https://www.blackgate.com/

The Sword & Planet Tales of Ralph Milne Farley

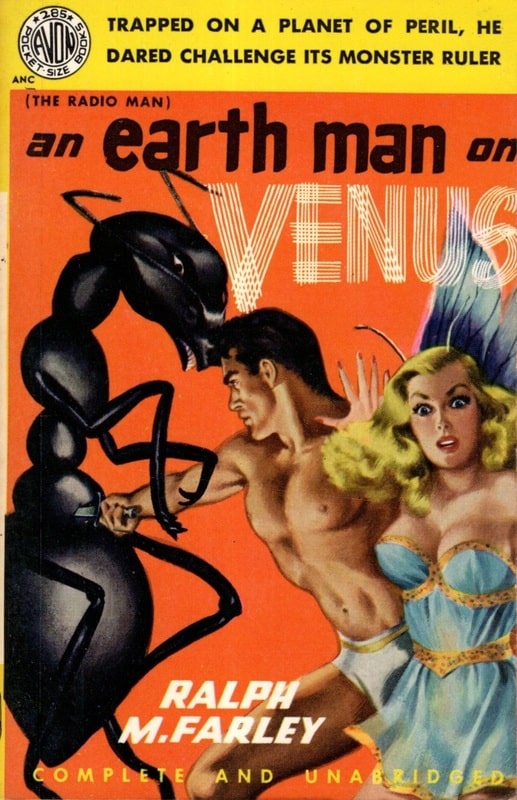

An Earthman on Venus (Avon, 1950). Cover by Raymond Johnson

Ralph Milne Farley (1887 – 1963) was a pseudonym for Roger Sherman Hoar. Hoar was a Massachusetts senator and an attorney general, so I can understand his use of a pseudonym to write his SF stories under, but I can’t imagine why he’d choose one just as long and awkward as his real name, and even less memorable.

At any rate, Farley was friends with Edgar Rice Burroughs and wrote his own series of Sword & Planet adventures sometimes called the Radio series, since most of the books featured the term radio in their titles.

[Click the images for non antmen-sized versions.]

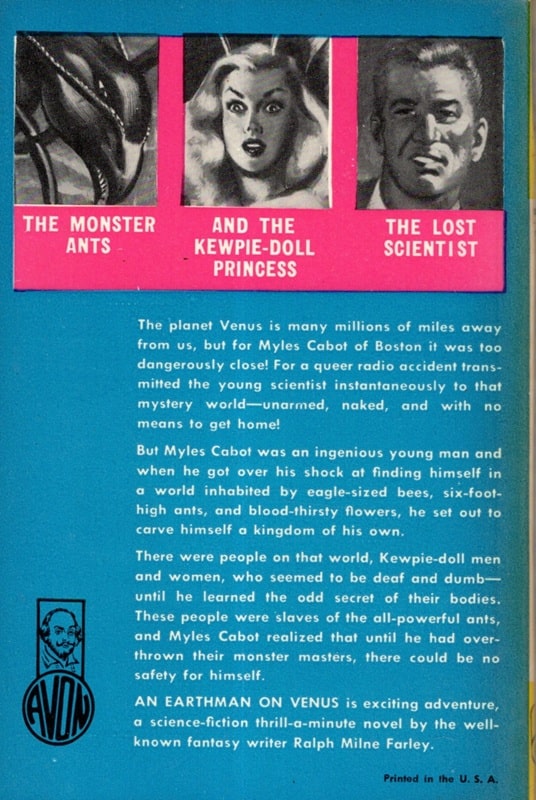

Inside cover of An Earthman on Venus

Inside cover of An Earthman on Venus

As far as I can see, there are about ten titles in this series, but I’ve only read the first two (covers shown above and below):

The Radio Man (or An Earthman on Venus): Avon Books, (Raymond Johnson cover), 1924/1950

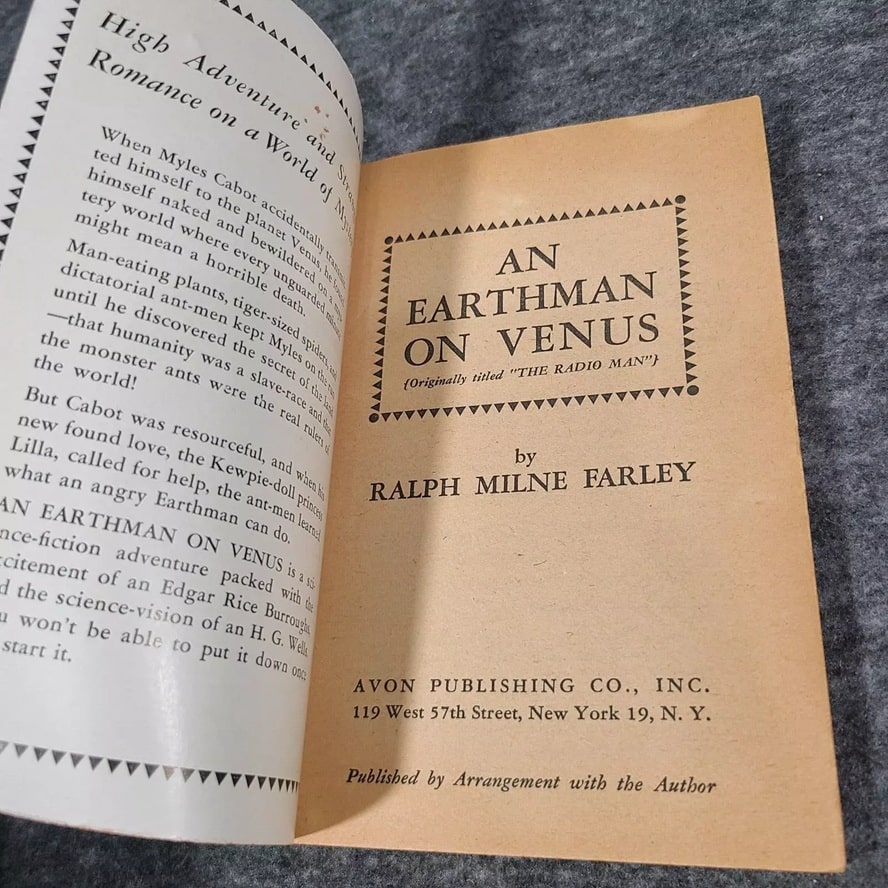

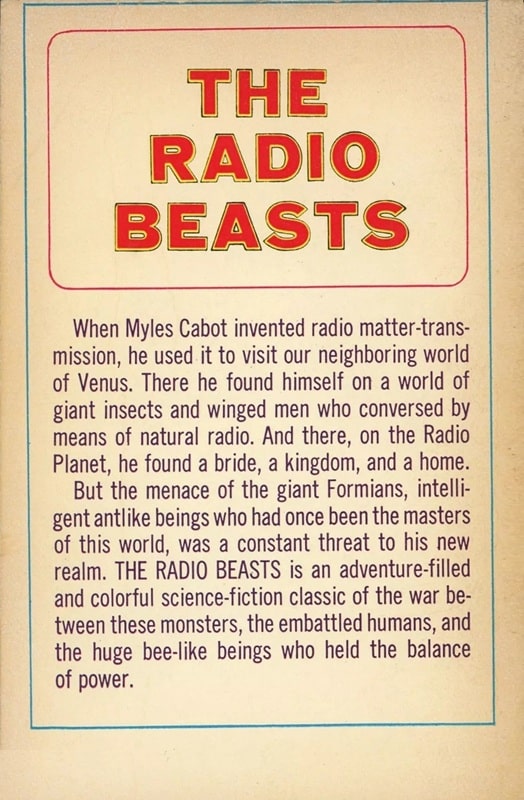

The Radio Beasts: Ace Books, (Ed Emshwiller cover), 1925/1964

In The Radio Man, an Earth scientist named Myles Cabot invents a transmission device that uses radio and accidentally transmits himself to Venus, where he finds human-like beings — including a princess — who are enslaved by intelligent, horse-sized ants who use radio waves for communication. Cabot uses his technical know how to create guns for the humans and leads a revolt.

The story was inventive and fun but without nearly as much action and derring-do as ERB’s John Carter stories.

The Radio Beasts (Ace Books, February 7, 1964). Cover by Ed Emshwiller

The sequel, The Radio Beasts, was also readable but didn’t seem to add much to the overall story, and the writing doesn’t have the flair and color of ERB.

I don’t, at present, have any intention of reading the rest of the volumes, which — as far as I’m aware — consist of:

The Radio Planet

The Radio Flyers

The Radio Gun-Runners

The Golden Planet

The Radio Menace

The Radio Man Returns

The Radio Minds of Mars

The Radio War

Charles Gramlich administers The Swords & Planet League group on Facebook, where this post first appeared. His last article for Black Gate was Of Men, Monsters, and Little People.

The Beating Heart of Science Fiction: Poul Anderson and Tau Zero

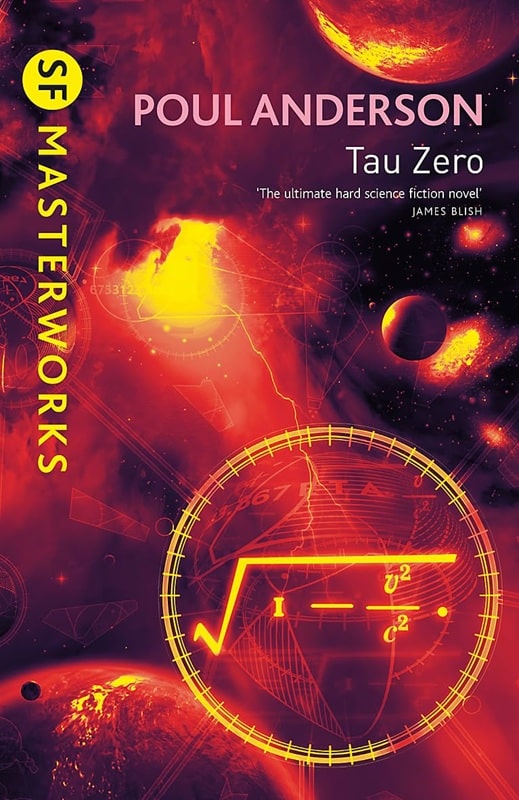

Tau Zero (Millennium/Gollancz SF Masterworks, February 2006). Cover by Dominic Harman

Tau Zero (Millennium/Gollancz SF Masterworks, February 2006). Cover by Dominic Harman

Science fiction — what is it, really? What elements place a story firmly in the genre? For any requirement that you can think of, there is probably a great sf story that violates it, and rather than cobble together some dictionary-ready definition, it’s easier to just think of particular books that you would hand to someone unacquainted with the genre with the words, “Here — read this; this is science fiction!”

Everyone would have their own choices for such a list, of course, and those choices would amount to your de facto definition. For me, some of those books would be Rendezvous with Rama by Arthur C. Clarke, The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester, and Man Plus by Frederik Pohl, but the very first book on my list would be Poul Anderson’s 1970 novel Tau Zero. Why? What does this book have that makes it a quintessential work of science fiction?

Maybe it’s this — it’s a grand voyage, a brave excursion into the great out there, and it also has a grand perspective shift, like a camera pulling back in a movie, a maneuver that radically alters everything that you had previously thought about the story, something that’s not a minor adjustment, but a move that completely explodes the frame. You think the story is this, but it’s really that, you think you’re here, but you’re really there; the here where you thought you were turns out to be the tiniest corner of there, a there that is larger and stranger and more dizzying than you ever could have originally imagined. (In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Peter Nicholls calls this kind of maneuver a “conceptual breakthrough.”)

Tau Zero begins as a straightforward story of an interstellar voyage, but it ends as far away from that prosaic beginning (prosaic by the standards of science fiction, I mean) as it is possible to imagine. Farther than that, really, and I think that’s the whole point.

Sometime in the 23rd century, the colonization ship Leonora Christine sets out from earth for a planet thirty light-years away. Unlike many stories of this type, the voyage isn’t prompted by the world coming apart at the seams; generally, things are going quite well, which is largely due to the people of the planet submitting to a global government run exclusively by… Scandinavians. Everyone just handed the reigns to the Nordic folk because of their universally acknowledged rationality, efficiency, impartiality, and lack of any pesky Will to Power. I know, I know — send any complaints to that son of Denmark, Poul Anderson. I guess he figured he would inoculate his readers against all the wildness to come by giving them the nuttiest thing first.

If the interstellar colonization mission is a stock situation, Anderson peoples it with characters that are themselves mostly recognizable types. The Leonora Christine’s Captain is Lars Telander, a solid, stolid, stoic father figure who seems ideal at the beginning of the journey, but who fades (if not wilts) into the background under the stresses of the voyage and the extraordinary emergency that the crew eventually has to deal with. More central to the life of the ship and the story Anderson tells are First Officer Ingrid Lindgren, ultra-competent while still being sensitive and sympathetic, and the book’s real protagonist, Ship’s Constable Charles Reymont, willing to be as much of an unlikable, hard-nosed SOB as necessary in order to hold the crew together and complete the mission. Reymont’s and Lindgren’s on-again, off-again romance and their consciously embraced good cop/bad cop roles form the human core of the story.

Anderson devotes significant time to this pair and to the other crew members whom they alternately coax (Lindgren) and steamroll (Reymont) on the way to their goal. In one sense, the book is a tract on the dynamics of leadership in a uniquely stressful situation, and the author had clearly thought a lot about such problems and had some definite ideas about how to deal with them.

It has to be said, however, that Anderson’s depiction of character rarely rises above a fairly rudimentary level; there’s an off-the-rack feel to most of his people. What we have here isn’t Henry James in space, and stylistically, the book wasn’t written to dazzle; if you’re looking for graceful allusiveness, poetic imagery or memorable turns of phrase, you need to look elsewhere; Anderson’s prose generally doesn’t rise above the level of “workmanlike” (which doesn’t mean that it’s bad — it usually has the far from negligible virtues of efficiency and clarity). So, old Poul is no Nabokov in space, either.

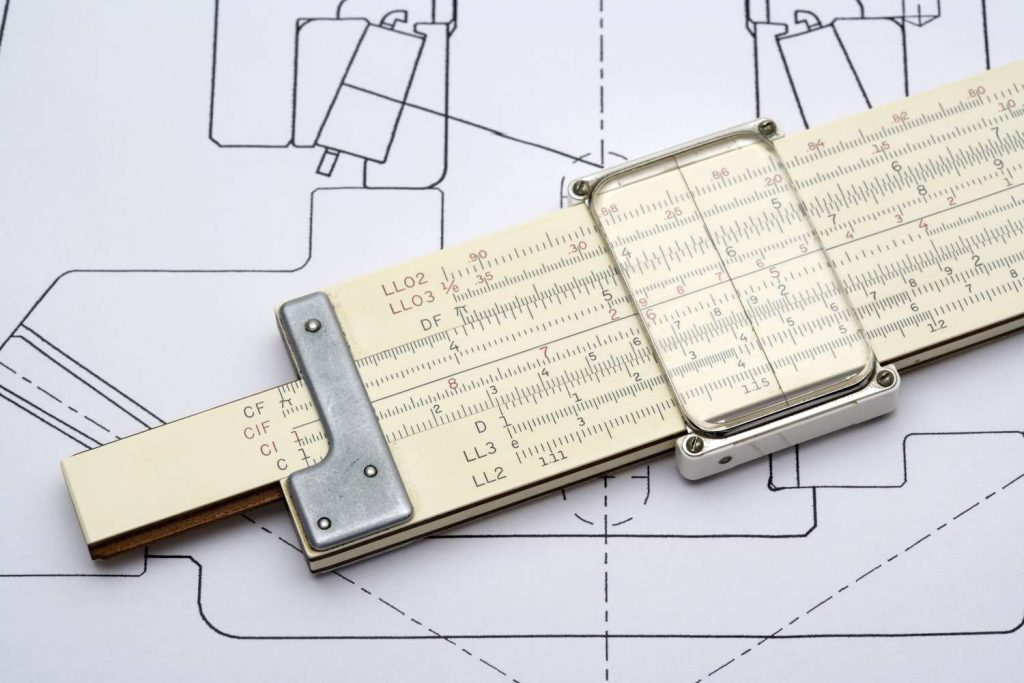

So what? Tab A in Slot B prose and slide-rule stiff characters are hard-sf traditions that go back all the way to the vacuum-busting days of Hugo Gernsback (and Anderson’s work isn’t nearly as wooden as the stuff old Hugo published), which just means that you adjust your expectations when you read this kind of sf story. (Oh, what’s a slide rule? Google it, kid.)

In the long run, Anderson’s deficiencies are perfectly acceptable because what you read Tau Zero for is the writer’s wide-screen vision and the extraordinary crisis his people face, and what a vision! What a crisis!

