https://www.blackgate.com/

Fantastic, August 1961: A Retro-Review

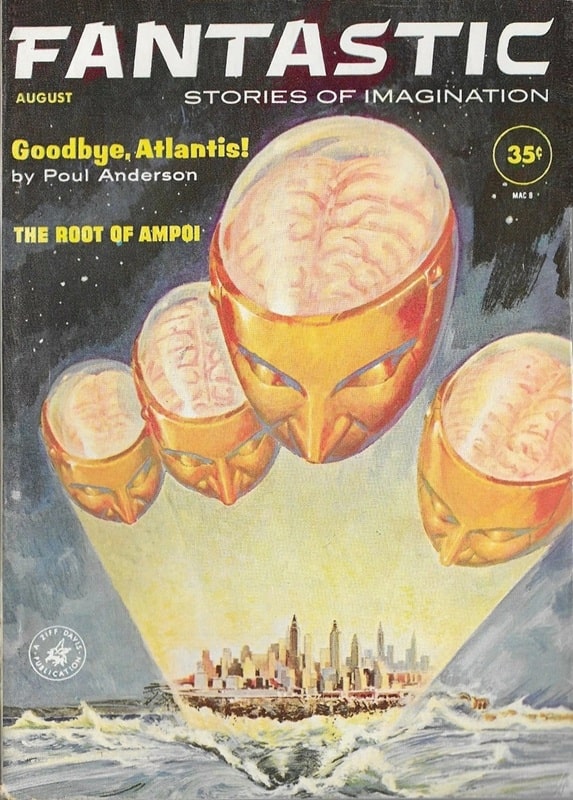

Fantastic, August 1961. Cover by Leo Summers

It’s been a long time since I did a Retro-Review from Cele Goldsmith’s time at Amazing/Fantastic. So I’m happy to be back at it! This issue is from about two years into Goldsmith’s tenure.

There are two features — Norman Lobsenz’s editorial, and the letter column, According to You. (Well, and a brief Coming Soon piece.) The editorial talks about using computers to analyze the various items certain Thais believe have magical powers, ending with a slight joke about hoping to find a love philtre “for Cele.” It introduces the concept by talking about the famous Arthur C. Clarke story in which a computer helps Tibetan monks list all the names of god — but misidentifies the story weirdly by adding another billion names: “The Ten Billion Names of God.”

[Click the images for fantastic versions.]

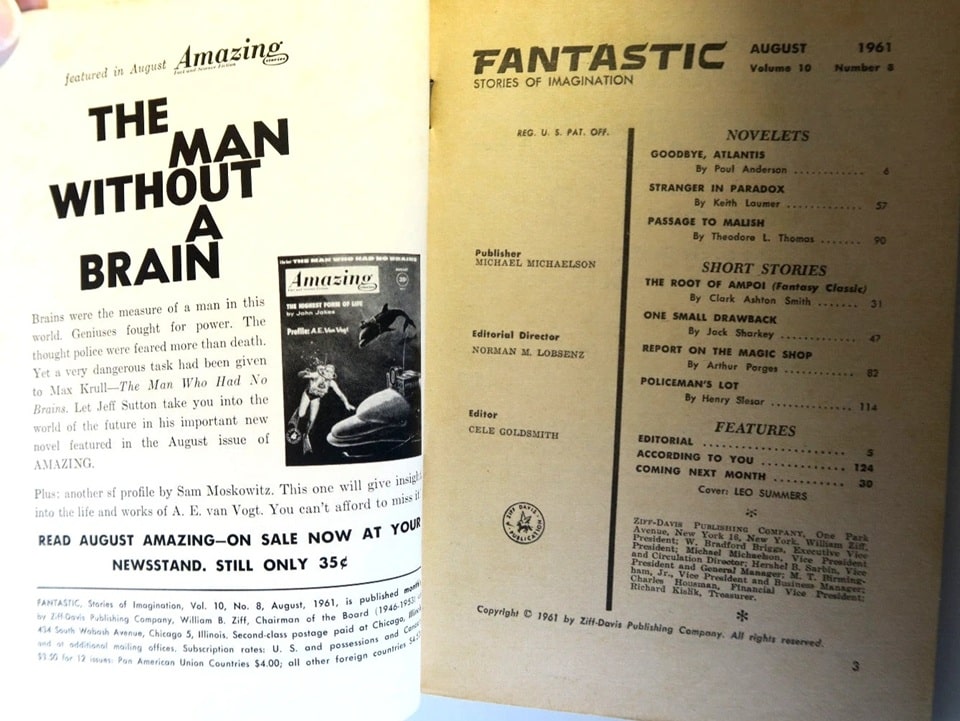

Table of Contents for Fantastic, August 1961

Table of Contents for Fantastic, August 1961

According to You has six letters. I recognized some well-known fans: Bill Bowers and Redd Boggs were both prolific fanzine editors and multiple Hugo nominees. Lawrence Crilly, John Pocsik, and David Charles Paskow are not as was well known but do get mentions in Fancyclopedia 3, and indeed the Paskow Collection at Temple University is named for David Paskow. F. C. MacKnight is the other contributor.

The letters concern mostly Fritz Leiber and the newly instituted use of one reprint per issue — both get praise. David Bunch is of course mentioned — negatively by Bowers and positively by Paskow (the latter mention getting this relieved comment from Goldsmith: “We figured that if we kept publishing [Bunch], somebody sooner or later would agree with us that he has something in his stories.”)

The cover is by Leo Summers, the interiors are by Summers, Virgil Finlay, West, Dan Adkins, and Larry Ivie, with a Summers back cover based on the Smith story, and one cartoon by Frosty.

The stories, then.

Novelets“Goodbye, Atlantis!,” by Poul Anderson (9,000 words)

“Stranger in Paradox,” by Keith Laumer (9,200 words)

“Passage to Malish,” by Theodore L. Thomas (9,000 words)

“The Root of Ampoi,” by Clark Ashton Smith (5,900 words)

“One Small Drawback,” by Jack Sharkey (3,800 words)

“Report on the Magic Shop,” by Arthur Porges (3,000 words)

“Policeman’s Lot,” by Henry Slesar (3,600 words)

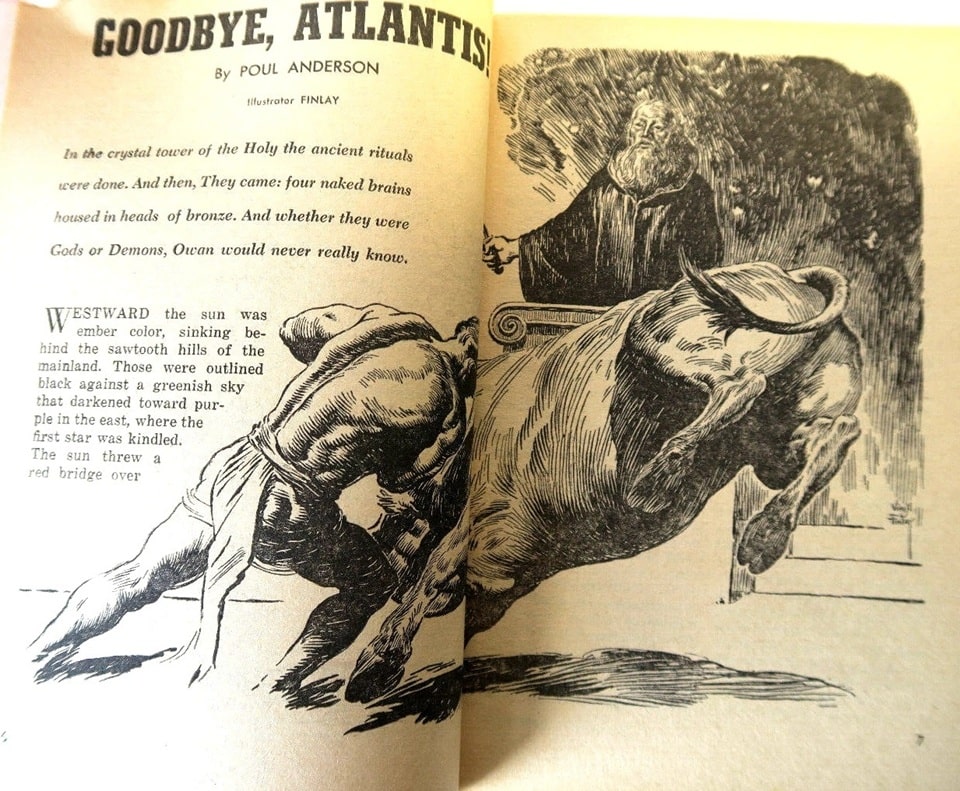

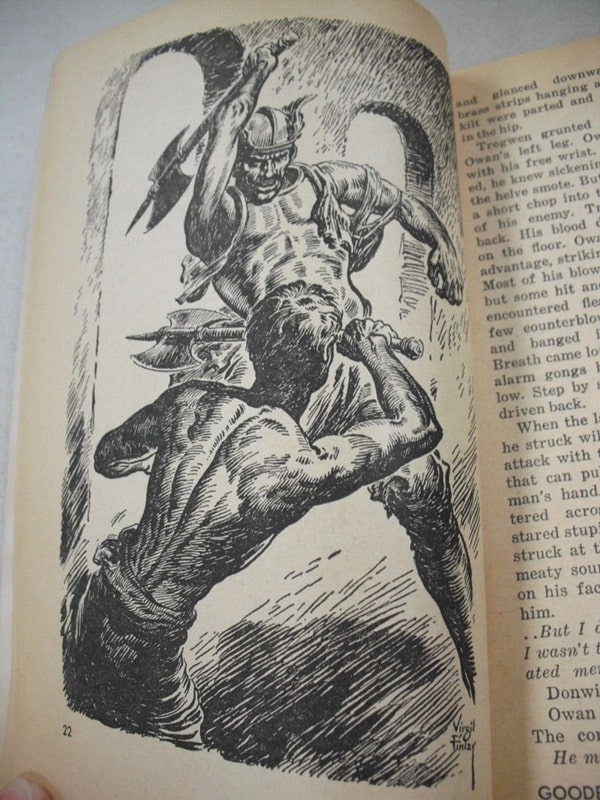

“Goodbye, Atlantis!” by Poul Anderson, illustrated by Virgil Finlay

“Goodbye, Atlantis!” by Poul Anderson, illustrated by Virgil Finlay

“Goodbye, Atlantis!” is a very obscure Anderson story — it’s only ever been reprinted once, in one of Sol Cohen’s super cheap and ugly all-reprint magazines, which mostly or entirely mined the Amazing/Fantastic backlist for material (and reprinted it (legally) without pay until SFWA objected, after which apparently Cohen made nominal payments.)

The lack of reprints is a bit odd, because “Goodbye, Atlantis!” isn’t terrible. It’s no lost classic, but it’s fine. The viewpoint character is Owan, a guard Captain in the retinue of the nobleman Donwirel and his wife Rianna, who is the niece of the former king of Atlantis, and thus cousin to the current king. Owan is in love with the beautiful Rianna, but at this time the concern is that there is a rebellion against the new king.

‘Goodbye, Atlantis!” Illustration by Finlay

‘Goodbye, Atlantis!” Illustration by Finlay

The plot turns on the efforts of the Archpriest Govandon to summon the long absent gods of Atlantis to vanquish the rebels, who are clearly winning the war and have the capitol under siege. Owan has concerns — he doesn’t trust the gods, or perhaps simply doesn’t trust that Govandon’s spells will work. He goes to attend Donwirel, who is working with Govandon — and is poisoned.

It’s clear that Donwirel is a traitor, and only Rianna’s timely intervention saves Owan, after which he struggles to prevent Donwirel from stealing the spells Govandon has learned. There’s some solid action, and Owan (and Rianna) are successful — but their success proves profoundly ambiguous. (Behind it all is a sly suggestion that the rebels were right all along.)

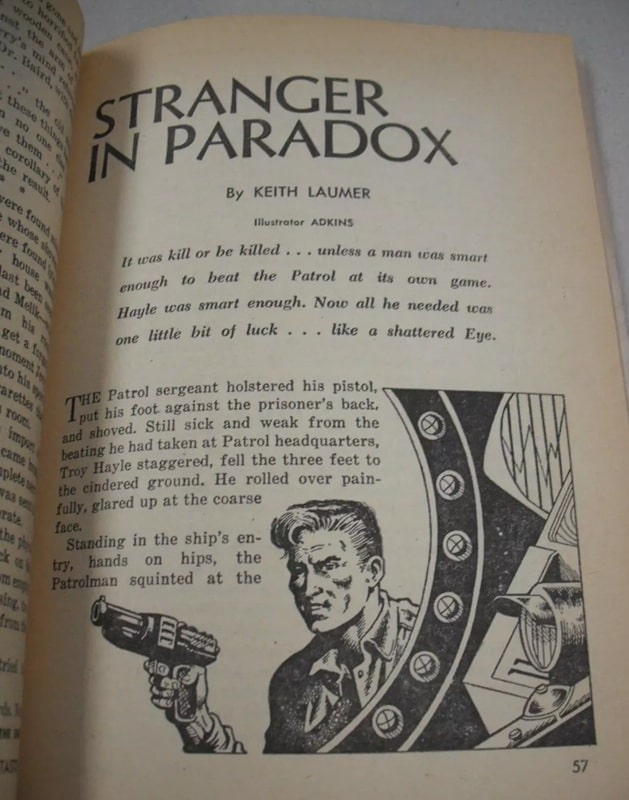

“Stranger in Paradox” by Keith Laumer. Illustrated by Dan Adkins

“Stranger in Paradox” by Keith Laumer. Illustrated by Dan Adkins

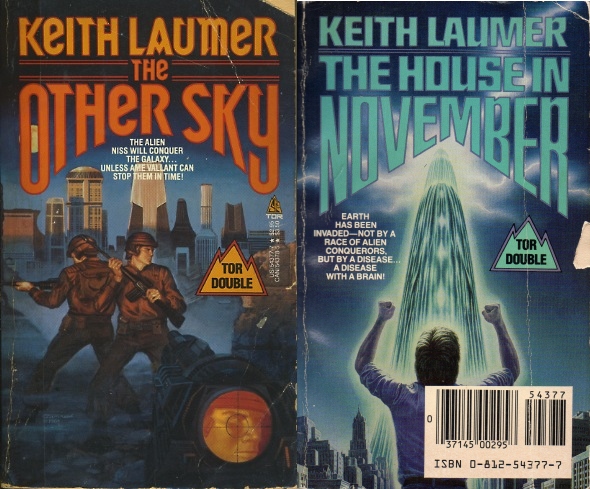

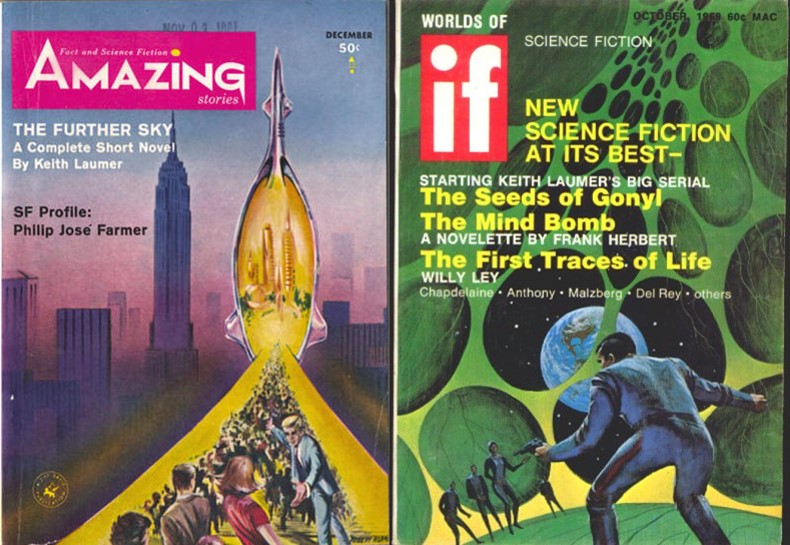

“Stranger in Paradox” was, I think, Keith Laumer’s fourth published story. The first two, “Greylorn” and “Diplomat-at-Arms” were published by Goldsmith as well — Laumer was one of her major discoveries, along with Le Guin, Disch, Zelazny and to some extent Ballard (for the American market.) The Retief stories (after “Diplomat-at-Arms”) ended up finding a home in Frederik Pohl’s If, but Goldsmith otherwise published a great deal of Laumer’s early work.

