https://www.blackgate.com/

New Treasures and Interview: C.S.E. Cooney’s Saint Death’s Herald

Black Gate’s interview series on “Beauty in Weird Fiction” queries authors/artists about their muses and methods to make ‘repulsive things’ become ‘attractive.’ We’ve hosted C.S. Friedman, Carol Berg, Darrell Schweitzer, Anna Smith Spark, and Janet E Morris (full list of 29 interviews, with Black Gate hosting since 2018).

This round features C. S. E. Cooney (CSEC), who is no stranger to Black Gate [link to listings]. She is a two-time World Fantasy Award-winning author: first, for Bone Swans: Stories, and most recently for Saint Death’s Daughter. Previously on Black Gate, an all-star crew heralded its release with a video cast including readings of Saint Death’s Daughter by C.S.E. Cooney.

Forthcoming in April 2025 is Saint Death’s Herald, the second in the Saint Death series. In this post, we reveal exclusive details, CSEC’s creative process, and hint of Book #3’s contents! Read this and her contagious energy will infect you! Cripes, simply by doing this interview, I was infected with a buttery aura! Read more and learn C.S.E. Cooney’s real identity and code name too (Tiger of the gods? Or is it Lainey!)

An Interview with Saint Death’s Daughter (a.k.a. C.S.E. Cooney)SEL: Saint Death’s Daughter was released in 2022, and we’ll dig into that momentarily. Mark Rigney interviewed you a decade ago Black Gate (2014 link). How have you changed as an author since then? Were you inspired by your Lord Dunsany readings?

Re-reading that 2014 interview is hilarious. And exuberant. And painful. Oof. That line towards the end about Howard making me read Lord Dunsany? Seth, I have to say that right now, I just want Howard alive again, and making me read anything at all. That’s what I want.

[SEL Sidebar: Howard Andrew Jones, Black Gate print magazine editor, longtime author, and friend/mentor to countless writers, passed away this January after battling aggressive brain cancer. CSEC led the charge with a GoFundMe campaign for his family (with help from a crew including the just-mentioned Mark Rigney), and Black Gate has hosted several tributes (i.e., from John O’Neill, Jason Ray Carney, & Bob Byrne); as one of HAJ’s Skull Interns, I am capturing links to many more memorials. Peace to our dear friend.]

Otherwise, sadly: I don’t recall much about my Lord Dunsany readings. I didn’t even remember that reading Dunsany made me want to be referred to as “the tiger of the gods.” Now, why didn’t that catch on, I wonder? You may henceforth refer to me in this interview as “tiger of the gods,” please.

Have I changed as an author since then? Yes. Yes, I’m not as fast as I was ten years ago, and everything about the world seems harder, and sadder. I think it was always hard and sad, but I’m feeling it more now, I guess.

But also… also, it’s all so much more interesting.

Over the last ten years, I’d experienced such burnout, such weariness and bitterness about the craft, that at one point I announced I wasn’t going to write again until I wanted to write. My friends and family were afraid I was serious. (I was.) They were like, “Claire, what are you doing?”

But I really just wanted to want to write. Was any of the work even worth it if I didn’t want it anymore?

And it took a few weeks of me staring out a window, giving myself permission not to write. But then, suddenly and spontaneously one morning, I had one of those magical “what if” thoughts. That was something that hadn’t happened in literally years of revision and submission and revision and submission. The next morning, that “what if” had built into a whole dang story idea. So I sat down and started writing it out long hand — something I’d also not done in years. The experience was so pleasurable, so permissive, and so, I don’t know. Healing.

The whole world seemed new. Writing was possible again. Phew! I’d made it through the wasteland and to the other side.

Since then, the whole creative process just keeps getting weirder and more wonderful. Concentrating on the unique bizarreness of process has really opened me up to so many branching avenues of boundless curiosity.

Now I know: if I need to stop writing for a while, I will. (After I meet my deadlines, of course. That’s what a professional does.)

For me, the sensual ritual of writing has become the point. And community. Community is the point.

What else has changed? I’ve never done so much body mirroring while writing in my life: writing in silent zooms, or with people in the room. I’ve never done so much timed writing. I even started listening to music while writing — which I never used to do. I still can’t listen to anything with words (some Hildegard von Bingen chanting aside). I started listening to fantasy gaming soundtracks, because if I listen to movie soundtracks, I just have that movie’s story and dialogue running through my brain. But since I’ve not played most fantasy games, that’s not a problem. (I can’t, for example, listen to the Baldur’s Gate soundtrack, because I did play that. Which was awesome.)

I know this now: even when I’m sad, and tired, and lacking all motivation, I still want to want to write. All the rest is hacking my brain to get the motor running. Music, company, handwriting, candlelight… all of those rituals put me in a more celebratory and ludic headspace for writing.

What’s the same? Well… every time I have to write something new, it’s still like learning how to write all over again. Some of the same skills apply, sure, but I’m constantly learning how to write something I couldn’t even fathom before I started.

Like fight scenes. Fight scenes are so hard.

“Henceforth refer to me in this interview as ‘Tiger of the Gods’ ” — C.S.E. Cooney Saint Death’s Daughter (2023 World Fantasy Winner) Blurb

Nothing complicates life like Death.

Lanie Stones, the daughter of the Royal Assassin and Chief Executioner of Liriat, has never led a normal life. Born with a gift for necromancy and a literal allergy to violence, she was raised in isolation in the family’s crumbling mansion by her oldest friend, the ancient revenant Goody Graves.

When her parents are murdered, it falls on Lanie and her cheerfully psychotic sister Nita to settle their extensive debts or lose their ancestral home — and Goody with it. Appeals to Liriat’s ruler to protect them fall on indifferent ears… until she, too, is murdered, throwing the nation’s future into doubt.

Hunted by Liriat’s enemies, hounded by her family’s creditors and terrorised by the ghost of her great-grandfather, Lanie will need more than luck to get through the next few months — but when the goddess of Death is on your side, anything is possible.

At first glance, the summary of Saint Death’s Daughter sounds like a horror adventure, but it reads more like a comedic/fun, coming-of-age story. How would you describe the book to new readers?TIGER OF THE GODS: Generally, I give this elevator pitch: “Girl grows up in a family of assassins, but is allergic to violence. Her allergy indicates that one day, if she survives long enough, her aversion to violence will be so strong, she’ll be able to RAISE THE DEAD.”

Boom! Necromancy book, baby.

For comp titles, I say something along these lines: “Like if Terry Pratchett and the Addams Family had a necromancer baby who really liked pink frilly dresses and cutie patootie mouse skeletons.”

Those are light, easy ways about talking about my book. My book which is, in reality… much weirder.

BUT! I really don’t want to intimidate people. I want to invite people.

I also like to describe Saint Death’s Daughter as a Bildungsroman — a coming-of-age story. Now, I know that all YA books must perforce be coming-of-age stories. That’s the genre. It’s just that, at no point in the drafting process, did I imagine I was writing YA with Saint Death’s Daughter. But it is still a Bildungsroman.

I am, as I was ten years ago, still under the influence of Lois McMaster Bujold. I wanted to write a character like Bujold’s Miles Vorkosigan. The first few novellas about him may have covered his childhood, but over time, we get to experience him at many ages.

Saint Death’s Daughter is just Lanie Stones’s first book. It’s just one point in the timeline of her full life — perhaps not even the most important part. I imagine her in her thirties. (Sexy beast!) Her forties! (Whoa, what a powerhouse!) I imagine her as an old woman — with even more wisdom and compassion and mischief, and far, far more powerful. (Also, probably a foodie.) I imagine her on her deathbed. I imagine future scholars writing about her as a historical figure of a certain time and place that is perhaps no more. (This makes footnotes very fun.)

SEL: Discuss the media of necromancy which feels very artistic, especially the paint-like, colored essences of panthuama and ectenica.TIGER OF THE GODS: I made up the word “panthauma” out of the words “pan” (all) and “thaumaturgy” (miracle or marvel-working). I wanted a word for sorcery that was slightly alien, so I could apply my own set of rules to it without previous reader bias. But I also wanted, in addition to that whiff of mysterious, a sense of familiarity, linguistically-speaking.

And then I wanted a new word for “death magic” that wasn’t just, you know “death magic.” “Necromancy” is the obvious word, and I do use it in the book. But its actual etymology has more to do with divining via the dead than raising them up. (All the “-mancy” words have to do with divination.) So I wanted necromancy to be a specific kind of death magic, not the word for death magic.

I wanted a new word, something more flexible, less familiar. A word that evoked ghosts! And also super fun to say. So I took a closer look at our word “ectoplasm,” and then just sort of f*&%ed with it to make “ectenica.” Just say it aloud. All those clicky consonants!

Lanie’s a bit of a synesthete, in that she associates smells and colors with magic; that’s her brain trying to process the unimaginable. So, for panthauma, when the gods are drawing close and lighting up the world with Their attention, her vision goes bright-yellow with hard edges, like faceted topaz, and her body responds with a kind of champagne-y, effervescent reaction. Her sensual reaction to ectenica is much colder. She perceived it as a sort of starry blue. And the smell of her god, and of death magic, is always some variation of citrus. Other gods have other smells. I think, to some degree, most of the sorcerers/saints in my world have synesthesia.

SEL: Celerity Stones, one of Lanie’s aunts, was also a traditional artist, and her portfolio included portraiture like “Barely There: The Exquisite Art of Excoriation, With (Predominantly) Live Models”. I’d love to see her collection. Can you tell us more about Celerity’s inspiration and art?Celerity had been much in demand for her pen and ink drawings, her sanguine sketches, her oils, watercolors, and illuminated calligraphy. Later, she won renown as an anatomical scientist. Very precise with spreader, was never easy to ignore her most famous work, The Flayed Ideal, which hung on the wall of Stones Gallery and had a way of glaring at you. Its exposed and accusatory eyeballs, rendered in oil on canvas with exquisite delicacy, followed you around the room — and very often out the door and down the hall.

— from Saint Death’s Daughter

TIGER OF THE GODS: You know those stories we have of anatomists and resurrection men in prior centuries who’d illegally dig up bodies in order to study them, to become better doctors? (I’m glad that the laws — and some minds — have changed to allow for voluntary donation in such endeavors, but for a while it was considered absolutely heinous.) And you know all those stories about how powerful people in history — doctors, surgeons, psychologists, prisons, military — exploited marginalized communities, sometimes going so far as to medically experiment on people without their informed consent, for purposes of their own research?

That’s my inspiration for Celerity Stones.

She was not a good person. She was talented and precise and obsessed with her work. But she — like the whole toxic Stones family — hurt people to achieve her greatness.

One of the reasons that the Stones family ultimately falls is that cruelty like that is not sustainable, however it sometimes seems to advance society in the moment. Undoing the Stones’s legacy, and especially the glamorization of the violent family narrative, is something that Lanie has to consciously learn how to do as she gets older.

SEL: Every time I’ve seen you at Gen Con, you are wearing impressive regalia. Do you craft the costumes? Do they represent characters?TIGER OF THE GODS: I don’t craft costumes, per se. Like, I don’t think of myself as dressing up as certain characters. But I do dress according to my mood that day — or the mood I’d like to have. Heck, I just like dressing up. When I was a kid I had a “dress-up trunk” and I just preferred every secondhand prom dress and thrift store “glass slipper” (plastic with rhinestones) and dilapidated tiara to any of my school uniforms, softball jerseys, or neon skorts in my regular wardrobe. All these years later, I still do. Only now MOST of my closet is “dress-up” trunk.

These days, if I have to dress to go somewhere where there’s an expectation of dress code, that’s when I feel like I’m in costume. Like, when I go into the booth for audiobook narration, I have to wear “soft clothes.” I think of them as “ninja clothes,” but a friend of mine said it just looked like I was wearing pajamas. But you can’t wear anything that tinkles or rustles or chimes!

I was watching a “maximalist” influencer talking on Instagram about how the act of getting dressed is a creative process. And when you put together an outfit (or “fit” as the kids are calling it) to completion, you get that little bump of dopamine, like when you finish a puzzle or complete a recipe or win a game. Creative clothing is a small, achievable goal, and it makes me happy. Maybe, in some ways, I’ve been sartorially self-medicating since childhood!

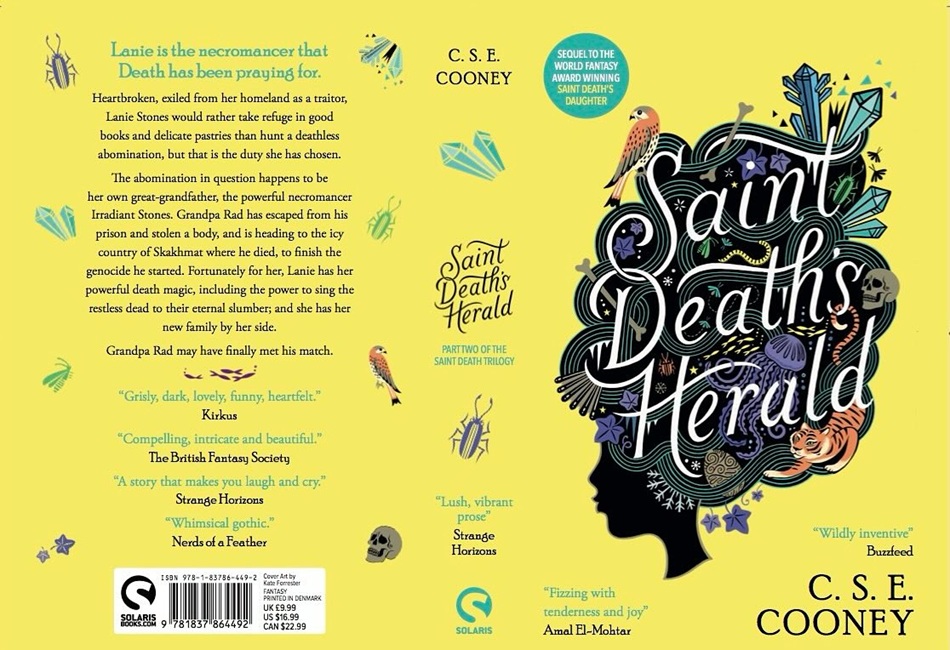

Saint Death’s Herald BlurbMuch-anticipated follow-up to the whimsical, joyous, zombie-packed World Fantasy Award-winning Saint Death’s Daughter

Lanie Stones is the necromancer that Death has been praying for.

Heartbroken, exiled from her homeland as a traitor, Lanie Stones would rather take refuge in good books and delicate pastries than hunt a deathless abomination, but that is the duty she has chosen.

The abomination in question happens to be her own great-grandfather, the powerful necromancer Irradiant Stones. Grandpa Rad has escaped from his prison and stolen a body, and is heading to the icy country of Skakhmat where he died, to finish the genocide he started. Fortunately for her, Lanie has her powerful death magic, including the power to sing the restless dead to their eternal slumber; and she has her new family by her side.

Grandpa Rad may have finally met his match.

Saint Death’s Herald (preorder link) is coming in April 2025. What can we reveal? Anything special we can say about this, only heralded via Black Gate?TIGER OF THE GODS: Oh, gosh. Well. A Black Gate exclusive, eh?

Well, here’s the thing. I LOVE spoilers. I don’t even call them spoilers. I call them SPICERS. But not everybody (not even most people) think of them that way. So, with the caveat that those people who consider any information at all a SPOILER, perhaps they could skip this part?

Hush, come close! I’ll tell you, dear Black Gate readers, that Lanie Stones has only grown in power since Saint Death’s Daughter. I’ll tell you that when she enters fully into sympathy with a dead object, she can… SHARE PARTS OF ITS SHAPE.

She is also learning how to communicate through the dead — so if she has a… a toe bone, for example, from a particular corpse, and if you have a different toe bone from that same corpse, she’ll be able to call you. Like a one-way cell-phone.