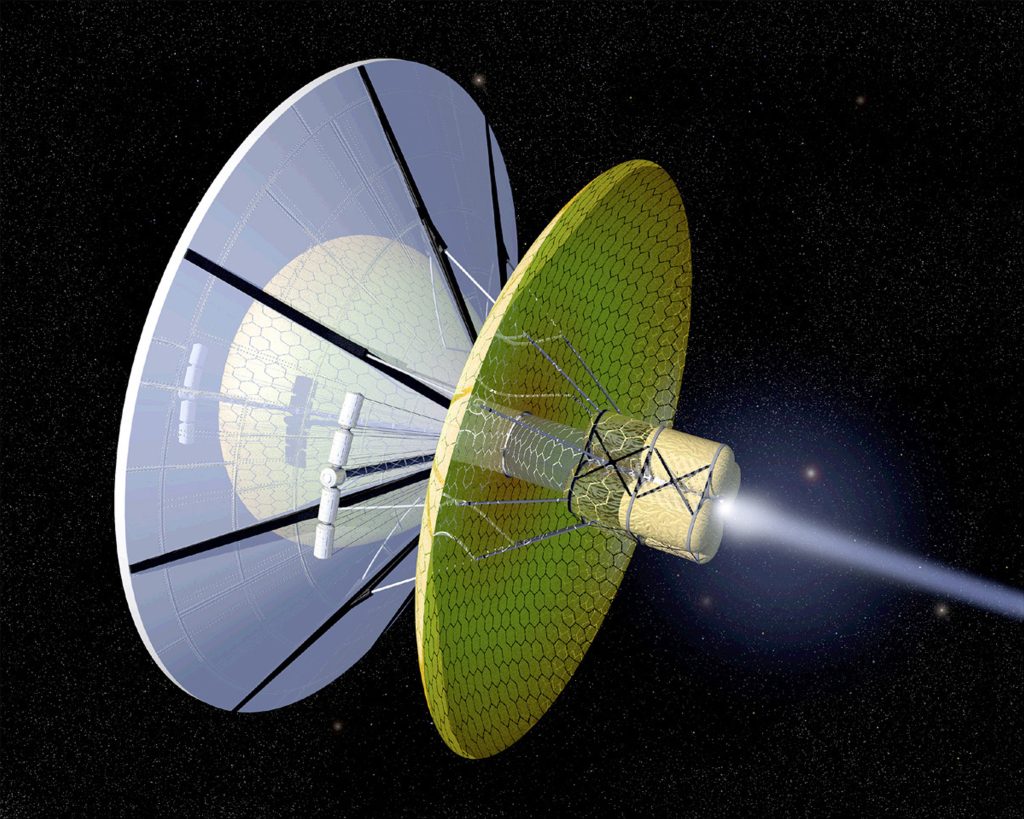

The Leonora Christine powers itself by collecting hydrogen as it travels through interstellar space and using it for fusion. (Technically this makes the ship a Bussard ramjet, though Anderson never uses the term.) As such a ship can approach the speed of light but cannot exceed it, the vessel’s flight plan is to accelerate up to near light speed during the first half of its voyage and then steadily decelerate down from that halfway point until it arrives at the target planet. Because of the relativistic time dilation caused by its extreme speeds, over thirty years will pass on earth while only five years will pass on board the ship.

Initially, things go smoothly as the crew settles into the routines that will occupy them during their long journey, and as expected, people (half of the multinational, fifty-person crew are male and half are female) begin to pair off in preparation for life as colonists on their new world. Everything seems to be going according to plan, until, before reaching the midway deceleration point, the Leonora Christine collides with an unanticipated interstellar dust cloud; because of the ship’s increased mass (due to its speed) this is potentially a very serious event, more like slamming into a brick wall than strolling through a fog bank.

At first, the ship seems to come through this emergency surprisingly well, but the truth soon becomes apparent. The collision has caused irreparable damage to one vital system — the one used for deceleration. The Leonora Christine is unable to slow down.

Why is the damage irreparable? To make repairs, it would be necessary to exit the ship, but the engines generate radiation that would be instantly fatal to anyone outside the hull, and the engines cannot be shut down because they generate an electromagnetic field which is the only thing protecting the crew from the hard radiation of galactic space. (The darn thing must not have been designed by Scandinavians.)

Reymont, Lindgren and the rest are thus faced with the prospect of an endless, pointless voyage that can only conclude with their own deaths from accident, old age or despair, sealed inside something that began as a ship, turned into a prison, and can only end as a coffin. Such an appalling situation would be bad enough, but the Leonora Christine’s crew soon comes to an even grimmer realization.

Unable to decelerate, the time dilation that was to have initially separated them from their home by a mere thirty years is only growing more extreme. The stunned crew members quickly realize that it is not decades that are passing outside the ship, not centuries, not millennia, even. “Soon”, millions, and then billions of years have passed. The would-be colonists whose aim was to open a new world for people from earth to live on must now accept that earth’s sun has long since burned to a cinder, their planet has vanished, their species has become extinct. The fifty exiles on the Leonora Christine are the last human beings alive in the universe, and unless they can find a solution to their dilemma, they are the last human beings that there will ever be.

How will they respond? Panic? Madness? Suicide? Reymont and Lindgren (especially Reymont) are resolved to hold the crew together, determined that they will all continue to do their jobs in the hope (hope being one of the defining characteristics of the late, great human race) that they will eventually find some way to slow down and locate some world, somewhere, where they can make a new start and keep their species alive.

Despite being more radically alone than any human beings have ever been (at one point, someone quotes Father Mapple from Moby Dick — “for what is man that he should live out the life-time of his God?”), for the most part, the Leonora Christine’s people respond well; the extreme strain sometimes produces extreme effects, but no one commits suicide. (I suspect that Anderson knew that in such a situation, if just one person took that way out, it would likely be the effective end of everyone.)

Soon they have left, not only our own galaxy, but also the supercluster of galaxies that constitute our local “neighborhood”, in the hope of reaching a region in which radiation levels will be low enough to permit them to make their repairs. As these “empty” gulfs are completely uncharted, they are also trusting that chance (or that God whom some of them still believe that they have not outlived) will eventually bring them to a galactic group where they will find a suitable planet.

Unexpected difficulties continue to intervene, however, and by the time they are able to fix the damage and decelerate to begin their search for a new home, there is no longer any potential home to decelerate to; so much time has passed outside the ship that the expansion of the universe caused by the original Big Bang has reversed. The universe is now contracting in a “Big Crunch” in which all matter and energy are forced closer and closer together until the cosmic cycle will restart with another Big Bang.

What is there for the Leonora Christine to do but circle the cosmic seed and attempt to ride out the coming explosion and then try to find a young world to begin again on? That’s just what they are able to do, and the story that began on an old planet in an old galaxy in an old universe ends on a new planet in a new galaxy in a universe that didn’t even exist when the story began, uncounted trillions of years before.

The book closes with Charles Reymont and Ingrid Lindgren, two people who now constitute one twenty-fifth of the entire human race, standing on the soil of the home they have travelled such an inconceivable distance in time and space to reach. “Here was not New Earth”, Anderson says. “That would have been too much to expect.” But it is a place where the stubborn, resourceful, endlessly hopeful human race will be able to start anew, a place where it will have a chance to take root and flourish… and perhaps, avoid some of the mistakes that plagued it long ago in a universe that now no longer exists.

Charles Reymont, the man whose determination saved the entire human race, lightly rejects the suggestion of kingship that Ingrid Lindgren jokingly (but also not entirely unseriously) makes, and then “he laughed, and made her laugh with him, and they were merely human.”

Pardon my French (a language once spoken on the long-extinct planet earth), but… holy shit!

Tau Zero was called by James Blish the “ultimate hard science fiction novel.” It’s certainly difficult to think of one that could go beyond it; every time I finish reading it, I want take my brain out, shake it a little, massage it, and run it under a cold faucet before putting it back in my skull. It’s a book that takes your perspective and stretches it, and stretches it, and keeps on stretching it until you walk around bumping into walls because you’re so far from where you started that you have no idea where you are anymore and can’t even begin to imagine where you’re going to end up when you’re finished.

Even in the science fiction genre, there aren’t many books like that. Even a lemon-sucking, hard line anti-Campbellian anti-sentimentalist like Barry Malzberg grew positively misty whenever he talked about the book. Calling the novel “magnificent”, Malzberg rhapsodized that Tau Zero was “the only work published after 1955 that can elicit from me some of the same responses I had towards science fiction in my adolescence — a sense of timelessness, human eternity, and the order of the cosmos as reflected in the individual fate of every person who would try to measure himself against these qualities.”

This wasn’t just Malzberg indulging in nostalgia; Poul Anderson’s book, which marries a modest nuts-and-bolts style with a beyond-audacious premise, really does what Malzberg says it does, and in doing so it goes beyond the merely mind-boggling; it squares the boggle and keeps on squaring it until you’re so dizzy with infinitely expanding possibility that you have to lie flat on the floor for a while. For me, it’s the wildest, most exhilarating trip in all of science fiction.

I’m not going to return to the definitional task that I disavowed when I began this piece, but I do know that one of the things that we most want from a science fiction story is that when we finish it, we won’t end up back where we started. We want it to take us on a voyage, the kind of voyage that no other kind of writing can accomplish or even attempt.

If you want to know what kind of voyage that might be, I can do no better than to turn you over to one of the genre’s greatest voyagers, Poul Anderson, and commend to you his indeed magnificent novel, Tau Zero. When you’ve finished reading it, you might just feel — along with me — that what you’ve been holding in your hands is nothing less than the beating heart of science fiction.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was The Gorey Century

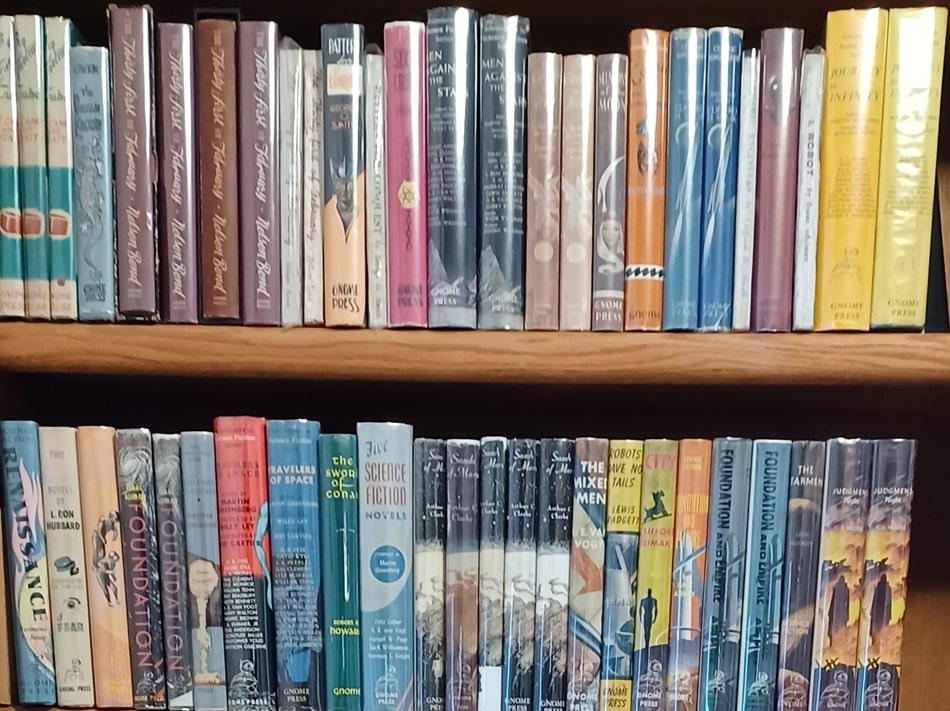

In the History of Vintage Science Fiction & Fantasy, Nothing Compares to Gnome Press

Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot and the Foundation Trilogy. Robert A. Heinlein’s Sixth Column. Arthur C. Clarke’s first three novels. The entire Conan saga from Robert E. Howard. The International Fantasy Award winner City by Clifford D. Simak. The Hugo Best Novel winner They’d Rather Be Right from Mack Clifton and Frank Riley. Books by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, A. E. van Vogt, C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner, Murray Leinster, Frederik Pohl, Jack Williamson, Andre Norton, and James Gunn.

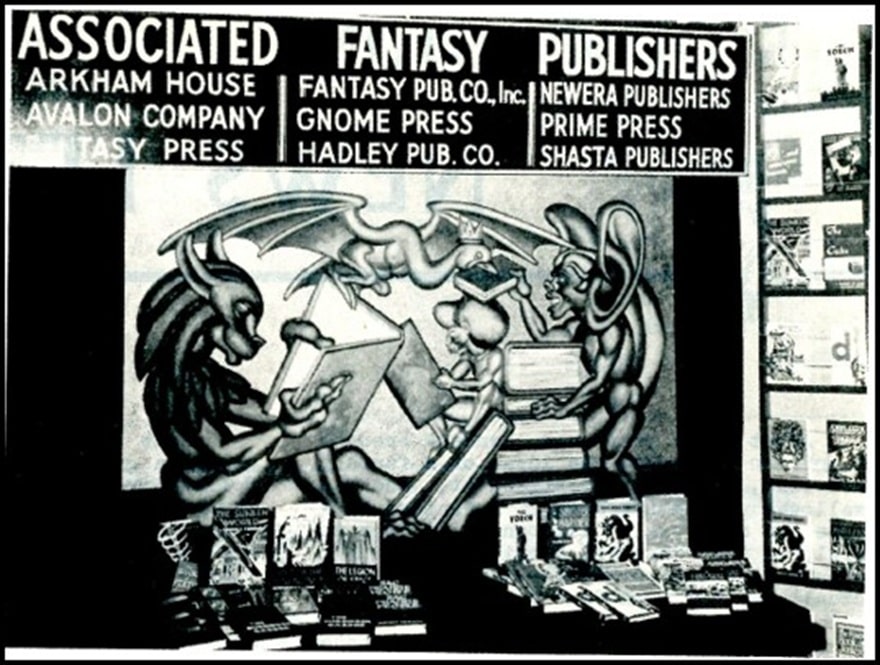

Those would be a solid core of any collection of vintage f&sf. Yet those books and dozens of others appeared in a few years from just one small publisher: Gnome Press.

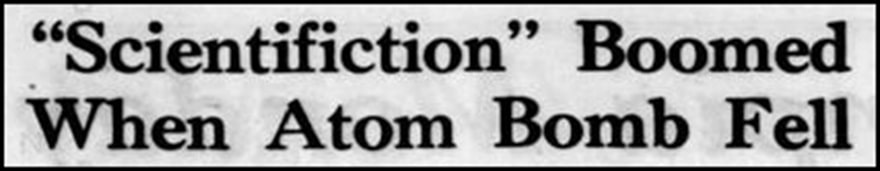

Fantasy had long been a staple of what we would now call mainstream publishing but before the 1940s American science fiction was relegated to gaudy pulp magazines, critically reviled as among the lowest forms of fiction. The superweapons that emerged from World War II, especially the atomic bomb, suddenly made the field look prescient, a look into the onrushing future.

Windsor [ON] Star, November 2, 1946With mainstream publishers still reluctant to mine magazine back issues, fans of the genre saw a publishing niche. More than a dozen small presses sprang into mayfly-like existence before 1950.

Windsor [ON] Star, November 2, 1946With mainstream publishers still reluctant to mine magazine back issues, fans of the genre saw a publishing niche. More than a dozen small presses sprang into mayfly-like existence before 1950.

Bloomington News Letter fanzine, February 1949

Bloomington News Letter fanzine, February 1949

Gnome was founded in 1948 by two members of New York fandom, Martin Greenberg and David A. Kyle.

The only known photo of Greenberg and Kyle together

The only known photo of Greenberg and Kyle together

Run on the proverbial shoestring, Gnome nevertheless outpublished, outsold, and outlasted all their competitors. Greenberg had a knack for making deals and Kyle did everything else, including drawing a half-dozen covers. He was soon obsoleted by young – and cheap – newcomers like Edd Cartier, Ed Emshwiller, and Frank Kelly Freas.

The firm made mistakes – could there be a worse response to the dawn of the Atomic Age than to drop three fantasies as its first three selections? – but quickly caught on to what the public wanted. Greenberg was a disciple of John W. Campbell who, whatever is thought of him today, then towered over the field as the guru editor of Astounding Science Fiction and Unknown Fantasy Fiction magazines. Whatever he touched, sold.

Greenberg used the magazines as his Comstock Lode and cannily offered to republish story series as “novels,” suiting post-war tastes if not the labeling laws. Authors flocked to Gnome’s door, desperately wanting hardback publication.

Well, that and money. Greenberg gave them only the former. He and Kyle split the proceeds fairly. Greenberg got a salary and Kyle didn’t. (Kyle always had multiple jobs and Greenberg had a family. But still.) Nevertheless, Kyle stayed six years and Gnome lasted fourteen, with Greenberg owing money to everyone in sight. He is usually described as a charming rogue with a gift of gab. Asimov once went to him demanding money and wound up lending more.