Alas, “Stranger in Paradox” is pretty awful. Hayle is dumped on the title planet by the Patrol, who seem to be the agents of the despotic rulers of this future. (Details are pretty slight.) They leave him nothing but a short sword and a reusable match. The only rule on Paradox is that prisoners cannot cooperate — they must either avoid each other or fight.

Hayle’s plan is to somehow convince a couple of other people to cooperate, and after figuring out how the Patrol keeps track of the prisoners, he manages that … and then, with a profoundly implausible plot, lots of luck, a woman prisoner falling into their laps, and utterly ridiculous concept of both how the Patrol would work and how they control civilization, they succeed. It’s just dumb dumb dumb the whole way, redeemed only slightly by the fight scenes that are, as usual, quite good — Laumer had the knack of writing fights.

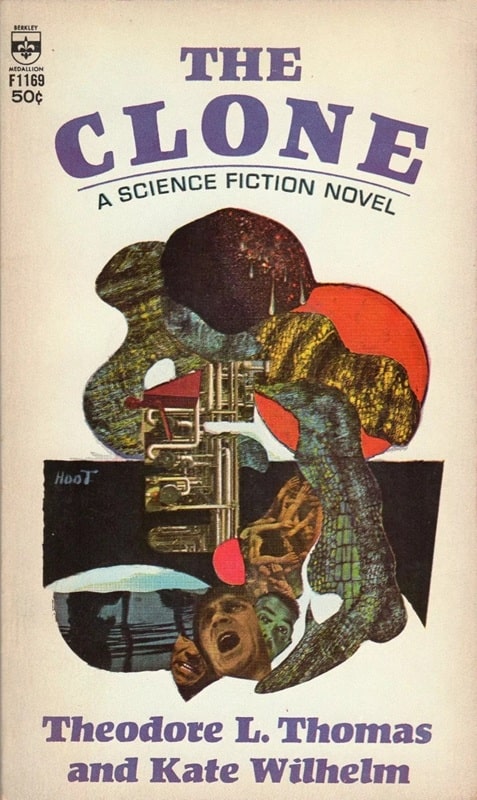

The Clone by Theodore L. Thomas and Kate Wilhelm

(Berkley Medallion, December 1965). Cover by Hoot von Zitzewitz

Theodore L. Thomas (1920-2005) was a chemical engineer and patent attorney who wrote about 50 short stories between 1952 and 1981. He wrote two novels in collaboration with Kate Wilhelm (The Clone and The Year of the Cloud.) He is probably best known still for a series of stories he wrote as “Leonard Lockhard” about science fictional complications with patents — the first two of these in collaboration with fellow patent attorney Charles Harness; and for his story “The Weather Man,” about human control of the weather.

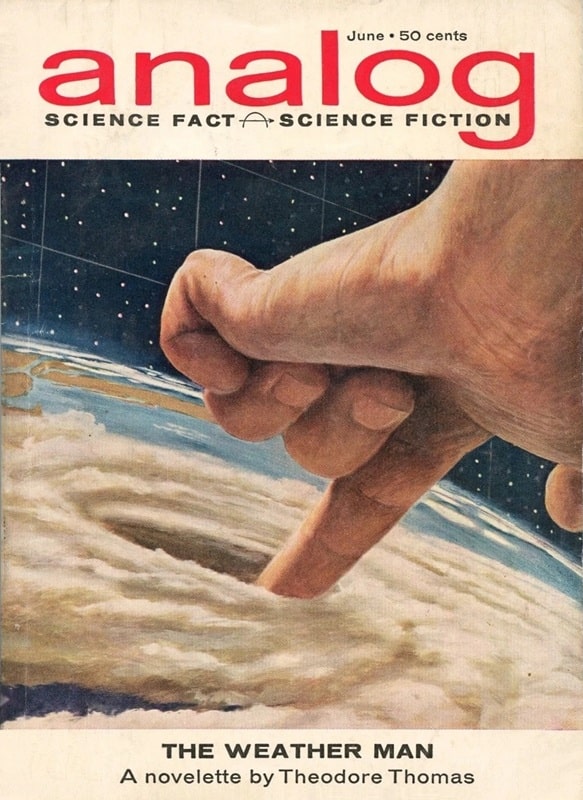

Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction June 1962, containing “The Weather Man” by Theodore L. Thomas. Cover by John Schoenherr

Analog Science Fact/Science Fiction June 1962, containing “The Weather Man” by Theodore L. Thomas. Cover by John Schoenherr

“Passage to Malish” is about a salesman who finds himself diverted from his trip to the planet Malish because it’s been determined that he’s the perfect person to confront the visiting aliens from the Large Magellanic Cloud. The solution involves turning him into a superhuman, committing genocide (or galactocide, I suppose), and then hoping he’ll consent to being turned back to a normal human before he uses his powers to subvert the Milky Way. I never believed any of this story for a second.

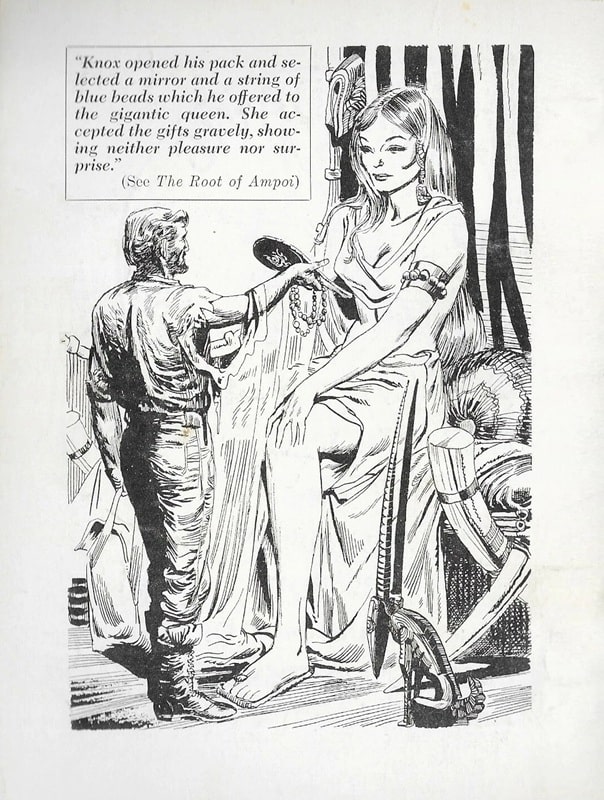

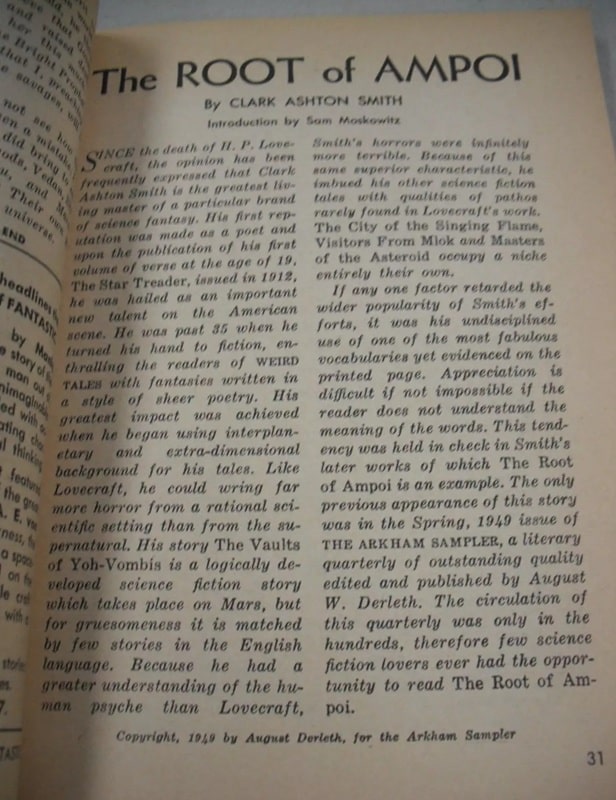

“The Root of Ampoi” by Clark Ashton Smith. Illustration by Summers

“The Root of Ampoi” is Sam Moskowitz’s choice for this month’s fantasy reprint. Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961) was a poet and a writer of weird fiction whose reputation has gone up and down over time, and seems on the upside now. He was a regular contributor to Weird Tales, and part of Lovecraft’s circle. He was known for his ornate prose and extravagant imagination, so, Moskowitz, with his impeccable as ever taste, declaring in more or less Salieri mode that Smith used “too many words” (that’s my paraphrase of Moskowitz’ words) chose a completely uncharacteristic story to reprint. (That said, it has been reprinted fairly often, one time as “The Ampoi Giant,” so other people may disagree with me.)

“The Root of Ampoi” is a tale told by a giant working for a circus. He was a sailor, and he heard of a place on New Guinea where the men were normal sized and the women were nine feet tall. And there were rubies to be had for a song. Seeking to make his fortune, he finds this place, and learns about the secret that makes the women so tall — after the queen of those women chose him for a consort. But, unhappy with being dominated by a much larger wife, he ferrets out the secret… the punishment for which is banishment. No rubies either. But — easy to find circus work. This is really minor stuff — a competently executed tall tale, really. But it seems nothing like a real introduction to CAS.

Jack Sharkey (1931-1992) was a Cele Goldsmith regular, though to my taste he was a pretty weak writer. “One Small Drawback,” however, is not too bad at its length. Jerry, a college kid, is intrigued by his professor’s research into telekinesis, but nothing he tries has any effect. His professor is convinced that what he needs is true belief. Then something small happens that convinces Jerry he can use telekinesis… but it doesn’t work consistently. The key element he eventually discovers is pretty clever, and effectively dark.

Arthur Porges (1915-2006) wrote over 200 stories, split roughly 50/50 between mystery and SF. His stories were mostly fairly short, and were consistently clever, sometimes amusing, sometimes quite mordant. As a writer of exclusively short fiction, he’s not really widely remembered, but he was one of the most dependably enjoyable writers in the field, and his contributions appeared right up until his death, mostly in F&SF but also in Goldsmith’s magazines. “Report on the Magic Shop” is good solid fun, nothing earth-shattering, written as if the author is telling the editors about the various products sold at a magic shop he happened to stumble into.

“Policeman’s Lot” by Henry Slesar. Illustration by Summers

“Policeman’s Lot” by Henry Slesar. Illustration by Summers

Henry Slesar (1927-2002) was another writer of both SF and crime fiction, with most of his SF fairly short. He was better known as a mystery writer, and so perhaps it isn’t a surprise that “Policeman’s Lot” is basically a mystery, though with a fantastical solution.

A veteran patrolman submits a report on a strange case he recently investigated, involving a couple of basically “locked room” thefts, in which in one case a man was found escaping from a window naked. Not long after, the man is found crushed to death in his house. The strange factor is that he seems to have changed height between separate arrests. The solution is kind of obvious, and acceptable except as an explanation of his death.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was We Are Missing Important Science Fiction Books. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over 200 articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Movie of the Week Madness: Duel

Can anyone dispute Steven Spielberg’s title as the most successful motion picture director of all time? Not if you’re talking box office, you can’t. As of June, 2024, Spielberg’s films have grossed almost eleven billion dollars, putting him two billion ahead of his nearest competitor, James Cameron, and as Randy Newman sang, it’s money that matters. In Hollywood that’s probably truer than anywhere else in the world, and the profits generated by Spielberg’s many successes have more than made up for the losses incurred by his rare failures, making the suits very, very happy.

What about recognition from colleagues and critics? He has been nominated nine times for Best Director, winning twice (for Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan), and he received another Oscar as the producer of Schindler’s List when that film won Best Picture. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (you can step on him at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard), has won the Academy’s prestigious Irving Thalberg Award (are there any awards that aren’t prestigious?), and has received more honors from various cinematic guilds and organizations than can easily be counted.

This storied career had its humble beginning in television in 1969, when Spielberg directed an episode of Rod Serling’s Night Gallery, and through the early 70’s he directed episodes of various other television shows, including the very first episode of Columbo, Murder by the Book. (And yes, I know about Prescription Murder and Ransom for a Dead Man, but technically those are stand-alone TV movies, not episodes of the series.)

And speaking of TV movies, Spielberg also directed three segments of the ABC Movie of the Week, one of which still stands as arguably the best made-for-TV movie ever. I’m talking, of course, about Duel.

The ABC Movie of the Week ran for six seasons between 1969 and 1975, featuring original made-for-television fare from all genres, and the mere thought of the show can make many people of my age fall to the floor in a swoon, regaining consciousness with visions of Barbara Eden dancing in our heads and the scent of Kraft Mac and Cheese lingering in our nostrils. It’s only when we lift our faces from the carpet and see that it isn’t burnt-orange shag that we realize it’s not 1972.

Most of these “world premier” movies ranged from the merely forgettable (Gidget Gets Married) to the utterly schlocky (Satan’s School for Girls) to the absolutely godawful (The Feminist and the Fuzz). In other words, they were nothing to write home about, especially when seen from the distance of half a century (we had far fewer options in the 70’s, so when the trainer threw us a fish we clapped our flippers and snapped it up, fresh or not), but some MOWs were better than that, and at the pinnacle are a bare handful that still hold up, even when viewed with eyes unclouded by cataracts or nostalgia.

None of them stand higher than Duel, which was broadcast on Saturday, November 13, 1971. Directed by a twenty-four-year-old Steven Spielberg and scripted by the great Richard Matheson from his own short story, it’s the rare product of its era that can hit an unsuspecting viewer of today almost as hard as it did its original audience. (I’m sure it’s not a coincidence that Richard Matheson wrote two more of the best ABC MOWs, Trilogy of Terror and The Night Stalker.)