My plan is, for Book 3, that Lanie will be so good at sharing shapes with the dead, that she can basically take on and maintain the appearance of any dead creature whose accident (physical material) she is in contact with. This makes going undercover to investigate crimes against the death god (totally random plot idea, not the basis for Book 3 at all, doo-dee-doo) much easier.

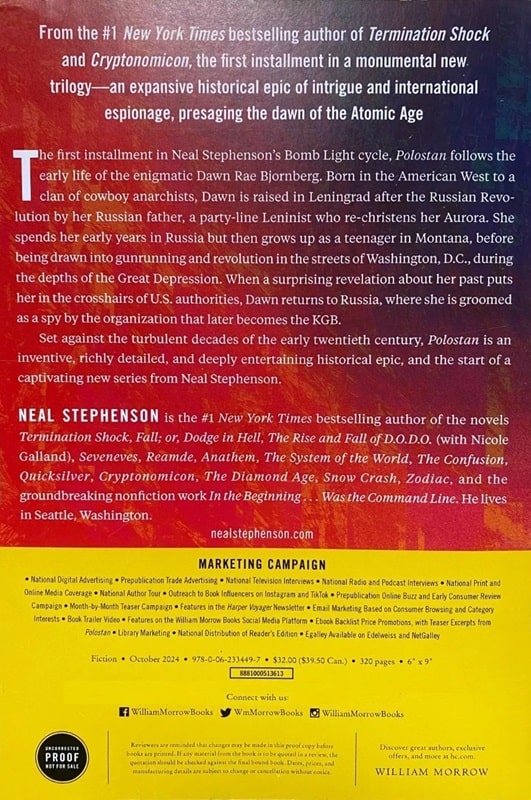

Can you discuss the cover art creation and artist?TIGER OF THE GODS: Oh, this is the wonderful, wonderful Kate Forrester! Fantasy readers will already know and love her work from such glorious novels as Zen Cho’s The True Queen and Theodora Goss’s Extraordinary Adventures of the Athena Club trilogy. Basically, for Book 1, my editor Kate Coe consulted me about different cover artist options, and some ideas for the art.

When Kate Forrester was chosen, Kate Coe and I generated a few wild cover ideas to throw her way. Then Forrester came up with the wonderful silhouette idea. My editor asked if I could send the artist a few elements from the book that the silhouette could have trapped in her hair.

Then, for Saint Death’s Herald, my editor David Moore arranged the same sort of information exchange. In Book 2, the silhouette is facing the opposite direction, with different elements caught in her hair. The cover was done long before the book was done — so I had to make sure that my final draft included all the visual cues that I had originally suggested when I was still in the early stages of writing! Phew!

I wonder what Book 3 will look like? Forward facing? Or two silhouettes facing in opposite directions? That would be kind of cool: especially if Lanie spends most of the book incognito — as both herself and not herself!

But that’s years away.

“For me, the sensual ritual of writing has become the point. And community. Community is the point…even when I’m sad, and tired, and lacking all motivation, I still want to want to write” – C.S.E. CooneyI adore your character names. For example, the protagonist & heroine “Lanie Stones” has a formal name of “Miscellaneous Stones”; and her contentious grandfather Irradiant ‘Grandpa Rad’ Stones. Can we contract you to assign us pseudonyms with all the grandeur your characters’ names have? I’d love to lure you into calling me names.

Tiger: That sounds like SO MUCH WORK! But it reminds me of the Fairy Tale Heroines workshop that The Carterhaugh School of Folklore and the Fantastic runs. One of the last things everyone does is assign themselves a “fairy tale heroine” (or hero/non-binary) name. But to do this, here are some questions: What’s your favorite animal? What kind of magic user would you be? If you could choose one of these to be: human, gentry (fairy folk), or goblin, which one would you be? If you were to choose one of the 12 gods from Saint Death’s Daughter, which would you choose? What’s your favorite obscure or forgotten word?

SEL: Eh gad, return fire. Those are hard questions! Fairy and “humors” (alchemical medicinal version) … and I am still learning the 12 gods of your stories. I’m too young and ignorant to recall them all and choose (I’m not worthy). I do love Lainey and her scarecrow though.

Tiger: Okay, then, so if you were a Stones, you’d probably be named Butter-of-Antimony Stones, son of Alkahest and Argyropoeia Stones…. Friends would call you “Bu” for short. (We won’t get into what your enemies call you.) And if you were a gentry, you probably would be named Crasis, a cloudskin (sometimes “cloud — skin” and sometimes “clouds-kin”) who can transform into whatever shape they please, though you will be insubstantial as vapor.

SEL: Okay, I want to know your secret Stoneses name too.

Tiger: Miscellaneous, of course!

BU: You are an award-winning poet (Rhysling Award-winning poem “The Sea King’s Second Bride” included in How to Flirt in Faerieland and Other Wild Rhymes), and have written plays. The previous Black Gate interview mentioned you also sing! Please discuss how expression works across media.TIGER OF THE GODS: Oh, gosh. I’m just drawn to some kinds of media over others. Like, I don’t have any current desire to write a screenplay or a graphic novel or MG/YA. But I often get the itch to write plays and musicals and poetry.

I just wrote a 10-minute play to submit to a local theatre festival for fun, and it felt so good to stretch those playwriting muscles again. My husband Carlos wrote one too! We both submitted to the same festival. Whatever happens now, at least we’ll have done something that challenged us artistically and brought us delight.

Re: musicals and albums: for the past few years, as time allows, I’ve been collaborating with Tina Connolly and Dr. Mary Crowell on a 6-episode musical theatre podcast called The Devil and Lady Midnight. And in 2023, I mounted a short, collaborative musical called Ballads from Distant Stars, with songs by myself, Amal El-Mohtar, and Caitlyn Paxson (with occasional melodies and harmonies by my brother Jeremy Cooney and Dr. Mary Crowell).

Eventually, I’d love to figure out how to bring both of the projects to full audio production. I’ll probably record Ballads from a Distant Star myself, with the help of my awesome musician brothers, and helpmate husband — like I did with my Brimstone Rhine album and EPs. However, The Devil and Lady Midnight will be a lot more complicated and expensive — but super rewarding if we can do the work!

What I’ve learned over the last 10 years about making albums and theatre: without an infrastructure already in place, a space to perform in, and people wanting to produce the work for you, you have to build that infrastructure from scratch. So there’s either a lot of crowdfunding involved, so you can hire people who already know what they’re doing to help you, or you’d better be ready to go full autodidact and learn how to do it all yourself. Whichever way you go, there’s still a cost: in time, in equipment, in the goodwill of the community, etc.

I try to find collaborators who are interested in making art for art’s sake with me. It’s not like I think we shouldn’t get paid, but I don’t really go into a creative project dreaming about all the money it might rake in. That said, I’m interested in collaborative partners who, once the creative process part is done, are also interested in taking that piece of polished art to production or publication — either via crowdfunding, bootstrapping, submitting, or grant-writing. Because it’s really daunting to try to run that gauntlet alone.

I also adore writing poetry. I stopped for a while — though in that lacuna, I did start writing songs — and now that I’m writing poetry again, I’ve got enough for a collection. I’m calling it The Day I Superglued the Moon: 10 Years in the Life of a Speculative Poet. It’s massive. It needs curation. I don’t know what to do with it. Self-publish? Ask my agent to submit it? Approach a small press?

Meanwhile, I feel so raw and tender and personal about it, because it’s poetry! so I keep avoiding doing anything at all. For now.

BU: ‘Macabre and beautiful’ (and fun) has even taken root in a game! You and your husband Carlos Hernandez co-designed a table-top roleplaying game called Negocios Infernales, Kickstarted October 2023. What is this game about? Does it inspire storytelling? Weirdly beautiful stories?“In the initial design, taking this all into account: here’s what we did. One of Claire’s favorite games is Mysterium, which she loves in part for its gorgeous, surreal cards that have this melancholy timbre to them. You can look at the cards and be inspired, even outside of the game. So I thought: What about instead of dice and all the rules that govern them, you have a deck of beautiful cards, maybe a little macabre, but also inspiring? It’s always very simple to determine success or failure in Negocios, as easy as Candyland. If your card matches one of the cards on your character sheet, success. If it doesn’t, not success! And everything else you just get to make up.” – Cultureslate Interview, Carlos Hernandez quoted

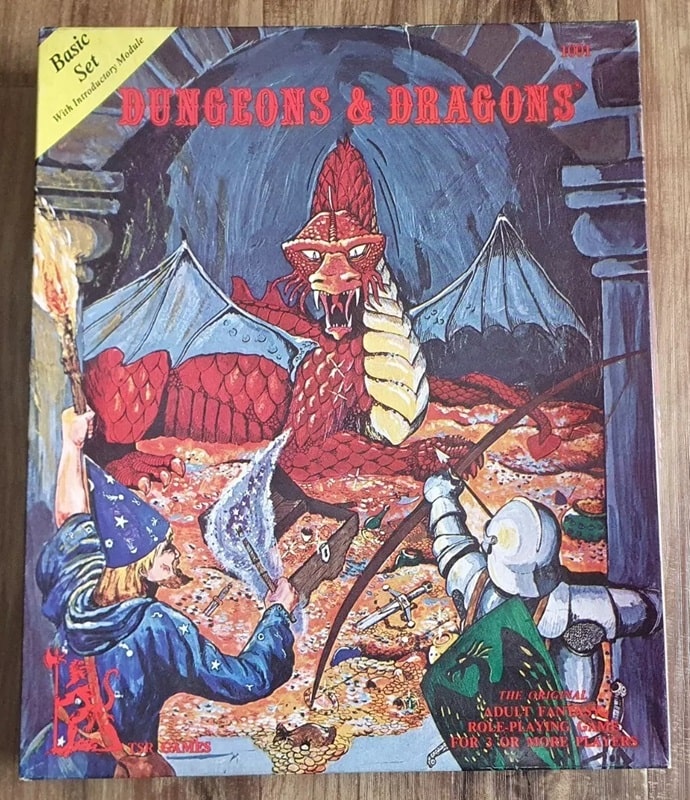

TIGER OF THE GODS: Co-designing a narrative game was a wild departure from my personal normal. And I’m so grateful that Carlos nudged me in that direction, because it opened up the whole world of gaming to me — board games, TTRPGs, and video games!

Carlos is a game designer, and when we first got together, he said I was perfect, I was MORE than perfect; maybe my only flaws were that I don’t like coffee and I don’t really play games.

Dear Black Gate Readers, I now like espresso. Okay, just a little bit of an espresso—¡un pocito espressito!—once every few months, but I can honestly say I like it.

And now, I also like games. But I didn’t always. In fact, I liked board games much better than TTRPGs when we first started playing together, for all that I’m an actor and a writer, and by my nature should be a shoe-in for roleplaying games. But I’d sort of had a “meh” view of TTRPGs, due to some less than stellar experiences, so Carlos suggested we design one together that I’d actually like.

We designed a game that has some moving pieces and some timed elements (like a board game), that’s big on character creation and world building and plot development, that’s easy for beginners, but also incredibly rich for experienced players. It’s so much fun, and so weird, and so moving.

Negocios Infernales’s tag line is: “The Spanish Inquisition… INTERRUPTED by aliens!”

Imagine a fantasy world — Gloriana — much like Earth (Gloriana’s more of a superplanet that’s mostly water, and it has two suns, but bear with me here). Now imagine a country called “Espada”—Spanish for “blade” — which is a lot like our Spain in the 15th century. The queen, Reina Resoluta, is about to sign religious persecution into law. Then… benevolent, enlightened aliens intervene! They offer cosmic powers in exchange for a zero-genocide policy on Espada.

Of course, the Espadans mistake the aliens for devils (because their deelie boppers look like horns), and while they do strike a deal for “magic powers,” they think their bargain is an infernal one.

So you play a “wizard” with “magical powers,” certain that you’ll be damned for all time for it. It is a game of cosmic irony.

One of the best things about it is our “Deck of Destiny.” It’s a 70-card oracle deck, and it’s our main mechanic for character creation, world-building, magic checks, inspiration, all of that.

But separate from the roleplaying game, we use the Deck of Destiny to run what we call “Infernal Salons,” where we invite writers and artists of every stripe to pull a card prompt or three. We set a timer. Everyone writes something, no matter what form it takes. And then, whoever wants to, shares aloud. This creates such fantastic, generative, creative nights. Many published stories and poems have come out of these salons, both for Carlos and myself, and also for many of the people who’ve participated. The “Infernal Salons may be my favorite thing that has come from designing this game.

Negocios Infernales is available for pre-order right now from Outland Entertainment, and should be in our backers’ hands in a few months — if the International Shipping gods are kind.

C. S. E. CooneyC. S. E. Cooney (she/her) is a two-time World Fantasy Award-winning author: for novel Saint Death’s Daughter, and collection Bone Swans, Stories. Other work includes The Twice-Drowned Saint, Dark Breakers, and Desdemona and the Deep. Forthcoming in 2025 is Saint Death’s Herald, second in the Saint Death Series. As a voice actor, Cooney has narrated over 120 audiobooks, and short fiction for podcasts like Uncanny Magazine, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Tales to Terrify, and Podcastle. In March 2023, she produced her collaborative sci-fi musical, Ballads from a Distant Star, at New York City’s Arts on Site. (Find her music at Bandcamp under Brimstone Rhine.) Forthcoming from Outland Entertainment is the GM-less TTRPG Negocios Infernales (“the Spanish Inquisition… INTERRUPTED by aliens!”), co-designed with her husband, writer and game-designer Carlos Hernandez. Find her website and Substack newsletter via her Linktree or try “csecooney” on various social media platforms.

Other Weird and Beautiful Interviews #Weird Beauty Interviews on Black Gate:

Other Weird and Beautiful Interviews #Weird Beauty Interviews on Black Gate:

- Darrel Schweitzer THE BEAUTY IN HORROR AND SADNESS: AN INTERVIEW WITH DARRELL SCHWEITZER 2018

- Sebastian Jones THE BEAUTY IN LIFE AND DEATH: AN INTERVIEW WITH SEBASTIAN JONES 2018

- Charles Gramlich THE BEAUTIFUL AND THE REPELLENT: AN INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES A. GRAMLICH 2019

- Anna Smith Spark DISGUST AND DESIRE: AN INTERVIEW WITH ANNA SMITH SPARK 2019

- Carol Berg ACCESSIBLE DARK FANTASY: AN INTERVIEW WITH CAROL BERG 2019

- Byron Leavitt GOD, DARKNESS, & WONDER: AN INTERVIEW WITH BYRON LEAVITT 2021

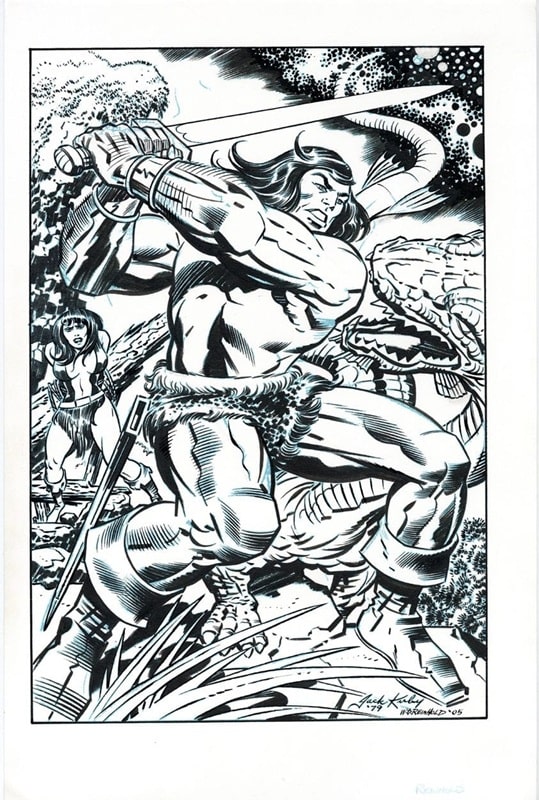

- Philip Emery THE AESTHETICS OF SWORD & SORCERY: AN INTERVIEW WITH PHILIP EMERY 2021

- C. Dean Andersson DEAN ANDERSSON TRIBUTE INTERVIEW AND TOUR GUIDE OF HEL: BLOODSONG AND FREEDOM! (2021 repost of 2014)

