https://www.blackgate.com/

Where Dreams and Nightmares Come True: Greyhawk Adventures: Saga of Old City by Gary Gygax

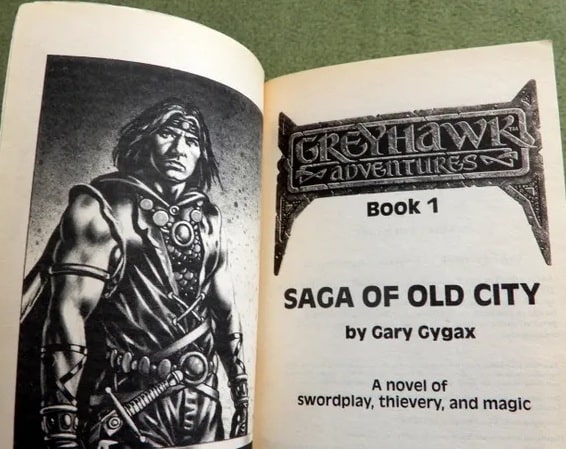

Greyhawk Adventures: Saga of Old City (TSR, October 1985)

Greyhawk…

A cruel city.

A harsh, pitiless city for a young orphan boy with no money and no friends — but plenty of enemies!

Enter the Old City of Greyhawk, that marvelous place where dreams — and nightmares — come true. Travel through the world of Oerth along with Gord, the boy who becomes a man as he fights for his survival in a world of mysterious wizards, fearsome monsters, dour dwarves, and beautiful women.

[Click the images for Greyhawk-sized versions.]

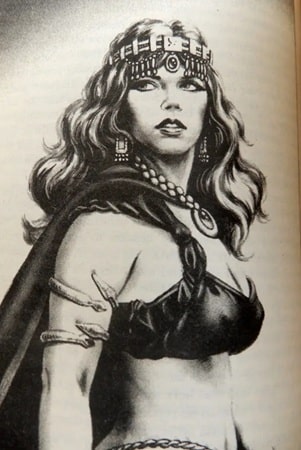

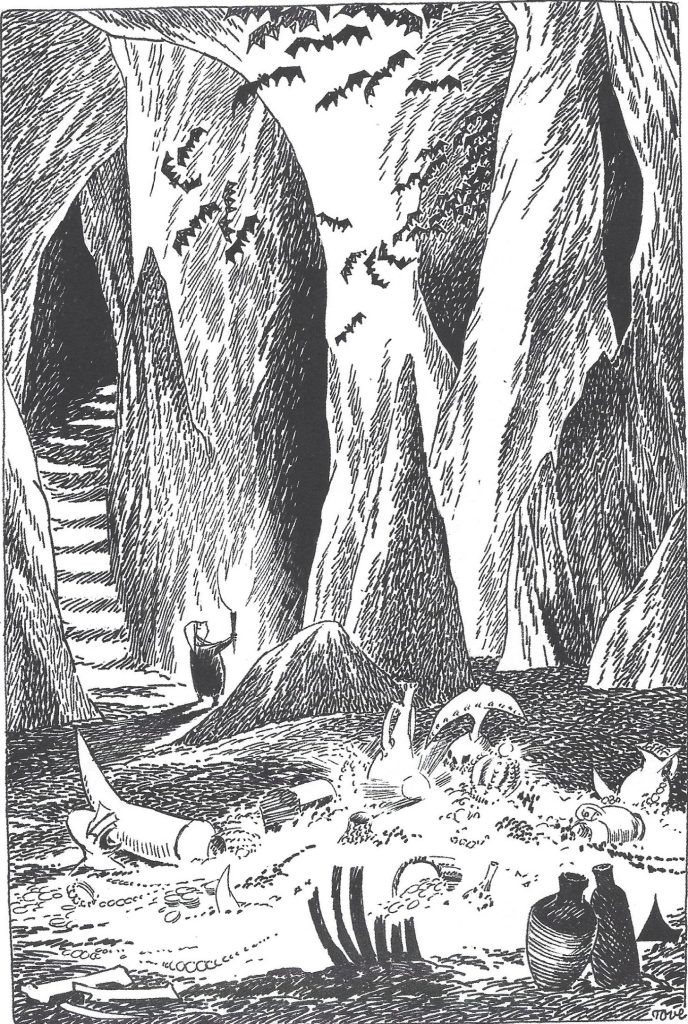

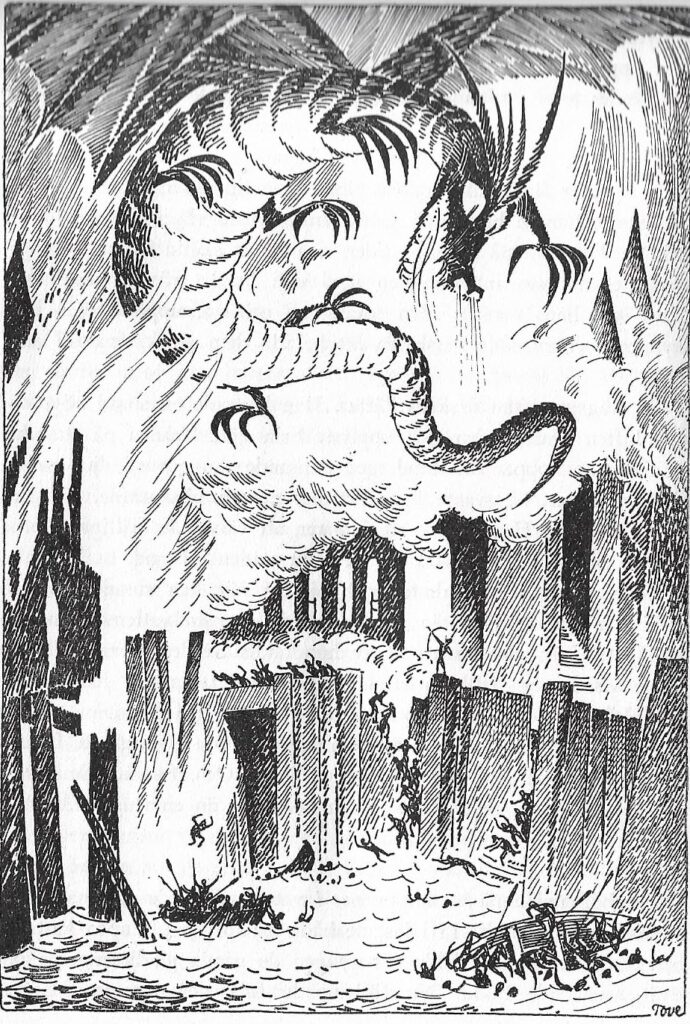

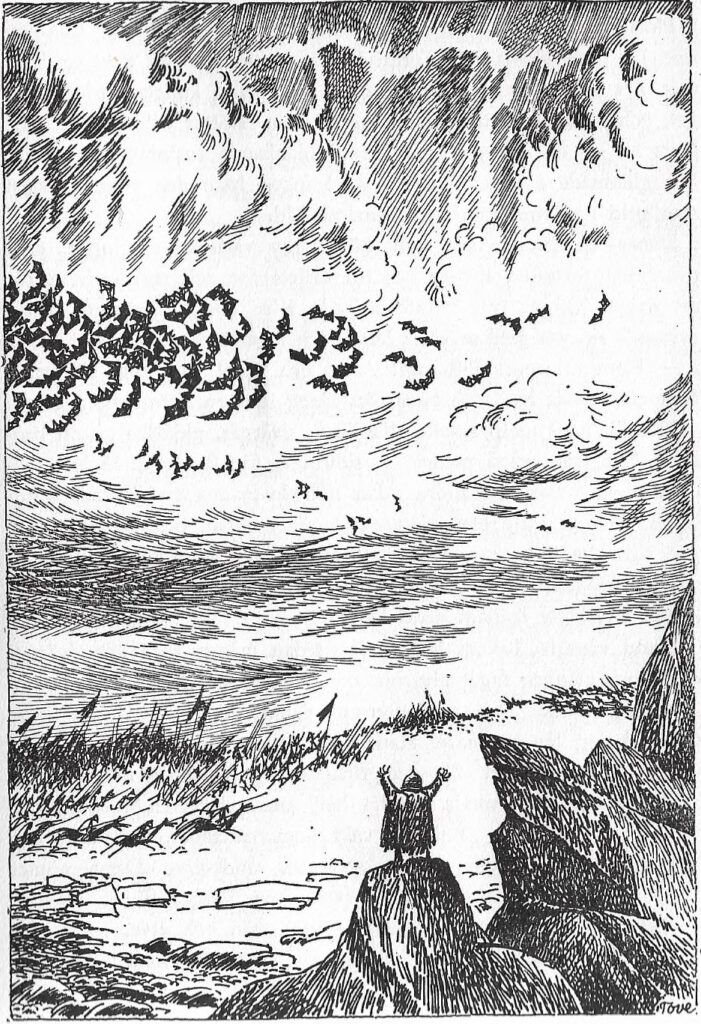

Interior art for Saga of Old City by Clyde Caldwell

For Oerth is a world where a man’s eyes always watch the shadows… and a man’s hand is always on the hilt of his dagger.

Here, at last, is adventure enough to last a lifetime — perhaps a very short lifetime!

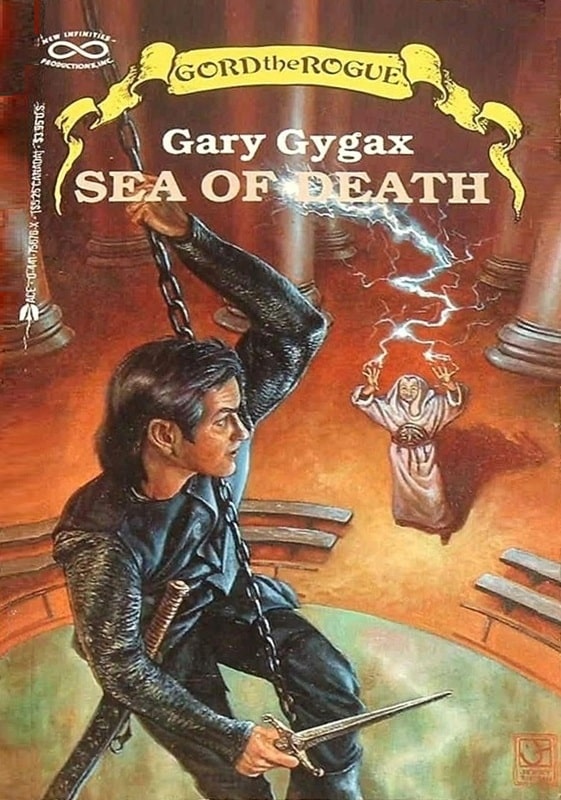

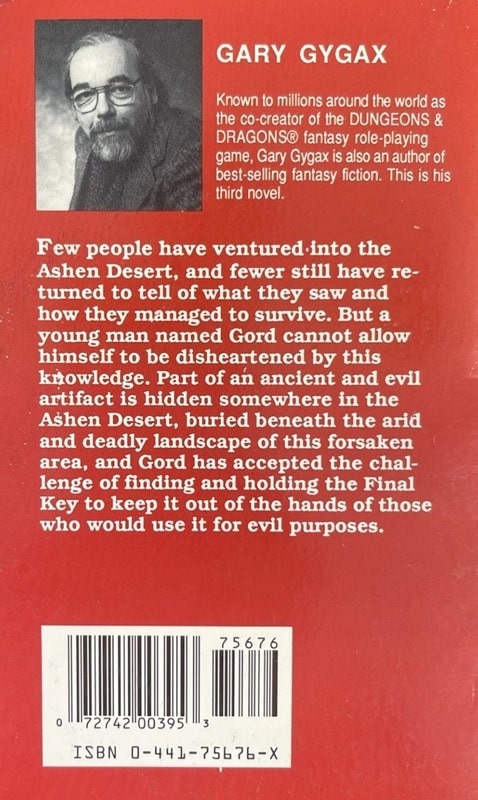

Gord the Rogue #1: Sea of Death (New Infinities Productions, June 1987). Cover by Jerry Tiritilli

Such fond memories of the Gord the Rogue series, by the incredible Gary Gygax. I think my favorite was Sea of Death. Gary was definitely inspired by his pal, Fritz Lieber, as Gord the Rogue was a lot like The Gray Mouser.

Jeffrey P. Talanian’s last article for Black Gate was a look at the Dragonslayer RPG by Greg Gillespie. Jeffrey is the creator and publisher of the Hyperborea sword-and-sorcery and weird science-fantasy RPG from North Wind Adventures. He was the co-author, with E. Gary Gygax, of the Castle Zagyg releases, including several Yggsburgh city supplements, Castle Zagyg: The East Mark Gazetteer, and Castle Zagyg: The Upper Works. Read Gabe Gybing’s interview with Jeffrey here, and follow his latest projects on Facebook and at www.hyperborea.tv.

You Can’t Handle the Tooth, Part III

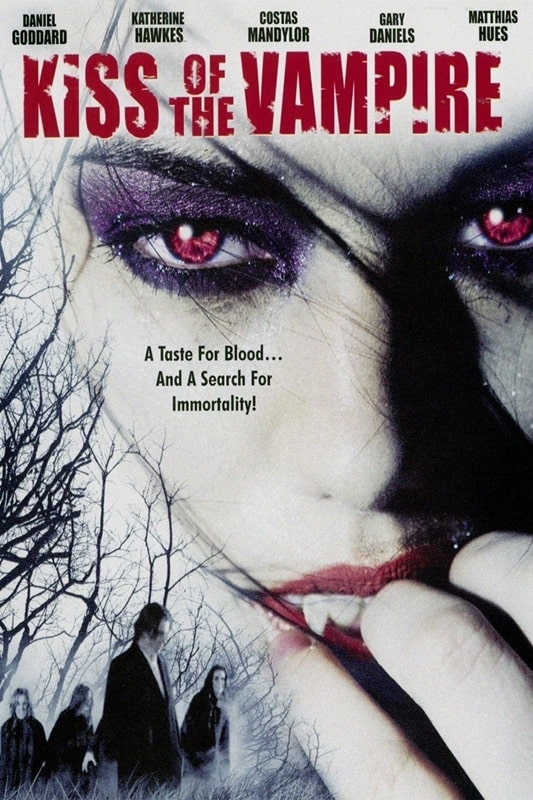

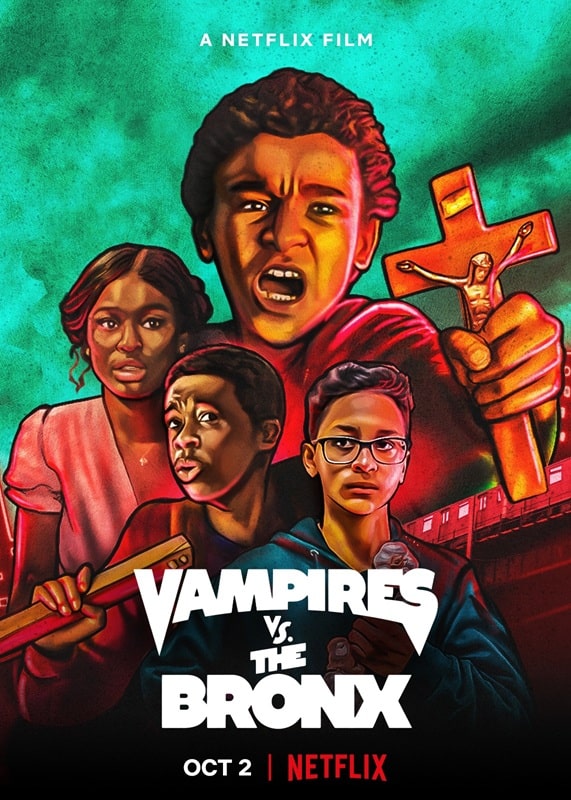

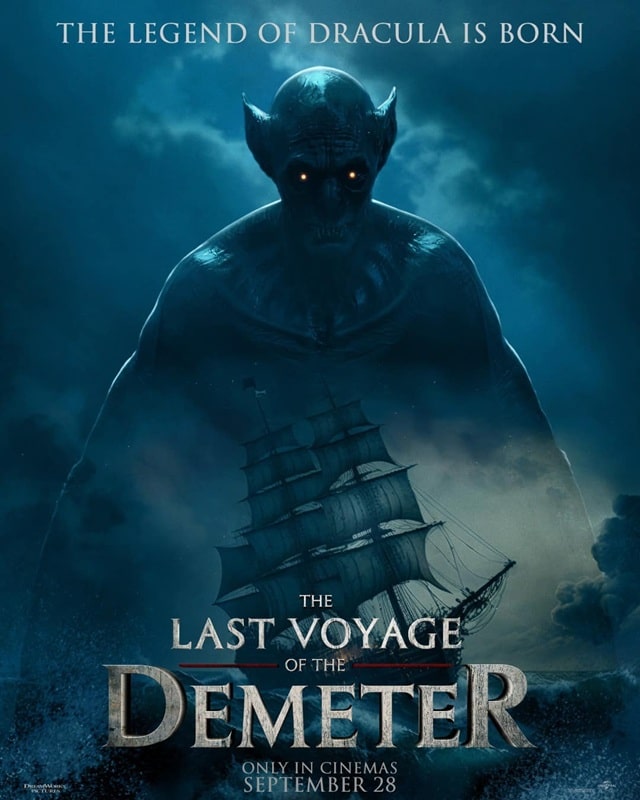

Boys from County Hell (Six Mile High Productions, April 2020)

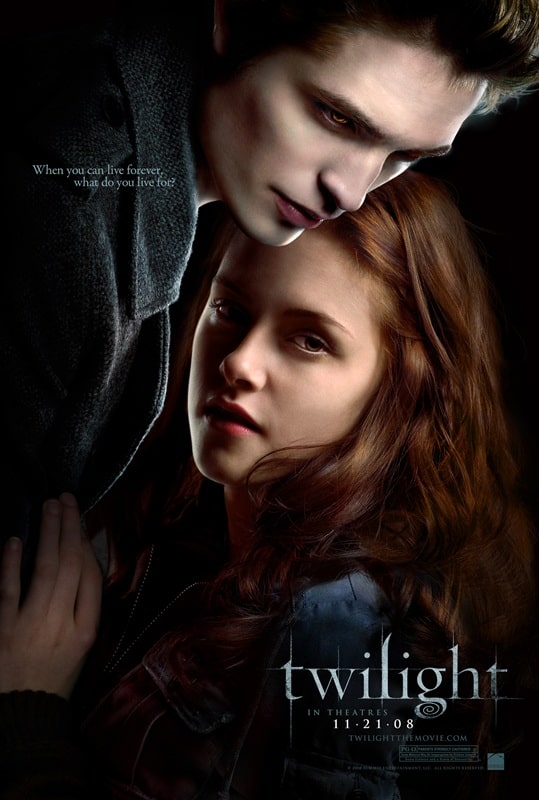

and Twilight (Summit Entertainment, November 21, 2008)

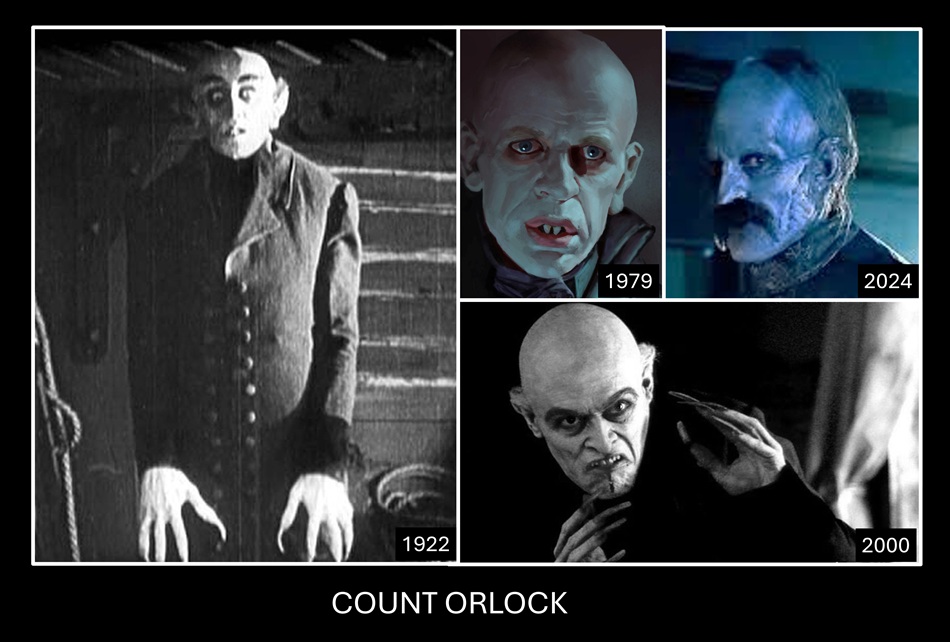

20 vampire films, all first time watches for me.