Duel begins in the most prosaic fashion imaginable, with salesman David Mann (Dennis Weaver) backing his red Plymouth Valiant out of his modest suburban garage and heading north for an important meeting with a client; almost all of the first five minutes of the film are through-the-windshield POV shots of the early stages of Mann’s journey. We see him motor up CA 5 through Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley; eventually traffic thins out as he enters the intermediate region where upper Southern California gradually morphs into lower Central California. Soon almost all other traffic vanishes as Mann leaves the 5 and swings north-east, continuing into the Mojave Desert on smaller, two-lane highways. (Just what he could be selling to anyone in this bleak, post-apocalyptic landscape is never addressed. Geiger counters, maybe?)

It is on an empty stretch of one of these roads that the duel begins, without Mann at first even realizing it. He comes up behind a massive, dirt-encrusted, smoke-spewing tanker truck (a 1957 Peterbilt 281, chosen by Spielberg for its menacing “face”), and not wanting to be late for his meeting, Mann passes it. The truck immediately shows its displeasure by aggressively passing Mann to regain the lead, angrily blowing its horn as it goes by. Increasingly worried about falling behind schedule, Mann repasses the tanker and puts on speed in the hopes of leaving this annoyance behind.

I said the truck shows displeasure rather than the driver because all we ever see of the human operator is part of his left arm (and briefly, his cowboy boots). Nothing else is visible behind the vehicle’s filthy, sun-glared windshield, while the enormous, threatening body of the truck and its “voice” — the bellow of its horn, the roar of its engine, the threatening hiss of its hydraulics — are omnipresent. Turning the truck itself into the antagonist was a deliberate choice by Matheson and Spielberg, making Duel truly a story of Mann vs. Machine.

David soon stops at a service station to get some gas and to call his wife. While he’s still sitting in his car waiting for the attendant (remember those?), the truck pulls in beside him. For a moment, the salesman visibly shrinks back in his seat, fearing trouble, but all he ever sees of the driver, who gets out on the passenger side and stays on the far side of the truck, hidden behind the tank, are his cowboy boots. Soon the attendant shows up and checking under the hood, tells Mann he needs a radiator hose. “I’ll get it later”, David says, and when the attendant replies, “You’re the boss”, Mann mutters under his breath, “Not in my house, I’m not.” (This is what is known as a significant subtext.)

He goes inside and calls his wife, apologizing for an argument they had the night before about an incident that had happened at a party, when a friend apparently got a little too familiar with Mrs. Mann. David’s response to this was not nearly as strong as his wife wanted; the increasingly acrimonious conversation makes it clear that she thinks that her husband is not living up to his responsibility as a protector. The frustrated suburbanite doesn’t think slighting his manhood is fair — “You think I should go out and call Steve Henderson up and challenge him to a fistfight or something!” The call ends with the pair more displeased with each other than when it began.

Angry and humiliated, Mann resumes his drive, and it isn’t long before the truck reappears. The contest is just beginning.

Over the next several miles, the incidents accumulate and escalate until it begins to dawn on Mann that he has left the comfortable, predictable precincts of suburban normalcy behind and entered a raw realm where the only law is survival of the fittest, which is not a place anyone would want to bring a Plymouth Valiant. (Could any model have been more ironically named?)

After leaving the gas station, the truck quickly passes the Valiant, and then keeps the agitated Mann from passing by moving side to side to block him, until an arm extends out of the truck’s window and motions David to pass, which he does… but he has been waved into a head-on collision with an oncoming pickup truck, which he is barely able to avoid. It could not have been an accident. The truck has deliberately tried to kill him.

Soon the tanker is dangerously crowding David, coming up fast from behind, forcing him to increase his speed, until he finally loses control of the car and veers off the highway, coming to a stop after crashing through a wooden fence as the truck roars past. Staggering into a nearby roadside diner, the shaken salesman makes his way into the bathroom, where he slumps over the sink and attempts to recover his composure. In a voice-over, we are privy to Mann’s thoughts, which distill the whole movie into a few lines (Weaver has almost all of Duel’s dialogue, in voice-over or spoken aloud to himself in the car):

Well, you never know. You just never know. You just go along figuring some things don’t change, ever. Like being able to drive on a public highway without somebody trying to murder you… and then one stupid thing happens. Twenty, twenty-five minutes out of your whole life, and all the ropes that kept you hangin’ in there get cut loose. And it’s like, there you are, right back in the jungle again. All right boy, it was a nightmare, but it’s over now. It’s all over.

Walking out of the restroom, Mann looks out of the diner’s wide front window and sees the truck, parked right outside, implacably waiting for him. He’s still in the jungle, and his nightmare is far from over.

Sitting around the room are a half dozen beefy trucker types, and every damn one of them is wearing cowboy boots. Deciding that one heavy-looking fellow sitting in a booth nursing a beer is his tormentor, David walks up and starts remonstrating with the trucker, telling him to stop the harassment and threatening to call the police if he doesn’t.

The Opponents

When the baffled trucker says he has no idea what Mann is talking about, David, who is visibly shaking with tension and anxiety, flares into a rage and slaps the beer out of the man’s hand, provoking the guy to jump out of the booth and beat the crap out of him. When the dazed Mann looks up from the floor, he sees the burly teamster storm out of the diner and climb into… a different truck. A moment later, the tanker pulls out and heads up the road; the driver was never in the diner at all. After a few minutes, Mann leaves the building and follows hopelessly.

The contest continues, as a desperate Mann tries every way he can to bring it to an end.

Trying to speed ahead of the truck in the hopes of getting away doesn’t work — in fact it almost proves fatal when Mann has to stop for a train at a railroad crossing and the truck comes up from behind and tries to push the Valiant into the path of the speeding locomotive. Terrain briefly seems to come to Mann’s rescue when he gets to an uphill grade; seeing his opportunity, David puts on all the speed he can, sending his much lighter vehicle flying up the hill, while maniacally chanting, “You can’t beat me on the grade! You can’t beat me on the grade!!” The grade runs out quickly, however, and Mann is right back where he started.

Calling the police doesn’t work — Mann pulls off at one of those ubiquitous (or they used to be, anyway) desert roadside attractions (visit the Snakearama!) and gets in a phone booth, but before the operator can connect him with the authorities, the truck barrels into the booth and demolishes it, with Mann barely escaping in time. (We see the truck coming; Mann, intent on his call, doesn’t. The timing couldn’t be any narrower, and for a hair-raising instant, we think, “My God, Dennis Weaver is going to get killed making a freakin’ ABC Movie of the Week!!”) The truck then pursues him around the Snakearama lot, casually destroying displays holding snakes and spiders and other nasty Southwest critters. (At one point, David barely avoids being bitten by a rattler and has to knock a tarantula off his leg before scrambling back into his car and fleeing. The once thoroughly-domesticated salesman is truly back in a world red with tooth and claw.)

Parking for an hour and waiting for the truck to leave him behind doesn’t work; his antagonist is waiting for him when he resumes his journey. (Oddly, Mann never considers just turning around and going home. This client he’s going to meet must have a hell of an account. Or maybe he’d just rather face the truck than his wife.)

Flagging down a passing car and asking for help doesn’t work; the nervous, elderly couple that David manages to stop are quickly run off by the truck. (The wife was against getting involved anyway.)

Finally, as the Valiant and the truck are racing down a series of twisty side roads, the inevitable happens — the radiator hose that Mann was warned about blows. The car begins to overheat and the engine starts to thump and shudder, and through blood-smeared lips and teeth (during all the jolting and jouncing he has badly bitten his lip) David Mann ignores the Deity that he likely gave little thought to anyway, back when the biggest trial he faced was mowing the lawn or making a sales pitch. Instead, in the last extremity, he frantically talks to the car itself, pleading, screaming, weeping, begging it for just a little more speed.

Mann gains a little distance when he comes to a place where he is able to coast down one side of a hill while the truck is still climbing the other side, and it is here that the Valiant rolls into a dead end, with the road that the truck will momentarily appear on behind David and a cliff in front of him. This is the end of the line; unless he can think of something, David Mann will be dead in a few minutes. The businessman has been defeated at every point… but in the jungle, the savage knows what to do.

Mann turns the Valiant so that it will be facing the truck when it arrives, and when it does, he finally takes the offensive and drives at the killer head-on. (The way Spielberg shoots the scene makes you think of two jousting knights charging at each other in a tourney.) Jamming the accelerator to the floor with his briefcase, Mann jumps out just before the vehicles collide. The Valiant jams up underneath the front of the truck and explodes; blinded by smoke and flame, the still-faceless driver is unable to brake or downshift rapidly enough to keep the truck from going over the cliff, which it does in slow-motion, with deafening, almost dinosaur-like shrieks and bellows and groans coming from its tortured metal body.

Mann rushes up to the brink, looking down at the wreckage below. He watches as one of the truck’s huge wheels turns slower… and slower… and finally stops. There is no more movement, no more sound. The Monster is dead.

The last paragraph of Richard Matheson’s story describes what happens next:

Then, unexpectedly, emotion came. Not dread, at first, and not regret; not the nausea that followed soon. It was a primeval tumult in the mind: the cry of some ancestral beast above the body of its vanquished foe.

David Mann, civilized, suburban husband and father, the proud possessor of a good job and a nice house and (when the day began) a shiny mid-size American car, shrieks and capers along the edge of a cliff, dancing a frenzied dance of victory, singing a wordless song over the shattered corpse of his adversary.

The last shot of Duel shows Mann sitting on the brink of the chasm, utterly drained, silently tossing pebbles into the abyss as the sun goes down behind him. He will likely sit there all night. What will he do when the sun comes up in the morning? Will he just get up and walk away? Is there anything to go back to?

Certainly, the rising sun will light a different world than it did the morning before, when Mann left his sleeping wife and backed out of his garage, and if he does go back home, I suspect that handsy Steve Henderson had better watch out…

Duel is (forgive me) a smashing piece of work, and after fifty years of achievement at the highest level, it’s still one of the best things that Steven Spielberg has ever done. (Apparently he agrees — he has said that he watches it a couple of times a year.)

First praise goes to Richard Matheson for laying such a solid foundation. His script is all essentials; pared to the bone, it really moves, especially in Duel’s original broadcast version, which ran only seventy-four minutes. (The movie was so successful with the audience and critics that the studio quickly had Matheson write some additional scenes, and Spielberg shot another fifteen minutes so that Duel could get a limited theatrical release.)

The terror springs from the believability of the situation, from its very ordinariness, which was always Matheson’s trademark. (He based Duel on an encounter he actually had with a truck on a California highway on November 22, 1963, the day President Kennedy was shot.) Who hasn’t thought about how isolated and vulnerable we are in our little metal boxes when we’re out in the middle of nowhere? There are times when if civilization is no more than a half-hour away, it might as well be on the far side of the moon, and if we were called on to be our own last resource in a life-or-death situation, how many of us would be up to it?

Then, Steven Spielberg’s direction does full justice to the possibilities in this rich scenario. At twenty-four years old, he already seems a master; there is nothing slack, uncertain, or clumsy, only relentless, constantly escalating tension that’s so perfectly, mercilessly staged that when this harrowing movie is over, you’ll have to take a valium and lie down after wringing out your sweat-soaked clothes.

Because we’re with the story’s protagonist every minute, an extra-large burden is placed on Duel’s leading man, and Dennis Weaver carries that load with ease. He is completely believable in every moment of confusion, frustration, fear, panic, hope, despair and exultation. One false note could have destroyed the whole character, but there are no false notes, and when it’s time to go over the top, Weaver effortlessly carries us over the top with him. It’s a great performance.

Duel has one last excellence that I can’t fail to mention — the stunt driving. The delight of watching a pre-CGI action film with nothing but practical effects is hard to overstate. What with Bullitt, The French Connection, The Rockford Files, Mannix and the countless other police and detective yarns that dominated television and movies in that era, the 60’s and 70’s were the glory years of car chases and car crashes.

Duel is practically an encyclopedia of car stunts (Weaver’s driving double was the great Dale Van Sickel), and the high-speed swerves, skids, fishtails, scrapes and hairbreadth near-misses will have you ducking, flinching, and yelping in a way that the whole Fast and Furious franchise couldn’t manage over the course of ten entire (and entirely silly) movies.

So do yourself a favor — install seat belts on your couch and watch Duel. You’ll experience the pulse-pounding pleasures of terror and savagery and triumph right in the comfort of your own safe and civilized living room, and when it’s over, you’ll thank Richard Matheson, Steven Spielberg, Dennis Weaver, the ABC Movie of the Week and me.

And one more thing — if you plan on ever leaving that living room to venture into the unpredictable world outside, take the advice of someone who once worked in auto service: stop fooling around and get your belts and hoses replaced. Your life may very well depend on it.

Always Trust Your Gas Station Attendant

Always Trust Your Gas Station Attendant

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Metaphysical Nightmare: Brian Moore’s Cold Heaven