- Jason Ray Carney SUBLIME, CRUEL BEAUTY: AN INTERVIEW WITH JASON RAY CARNEY(2021)

- Stephen Leigh IMMORTAL MUSE BY STEPHEN LEIGH: REVIEW, INTERVIEW, AND PRELUDE TO A SECRET CHAPTER(2021)

- John C. Hocking BEAUTIFUL PLAGUES: AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN C. HOCKING (2022)

- Matt Stern BEAUTIFUL AND REPULSIVE BUTTERFLIES: AN INTERVIEW WITH M. STERN(2022)

- Joe Bonadonna MAKING WEIRD FICTION FUN: GRILLING DORGO THE DOWSER! 2022

- C.S. Friedman. BEAUTY AND NIGHTMARES ON ALIENS WORLDS: INTERVIEWING C. S. FRIEDMAN2023

- John R Fultz BEAUTIFUL DARK WORLDS: AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN R. FULTZ(reboot of 2017 interview)

- John R Fultz, THE REVELATIONS OF ZANGBY JOHN R. FULTZ: READ THE FOREWORD AND INTERVIEW (2023)

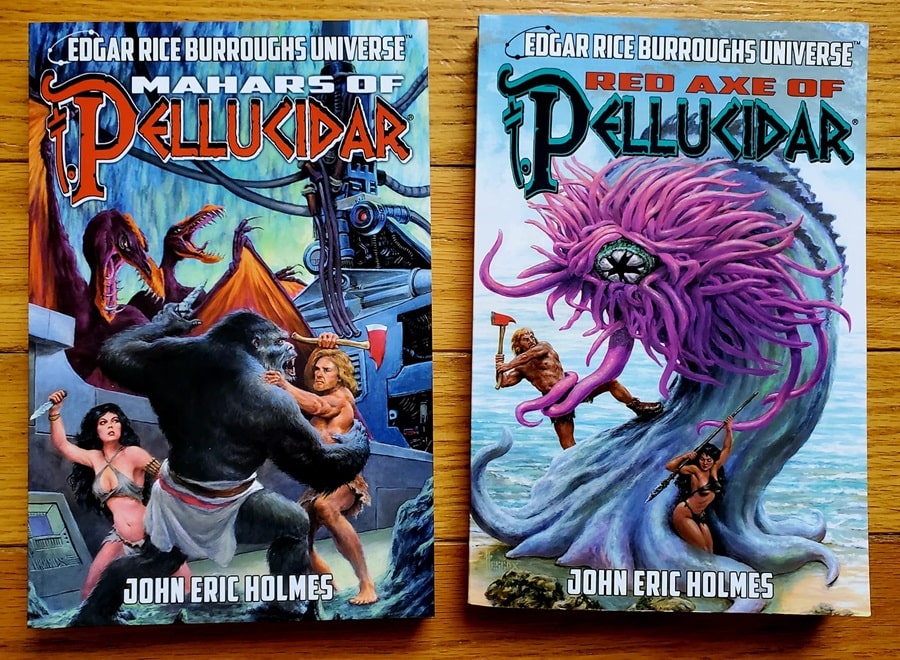

- Robert Allen Lupton (2024) https://www.blackgate.com/2024/05/26/horror-and-beauty-in-edgar-rice-burroughs-work-an-interview-with-robert-allen-lupton/

- C.S.E. Cooney (2025) You are here!

- Interviews prior 2018 (i.e., with Janet E. Morris, Richard Lee Byers, Aliya Whitely …and many more) are on S.E. Lindberg’s website

S.E. Lindberg is a Managing Editor at Black Gate, regularly reviewing books and interviewing authors on the topic of “Beauty & Art in Weird-Fantasy Fiction.” He is also the lead moderator of the Goodreads Sword & Sorcery Group and an intern for Tales from the Magician’s Skull magazine. As for crafting stories, he has contributed eight entries across Perseid Press’s Heroes in Hell and Heroika series, and has an entry in Weirdbook Annual #3: Zombies. He independently publishes novels under the banner Dyscrasia Fiction; short stories of Dyscrasia Fiction have appeared in Whetstone, Swords & Sorcery online magazine, Rogues In the House Podcast’s A Book of Blades Vol I and Vol II, DMR’s Terra Incognita, and the 9th issue of Tales From the Magician’s Skull.

What I’ve Been Listening To: February, 2025

I haven’t shared what I’ve been listening to, since November. How have you lasted this long??? Let’s rectify that right now, shall we?

I haven’t shared what I’ve been listening to, since November. How have you lasted this long??? Let’s rectify that right now, shall we?

ISAAC STEELE & THE FOREVER MAN – Daniel Rigby

This is the first of two originals produced by Audible as The Isaac Steele Chronicles – it’s not a print or digital book turned into an audiobook.

Rigby wrote it, and he narrates as well. He sounds a lot like Cary Elwes, which totally works for me (you want a great audiobook – Elwes’ memoir about the making of The Princess Bride, with several cast members reading their own parts, is superb).

It’s NSFW – I don’t play this one out loud in the office. I’d say ‘raunchy.’ So, take that for what it is.

Steele works for Greatest Britain’s Department of Clarification. He’s basically a police detective for the intergalactic British government. Greatest Britain is about as beloved as Britain was during the Colonial Era. Steele is never the most popular guy in the room. He also drinks, does drugs, has unresolved parental issues, and he’s not exactly a stickler for the rules. A scifi version of the hardboiled private eye trope.

He can be his own worst enemy, but there are plenty of other people, robots, and monsters, willing to make his life worse for him. He has a robotic partner, Timothy, who sulks in his tent like Achilles, after getting benched on the case. Steele is less than gracious in welcoming his new, temporary partner.

This is campy fun, without being silly. I can imagine that there are some seriously devoted fans, on board for more.

It came out in 2021, and a sequel, Isaac Steele and the Best Idea in the Universe, followed up in 2024. I’m gonna listen to that after I finish this first one.

It came out in 2021, and a sequel, Isaac Steele and the Best Idea in the Universe, followed up in 2024. I’m gonna listen to that after I finish this first one.

Also, I listened to Larry Correia’s three-book Lost Planet Homicide series. I don’t care how you feel about him, or David Eddings, or Josh Whedon (I’m re-watching Firefly right now: man, Fox messed up with that one), or Orson Scott Card, or Neil Gaiman, or whoever. We all make our own decisions on what we watch and read (and what Eddings did hung a bit over my re-read of The Belgariad, which I still love). And the Hugos matter not a whit in my life. If you are bothered I listened to Correia, just move along, or quit reading me, or whatever. Let’s be adults.

Lost Planet Homicide is the title of the first book of the series of the same name. It’s a hardboiled cop (detective) book set in space. It’s definitely tongue-in-cheek, and I get if some people think it’s too over-the-top. But it’s intended to be, and I think it’s more homage than parody.

A colony ship went off course and ended up a thousand light years from Earth. Croatan has five mountain peaks the rise above a fatal cloud of acid that blankets the world. This is not a fun place. Corporations and criminal syndicates call the shots. Murder can be bought off usually. When it can’t, DCI Lutero Cade is called in to…gasp…actually solve the crime! If you think Chandler’s Philip Marlowe and Bay City was cynical, welcome to Five Peaks.

The stakes are epic, and the stories link together, but also stand-alone. Oliver Wyman does hardboiled PI pretty well. Good choice.

I’m a fan of Isaac Asimov’s R. Daneel Olivaw books (I wrote about them here). So, while I don’t do much scifi (which relegates me to the kiddie table at Black Gate gatherings), I don’t mind scifi cop/PI stuff. Both of these were fun listens, with different vibes.

MALIBU BURNING – Lee GoldbergI’m a huge fan of Lee Goldberg’s Monk books. I’ve also listened to all but the most recent Eve Ronin novel, and that is a terrific buddy cop series, set in Hollywood. It occasionally borders on as dark as I get (for a hardboiled fan, I’m a little squeamish), but never goes too far. Can’t wait to get to the most recent one, Dream Town.

Anywhoo, book three of his Sharpe & Walker series is coming in April. Walter Sharpe is an arson investigator, and his new partner is former US marshal Andrew Walker. And this 2023 title about central CA on fire, certainly is timely.

Lee was a terrific screenwriter. Go look up his IMDB page. He and his writing partner William Rabkin penned a couple excellent episodes for A&E’s A Nero Wolfe Mystery. But now Lee is a regular tenant on the NY Times’ best-seller list. He writes fast-paced, absorbing thrillers and crime dramas. I haven’t even managed to get around to his hit series co-written with Janet Evanovich.

I think you could pick any of his series’ (and you can never go wrong with Monk!) and be glad you did. I’m a fan of pulpster Stewart Sterling (real-name, Prentice Winchell). Which includes his Fire Marshal Pedley books (NY Harbor cop Steve Kosko is also fine ‘unconventional’ hardboiled PI). So, a current series, about an arson investigator, written by a top flight novelist, is right up my alley. Definitely recommended.

A POINT OF LAW – John Maddox RobertsBook ten of thirteen in Roberts’ fantastic SPQR series of mysteries set in Ancient Rome. I’ve talked about them here. I absolutely love these stories, and John Lee is the perfect narrator. Click on the link for more info. I have not been disappointed with a single book so far, and I am spacing out the remaining three (Roberts died last year).

He was long working on the next book in the series. I hope they decide to find somebody of quality and have them finish it (Scott Oden?). But I’m really glad I discovered these, late to the party as I was. It sparked an interest in Ancient Rome stuff again. For example, I went and read Michael Kurland’s Roman mysteries short story collection.

ROMAN BLOOD – Steven Saylor I have written about Saylor’s fictional recounting of the real-life Austin Servant Girl Annihilator. You read that, RIGHT? Saylor is best known for his Roma Sub Rosa mysteries set in…you guessed it, Ancient Rome!

I have written about Saylor’s fictional recounting of the real-life Austin Servant Girl Annihilator. You read that, RIGHT? Saylor is best known for his Roma Sub Rosa mysteries set in…you guessed it, Ancient Rome!

With the Roberts audiobooks fanning the flames; and having read Kurland’s stories: I was ready for more. Saylor was a no brainer.

He has written over a dozen books featuring Gordianus the Finder. Now, he ‘went back’ and wrote a prequel trilogy. I tried to start the first one, The Seven Wonders. Stephen Plunkett was unlistenable. It felt like he was trying to read the entire thing in a monotone. I had to quit.

However, I still wanted to give Saylor a try, so I got the first ‘proper’ Gordianus book, Roman Blood. Scott Harrison was much better as a narrator. I completed it and immediately moved on to Arms of Nemesis.

I like Gordianus. He’s not a public office holder doing official investigations, like Decius Caeceillius Metellus the younger. Gordianus is essentially a private eye. His bartering to get a bigger fee early in book two was amusing. As with most private eyes, he finds himself in peril more than once. And he ruffles important feathers.

I like the authenticity of the Roman world in Saylor’s and Roberts’ books. It really creates a vivid background. And while I love my Hammett and Nebel, the ancient world setting is pretty cool. Roman Blood taker place in 80 AD, in Rome.

I definitely recommend checking out Saylor, and Roberts, if this kind of thing appeals to you.

THE TROJAN WAR: A NEW HISTORY – Barry StraussSo, last week’s post was all about my life-long love of the Trojan War. Which is rooted in the Iliad. I listened to this non-fiction book on the topic, which got me fired up to write last week’s entry. This was a g

I am not really interested in the spate of Trojan War novels (especially the romance ones. Ugh). Though I mentioned last week, being a huge Rex Stout fan, I like The Great Legend. I’ve long intended to read some David Gemmell, and his trilogy of Trojan War novels seems like a no-brainer for that.

But I’m into the original myth, and the study of the war, and the real-life history around it.

Been awhile since I did a non-fiction book. I learned some things. It mixed content from The Iliad, with information related to it. I learned about battering rams (apparently the real ones weren’t like Grond…), sea power, the Greek city-states: just lots of interesting info. And, I always like hearing about Iliad stuff.

This was a good listen, letting me revisit the Trojan War. Sitting and reading this would have been more difficult, for a couple reasons. But the audiobook totally worked.

What I’ve Been Listening To: November, 2024

What I’ve Been Listening To: Sepetember, 2024

What I’ve Been Listening To: August, 2024

What I’ve Been Listening To: July, 2024

What I’ve Been Listening To: September 2022

May I Read You This Book?

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

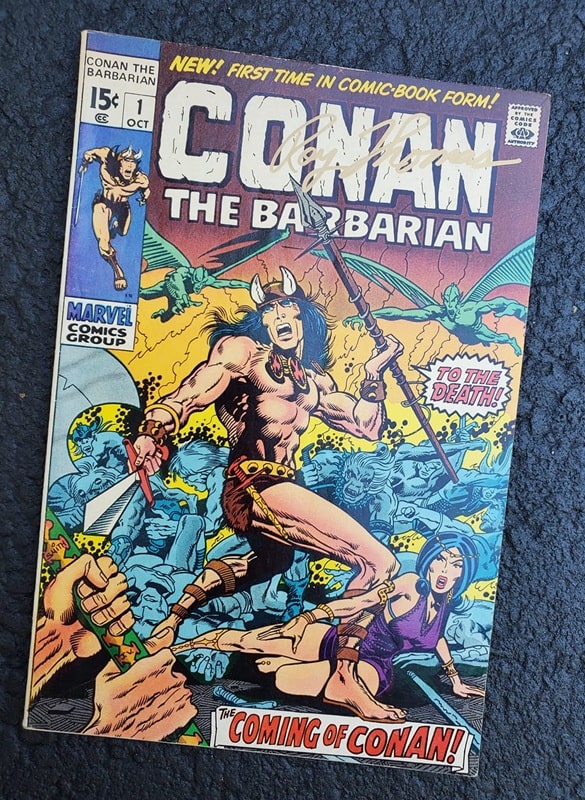

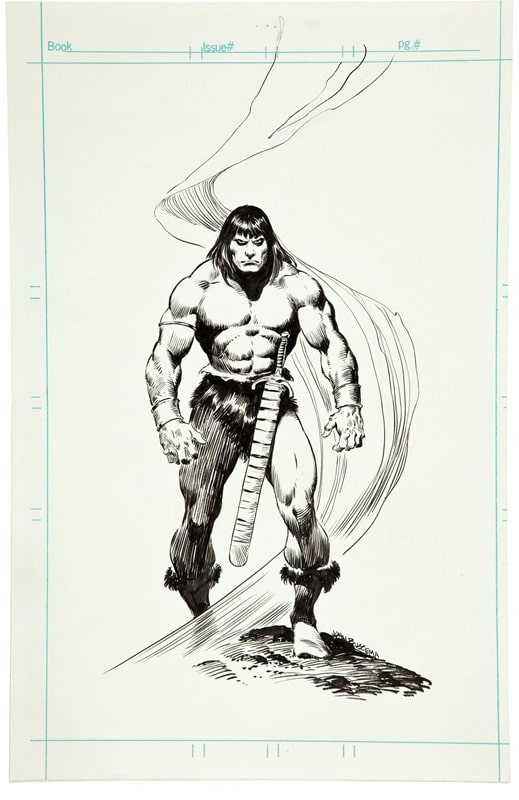

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

Alternate Londons, the Future of Lotteries, and Colony Ships: January-February Print Magazines