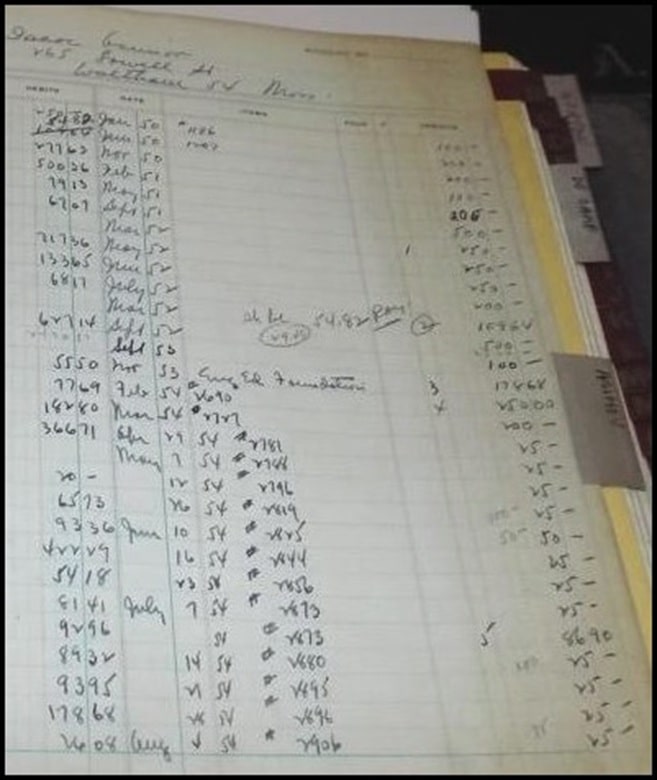

Isaac Asimov royalty payments, auction catalog

Isaac Asimov royalty payments, auction catalog

History is never pretty. Flaws and all, nothing compares to Gnome in the history of vintage f&sf. In many ways, it is the history of vintage f&sf.

I knew nothing about Gnome when I chanced upon several titles in a used bookstore in 1980. I had seen the name in passing, but histories of the small presses were nonexistent. I found a list of all 86 titles, and dove in. A few decades later I had them all. Did I stop there? What fun would that be? Gnome produced about 75 variants, with different boards or different jackets. Nobody knows exactly how many, because new ones keep popping up. Finding all of them is essentially impossible, which means the search never has to end – the perfect collectible.

Moreover, Gnome published a variety of ephemera, from newsletters to catalogs to calendars and I set out to accumulate all that appeared on the market. I even bought the 1951 Fantasy Calendar, which was an unparalleled achievement since it doesn’t exist. (Blame Donald Wollheim.)

Digging for information is infinitely easier today than in 1980, yet Gnome appears to have left virtually no paper trail, an oddity for a publisher dealing every day with paper. Other than a few scraps at Syracuse University, no business records seem to have survived and not even the indefatigable Kyle bothered to talk much about his time at Gnome in the millions of words he wrote for fanzines.

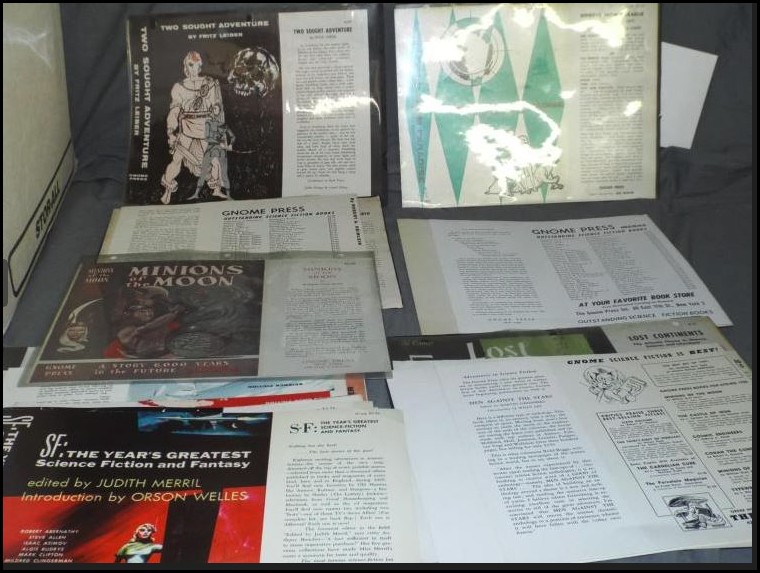

Gnome cover proofs, auction catalog

Gnome cover proofs, auction catalog

Nevertheless, dogged digging over decades created a repository of everything known about Gnome. Near archaeological level scrutiny of covers, flaps, copyright pages, and back panels yielded a history of each title. Each answered question led to ten additional mysteries. Eventually I wrote an utterly unpublishable 660-page manuscript dump that would require more than a thousand images to elucidate the text.

What’s 150,000 words and 1100 images to the internet? I already owned the URL GnomePress.com. The 113 pages there now comprise the first complete bibliography of Gnome Press (by author, title, and publication date), a separate page for each title with color scans of every variant board and cover I own along with contemporary reviews and previously unknown photos of the more obscure authors, information about a range of associational items, and histories both of Gnome and the f&sf field up to the time of its founding.

For all its literally exhausting coverage, the site remains a work in progress. Gnome collectors continue to provide information that require revision to opinions I previously thought firm. If anyone reading this has even the slightest scrap they want to share, please contact me. Or just ask questions about Gnome. Anything, except how much a book is worth.

By the way, Marty Greenberg’s file copy of I, Robot inscribed to him by Asimov is listed on the internet at $50,000. If you’re the buyer, please contact me. I want to know all about you.

Steve Carper is the author of hundreds of articles on fascinating, if obscure and forgotten, tidbits of history, as well as the seminal book Robots In American Popular Culture. All of his websites are linked at SteveCarper.com.

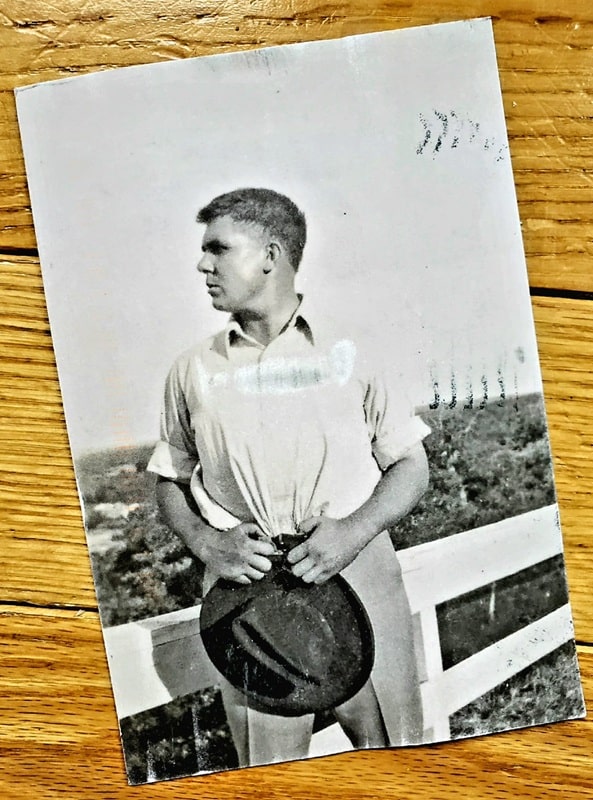

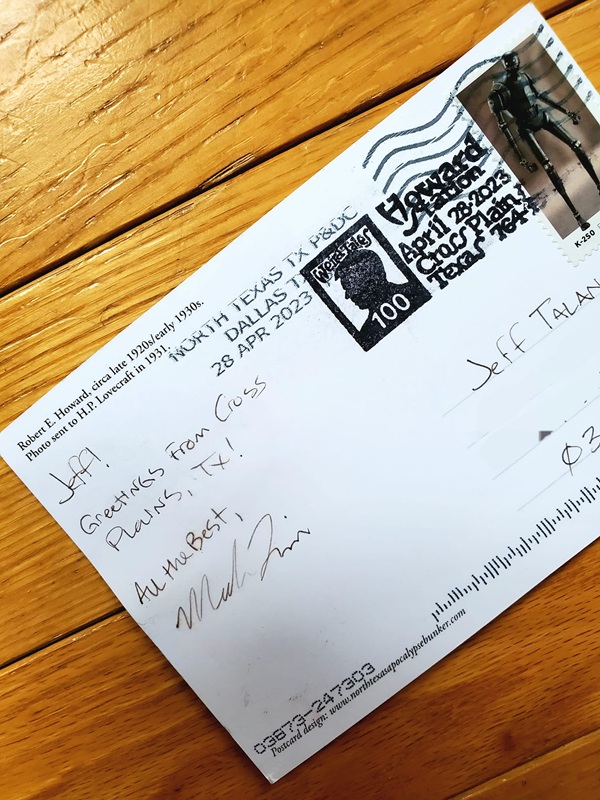

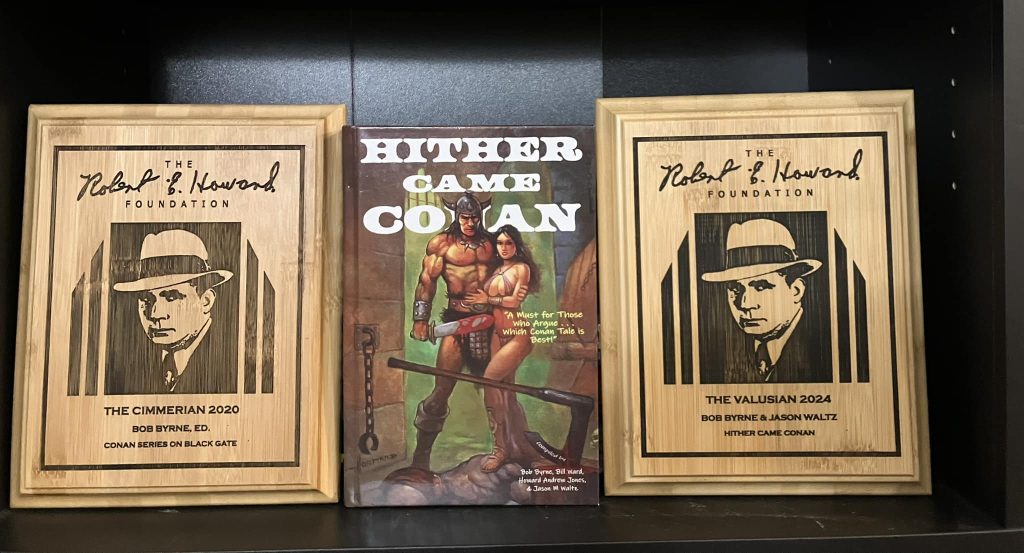

’24? in 42′ with…Bob Byrne????

Jason Waltz kicked off season two of his 24? in 42 podcast interviews with your very own Monday morning columnist. The prior installment was with Malazan’s Ian C. Esslemont, so I’m in pretty good company here.

It should not surprise you that I was all over the place, covering Robert E. Howard, Michael Moorcock, Columbo, books on writing and screenwriting, Encyclopedia Brown, the Civil War, Tolkien, The Constitutional Convention of 1787, Lawrence Block, Steven Hockensmith, Norbert Davis, and much more.

Jason sends sixteen questions ahead of time, and mixes in eight ‘new’ ones that can be definite curveballs. He started things off with a knuckleball! (Last week’s post was on baseball- I’m still in the mood)

Here are two sample questions:

Who is the visual artist(s) that creates the artwork that most moves you?Michael Whelan and Walter Velez (those terrific early Thieves World cover novels) are two of my favorite fantasy artists. Being a mystery guy, I LOVE some color paintings that Robert Fawcett did. Arthur Conan Doyle’s son Adrian (who waas a freeloading ass), co-wrote some Holmes stories. They’re not bad. All but the first appeared in Colliers’ illustrated by Fawcett. They are wonderful illustrations. Up there with the two great Holmes artists: Frederic Dorr Steele, and Sidney Paget. I find they capture Holmes.

How do you give depth to a character? Do you treat primary, secondary, and tertiary characters any differently?I consciously try to catch myself using a secondary or tertiary character as an info dump. Even a small one (and I absolutely do that). If the only reason I find them around is to give some info, I rework them. Or, try to use someone already in the story. There’s no depth to an info dump character.

The depth of a half dozen characters in the first Max Latin story (Watch Me Kill You) is about as well done as any story I’ve read. I try to give some personality, without making it a cliché.

Jason and I had a lot of fun, and you can actually see the enthusiasm that I bring to my blogging here at Black Gate. Settle in and watch (or at least listen) to me wax/ramble on. The 42 (from Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide) is the time target. Since I went over by about 35 minutes, I expanded on things a bit…

(42 is also Jackie Robinson’s number, and I talked about him for one question).

And for the record, since Jason called me out on camera: Ohio State defeated Texas in the CFP that night. In quite dramatic fashion, no less.

Click on over. I’m told I was a bit animated!

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

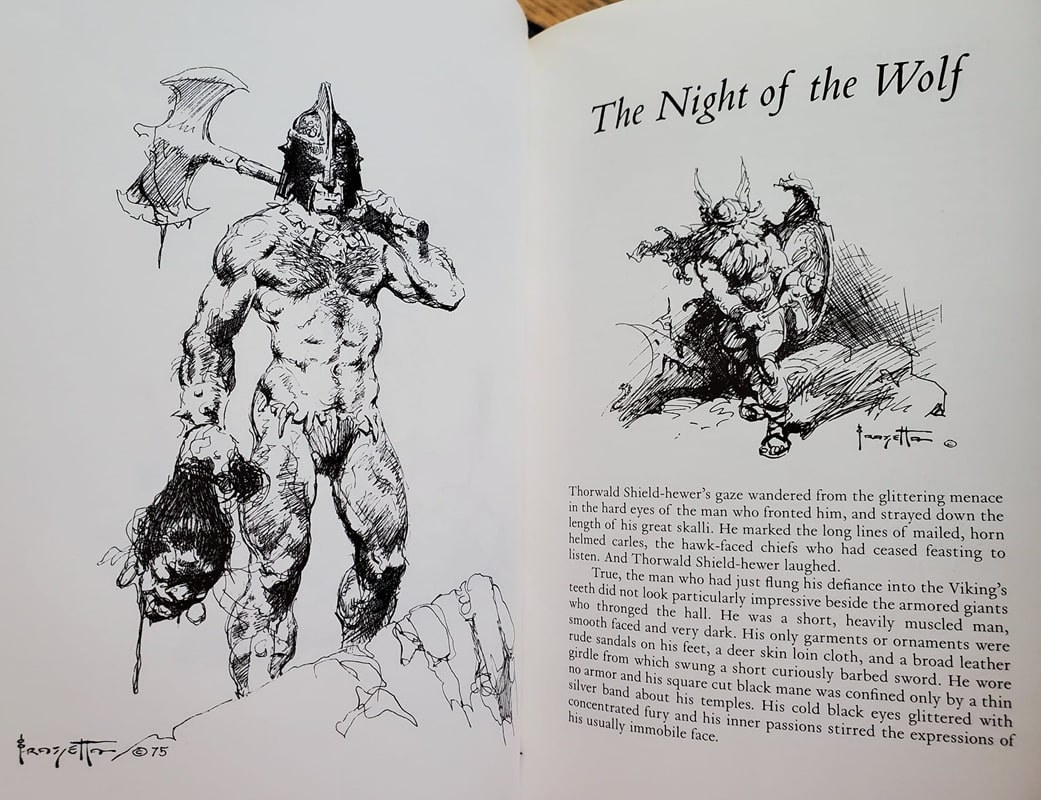

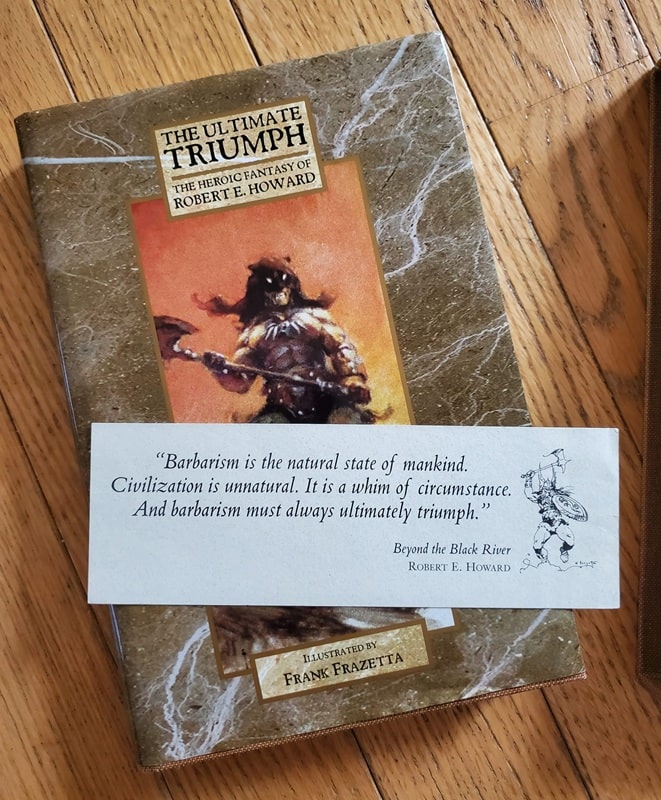

New Adventures for the World’s Favorite Barbarian

Conan the Barbarian: Battle of The Black Stone (Titan Comics collected edition, April 1, 2025). Cover by Jonas Scharf

Conan the Barbarian: Battle of The Black Stone (Titan Comics collected edition, April 1, 2025). Cover by Jonas Scharf

Few things are more ubiquitous than Conan and fantasy. Decades of sword-swinging high adventure has earned the barbarian a following most can only dream of. It’s taken the heavily thewed warrior to the big screen, Marvel Comics, and more. But it’s his latest adventure at Titan Comics that may prove to be the icing on the proverbial Shadizarian cake.

“This isn’t my first time writing Conan, but it’s definitely the most expansive opportunity I’ve ever had to chart the direction of such an amazing iconic character. I could not be happier in terms of our team and the collaboration we have in terms of story, art, and worldbuilding,” Jim Zub, writer of Conan the Barbarian at Titan Comics, shared by email.

[Click the images for Conan-sized versions.]