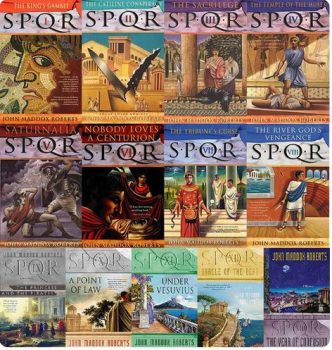

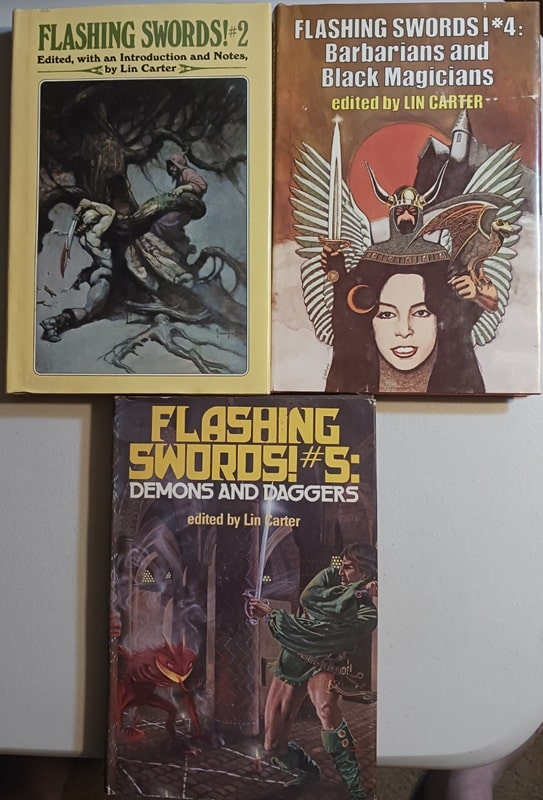

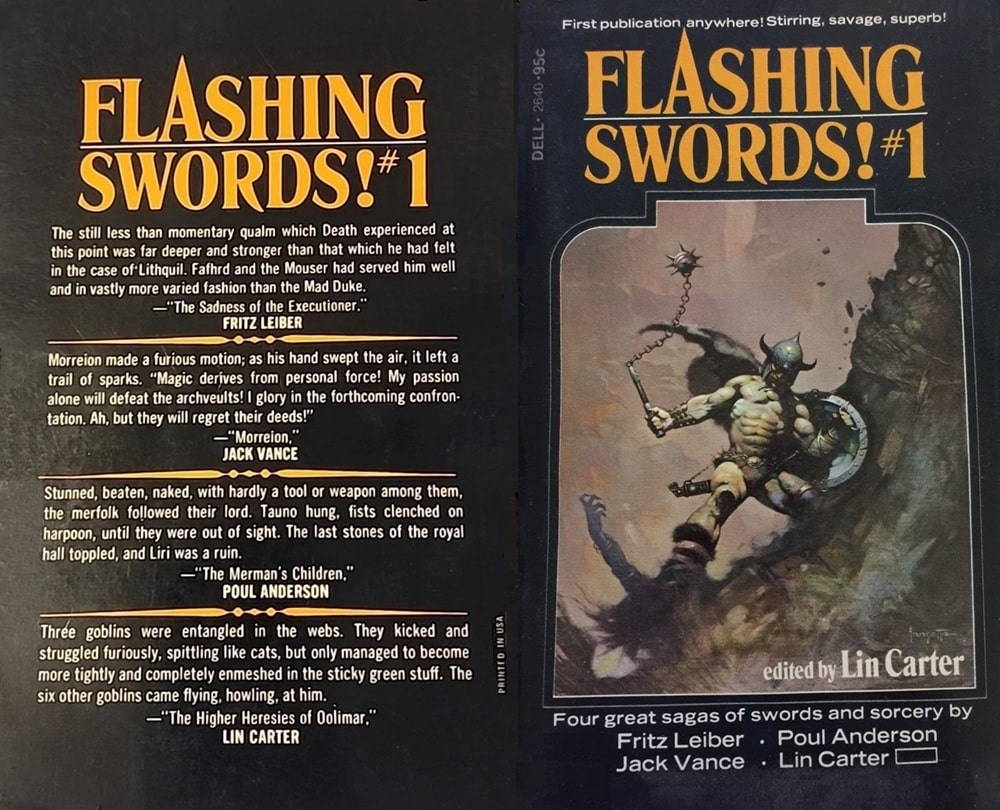

A Sword & Sorcery Series I Really Love: Flashing Swords!, edited by Lin Carter

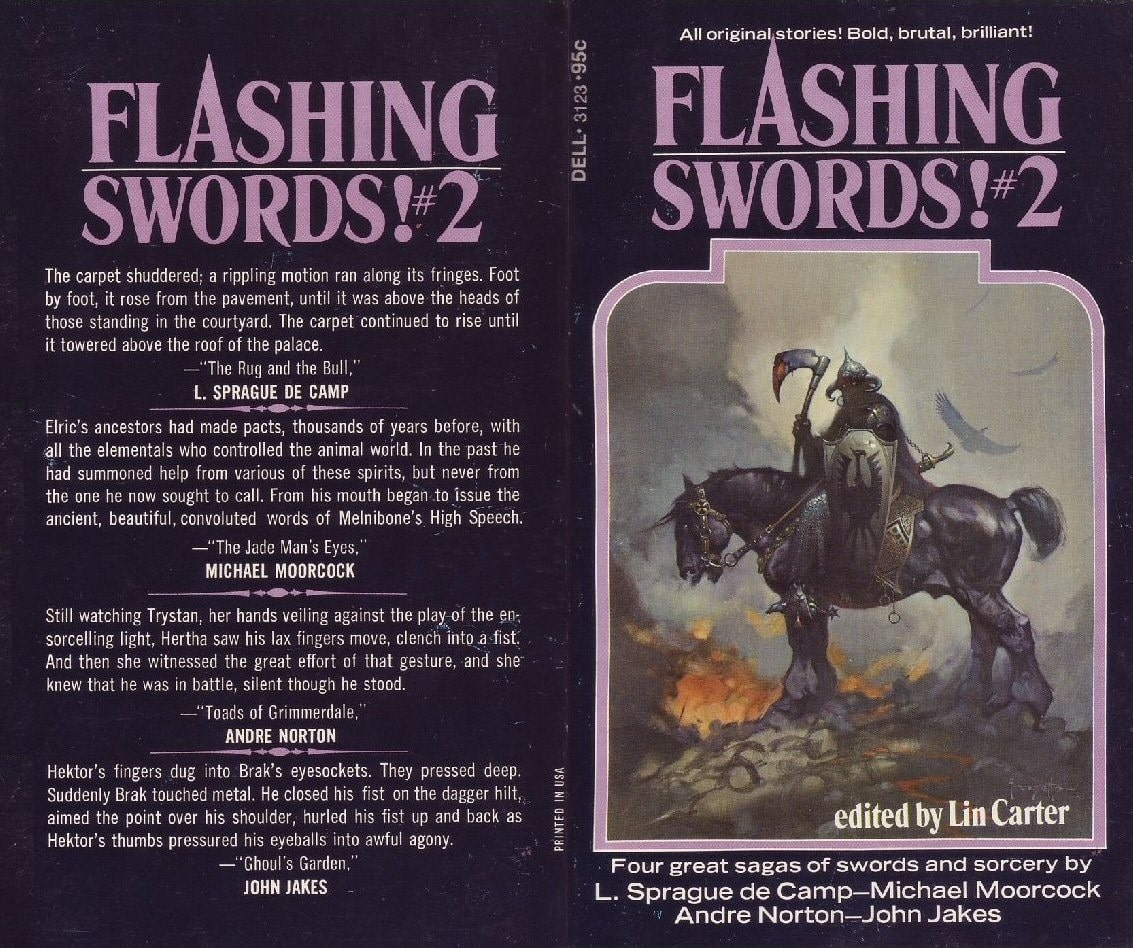

Flashing Swords! #2, 4, & 5 (Science Fiction Book Club, September 1973, May 1977,

and December 1981). Covers by Frank Frazetta, Gary Viskupic, and Ron Miller

It’s time to take a look at another Sword & Sorcery anthology series I really love: Flashing Swords, edited by Lin Carter. It is second in my affections only to the Swords Against Darkness 5-book series edited by Andy Offutt that I wrote about here last year.

Flashing Swords! came out of the group known as SAGA, which stood for the Swordsmen and Sorcerers Guild of America, a group in the 1970s and 80s that included almost all the elite S&S writers of the age.

They were an informal group but Lin Carter was the closest thing they had to a leader. Under his editorship, five outstanding anthologies of works from their members appeared, all new stories, not reprints. As shown in the pictures below, I have the volumes from Dell paperbacks, as they were originally released, and three from Nelson Doubleday in hardback (above), as they were offered by the Science Fiction Book Club.

[Click the images for flash versions.]

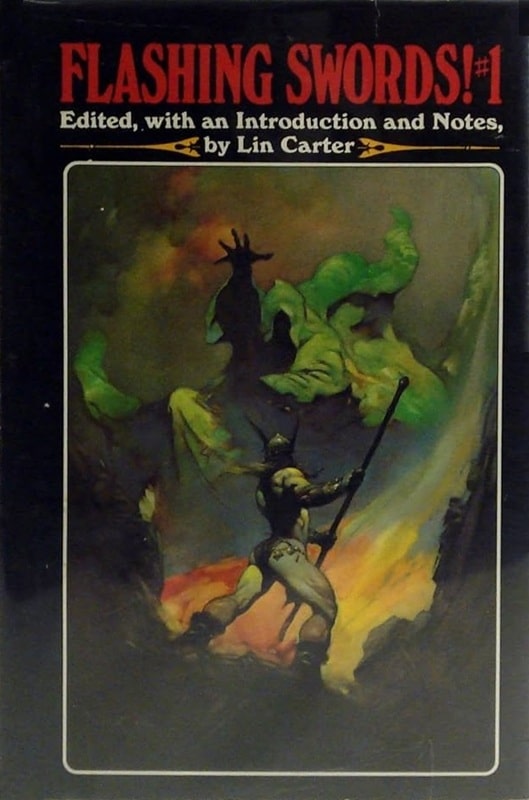

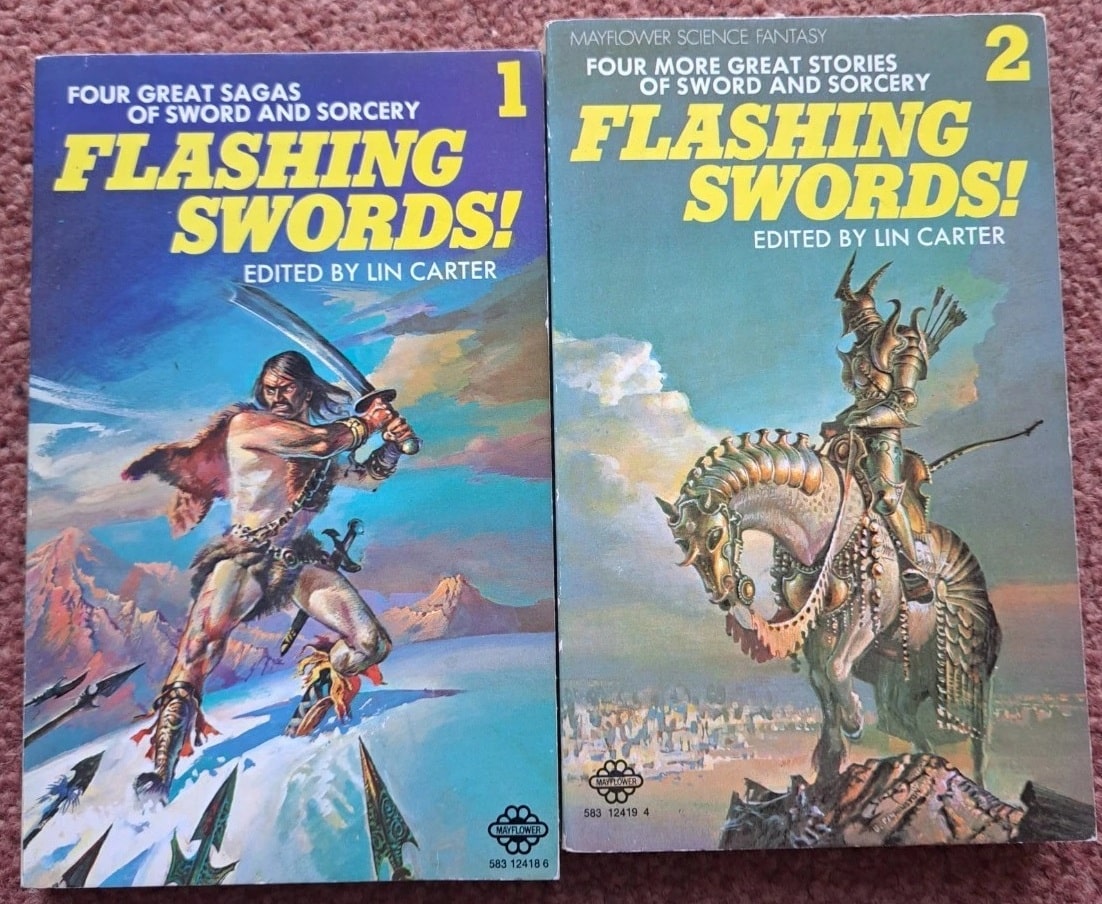

Flashing Swords #1 (Dell, July 1973). Cover by Frank Frazetta

Flashing Swords #1 (1973) has 4 longish stories by Leiber, Vance, Anderson and Carter. All were strong and this is probably the strongest of all the volumes. Anderson’s story, “The Merman’s Children,” is the best, and Carter’s story, “The Higher Heresies of Oolimar,” is one of his strongest ever.

The cover was an awesome Frazetta, one of my favorites of his paintings behind his Kane and Death Dealer art. The volume was dedicated appropriately to Robert E. Howard.

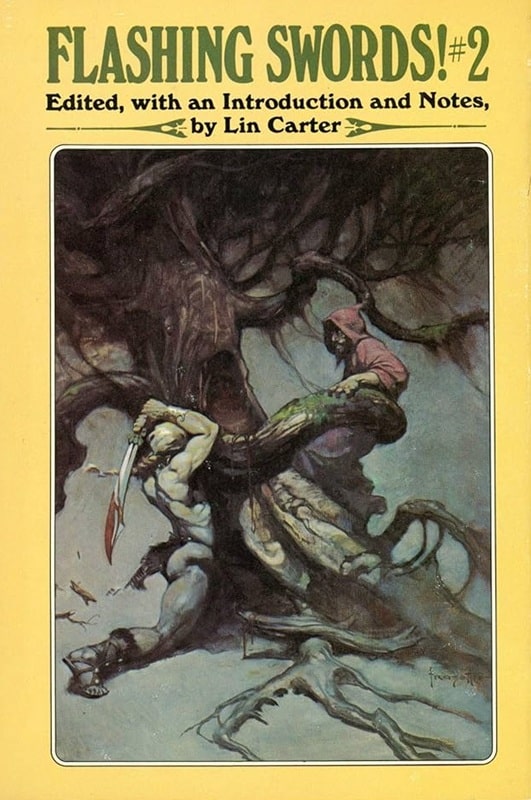

Flashing Swords! #2 (Dell, April 1974). Cover by Frank Frazetta

Flashing Swords #2 (1973) is dedicated to Henry Kuttner. It had four more long stories, by L. Sprague de Camp (with whom Carter had a long history), Michael Moorcock, Andre Norton, and John Jakes.

Moorcock’s story, “The Jade Man’s Eyes,” was of Elric, and Jakes’ story, “Ghouls Garden,” was about his character Brak. I’ll talk more about both authors eventually here but both these tales were very good and I particularly loved the Brak story, which made me seek out more of the tales.

Flashing Swords #1 & 2, UK editions (Mayflower, 1974 and February 1975). Covers by Bruce Pennington

The hardback has a great Frazetta cover, but have a look, too, at the paperback cover from Mayflower books (above), which I found online. I like that one even better than the Frazetta I think, although that sounds almost blasphemous.

Bruce Pennington did it and I wish I had that edition.