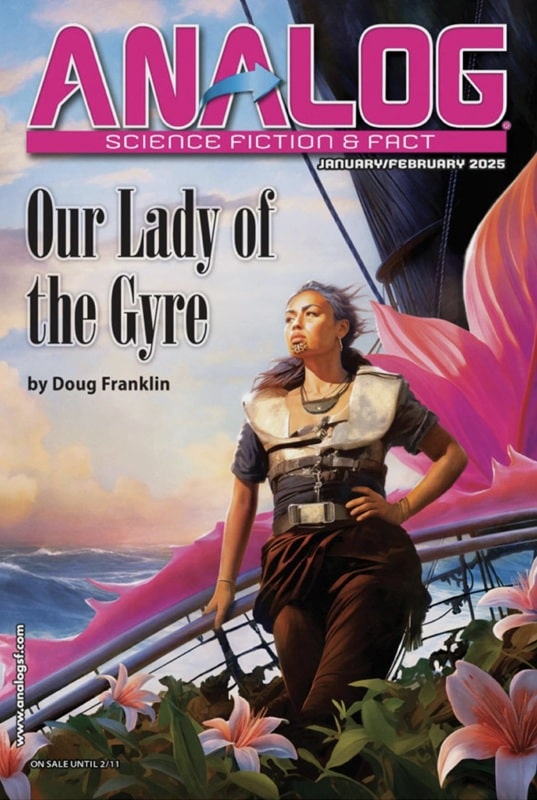

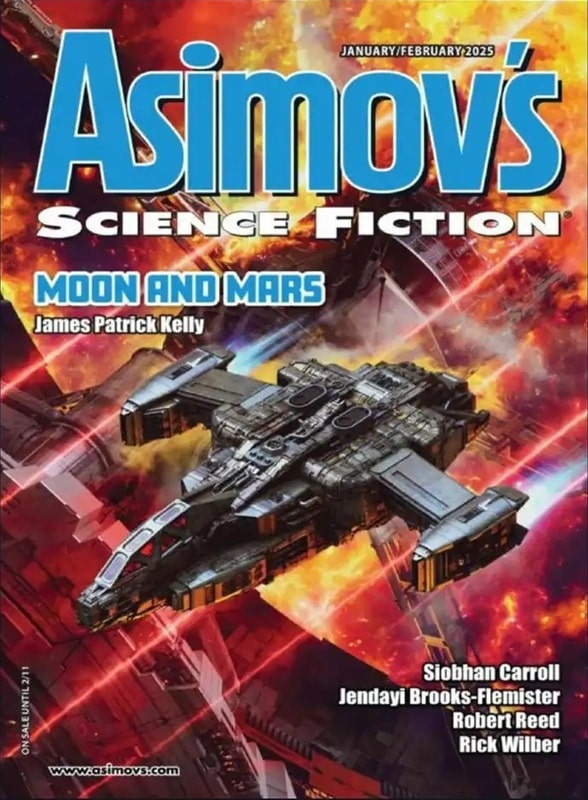

January-February 2025 issues of Analog Science Fiction & Fact and Asimov’s Science

Fiction. Cover art by Tomislav Tikulin (for “Our Lady of the Gyre”) and Shutterstock

Still no sign of the next issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, which is disheartening. That leaves us with only two issues published last year (Winter 2024 and Summer 2024), and no hint when the next one might arrive. I’m hearing rumors that the magazine has been sold, but I’ve been unable to confirm that, so for now it’s just gossip.

But we’ve got issues of Asimov’s Science Fiction and Analog Science Fiction & Fact in hand, and they’re just as enticing as usual, with contributions from John Shirley, Sean McMullen, Mark W. Teidemann, Steve Rasnic Tem, Paul Di Filippo, Sakinah Hofler, James Van Pelt, James Patrick Kelly, Siobhan Carroll, Robert Reed, Faith Merino, Matthew Kressel, Rick Wilber, Jane Yolen, Kendall Evans, and many more.

The issues contain a new Great Ship tale by Robert Reed, a new Unsettled Worlds story by Siobhan Carroll (which Sam Tomaino calls a “suspenseful, exciting tale”), a new novelette “Rejuve Blues” from John Shirley (which Victoria Silverwolf labels “a suspenseful crime story and psychological study”), and the last installment in James Patrick Kelly’s trio of stories about Marishka Volochkova, “Moon and Mars,” which Sam proclaims is “probably another Nebula nominee.”

Victoria Silverwolf at Tangent Online enjoyed in the latest Analog.

“Our Lady of the Gyre” by Doug Franklin mostly takes place aboard a sea vessel that fights excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere via bioengineered diatoms. The protagonist, who communicates with an artificial intelligence orbiting the Earth, takes two young people on his ship and faces a dangerous storm… a very dense work of fiction that requires careful reading. At first, it is difficult to tell what’s happening or what this future world is like, but patient readers will be rewarded with a vivid and imaginative tale with appealing characters.

The novelette “Rejuve Blues” by John Shirley features an elderly couple who win a lottery that offers them the chance to be young again. The man runs into trouble with criminals, while the woman, thinking he has left her, returns to her former activity as a fighter against the Taliban. The author creates a complex and convincing future that is neither utopian nor dystopian… a suspenseful crime story and psychological study.

The main character in “Go Your Own Way” by Chris Barnham accidentally discovers a way to travel into alternate versions of London, some very similar to the familiar one and others wildly different. He falls in love in one of these parallel worlds, but the arrival of an alternate version of himself causes complications. The plot is that of the eternal triangle, in which two of the people involved are the same person. (One might call it an isosceles triangle.) The various parallel Londons are described only briefly, and are far more interesting than the love story…

In the novelette “Prince of Spirals” by Sean McMullen, conspirators kidnap a forensic anthropologist and force him to study samples from the skeletons of two bodies thought to be the so-called Princes in the Tower, heirs to King Edward IV of England… The motive is to determine if either Prince survived to have descendants, giving members of the conspiracy a claim to the throne… This is a suspenseful crime story, with intriguing speculative technology and an interesting look at the techniques used by forensic anthropologists.

At first, “Quest of the Sette Comuni” by Paul Di Filippo seems like pure fantasy, as a female satyr and a golem set out to rescue a princess from a wizard, in order to free their master from his imprisonment by a sea-dwelling queen. It soon becomes clear that the golem is actually a machine and the other characters are the result of advanced biotechnology. The setting is richly imagined, from an underwater Venice inhabited by amphibious humans to an antagonist who has made himself resemble the Jabberwock from Lewis Carroll’s famous nonsense poem. Although not a comedy, the story has sufficient amount of subtle wit to draw the reader into its colorful world.

The magazine concludes with the novella “Apartment Wars” by Vera Brook. The setting is Poland in 1979. The widow of a scientist faces the possibility that she will be forced out of her relatively large apartment by the government because she lives alone. She expects her daughter and son-in-law to arrive soon as permanent guests, justifying her need for the place, but time is running out. Meanwhile, the abusive boyfriend of a neighbor threatens to expose her situation to the authorities… The situation takes a dramatic turn when the widow discovers an extraordinary device built by her husband.

Read Victoria’s complete review here.

The new Asimov’s is thoughtfully reviewed by Mina at Tangent Online. Here’s a sample.

“In the Splinterlands the Crows Fly Blind” by Siobhan Carroll takes patience to read. The world building is complex and initially confusing. The protagonist, Charlie, sets off to find his missing brother, Gabe, as well as Gabe’s girlfriend. There are some groovy invented words like Universe-shard, atmotech, Crowmind, Crowdogs and Vestigium — along with words from what seems to be a Cree dialect — they do eventually all make sense. Charlie finds himself a hero as he saves his fragment of world from destruction by the carelessness of “some rich guy stepping on butterflies.” Worth persisting.

“Five Hundred KPH Toward Heaven” by Matthew Kressel is set just after the heyday of lifts into space, reminiscent of train travel. They are being replaced by much faster, cheaper ships. In a final ascent party, Terese reminisces with other lift pilots and ponders on what is being lost — a sense of wonder and a sense of connection — “sometimes there’s benefits to going slow.”

“Shadow of Shadows” by Frank Ward is a pleasure to read because, once you reach the end, the title hits you with its full poignancy. This reader appreciates when an author does this so well. A washed-up research physicist stands at the threshold of finally finding proof for his theory of a “Many Worlds Interpretation.” The proof of alternate universes is, however, not without pain. A tale that explores not just quantum theory but also its emotional repercussions. I would read this twice.

The tension build-up in “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain” by Beston Barnett is incredible. One can only say: bravo! In this story, a desperate scientist, being interrogated and tortured by an AI courageously sets out to trick it into shutting down. The references to Linux, Hexspeak and ASCII are very satisfying for this linguist, for AI does indeed have its own language.

“My Biggest Fan” by Faith Merino is a creepy and ultimately sad tale. The narrator grows up seeing the same woman and hearing the same tune at regular intervals; but she is always a different age. She leaves him notes signed “your biggest fan.” When he finally understands why their trajectories keep overlapping, it’s tool late: they have become each other’s hell, as Sartre would say. Quantum particles meet stalker meet Greek tragedy.

In “Moon and Mars” by James Patrick Kelly, Moon-settler Mariska is part of the crew on the Natividad, a colonists’ ship she has joined to be with her Martian boyfriend, Elan. It soon becomes apparent that those with vested interests in the anti-matter that will power the ship through a wormhole to the Destination planet on the other side are trying to stop the mission. Mariska, her mother and Elan are all part of a group determined to take off early before the mission can be stopped. The race against time is gripping…. A great read.

Read Mina’s full review here.

Here’s all the details on the latest SF print mags.

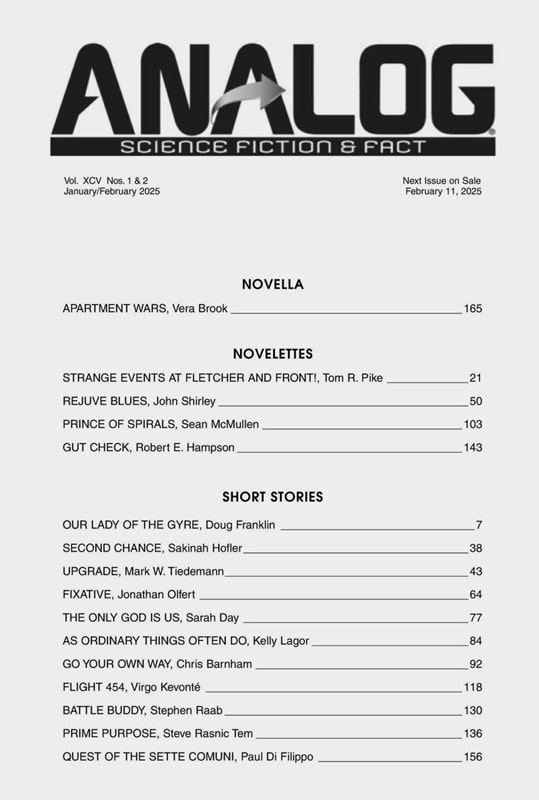

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

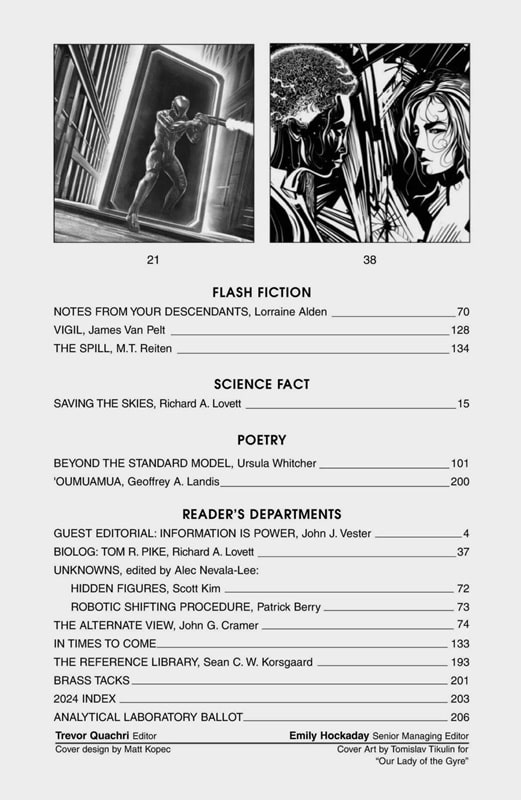

Contents of the January-February 2025 issue of Analog Science Fiction

Editor Trevor Quachri gives us a tantalizing summary of the current issue online, as usual. Sadly, I didn’t think to grab a copy before the latest issues dropped. Next time.

Here’s the full TOC.

Novella

“Apartment Wars” by Vera Brook

Novelettes

“Strange Events at Fletcher and Front!” by Tom R. Pike

“Rejuve Blues” by John Shirley

“Prince of Spirals” by Sean McMullen

“Gut Check” by Robert E. Hampson

Short Stories

“Our Lady of the Gyre” by Doug Franklin

“Second Chance” by Sakinah Hofler

“Upgrade” by Mark W. Teidemann

“Fixative” by Jonathan Olfert

“The Only God is Us” by Sarah Day

“As Ordinary Things Often Do” by Kelly Lagor

“Go Your Own Way” by Chris Barnham

“Flight 454” by Virgo Kevonté

“Battle Buddy” by Stephen Raab

“Prime Purpose” by Steve Rasnic Tem

“Quest of the Sette Comuni” by Paul Di Filippo

Flash Fiction

“Notes From Your Descendants” by Lorraine Alden

“Vigil” by James Van Pelt

“The Spill” by M.T. Reiten

Science Fact

Saving the Skies: How One Small City in Arizona is Pointing the Way to a Better (Darker) Way, by Richard A. Lovett

Poetry

Beyond the Standard Model by Ursula Whitcher

‘Oumuamua by Geoffrey A. Landis

Reader’s Departments

Guest Editorial: Information is Power by John J. Vester

Biolog: Tom R. Pike by Richard A. Lovett

Unknowns, edited by Alec Nevala-Lee:

Hidden Figures by Scott Kim

Robotic Shifting Procedure by Patrick Berry

The Alternate View by John G. Cramer

In Times to Come

The Reference Library by Sean C.W. Korsgaard

Brass Tacks

2024 Index

Upcoming Events by Anthony Lewis

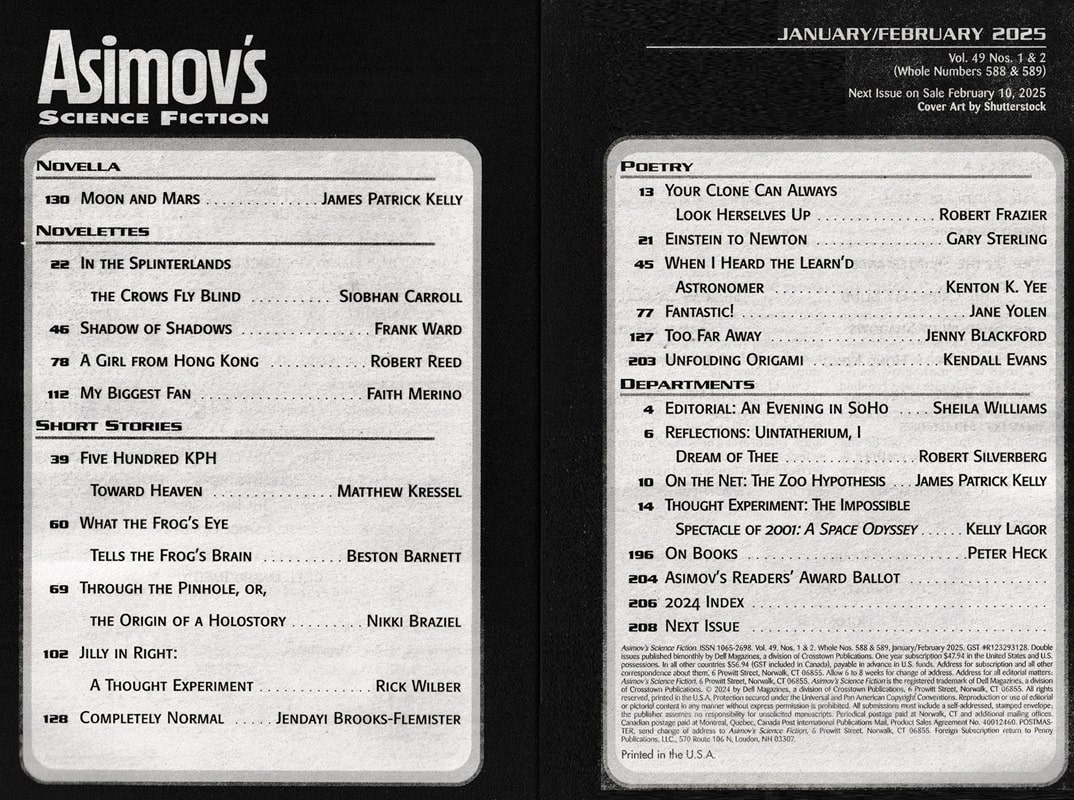

Contents of the January-February 2025 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction

Asimov’s Science Fiction

Contents of the January-February 2025 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction

Asimov’s Science Fiction

Sheila Williams provides a handy summary of the latest issue of Asimov’s at the website. But I missed it this month. Next time I’ll remember before it’s gone.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

Novella

“Moon and Mars” by James Patrick Kelly

Novelettes

“In the Splinterlands, the Crows Fly Blind” by Siobhan Carroll

“Shadow of Shadows” by Frank Ward

“A Girl from Hong Kong” by Robert Reed

“My Biggest Fan” by Faith Merino

Short Stories

“Five Hundred KPH Toward Heaven” by Matthew Kressel

“What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain” by Beston Barnett

“Through the Pinhole, Or, the Origin of a Holostory” by Nikki Braziel

“Jilly in Right: A Thought Experiment” by Rick Wilber

“Completely Normal” by Jendayi Brooks-Flemister

Poetry

Your Clone Can Always Look Herselves Up by Robert Frazier

Einstein to Newton by Gary Sterling

When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer by Kenton K. Yee

Fantastic! by Jane Yolen

Too Far Away by Jenny Blackford

Unfolding Origami by Kendall Evans

Departments

Editorial: An Evening in SoHo by Sheila Williams

Reflections: Uintatherium, I Dream of Thee by Robert Silverberg

On the Net: The Zoo Hypothesis by James Patrick Kelly

Thought Experiment: The Impossible Spectacle of 2001: A Space Odyssey by Kelly Lagor

On Books by Peter Heck

Asimov’s Readers’ Award Ballot

2024 Index

Next Issue

Analog, Asimov’s Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction are available wherever magazines are sold, and at various online outlets. Buy single issues and subscriptions at the links below.

Asimov’s Science Fiction (208 pages, $8.99 per issue, one year sub $47.97 in the US) — edited by Sheila Williams

Analog Science Fiction and Fact (208 pages, $8.99 per issue, one year sub $47.97 in the US) — edited by Trevor Quachri

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (256 pages, $10.99 per issue, one year sub $65.94 in the US) — edited by Sheree Renée Thomas

The January-February issues of Asimov’s and Analog were on sale until February 11. See our coverage of the November-December issues here, and all our recent magazine coverage here.

What a Croc, Part III

Black Water: Abyss (Altitude Film Entertainment, July 10, 2020)

Black Water: Abyss (Altitude Film Entertainment, July 10, 2020)

My next watch-a-thon is a favorite genre: crocs and gators. Unfortunately, this means the pickings are a bit slim, as I’ve already seen most of them, but I’ve managed to dig up 15 so far (supplemented with a Gila Monster and a couple of Komodos), and I’m sure the intended list of 20 will materialize as streaming services start suggesting titles.

What a Croc #14: Black Water: Abyss (2020) CrackleCroc or gator? Crocodile!

Real or faker? Some pretty great CG.

Any good? I do like me an Aussie croc flick, and this is one of them. The premise is simple: stick some folks in a cave, flood it, trap them, let loose a big croc. The spaces are tight, the tension is taut, and the croc has the good sense to eat the cast in order of character development.*

There’s a bit of relationship drama in the mix between meals, but at the end of the day it’s just a murky cocktail of Rogue and The Decent, but doesn’t come close to being as good as either. Still, I didn’t hate it, and it was well produced, so I’ll grade it a little higher.

7/10

*Now where have I seen that poster design before…?

Lake Placid: The Final Chapter (Syfy, September 29, 2012) and Rollergator (RiffTrax, 1996)

Croc or gator? Alligator(s)!

Real or faker? All terrible CG.

Any good? I still have fond memories of the first time I watched Lake Placid — I was totally unprepared for the all round brilliance of it, from the writing and the cast to the effects and direction. Sadly, each successive sequel has been horrendous, and this one, the incorrectly named ‘Final Chapter’ is the penultimate nail in the coffin.*

As you can tell from the ‘quality’ poster, the story is trite, the characters uninteresting and the effects garbage — the only redeeming features might be Robert England (hamming it up in another gator flick), and Yancy Butler (wasted here as she reprises her role as a two-pack-a-day-voiced rogue ranger). The most egregious aspect of this one though, is the directing and editing. There’s only one director who can get away with that many crash zooms, and his name is Sam Raimi.

Raimi did not direct this.

4/10

*I just discovered there are actually TWO more Lake Placid films after this one. Not that it makes this any easier.

What a Croc #16: Rollergator (1996) TubiCroc or gator? Gator. Small. Purple.

Real or faker? A hand puppet.

Any good? I tried to find the original version of this, but had to settle for the Rifftrax version. Shocking admission: I don’t find Rifftrax particularly funny (not a huge fan of MST3K either) and they just paved the way for stuff like CinemaSins and every other armchair critic who thinks they’re funny. I am fully aware of the staggering hypocrisy of this statement, but there you go.

Anyway, in this film a roller skating woman meets a small, jive talking gator and tries to get him out of the carnival and back to the swamp. Presumably written by a third-grader, it’s utter crap. Not even funny or surreal enough to be a guilty pleasure — just a miserable, miserable slog.

1/10

Mega Shark vs. Crocosaurus (The Asylum, December 21, 2010)

What a Croc #17: Mega Shark vs. Crocosaurus (2010) YouTube

Mega Shark vs. Crocosaurus (The Asylum, December 21, 2010)

What a Croc #17: Mega Shark vs. Crocosaurus (2010) YouTube

Croc or gator? Croc. Osaurus.

Real or faker? Rubbish CG.

Any good? You know what the answer is going to be, so let’s just cut to the chase. Robert Picardo is a fine actor, he voiced the male, culturally-obsessed alien in Joe Dante’s Explorers and I love him for that. He’s also good in everything else, but I guess he needed a new deck, because he’s in this.

Gary Stretch is also in this. British boxing fans may remember the name, the rest of you will just know him as a punching bag-faced enigma with the looks of a leading man and the mystery of a Swiffer. Sarah Lieving stars opposite him as a potentially badass special investigator who is relegated to scowling boobily at the rest of the cast while flying a pretend helicopter.

The story is rote, the direction and editing are dull and the effects are tragic. The titular creatures (especially the giant croc) are rendered in spectacular blur-o-vision, unhindered by weight or physics. I feel neither joy nor despair at having watched this film, I’m just languishing in a limbo populated by cookie cutters, tight vests and pixels.

4/10

Croczilla (Beijing Enlight Pictures, 2012) and Crocodile (Lions Gate, August 26, 2000)

Croc or gator? Crocodile. Big boi.

Real or faker? Fairly decent CG (in parts).

Any good? I started watching this one quite early on in the watch-a-thon, and thought it had promise, so saved it to end on a high note. It is indeed fun, however, I would sorely love to see a subtitled version, as the English dubbing on this Chinese movie is horrendous.

Promoted as China’s ‘first monster movie’, a claim that has been made on several of the films I’ve watched from China, Croczilla is meant to be a tongue-in-cheek flick. For this reason, the actors ham it up to the level of cartoon characters, and the English V.O. artists were apparently told to do the same, because the dubbing is ear-splittingly intolerable, especially the voice of Barbie Hsu’s character, which threatened to shatter every window in the house.

Aside from the audio hell, it’s a jolly romp, with a 36 ft croc on the rampage in Hangzhou, its belly full of Yuan (about a million worth, or 100,000 Euros as the shrill dubbing informs us). The cast is likeable (although the gangsters are a trifle over the top), and the croc itself is a nice bit of CG. It’s a great model, and for the most part animated well, but some of the interactions with its environment weren’t great. Overall, I enjoyed it, and that’s what matters, so there.

7/10

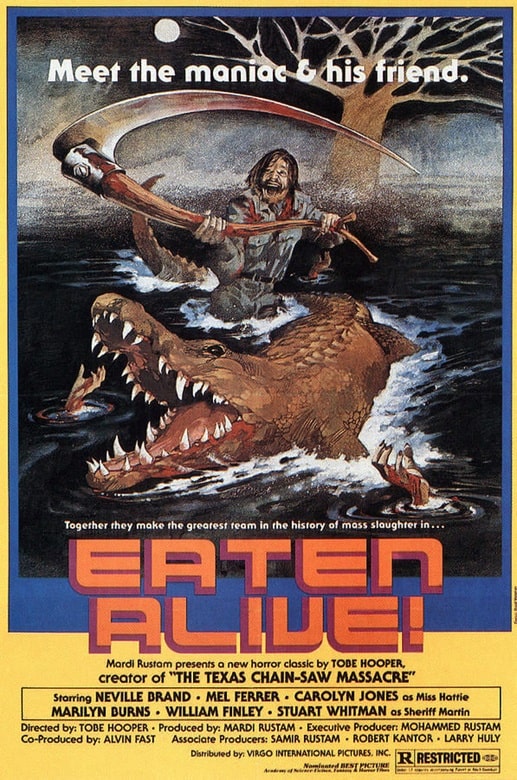

What a Croc #19: Crocodile (2000) CrackleCroc or gator? Crocodile.

Real or faker? Some OK animatronics and rubbish CG.

Any good? Apparently, when I said Eaten Alive was the only Tobe Hooper film I hadn’t seen, I had forgotten about this one — and I wish it had remained forgotten. I was initially excited when I saw Hooper’s name, doubly so when I saw the effects were done by Nicotero and Berger, but it seems there was no budget for effects and Hooper couldn’t give two shits about the film.

Nobody brings anything fresh to the production, it’s the same tired old story of unlikeable frat kids getting drunk and horny in a swamp, and the only reason to watch is to see how they get dispatched. Unfortunately, save for a couple of fun shots of folks sliding down a gullet, it’s all a bit ham-fisted, and the CG croc suffers from the same weightlessness as all the other low-budget beasts of the era. A shame.

5/10

Crocodile 2: Death Swamp (Nu Image Films, August 1, 2002)

What a Croc #20: Crocodile 2: Death Swamp (2002) Crackle

Crocodile 2: Death Swamp (Nu Image Films, August 1, 2002)

What a Croc #20: Crocodile 2: Death Swamp (2002) Crackle

Croc or gator? Crocodile. Again.

Real or faker? Some pretty great animatronics.

Any good? Hot on the heels of the disappointment of Crocodile comes Crocodile 2, which chose to ignore sequel conventions and be titled Crocodiles. Also surprisingly, it is that rare breed, the superior sequel, and I had a lot of fun with it.

No hackneyed ‘hot kids in a swamp’ plot, this one is full of bank robberies, plane crashes and helicopter hijinks. The bad guys are extremely potty-mouthed and awful enough to cheer when they get eaten, and the plucky protagonists put up a fair fight. The effects are actually pretty gruesome, and the croc itself is one of the better ones I’ve seen. Good heavens, I do believe I’ve ended on a high note!

8/10

That’s the crocs and gators done. Next up, werewolves!

Previous Murkey Movie surveys from Neil Baker include:

What a Croc, Part I

What a Croc, Part II

Prehistrionics

Jumping the Shark

Alien Overlords

Biggus Footus

I Like Big Bugs and I Cannot Lie

The Weird, Weird West

Warrior Women Watch-a-thon

Neil Baker’s last article for us was What a Croc, Part II. Neil spends his days watching dodgy movies, most of them terrible, in the hope that you might be inspired to watch them too. He is often asked why he doesn’t watch ‘proper’ films, and he honestly doesn’t have a good answer. He is an author, illustrator, outdoor educator and owner of April Moon Books (AprilMoonBooks.com).