Over the years, few have come to understand the Cimmerian like the acclaimed Canadian scribe. Even in a career that has taken him to the heights of the comic book industry, Zub’s Conan work is special. His bibliography reads like a tour of the barbarian’s finest adventures of the past 10 years: Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian, The Savage Sword of Conan, and the epic Battle of the Black Stone are a few highlights. No wonder he’s so trusted by the rights holders of Robert E. Howard’s work.

“I actually work directly for Heroic Signatures, the rights holders of Conan and the Robert E. Howard character library. Titan publishes the comics in English, and they’ve been great publishing partners, but on a creative level I answer directly to the people who know Conan best and that has made the creative process really vibrant,” Zub stated.

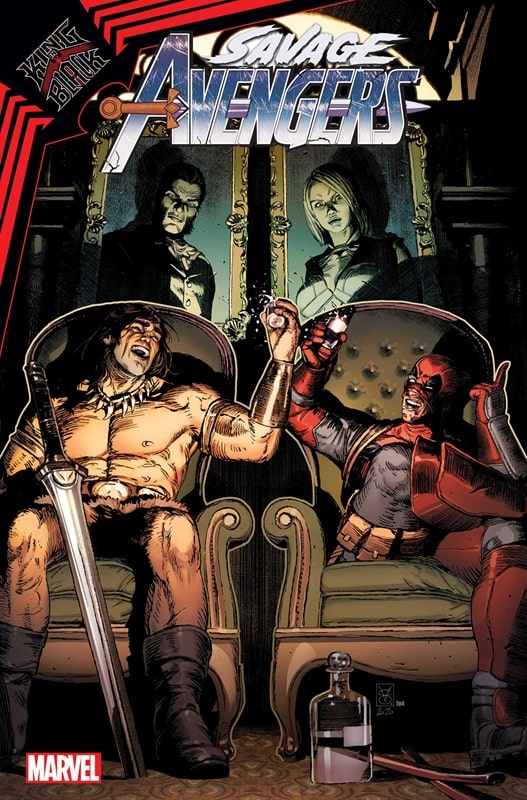

Conan and Deadpool in Savage Avengers #18, by Gerry Duggan and Kev Walker (Marvel Comics, February 17, 2021). Cover by Valerio Giangiordano

Conan and Deadpool in Savage Avengers #18, by Gerry Duggan and Kev Walker (Marvel Comics, February 17, 2021). Cover by Valerio Giangiordano

It wouldn’t be exactly fair to call Conan’s return to Titan a comeback. At Marvel, the Cimmerian had an impressive run in the much-loved Savage Avengers. Solo, he would be well-treated by Zub and his colleagues in stories like Conan: Serpent War and even fight symbiotes during the massive King in Black storyline. A look at the enthusiasm that has greeted Titan’s Conan series, however, tells you that this is something different.

Zub added, “Every time I get to contribute to characters and worlds I grew up with it’s a thrill, and this Conan publishing initiative is a whole new level.”

Such big breaks come with a heavy responsibility. After Howard created the character in the 1930s, many other writers would pen new tales for the Cimmerian. That lengthy list of scribes includes respected names like L. Sprague de Camp, Karl Edward Wagner, Roy Thomas, and Jason Aaron. How has he managed to stand out while writing a legacy character that has passed through so many legendary hands? Surprisingly, it’s by following the legends as closely as he can.

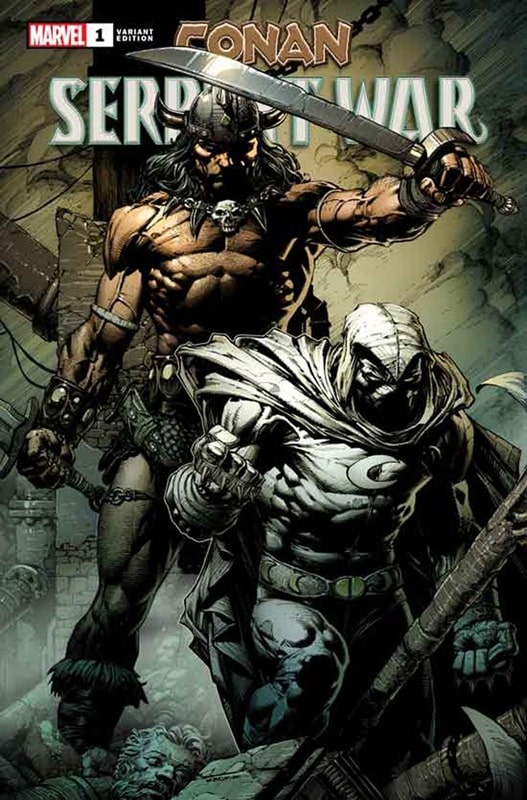

Conan: Serpent War #1, written by Jim Zub (Marvel Comics, December 4, 2019). Incentive variant cover E by David Finch

Conan: Serpent War #1, written by Jim Zub (Marvel Comics, December 4, 2019). Incentive variant cover E by David Finch

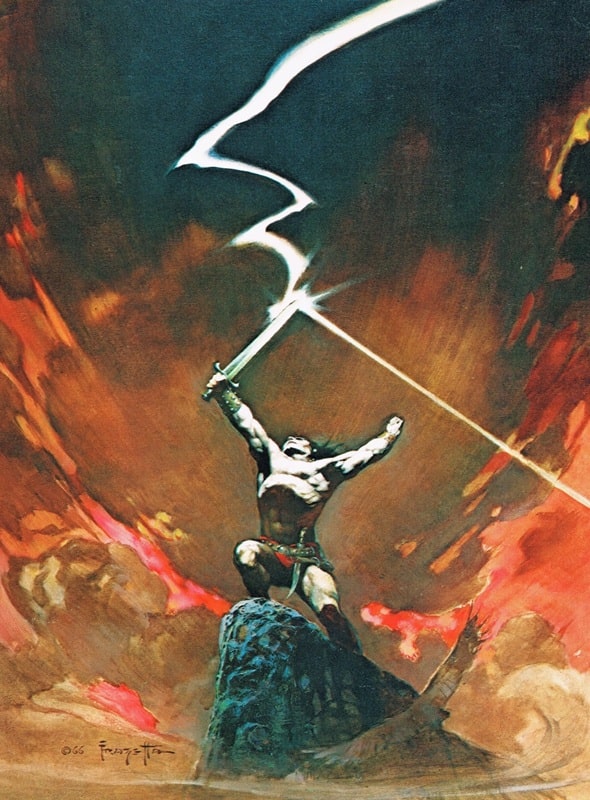

“If anything, I’m trying to hew as closely to Robert E. Howard’s original pulp characteristics as I can, while also incorporating the most iconic aspects of Roy Thomas’ seminal comic writing alongside the vision so many incredible artists like Frank Frazetta, Barry Windsor-Smith, John Buscema, Joe Jusko, Cary Nord and others have brought into it over the decades,” Zub explained.

Following in those footsteps brings with it plenty of challenges and opportunities. There aren’t many writers that understand that as well as Zub.

“The longer a character has been around, obviously, the more stories have been told and the harder it can be to surprise the existing fanbase while still staying true to who that character is. It’s a delicate balance where you want to keep core elements in mind but not close yourself off to new ideas,” Zub said. “The upside, of course, is the fact that legacy characters have that built-in recognition. I’m not building from scratch in terms of visibility and there’s an existing fanbase excited to see what comes next. The challenges and benefits are tightly wound together.”

You only need to read the massive Conan: Battle of the Black Stone limited series to see that approach in practice.

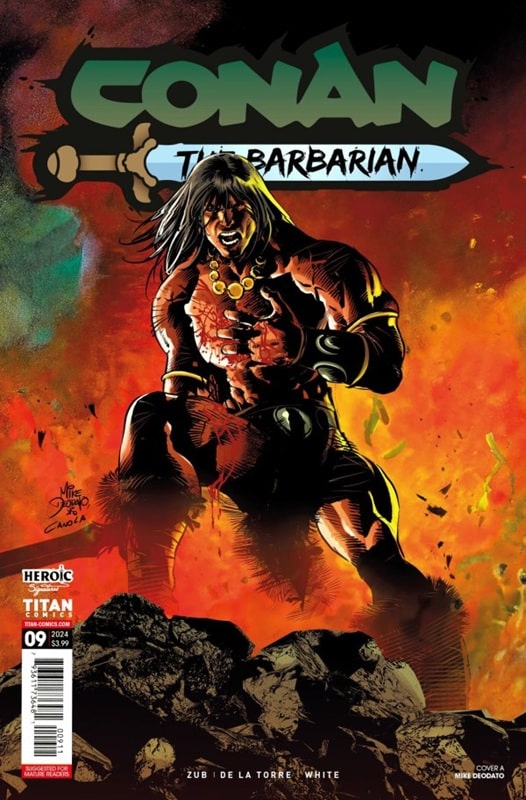

Conan the Barbarian #9, written by Jim Zub; art by Robert De La Torre and Dean White (Titan Comics, March 27, 2024)

A Walk With Titan

Conan the Barbarian #9, written by Jim Zub; art by Robert De La Torre and Dean White (Titan Comics, March 27, 2024)

A Walk With Titan

If one word could describe what it is like to read Titan Comics Conan the Barbarian, that word would be ‘fun.’ Not that it shortchanges readers on the artistic or deeper side of things. Far from it. The colors pop like a 70s comic, there’s no shortage of poetic allusions, well-crafted narrations, and action. But above all its bursting with creative energy, like a room of Conan’s most talented fans were allowed to cut loose.

“The new Titan series is a Mature Readers book, so we don’t have to hold back on violence or salacious elements where appropriate. That allows us to channel the intensity of the pulp source material even more closely,” is how Zub describes it.

Fans of high-fantasy and the barbarian’s sword-swinging antics will not be disappointed. Conan is at his most lethal in many of these stories, battling Picts and challenging sorcerers with his usual bravado. The ingredients of great sword and sorcery tales are all there: magic, romance, and plenty of mayhem.

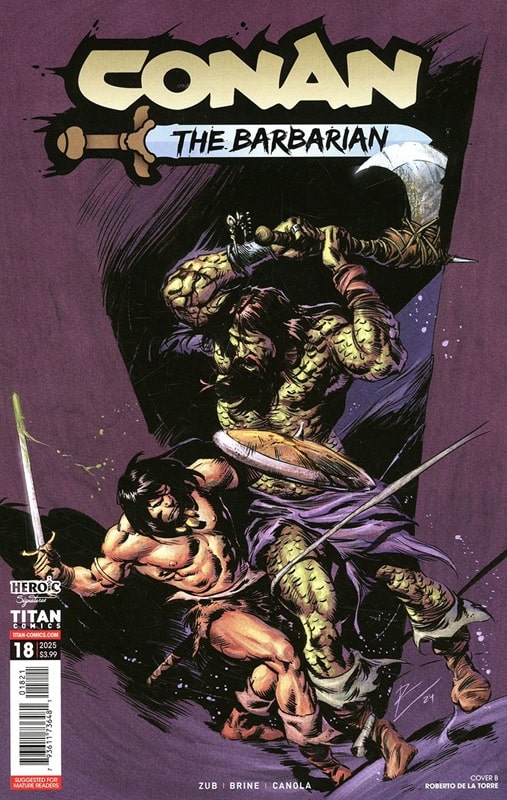

Conan the Barbarian #18, written by Jim Zub; art by Danica Brine and Joao Canola (Titan Comics, February 19, 2025). Cover B by De La Torre

Conan the Barbarian #18, written by Jim Zub; art by Danica Brine and Joao Canola (Titan Comics, February 19, 2025). Cover B by De La Torre

“It’s about distilling the best parts of past works and bringing them together with Howard’s own expansive mythmaking across the ages to tell epic stories of sword & sorcery. If I do my job well, it should feel “true” to old and new readers without falling back on adapting previous stories,” Zub said.

True to their epic vision, the creative team behind the series has not stopped at just celebrating the Hyborian Age. While the comics are full of respectful nods to the past, they also give Conan plenty of new obstacles to overcome. Other Howard characters are brought in and before you know it, a sprawling multi-timeline adventure is unfolding. Working on Conan, in general, has helped Zub level-up as a writer and his Titan Comics storylines feel like years of hard-work distilled for our reading pleasure.

“With each new storyline I’m pushing myself to use familiar pieces in unorthodox ways so that readers can see enough of the familiar to know that it’s still Conan, but knot know exactly which way the story is headed,” Zub said.

His evocative narrations have become integral to the experience. They set the tone, heighten the drama when necessary, and add some appreciated literary flair. It is no accident either that they read so quintessentially Conan.

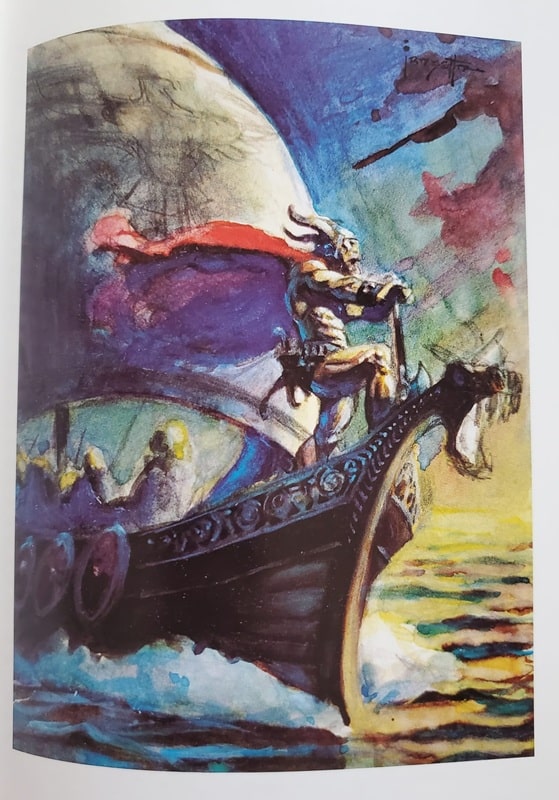

Classic barbarian art by Frank Frazetta: the cover to Thongor Against the Gods by Lin Carter (Paperback Library, November 1967)

Classic barbarian art by Frank Frazetta: the cover to Thongor Against the Gods by Lin Carter (Paperback Library, November 1967)

“I’ve marinated in the original Howard prose and analyzed it for cadence and vocabulary to make my narration feel like the classics without just copying it word-for-word. It’s made me think deeper about pacing, prose, characterization, geography, and culture,” Zub said.

The Battle for the Black Stone storyline has been a wild ride to say the least. While it’s impossible say where Conan is heading next, Zub’s work has left creatives of every level with plenty to learn from.

“There’s a reason why characters like Conan have stood the test of time and it’s crucial for people working on the property to understand and respect that bedrock foundation even while they bring their new ideas into the mix. Longtime fans can always tell if someone has done the research and cares about what they’re working on and, if you can win them over, it’s easier to build a strong audience from there,” Zub stated.

Ismail D. Soldan is an author, journalist, and poet. His work has previously appeared in Illustrated Worlds, LatineLit, and The Acentos Review among other publications. A proud explorer of both real and imagined worlds, his most recently published short story can be read in the January 2025 issue of Crimson Quill Quarterly, and his last article for Black Gate was An Eternal Champion’s Legacy.

Fan of the Cave Bear

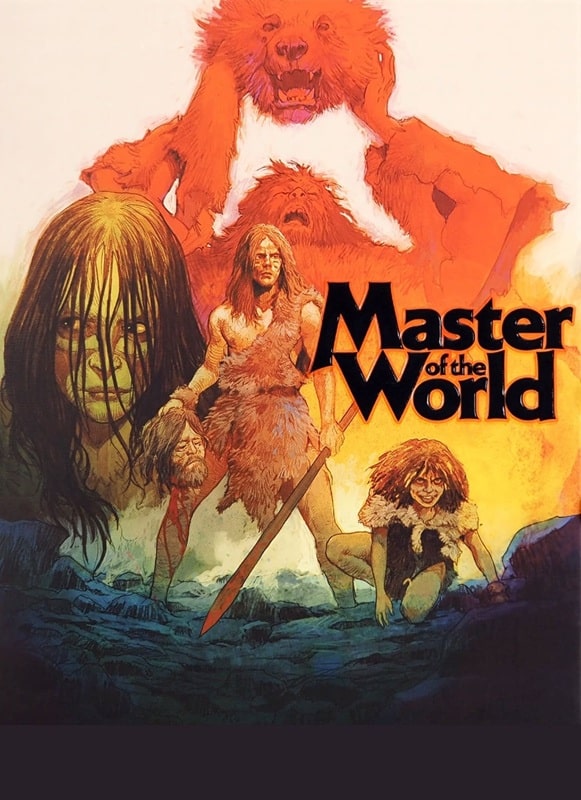

Master of the World (Falco Film, 1983)

Master of the World (Falco Film, 1983)

As usual, 20 films, all free to stream, and I’ve never seen them before. Can I really find 20 cave person films I can sit through?

EDIT: No. I’ve expanded the list to include any and all primitive cultures as there are not enough prehistoric flicks to watch.

EDIT: I’m capping this list at 10 – I can’t stomach any more f**king Italian cannibal flicks.

Master of the World (1983) TubiAgainst my better judgement, I’m starting a new list. The usual rules apply — 20 films, free to stream, based on a theme. This time, cave folk!