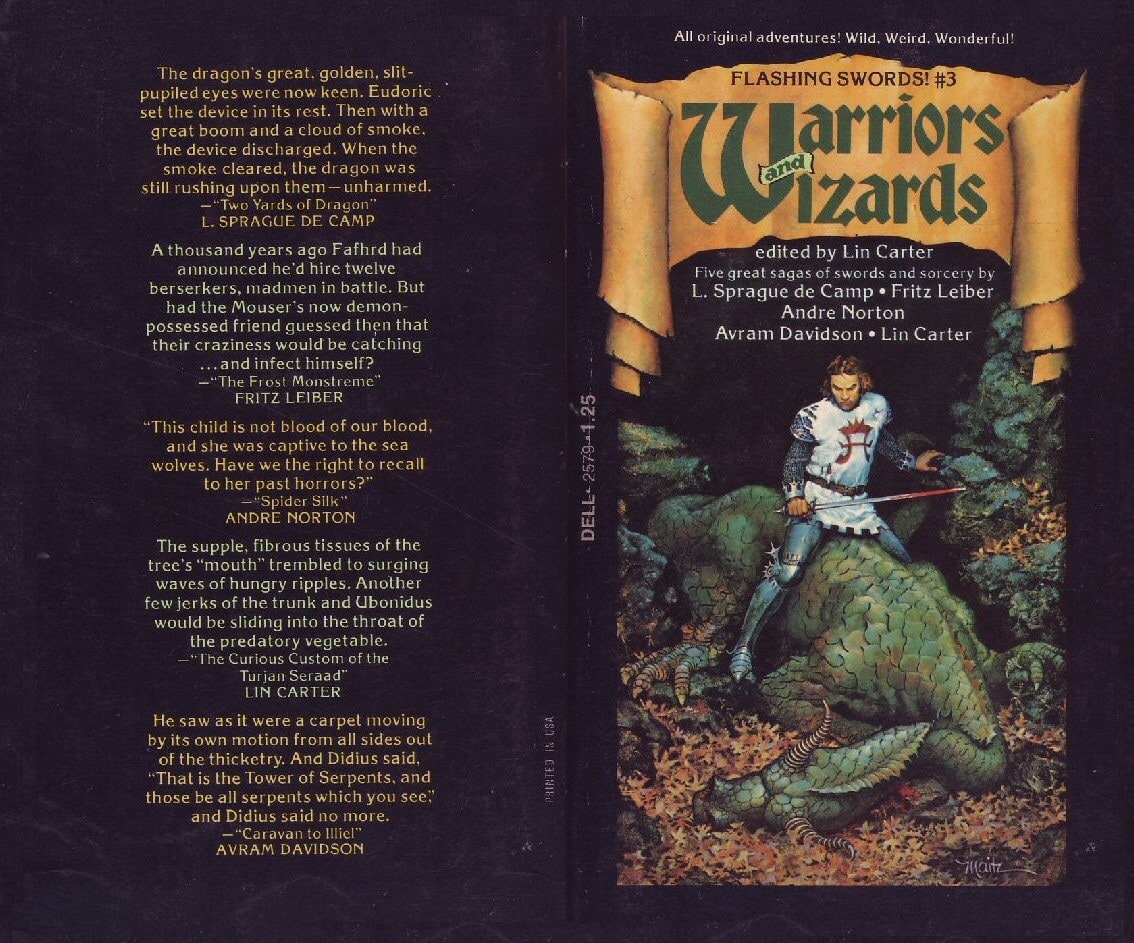

Flashing Swords! #3: Wizards and Warriors (Dell, August 1976). Cover by Don Maitz

Flashing Swords #3 (1976) bore a subtitle, Warriors and Wizards. It was dedicated to Clifford Ball. This was the weakest of the five volumes, although still good. It had stories by de Camp, Fritz Leiber, Andre Norton, Carter, and Avram Davidson.

The Leiber story, “The Frost Montreme” — Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser — was the strongest. Don Maitz is the cover artist. It’s good, but a bit less barbaric than I like. Very Renaissance looking.

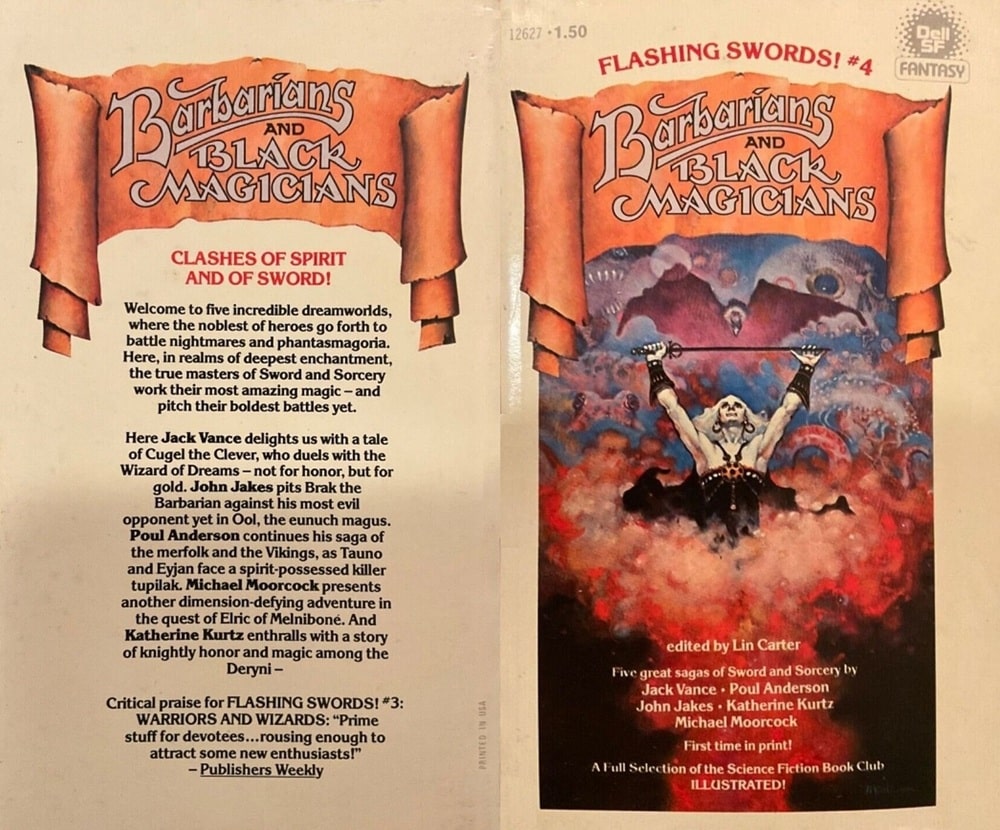

Flashing Swords! #4: Barbarians and Black Magicians (Dell, November 1977). Cover by Don Maitz

Flashing Swords #4 (1977) is subtitled Barbarians and Black Magicians. This one is dedicated to Norvell Page, who I’ll be covering here. Stories by Vance, Anderson, Jakes (Brak; Storm in a Bottle), Katherine Kurtz, and Moorcock (Elric; “the Lands Beyond the World”).

This one is as strong as the original volume, and I like the hardback cover by Gary Viskupik. It also has some cool interior illos by Rick Bryant. The paperback cover, which I found online, is by Don Maitz again and looks like an Elric representation.

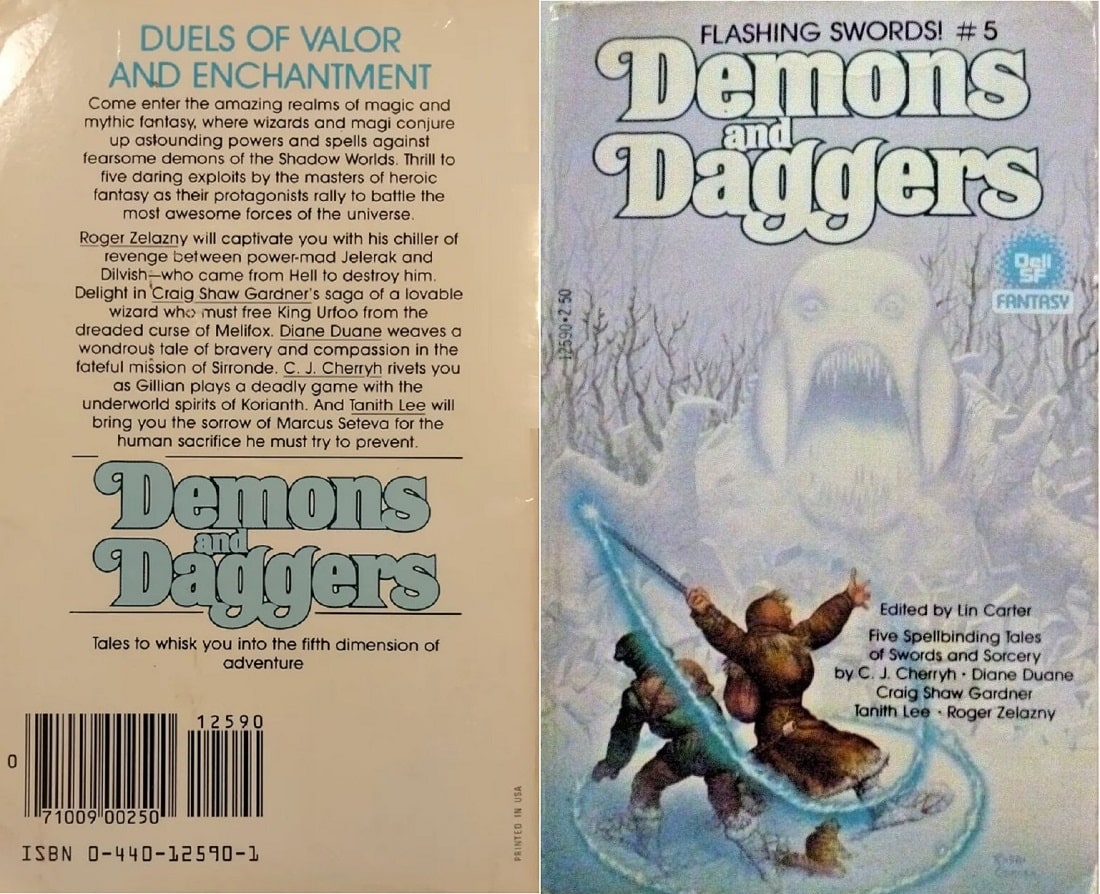

Flashing Swords! #5: Demons and Daggers (Dell, December 1981). Cover by Rich Corben

Flashing Swords #5 (1981) is subtitled Demons and Daggers. No dedication. It has a cool wraparound cover by Ron Miller, although it’s my least favorite of the series. The Dell paperback has a cover by Richard Corben.

Includes stories by Roger Zelazny (a Dilvish tale), C. J. Cherryh, Diane Duane, Tanith Lee, and the first humorous story in the series by Craig Shaw Gardner. I didn’t think it was as strong as #1, #2, or #4, but somewhat better than #3.

Flashing Swords! #1 & 2 (Science Fiction Book Club, April and September 1973). Covers by Frank Frazetta

In 2020, Robert Price, Lin Carter’s literary executor, revived the series as Lin Carter’s Flashing Swords. There have been two volumes published, although the first one created a minor storm of controversy over the introduction by Price. I have not yet bought or read these two volumes.

I’ve also included above the hardcover covers for volumes 1 and 2 (above), both by Frazetta.

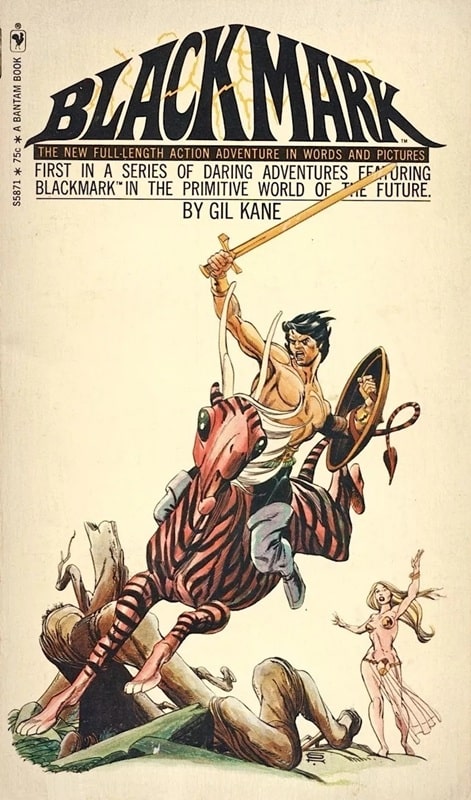

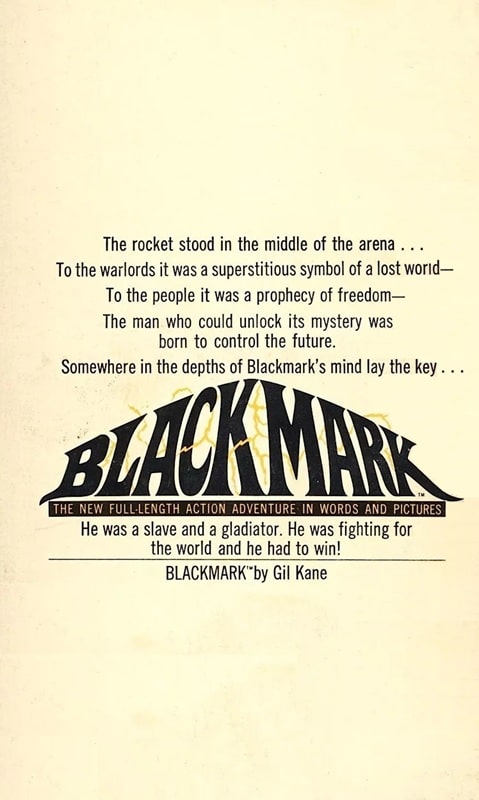

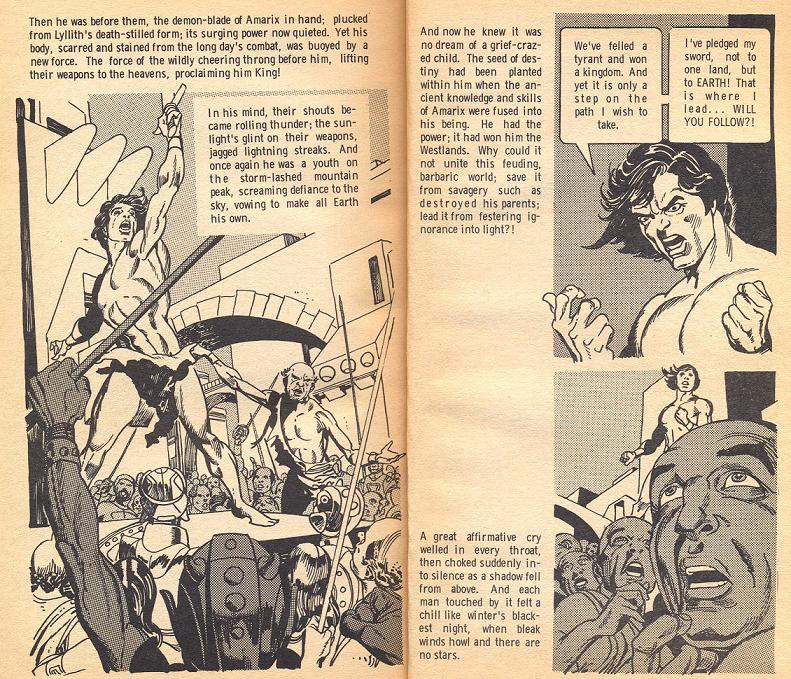

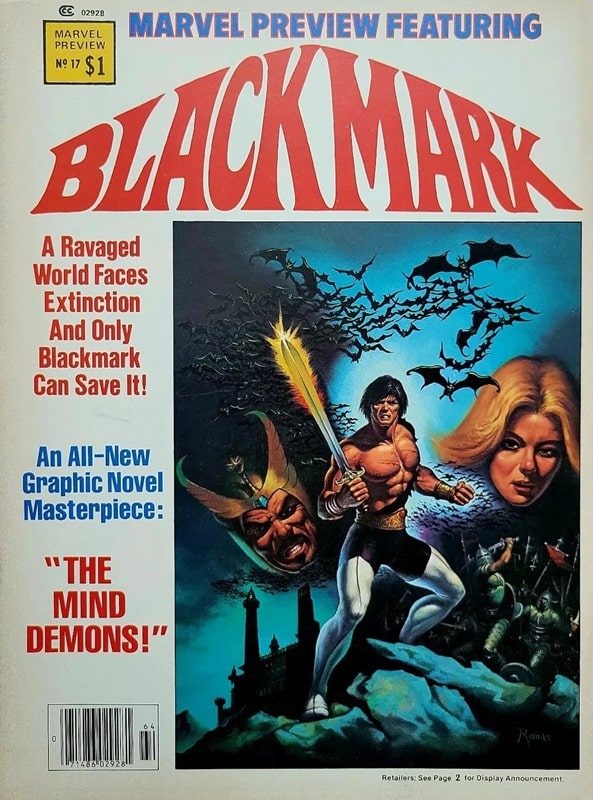

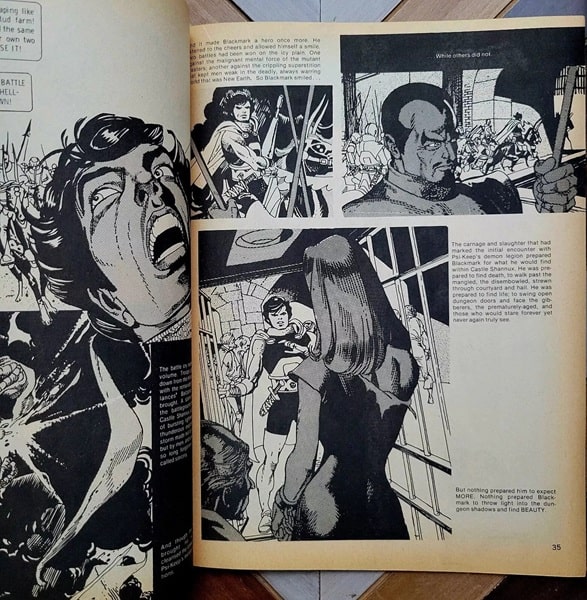

Charles Gramlich administers The Swords & Planet League group on Facebook, where this post first appeared. His last article for Black Gate was Sword & Sorcery on a Post-Apocalyptic Earth: Blackmark by Gil Kane.