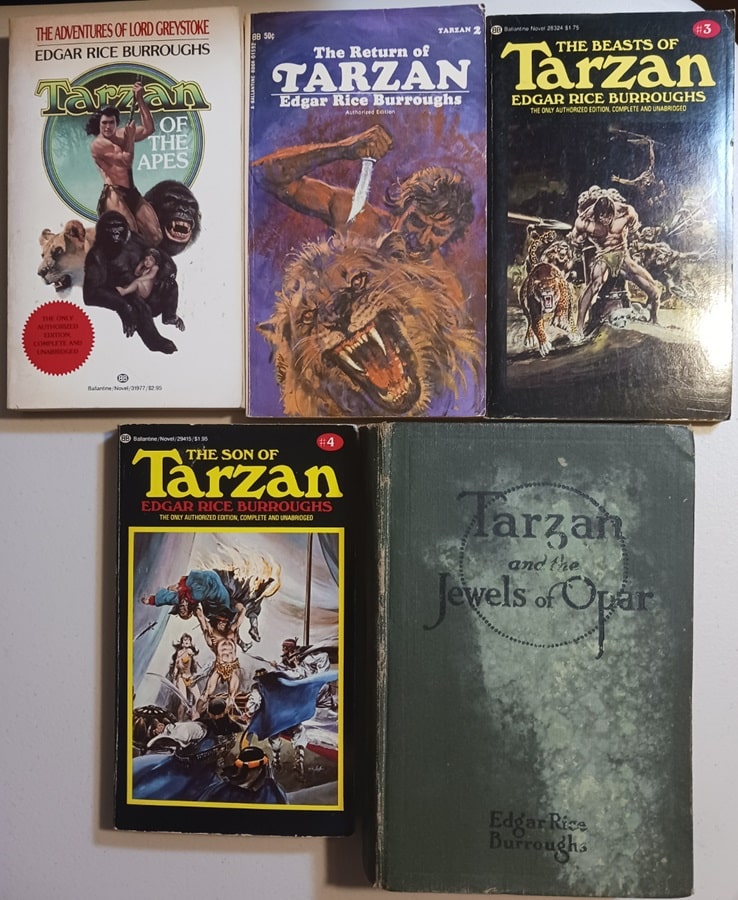

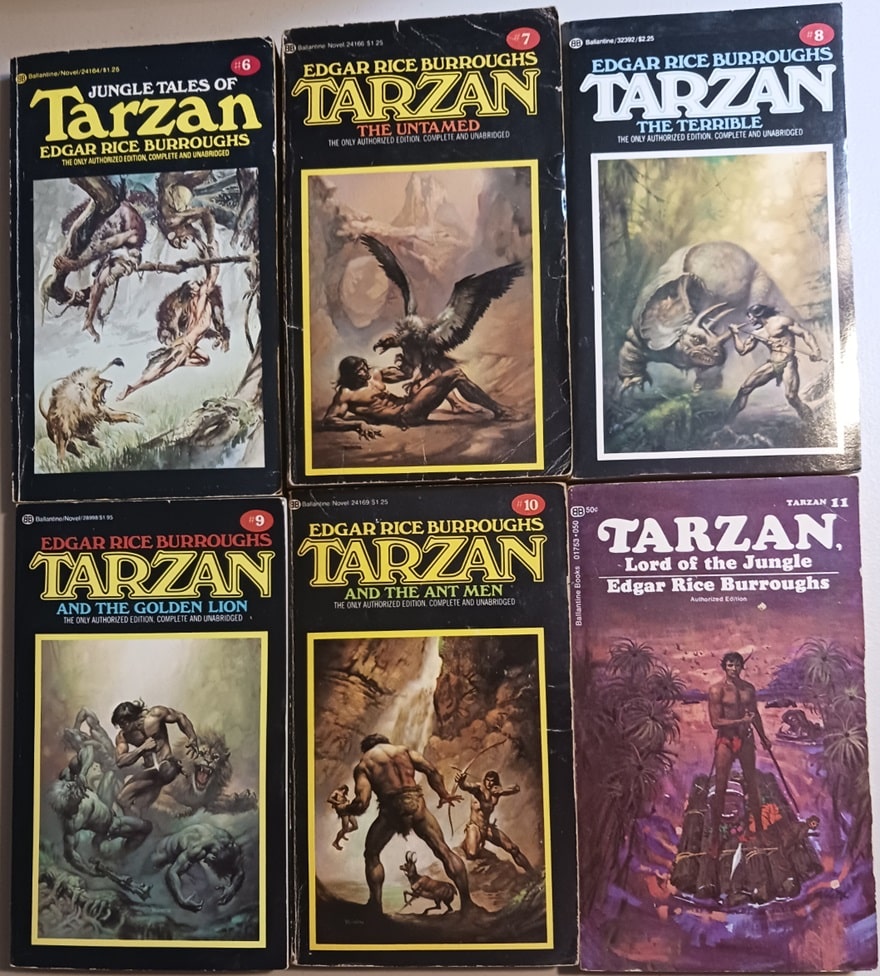

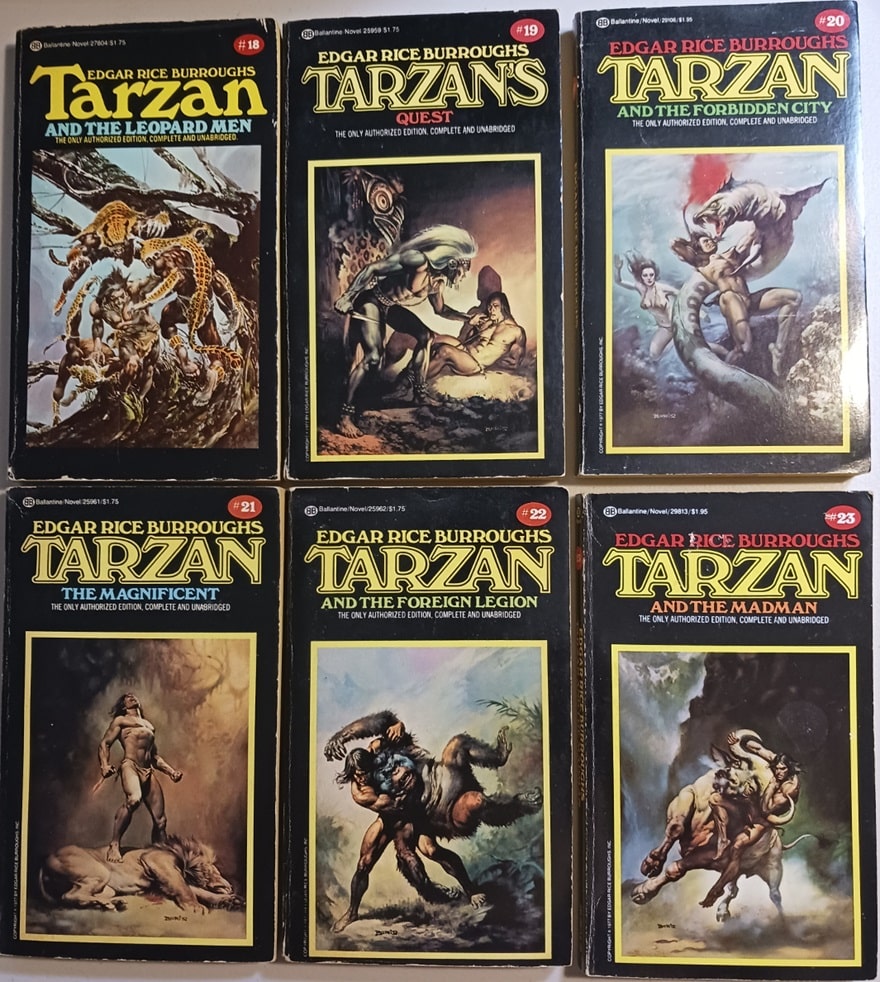

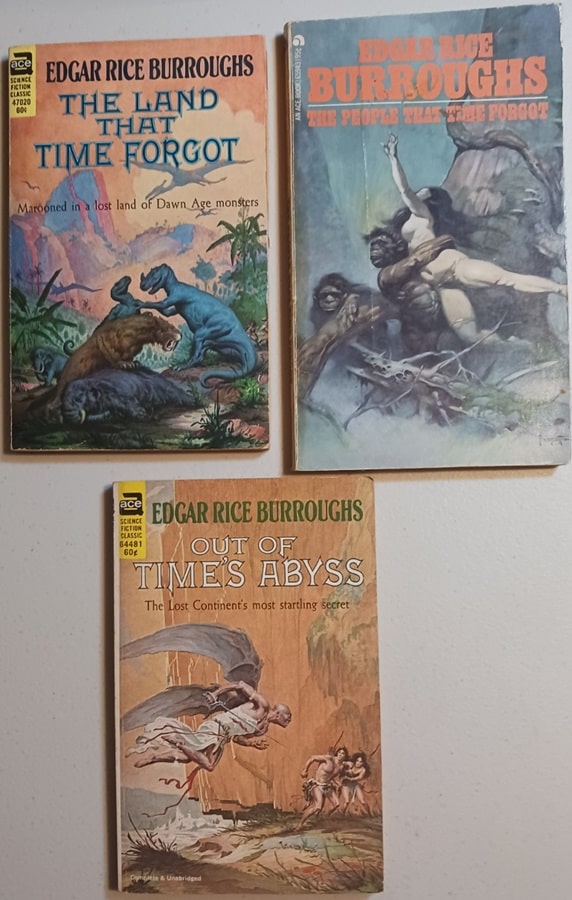

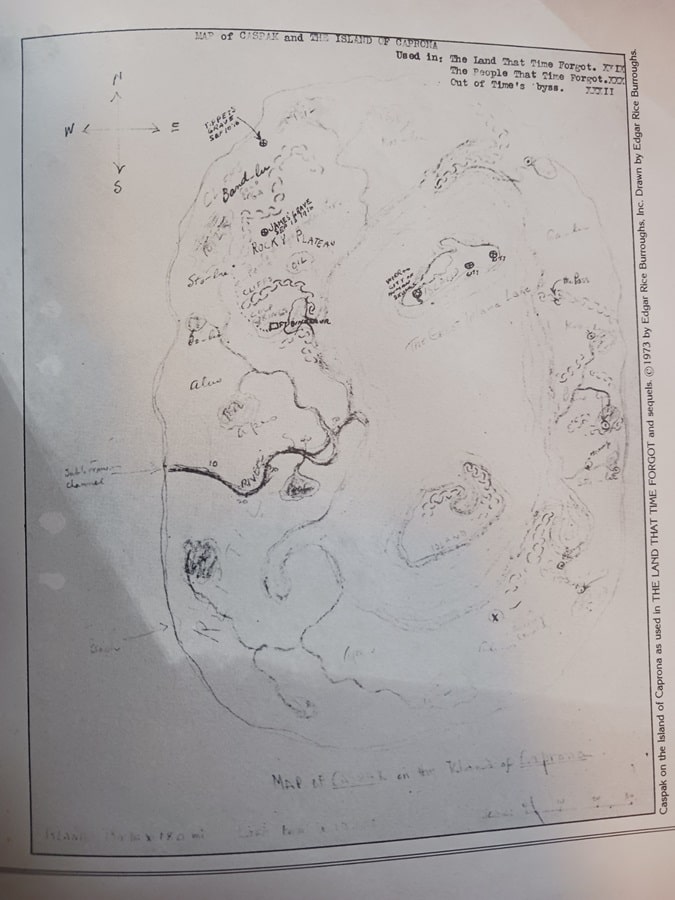

The Fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Part III: The Westerns and The Mucker

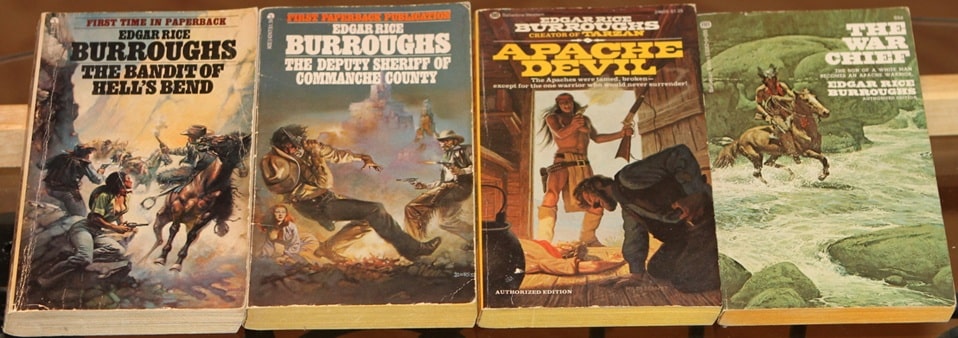

Westerns by Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Bandit of Hell’s Bend and The Deputy Sheriff of Commanche County (Ace Books); Apache Devil and The War Chief (Ballantine Books). Covers by Boris Vallejo, the Brothers Hildebrandt, and Frank McCarthy.

Westerns by Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Bandit of Hell’s Bend and The Deputy Sheriff of Commanche County (Ace Books); Apache Devil and The War Chief (Ballantine Books). Covers by Boris Vallejo, the Brothers Hildebrandt, and Frank McCarthy.

Like many pulp writers of his day, ERB dipped his toes into the western genre. He wrote four: two pretty standard ones and two that incorporate the Native American experience. He knew something of what he wrote, having worked on his brother’s ranch in Idaho at age 16, and having served with the 7th cavalry in Arizona in the late 1890s.

His first standard western was The Bandit of Hell’s Bend (1924), followed by The Deputy Sheriff of Commanche County in 1940. Both of my copies are later printings from Ace with very cool Boris illustrations. I like these better than many of Boris’s paintings because they seem less static. He does a good job of portraying action here.

In Bandit, we have a disgraced ranch foreman and a young woman who has inherited the ranch, and various villains who want to steal the ranch from her because they know there’s silver on it. The foreman, Bull, has to rise to the occasion. There’s great action and pretty good plotting, although you’ll probably figure it out pretty soon. And, as always, ERB creates sympathetic heroes and dastardly villains.

In Deputy Sheriff, a cowboy named Buck Mason is suspected of a murder he didn’t commit, and he has to run and hide until he has a chance to prove his innocence. This plot is not as good as Bandit but it gets the job done to showcase ERB’s lightning paced tale.

ERB’s other two westerns are connected and center very strongly on the Native American experience. The hero, though, is a white boy who is taken captive by Apaches and raised as Geronimo’s adopted son. He is given the Apache name of Shoz-Dijiji (Black Bear), for having killed one at a young age, and he grows up hating whites.

These books are The War Chief (1927), and Apache Devil (1933). Although there are some stereotypical elements to these books, they show that ERB had very strong sympathies for the Apache and disapproved of the way they had been treated by whites.

I found all of these books well worth reading, though the Apache books have stayed with me the longest. The cover art for The War Chief is magnificent and is by Frank McCarthy. The Apache Devil cover looks to be signed by Hildebrandt.

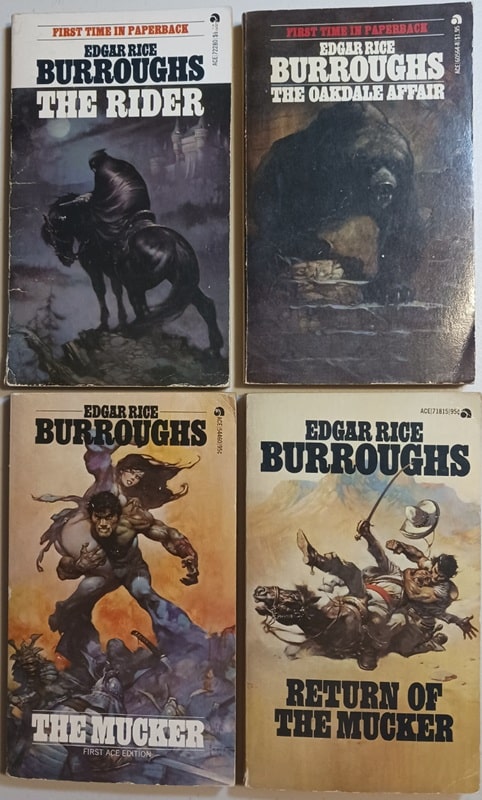

The Rider, The Oakdale Affair, The Mucker, and Return of the Mucker (Ace Books). Covers by Frank Frazetta.

The Rider, The Oakdale Affair, The Mucker, and Return of the Mucker (Ace Books). Covers by Frank Frazetta.

ERB wrote a three book series generally called The Mucker. They were first published in magazines in the mid to late 1910s, but I have much later reprints, of course, from the 1970s. All of mine, shown here, are from Ace books with Frazetta covers. I particularly like the first book cover, although all are cool.

The Mucker (1914). Billy Byrne is born on the mean streets of Chicago and grows up a criminal. After being accused of murder, he flees to San Francisco and ends up shanghaied. A shipwreck leaves him and a beautiful high society girl stranded in an east Asian jungle and she needs rescuing. I really liked the development of the character here. Through love, Billy learns how to be a decent human being and becomes quite a hero.

The Return of the Mucker (1916). This book finds Billy trying to clear himself of his previous murder charges and failing. He ends up in Mexico in the midst of a revolution. And it so happens that his love interest from the first book, Barbara, is also there. The Mucker was a very fine novel but the sequel is pretty weak. Coincidences pile upon coincidences until it’s pretty hard to suspend belief. But it still has the action rolling. This one could easily be counted as one of his westerns given the setting.

The Oakdale Affair (1918). I’m not sure what ERB was striving for with this book. It’s got mystery elements, gothic elements, horror elements, western type elements. He put everything and the kitchen sink into this one. But it worked and I enjoyed it. It is only peripherally related to the Mucker stories in that it features a hobo character that appeared in The Return of the Mucker.

I included ERB’s The Rider here because of the Frazetta cover and because it was at one point published in a double with The Oakdale Affair. But it’s not part of the Mucker series. It involves a bandit called “The Rider” who exchanges places with a prince (Boris) who is about to be married to the princess of another European duchy (neither of whom want to marry the other). Chaos ensues. ERB crammed a lot of action and plot twists into this short work.