We kick off with this Italian offering from the early 80’s, obviously inspired by Quest for Fire and, um, possibly Caveman. It’s the old story of forbidden love, rival clans beating each other up and eating the brains of the vanquished, plus the invention of the bolas. It’s the Romeo and Juliet adaptation you never knew you needed.

The whole shebang is peppered with grainy stock footage of out-of-place animals and clouds, and there’s a man in a bear suit intercut with a real, heavily drugged bear, who beats the crap out of everyone. Actually, this semi-fake bear was a highlight.

As any nerd worth their salt will tell you, Ben Burtt used the sounds of a bear to create Chewbacca’s guttural growls. I swear to God, the filmmakers just took soundbites of Chewbacca from Star Wars and dubbed their own bear with them. Check it out — validate me!

Ultimately, a rather tedious affair, too much high-pitched grunting. I’m only one film in, and already regretting this.

3/10

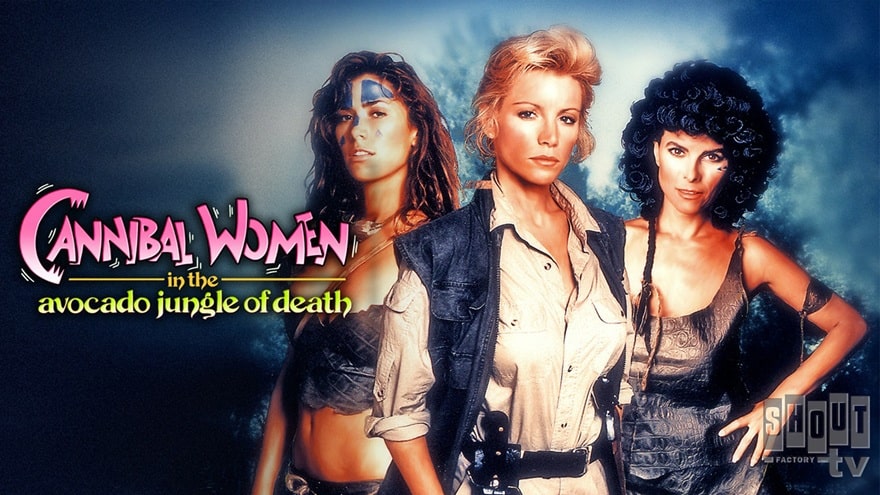

Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death (Paramount Home Video, 1989)

Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death (1989) Tubi

Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death (Paramount Home Video, 1989)

Cannibal Women in the Avocado Jungle of Death (1989) Tubi

Confession: I could only find about a half dozen prehistoric cave people flicks (that I hadn’t seen or are free to stream), so I have expanded the parameters to include any ‘primitive’ cultures or groups. This opens up the doors for a wider selection, and a lot more rubbish. Case in point…

I thought I had seen this, but I was probably confusing it with Amazon Women on the Moon — anyhoo, this is a weird little affair, very cheaply made, and a bit of a mess. I’ve seen it described as a comedy horror, but there’s no horror in it, and very little in the way of good comedy. The script, written by director J.F. Lawton (who wrote Pretty Woman and Under Siege!) is really not as funny as he thinks it is, flip-flopping between absurdist schtick in the Airplane vein, to satirical monologues — all of which outstay their welcome very quickly.

Shannon Tweed is perfectly fine as the lead, but Adrienne Barbeau is wasted, and the least said about Bill Maher the better (although he does nail a couple of pratfalls). The film claims to be a commentary on feminism and toxic masculinity, but neither theme is realised due the reliance on tired tropes (the male gaze, the white male savior). Oh well.

4/10

The Slime People (Donald J. Hansen Enterprises, 1963)

The Slime People (1963) Prime

The Slime People (Donald J. Hansen Enterprises, 1963)

The Slime People (1963) Prime

A primitive prehistoric race rises from the sewers to reclaim the planet after some misguided nuclear testing? Yes, this fits the criteria.

Is it any good though? Weeeellll…

It starts off pretty well. A lone pilot flies into a California airport, only to find the entire town deserted. It’s well set up, and would be even more effective if the film hadn’t shown us the titular monsters as soon as the film starts, before the credits. The monsters themselves are quite interesting, however it looks like they blew the budget on three full-size costumes; think Dr. Who‘s Zygons wearing gorilla pants.

The rest of the ensemble is made up of the usual suspects: lantern-jawed Clark Gable-lite, useless scientist, useless scientist’s useless daughters, useless marine (only there to say ‘gee whiz’ and kiss a useless daughter) and a nutcase who has ‘uncomfortable feelings’ for his goat. You read that right.

The whole affair is shrouded in fog (a major plot point) as mostly consists of lots of talking and running through the afore-mentioned fog. It’s a bit rubbish, but strangely compelling.

5/10

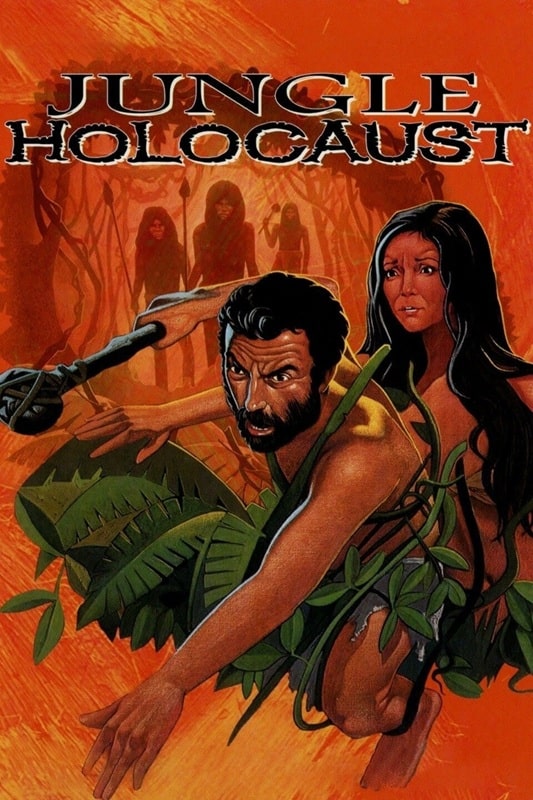

Jungle Holocaust (Erre Cinematografica, 1977)

Jungle Holocaust (1977) Tubi

Jungle Holocaust (Erre Cinematografica, 1977)

Jungle Holocaust (1977) Tubi

Of all the horror sub-genres, jungle cannibal ones are my least favourite. There’s simply no joy to be found in any of them, and combine them with the Italian predilection for animal cruelty, and you’ve got a film I never need to see twice. This one is the first foray into the genre by the much lauded Ruggero Deodato, and it’s not as ghastly as his later offerings, but still enough to leave me questioning my life choices. I can deal with the human-on-human buffets, but the suffering of real animals turns my stomach.

Anyhoo — it’s the usual plot; white Italians enter the jungle, get eaten. Along the way there is stock footage of animals eating each other, ants in wounds, copious willy tugging (some bad, some good) and lots of ‘oo, oo, oo’ ‘aah, aah, aah’.

The leads are pretty good, Massimo Foschi really sells the whole jungle madness look, and Me Me Lai is great as the loveliest cannibal of them all. However, at the end of the day I don’t mean to be judgemental, but I have no idea how anyone can watch these for a good time.

6/10

Atragon (Toho, December 22, 1963)

Atragon (1963) Prime

Atragon (Toho, December 22, 1963)

Atragon (1963) Prime

A tenuous fit for this project, Atragon features an ancient civilization (the Empire of Mu) hellbent on reclaiming their position as rulers of the world. For now, their continent lays at the bottom of the Pacific, so the film is all about Japan’s experimental submarine program, patriotism, and nefarious agents.

The entire world rallies via stock footage as the Mu Nemo themselves around the globe, sinking ships and being a general nuisance. Lots of lovely matte paintings and Thunderbirds-style models, and a bonus sea monster at the end. I had fun.

6/10

Teenage Caveman (American International Pictures, July 1, 1958)

Teenage Caveman (1958) Prime (AMC+)

Teenage Caveman (American International Pictures, July 1, 1958)

Teenage Caveman (1958) Prime (AMC+)

Yes, I started a free 30-day trial sub to AMC+ just so that I could watch this movie without the MST3K voice track. Such is my commitment to this pointless exercise in procrastination.

Anyhoo — here we have Roger Corman writing and banging out a caveman film in a couple of weeks. All shot on one California location, amply sprinkled with footage from other AIP flicks, featuring a very young Robert Vaughn as a young ‘cave person’ in the midst of an existential crisis. The clan he belongs to is the cleanest, whitest bunch of knuckle-draggers you’ve ever seen, and their hair is perfect. They all adhere to a bunch of rules attributed to Sky Gods and Monsters (TM), but Bobby Vaughn ain’t down with no rules, daddio.

He rebels, as all teens should, and while the elders sit around at camp discussing the rules, he goes out to see what’s so dangerous about the other side of the river. Here’s the thing, despite it being cheesy as hell, and somewhat laughable, Vaughn plays it straight (the right choice) and Corman clubs us around the head with a killer twist. I rather enjoyed it. Second film to feature a dude in a bear costume too, so it gains back the mark I was about to take away for the cruel real animal fighting.

6/10

Iceman (Echo Film/Lucky Bird Pictures, 2017)

Iceman (2017) Tubi

Iceman (Echo Film/Lucky Bird Pictures, 2017)

Iceman (2017) Tubi

Based on a 5300-yr-old mummy found by hikers in 1991, this German production proceeds to tell the imagined last days of a Neanderthal man, Kaleb. It’s a simple revenge flick, told in the ancient Rhaetic language, and is beautifully shot through with a suitably grim palette.

Jürgen Vogel as Kaleb is brilliant, bringing physical and emotional heft to every scene, and it was a treat to see Franco Nero pop up. It’s solid, at times horrific, and a reminder that revenge is a dish best served hunted, skinned and roasted.

8/10

Stone Age Sirens (Retromedia Entertainment, November 16, 2004)

Stone Age Sirens (2004) Tubi

Stone Age Sirens (Retromedia Entertainment, November 16, 2004)

Stone Age Sirens (2004) Tubi

Another Fred Olen Ray flick (credited as Nicholas Medina, his soft-core pseudonym), this one is a heavily edited version of the film Teenage Cave Girl, heavily edited to the point where there’s no actual Neanderthal nookie on display at all. By cutting out all the sex scenes, what you are left with is a rubbish comedy about a pair of cave dwellers who are transported to the future and fall in with some randy archeologists (there’s more than you knew).

Peppered with stop-mo shots stolen from Planet of the Dinosaurs and some abominable CG in all its 8-bit glory, this is the usual slice of fried shite I’ve come to expect from the once great Ray. It gets a point for only being 46 minutes long.

1/10

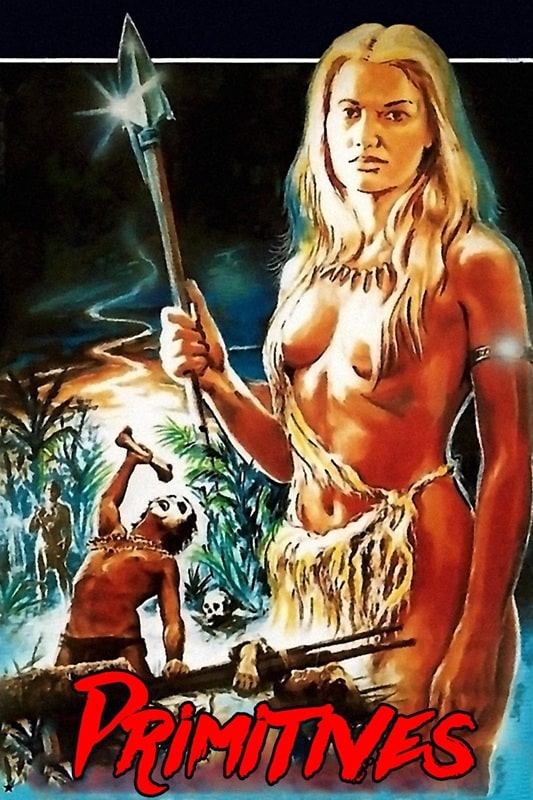

Primitives (Rapi Films, 1978) and Eaten Alive! (Dana Film, March 20, 1980)

This one is an Indonesian version of the Italian jungle exploitation flicks, and doesn’t just follow a similar plot, but lifts whole sequences directly for previous fare such as Cannibal Holocaust. In fact, it’s pretty shameless how much is ripped off from that movie, right down to locations and set pieces (although it stops short of actual tallywhacker removal). It’s full of the usual grunting and chomping, and the filmmakers seemed to double-down on the animal cruelty, using horrific footage from previous films.

It’s a miserable viewing experience, and I’m only giving it an extra mark for the shameless stealing of inappropriate music (Kraftwerk’s ‘The Robots, a trio of Jean Michel Jarre tracks and Princess Leia’s theme) and a hilarious rubber axe boomerang scene.

4/10

Eaten Alive! (1980) TubiNot to be confused with the Tobe Hooper ‘gator romp, this is another Italian cannibal flick that starts interestingly in New York, but then descends into the usual animal torture and misogyny associated with these films.

It’s held together by a flimsy ‘Jonestown’ plot, but this was the one that officially finished me off — I am totally done with this genre and never need to see another jungle cannibal film ever again. Hateful.

1/10

Previous Murkey Movie surveys from Neil Baker include:

There, Wolves

What a Croc

Prehistrionics

Jumping the Shark

Alien Overlords

Biggus Footus

I Like Big Bugs and I Cannot Lie

The Weird, Weird West

Warrior Women Watch-a-thon

Neil Baker’s last article for us was There, Wolves: Part III. Neil spends his days watching dodgy movies, most of them terrible, in the hope that you might be inspired to watch them too. He is often asked why he doesn’t watch ‘proper’ films, and he honestly doesn’t have a good answer. He is an author, illustrator, outdoor educator and owner of April Moon Books (AprilMoonBooks.com).

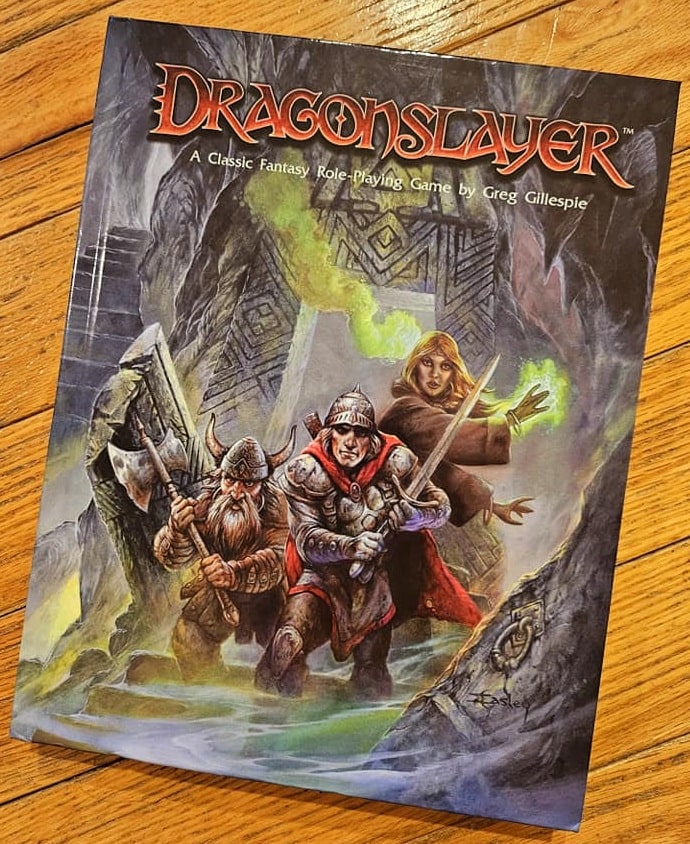

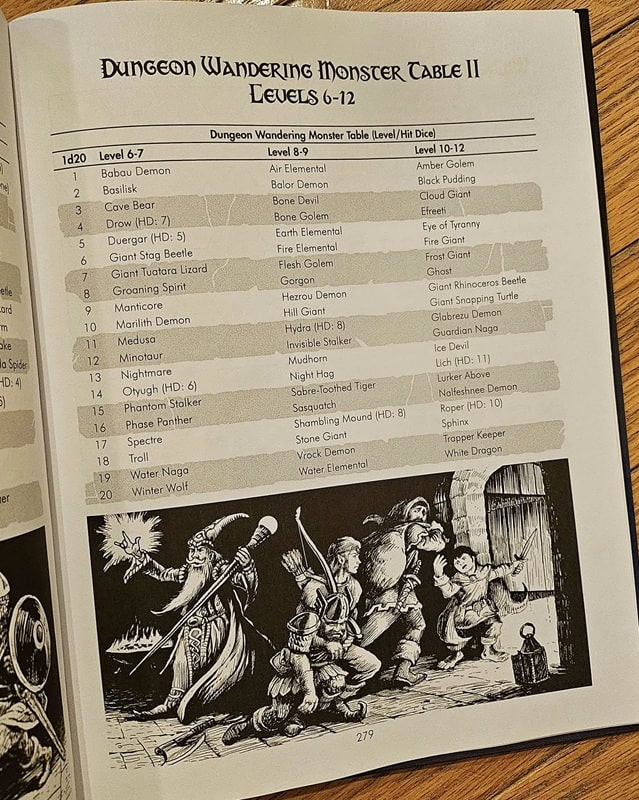

Rules for Mega-Dungeon Adventuring: Dragonslayer by Greg Gillespie

Dragonslayer (OSR Publishing, February 7, 2024). Cover by Jeff Easley

I’ve admired the mega-dungeon adventures of Greg Gillespie for several years, particularly Barrowmaze and The Forbidden Caverns of Archaia. Most recently, Greg published his own set of rules to go with those adventures. It’s called Dragonslayer, and I think it’s excellent. Here is the description from the back of the book:

Journey to a realm of myth and magic, where ancient legends and terrifying minsters come to life, and adventure awaits…

Inspired by the timeless role-playing tradition of the early 1980s, this ruleset seamlessly integrates the simplicity of B/X with the chrome if First Edition. The book has everything you need: classes, spells, monsters, and treasure, combined in a single volume.