Windy City Pulp & Paper 2025 – ‘If Bob Were Here…’

It’s an early A (Black) Gat in the Hand, as I got my Pulp on week before last, at Windy City, in Chicago.

It’s an early A (Black) Gat in the Hand, as I got my Pulp on week before last, at Windy City, in Chicago.

I managed to resist the impulse to grab the microphone in the Dealers Room and proclaim, “Finally….The Bob…has come back…to Windy City.” A little classic Rock for you there. And in not doing so, I wasn’t evicted and had a great time.

Doug Ellis puts on the Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention annually at the Lombard Westin, in the suburb an hour west of Chicago. I last attended in 2019. Of course, COVID hit in 2020, along with some other life changes. I made it to my first Howard Days in 2022, and headed over to Pittsburgh the last two years for Pulp Fest. Windy City just didn’t quite happen. But I made sure it did in 2025.

There’s an auction, some panels, an art show, and a massive Dealer Room. I’ll share my purchases here in a minute. But hands down, the best part of Windy City for me, is hanging and chatting with people. I see lots of online friends and some folks I’ve met before. I even make new friends. Sort of.

Walking around the Dealer Room and getting into conversations on pulp or paperback favorites is a blast. I find somebody to chat Nero Wolfe, or Jo Gar, or Solar Pons, or Solomon Kane, or Bail Bond Dodd, or…you get the idea. I found myself showing my Civil War shelfie to someone, as they talked about Shelby Foote.

There are always folks sitting around the lobby. I’ve met new friends just sitting down and working into the conversation. Saturday night, Ryan Harvey, Chris Hocking, James Enge, and I, spent over two hours just riffing through movies and writers. Ryan’s knowledge of multiple movie genres is staggering. And what those three knew about movie soundtracks left me soaking it in.

Add in eating a couple meals with friends, and the social aspect of Windy City is hands down my favorite part. As you’ll see, I find things to buy – and I restrain myself every year – but it’s talking about mutual interests at Windy City that is the highlight for me. Glad I made it back. See you there in 2026? Between the ever-present LA Dodgers cab, and a shirt with ‘Byrne’s Pub’ writ large on the back, I’m easy to spot.

What Did I Buy?

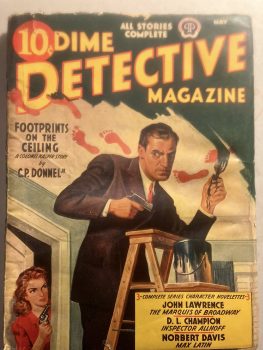

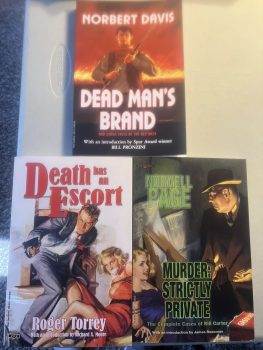

Max Latin!You may (or may not) know, I wrote the introduction to Steeger Books’ reissue of the collected Max Latin short stories. Norbert Davis is on my Hardboiled Mt. Rushmore, and the shady private eye Latin, is my favorite work of his. The fact that my intro replaced the last professional piece written by my favorite writer, John D. MacDonald, is awesome. You can read my intro, here at Black Gate.

For $70, I got the May 1942 issue of Dime Detective, containing “Give the Devil His Due.” This was the fifth Latin story, and I am now the proud owner of an original Latin story. There’s also a Marquis of Broadway by John Lawrence in this issue.

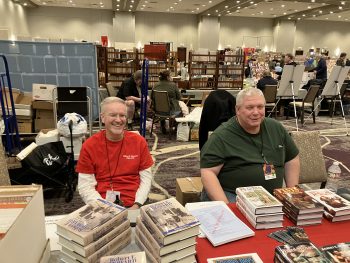

Gotta Have Some Howard! Will Oliver on the left. I think Security was trying to find the guy on the right, most of the show. Wait, that’s John Bullard. I stand by what I said…

Will Oliver on the left. I think Security was trying to find the guy on the right, most of the show. Wait, that’s John Bullard. I stand by what I said…

I resisted the impulse to bring home a haul of Robert E. Howard-related books. It’s easy to find more cool stuff to add to my library – even if I already have the stories included. But Robert E. Howard Foundation folks. Bill Cavalier, Paul Herman, and John Bullard were there. And breakfast with John and Paul was a conversational potpourri I won’t soon forget!

Held every June in REH’s hometown of Cross Plain, TX, Howard Days is a terrific gathering of Howard fans from all over the world. I wish I’d been into Howard back when I lived in Austin. Highly recommended weekend.

I met Will Oliver, a really cool guy (when you’re as cool as I am, you are drawn to other cool people. Yeah…) when I was down there. Will just put out an extensively referenced, door-stopper of a biography of Howard. I grabbed a copy directly from Will at the table, which he kindly signed. I am looking forward to digging into this and probably talking about it during this summer’s run of A (Black) Gat in the Hand.

Cool & LamI’ve written about my favorite Erle Stanley Gardner series many times here at Black Gate. But it’s not Perry Mason. I like the do-it-all lawyer, but the mismatched duo of Bertha Cool and Donald Lam easily hold my ESG top spot. You can find all of my Cool and Lam posts here, including the ‘lost’ pilot, with an intro by Gardner himself.

I don’t have quite all the books, and many are falling apart. As in, I’ve had to toss a couple. Those old Dell paperbacks get extremely brittle. I was happy to pick up two replacement copies at just $5 each. If you haven’t read Cool and Lam, you’re missing out on some high quality PI fiction. At least check out my first post on them, which is based on essay I wrote for Black Mask magazine (yeah, I appeared in THE Black Mask!).

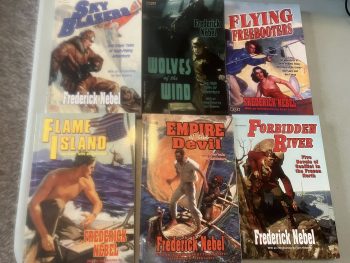

The Frederick Nebel Library Grows So, Norbert Davis’s is the third face on my Hardboiled Mt. Rushmore. Frederick Nebel is number two. Nebel was the guy that Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw tapped to slide into Dashiell Hammett’s place when the latter left Black Mask (and the Pulps). My library has a lot of Nebel from Steeger Books, including Cardigan, MacBride and Kennedy, and the under-appreciated Gales & McGill.

So, Norbert Davis’s is the third face on my Hardboiled Mt. Rushmore. Frederick Nebel is number two. Nebel was the guy that Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw tapped to slide into Dashiell Hammett’s place when the latter left Black Mask (and the Pulps). My library has a lot of Nebel from Steeger Books, including Cardigan, MacBride and Kennedy, and the under-appreciated Gales & McGill.

I already had a couple of Nebel’s air adventures from Illinois’ Black Dog Books. But when I saw Tom Roberts with a table at Windy City, I couldn’t resist. I picked up Sky Blazers, plus the three books along the bottom. Also, three more non-Nebels. I have a couple other digital books from Black Dog. Tom is putting out terrific Pulp by a lot of authors who deserve to still be read. And he has some great intros (I’m still trying to con him… I mean, convince him, to let me write one). I’m a fan of Black Dog, and you should check them out.

Sky Blazers/Wolves of the Wind/Flying Freebooters

I’m not into the Air Pulp genre – in fact, I can’t really even discuss it knowledgeably (like THAT ever stops me, as you well know). But I really enjoy Nebel’s Gales & McGill series, just about all of which appeared in Air Stories, I believe.

I now own all six Nebel books from Black Dog. The top three are all air stories, a few with recurring characters. Nebel and Horace McCoy are the only Air Pulps writers I read, and I’m looking forward to more Nebel.

Flame Island and Empire of the Devil are short story collections of exotic tales from the Adventure Pulps. This is another genre I haven’t read much, but with over 600 pages of Nebel, I’ll be working my way through these. Two of the stories were made into films.

Forbidden River – Nebel started out writing Canadian adventures – you know, Mounties and trappers. Forbidden River contains five such stories. Steeger has also put out two collections of these. Nebel was writing Northern adventures when he joined Black Mask.

Roger TorreyI have the excellent short story collection, Bodyguard, in digital. I couldn’t pass up a second Torrey book: this time in print. Torrey wrote in a straight hardboiled style, and he didn’t change at all as the genre moved more towards the Cornell Woolrich or John D. MacDonald style of mysteries. He was also a major alcoholic and became unreliable and of quite variable quality. He died young, still writing for the ‘lesser’ pulps. But when he was good, he was very good, and I’m a Torrey fan.

Norvell Page Page is best known as the primary writer of the hero Pulp, The Spider (under the house name, Grant Stockbridge). Like most Pulpsters, he wrote many genres, including weird menace, and G-men stories. I have his limited Western output as a Black Dog e-book.

Page is best known as the primary writer of the hero Pulp, The Spider (under the house name, Grant Stockbridge). Like most Pulpsters, he wrote many genres, including weird menace, and G-men stories. I have his limited Western output as a Black Dog e-book.

I really struggle with the Spicy Pulps. Briefly a popular genre, they’re just so goofy I can’t take them seriously enough to enjoy them. I wrote a post on a Robert E. Howard spicy story – and it was more of a saucy-tinged adventure. Whereas, I can’t even finish a Dan Turner (Hollywood Detective) story

in one -sitting.

Robert Leslie Bellem’s Turner is the most popular of the spicy detectives, even getting his own magazine. But to me, it’s like a parody of Race Williams. And Williams can be hard enough to absorb, without making it a spicy parody.

Page wrote a series of spicy stories featuring Bill Carter (who is not his Weird Menace star, Ken Carter), an investigative reporter in Miami. This volume collects (all?) twenty of them. Page is still kinda over-the-top for me, but these are FAR more readable than the Dan Turner stories. I’ll work my way through this book.

Norbert Davis’ WesternsI already had this in digital, but I couldn’t pass up the print edition. Davis didn’t write many Westerns, but he wrote some damn good ones. I already did this Black Gate post on one of my favorites, “A Gunsmoke Case for Major Cain.” I plan on covering a couple more for the summer Pulp series along the way. I really like his Westerns.

MISCI also picked up a Dell Mapback of Rex Stout’s Tecumseh Fox mystery, Double for Death. I like Mapbacks, and try to pick up one or two when they aren’t too expensive. I got a few Stouts last year at Pulp Fest.

Also, you should definitely attend Windy City next year if you want to play ‘If Bob Were Here.’ To hear something I said repeated back conversationally with “If Bob were here, I bet he would say…” I’m used to being ragged on. To combine it with being ignored is really impressive!

The Art Room

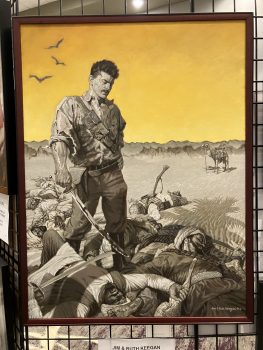

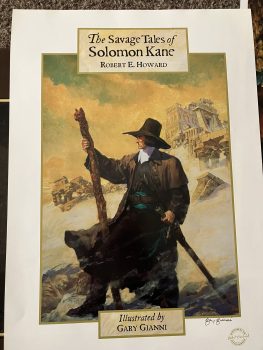

I snapped a few pics of the really cool stuff in the Art Show, but I wish I had been dialed in for it. I would have gotten a lot. The Mark Wheatley, and Gary Gianni stuff, had most of my attention. But there was some neat REH and Edger Rice Burroughs stuff too.

I snapped a few pics of the really cool stuff in the Art Show, but I wish I had been dialed in for it. I would have gotten a lot. The Mark Wheatley, and Gary Gianni stuff, had most of my attention. But there was some neat REH and Edger Rice Burroughs stuff too.

I like this El Borak print by Jim and Ruth Keegan, from the Wandering Star/Del Rey books. There was a cool Solomon Kane pic by Gianni. There was a statue in front of it which it mirrors. I wish I’d taken a close up of it. I will be more focused when I visit the Art Room next time.

Gary Gianni was selling five prints for $30 – signed, at a table. I snagged them! There were four Solomon Kanes – color, and black and white. Also, one larger sized Conan from “A Witch Shall Be Born.”

He chatted with folks and is a super nice guy. I’m friends with Bill Cavalier (well, I don’t think he refutes that statement, anyways) and have met Mark Wheatley and Mark Schulz at Pulp Fest. Robert E. Howard artists have been really nice folks.

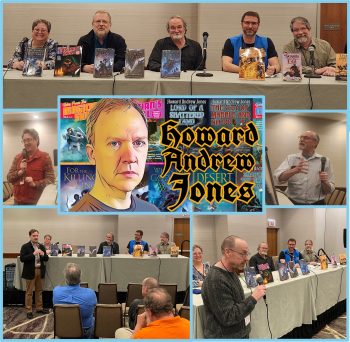

THE HOWARD ANDREW JONES PANEL

A lot of Howard’s friends and fans were at Windy City. There was a panel to remember and celebrate Howard, curated by his biggest fan and supporter, Arin Komins. John O’Neill, James Enge, Seth Lindberg, and John Hocking shared thoughts and memories. Audience members were also offered the opportunity to speak, and Howard’s fellow Black Gaters Ryan Harvey, Greg Mele, and myself, spoke fondly of our missed friend.