Come on — sink ’em in.

Boys from County Hell (2020) – Prime/ShudderAh, British and British-adjacent horror comedies. When they’re done right, there’s nothing better, and this one is done right.

I had a blast with this one, I’d put it right up there with the likes of Dog Soldiers, Grabbers, Shaun of the Dead, Doghouse, Severance, and The Cottage. They all have something in common; a close-knit group, localized setting, extreme gore, and flowery language.

This one takes place in Northern Ireland in a verdant county of farmers, builders and heavy drinkers. Moffat & Son are construction workers, tasked with paving the way for a hugely unpopular bypass that is not only going to tear up some fields, but will also destroy a long-standing cairn said to be the resting place of a vampire. The legend hangs so thickly in this county that Bram Stoker himself was influenced by it when passing through, and was compelled to write a book. Indeed, the local pub is called the Stoker and garnished with Spirit Halloween props to draw the tourists in.

Naturally, once the cairn is indeed demolished, all hell breaks loose, and the Moffats, along with their friends and colleagues, must survive the night against a terrifying entity.

The horror is indeed horrific, with the usual viscera spiced up with some truly ghastly blood weeping (from every orifice), and Robert Strange (known for orcs and aliens) is suitably creepy as Abhartach, the vampire. The rest of the cast is stellar, with my personal favorites being Nigel O’Neill (Mandrake) as Francie Moffat, and Louisa Harland (Orla in Derry Girls) as Claire, although I don’t want to downplay the rest of the players — everyone was spot on and their dialogue cracked me up several times.

Really enjoyed this one — highly recommended.

9/10

Twilight (2008) – PrimeI guess this watch-a-thon is as good a time as any to view this one, a film as adored as it is vilified. I really don’t have any strong feelings either way about this film; I didn’t think it was very well made, but I didn’t hate it, so I think I’ll just address the big issues that swirled around it at the time.

Sparkly vampires: Meh, not a deal-breaker. I actually didn’t mind this idea as it was in keeping with Stephanie Myer’s new vampire mythology. I wasn’t a big fan of all the brooding though — definitely a case of too many surly faces.

Rob Patts and Kris Stew: I really like these two — Pattinson was my favorite actor in 2019 (The Lighthouse), and Stewart has been solid from Underwater onward. However, in this film they are not directed well and come off as overly miserable, more than they needed to be.

Team Jacob: Ah, bless him.

Vampire skills: The super-speed and wire work were awful (SFX-wise), especially for a 2008 film. And I didn’t see a single fang. Boo.

The tone: Hated the colour-grading, Catherine Hardwicke’s direction was bafflingly stuffed with nonsensical camera moves, and the editing was dire. Stilted, awkward dialogue. Also, dull narration.

Good points: I really liked the dynamic between Bella and her estranged dad (Billy Burke, excellent), and of the Cullens Alice (Ashley Greene) was fun.

I am fully aware that I’m not the intended demographic for this film, but there have been plenty of other YA romance flicks with supernatural elements that I have enjoyed a lot more.

Oh well, crossed off the list.

6/10

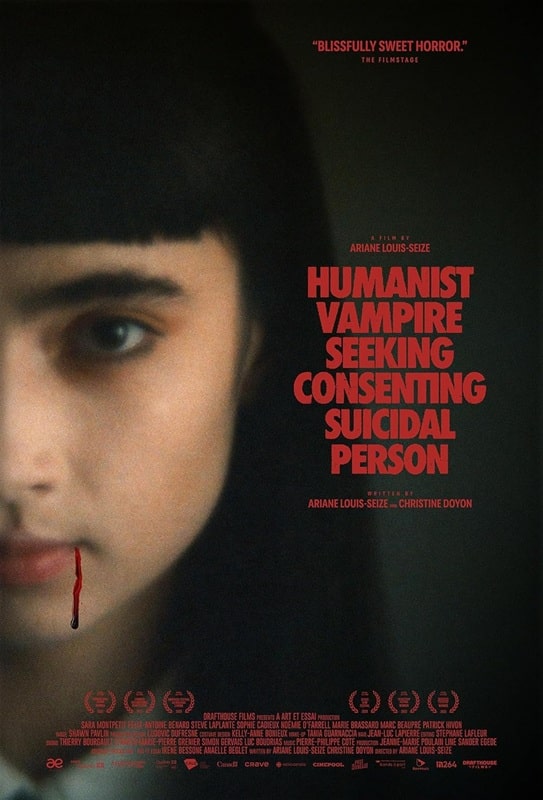

Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person (H264, September 3, 2023)

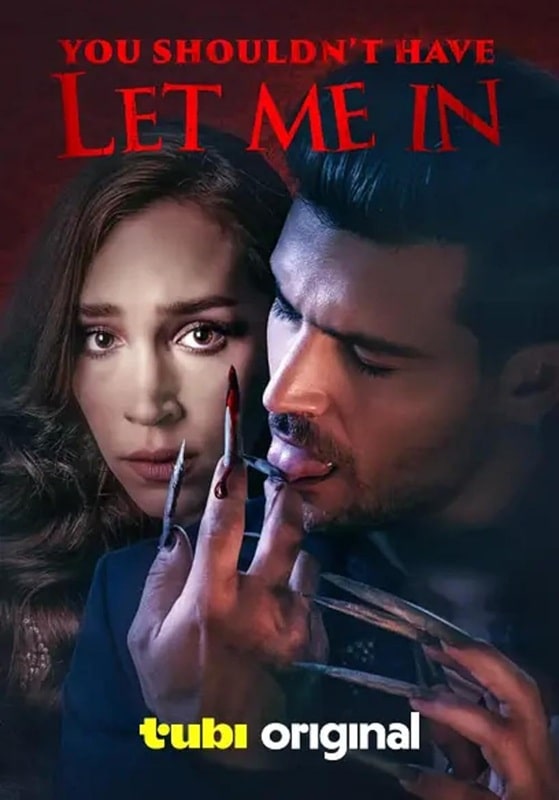

and You Shouldn’t Have Let Me In (Alenu Entertainment, March 15, 2024)

This is a French Canadian film, as is evident by the liberal use of subtitles and poutine.

Sasha is a teenage (68) vampire, part of a loving family who are concerned that she still hasn’t killed her first human. Problem is, Sasha doesn’t want to. She gets sick at the idea, and prefers to slurp from blood bags while brooding around town in the evenings. Eventually her family intervenes, and she is sent to live with her more bloodthirsty cousin in the hope she can be weaned off the bags and onto jugulars.

Sasha is having none of it, and continues to despair, until she runs into a young man who is tired of life. This is Paul, a lonely and picked-upon high schooler with a fondness for rocks and a personal bully who fills his shoes with queso. Sasha and Paul appeal to each other’s plight, and a plan is hatched to help Paul fulfill his final wishes before Sasha finally earns her fangs.

This film is a vibe. By which I mean if you like awkward non-romances with furtive glances, unsubtle metaphors, sitting on the edge of beds, symmetrical compositions, good lighting, a great soundtrack, and the occasional neck-nibble, this is for you. Did I mention it’s hilarious? Well it is, in a gently dark way. Its look is simultaneously harsh and dreamlike, and the two leads (Sara Montpetit and Félix-Antoine Bénard) are perfect (if this was remade in the U.S., the leads would be Kristen Ritter and Nicholas Hoult).

I loved it — but your experience may differ.

9/10

You Shouldn’t Have Let Me In (2024) – TubiAwkward title aside, this has all the tiresome social media subplots you would expect from a 2024 film. A bunch of old friends meet up somewhere in Italy for Rochelle’s wedding to Richard, former boyfriend of main protagonist Kelsey. Kelsey has arrived with her gay best friend, Blake, and they join Rochelle and bachelorette party organizer Jenny on the beach. Kelsey isn’t wearing the right attire to be in any of their photos (Rochelle has her 123 million followers to think of) so she wanders off into town where she meets Gianni, the resident Van Helsing, who warns her of ‘evil’ and gives her Chekov’s pendant.

Of course, Kelsey meets Victor (do vampires have any other names? I’d love to see a vampire called Nigel), who is the owner of the villa they are all staying in. Absurdly, Victor has to wait for them to invite him into the building he owns, and from that moment on, he pursues Kelsey (who is the spitting image of his centuries-old lost love) while the others scramble about.

It’s all extremely unoriginal and tiresome. Rochelle doesn’t want to call the cops (after finding her murdered friend) because that will impact her follower count, Blake just wants to get into Gianni’s pants, and Victor is the least charismatic count I’ve ever seen, all blinding white teeth and Jason Priestly hair.

There are parts that I enjoyed; the direction is decent, the setting is suitably gothic, and Kelsey and Blake are quite fun to watch, but overall it’s a bit of a Mills & Boon arm-chewer.

5/10

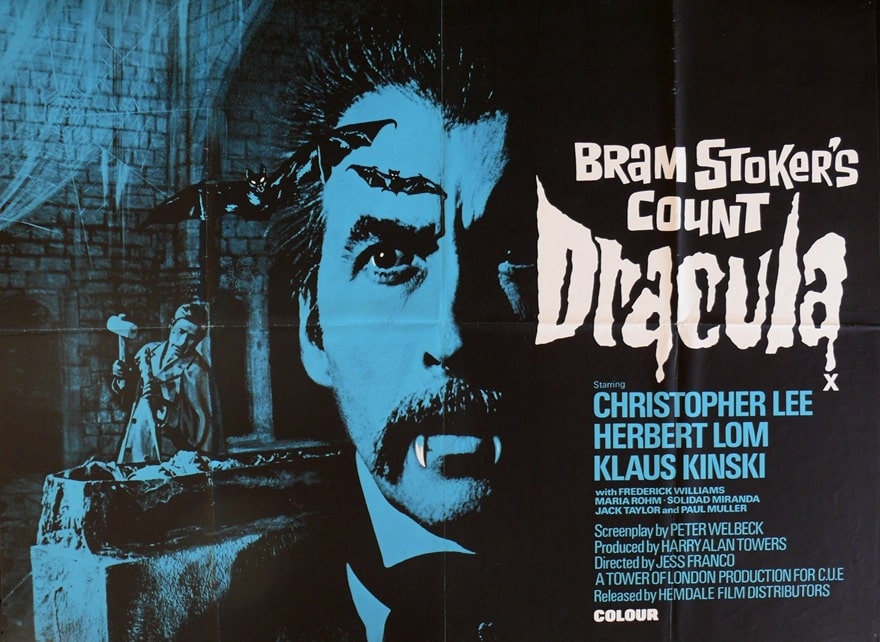

Count Dracula (Hemdale, 1970)

Count Dracula (1970) – Tubi

Count Dracula (Hemdale, 1970)

Count Dracula (1970) – Tubi

Billed as a slavish reenactment of the original Bram Stoker novel, Jess Franco’s take on the story reveals why Dracula works better when it’s adapted with a little pzazz. True, Coppola also stuck closely to the original text, but he was wise enough to sprinkle in plenty of hot actors, rampant knockers, and Tom Waits.

This version, faithful as it is, is rather dull and (somewhat appropriately) lifeless. Big Chris Lee takes it all very seriously, and you can tell this film was important to him after the lurid camp of his glorious Hammer films (which he wasn’t finished with), but this results in a limp-fanged count with barely any physical presence. Herbert (Phantom of the Opera) Lom is fine as Van Helsing, and Klaus (Nosferatu) Kinski was an inspired choice for Renfield, but neither actor was really let off the leash and allowed to demonstrate their natural nuttiness.

Despite some distracting crash-zooms and swish-pans, the film looked quite nice given its abundance of spiders and webs, and I did enjoy Bruno Nicolai’s score, but when all’s said and done, this one was about as memorable as a digestive biscuit.

5/10

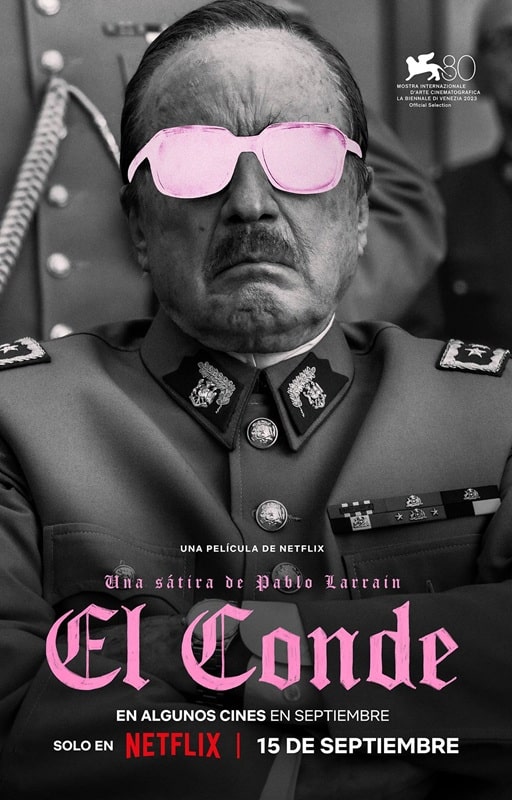

El Conde (Netflix, September 15, 2023)

El Conde (The Count) (2023) – Netflix

El Conde (Netflix, September 15, 2023)

El Conde (The Count) (2023) – Netflix

What a way to end this project. Pablo Larrain, a Chilean director known previously to English-speaking audiences for biopics such as Jackie and Spencer, returns to a subject he previously dissected in an earlier film, No, the subject being Augustus Pinochet, the military dictator of Chile from 1973 to 1990.

However, rather than a narrative formed from the facts of Pinochet’s attempts to cling to power, El Conde takes place in a surreal alternate universe where Pinochet is a centuries-old vampire who has finally grown weary of immortality. His offspring are gathered to his remote estate, along with his wife and man-servant, to discuss his final plans for the division of his ill-gotten gains, but the accountant that has been hired to help is secretly a nun assassin, ready to drive the demon from his soul.

Bickering leads to bloodshed and loyalties are trampled underfoot as the elderly patriarch both yearns for death but also takes off at night to find new victims to sate his taste for heart smoothies (quite literally). It’s as weird as it sounds, and it just gets weirder, especially in the third act when another political figure appears on the scene (there’s a reason why the English narration sounds like Maggie Thatcher).

The film itself, shot in stark black and white, was nominated for an Oscar for cinematography, and it’s easy to see why. Everything, from the use of lighting to the shot compositions, is sublime, and the acting is great all round, not least from Jaime Vadell as the elderly monster.

9/10

Previous Murky Movie surveys from Neil Baker include:

You Can’t Handle the Tooth, Part I

You Can’t Handle the Tooth, Part II

Tubi Dive

What Possessed You?

Fan of the Cave Bear

There, Wolves

What a Croc

Prehistrionics

Jumping the Shark

Alien Overlords

Biggus Footus

I Like Big Bugs and I Cannot Lie

The Weird, Weird West

Warrior Women Watch-a-thon

Neil Baker’s last article for us was Part II of You Can’t Handle the Tooth. Neil spends his days watching dodgy movies, most of them terrible, in the hope that you might be inspired to watch them too. He is often asked why he doesn’t watch ‘proper’ films, and he honestly doesn’t have a good answer. He is an author, illustrator, teacher, and sculptor of turtle exhibits. (AprilMoonBooks.com).

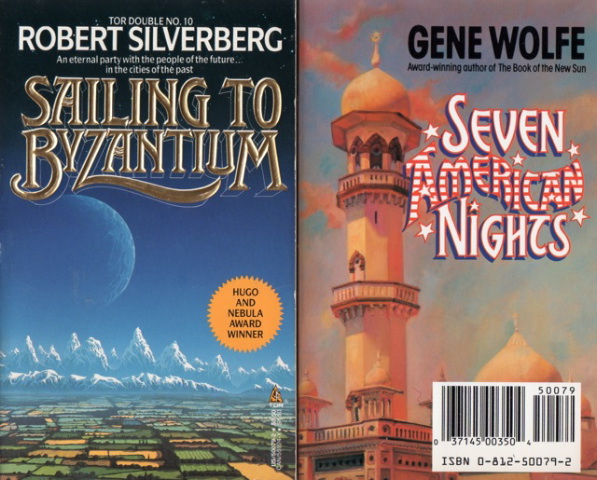

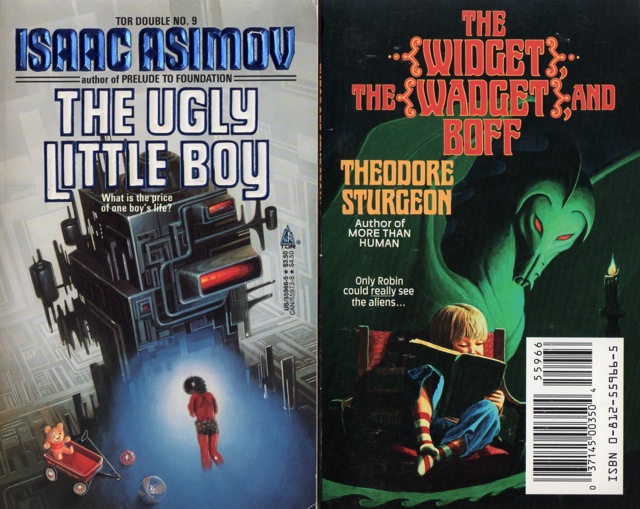

Tor Double #10: Robert Silverberg’s Sailing to Byzantium and Gene Wolfe’s Seven American Nights

Cover for Sailing to Byzantium by Brian Waugh

Cover for Sailing to Byzantium by Brian WaughCover for Seven American Nights by Bryn Barnard

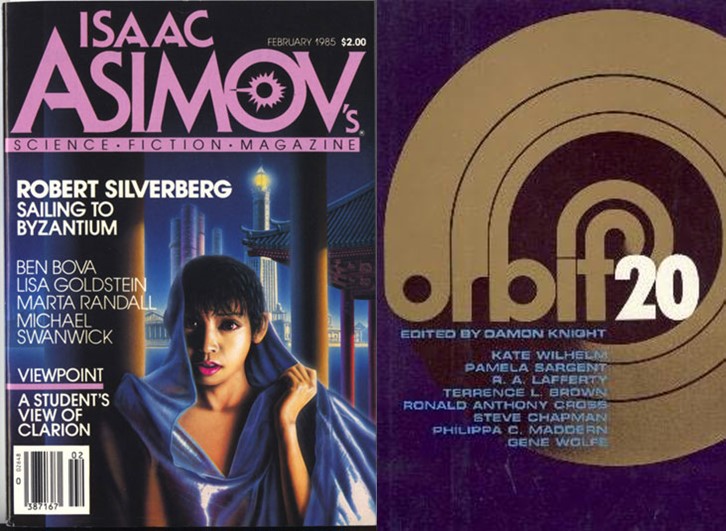

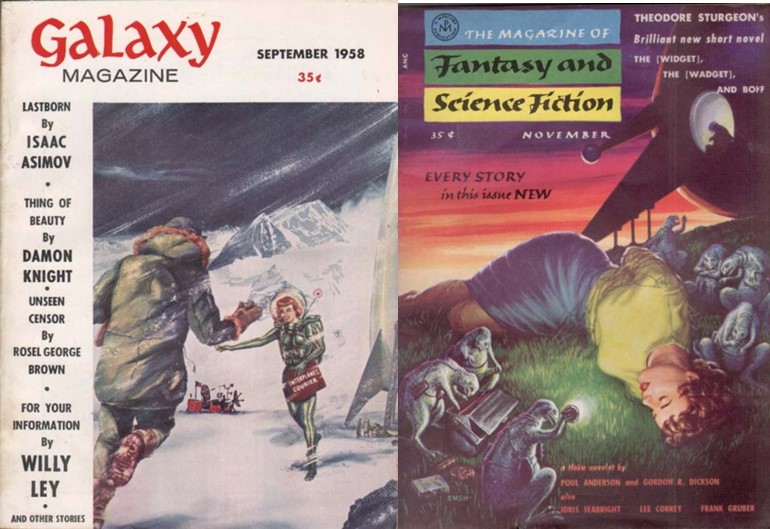

Seven American Nights was originally published in Orbit 20, edited by Damon Knight and published by Harper & Row in March, 1978. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award. Seven American Nights is the first of two Wolfe stories to be published in the Tor Doubles series.

Sailing to Byzantium was originally published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in February, 1985. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award, winning the latter. Sailing to Byzantium is the second of five Silverberg stories to be published in the Tor Doubles series and aside from the proto-series Laumer novel, it is the first time an author has been repeated.