For those who don’t know, “B/X” is the acronym for the Basic and Expert rules of Dungeons & Dragons.

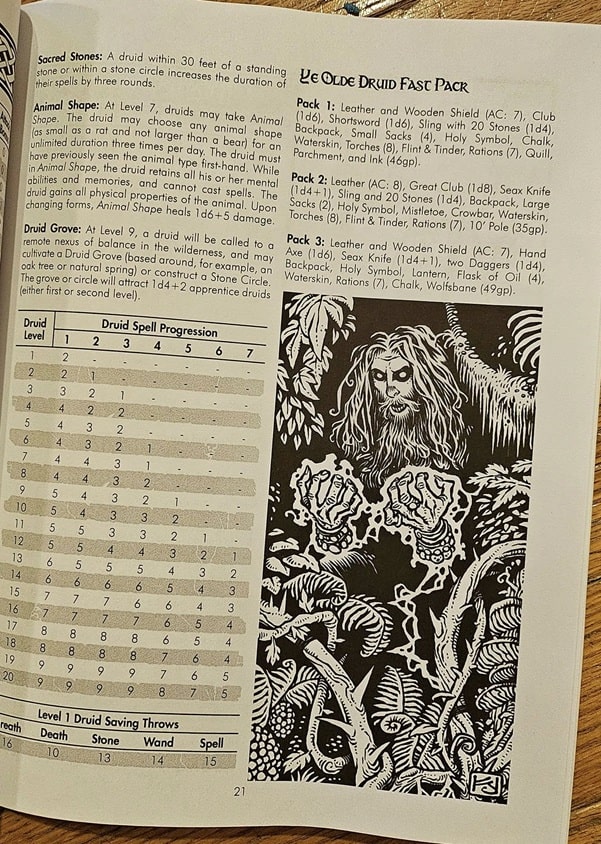

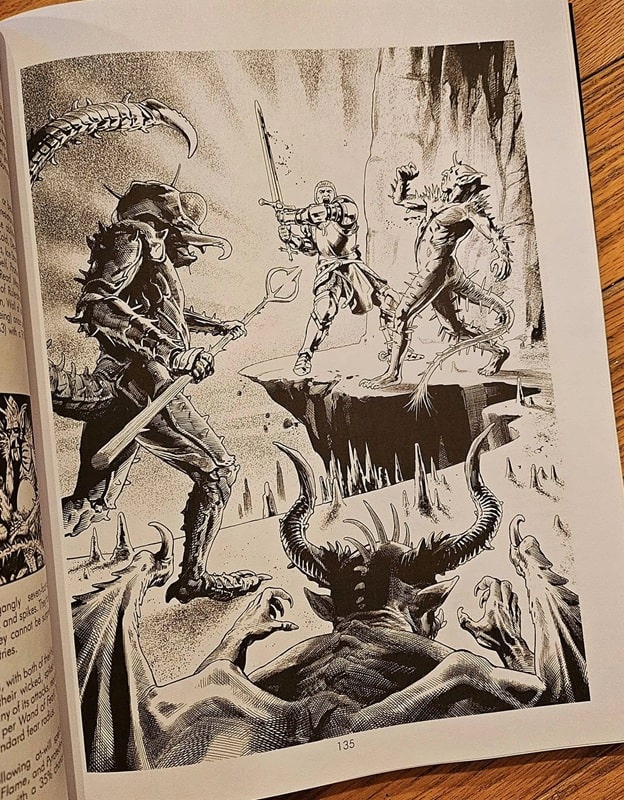

Interiors from Dragonslayer

The Basic and Expert rules were conceived by Tom Moldvay and Zeb Cook, who in turn derived their inspiration from the works of Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson — and also the previous Basic set (my personal favorite) compiled by John E. Holmes.

B/X is probably the most “cloned” version of D&D, yet Greg establishes his own flavor, quite admirably, within that framework. It’s nicely done!

Lastly, it’s really great to see art from the likes of Jeff Easley, Diesel LaForce, and Darlene Artist. All legends of the hobby whose work I have admired for decades.

Jeffrey P. Talanian’s last article for Black Gate was a review of Robert E. Howard’s “Worms of the Earth.” He is the creator and publisher of the Hyperborea sword-and-sorcery and weird science-fantasy RPG from North Wind Adventures. He was the co-author, with E. Gary Gygax, of the Castle Zagyg releases, including several Yggsburgh city supplements, Castle Zagyg: The East Mark Gazetteer, and Castle Zagyg: The Upper Works. Read Gabe Gybing’s interview with Jeffrey here, and follow his latest projects on Facebook and at www.hyperborea.tv.

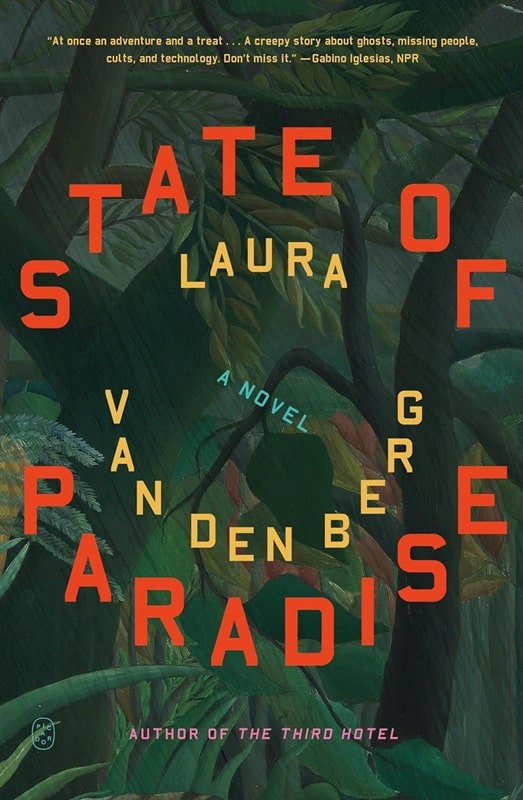

We No Longer Need Aliens to Feel Alienated: State of Paradise by Laura Van Den Berg

State of Paradise (Picador paperback reprint, July 8, 2025). Cover art:

detail from Tiger in a Tropical Storm by Henri Rousseau, 1891

When I was a kid there was a public service announcement on TV that went something like “Attention: Aliens. You are required by law to report by January 31st.” This was because of the Alien Act of 1940, otherwise known as the Smith Act. Basically, the legislation made it illegal to advocate the violent overthrow of the U.S. government and provided for a tracking system of non-citizens who, in the context of Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe and its then alliance with the Soviet Union, were potential suspects of espionage and sabotage. (Fun fact: prosecutions for advocating overthrow of the government have been ruled as unconstitutional violations of the First Amendment, in case you were wondering how any nitwit on social media can mouth off about doing just that.)

But as I didn’t know anything about this, the announcement always conjured an image of big headed, bug-eyed tentacled Martians registering at the local post office. Which I thought pretty funny. One thing I’ve learned over the years, and particularly these days, is that much of what adults say in all seriousness is often funny, but not in a “ha ha” way. More in a Jean Paul Sartre absurdist kind of way.

Needless to say, alien life forms are foundational science fiction, horror, and fantasy tropes. While some genre writers and filmmakers may very well have thought it just might be cool to tell stories about monsters from other worlds, the notion of aliens amongst us primarily serve as metaphors for, among other things, Communists and related usurpers of “normal” socio-political mores, fears of nuclear holocaust, technology run amok, repressed sexual desire, climate change, disease, and disembodiment.

Probably to a large extent due to the COVID-19 pandemic as well as severe climate events such as the California wildfires, today’s alienation storyline is less “aliens amongst us” and more “us alienated from the world.”

Which brings us to State of Paradise by Laura Van Den Berg.

The title is ironic, referring not only to Florida and its reputation as a refuge for the aged retired, the sunburned, and the weird, but that if the existential human condition is sometimes characterized using the Biblical metaphor of banishment from Eden, we currently find ourselves further away from Paradise than ever before.

In Florida, my husband runs. Ten miles a day seventy miles a week. a physical feat that is astonishing to me. He started running after he got stuck on a book he is trying to write, a historical account of pilgrims in medieval Europe. Back then it was not unusual for pilgrims to traverse hundreds of miles on foot… My husband is a trained historian and fascinated by journeys. He wants to understand what has become the pilgrimages in our broken modern world.

The first person narrator is

…a writer, though not a real one, I ghost for a very famous thriller writer. When I first got the job, I spent a month reading books by the famous author, to better understand the task that lay before me… the phrase everything is not as it seems appeared in nearly all the book descriptions.

Indeed, everything is not as it seems as the narrator (a kind of ghost herself) proceeds on a pilgrimage not only through actually weird Florida, where the 1930s Tarzan movies were filmed and non-native Pythons abound alongside Everglades alligators and Disney characters, but an alternate reality to which her sister and others somehow travel. Along the way are treated to torrential rain and flooding, sinkholes, virtual reality headsets, cults, and cats. And voluntary human extinction meetings. Just another day in Paradise.

With a history of being institutionalized, our narrator may be unreliable, and as a writer she is in the business of making things up. Not much cause for cognitive dissonance given the made-up unreliable narratives of our daily news cycle.

The plot, such that it is, concerns finding out what happened to her sister and others during their disappearances. And along the way what is happening to the narrator as she tries to figure out an increasingly strange world that nonetheless comes to define everyday existence. And whether she can trust what she is experiencing and what she remembers of those experiences.

Sometimes I wonder what we are supposed to do with our memories. Sometimes i wonder what our memories are for. A latch slips and the past floods in, knocking us flat. We leave places and we don’t leave places. Sometimes I imagine different versions of myself in all the different places I have ever lived, inching time in parallel.

This is a novel about the proverbial frog in boiling water, how because as the temperature only gradually rises, we don’t realize we’re being cooked. One absurdity follows another, and it is just how things are. We are now the aliens, journeying towards some unsettling destination, and we don’t have to bother to report.

One of the weirdest things about this period of time is the parts that still seem normal. Mundane and non-apocalyptical. Like how one minute we need an inflatable raft to cross the street and another we’re eating pasta at my sister’s house.

Or as Alice Cooper put it, “Welcome to my nightmare.”

David Soyka is one of the founding bloggers at Black Gate. He’s written over 200 articles for us since 2008. His most recent was a review of Polostan by Neal Stephenson.

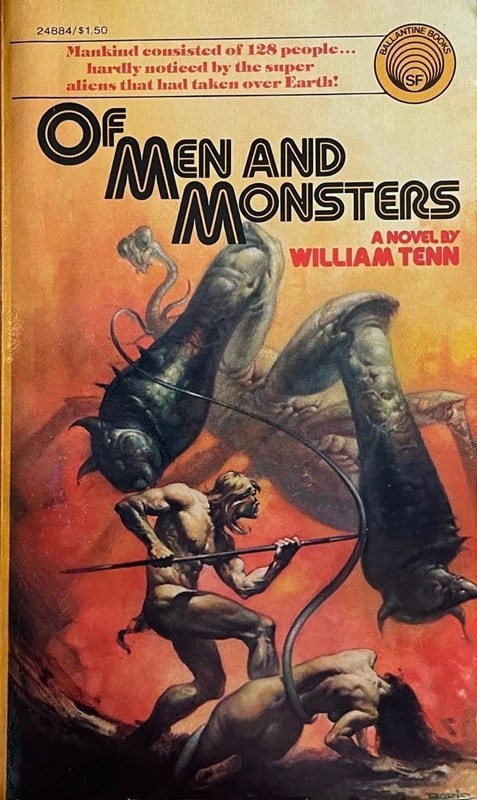

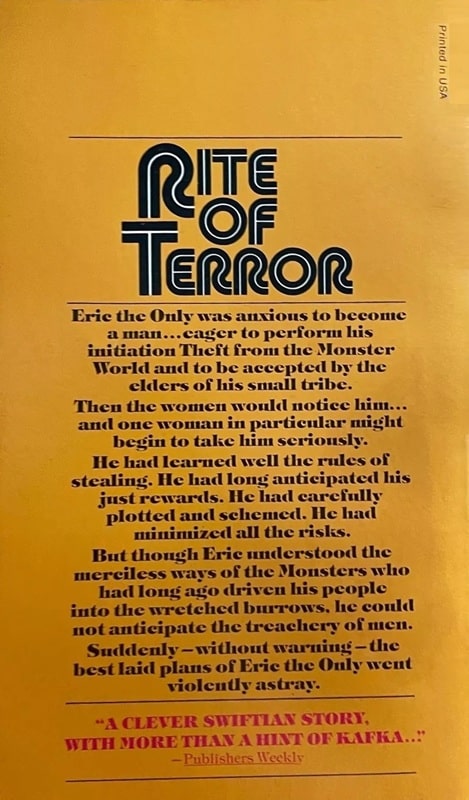

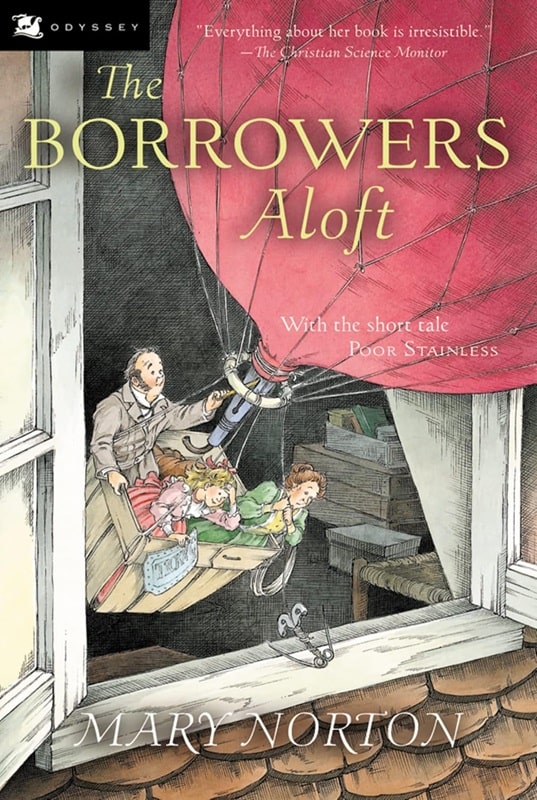

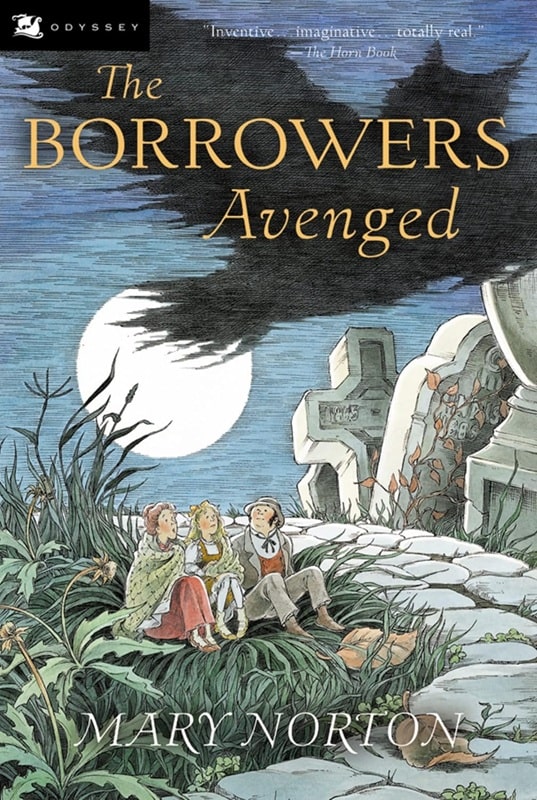

Of Men, Monsters, and Little People

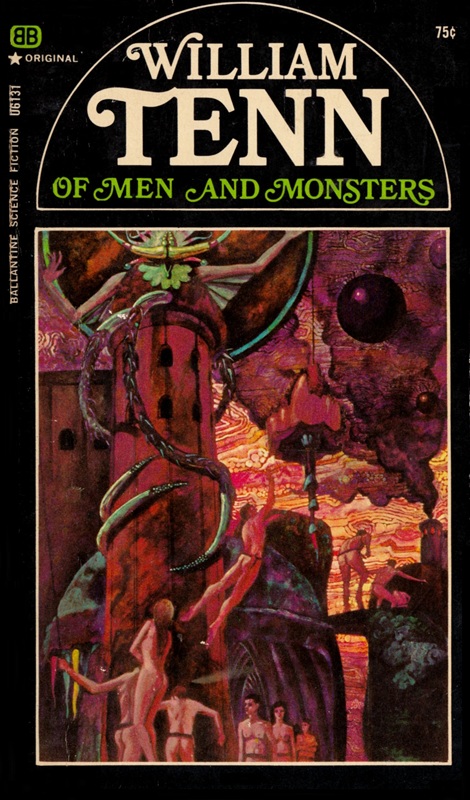

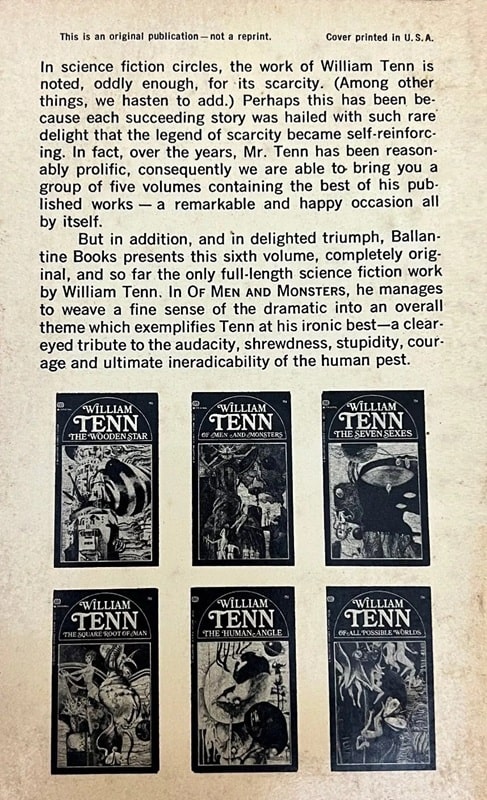

Of Men and Monsters, by William Tenn

(Ballantine Books, December 1975). Cover by Boris Vallejo

After posting about The Borrowers by British author Mary Norton (1903 -1992) last week, several people mentioned other books and movies with similar kinds of themes — little people living in the houses of big people. I thought I might take another post to discuss a few other examples from my own book collection.