A lot of Howard’s friends and fans were at Windy City. There was a panel to remember and celebrate Howard, curated by his biggest fan and supporter, Arin Komins. John O’Neill, James Enge, Seth Lindberg, and John Hocking shared thoughts and memories. Audience members were also offered the opportunity to speak, and Howard’s fellow Black Gaters Ryan Harvey, Greg Mele, and myself, spoke fondly of our missed friend.

Kudos to Doug Ellis for setting aside time for Howard to be front and center. Mentions of him were peppered throughout the weekend among the Black Gate and associated crowd. We will be fondly remembering him for a long time to come.

One audience member came up and talked about helping when Howard was putting together the Harold Lamb collections. And he revealed there were some Lamb stories (four, maybe?) that they didn’t have the rights to, and I think Howard had edited those as well. Would be need to see those added to Howard’s Lamb work.

Jason Waltz – you can believe I took Arin and company to task as they were setting up the books, and there was no Hither Came Conan!

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand

2025 (1)

2024 Series (11)

Will Murray on Dashiell Hammett’s Elusive Glass Key

Ya Gotta Ask – Reprise

Rex Stout’s “The Mother of Invention”

Dime Detective, August, 1941

John D. MacDonald’s “Ring Around the Readhead”

Harboiled Manila – Raoul Whitfield’s Jo Gar

7 Upcoming A (Black) Gat in the Hand Attractions

Paul Cain’s Fast One (my intro)

Dashiell Hammett – The Girl with the Silver Eyes (my intro)

Richard Demming’s Manville Moon

More Thrilling Adventures from REH

Prior Posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2023 Series (15)

Back Down those Mean Streets in 2023

Will Murray on Hammett Didn’t Write “The Diamond Wager”

Dashiell Hammett – ZigZags of Treachery (my intro)

Ten Pulp Things I Think I Think

Evan Lewis on Cleve Adams

T,T, Flynn’s Mike & Trixie (The ‘Lost Intro’)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part I (Breckenridge Elkins)

John Bullard on REH’s Rough and Ready Clowns of the West – Part II

William Patrick Murray on Supernatural Westerns, and Crossing Genres

Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘Getting Away With Murder (And ‘A Black (Gat)’ turns 100!)

James Reasoner on Robert E. Howard’s Trail Towns of the old West

Frank Schildiner on Solomon Kane

Paul Bishop on The Fists of Robert E. Howard

John Lawrence’s Cass Blue

Dave Hardy on REH’s El Borak

Dave Hardy on REH’s El Borak

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2022 Series (16)

Asimov – Sci Fi Meets the Police Procedural

The Adventures of Christopher London

Weird Menace from Robert E. Howard

Spicy Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Thrilling Adventures from Robert E. Howard

Norbert Davis’ “The Gin Monkey”

Tracer Bullet

Shovel’s Painful Predicament

Back Porch Pulp #1

Wally Conger on ‘The Hollywood Troubleshooter Saga’

Arsenic and Old Lace

David Dodge

Glen Cook’s Garrett, PI

John Leslie’s Key West Private Eye

Back Porch Pulp #2

Norbert Davis’ Max Latin

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2021 Series (7 )

The Forgotten Black Masker – Norbert Davis

Appaloosa

A (Black) Gat in the Hand is Back!

Black Mask – March, 1932

Three Gun Terry Mack & Carroll John Daly

Bounty Hunters & Bail Bondsmen

Norbert Davis in Black Mask – Volume 1

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2020 Series (21)

Hardboiled May on TCM

Some Hardboiled streaming options

Johnny O’Clock (Dick Powell)

Hardboiled June on TCM

Bullets or Ballots (Humphrey Bogart)

Phililp Marlowe – Private Eye (Powers Boothe)

Cool and Lam

All Through the Night (Bogart)

Dick Powell as Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar

Hardboiled July on TCM

YTJD – The Emily Braddock Matter (John Lund)

Richard Diamond – The Betty Moran Case (Dick Powell)

Bold Venture (Bogart & Bacall)

Hardboiled August on TCM

Norbert Davis – ‘Have one on the House’

with Steven H Silver: C.M. Kornbluth’s Pulp

Norbert Davis – ‘Don’t You Cry for Me’

Talking About Philip Marlowe

Steven H Silver Asks you to Name This Movie

Cajun Hardboiled – Dave Robicheaux

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

More Cool & Lam from Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series (15)

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

Will Murray on Doc Savage

Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman

A Man Called Spade

Hard Boiled Holmes

Duane Spurlock on T.T. Flynn

Andrew Salmon on Montreal Noir

Frank Schildiner on The Bad Guys of Pulp

Steve Scott on John D. MacDonald’s ‘Park Falkner’

William Patrick Murray on The Spider

John D. MacDonald & Mickey Spillane

Norbert Davis goes West(ern)

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

Bill Crider on The Brass Cupcake

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series (32)

George Harmon Coxe

Raoul Whitfield

Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

Thomas Walsh

Black Mask – January, 1935

Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

Dime Detective – August, 1939

Back Deck Pulp #1

W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Phantom Crook (Ed Jenkins)

Day Keene

Black Mask – October, 1933

Back Deck Pulp #2

Black Mask – Spring, 2017

Erle Stanley Gardner’s ‘The Shrieking Skeleton’

Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

Back Deck Pulp #3

Back Deck Pulp #4

Back Deck Pulp #5

Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

Back Deck Pulp #6

The Black Mask Dinner

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXIII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

You can definitely ‘experience the Bobness’ at Jason Waltz’s ’24? in 42′ podcast.

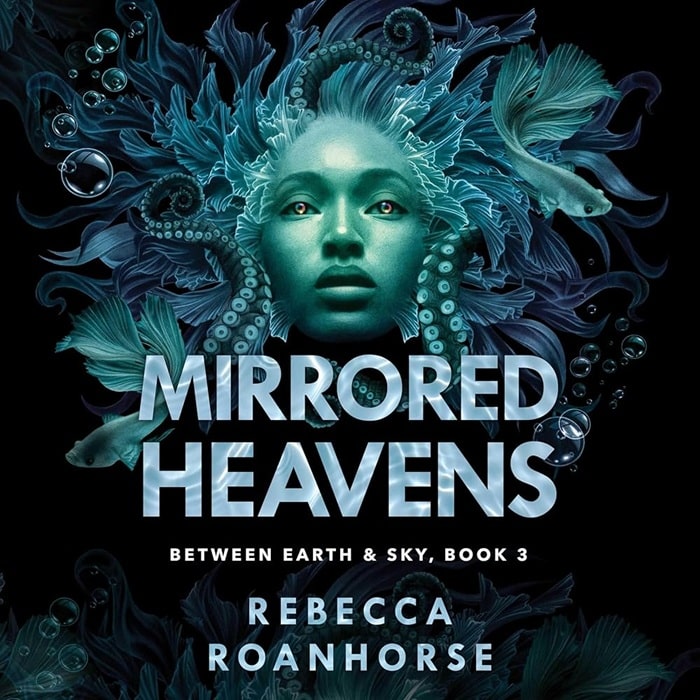

Neverwhens: War “On Earth, As it Is in Heaven” — Rebecca Roanhorse’s Mirrored Heavens

Mirrored Heavens by Rebecca Roanhorse (Saga Press, June 4, 2024)

Mirrored Heavens by Rebecca Roanhorse (Saga Press, June 4, 2024)

Between Earth & Sky has always been about doing something fresh.

Rebecca Roanhorse set out to create an epic fantasy set in a world based on the pre-contact Americas. It has its Maya, Cahokia, Ancestral Puebloan and Woodlands analog cultures; it has a seafaring matriarchy that is a bit Polynesian, a bit Caribbean, a bit “this would be cool.” But the world of The Meridian is its own thing. At times the technology is greater than what existed in our world, it has giant crows, eagles, insects and winged serpents tamed as mounts and its gods are very real, and not particularly benevolent.

But if the world the author sets her fantasy is drawing from cultures underused in fantasy, the story-structure is unique as well. This is not a story of a rising dark lord and the plucky heroes that rise against him. Its villains are all-too-human, motivate by sometimes petty desires, sometimes misplaced love, and if there is a “Dark Lord”, well he is one of the most sympathetic characters in the entire tale.

None of this is inversion for inversion’s sake; it is about telling a compelling, fresh story that feels authentic to the sources that inspired its author, and now it has all come to an end with Mirrored Heavens.

Sticking a landing is always tricky and Roanhorse to some extent set herself a challenging task at the end of Book 2. The mid-book of a trilogy is always a bridge story of revelations and few resolutions, but in Fevered Star we only truly see into the villain’s mind — or even realize his full roll — in the last third of the book. Our two main pairs of heroes: Serapio and Xiala, Narampa and Ixtan, spend the novel separated while the fifth main hero, Okoa, is mostly haplessly dragged from bad decision to bad decision. Things end with the predictable “it’s even worse now”, but other than an epic, beautifully rendered clash between Serapio and Narampa, as respective avatars of the Crow and Sun, in some ways the stage feels unset for resolution in one volume.

That would all be true if Roanhorse was trying to write The Lords of the Rings, pre-Contact Americas style. But she isn’t, and her story isn’t triggered by plot, but by characters. If there is a reveal in Fevered Star it is that all of our main characters, even the villainous Balam, have been motivated by personal relationships, disappointments or love. For all the interplay of ancient gods and prophecies, the story is indeed about Serapio and Xiala, Narampa and Ixtan, Okoa and yes, even evil Balam. It’s about family and isolation, a desire to belong and be loved, or what happens when that instead turns into possessive control. Consequently, to borrow a line from the otherwise wretched The Last Jedi: This isn’t going to go how you think it will.

Reading the above, one might think this is a very literary, slow book. It is not. From the first page there is assassination attempts, blood magic, scary monsters and marching armies. As with the first two volumes, Roanhorse’s prose is tight, sometimes even clipped, and her pages fly by. The summary of our situation: Serapio, now the Carrion King and ruler of Tova, is trying to cement his rule as the Crow clan’s living messiah, and knows that besides the other clans wishing to murder him, the rulership of his own clan has no love for being supplanted by living avatar.

All the other cities of the confederacy are marshalling against him, and he doesn’t even know that the villain behind it all is the man who sent him on his quest — and has been involved in his very creation from the start. He is presented with a prophecy, supposedly from the maw of the trickster god Coyote himself that says that if he slays his “unloved bride” and his father, he can win the three different wars brewing against him, but only by losing everything. What the hell does that mean, and how much further into dark, even cruel, paths will Serapio descend to fulfill it. Indeed — is he even the “good guy” and what is he trying to win?

Okoa, as brother to the Carrion Crow matron, has come to respect and idolize Serapio, but like everyone — fears him. His sister reveals the other clan matrons have learned of a weapon that can slay the Carrion King and demands Okoa’s help.

Narampa feels the power of the Sun growing in her and has fled to the north, to the Graveyard of the Gods — where it is said the gods made war and were “slain”/banished from the mortal world — seeking a shaman who can teach her how to use the mysterious godflesh mushrooms that will allow her to enter the various spirit worlds and fight to liberate her city from the Crow. Only she, too, does not realize Serapio is not the problem…

Ixtan is in the city of Hokaia, adrift and unsure what their path now is, until they learn that Narampa lives and that the southern lord Balam is at the heart of everything. A dangerous thing for a “Priest of Knives” to learn.

Xiala has returned home to the isles of the reclusive Teek. Her mother dead, she should be queen — a role she has run from. But Lord Balam’s agents have come to enslave the Teek, and somehow she has to save her people and find a way back to Serapio to warn him.

Seem like spoilers? That’s where we pick up and in a way that’s all you need to know. The rest of Mirrored Heavens is about how each of these players follows that path, and a revelation of how Lord Balam came to be bent on quest of the cities of the Meridian. The resolution will have blood magic, shadow worlds, a clash between gods, love and definite loss…and it won’t be what you think.

Now, confession: I came close to rating this to four stars because, with so much to resolve and tie up, it is only within the last 70 pages of a 600-page novel that it all starts to come into motion. The final clash is certainly dramatic, maybe almost too much — it feels very much like the final confrontation scene would expect in a Marvel movie, or at least an 80s adventure film. For all of the build-up, Serapio and Narampa are not fated to meet again and, indeed, many characters here fail to understand their role in the story, or make choices that lead to worse, not better, and never do recover from it.

A key to victory comes from an idea introduced about five pages before it is used, which felt contrived. Finally, the more we learn of Lord Balam’s backstory, the less competent he seems, and more like the real-world’s over-privileged billionaires who are interfering in the modern world simply because they can, they have the resources to bully their way in, and because they don’t like being told no. It all felt a bit rushed, and not always fair to the characters we’d been running with for 1600 pages.

Then I read the two final chapters, that serve as epilogues.

As I said at the start of this review, Rebecca Roanhorse isn’t trying to write a “Native American Lord of the Rings“, she is telling her own tale, and when you get to the end it all clicks. Besides tying every loose end, the other choices: a somewhat tragic, almost pointless, death of a main character; the fact that an assassin not only gets away with it, but parleys their actions into more power; the fact that some of the great heroism of a character is never known or understood — yes, that’s how the world works in politics and in war.

The gods are real, yet their ultimate appearance remains vague, unclear, and seemingly uncaring of mortal cost because they are gods — not mortals writ large. There is nothing of the Classical or Judeo-Christian belief to these deities; they are primal and simply are — once they act, mortals are left to reason for themselves what it all means. Scenes that occur off-stage do so because they really tell us nothing about the interplay of the core characters, and that’s what this story has always been about: a small group of players caught in the center of a revenge decades in the making.

Could the end have been a bit longer? Perhaps. Do I still think Lord Balam never really quite works as the chief villain? Somewhat. Is the “secret weapon” introduced just before it is needed… needed. No. But in the end, that doesn’t matter: Mirrored Heavens is ultimately about people and in telling that story, Roanhorse creates a magic and adventure-filled conclusion to one of the freshest epic fantasies I’ve read in years. I am already missing Serapio, Xiala, Ixtan and the rest, and although the story of The Meridian seems complete, Roanhorse mentions a distant western Empire of the Boundless Seas and other lands I’d eagerly visit.

(You can read my review of volume one here: Neverwhens, Where History and Fantasy Collide: Brilliance Gleams Beneath a Black Sun.)

Tubi Dive, Part I

How to Make a Monster ( American International Pictures, July 1, 1958)

How to Make a Monster ( American International Pictures, July 1, 1958)

50 films that I dug up on Tubi.

Enjoy!

How to Make a Monster – 1958, AIPAs a slight deviation from our usual programming of themed lists, here are the results of a deep dive I recently undertook, pushing Tubi to the limits. So here we are with How to make a Monster, a follow-up of sorts to the two spectacular schlock movies, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein and I Was a Teenage Werewolf, both released a year earlier in 1957 from American International Pictures. Monster double-billed with Teenage Caveman (which I previously reviewed when I was on my cave people kick), and is probably my favorite of the film series.

It isn’t your usual narrative, but rather a meta-tale of the studio itself, and I LOVE movies about making movies. In this one, Pete Dumond, the ‘Jack Pierce’ of his day, is the makeup wizard who designed and applied the prosthetics for the two previous films. When he discovers that the studio has been taken over by a company that isn’t interested in monster films, and is subsequently fired, Pete goes on a murderous rampage, only he doesn’t do the killing himself. Instead he brainwashes the young actors playing the monsters via a strange foundation cream (bear with me here) and coerces them to killing the new studio stooges while in full makeup.