Wolfe’s story opens with a short note from Hassan Kerbelai indicating that he is sending the travelogue of Nadan Jaffarzadeh back to his family, noting that Jaffarzadeh seems to have gone missing. The final paragraphs of the story are focused on Jaffarzadeh’s mother’s reaction to the travelogue. The majority of the story is Jaffarzadeh’s description of his first week visiting America.

The American Jaffarzadeh is visiting, however, is one in which the United States failed generations earlier. The Washington, D.C. he travels through is referred to as the Silent City, containing the remnants of the great federal buildings. Although he travels through the ruins and visits a park that he warns is dangerous, the majority of his time in Washington is spent attending the theatre.

During his first day of touring, he notices a man working in one of the buildings in the silent city. He runs into the man at the theatre and learns that he is working on a machine that can emulate handwriting, essentially what we would recognize as an AI with an autopen ability.

After that early visit to see a production of Gore Vidal’s Visit to a Small Planet, he develops an infatuation for the leading lady, Ardis Dahl. That infatuation drives the remainder of the narrative as he begins to stalk her, attending subsequent nights at the theatre, trying to find where she lives, and eventually meeting one of the other actors, Bobby O’Keene, who offers to introduce Jaffarzadeh for a price. When O’Keene tries to pick Jaffarzadeh’s pocket, the police become involved, O’Keene is arrested, and eventually, Dahl tracks down Jaffarzadeh to get his help releasing O’Keene.

The story is told in the form of Jaffarzadeh’s journal, beginning with his arrival aboard a ship and ending after he begins a relationship with Dahl. However, Wolfe introduces several subtle clues throughout the story, in his choice of plays, the descriptions of characters, and incongruities in the way Jaffarzadeh describes things, that indicate that the seemingly straightforward tale is much more convoluted that it would appear.

Upon reading the story, it appears that Jaffarzadeh is somehow the victim of a scam perpetrated by the acting troupe, possibly in conjunction with the manager of the hotel who first sent him to the theatre. However, Wolfe’s choice of plays, one that deals with a traveler attempting to provide a war, the other about a woman who vanishes, indicate that something far more sinister is taking place. Two of Jaffarzadeh’s fellow passengers to America make appearances late in the story. Are they part of the plot? Are the police involved? What about the functionary who sent the journal on to Jaffarzadeh’s family? Wolfe doesn’t offer any real answers and the text, itself, can offer up a Rashomon-like series of answers, none of them more correct than the others.

Seven American Nights feels incomplete. Not only does Wolfe not provide answers to the many questions that are implied, but rarely stated, but he ends the story with Jaffarzadeh’s mother’s not knowing his fate, but knowing he is alive. The reader, on the other hand, is not so sure. Even if Jaffarzadeh can be trusted, and by his own words he notes that he hasn’t included the entire story and has removed pages, the possibility that someone else, possibly even the machine his friend was working with, wrote parts of the journal mean it cannot be trusted.

The described arrest of O’Keene after he tried to pickpocket Jaffarzadeh, in which it is clear that if Jaffarzadeh doesn’t swear out a complaint, the police will arrest him anyway and trump up the charges, coupled with the inability to discover where he is being kept or what happened to him, has chilling parallels with the current situation in which ICE is arresting people and deporting them without due process. Within the context of the story, it also sets the expectation that if the authorities determine that Jaffarzadeh must be removed, there is nothing that anyone could do to stop them or reverse his arrest.

The strength of Seven American Nights is the very infuriating ambiguity with which Wolfe has carefully laced the story.

Issac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine February 1985 cover by Hisaki Yasuda

Issac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine February 1985 cover by Hisaki YasudaOrbit 20 cover by an unknown artist

The strength of Seven American Nights is the very infuriating ambiguity with which Wolfe has carefully laced the story.

Silverberg’s world of Sailing to Byzantium is reminiscent of the fin du siècle decadence of Michael Moorcock’s Dancers at the End of Time, which I recently re-read. While Moorcock viewed the world of ever-changing landscape from the point of view of one of the period’s denizens (or citizens as Silverberg calls them), Silverberg’s protagonist, is in the time traveling role of Moorcock’s Mrs. Amelia Underwood. This change makes Silverberg’s world more interesting since it allows the story to offer its own contemporary judgement of the citizens’ self-indulgence.

Of course, Silverberg’s story shares its title with a poem by William Butler Yeats in which Yeats also explores the concepts of immortality, art, and the idea of a paradise. Silverberg has selected as his point of view Charles Phillips, who, without knowing how or why, has been pulled from twentieth century New York to this new world. Phillips moves from city to city accepting of the immortality which seems to exist for the citizens and trying to find his own place among the glories or the past recreations.

When the story opens, he is visiting Alexandria at its height, exploring the Pharos and the library in the company of his lover, Gioia. During this visit, Phillips shares with the reader what he knows of this world. The population of citizens numbers in the low millions. Only five cities exist at any time and they are recreations of historic cities, at the moment the novella begins they include New Chicago, Alexandria, Changan, Asgard, and Timbuctoo. Eventually one of those cities will be dismantled and replaced with another city. These citizen are staffed by “temporaries,” sort of synthetic humans or automatons, Phillips isn’t entire sure.

Even as he enjoys the climb to the top of Pharos, he yearns for a Byzantium which hasn’t been built, but which he is sure will be in time. Before it can be, he and Gioia travel to Changan to enjoy the court of the Chinese Emperor. Their visit there is made more memorable by the fact that Gioia’s friends have arranged from them to be treated as honored guests by the Emperor. During their visit, Phillips begins to see the world beyond the façade. When the Emperor, who is merely a temporary, is not actively engaging, he practically seems to turn off.

The real surprise comes we he sees signs of aging in Gioia, something that shouldn’t happen to the immortal citizens of this era. Gioia leaves him, but arranges for him to have a friend, Belilala, as a companion. Unable to understand what is happening, Phillips chases after Gioia, learning from Belilala that Gioia is a rarity, a citizen who can age and die. Phillips chases after Gioia, despite her stated desire not to see him, reminiscent of Silverberg’s own Born with the Dead, which was the first of Silverberg’s novels to be reprinted in the Tor Double series.

Phillips quest of Gioia introduces him to two other visitors such as himself. The first, Francis Willoughby, is from the late sixteenth century and can’t fathom of the world of miracles Phillips attempts to describe them living in. He is convinced he was simply drugged and dragged to an India ruled by Portuguese (they meet in a recreation of Mohenjo-daro, which replaced Timbuctoo). The second visitor Phillips meets is from a period in his future. Y’ang-Yeovil of the Third Septentriad. Y’ang-Yeovil reveals more about the mechanics of the world, and the manner in which visitors are brought into it, causing Phillips to have an identity crisis of his own.

Eventually, Phillips is able to confront Gioia about her desertion of him and her own aging. While Phillips may be a minority as a visitor, Gioia is a very different type of outsider. A citizen, her recessive trait that causes her to age means that she is still seen as an outsider with little recourse or others who share her affliction. Phillips actually quotes the Yeats poem and Byzantium becomes a promised land where a solution to her affliction might become a possibility, allowing Gioia and Phillips to have a life together without worry of out-aging the other.

The world Silverberg built is a strangely ephemeral world in which the only permanence are its citizens. He focuses on two individuals who lack the immortality that almost everyone else in the world enjoys, and each of them must figure out how to come to terms with that fact in their own way, both coming from very different places. Although it doesn’t seem likely, their story introduces true affection into the world.

Some of the novellas collected in any given volume of Tor Double have links to each other. In the case of this book, both the Wolfe and Silverberg novellas are travelogues of a future earth, with Wolfe exploring the remnants of a post-US Washington and Silverberg looks at a future world that recreates the past.

The cover for Sailing to Byzantium was painted by Brian Waugh. The cover for Seven American Nights was painted by Bryn Barnard.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Vintage Empires: James Nicoll on Galactic Empires, Volumes One & Two, edited by Brian W. Aldiss

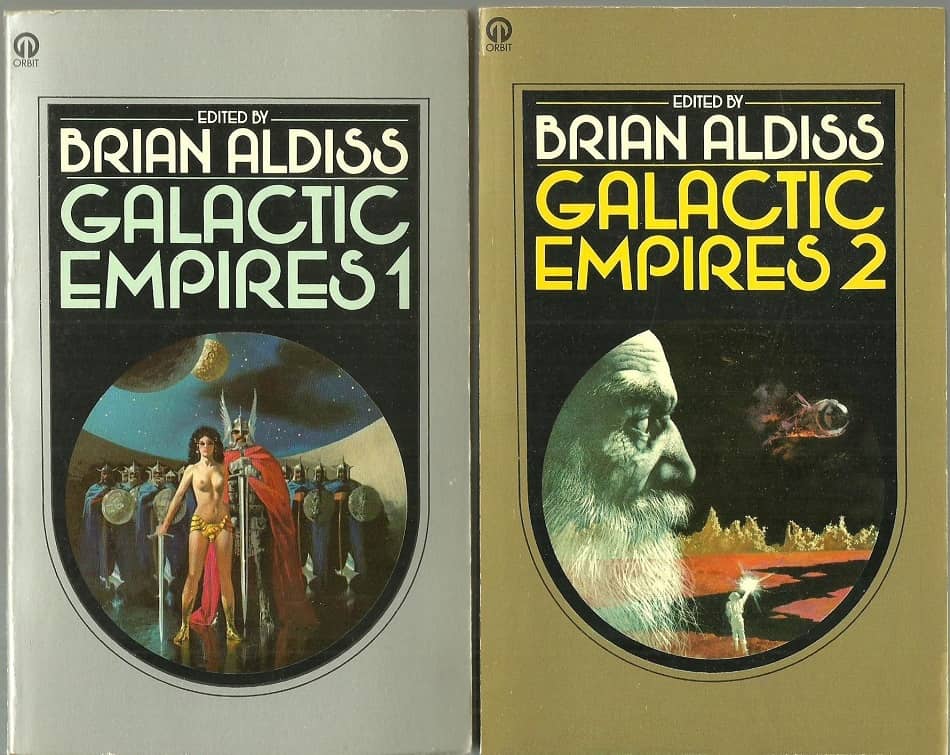

Galactic Empires, Volume One and Two (Orbit, October 1976). Covers by Karel Thole

Galactic Empires, Volume One and Two (Orbit, October 1976). Covers by Karel Thole

My fellow Canadian James Nicoll continues to be one of my favorite SF bloggers, probably because he covers stuff I’m keenly interested in. Meaning exciting new authors, mixed with a reliable diet of vintage classics.

In the last two weeks he’s discussed Kate Elliots’s The Witch Roads, Axie Oh’s The Floating World, Ada Palmer’s Inventing the Renaissance, and Emily Yu-Xuan Qin’s Aunt Tigress, all from 2025; as well as Walter Jon Williams The Crown Jewels (from 1987), Wilson Tucker’s The Long Loud Silence (1952), C J Cherryh’s Port Eternity (1982), and John Brunner’s 1973 collection From This Day Forward. Now that’s a guy who knows how to productively use his leisure time. Not to mention caffeine.

But my favorite of his recent reviews is his story-by-story breakdown of Brian W. Aldiss’s massive two-volume anthology Galactic Empires, which made me want to read the whole thing all over again.

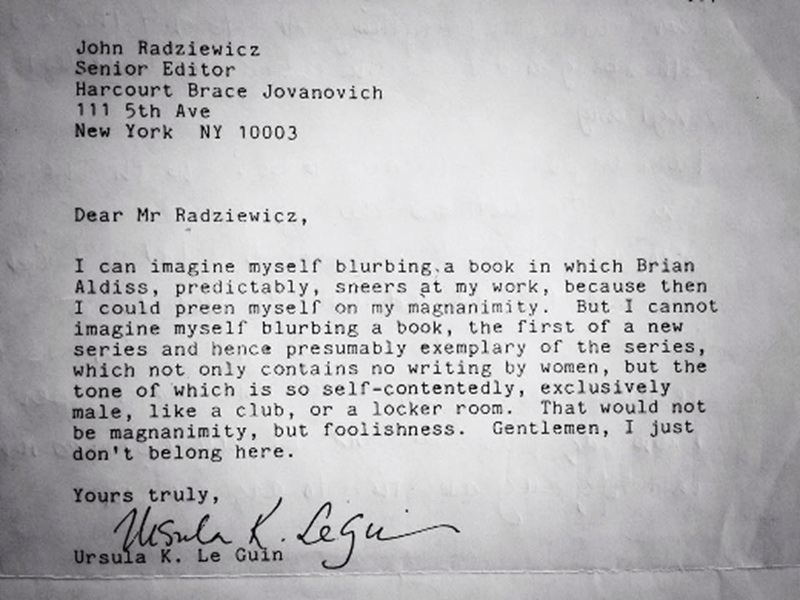

James opens by reprinting the famous letter Ursula K. Le Guin sent to Harcourt senior editor John Radziewicz, when she was asked to provide a blurb for Volume 1 of George Zebrowski’s new anthology series Synergy: New Science Fiction. It didn’t go well.

Ursula Le Guin letter to Harcourt senior editor John Radziewicz

Ursula Le Guin letter to Harcourt senior editor John Radziewicz

As James notes,

Modern readers might be surprised at the almost complete lack of women in the two volumes (or they would be, if the books were not long out of print). Older readers, aware of Le Guin’s response to a later Aldiss-helmed anthology, will be less surprised.

On to the stories.

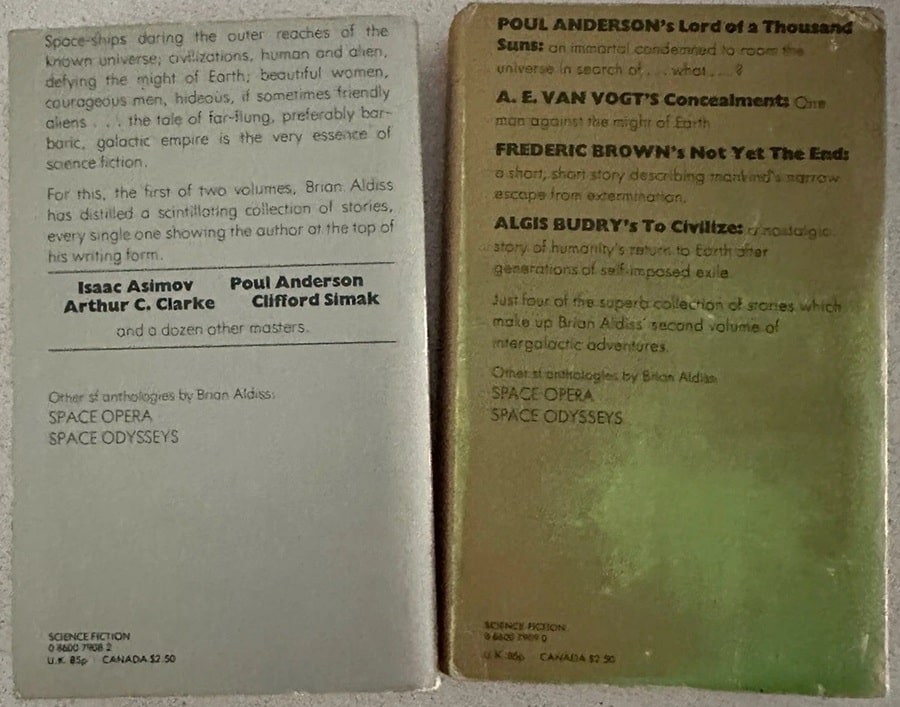

Back covers to the Orbit paperback editions of Galactic Empires, Volume One and Two

Back covers to the Orbit paperback editions of Galactic Empires, Volume One and Two

James covers every one of the stories in this massive anthology. Here’s the highlights.

VOLUME ONEI remembered Volume Two as the stronger of the two. That’s not quite correct. Both have their weak stories (“Foundation,” in the absence of other material, “Escape to Chaos,” not to mention that terrible van Vogt story) but both have works such as “Brightness Falls from the Sky” and “Final Encounter” that I enjoyed encountering again…

“The Star Plunderer” • (1952) • novelette by Poul Anderson — a Technic History story

Alien slavers descent on decadent, weak Earth, little suspecting that their actions will provoke the rise of the TERRAN EMPIRE! The guy does not get the girl. There are enough Anderson Guy Doesn’t Get the Girl stories for an anthology. I wonder why?

“Foundation” (1942) • novelette by Isaac Asimov — a Foundation tale

Endangered due to the slow collapse of the Empire, the Encyclopedists on distant Terminus discover the true reason that their science colony was founded. Without the context of the other Foundation stories, this one seems oddly anti-climactic. Yet it seems to have been wildly popular back when.

“Resident Physician” (1961) • novelette by James White — a Sector General story

What led a terribly ill immortal alien to turn on its physician? And can the staff of Sector General solve the mystery, given they’ve never previously encountered this species? One has to admire how calmly the staff of Sector General take being presented with what amounts to a demigod, especially an angry, apparently homicidal demigod. One of the principal characters in Sector General stories is psychology section-head Major O’Mara, described thusly:

“(O’Mara) was also, on his own admission, the most approachable man in the hospital. O’Mara was fond of saying that he didn’t care who approached him or when, but if they hadn’t a very good reason for pestering him with their silly little problems then they needn’t expect to get away from him again unscathed.”

Has anyone ever proposed a Sector General TV show with Hugh Laurie playing O’Mara?

“Planting Time” • (1975) • short story by Pete Adams and Charles Nightingale

A starfarer stumbles across a potentially profitable and most certainly lascivious previously unknown lifeform. People in the 1970s were extremely horny. No, even hornier than that. However, many men didn’t especially care for that whole needing to chat up partners first nonsense.

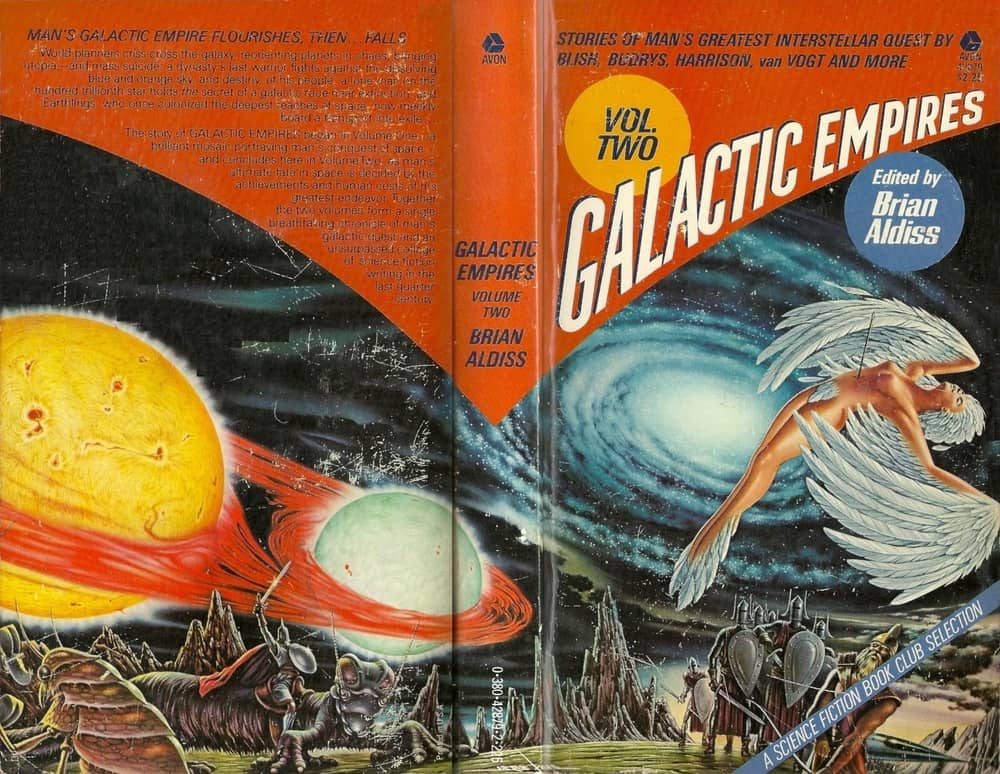

Galactic Empires, Volume Two, US paperback edition (Avon Books, March 1979). Cover by Alex Ebel

VOLUME TWO

Galactic Empires, Volume Two, US paperback edition (Avon Books, March 1979). Cover by Alex Ebel

VOLUME TWO

“Down the River” • (1950) • short story by Mack Reynolds

Humans are, in order, astonished to discover they are subjects of a galactic empire, offended that they are being traded from one empire to another, and alarmed by revelations concerning their new masters. This is an example of a “how would you feel if what you routinely do to others was done to you?” story. It’s not subtle because readers would miss the point if it were and probably most of them did, anyway.