First up is series by American author John Peterson (1924 – 2002). The first one was just called The Littles and was published in 1967, 15 years after The Borrowers (1952). The Littles live much like the “borrowers. They look human except for having tails. (In films they apparently look very mouselike but that’s not the case in the books.)

[Click the images for less little versions.]

The Littles, by John Peterson (Scholastic Books, 1991-1993 editions). Covers by Jacqueline Rogers.

The Littles, by John Peterson (Scholastic Books, 1991-1993 editions). Covers by Jacqueline Rogers.

Unlike with The Borrowers, I never heard of The Littles until I was buying books for my own son, (Josh), even though many were written when I was a kid. I stopped by Josh’s school to pick him up one day and they were having the Scholastic Book fair.

When I was a kid, we never had a fair where you could actually see the books, but we did get the order forms and I bought quite a few books through them for 25 cents or so when in grade school. I had to stop by this one at my son’s school and found out about The Littles. I bought every one they had, ostensibly for my son but at least halfway for myself. I read them all, too, although I don’t think Josh read them all.

There are a bunch of these books and more were written after Peterson’s death, but here are the ones I have. All covers are by Jacqueline Rogers, with charming interior illustrations by Roberta Carter Clark. (These are written specifically for children and I don’t think the stories are as good as in The Borrowers series, but they are fun.)

The Littles, 1967

The Littles have a Wedding, 1971

The Littles and the Trash Tinies, 1977

The Littles Go Exploring, 1978

The Littles and the Lost Children, 1991

The Littles and the Terrible Tiny Kid, 1993

In my twenties I came upon another series about tiny people. This was a trilogy by Gordon Williams (1934 – 2017) that included The Micronauts (1977), The Microcolony (1979), and Revolt of the Micronauts (1981) — all from Bantam Books.

The Micronauts by Gordon Williams (Bantam Books, August 1977, May 1979, and August 1981). Covers by Boris Vallejo, Lou Feck, and Peter Goodfellow

The Micronauts by Gordon Williams (Bantam Books, August 1977, May 1979, and August 1981). Covers by Boris Vallejo, Lou Feck, and Peter Goodfellow

These are SF novels, not to be confused with the toy series and comic book series from Marvel with the same name — which I’d never heard of until I started looking into stuff for this post. The difference here is normal sized people are cloned at 1/8th their natural size in order to deal with a catastrophic future where most natural resources have been exhausted. The experiment is set up in a controlled environment but things soon get out of control.

I liked all three very much and they had some cool covers. The Micronauts has a Boris Vallejo cover and interior illustrations. The Microcolony has a wonderful Lou Feck cover that I love. Revolt has a Peter Goodfellow cover.

Of Men and Monsters, by William Tenn

(Ballantine Books, June 1968). Cover by Stephen Miller

The last book I’ll review today is one of the first adult SF novels I ever read, Of Men and Monsters, by William Tenn (1920 – 2010). It’s still a fond memory. Tenn was the pseudonym for a British born author named Phillip Klass, although he moved to the US before he was 2. The book was published in 1968 and I read it in a library edition, but years later I bought a Del Rey printing with a great cover by Boris Vallejo (see top).

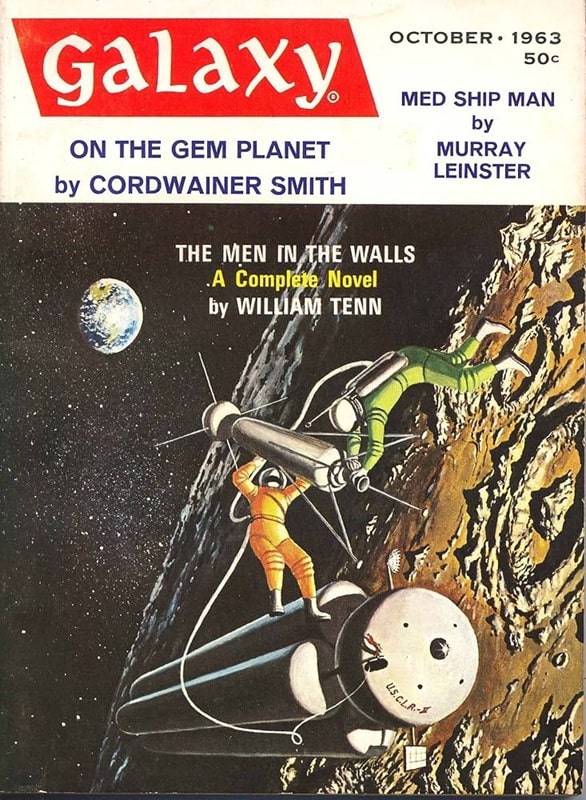

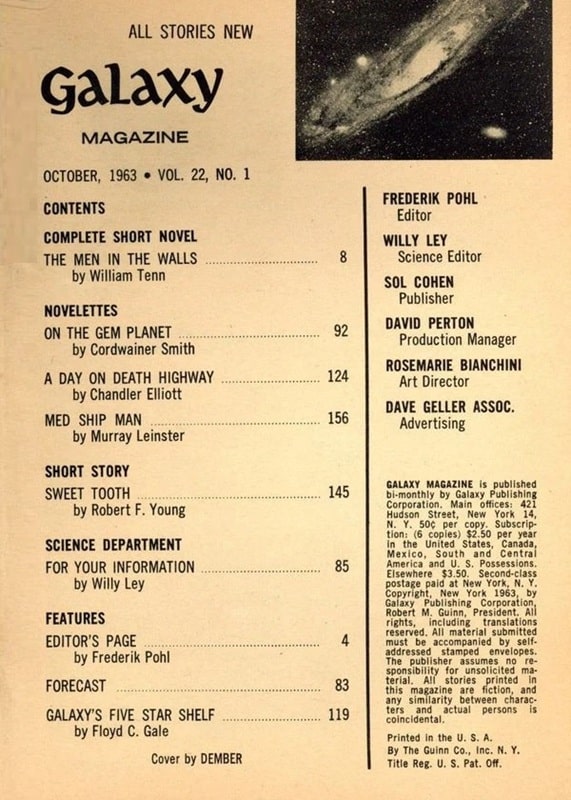

This one has its own twist on the theme. The people are normal sized, but they are survivors of an invasion by gigantic aliens so huge that the humans can live like mice in their walls. I just loved it, and found out from Adam Tuchman on Facebook that it was originally published in a shorter version in the October 1963 issue of Galaxy, called “The Men in the Walls.”

Galaxy, October 1963, containing “The Men in the Walls,” plus stories

by Cordwainer Smith, Murray Leinster, and more. Cover by McKenna

I’ll note that the ending Of Men and Monsters takes us into Sword & Planet territory.

There are plenty more I could talk about here, such as Lindsay Gutteridge’s Cold War in a Country Garden Trilogy, and Ben Sheppard reminded me of an awesome story called “Surface Tension” by James Blish, which deals with the miniaturization theme. There’s Asimov’s Fantastic Voyage, and even the movie Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, but this post is getting long as it is.

Charles Gramlich administers The Swords & Planet League group on Facebook, where this post first appeared. His last article for Black Gate was And Now For Something Completely Different: The Borrowers, by Mary Norton.

Taking the Ridiculous Seriously

Look! It’s fun! Image by Patrycja Kwiatkowska from Pixabay

Look! It’s fun! Image by Patrycja Kwiatkowska from Pixabay

Good afterevenmorn!

I hope everyone who has to suffer through the daylight savings shift Sunday are coping with losing that hour of sleep. To those to whom that does not apply, know that I am fiercely jealous of you. But let’s not dwell on our minor hardships. Today, I want to talk about writing, and very specifically how to make situations that are absolutely ridiculous on the outside feel real and very serious.

This came to me as I walked home from work today, thinking of my serialised novel (online on my blog every Friday until it concludes… look at me dropping a plug). It has, if you were to distill it down, the silliest, most ridiculous premise you could possibly imagine: Zombies, but make them hyper-aggressive, human-sized fairies.

Yup.

It’s so dumb. On the outside of it. And to be fair, I had so much fun writing it; giggling like a twit at how silly it all actually is. I take great delight in pointing out the hilariously ridiculousness of the premise. If I managed to do it well, then it will feel a good deal more serious than it seems when you distill it. If I pulled it off, it won’t feel how ridiculous it is. Whether I did or not is not really for me to decide, but here are some things I did in an effort to make it work. Maybe they’re something you can think about if you find yourself in a similar situation.

Image by Prawny from Pixabay

Image by Prawny from Pixabay

1. The situation might be ridiculous, but your characters don’t know that.

Let’s be honest. If you’re fighting for your life in a city that has been overtaken by a swarm of mindless winged humanoid killers, you’re probably going to be too busy trying to survive to worry about how silly it all actually is. That might come later, after you have done the surviving. If your characters treat their situation seriously (and it kinda is; they’re fighting for their lives), it’ll be much easier for your readers to suspend their disbelief while reading it. They’ll buy human-sized fairies attacking in swarms and consuming a city of millions in less than twenty-four hours.

It will probably also help to have at least one character who is familiar with really weird situations. Think of Mulder and Scully in the X-Files. They’re constantly facing things that, on the outside, are completely unbelievable, even ridiculous. But it works precisely because they take it seriously when they’re in the moment, and Mulder is a believer. However weird or out there a situation is, Mulder just accepts is as fact and rolls with it. It makes it easy for the viewer to do the same.

2. The situation is ridiculous, and your characters absolutely know it.

This isn’t an and/or situation with number one, trust me. If I found myself facing a mindless winged humanoid, I would absolutely demand of no one in particular what the actual f[redacted]. Having a character call out the idiocy of the situation they find themselves in — while taking it very seriously — is may be a way to get readers on board. This is especially true if the world you’ve built is encountering the situation for the first time.

If winged humanoids are a normal thing in the world, then having a character acknowledge how stupid that seems, will probably distance the reader and make it hard for them to suspend their own disbelief. However, if these creatures are not a part of your characters’ every day reality then having someone be absolutely incredulous at the situation they face will help your reader relate, making it easier for them to sink into the story.

It works for me, in any case. If the characters I’m reading aren’t absolute morons that question absolutely nothing, then I’m much more amenable to accept the scenarios they’re put through. Mind you, I’m not an especially critical reader, so I get sucked into stories a lot more frequently than most. It is both a blessing and a curse.

Image by Karen Nadine from Pixabay

Image by Karen Nadine from Pixabay

3. Keep it grounded

This might sound impossible, given the fantastic situation you’re trying to create, but keeping it as grounded as possible will help. There are a number of ways to do this. Providing real consequences for mistakes is one. Have people get hurt, or die. People will suffer in these situations if they ever actually happened; there will be grief, and fear, and anger. You’re already stretching incredulity with the situation. Have everyone dancing along unscathed will be pushing it much too far. This is especially important if it’s not taking place in a world that is easily relatable. I got a leg up, because the serial is set in a fictional city, but in the real world and set in 2024. There are a lot of touchstones that are easily digested for a reader.

It becomes harder if the entire world is fantastical. Finding something grounding in a world where trees talk or teleport, or whatever, is much harder. It’s not impossible, though. Find those touchstones and use them.

Did I achieve creating a story that brings people along and has them absolutely invested while also having gate silliest premise I think I could possibly conjure? No idea. But I tried, and I used these three (and other) things in the attempt. Maybe they’ll help you, too. If you’ve read books or are currently writing one which has an absolutely ridiculous premise, let me know what, and what worked (or didn’t). If you have any tips of your own for making a silly premise both believable and feel serious, also let me know in the comments below.

When S.M. Carrière isn’t brutally killing your favorite characters, she spends her time teaching martial arts, live streaming video games, and cuddling her cat. In other words, she spends her time teaching others to kill, streaming her digital kills, and a cuddling furry murderer. Her most recent titles include Daughters of Britain, Skylark and Human. Her serial The New Haven Incident is free and goes up every Friday on her blog.

Eleven Years of Monday Mornings with Bob

Wow. Eleven years ago today, on March 10, 2014, I became an official Black Gate blogger. The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes kicked off a three year run, bringing a mystery presence every Monday morning. I roamed off topic a bit – but NOTHING like I do now. I mean, did you read last week’s baseball post?

Encouraged by my buddy William Patrick Maynard (an established Black Gater), I went from some uknown guy commenting on other people’s posts, to a moderately interesting weekly columnist. And every World Fantasy Award-winning website, with an amazing roster of bloggers, needs a mystery column, right???

I talked about joining Black Gate in my chronicle of what passes for my writing career: Ya Gotta Ask.

And So It Began

By my count, I have written 510 posts here at Black Gate. That doesn’t include those posts I’ve hoodwinked folks…I mean, ones written by my gracious and talented friends. Discovering Robert E. Howard, Hither Came Conan, Talking Tolkien, and A (Black) Gat in the Hand have included some FANTASTIC stuff from others, and I’m very grateful to everyone who has used my Monday morning slot to make Black Gate even better.

I average about 1,000 words a post, and I frequently go over; I don’t go much under that (I write like I talk…). So, It’s not unreasonable to say I’ve written a half a million words here at Black Gate, over the past eleven years.

It’s been a fantastic ride, and I’ve gotten to write extensively about Sherlock Holmes, Robert E. Howard, Nero Wolfe, John D. MacDonald, Douglas Adams, Humphrey Bogart, RPGs and gaming, TV shows and movies, hardboiled Pulp, and pretty much anything else I like. I’m very ‘Squirrel!’.

I’ve created some regular features, such as What I’ve Been Watching, What I’ve Been Reading, and What I’ve Been Listening To (audiobooks).

Hither Come Came Conan will always be one of the proudest achievements of my writing career. And I honestly think if I could find out how, A (Black) Gat in the Hand should win some kind of mystery award.

I’ve tried to add new multi-contributor series’. I haven’t managed to pull one off for Solomon Kane, or John D. MacDonald, or Columbo, or Star Trek. But I haven’t necessarily given up yet. And I’m sure more will come to mind.

I have grown as a writer in many ways, in my eleven years at Black Gate. I know I’m a better blogger than when I started. Not that that would have been hard to do…

I did a 24? in 42 podcast interview with Rogue Blades’ Jason Waltz, which just dropped last week. It’s the topic of next week’s post.

When he threw me a curveball with the first question (‘What color do you write in?’), I ended up talking about engagement. I write about things I’m interested in. I rarely write negative columns. I don’t wanna spend a thousand words bitching about something I don’t like (I’ve got Facebook and Reddit for that). I will be critical, sure. But if I hate the latest ‘whatever it is,’ I’m gonna find something else to write about.

I wanna share things I’m interested in. I know some folks have gone on to check out topics I’ve talked about. My annual summer Pulp series has been good for that. And I like when people comment. It means I made some kind of connection. I try to reply to every comment, and I think I’m about 98%. Engagement.

I hope when somebody reads my Monday morning post, they enjoyed it. But more, I hope it resonated somehow. I’ve learned things, and gotten recommendations, from the comments. Engagement.

BG head honcho John O’Neil praised my stuff by saying I try to educate people. That’s part of me sharing stuff I enjoy. If there was a Norbert Davis Appreciation Society, I would be the president. So, I’ve written about the under-appreciated Black Mask Boy, several times. I’ve written a lot about Nero Wolfe, John D. MacDonald, and Terry Pratchett. They are three of my favorite writers, and I want to share with readers here. It’s obvious I’m a huge Douglas Adams fan, if you do a search on the site.

And I’ve certainly espoused my love of Robert E. Howard here at Black Gate.