Eventually, the cops figure out what is going on, and it all ends up in a rather bonkers and fiery final act. One of the great gimmicks employed here is the final reel being in full colour (a similar stunt was pulled on Teenage Frankenstein), and it’s quite jarring, but in a good way. Fun stuff!

7/10

Craze (Warner Bros, June 5, 1974)

Craze (1974)

Craze (Warner Bros, June 5, 1974)

Craze (1974)

A strange little film from one of my favorite directors, Freddie Francis (who hated this one), Craze is based on the novel The Infernal Idol by Henry Seymour. It tells the story of an English antiques dealer who is wrapped up in black magic, and who worships a spooky African idol called Chuku. After a bloody alter, he begins to associate human sacrifices with financial gain (via Chuku), and promptly goes on a murderous spree to keep his idol happy.

Jack Palance is the most unconvincing Englishman ever put on film (until Keanu in Dracula), but he is ably supported by Julie Ege, Diana Dors and Trevor Howard. There are moments that echo the Amicus glory days, however it’s an uneven film, and the version I watched appeared to be edited for ghastliness.

Good if you’re planning a scary idol night.

5/10

The Fifth Floor (Film Ventures International, November 15, 1978)

and The Boneyard (Zia Film Distribution, June 12, 1991)

Based on a true story, The Fifth Floor is about a young woman, Kelly (played by Diane Hull), who is accidentally poisoned at a disco and is taken to hospital. Her records indicate that she has tried to self harm before at age 15, so she is recommended for psychiatric assessment and care, leading to a three day stay at a facility. She soon runs afoul of a sleazy attendant, and her stay is increased to two-weeks, eventually being drawn out to 60 days. During this time she is abused, both mentally and sexually, and nobody believes her, especially her useless boyfriend.

It’s a pretty run of the mill movie, but the cast is the standout, and makes this an interesting watch. As with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the patients are portrayed by some familiar faces, notably Robert Englund (fresh off telling his roommate to try auditioning for a space movie…), Anthony James (the villain in every TV show and film you ever watched), Earl Boen (who would go on to become a psychiatrist himself in the Terminator films), and Michael Berryman (of course).

The uncaring boss of the facility is played by Mel Ferrer, and the sleazy, abusive orderly is played by none other than Bo Hopkins. Julie Adams plays one of the nurses, so of course this Black Lagoon lover was very happy about that.

Not fun, but I didn’t hate it, which is high praise considering the films I seek out.

5/10

The Boneyard (1991)Here’s an interesting one I hadn’t seen before, and when I say interesting, I mean a bit dull, then utterly barking mad.

Two years before The X-Files gave us Mulder and Scully, The Boneyard gave us Jersey Callum (Ed Nelson) and Alley Oates (Deborah Rose), a detective and psychic respectively, both at the end of their games and leaning against each other for support. A child murder case leads them both to a vast mortuary, run by Phyllis Diller (who totally over-Dillers every scene she’s in). Before you know it the child corpses turn out to be flesh-eating demons, and shenanigans ensue.

Yes, this one is painfully slow to get started, but once it does, it’s a lot of fun. The child demons are quite ghastly and really well made, and it’s a pity the same cannot be said for the two goofy monsters that crop up toward the end. James Cummings was a bit of a makeup legend before he tried his hand at directing, and it showed in the monsters — unfortunately the rest of his direction was really pedestrian.

There are some hilarious moments, some gooey moments, and a poodle moment that would make Ang Lee go off in his pants. Worth a look if you’re feeling brave.

6/10

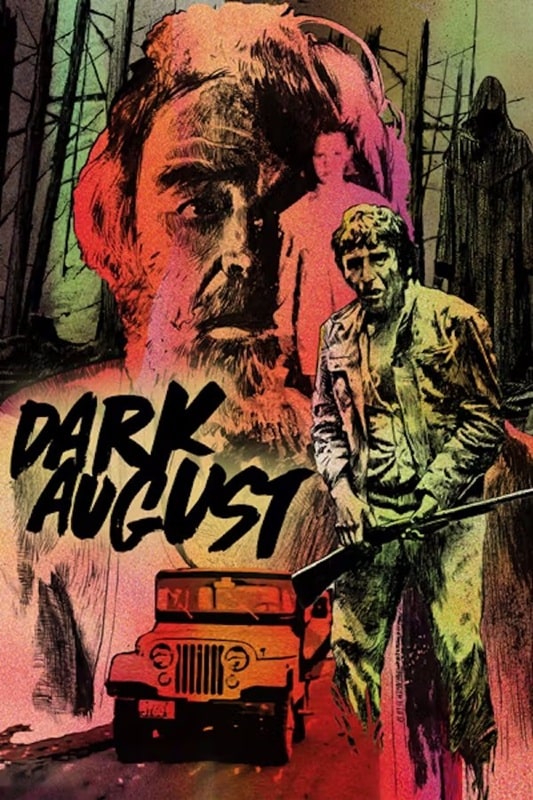

Schizoid (The Cannon Group, September 5, 1980)

and Dark August (Howard Mahler Films, September 10, 1976)

Next up is this non-politically correctly titled slasher from the start of the best decade. Someone is stalking and murdering the members of a therapy group run by the terminally horny Dr. Fales (Kinski).

A newspaper columnist (Marianna Hill) is being sent threatening letters, and the cops (led by Richard Herd) don’t take them seriously. Her creepy ex-husband (Craig Wasson) is more concerned with getting the wallpaper up in his office (!), and Kinski shags everyone.

It’s fine, I guess, except the mystery killer is given away at the beginning. Oh, and Christopher Lloyd is in it, being all weird and sinister, so a bonus point there.

1/10

Dark August (1976)Sal, an artist recently moved from NY to Vermont, doesn’t do a good job of fitting into his new rural life because he immediately runs over a young girl. It’s an accident, but the girl’s spooky grandfather doesn’t see it that way, and proceeds to voodoo Sal up the wazoo.

Creepy apparitions, bloody coughing and tummy aches ensue. It’s a bit slow, but there is a handful of inspired shots. Kim Hunter is in it as a committed medium, so that’s a bonus.

1/10

Baskin ()

Baskin (2015, Turkey)

Baskin ()

Baskin (2015, Turkey)

Just five months after the US Thanksgiving celebrations, here is a delicious slice of Turkey, all wrapped up in one hell of a mind-bending horror film.

Baskin is a simple tale about a squad of police officers just mooching about, not doing much, when they get a call to a ‘disturbance’ in a dodgy part of town.

They answer the call, but crash their van along the way and end up at a big old house. The minute they go inside they are confronted by assorted ghastliness, and another officer banging his own head against a wall, and then it all goes rapidly downhill.

They find themselves quite literally in Hell surrounded by writhing masses of flesh and blood, and soon they are in the clutches of a cannibalistic cult, led by an enigmatic and terrifying figure. The sense of dread is astounding, and the film itself is gorgeous, albeit utterly horrific. Its surreal sensibilities put me in mind of Mandy (2018), and its overall sense of doom reminded me of Descent or Dog Soldiers. It’s a bit of a hard watch, and certainly not fun, but it’s worth a watch if you fancy something darker (and stickier) than molasses.

8/10

Previous Murkey Movie surveys from Neil Baker include:

What Possessed You?

Fan of the Cave Bear

There, Wolves

What a Croc

Prehistrionics

Jumping the Shark

Alien Overlords

Biggus Footus

I Like Big Bugs and I Cannot Lie

The Weird, Weird West

Warrior Women Watch-a-thon

Neil Baker’s last article for us was Part III of What Possessed You? Neil spends his days watching dodgy movies, most of them terrible, in the hope that you might be inspired to watch them too. He is often asked why he doesn’t watch ‘proper’ films, and he honestly doesn’t have a good answer. He is an author, illustrator, teacher, and sculptor of turtle exhibits. (AprilMoonBooks.com).

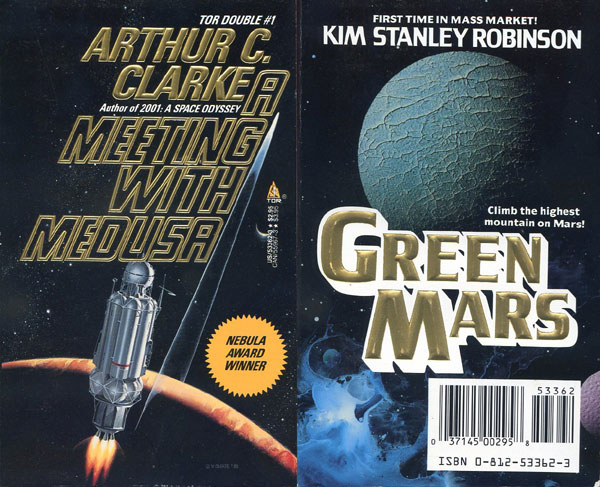

Tor Doubles #1: Arthur C. Clarke’s Meeting with Medusa and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Green Mars

Meeting with Medusa cover by Vincent di Fate

Meeting with Medusa cover by Vincent di FateGreen Mars cover by Vincent di Fate

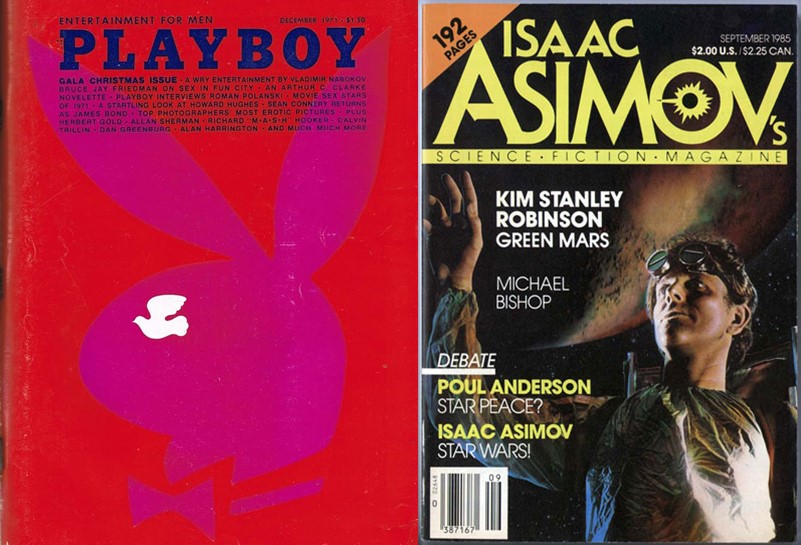

Tor Double #1 was originally published in October 1988. This volume marked the beginning of the official Tor Double series. The two stories included, Arthur C. Clarke’s Meeting with Medusa and Kim Stanley Robinson’s novella Green Mars complement each other, although by doing so, Green Mars also points out a weakness of Meeting with Medusa. The volume was published as a tête-bêche, with both covers were painted by Vincent di Fate.

Meeting with Medusa was originally published in Playboy in December, 1971. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and Nebula Award, winning the latter, as well as the Seiun Award.

The novella opens with Captain Howard Falcon commanding a massive airship, the Queen Elizabeth IV, over the Grand Canyon. A collision with a drone camera causes the ship to crash, killing nearly everyone on-board, including the uplifted chimpanzees who served as part of their crew. Although horribly injured in the crash, Falcon survived and spends years regaining his ability to function, eventually returning to his job as a pilot with an audacious plan.

Falcon proposed a mission to fly through Jupiter’s atmosphere. He notes that many probes have been lost in the atmosphere, but believes that he is uniquely qualified for a crewed mission because he can take evasive action if necessary, noting that he was not at the helm when the Queen Elizabeth IV was struck. His proposal seems like a mix of hubris and a need to atone for the loss of the airship. While Falcon’s reasoning may make sense, the decision to fund and permit him to take on the mission seems a little too pat. However, characterization and motivation has never been Clarke’s forte.

Where Clarke excels, and where Meeting with Medusa succeeds, is building a sense of wonder for the reader. Extrapolating from what was known about Jupiter in the years prior to the first flyby, by Pioneer 10 in 1973, Clarke creates an alien world high in the Jovian atmosphere. Buffeted by hurricane force winds, Falcon provides testimony of the miracles of life that are able to exist there, from the enormous and buoyant medusa, named for the tentacles that dangled beneath them, to the ray-like predators that glide through the skies. The size of these creatures, and the requirements for living where they do, mean that Clarke has incorporated aspects of biology that only exist on a small scale on Earth, if at all.

Gardner Dozois commented that Meeting with Medusa “is a bit traveloguish,” but there is more to the story than simply Falcon’s sightseeing through Jupiter’s skies and achieving a sense of closure for the Queen Elizabeth incident. Clarke provides a more specific reason why Falcon may be the right person for the job, but that final revelation feels a little tacked on and Clarke didn’t make full use of it throughout the story.

Forty-five years after its original publication, authors Stephen Baxter, who collaborated with Clarke, and Alastair Reynolds published a sequel to Meeting with Medusa, the novel The Medusa Chronicles, which expanded on the world Clarke described and the character who explored that world.

Playboy cover by an unknown artist

Playboy cover by an unknown artistAsimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, September 1985, cover by J.K. Potter

The novella Green Mars was originally published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in September, 1985 and should not be confused with Robinson’s 1993 novel Green Mars. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award.

Roger Clayborne, who is around 300 years old, has resigned from his position as Minister of the Interior for Mars, a position he has held for 27 years. A member of the Red Party, which championed the maintenance of Mars in its natural state, he has come to realize that his ideology has lost out to the Greens, who have successfully terraformed Mars to an extent that conserving its pristine nature is no longer possible.

In his own attempt to get back to nature, Clayborne signs on with an expedition to climb Olympus Mons, at 22 kilometers, the tallest mountain in the solar system, with a peak that juts out of the planet’s atmosphere. All expert climbers, including a woman Clayborne knew more than 250 years earlier, the trek up the mountain proves dangerous, between the threat of rockfall, weather, and the thinner Martian atmosphere.

Set over the span of several weeks, Clayborne interacts with nearly all of the other members of the expedition in various ways and the expedition leader, Eileen Monday, makes sure to rotate who partners with whom. With a cast of eleven characters, some do get short shrift (only one of the four “Sherpas” is given a last name and none of them are fleshed out), but Robinson does limn out distinctions between most of the characters, from Marie Whillans’ exuberance to Dougal Burke’s quiet competence. Roger’s interactions often depict part of the story, but Robinson makes clear that there are complex relationships behind the scenes.

Robinson also describes the climb in details, introducing the reader to a variety of concepts used to scale mountains and showing that, even with the relatively gentle slope of Olympus Mons, the ascent is difficult, with a lot of climbing and descending as paths and dead ends are discovered and materials are carefully positioned to ensure the expedition’s chance of success. At the same time, injuries happen and must be dealt with, not always in the most obvious ways.

As Clayborne climbs the mountain, the natural beauty and his discussions with the other climbers slowly begins to make him reconsider what it means to be a Red in a world in which terraforming has already taken hold. By the time he reaches the summit, he comes to a conclusion that he can still work to preserve Mars under what he considers to be less than ideal circumstances, but also understands that a terraformed Mars as a beauty all its own.