“Final Encounter” • (1964) • short story by Harry Harrison

In the thousand centuries since faster than light drive gave humanity the stars, humans have never encountered intelligent aliens. Now on the far side of the Milky Way, they have. Or so it seems. Whether or not the odd beings are human or not turns out to be surprisingly easy to determine with a simple DNA test, so the big puzzle about which the story is constructed is easily resolved. What I found fascinating as a kid was how Harrison understood that due to the sheer size of the Milky Way (to quote George R. R. Martin):

“There are many ways to move between the stars, and some of them are faster than light and some are not, and all of them are slow.”

“Lord of a Thousand Suns” • (1951) • novelette by Poul Anderson

Humanity’s fate depends on a technological ghost left by a long-dead, all-powerful alien civilization. Anderson is the author I depend on to grasp space and time’s scales, so it’s odd and distracting that his protagonist seems convinced that dinosaurs walked the Earth only a million years ago.

“Big Ancestor” • (1954) • novelette by F. L. Wallace

Many worlds have human races, and while some are more highly evolved than others, all are clearly kin. What glorious race planted colonies in the long-forgotten past? The answer is astounding! Well, technically, the answer is galactic, as this story appeared in Galaxy, not Astounding.

The full review is well worth your time. Check it out here, and do yourself a favor and make it a habit to stop by James’ blog here.

We covered both volumes of Galactic Empires as a Vintage Treasure way back in December 2021.

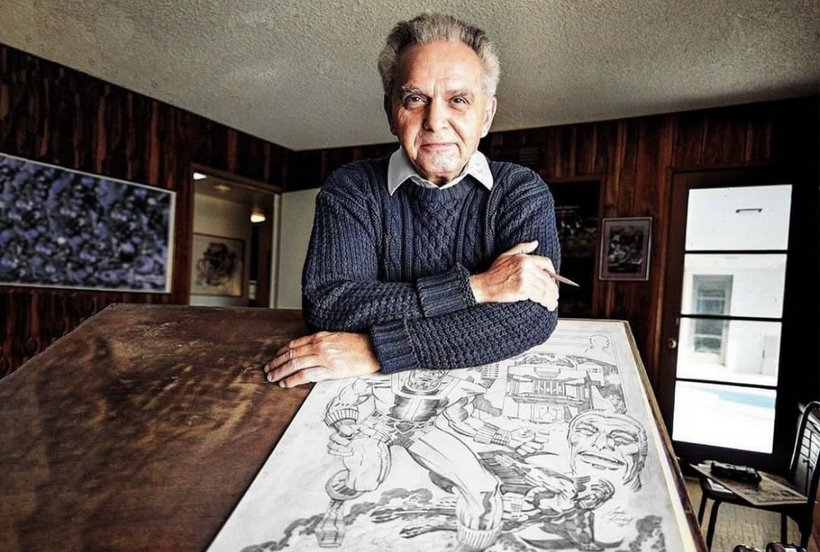

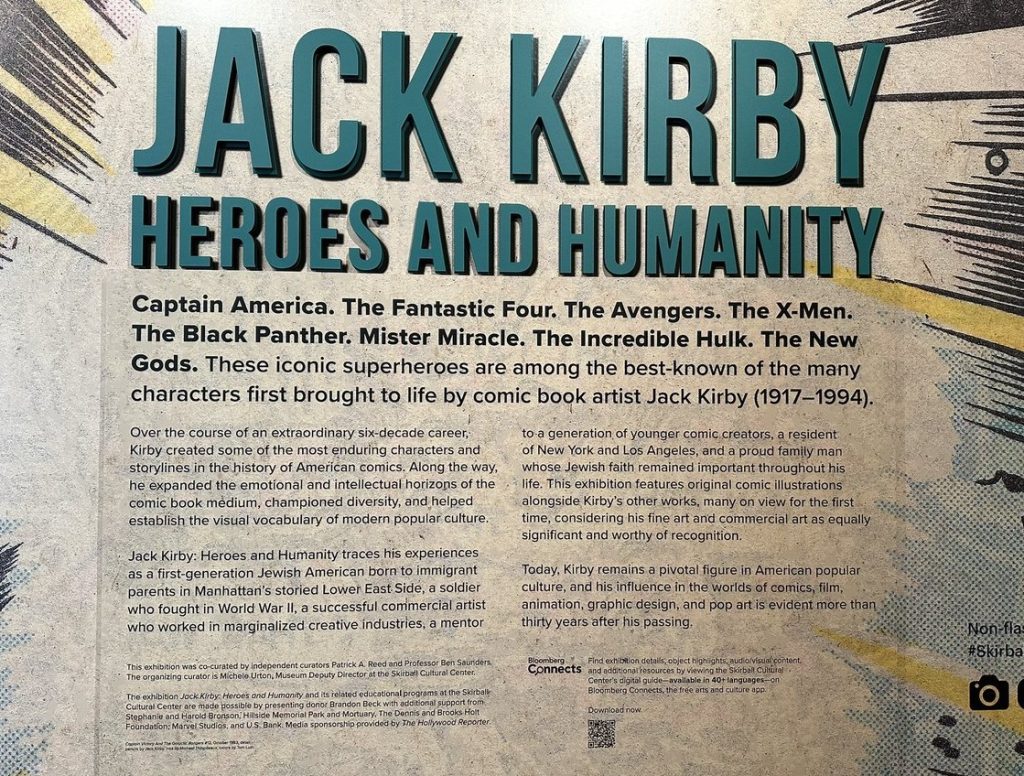

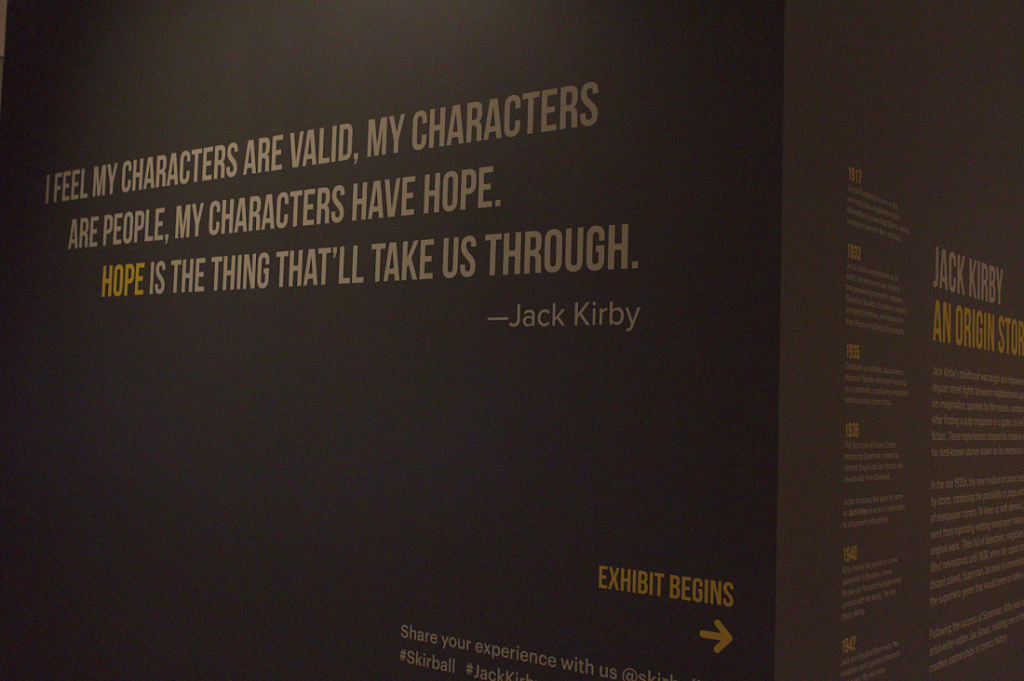

Heroes and Humanity: Jack Kirby at the Skirball Center

Last Friday, as an early Father’s Day gift, my wife arranged for us to spend the afternoon at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, which is hosting a wonderful new exhibition dedicated to the memory and achievement of a great American artist. Titled Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity and running until March 1, 2026, the show is a must-see for any admirer of the King of Comics.

Jack Kirby is arguably the most influential person in the history of mainstream American comic books; his work, more than that of any other artist or writer, defined the visual grammar of the superhero. Along with his partner Joe Simon, he created Captain America in the 1940’s, soldiered through the postwar superhero slump of the 1950’s doing work in all genres — science fiction, war, horror, western, and romance (it’s an often forgotten fact that Simon and two-fisted Jack Kirby created the romance comic book) until, in the 1960’s, when DC showed that there was a reawakening market for costumed heroes, he teamed up with Stan Lee to create the “Marvel Universe”, though they didn’t know that’s what they were doing when they did it.

The King of Comics

The King of Comics

The 60’s saw a flood of characters from Kirby’s pen, most created in collaboration with Lee — the Fantastic Four, Galactus, the X-Men, Thor, Loki, the Black Panther, Ant-Man and the Wasp, the Inhumans, Ka-Zar, MODOK, the Hulk, the Avengers, Iron Man, Doctor Doom, Nick Fury and countless others were the products of his seemingly inexhaustible imagination.

Oh, For Five Bucks and a Time Machine!

Oh, For Five Bucks and a Time Machine!

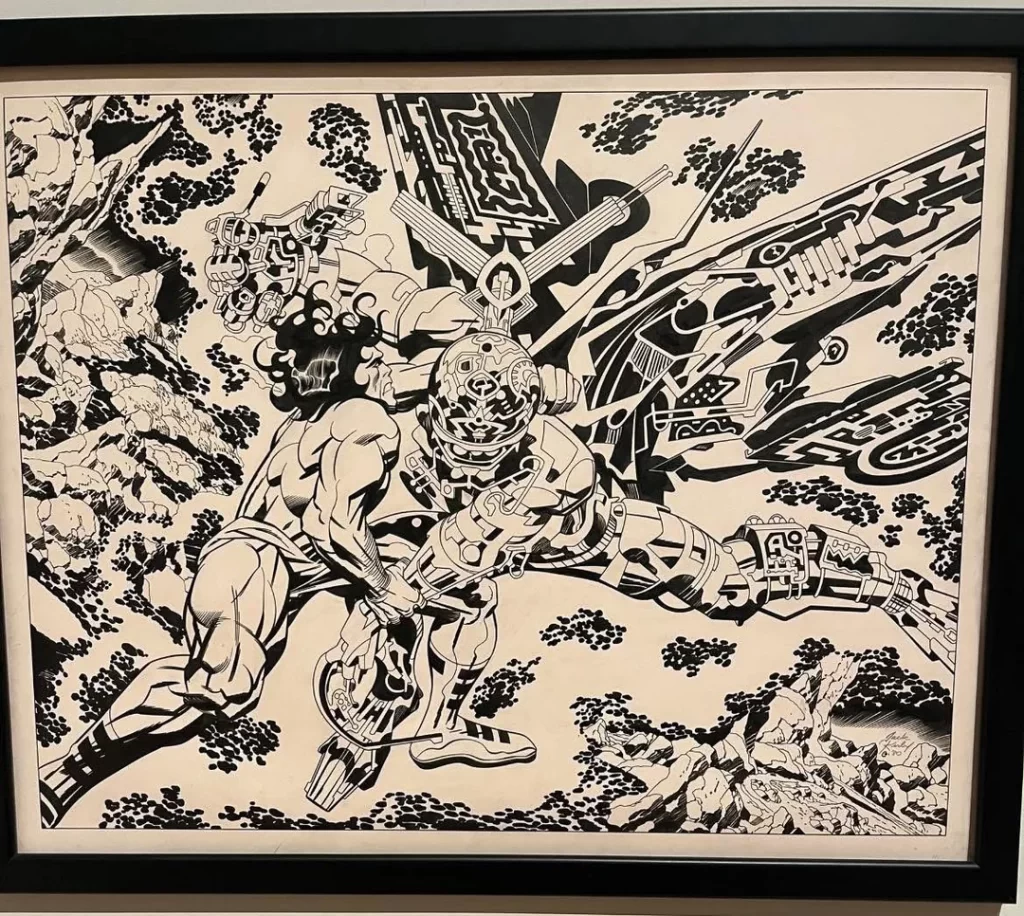

Then, in the 70’s at DC, now working without collaborators, Kirby inaugurated his toweringly ambitious, interlinked “Fourth World” series of comics, with characters such as the New Gods, the Forever People, Mister Miracle and Darkseid, in addition to enduringly popular stand-alone characters like Omac, the Demon, and Kamandi.

Perhaps the greatest indicator of Kirby’s quality is that he took Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen and made it a wild, hip, must-read book; any man who could do that was something special.

Certainly, there have been few American lives of more cultural consequence, and the fact that the mandarins in charge of prestigious museums and artistic institutions are paying attention to people like Jolly Jack is a welcome change from the days when comic book artists rated a little bit lower than the guys who clean out septic tanks. All credit to the Skirball for giving Kirby a place to shine.

The Skirball Cultural Center

The Skirball Cultural Center

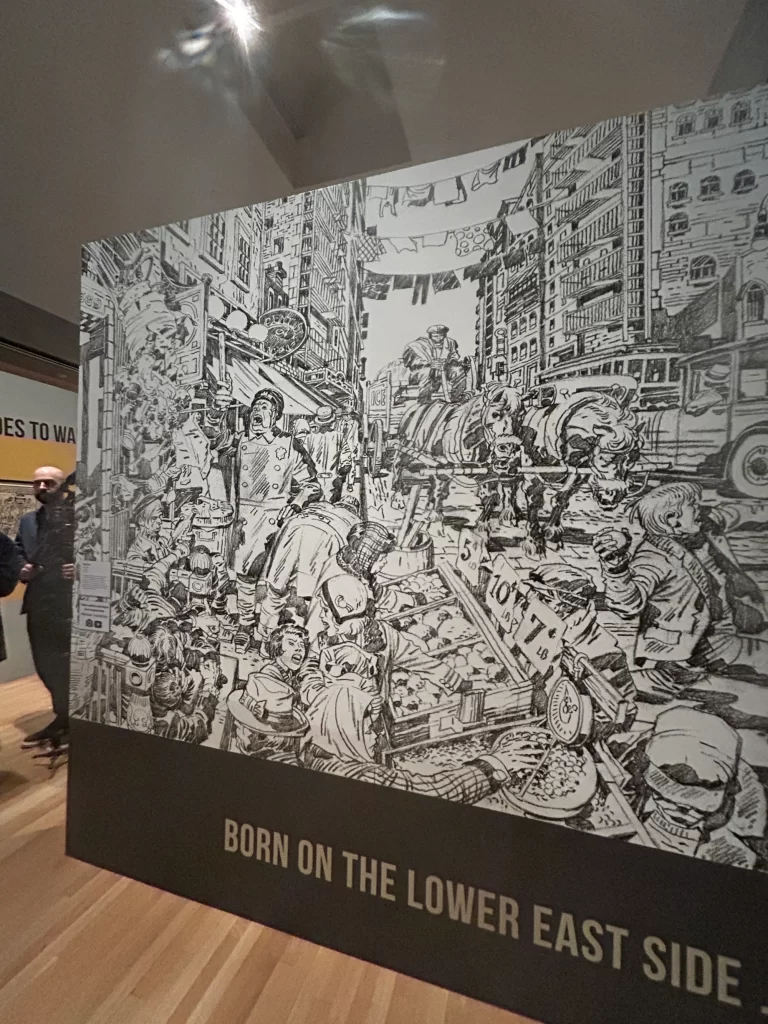

Founded in 1996 and located in the Santa Monica Hills of West Los Angeles, the Skirball Cultural Center is dedicated to celebrating the Jewish experience (especially the American Jewish experience), which makes it an ideal place for commemorating the legacy of Jack Kirby, who was born Jacob Kurtzberg in Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1917. Heroes and Humanity is a first-rate tribute to his life and work.

The exhibit is laid out roughly chronologically; the first thing you see as you enter is a wall-sized reproduction of a Kirby drawing of one of the teeming New York City streets of his boyhood. What follows as you snake your way through to the end is virtually a history of the first five decades of American comic books.

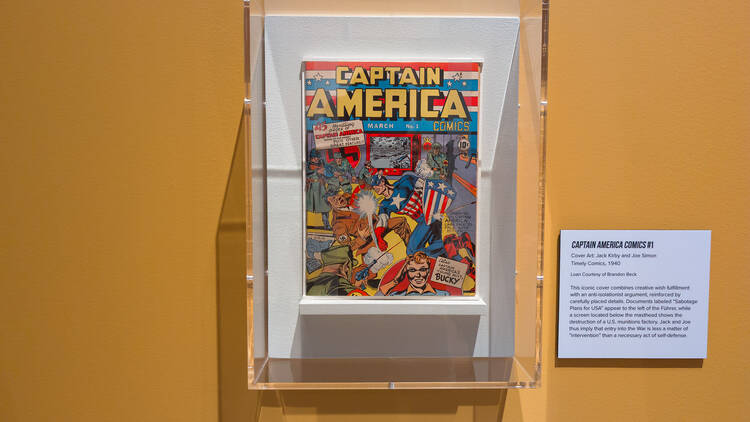

After you turn the corner, at the very first stop (“Kirby Goes to War”), you find yourself face-to-face with one of the most iconic images in all of comic art — the cover of Captain America Comics number one, with Cap giving Adolf Hitler a crack on the jaw, all at the behest of Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, two young Jewish-Americans whose country wasn’t even at war with Germany at the time. One look at this cover leaves no doubt that truth, justice, and the American way (to borrow a phrase from another great hero of the day) were antithetical to Nazism and everything that it stood for, even if the government in Washington hadn’t quite gotten there yet.

Jack and Joe Go to War

Jack and Joe Go to War

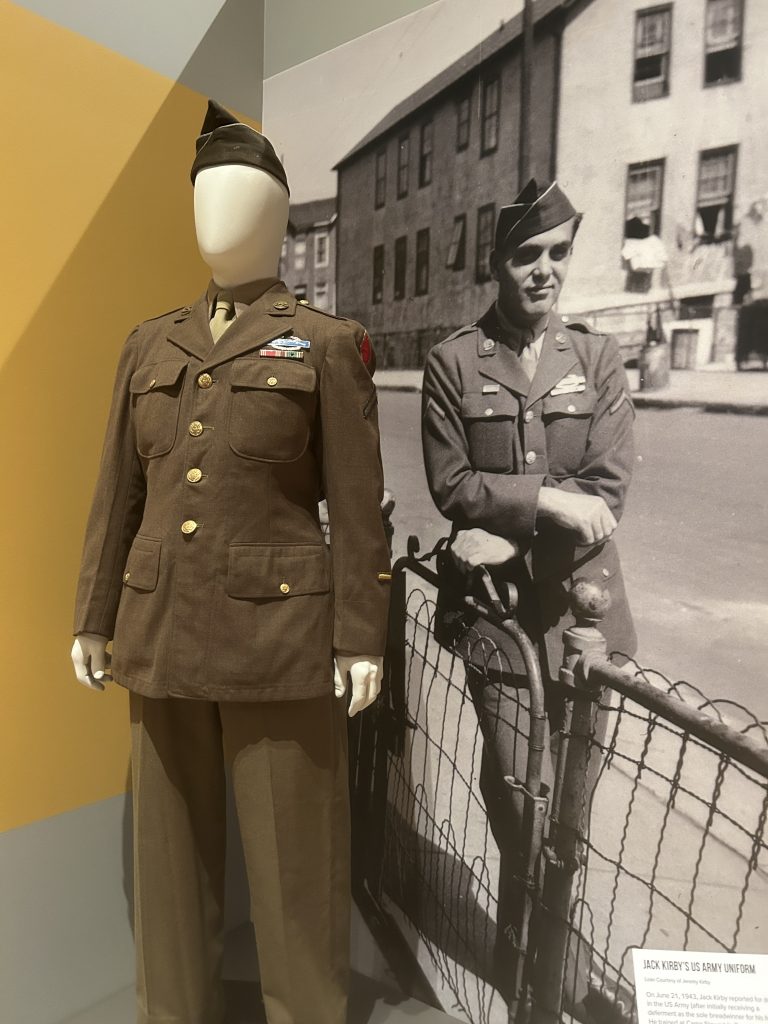

After a reminder that Kirby didn’t confine his opposition to fascism to the four-color page (a prominent place is made for the Army uniform that he wore while serving in Europe during World War Two), the displays take us through the kaleidoscope of genres that Kirby worked in during the postwar years. There are plenty of actual issues of comic books featured, of course, but most of the Skirball exhibit consists of original Kirby art, both published and unpublished.