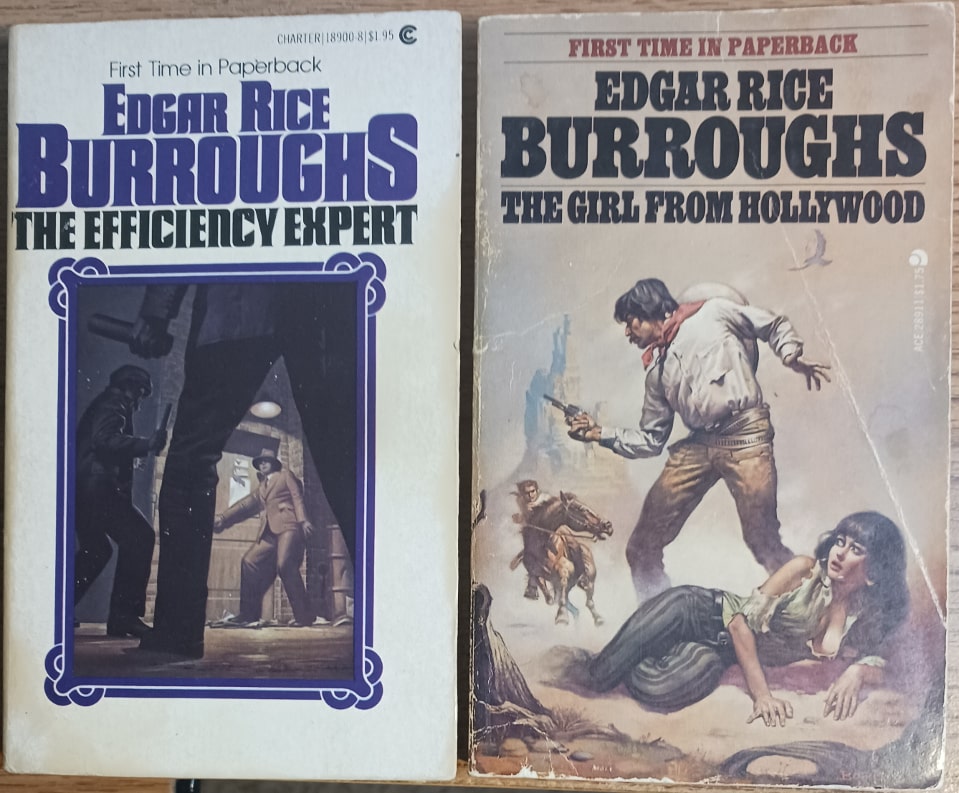

The Efficiency Expert (Charter, 1979) and The Girl From Hollywood (Ace Books, 1977). Covers by John Rush and Boris Vallejo

The Efficiency Expert (Charter, 1979) and The Girl From Hollywood (Ace Books, 1977). Covers by John Rush and Boris Vallejo

My favorite genres are Fantasy, SF, Westerns, Horror, and Thrillers. I don’t read a lot of straight mysteries and read relatively little “mundane” fiction. By mundane, I mean fiction set in a modern world where the happenings are portrayed as realistic. After reading ERB’s westerns and everything he wrote with fantastic elements, I was left with three books: The Girl from Hollywood, The Efficiency Expert, and The Girl From Farris’s.

They were also among the more difficult ERB books to find and were expensive, but I wanted them because they were… well, ERB. I got both Girl and Efficiency in 1970’s paperback form but couldn’t get Farris and finally ordered it in a modern paperback printed from public domain materials. Here are my capsule reviews.

The Girl from Hollywood (ACE, 1977, Boris Cover) is not quite a western. It takes place in the 1920s, but much is set in a western landscape and involves many western tropes. The plot involves a fine western family whose lives become entangled with Hollywood types. Some of these are basically good and recover from their evil natures while others never do.

As is typical of ERB’s work, there are coincidences that help the plot along, and there’s actually very little action compared to his typical story. However, the sheer narrative drive that ERB was able to bring to his tales keeps you reading. I finished it in one day, if not quite one sitting. Not my favorite work by him by far, but still enjoyable.

The Girl from Farris’s (CreateSpace edition, 2017). Cover by Frank Frazetta

The Girl from Farris’s (CreateSpace edition, 2017). Cover by Frank Frazetta

The Girl from Farris’s (Public Domain, from CreateSpace, 2017). The cover is by Frank Frazetta. An editorial note names Taylor Anderson as editor, and claims the publisher is Odin’s Library Classics. The text appears to be intact but the print is small and there are no indented paragraphs. I actually read this in ebook version, though, so I’ll just stick it on my shelves. I rather like the cover but don’t know where it came from.

“Farris’s” is a house of ill repute and June Lathrop a lady of the evening who is trying to escape it. She meets a young man — Ogden Secor — who wants to help her and fate keeps throwing them together. It’s a tale of redemption, which is an element in all three of these novels. One particularly interesting point is that Ogden is a failed Chicago businessman who tries to make a new life for himself in Idaho. ERB himself fled the business world of Chicago for his brother’s Idaho ranch. They say, “write what you know.”

The Efficiency Expert (Charter, 1979, cover by John Rush) is the last Burroughs book I’ve read, and very nearly the last one to exist that I hadn’t read. I left these three to last thinking they weren’t much up my alley. None of them have any fantastic elements. Efficiency Expert is a straightforward and realistically based story of a young man of quality who is down on his luck but never succumbs to corruption and wins out in the end. I was engrossed throughout. There’s certainly plenty of coincidence featured in the plot but I didn’t mind it much and even without a lot of action happening, it had narrative drive and kept my attention.

I’d rate Efficiency the best of the three, followed by Hollywood and Farris’s.

We’ll wrap up Burroughs next time with a look at his Hollow Earth tales.

Previous installments in this series include:

The Fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Part I: Sword and Planet