I joke that I’ll keep doing a weekly column for as long as I can get around the firewall.

My life has changed a lot since I started this column. Divorce, moved, changed jobs (there was some kind of Pandemic, I hear…). But I have averaged 46 essays a year, for 11 years. And it would be many more, if I didn’t conned folks into writing some for me, once in awhile.

I talk about other Black Gaters who are Writers with a capital ‘W.’ And I consider myself a lower case ‘w’ writer.

But you know what? I’ve won three awards for my writing (and editing). You can buy my short stories in anthologies on Amazon. I was a regular columnist for a British mystery magazine. And I’m writing intros to books published by Steeger Books – sometimes with a cover mention. I followed Ian Esslemont (I’m a Malazan fan) on a podcast for authors. Ian Esslemont!

And I’ve been doing a thousand words a week, for eleven years. In this age, being a blogger is a valid way to write. I’m finally gonna give myself that capital W.

So, until they tighten up the firewall, I plan on continuing here at Black Gate for a while. Hope you keep finding things you like to read. And leave some comments. Let’s have a discussion.

Let’s engage.

And today’s post title is a nod to a popular memoir by sportswriter Mitch Albom, Tuesdays with Morrie.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

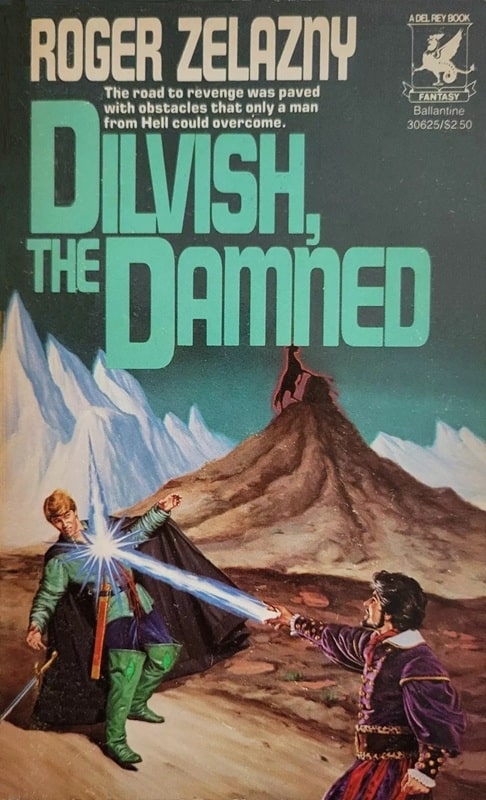

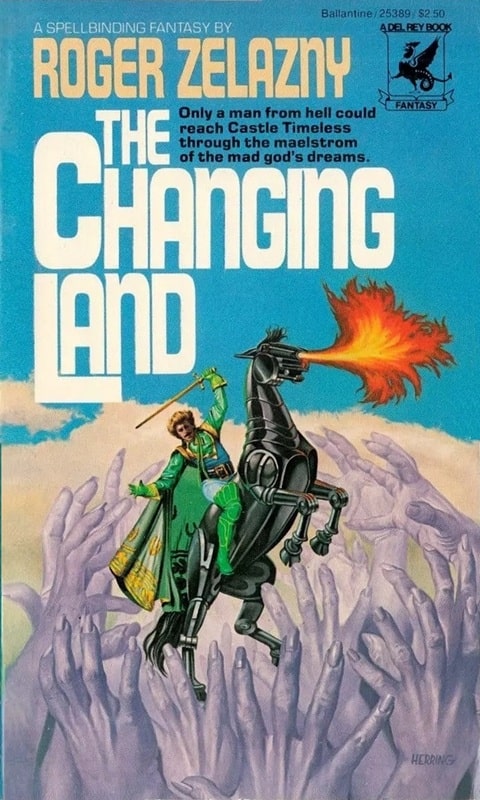

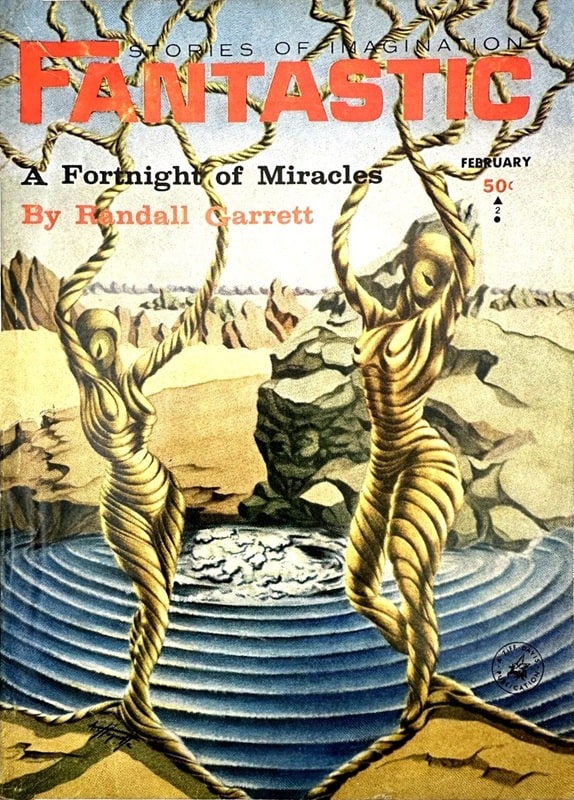

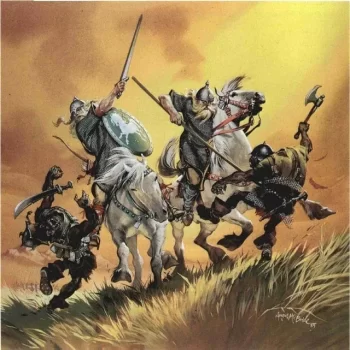

One of the Finest Achievements of Heroic Fantasy in the 20th Century: Dilvish, the Damned by Roger Zelazny

Dilvish, the Damned (Del Rey, November 1982). Cover by Michael Herring

Roger Zelazny was unquestionably one of the great American fantasists of the 20th century. That’s not to say he was perfect. His woman characters were often 2-dimensional, and he paired an unwillingness to work with an outline (“Trust your demon” was his motto) with a fondness for projects that really needed an outline.

But perfection is boring. Zelazny rarely is. Much of Zelazny’s work is on my always-reread list, anyway. He had a nifty way of putting things, and in describing the Amber series he brilliantly expressed the kind of fiction I love best and have often tried to write: “philosophic romance, shot through with elements of horror and morbidity.” Philoromhorrmorbpunk. That’s my genre. Or you could just say sword-and-sorcery.

Some people doubt whether Zelazny counts as a sword-and-sorcery writer, but he didn’t doubt it. He described not only the Corwin novels but also big chunks of Lord of Light as sword-and-sorcery. Some people think that a story only counts as S&S if it has a Clonan at its center, but as far as I’m concerned, if you’ve got an outsider hero on a personal mission in a landscape of magical adventure, and there are swords or other edged weapons, you’ve got sword-and-sorcery.

It doesn’t matter if it’s set in the deep future (e.g. Vance’s stories of the Dying Earth), or in an imaginary past (e.g. REH’s pioneering stories about Solomon Kane, Kull, Conan etc, but also C.L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry and Cabell’s tales of Poictesme), or another world (e.g. Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series).

And, anyway, Zelazny obviously counts as a sword-and-sorcery writer because of the Dilvish series. In some ways, it’s one of the finest achievements of heroic fantasy in the 20th century. In some ways, not. Details (a lot of them) ahead.

“Dilvish and Black,” fan art by Olga Sluchanko. Dilvish never had a cover painting this good in his damned life.

“Dilvish and Black,” fan art by Olga Sluchanko. Dilvish never had a cover painting this good in his damned life.

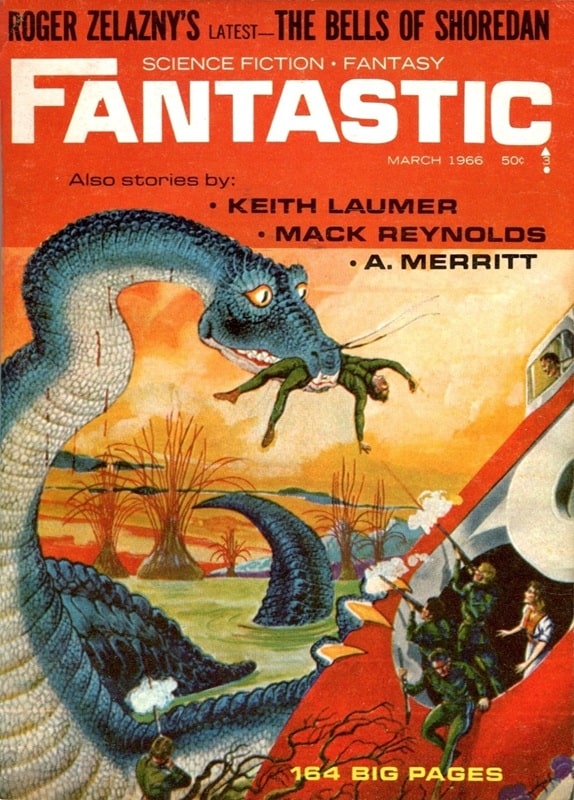

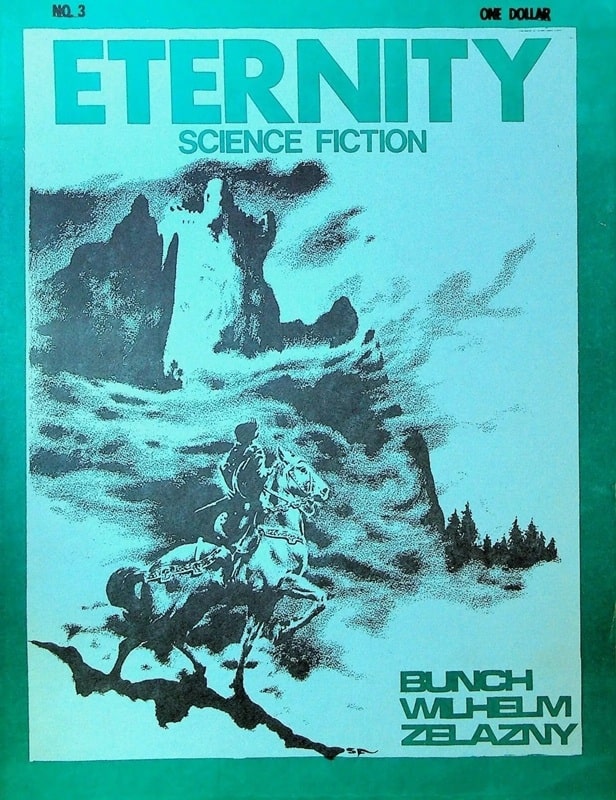

Dilvish, a.k.a. Dilvish the Damned, a.k.a. the Colonel of the East, first appeared in Fantastic under the guiding light of Cele Goldsmith, one of the great sf/f editors. After Goldsmith left the helm of Fantastic and Amazing, Zelazny continued to appear in those magazines, until he fell out with their new owner, Sol Cohen.

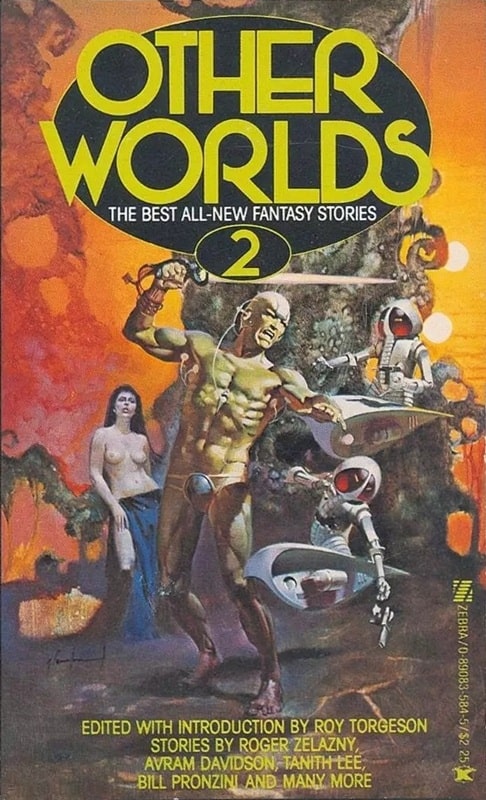

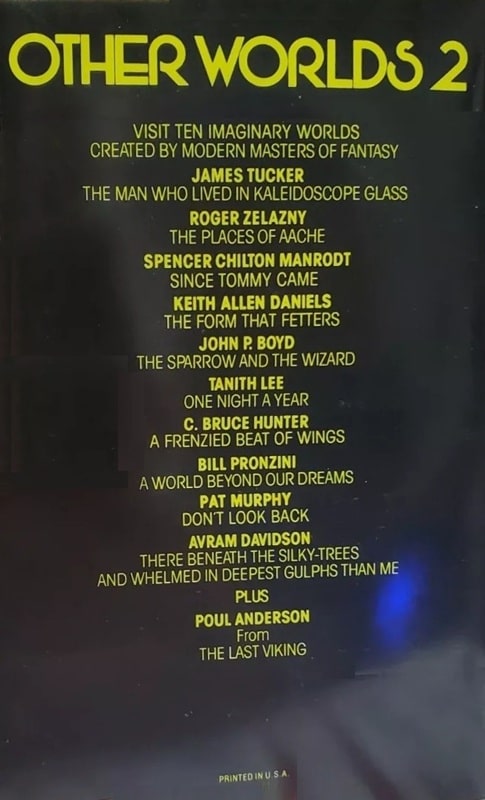

From that point Dilvish went into exile, the condition most natural for s&s heroes. He made appearances in a fanzine here, a small-press publication there. Zelazny’s hazy plan was to bring out a volume of Dilvish stories “to culminate in a possible novel, Nine Black Doves.” (Letter from Zelazny, 1965, quoted in the afterword to “Thelinde’s Song” in Power & Light.) When the Dilvish collection ultimately appeared from Del Rey in 1982, it was called Dilvish the Damned and it was paired with a booklength Dilvish adventure, The Changing Land.

A real golden age for Dilvish fans (which I had been since reading “The Bells of Shoredan” in a back-issue of Fantastic sometime in the mid-70s).

Or: maybe not.

The Changing Land (Del Rey, April 1981). Cover by Michael Herring

I didn’t glom onto these books as soon as they were published; I’d been drifting away from buying books as my life became nomadic (and chaotic) in my early 20s. When I did finally get hold of the volumes I was, to say the least, underwhelmed. I wasn’t crazy about the covers, for one thing. Michael Herring is a talented artist, but I like his work better for sf; these covers are kind of Brothers-Hildebrandtish. (From some, that would be praise, but not from me. De gustibus non disputandum.)

I also didn’t like the titles: Nine Black Doves is weird and evocative; Dilvish the Damned and The Changing Land are blunt and dull declarations, like a can of peas with a generic black-and-white label PEAS.

But a book by Zelazny is a book by Zelazny, so I bought both paperbacks when I had a chance… and was not crazy about them.

“Even Homer nods,” I said to myself, and put them in a box somewhere.

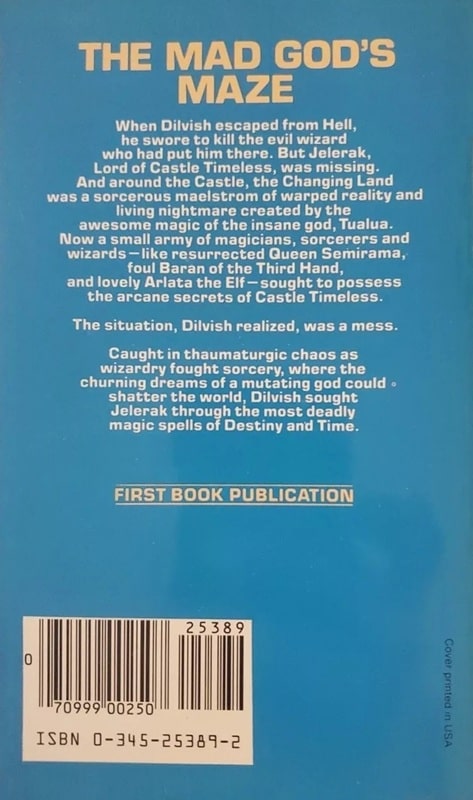

When NESFA Press, that beacon of glory in sf/f publishing, produced its monumental series collecting all of Zelazny’s short fiction (Grubbs, Kovacs, and Crimmins ed.), of course I seized on the volumes as soon as I could, read them through, and loved them furiously.

The Collected Stories of Roger Zelazny, all six volumes (NESFA Press, February – December, 2009). Covers by Michael Whelan

The Collected Stories of Roger Zelazny, all six volumes (NESFA Press, February – December, 2009). Covers by Michael Whelan

There were expected and unexpected pleasures in these volumes, but one of the surprises was how much I liked some of the Dilvish stories, tarnished in my fading memory by that 80s-era read. “I should reread the whole set of Dilvish stories together sometime,” I thought.

That was fifteen years ago, so maybe it’s time.

My executive summary, in case you don’t have the patience to read through these notes, is that the Dilvish stories contain some of Zelazny’s best writing, and some of his worst. My initial, uneasy thought was that the early stories were good and the later stories were bad, but that turned out to be too simplistic; one of the last Dilvish stories he wrote is maybe the single best thing in the two Dilvish books.