Private Kirby Reporting

Private Kirby Reporting

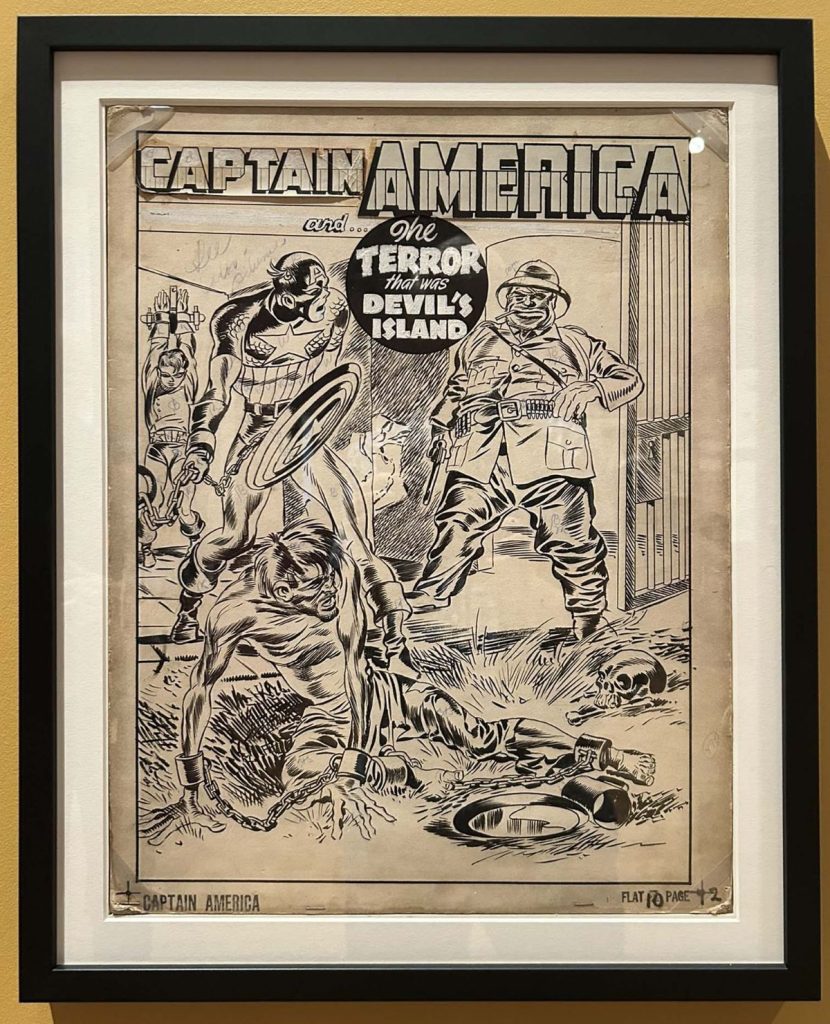

It’s a joy to be able to see this work (much of which has never been shown in public before) close up. Most are inked pages, completed by people familiar to comics fanatics — Joe Sinnott, Mike Royer, Vince Colletta, Bill Everett, Marie Severin, Dick Ayers, Chic Stone — but there are also many uninked drawings, allowing viewers to study Kirby’s legendary pencil technique.

From Captain America Comics #5

From Captain America Comics #5

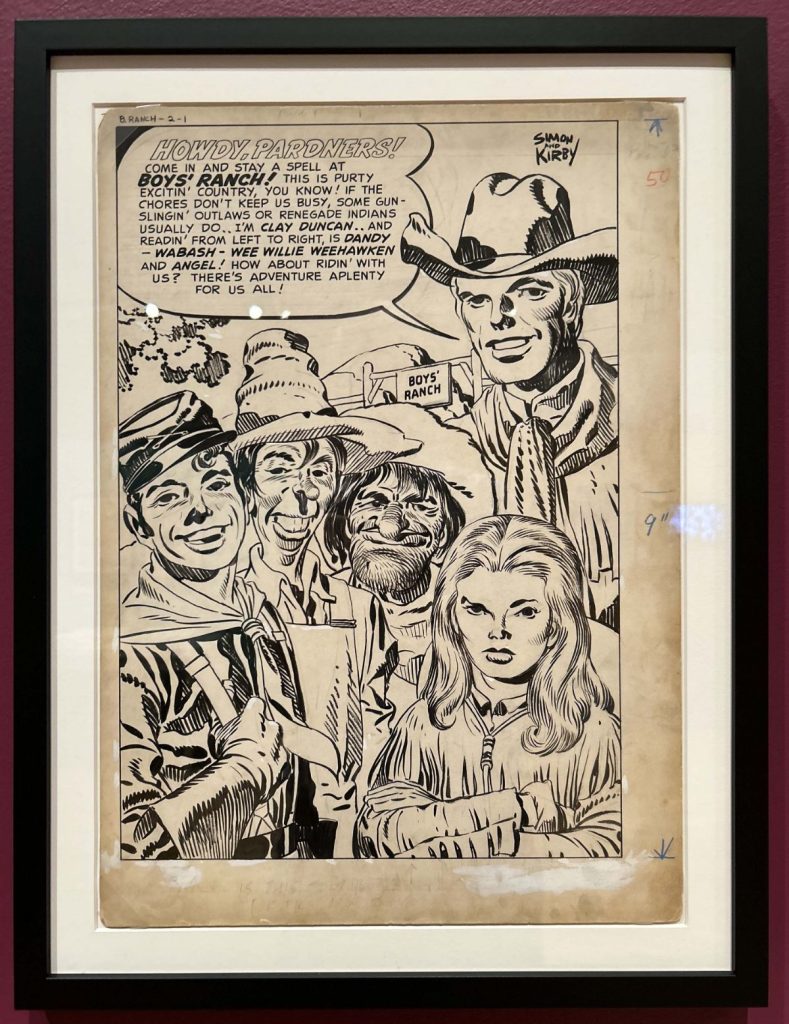

It’s especially nice to see so much of the 40’s and 50’s multi-genre work that Kirby did with Joe Simon, which isn’t as familiar to most people as the King’s later superhero creations for Marvel and DC. I particularly liked a gorgeous splash page, bursting with character and humor, from the western Boy’s Ranch, a title Kirby always cited as one of his favorites.

Boy’s Ranch Splash Page

Boy’s Ranch Splash Page

One section of the exhibit is titled “Kirby’s Stylistic Evolution”, and it traces just that, showing how Jack’s layouts and depiction of character and anatomy developed over time, resulting in bold, polished 60’s and 70’s art that was very different from his vigorous but coarser 40’s and 50’s output, while still remaining recognizably the work of the same man. (Once at the San Diego Comic Con, I heard Neal Adams talk about Kirby. “I didn’t like him”, Adams said. “His people were ugly, and they had big teeth.” Never fear — Adams eventually came around to full-blown Kirby worship.)

Of course, the great years of the Marvel 60’s and the DC 70’s form the core of the exhibit, and there is enough of that work at the Skirball to satisfy the appetite of any member of the MMMS or FOOM (that’s the Merry Marvel Marching Society and the Friends of Ol’ Marvel, if you didn’t know, and if you didn’t know, why didn’t you?)

One huge wall (“Re-Inventing the Superhero”) displays an entire X-Men story, and allows you to compare Kirby’s original art with the finished, colored comic book pages that were snapped up off the newsstands by eager kids in the 60’s, long before the Marvel Cinematic Universe was even a gleam in Stan Lee’s eye. (Stan is treated rather gingerly here — the most noticeable thing is that the standard formulation “Stan and Jack” is changed to “Kirby and Lee”, which in this context is only fair — it’s Jack’s show.)

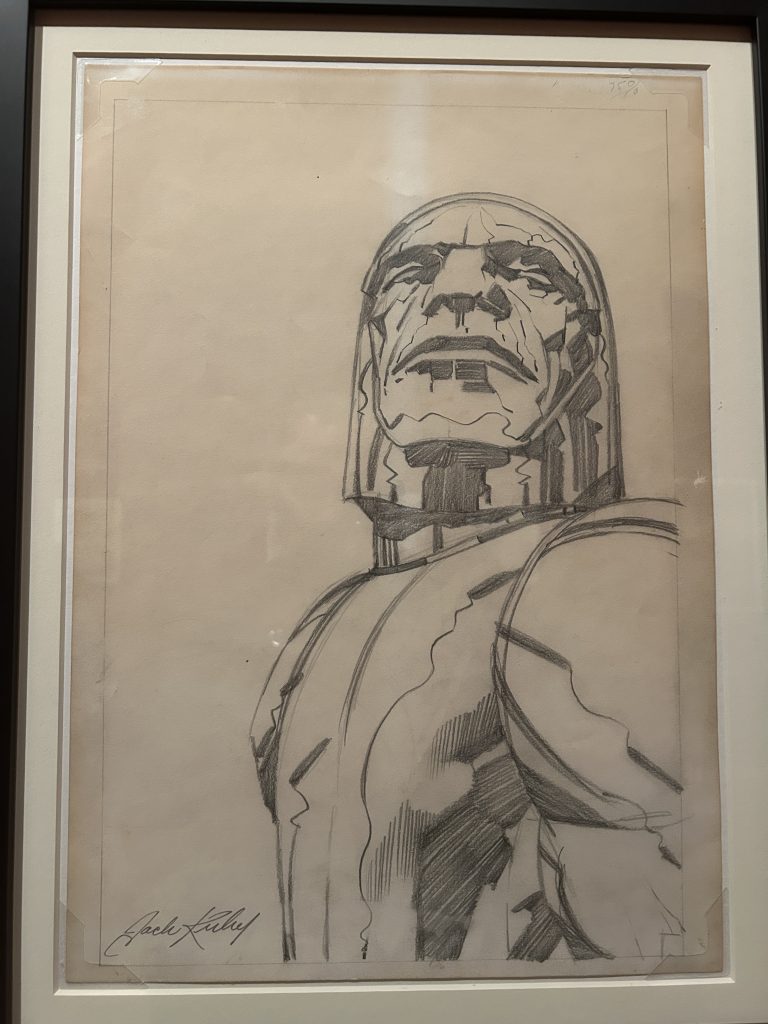

Kirby’s Fourth World art and his other DC characters of the 70’s receive a large share of space, too. I think my single favorite thing in the whole exhibit was a magnificent pencil drawing of the cosmic fascist Darkseid (a character Kirby based on Mussolini), proud, immovable, lost in his dreams of universal dominion. A villain to be sure, but in Kirby’s hands, not just a villain. (I always think of Darkseid’s surprising summing up of the wedding of Mister Miracle and Big Barda: “It had deep sentiment — yet little joy. But — life at best is bittersweet!”)

Darkseid

Darkseid

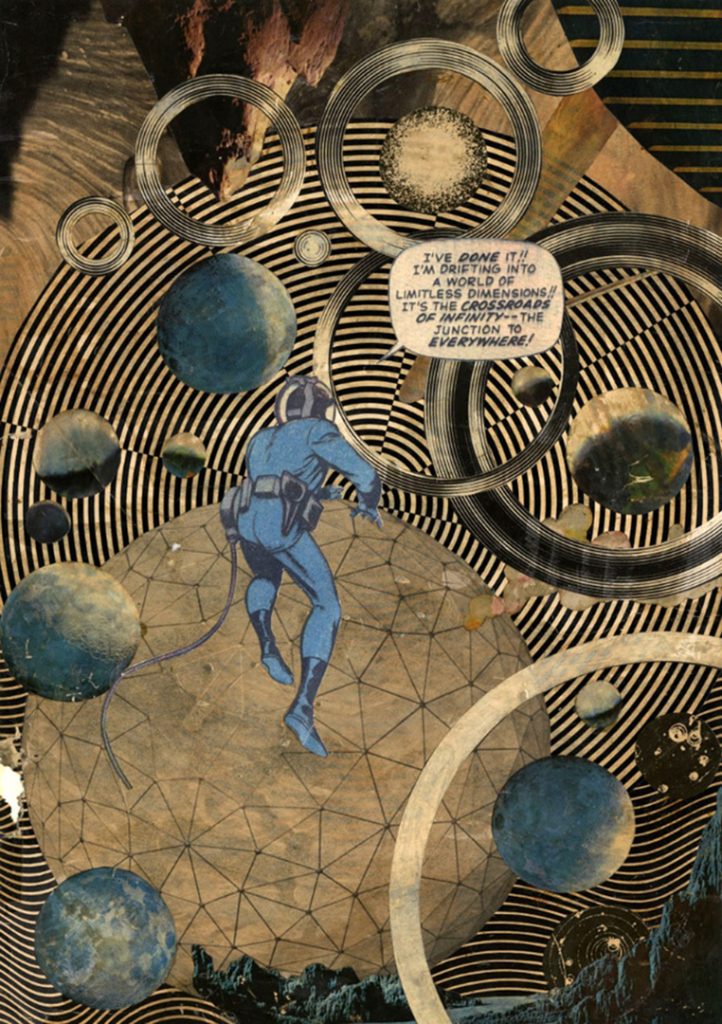

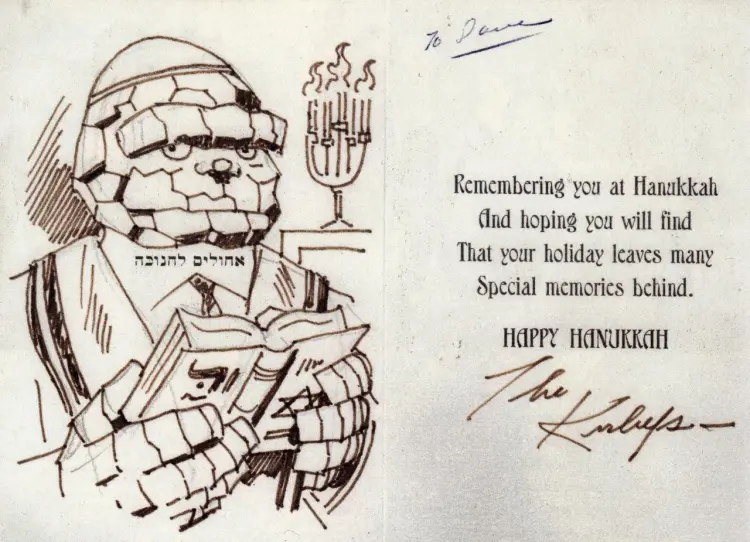

There are several striking examples of Kirby’s non-commercial art, work that he did just for himself or for friends. One of the most eye-catching is his dramatic depiction of the story of Jacob wrestling the Angel from the biblical book of Genesis, and there are several stunning Kirby collages, a form that he seemed especially fond of and that he sometimes integrated into his comic book work. One of the most touching of the personal items is a Hanukkah card that Jack and his wife Roz sent to friends; seeing a yarmulke on the Thing leaves no doubt about what Ben Grimm’s old neighborhood was like. Take that, Yancy Streeters!

There are more treasures at the Skirball than I have room to share with you here; all I can do is urge you to come and see it all for yourself. If you’re in the Los Angeles area any time in the next eight months, be certain to make time for Jack Kirby: Heroes and Humanity. It’ll be time well spent, because Jack Kirby is a man worth getting to know, and he continues to awe, delight, and even teach us.

Into the Negative Zone

Into the Negative Zone

At another one of those long-ago San Diego Comic Cons, at the annual Jack Kirby Tribute Panel (the one event that I made sure I never missed), I heard the great Spider-Man artist John Romita tell a story about the first time he met Jack Kirby.

Jacob and the Angel

Jacob and the Angel

Romita, a young artist just starting out, was in awe of this man who was a living legend. Not knowing what to say to one of his idols, but thinking about Kirby’s brilliant pencil drawings, Romita asked Jack what kind of pencil he used, thinking that the greatest artist in the business would name some fancy imported instrument hand-made out of rare Italian hardwood that cost fifty dollars a box, or something like that.

Jack looked blank for a moment; then he reached into his back pocket and pulled out a plain yellow pencil, the kind you can buy in any drugstore. “A number two”, he said.

He could see from the expression on Romita’s face that this wasn’t the answer the young man was expecting. “Then”, John Romita said, “Jack Kirby said something that changed my life as an artist.”

“John”, he said, “you don’t draw with a pencil.”

Think about that. You don’t draw with a pencil.

Look, Ma — No Pencil!

Look, Ma — No Pencil!

It’s the easiest thing in the world to confuse the tool with the task, but a true artist draws with his mind and his heart, with everything that he is; it’s not graphite or ink or paint that he puts on the page. It’s his soul — that’s why we respond to his work. That’s why it moves us, frightens us, excites us, exalts us, why it grabs hold of us and won’t let go; that’s why we love it.

Jack Kirby, who labored in the lowly comic book industry when that meant being disrespected and underpaid, was a true artist, and if he’s finally getting his due, then there’s hope for us all. Find out for yourself; come and pay him a visit.

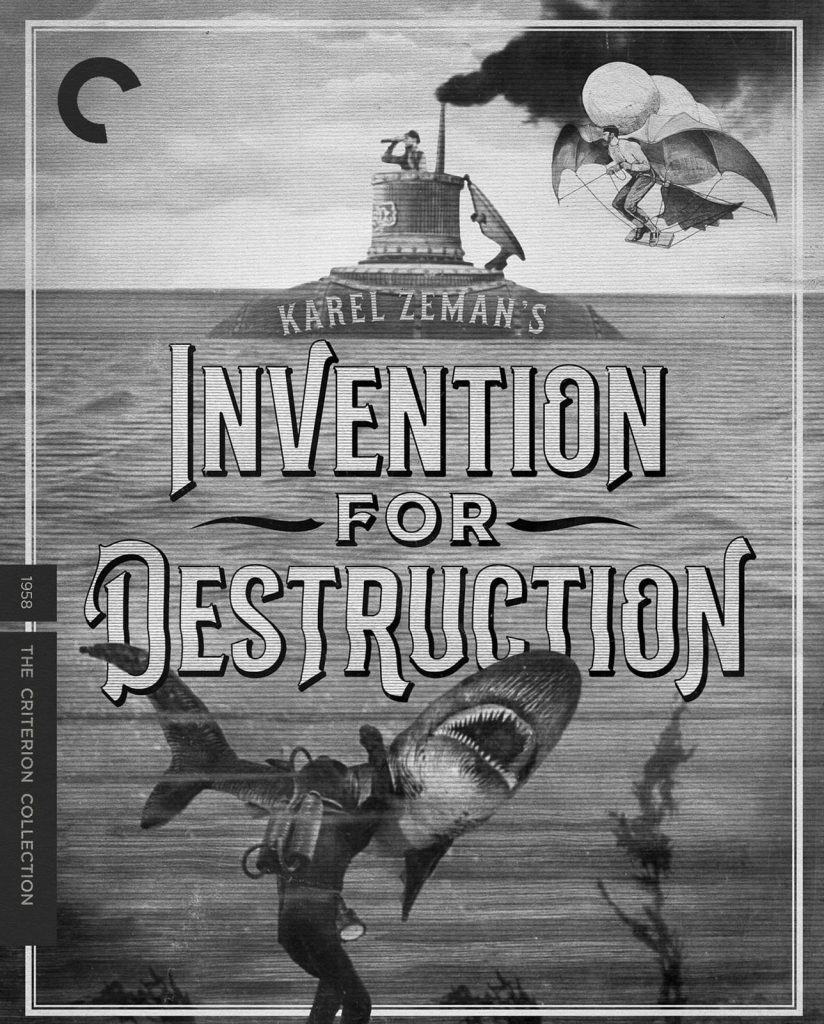

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Hand-Crafted World: Karel Zeman’s Invention for Destruction

The Fundamentals of Sword & Planet, Part I: Don Wollheim, Edwin L. Arnold, and Otis Adelbert Kline

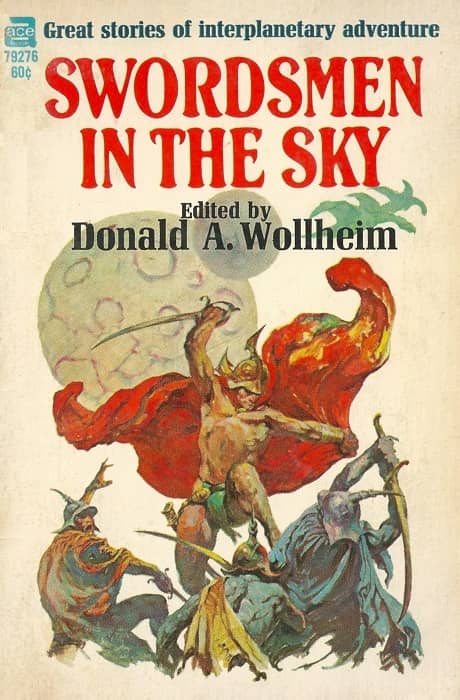

Swordsmen in the Sky (Ace, 1964). Cover by Frank Frazetta

If our genre has a holy grail to find, this would be it. I read this collection as a kid. Found it in our local library. And loved every single story in there. Took me a while to find a copy as an adult but it’s one of my pride and joys.