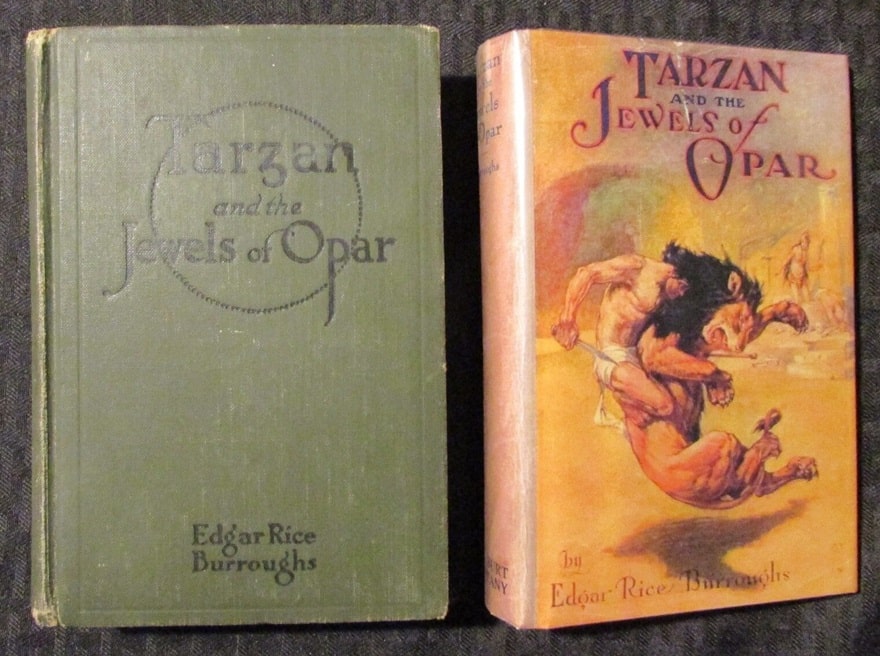

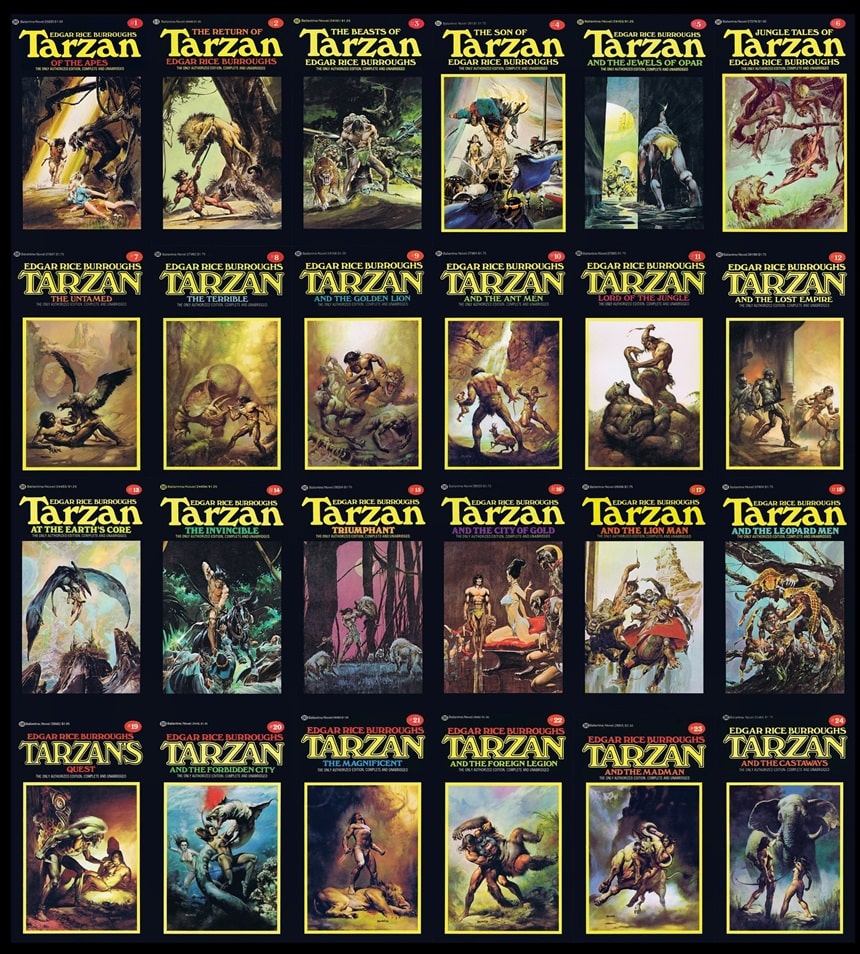

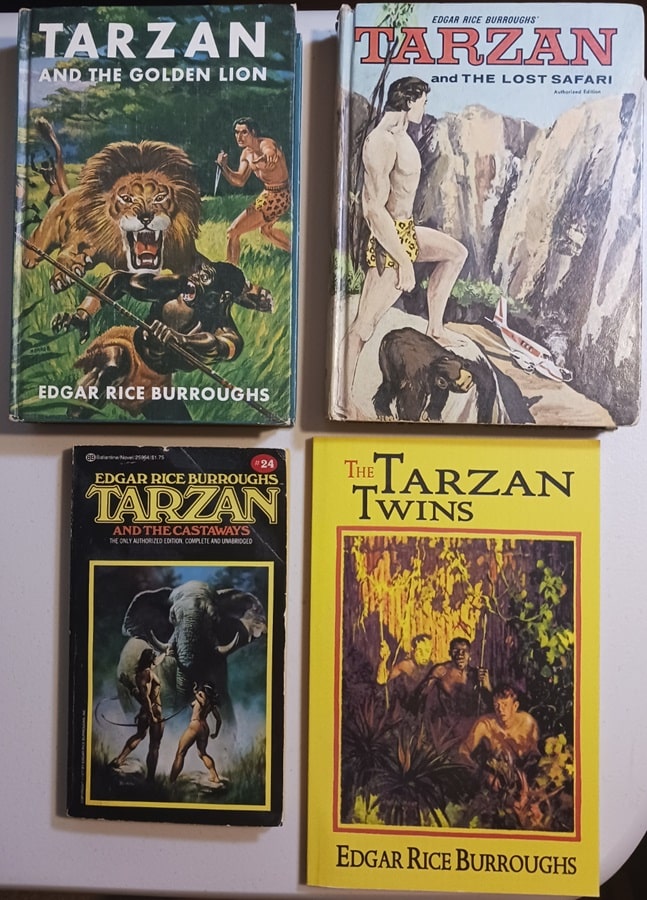

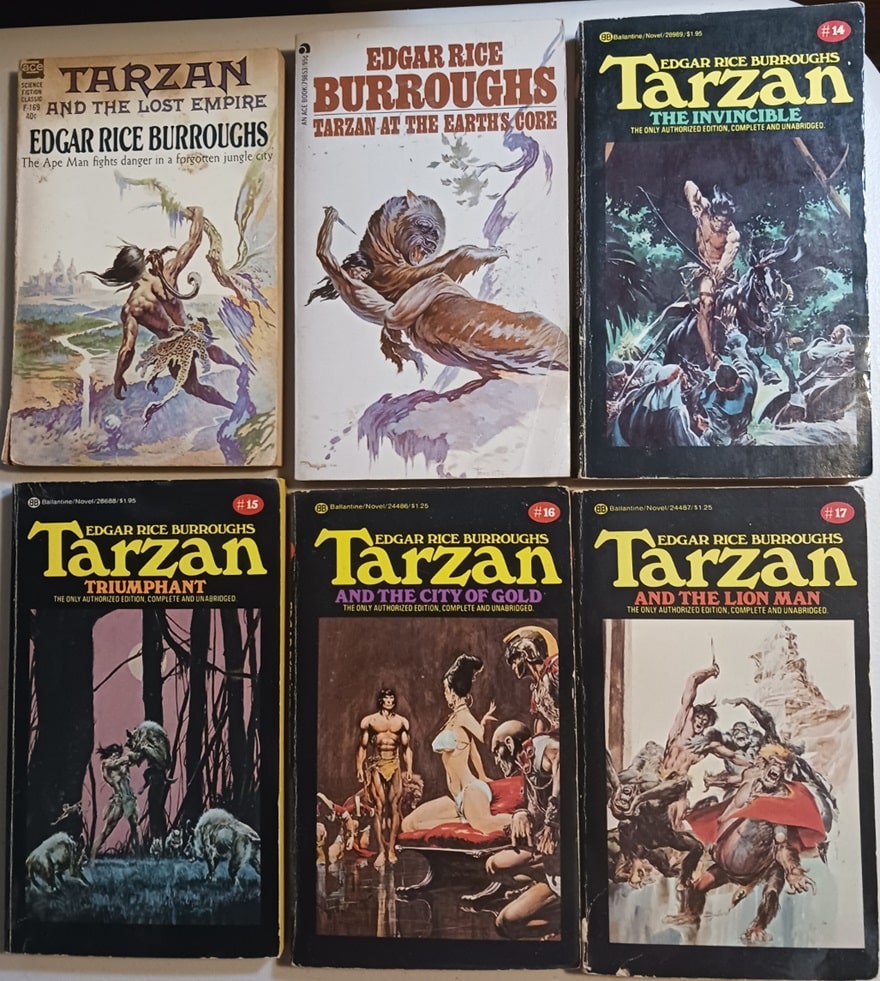

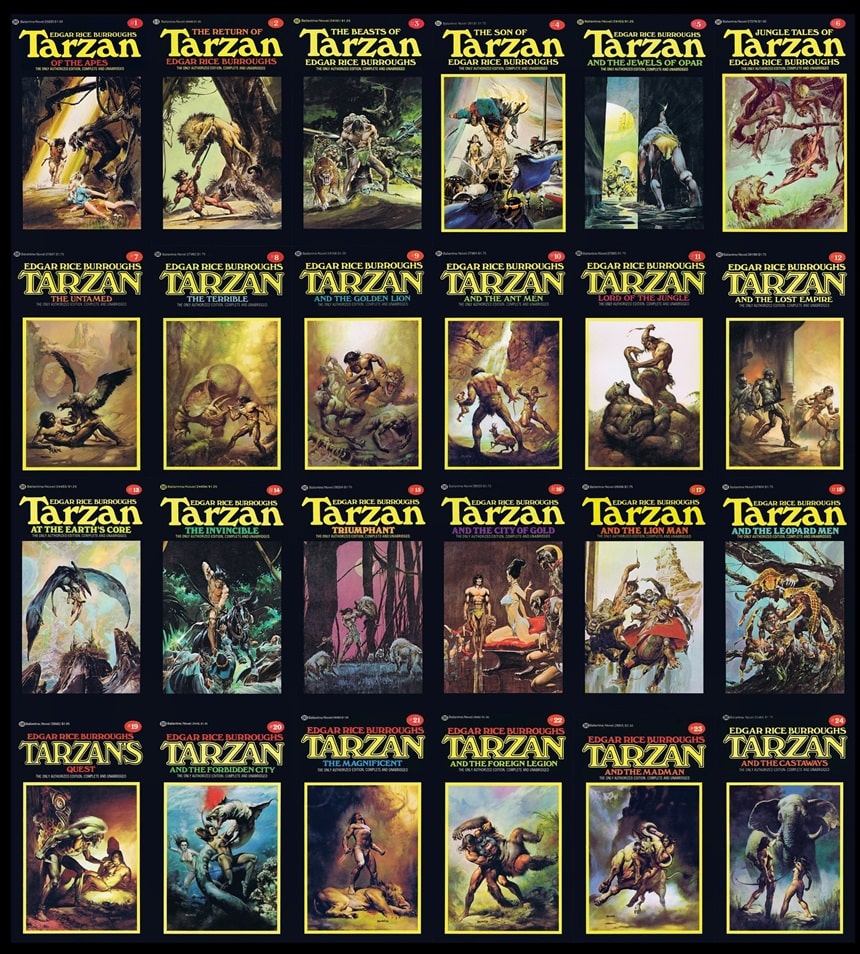

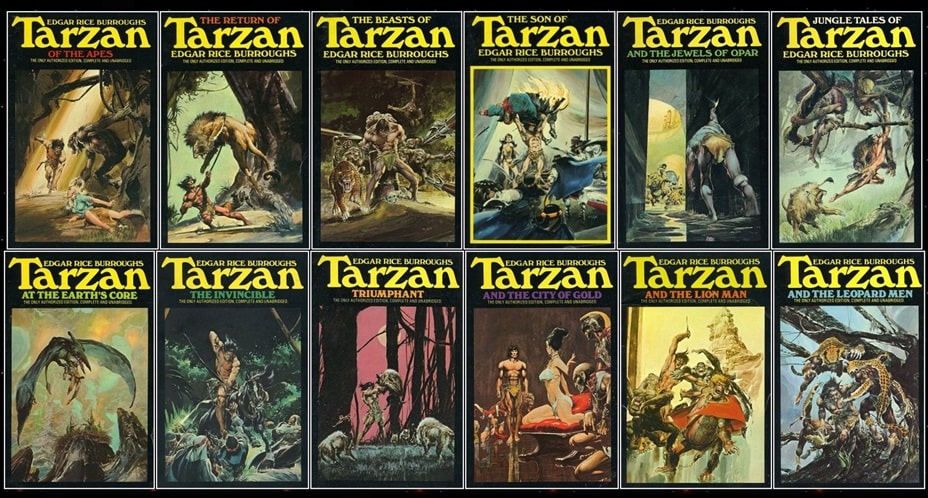

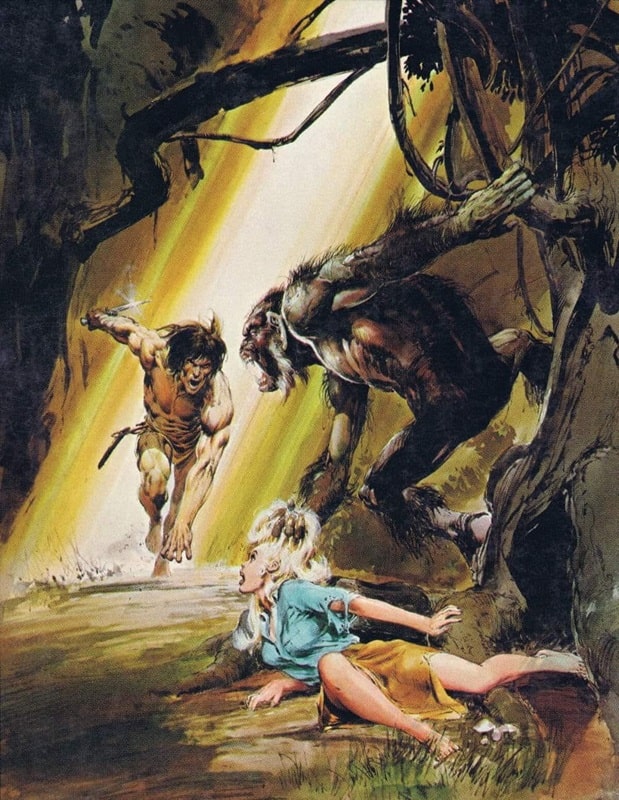

The Fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Part II: Tarzan and The Land That Time Forgot

Charles Gramlich administers The Swords & Planet League group on Facebook, where this post first appeared. His last article for Black Gate was The Fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Part II: Tarzan and The Land That Time Forgot.

Goth Chick News: (Another) Throwback Thursday – Johnny Depp, Roman Polanski, and The Club Dumas

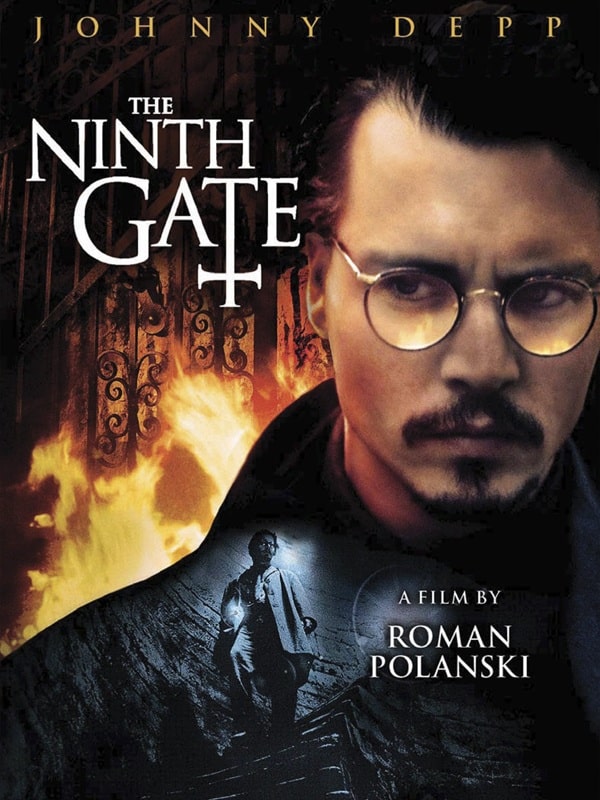

The Ninth Gate (Summit Entertainment, 1999)

The Ninth Gate (Summit Entertainment, 1999)

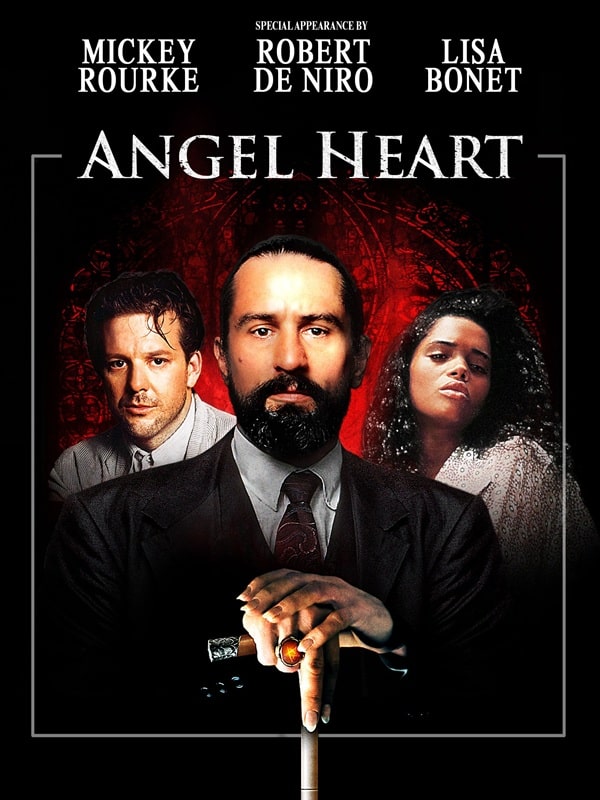

Last week’s article on Angel Heart not only resulted in a lot of fun and insightful comments from all of you, but it got me thinking about another film that I appreciate in a similar way. It will be twenty-six years old next month and having given it a re-watch last weekend, I wondered what your thoughts would be on this one.

The Ninth Gate, directed by Roman Polanski and starring Johnny Depp, was released in March 1999. Polanski was co-writer on the screenplay which was loosely (and I do mean loosely) adapted from the book, The Club Dumas (1993) by Arturo Pérez-Reverte.

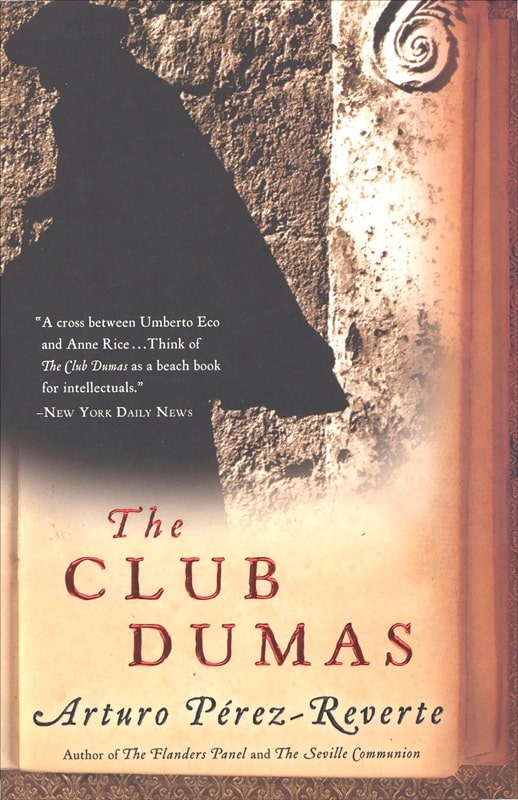

The Club Dumas by Arturo Pérez-Reverte (HarperVia, May 1, 2006)

The Club Dumas by Arturo Pérez-Reverte (HarperVia, May 1, 2006)

In the film, Dean Corso (Depp) is a New York book dealer with a reputation for unscrupulous methods. When Boris Balkan (Frank Langella), a wealthy collector of rare books on the occult, hires him to authenticate a mysterious tome called The Nine Gates of the Kingdom of Shadows, Corso embarks on a journey across Europe.

The book, rumored to summon the devil when used correctly, exists in three copies, but only one is authentic. Corso’s task is to examine the three editions and uncover the truth. As Corso delves deeper into his investigation, strange deaths and supernatural occurrences begin to haunt his steps. Along the way, he is joined by a mysterious woman (Emmanuelle Seigner), whose true nature seems tied to the book’s sinister secrets.

In parallel with Angel Heart, The Ninth Gate presents a dark journey into the unknown by a skeptical protagonist who is in over his head but doesn’t know it. The memorable visuals created by Darius Khondji, who is known for his work on Se7en, are well synchronized with the puzzle elements of the story and Polanski’s signature direction is evident as well. From dusty bookstores to candlelit castles, the cinematography oozes occult suspense all over the place.

I frankly love The Ninth Gate all the way up until its final few moments.

[Minor spoilers ahead.]

The film does a fabulous slow burn to what can only be described as an enigmatic conclusion, and this is why Angel Heart is still my favorite of the two films. While we aren’t at all confused as to what will become of Harry Angel, The Ninth Gate leaves viewers in the maddening position of wondering whether Dean Corso has unlocked forbidden knowledge, become ensnared in a deadly conspiracy, or gone to literal Hell – maybe all three. I remember screaming “NO!” at the screen when the credits rolled since all the fabulous creepiness that built through the entire film, simply went off a cliff at the very end, without resolution.

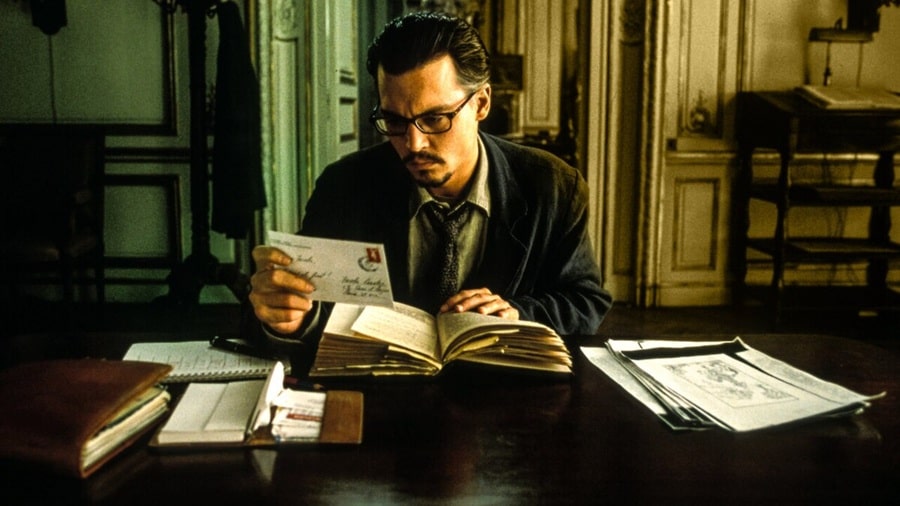

Johnny Depp in The Ninth Gate

Johnny Depp in The Ninth Gate

That sent me straight to the source material to see if Polanski was being a jerk by leaving us with such an unsatisfactory conclusion. I immediately went out and bought a copy of The Club Dumas assuming that it would fill in some, if not all, of the missing pieces.

Nope.

While The Ninth Gate is based on The Club Dumas, it omits substantial portions of the novel, particularly a subplot about a lost chapter of The Three Musketeers. The film focuses solely on the occult storyline, which, by the way, is a sub, SUB plot of the book. If anything, the ending of the book was even more obtuse, with themes centered on literary puzzles and human obsession rather than a definitive supernatural climax.

Interestingly, the titular tome at the center of the film, called De Umbrarum Regni Novem Portis, or The Nine Gates of the Kingdom of Shadows, is a fictional text. Its design plays a significant role in the plot, with eerie and violent illustrations which are gruesomely brought to life in the form of the demise of several characters. The engravings within The Nine Gates book, which were painstakingly designed for the film, serve as the visual centerpiece of the story. Each engraving contains subtle differences across the editions, forming cryptic clues for Corso and the audience to unravel. For movie prop collectors, it is a highly recognizable and sought-after addition.

Emmanuelle Seigner and Johnny Depp in The Ninth Gate

Emmanuelle Seigner and Johnny Depp in The Ninth Gate

I used to have visions of owning my own copy of The Nine Gates, however, a well-made replica with a leather cover can go for upwards of $1200 or more. If you’re interested in a more attainable version, an engineer named Michael F. Haspil has created a detailed tutorial including the printable text and illustrations you’ll need to build one yourself, which you can find here.

Ultimately, The Ninth Gate received mixed reviews at the box office and made a rather crappy $58M against a $38M budget – so basically a bomb by Hollywood standards. Though critics praised its style, it was criticized for its pacing and lack of resolution. Despite that, The Ninth Gate has aged well with viewers like me who enjoy slow-burning mysteries and subtle horror. Depp delivers a restrained performance, grounding the fantastical story in a world of skepticism and pragmatism, while Frank Langella’s portrayal of Boris Balkan adds recognizable vice as a man consumed by his quest for power, at the peril of his soul.

The Ninth Gate’s blend of literary intrigue and supernatural tension makes it a film that (mostly) stands up over time. Whether you’re a fan of Polanski’s work, a lover of occult mysteries, or simply curious about the interplay between literature and cinema, The Ninth Gate is worth revisiting.

Thoughts?

Reading for the End of the World Redux

Eight years ago, in the wake of the 2016 election, I penned a piece for Black Gate that I called “Reading for the End of the World”, in which I listed a dozen books I thought ideal for helping us get through the four years of turmoil and uncertainty that loomed ahead. I wrote it, posted it, and moved on with my life, little suspecting that coping with that particular cultural earthquake was not a one-time job like getting a vasectomy, but would instead turn out to be an onerous recurring chore like mowing the lawn or doing the laundry.

Well, if He did it again, I suppose I should too. Therefore, once again, “In the spirit of the incipient panic, withered expectations, and rampant paranoia that seem to dominate our current national life, I offer twelve books to get you through the next four years (however long they may actually last): a reading list for the New Normal.” (Groundhog Day is a movie, not a book; that’s why it’s not here.) In 2017 I hoped that the books I discussed would provide some much-needed insight or diversion, and that’s my hope for these twelve additional volumes. Some things have changed after the passage of eight years, however, so now I suppose I should also state that these books were neither written nor selected with the help of A.I. (Of course, that just begs the larger question — how do you know that “Thomas Parker” is a real person? Short answer: you don’t. Then again, I don’t know if any of you are real people, either.)

1. All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren, 1946