You?

Fan of the Cave Bear

There, Wolves

What a Croc

Prehistrionics

Jumping the Shark

Alien Overlords

Biggus Footus

I Like Big Bugs and I Cannot Lie

The Weird, Weird West

Warrior Women Watch-a-thon