[Click the images for planet-sized versions.]

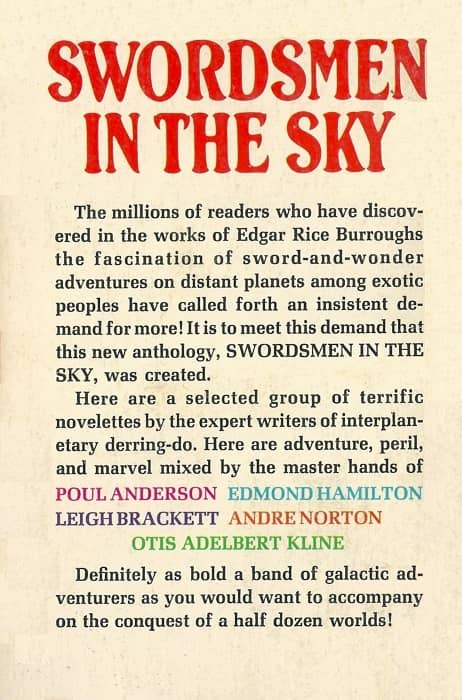

Inside cover and facing page for Swordsmen in the Sky

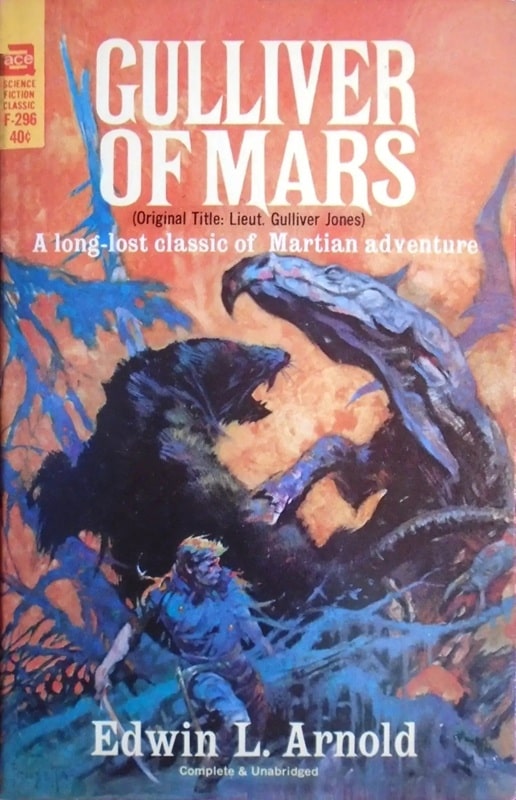

Edgar Rice Burrough’s biographer, Richard Lupoff, in Master of Adventure, suggested that ERB’s A Princess of Mars (1912) was influenced by a 1905 work called Lieut. Gulliver Jones: His Vacation, by Edwin Arnold. Gulliver Jones gets to Mars via flying carpet and finds a lost world, though not a desert world, inhabited by Martians.

There is a princess that “Gully” must rescue, and there’s a journey down a river, but otherwise there’s not a lot of similarities, and Gulliver’s story is a long way from being as compelling and entertaining as ERB’s Princess of Mars.

Gulliver of Mars (Ace Books, 1964). Cover by Frank Frazetta

Having read Lupoff, I sought out Arnold’s book, which was republished after the Burroughs boom began as Gulliver of Mars (1955). After reading that book, I personally couldn’t see anymore than the vaguest of similarities, and there’s no evidence that ERB actually ever read or knew of Arnold’s book.

Still, it’s an interesting curiosity and has a pretty cool cover in the reprint.

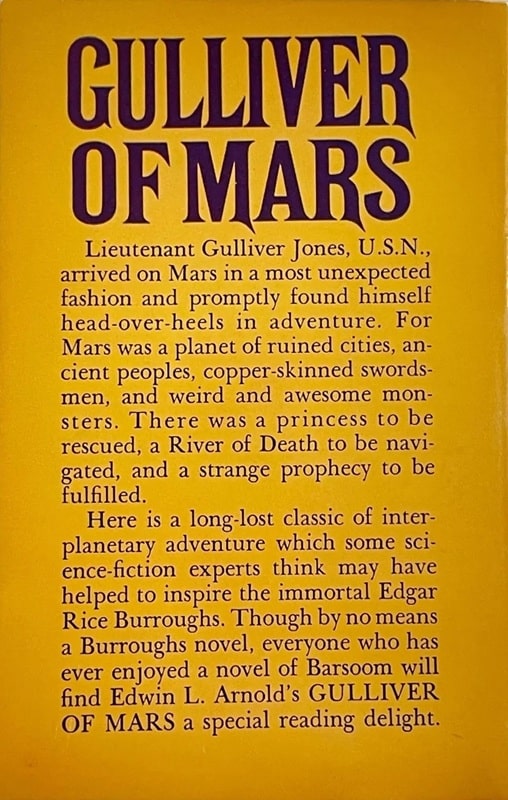

My Otis Adelbert Kline collection: Planet of Peril, The Port of Peril, and Prince of Peril (Ace Books, 1963-1964, covers by Roy Krenkel, Jr.), Maza of the Moon, Jan of the Jungle, and The Swordsman of Mars (Ace, 1965, 1966, and 1961; covers by Frank Frazetta, Stephen Holland, and Ed Emshwiller).

Otis Adelbert Kline

My Otis Adelbert Kline collection: Planet of Peril, The Port of Peril, and Prince of Peril (Ace Books, 1963-1964, covers by Roy Krenkel, Jr.), Maza of the Moon, Jan of the Jungle, and The Swordsman of Mars (Ace, 1965, 1966, and 1961; covers by Frank Frazetta, Stephen Holland, and Ed Emshwiller).

Otis Adelbert Kline

A contemporary of ERB was OAK, Otis Adelbert Kline. He also wrote sword and planet stories, and even jungle adventure. Both men had series set on Mars and Venus, and tales set on the moon. For a long time there were rumors of a feud between the two men but that idea has been generally debunked since no evidence from either party indicates any animosity between the two.

The publication dates of their stories certainly indicates some back and forth between their writings but nothing indicates any emotional intent behind it. I’ve read most of OAK’s stuff and find it fun, although — for me — without as much narrative drive and somewhat less colorful in imagination. OAK is also known to have been Robert E. Howard’s literary agent toward the end of Howard’s life.

Above is a picture of my Kline paperbacks. I have some other books by him in facsimile reprints. The Peril series (set on Venus) is particularly good in my opinion.

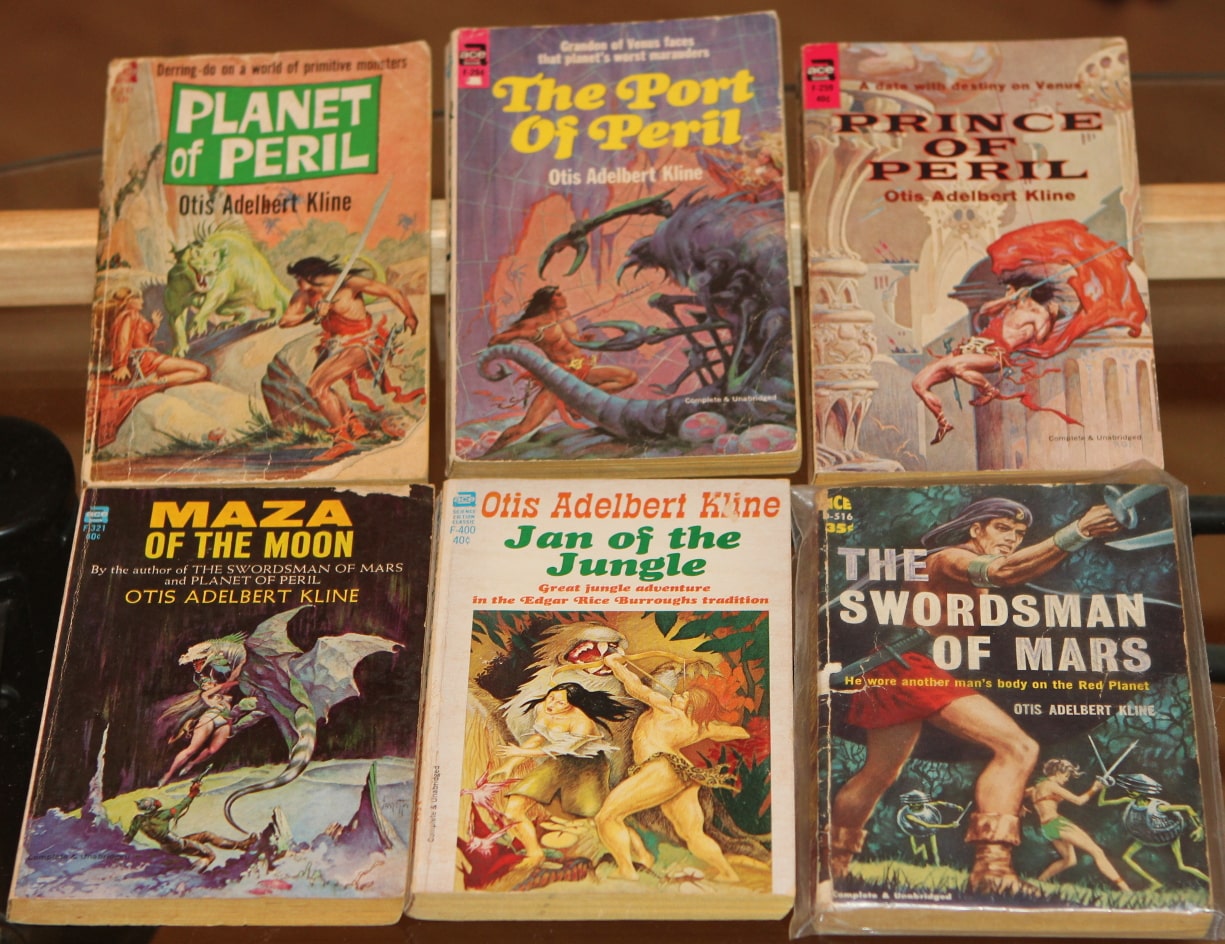

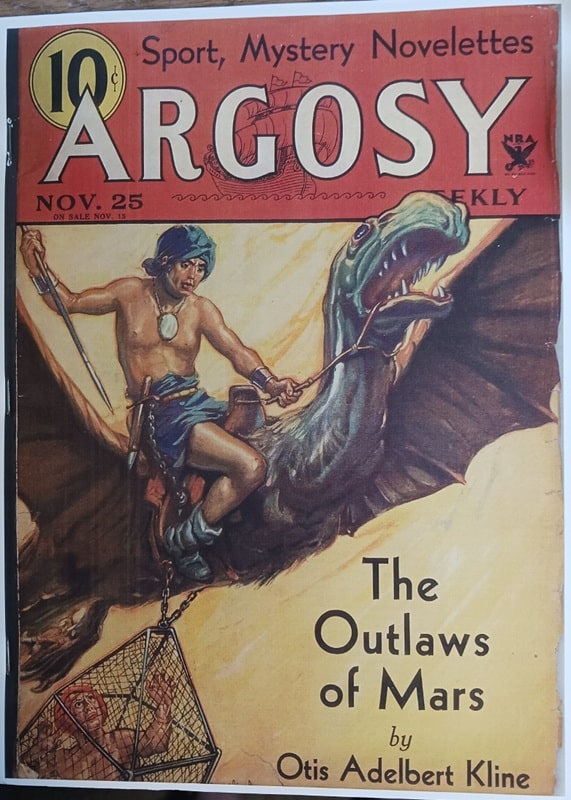

Facsimile editions of Argosy Weekly, January 7, 1933 and November 25, 1933. Covers by Robert A. Graef

Above are pictures of my facsimile copies of his two Mars books, The Swordsman of Mars and The Outlaws of Mars. These reprint the chapters from the original magazine publications with many of the illustrations.

Charles Gramlich administers The Swords & Planet League group on Facebook, where this post first appeared. His last article for Black Gate was a review of the Flashing Swords! anthology series edited by Lin Carter.

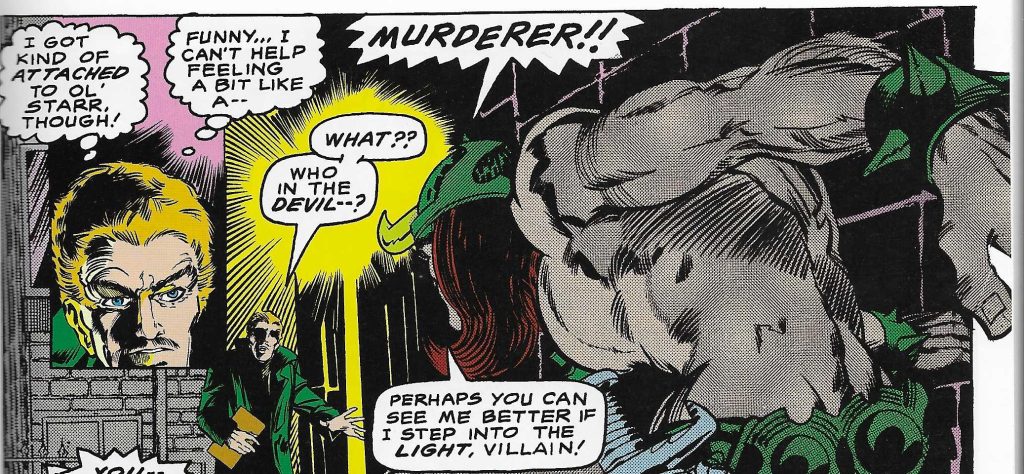

By Crom: It’s Conan…I Mean, Starr the Slayer!

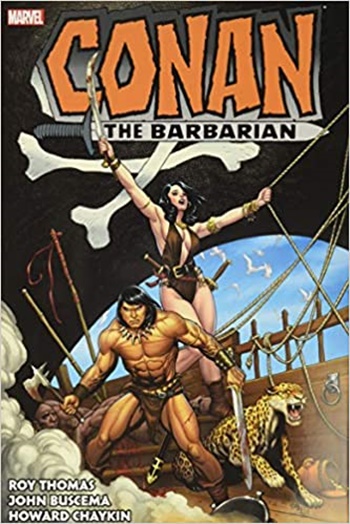

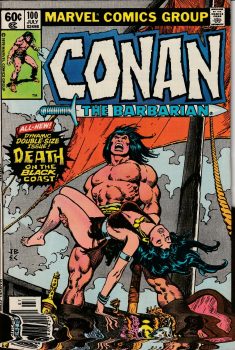

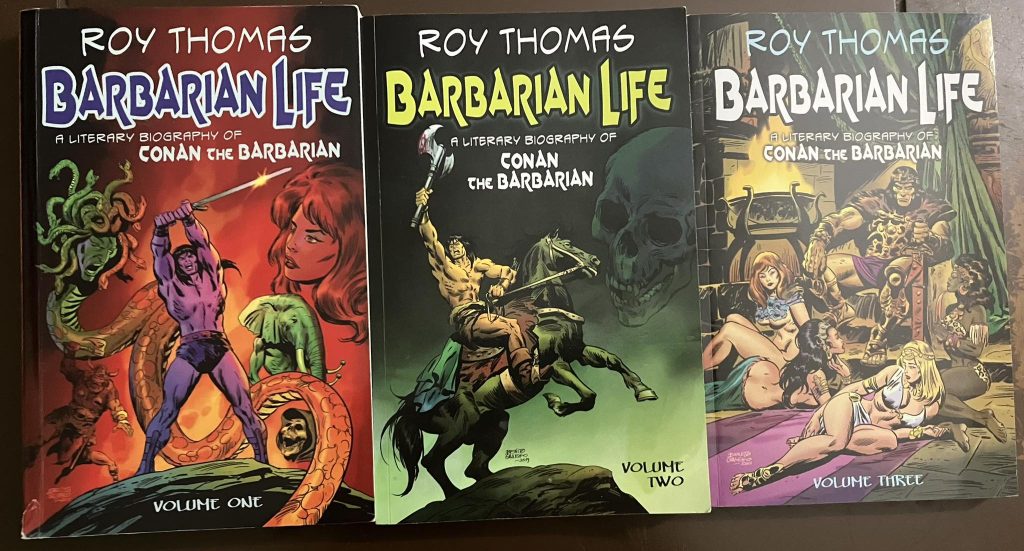

Having finished the first 100 issues of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian, I did a post last week on Roy Thomas’s memoirs and that series. Which OF COURSE you read, here.

Having finished the first 100 issues of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian, I did a post last week on Roy Thomas’s memoirs and that series. Which OF COURSE you read, here.

I started reading the first Savage Sword of Conan Omnibus from Marvel, but I’m still in a CtB mood. So, I decided to write another post about it. Sort of…

The first issue of Conan the Barbarian actually followed the sandalled feet of Starr the Slayer.

Just for fun, Roy Thomas had written a sword and sorcery story, and he had Barry (not yet ‘Windsor’) Smith draw it. Starr the Slayer was a very Conan-esque barbarian. In the story, he was the creation of Len Carson (named after Conan pastiche writer, Lin Carter), who dreamed his plots. But mentally exhausted from this, Carson wanted to kill off his meal ticket. Starr somehow travels to Carson’s time and kills the writer for attempting to dispose of him. Uh, okay, sure.

Starr appeared in the fourth issue of the Marvel anthology, Chamber of Darkness, hitting newsstands in April of 1970 (CtB debuted in October of the same year). Smith both penciled and inked the entire installment for Starr, from Thomas’ story.

Thomas did not intend for it to be an ongoing character, though it seems entirely conceivable that if Marvel had followed form and developed their own in-house character (giving them all the rights), instead of licensing one, Starr could well have been Marvel’s sword-swinger.

Smith gave Starr a distinctive medallion necklace. He also adorned the barbarian with a horned helm – except, the horns were in the front, rather than the side. This turned out to be important, because Smith and Thomas decided to keep both of those items for Conan. Marvel fans were used to superheroes in costumes. Conan got a bit of a mini-costume in this manner.

At only seven pages, it’s pretty short. Smith had been booted out of the United States green-card violations, and drew Starr while in England. He had also been doing some barbarian drawings for his own amateur magazine called Paradox. This black and white drawing by Smith might be one of them.

So, Smith had experience with drawing barbarians when Thomas approached him about Conan. Boss Goodman had put the kibosh on John Buscema by limiting the amount he would pay the illustrator. Which also knocked out fellow candidate Gil Kane (both of who would later draw much Conan). Thomas had passed on a couple Stan Lee suggestions, and then settled on Smith, who was near the bottom end of the pay scale.

So, Smith had experience with drawing barbarians when Thomas approached him about Conan. Boss Goodman had put the kibosh on John Buscema by limiting the amount he would pay the illustrator. Which also knocked out fellow candidate Gil Kane (both of who would later draw much Conan). Thomas had passed on a couple Stan Lee suggestions, and then settled on Smith, who was near the bottom end of the pay scale.

Thus, Marvel rather unintentionally did a trial run at Conan. I talked a bit about how the Conan comic book came about in last week’s post. But I do a deep dive into it in the started but nowhere completed series I have planned here at Black Gate on Thomas’ first ten issues of Conan the Barbarian. I have read the first hundred issues as prep work though. And this essay you’re reading was part of the series.

Marvel could easily have created their own in-house barbarian. And they had offered to pay Lin Carter for the use of his Conan clone, Thongor. But Carter’s agent held out for more money (apparently Martin Goodman NEVER caved on financial matters), and Thomas contacted Glenn Lord, the rights agent for Robert E. H(‘Of Aquilonia’ had come out.oward’s estate.

Lancer was essentially finished printing new Conan books (all but ‘The Buccaneer’ and ‘Of Aquilonia’ had already come out, and there was no popular Conan movie. There was no guarantee that Conan would be a hit. Thanks to those paperbacks with the Frank Frazetta covers, he was more recognizable than Thongor, or John Jakes’ Brak the Barbarian. But Conan was no sure thing as a comic.

Thankfully, Thomas convinced Stan Lee and Martin Goodman, and Conan became not only a Marvel best-seller, but is a popular franchise to this day (Marvel having re-obtained the rights a few years ago, but they are now held by Titan.

Starr did return, though not very memorably.

In 2007, Marvel included a version of Starr in its new version of the newuniversal series. I’ve never seen it, nor am I interested in the concept. You can go look it up for yourself if you want.

In 2009, Marvel’s Max Comics (adult-oriented imprint put out four new Starr the Slayer comics. All four are available digitally.

Prior Conan Comic Posts

By Crom: Marvel, Roy Thomas, and The Barbarian Life

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ made its Black Gate debut in 2018 and has returned every summer since.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017. And he irregularly posts on Rex Stout’s gargantuan detective in ‘Nero Wolfe’s Brownstone.’ He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’).

He organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series, as well as the award-winning ‘Hither Came Conan’ series. Which is now part of THE Definitive guide to Conan. He also organized 2023’s ‘Talking Tolkien.’

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories — Parts III, IV, V, VI, XXI, and XXXVII.

He has written introductions for Steeger Books, and appeared in several magazines, including Black Mask, Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine, The Strand Magazine, and Sherlock Magazine.

You can definitely ‘experience the Bobness’ at Jason Waltz’s ’24? in 42′ podcast.

Mechanical Trees and Mini-Woolly Mammoths: May-June Print Science Fiction Magazines

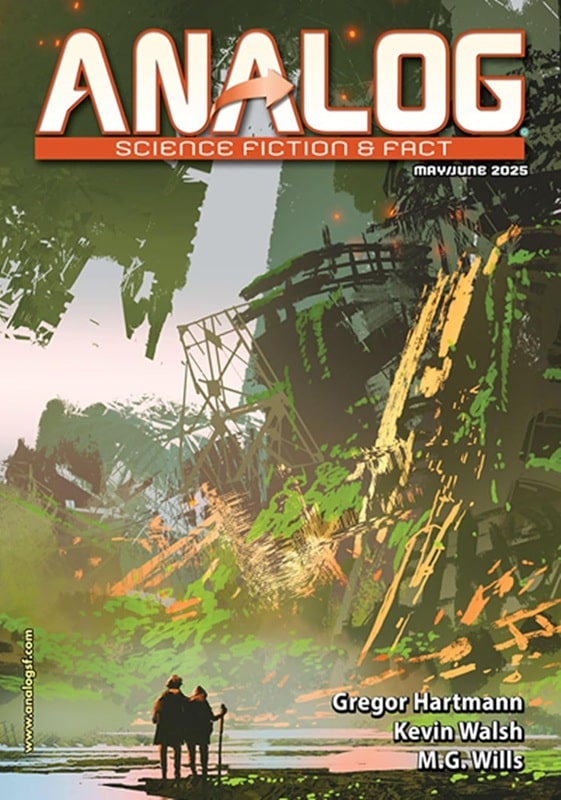

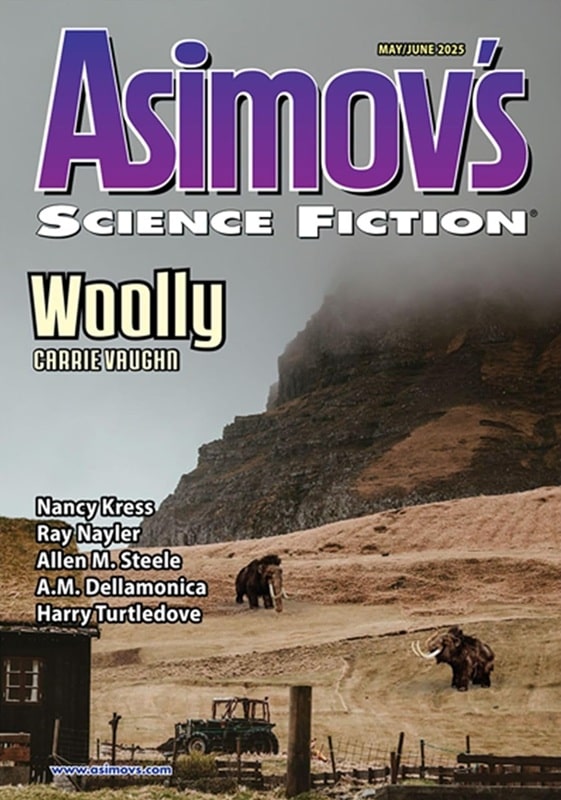

May-June 2025 issues of Analog Science Fiction & Fact and Asimov’s Science

Fiction. Cover art by Tithi Luadthong/Shutterstock, and IG Digital Arts & Annie Spratt

Back in February I was surprised to learn that the last surviving print science fiction magazines, Analog, Asimov’s Science Fiction, and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, had all been sold to Must Read Books, a new publisher backed by a small group of genre fiction fans. I was very sad to see Analog & Asimov’s leave the safe harbor of Penny Press, where they’ve both sheltered safely for very nearly three decades as the magazine publishing biz underwent upheaval after upheaval.

But I was nonetheless cautiously optimistic. The magazines couldn’t continue to survive as they were, with 25+ years of slowly declining circulation — and indeed F&SF, while it claims to be an ongoing concern, has not published a new issue in nearly a year.

But after four months, that optimism is rapidly fading. The first issues from Must Read, the May-June Analog and Asimov’s, technically on sale April 8 – June 8, have yet to appear on the shelves at any of my local bookstores, and there’s been no word at all at when we can expect the July-August issues, scheduled to go on sale today. And there’s no whisper of when we might expect to see a new issue of F&SF at all.

The March-April issues of Analog and Asimov’s SF, still on the shelves at Barnes and Noble in Geneva, Illinois on June 7, 2025

The March-April issues of Analog and Asimov’s SF, still on the shelves at Barnes and Noble in Geneva, Illinois on June 7, 2025

So why are there photos of the May-June issues at the top of this column? Are they ChatGPT hallucinations?

Nope. If you have a digital subscription, your issues of Analog and Asimov’s arrived on time on April 8. And I’m told that folks with print subscriptions received hard copies in the mail around May 15. So copies do, in fact, exist. But the new owners don’t seem to have the myriad complexities of distribution figured out yet.

A shame, since I’d love to get my hands on the latest issues (after having my copies mangled by the post office in the 80s, I switched to buying them from bookstores, and have stuck with that method for the last 40 years). They’re just as enticing as usual, with contributions from Nancy Kress, Allen M. Steele, Ray Nayler, Harry Turtledove, Steve Rasnic Tem, Carrie Vaughn, A.M. Dellamonica, Brenda Cooper, Shane Tourtellotte, Mark W. Tiedemann, Gregor Hartmann, Howard V. Hendrix, and many more.

Mina at Tangent Online enjoyed the latest Asimov’s.

“The Hunt for Lemuria 7” by Allen M. Steele is a sequel to “Lemuria 7 Is Missing” [from the July/August 2023 issue]. The story is a mosaic of various sources piecing together the efforts to find the missing crew of six like a lunar Mary/Marie Celeste. Merlin Feng is determined to find out what happened to his mentor and his mentor’s daughter and former girlfriend, Amelia. He designs robotic rovers with advanced AI systems to investigate the site of their disappearance and other sites where Transient Lunar Phenomena have been observed. Five years after the disappearance, Amelia turns up at the Great Wall of China. All she can say is that she has been sent back to warn others not to set foot on the moon…

“In the Forest of Mechanical Trees” by Steve Rasnic Tem is a thoughtful and thought-provoking story about a world living with climate change and other environmental ravages. An elderly couple run a theme park in the ever-growing Arizona desert. The park includes trees that soak up carbon dioxide and sculptures to commemorate the growing list of extinct species. The park’s staff are determined in their fight against the elements and it’s curiously not a depressing story. But it is a sobering reminder of the direction humanity is heading in.

“The Fight Goes On” by Harry Turtledove imagines a Sarajevo in 1914 filled with time travellers: some trying to stop the murder of Franz Ferdinand; some trying to ensure it happens. We follow the attempts of one time traveller. It was well-written and amusing but didn’t grab me.

In “The Tin Man’s Ghost” by Ray Nayler, we meet Sylvia Aldstatt again: the agent who can speak with the dead with the help of alien technology. We are in the McCarthy era but in a world changed by the use of technology reverse engineered from a crashed flying saucer. Sylvia’s mission this time is to talk to the ghost of a robot (also referred to as a war machine or the Tin Man by others, as a “mechanical” by itself). Sylvia discovers that all mechanicals were given the memories of one man, Alvin Greenly, but that they diverged over time. And she discovers that mechanicals are capable of courage and sacrifice. Sylvia also meets Oppenheimer but that is not the main focus of the story; the main focus is on stopping, or at least slowing down, the development of the atomic bomb. The mechanical, Bill, worms its way into our hearts, giving the last line of the story its full poignancy… an excellent novelette.

“Trial by Harry” by Michael Libling is ultimately a horror story. A new drug is on trial for older people in a vegetative state. Harry is visited faithfully by his two surviving children as he slowly comes back up from the bottom of a deep well. We see his memories as he recovers them and slowly we realise that Harry was not a good man. The title takes on a chilling double meaning as you reach the end of the story.

“Woolly” by Carrie Vaughn is a warm tale. Joy runs a rescue farm for abandoned, genetically modified, mini-woolly mammoths. When the government decides to put them all down, Joy needs to win more time to fight the decision in court. The tale ends on a light note, with the reader rooting for Joy and her charges.

Read Mina’s complete review here.

The new Analog is reviewed by the always reliable Victoria Silverwolf at Tangent Online. Here’s a sample.

“Isolate” by Tom R. Pike takes place in a galactic empire ruled by a monarch who is worshipped as a deity. The protagonist is a cleric and a linguist, sent to a remote region of a planet recently annexed to the empire. Her task is to determine if the local language is related to the empire’s official language, and thus acceptable, or if it must be eliminated…

In “The Robot and the Winding Woods” by Brenda Cooper, an elderly couple maintains a campground, even though there have been no visitors for many years. A robot arrives to tell them that the area is to be returned to pure wilderness, and that they must leave. Another fact revealed by the robot changes the situation…

“Mnemonomie” by Mark W. Tiedemann takes place in a society where boys become men by having their memories completely replaced, instantly changing them from adolescents interested in aggressive sports to adults with careers. One such young man suffers brain injury during an attack by a rival team, so the process is not completely successful, leaving him with memories of his past. In this way, he learns something about the world in which he lives…

“The Scientist’s Book of the Dead” by Gregor Hartmann takes place years after a devastating war wiped out most of humanity and a revolution resulted in a world ruled by technocrats. The western hemisphere is completely depopulated and left as a wilderness area. The aging leader of the revolution and his chief of staff, a young woman bred to be at the peak of human ability, lead the narrator and other technocrats on a hike in an otherwise deserted North America… The story offers much food for thought, without easy answers.

The two characters in “Siegfried Howls Against the Void” by Erik Johnson are sentient starships, many lightyears apart in their separate voyages. Over millennia, they send occasional messages to each other. One of them, identified as male, comes to depend on the signals from the other, identified as female. In addition to making the starships seem like people, the author also anthropomorphizes stars and planets, describing them as mothers and their children. Despite having no human characters, this is a romantic story, with interstellar exploration as a source of emotional wonder and despair… This is the author’s first published story, and it reveals a rich imagination and a lush narrative style that could benefit from a little discipline.

The novella “Bluebeard’s Womb” by M. G. Wills deals with a project to create a uterus within a man’s body, which can then have an embryo implanted in it so the man can give birth by Caesarean section. The first volunteer is an acquaintance of the woman in charge. He has his own agenda, which only becomes clear after the child is born. Although this is not the first story to feature male pregnancy, it is unusually realistic and scientifically plausible… this provocative work is sure to create controversy. Readers’ opinions on the issues raised in it will determine how they react to it.

Read Victoria’s full review here.

Here’s all the details on the latest SF print mags.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

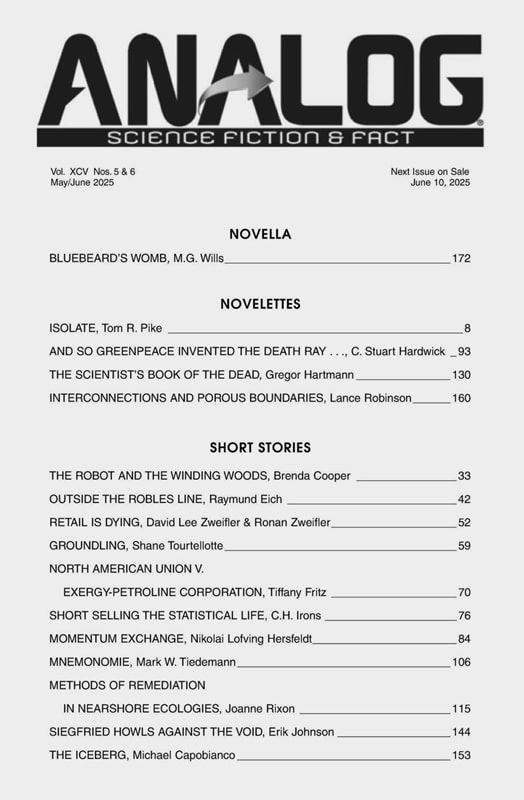

Analog Science Fiction & Science Fact, May-June 2025 contents

Editor Trevor Quachri gives us a tantalizing summary of the current issue online, as usual.

Unlike this issue, there’s no grand unifying theme for May/June other than “good stories,” but that’s okay: it’ll keep you on your toes!

First up is a bit of classic Schmidtian linguistic science fiction in “Isolate” by Tom R. Pike. We also anchor the issue with what’s likely to be the definitive hard SF take on a classic SFnal “What If . . . ?” scenario, in “Bluebeard’s Womb,” by M.G. Wills, plus a bunch of other fine fiction, including a game of cat and mouse between a jailer and his prisoner, only on a grand scale, in “Momentum Exchange,” by Nikolai Lofving Hersfeldt; an older couple trying to make it in a world that no longer has room for them in a very concrete way in “The Robot and The Winding Woods,” by Brenda Cooper, plus much, much more, from folks like C. Stuart Hardwick, Kelsey Hutton, Michael Capobianco, and Gregor Hartmann.

Here’s the full TOC.

Novella

“Bluebeard Womb” by M.G. Wills

Novelettes

“Isolate” by Tom R. Pike

“And So Greenpeace Invented the Death Ray…” by C. Stuart Hardwick

“The Scientist’s Book of the Dead” by Gregor Hartmann

“Interconnections and Porous Boundaries” by Lance Robinson

Short Stories

“The Robot and the Winding Woods” by Brenda Cooper

“Outside of the Robles Line” by Raymund Eich

“Retail is Dying” by David Lee Zweifler & Ronan Zweifler

“Groundling” by Shane Tourtellotte

“North American Union V. Exergy-Petroline Corporation” by Tiffany Fritz

“Short Selling the Statistical Life” by C.H. Irons

“Momentum Exchange” by Nikolai Lofving Hersfeldt

“Mnemonomie” by Mark W. Tiedemann

“Methods of Remediation in Nearshore Ecologies” by Joanne Rixon

“Siegfried Howls Against the Void” by Erik Johnson

“The Iceberg” by Michael Capobianco

Flash Fiction

“Amtech Deep Sea Institute Thanks You For Your Donation” by Kelsey Hutton

“The Shape of Care” by Lynne Sargent

First Contact, Already Seen” by Howard V. Hendrix

Science Fact

The Day Seems as Long as a Year, by Kevin Walsh

Poetry

“Data Corrupted” by Bruce Boston (Poetry)

“Homecoming” by Brian Hugenbruch (Poetry)

Reader’s Departments

Guest Editorial: Our Lost Earth Days by Howard V. Hendrix

The Alternative View, John G. Cramer

Guest Alternative View by Richard A. Lovett

In Times to Come

The Reference Library by Sean CW Korsgaard

Brass Tacks

Asimov’s Science Fiction, May-June 2025 contents

Asimov’s Science Fiction

Asimov’s Science Fiction, May-June 2025 contents

Asimov’s Science Fiction

Sheila Williams provides a handy summary of the latest issue of Asimov’s at the website.

We have three thrilling novellas crammed into our May/June 2025 issue! The issue opens with Allen M. Steele’s exciting and enigmatic “Hunt for Lemuria 7”! Allen takes us back to the Moon where the mysterious disappearance of Lemuria 7 and its crew becomes a conundrum. John Richard Trtek delivers an exquisitely told tale set on a far-future Earth where humans who wish to emigrate to an alien planet must first embark on “The Passage.” Nancy Kress wraps up the issue with the conclusion to her brilliant hard SF story about “Quantum Ghosts”! You won’t want to miss any of these exciting works.

A.M. Dellamonica squeezes a movie-length suspense/romcom film into a short story about “The Humming of Tamed Dragons”; Michael Libling spins a deceptive horror story about what it means to endure “Trial by Harry”; Carrie Vaughn conveys the heartfelt story of a woman’s attempt to rescue “Woolly”; Ray Nayler’s novelette tells the complex tale of a retired Sylvia Altstatt called back into service by “The Tin Man’s Ghost”; Steve Rasnic Tem invites us “In the Forest of Mechanical Trees” where an elderly group of people who maintain a sculpture park try to create a whimsical sense of normalcy for a family escaping the ravages of climate change; and Harry Turtledove’s time travel tale about frustrating and tragic historical events reveal why “The Fight Goes On.”

Robert Silverberg’s Reflections muses about “The Other Schliemann”; James Patrick Kelly’s On the Net takes some “Moonshots”; Kelly Jennings’s On Books looks at works by T. Kingfisher, Madeline Ashby, John Wiswell, Cebo Campbell, Michael Bérubé, and others; Kelly Lagor’s Thought Experiment considers “Crime and Punishment in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange”; plus we’ll have an array of poetry you’re sure to enjoy.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

Novellas

“The Hunt for Lemuria 7” by Allen M. Steele (Novella)

“Quantum Ghosts (Part II)” by Nancy Kress (Novella)

“The Passage” by John Richard Trtek (Novella)

Novelette

“The Fight Goes On” by Harry Turtledove (Novelette)

“The Tin Man’s Ghost” by Ray Nayler (Novelette)

“Trial by Harry” by Michael Libling (Novelette)

Short Stories

“In the Forest of Mechanical Trees” by Steve Rasnic Tem (Short story)

“The Humming of Tamed Dragons” by A.M. Dellamonica (Short story)

“Woolly” by Carrie Vaughn (Short story)

Poetry

“Baggus Plasticus” by Ciarán Parkes (Poetry)

“Introducing My Friends to My Dad” by Chiwenite Onyekwelu (Poetry)

“Stellarium” by Stuart Greenhouse (Poetry)

“Micro Circuit” by Sai Liuko (Poetry)

“Train” by David Rogers (Poetry)

Departments

Guest Editorial: The Writes of Spring by Rick Wilber

Reflections: The Other Schliemann by Robert Silverberg

On the Net: Moonshots by James Patrick Kelly

Thought Experiment: Crime and Punishment in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange by Kelly Lagor

On Books by Kelly Jennings

Next Issue

Analog, Asimov’s Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction are available wherever magazines are sold, and at various online outlets. Buy single issues and subscriptions at the links below.

Asimov’s Science Fiction (208 pages, $8.99 per issue, one year sub $47.97 in the US) — edited by Sheila Williams

Analog Science Fiction and Fact (208 pages, $8.99 per issue, one year sub $47.97 in the US) — edited by Trevor Quachri

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (256 pages, $10.99 per issue, one year sub $65.94 in the US) — edited by Sheree Renée Thomas

The May-June issues of Asimov’s and Analog are officially on sale until June 8, but (assuming they ever show up at all) likely will be on shelves a little longer than that. See our coverage of the March-April issues here, and all our recent magazine coverage here.

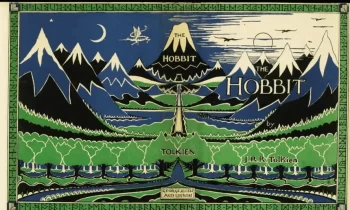

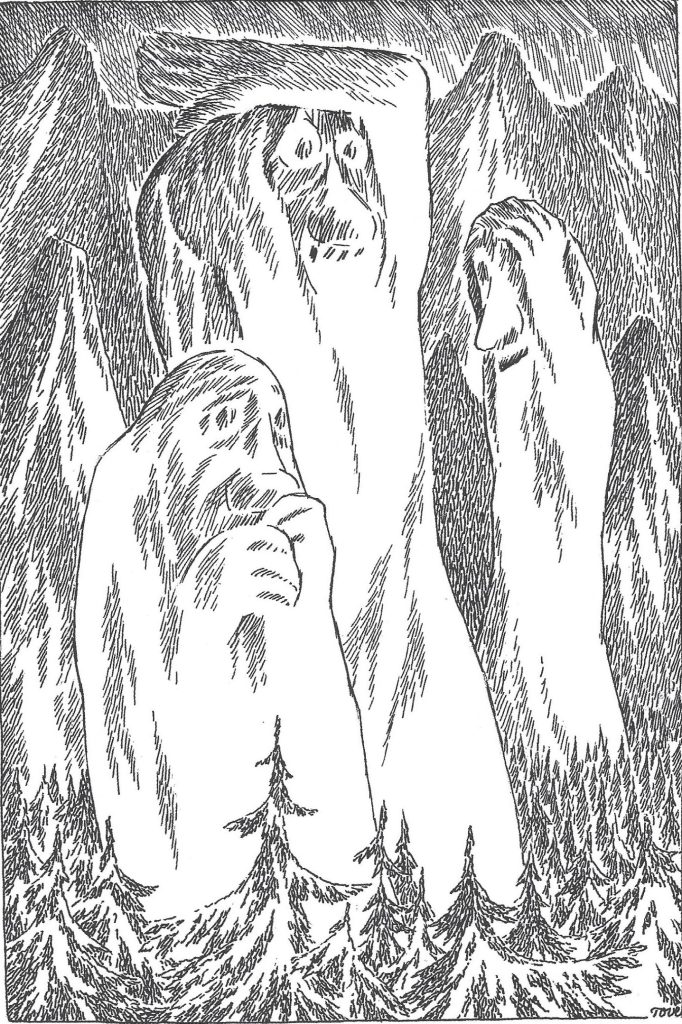

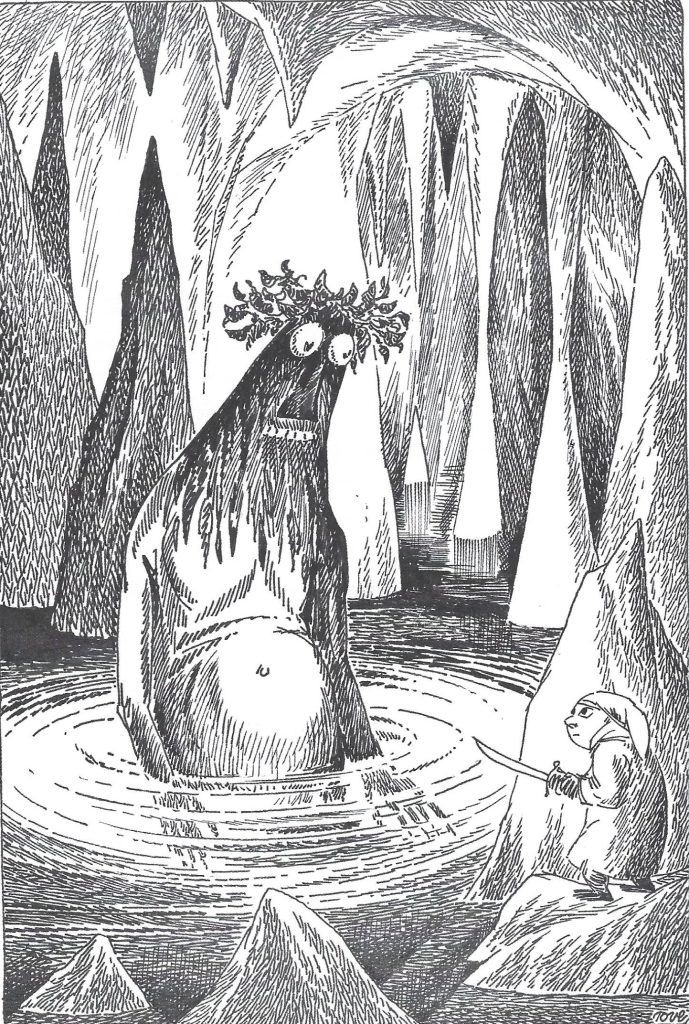

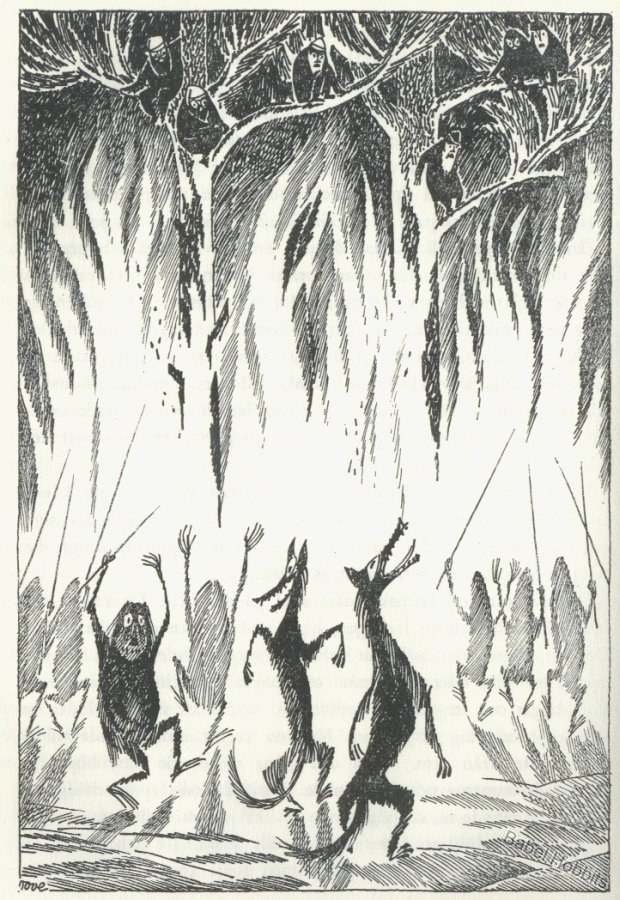

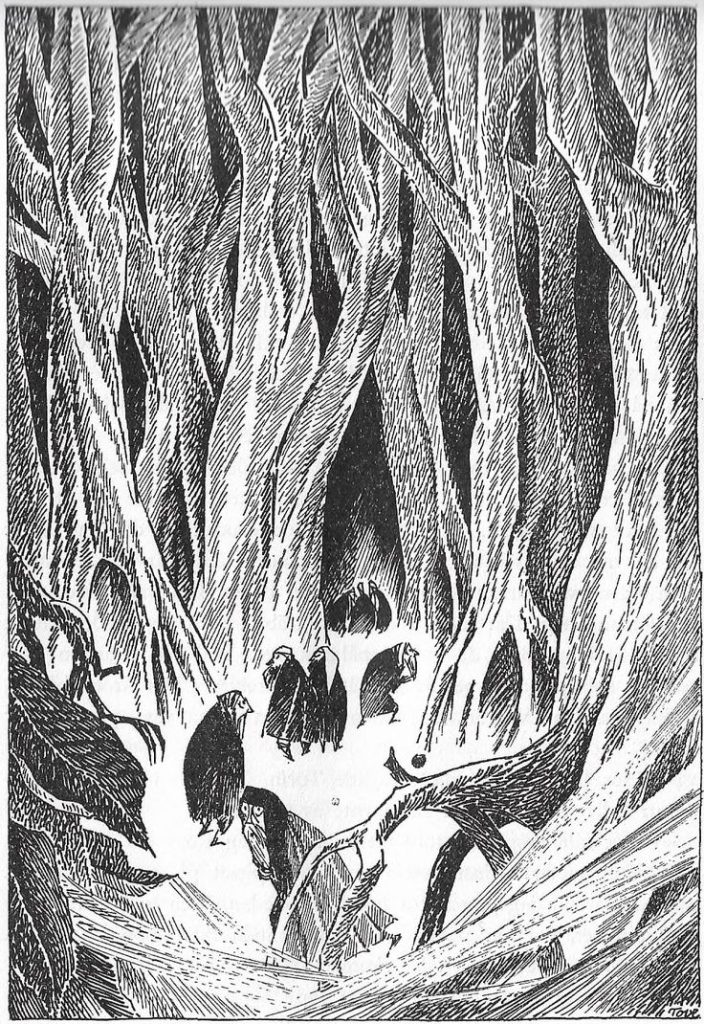

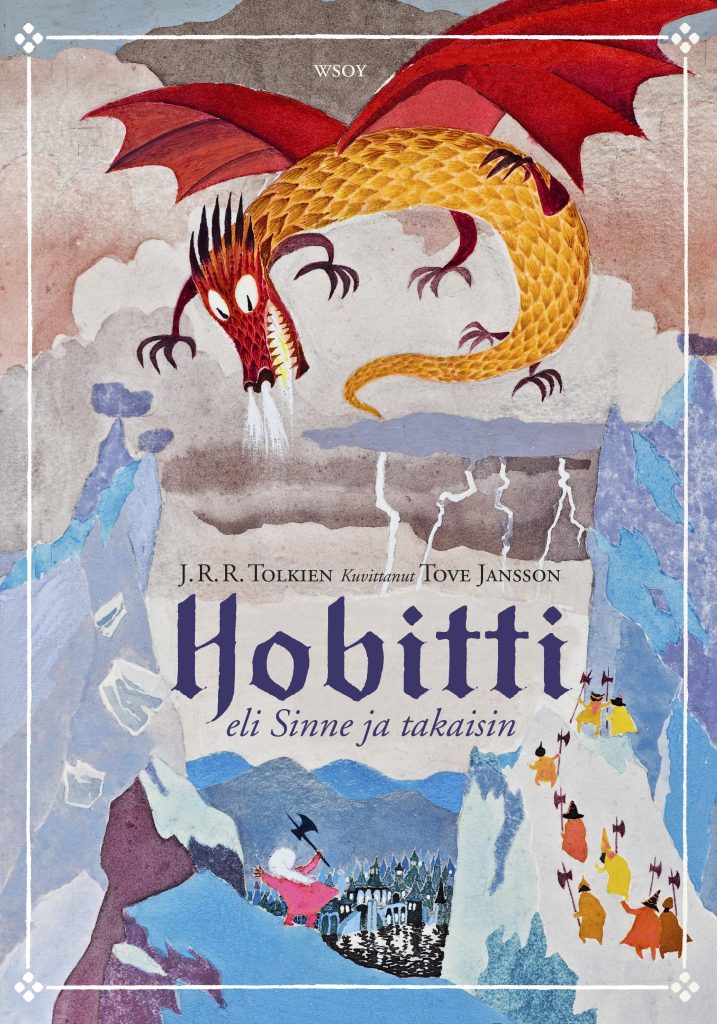

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Five: From the Beginning — The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

Chapter 1, An Unexpected Party – The Hobbit

Fifty years ago, when I first read this book, I didn’t imagine I’d still be reading it so many years later. Heck, I doubt I could have even imagined being as old as I am now. But I do reread it every few years. When I revisit The Hobbit, my journey is bathed in nostalgia as much as with the simple enjoyment caused by reading a charming book that I happen to know inside out, from the opening line above on through to the very end.

In my initial article on half a century of reading Tolkien back in January, I described my dad trying to get our first color tv in time to watch the Rankin & Bass The Hobbit. Remembering that again last week left me thinking more of my dad, now gone nearly 24 years, than the book. He was ten years younger than I am now when the movie first aired, which makes me feel incredibly old at the moment. For such a conservative man, he was excited to see it — admittedly, in a restrained way. I think we liked it well enough, but leaving out Beorn irked us both. Beyond Tolkien’s books, our fantasy tastes rarely coincided (I’ve got a shelf full of David Eddings books he bought, if anyone’s interested), but with The Hobbit and LOTR, we were in complete agreement.

What’s there to say about The Hobbit here on Black Gate? Nothing, really. I imagine most visitors here have read it, many more than once, and have their own ideas on it. It’s one of the most widely read books in the world. Instead, I’m going to discuss some adaptations of the book. But first, a summary.

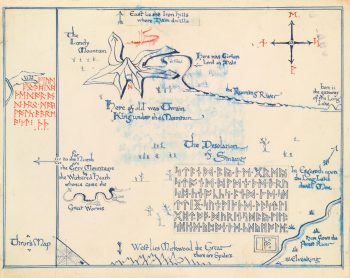

Map of the Lonely Mountain by JRR Tolkien

Map of the Lonely Mountain by JRR Tolkien

Hobbits are Tolkien’s slightly comical take on the staid British country folk. Their homeland is so British in nature, it’s even called the Shire. They prefer comfort and predictability and tend toward stoutness. Bilbo Baggins, the only son of wealthy parents has settled into a very predictable and very comfortable middle-age. When Gandalf, a wizard known fondly for magnificent fireworks and less fondly for occasionally leading young hobbits off on some adventure, appears at his doorstep, Bilbo’s life takes a drastic turn. The wizard has come to bring Bilbo on an adventure. Despite the hobbit’s denial of any interest in such an undertaking, Gandalf leaves a mark on his door so a throng of dwarves can find their way their the next day.

The dwarves, led by Thorin Oakenshield, are survivors of the Lonely Mountain. Once a mighty and wealthy dwarven stronghold, one hundred and seventy one years earlier, it was sacked by the great dragon Smaug and its citizens killed or driven out. Save Thorin and one other, the dwarves are miners and smiths, not fighters. Still, the band is determined to reclaim their mountain and their treasure, despite having neither a plan nor the means to remove the dragon.

Succumbing to a repressed ancestral taste for adventure, Bilbo joins the dwarven company on its quest. Soon, Bilbo finds himself on the wrong side of hungry trolls, angry goblins, and, perhaps worst of all, Gollum.

Deep down here by the dark water lived old Gollum, a small slimy creature. I don’t know where he came from, nor who or what he was. He was Gollum—as dark as darkness, except for two big round pale eyes in his thin face. He had a little boat, and he rowed about quite quietly on the lake; for lake it was, wide and deep and deadly cold. He paddled it with large feet dangling over the side, but never a ripple did he make. Not he. He was looking out of his pale lamp-like eyes for blind fish, which he grabbed with his long fingers as quick as thinking. He liked meat too. Goblin he thought good, when he could get it; but he took care they never found him out. He just throttled them from behind, if they ever came down alone anywhere near the edge of the water, while he was prowling about. They very seldom did, for they had a feeling that something unpleasant was lurking down there, down at the very roots of the mountain. They had come on the lake, when they were tunnelling down long ago, and they found they could go no further; so there their road ended in that direction, and there was no reason to go that way—unless the Great Goblin sent them. Sometimes he took a fancy for fish from the lake, and sometimes neither goblin nor fish came back.

Just prior to his encounter with Gollum, Bilbo finds a plain golden ring, a Ring that will come to prove of vital importance in later years. After discovering it turns its wearer invisible, Bilbo uses it to his advantage to escape from the goblins, and to save the dwarves on several occasions, once from giant spiders and once from elven prison cells. Eventually, he even uses it to allow himself to engage in some dangerous banter with the dragon.

“Well, thief! I smell you and I feel your air. I hear your breath. Come along! Help yourself again, there is plenty and to spare!”

But Bilbo was not quite so unlearned in dragon-lore as all that, and if Smaug hoped to get him to come nearer so easily he was disappointed. “No thank you, O Smaug the Tremendous!” he replied.

“I did not come for presents. I only wished to have a look at you and see if you were truly as great as tales say. I did not believe them.”

“Do you now?” said the dragon somewhat flattered, even though he did not believe a word of it.

“Truly songs and tales fall utterly short of the reality, O Smaug the Chiefest and Greatest of Calamities,” replied Bilbo.

“You have nice manners for a thief and a liar,” said the dragon. “You seem familiar with my name, but I don’t seem to remember smelling you before. Who are you and where do you come from, may I ask?”

“You may indeed! I come from under the hill, and under the hills and over the hills my paths led. And through the air. I am he that walks unseen.”

“So I can well believe,” said Smaug, “but that is hardly your usual name.”

“I am the clue-finder, the web-cutter, the stinging fly. I was chosen for the lucky number.”

“Lovely titles!” sneered the dragon. “But lucky numbers don’t always come off.”

“I am he that buries his friends alive and drowns them and draws them alive again from the water. I came from the end of a bag, but no bag went over me.”

“These don’t sound so creditable,” scoffed Smaug. “I am the friend of bears and the guest of eagles. I am Ringwinner and Luckwearer; and I am Barrel-rider,” went on Bilbo beginning to be pleased with his riddling.

“That’s better!” said Smaug. “But don’t let your imagination run away with you!”

By hands other than their own, the dwarves find themselves rid of the dragon. This leaves them in control of the mountain and the treasure. Part of the treasure, though, is sought, not unreasonably, by the dragon’s slayer, among others. Dwarves, being dwarves — “dwarves are not heroes, but calculating folk with a great idea of the value of money” — have no intention of giving up one farthing of their hoard, and soon the stage is set for a great battle. Bilbo makes it home, but only after having to commit an act of great moral bravery. The hobbit who returns home is not the same as the one who left, which of course, will turn out to be of the greatest importance for Middle-earth in the years to come.

The first and best adaptation I’m familiar with is the audio version performed by Nicol Williamson for Argo Records in 1974. Lasting nearly four hours, it has the room to tell most of the story. I remember my mother bringing it home from the library and realizing how long and complete it was. I listened to all of it on a Saturday and loved every minute of it.

Williamson himself did many of the edits, removing the most of the ‘he saids.’ He used various regional UK accents to differentiate the various characters. Williamson was one of the great stage actors of the last century, possessed of an absolutely magnificent and captivating voice. I haven’t listened to all of Andy Serkis’ unabridged presentation of the book, but as good as what I’ve heard is, Williamson’s is still the winner. Here’s Part Two of Williamson’s version, starting with Bilbo’s encounter with a wonderfully ghastly sounding Gollum.

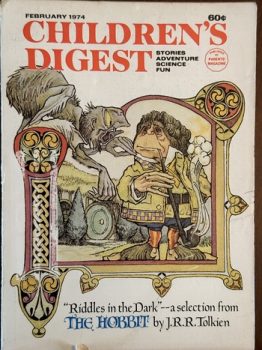

The video clip above of Bilbo and Smaug in the summary is from the second adaptation, the 1977 Rankin and Bass animated The Hobbit. The character designs were by Lester Abrams who had illustrated the Bilbo-Gollum confrontation for Children’s Digest. Arthur Rankin had seent he illustrations and liked them enough to engage Abrams for the movie. The animation was done by the Japanese company Topcraft (which would later go on to do Miyazaki’s first movie, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and become part of the foundation of Studio Ghibli).

The video clip above of Bilbo and Smaug in the summary is from the second adaptation, the 1977 Rankin and Bass animated The Hobbit. The character designs were by Lester Abrams who had illustrated the Bilbo-Gollum confrontation for Children’s Digest. Arthur Rankin had seent he illustrations and liked them enough to engage Abrams for the movie. The animation was done by the Japanese company Topcraft (which would later go on to do Miyazaki’s first movie, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and become part of the foundation of Studio Ghibli).

I love the movie, despite its too-rapid pace, the elimination of Beorn, and overall simplification. The painted scenery and backgrounds are wonderful, presenting Middle-earth in warm, muted colors. It looks at once realistic and fantastic. The voice acting, if not of Williamson’s caliber, is first-class, with Orson Bean as Bilbo, John Huston as Gandalf, Hans Conreid as Thorin, and, most wonderfully, Brother Theodore as Gollum.

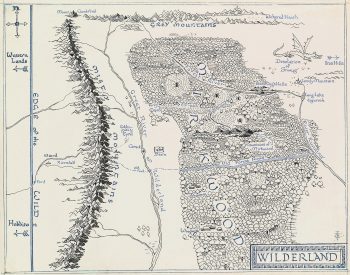

Map of Wilderland by JRR Tolkien

Map of Wilderland by JRR Tolkien

It’s far from perfect, but it succeeds better than anything else at conveying a sense of real wonder with each new encounter Bilbo has with the increasingly strange and dangerous denizens of the Wilderlands east of the Shire. Rankin had declared that there would be nothing in the movie that wasn’t in the book, and he proved largely true to his word. It also makes good use of Tolkien’s songs. I admit to not loving Tolkien’s songs and poetry in The Lord of the Rings, but in The Hobbit, he provides some solid children’s poetry and it carries over well in the film. That it remains a children’s film and not some tarted up action movie is its greatest strength. Bilbo is a likeable and brave, and the scary bits are just scary enough for young viewers. At 78 minutes, it’s also the perfect length to get exposed to Middle-earth and JRR Tolkien.

I haven’t much to say about Peter Jackson’s three, interminable, cacophonous movies save “I give up!” I feel like I watched them for penance for any and all sins I’ve ever committed and will yet commit. Martin Freeman is fine enough, if far too thin, as Bilbo, but everything else is awful. Instead of the episodic charm of JRR Tolkien’s actual book, Jackson delivered three movies totaling nearly eight hours of sodden, CGI-infested stuff, packed full of things JRR Tolkien could never have conceived of.