Feed aggregator

Goth Chick News: Hitting the Show Circuit Hard in 2025

This is why BLACK GATE gives out press passes

This is why BLACK GATE gives out press passes

And so this happened last week…

John O (the big cheese): People probably imagined you lot (Photog Chris Z and I presumably) are just hunkered down there in the subterranean offices of Black Gate sequestered with a blender, several bottles of adult beverages and the Roku horror channels.

Me: So…?

John O: So – that’s not the image we want to portray here at Black Gate.

Me: We have an image?

John O: OF COURSE WE HAVE AN IMAGE! Why can’t you be more like Bob Byrne?

Me: Bob? Oh… you mean Sherlock. Right. Wait, what was that first thing again?

John O: [insert unpublishable adult language] Would you please just go be visible somewhere? Be a reporter – get out in the field and report. That’s what Bob does. He reports… on detectives… for Black Gate.

Me: The ice machine is broken again.

John O: ARG! [insert more adult language and stomping up the stairs]

What John O doesn’t know but what — and I’m just guessing here — he wants to know, is the following.

About the time “the season” has officially concluded for Goth Chick News (and the season runs from March through November), we have a short holiday break before plunging headfirst into a new annual show circuit: hell bent on bringing you the warmest, moistest, gooiest news from the underside of pop culture.

This year the 2025 circuit kicks off with the Halloween & Attractions Show, followed by Days of the Dead’s first trip through Chicago. From that point forward it’s all go here at Goth Chick News, with a couple of new events thrown in this year.

The Halloween & Attractions Show: Feb 27-Mar 2 (Industry only)

Days of the Dead Convention Chicago: Mar 28-30

Chicago Comic and Entertainment Expo (C2E2): April 11-13

Nightmare Weekend: May 2-4

The Midwest Haunter’s Convention: June 6- 8

American Hauntings Conference: June 26-29

Fan Expo: Aug 15-17

Days of the Dead Convention Chicago: November TBD

So photog Chris Z and I do get out of the office. Okay, it is mostly at night and mostly with people carrying around body parts and stuff, but that shouldn’t matter.

We can’t all be Bob.

The Masters of Narrative Drive

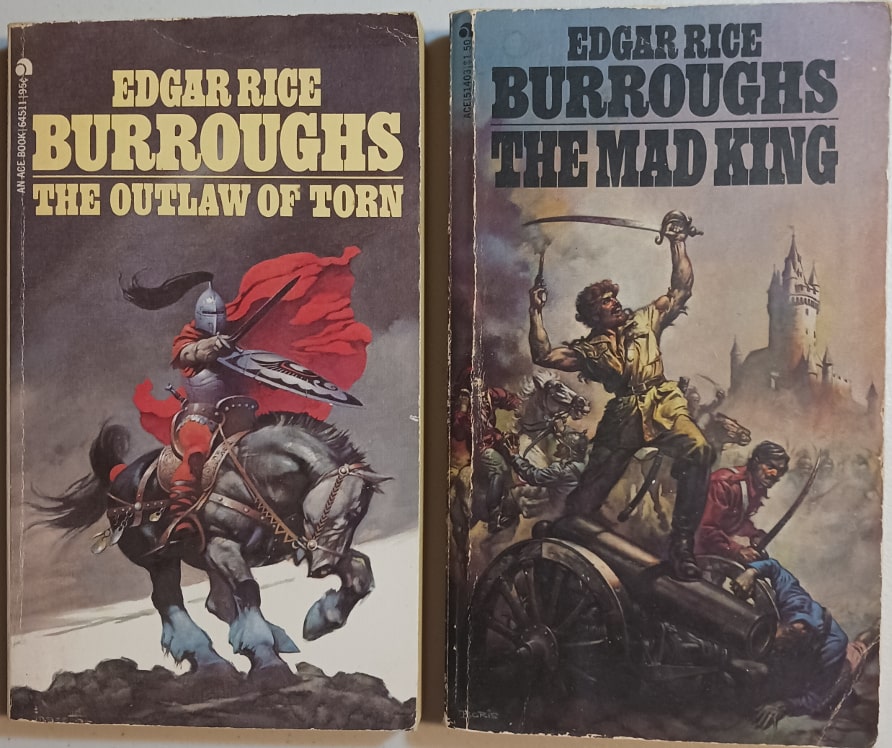

The Outlaw of Torn and The Mad King by Edgar Rice Burroughs (Ace Books, January 1973 and February 1979). Covers by Frank Frazetta and Boris Vallejo

The Outlaw of Torn and The Mad King by Edgar Rice Burroughs (Ace Books, January 1973 and February 1979). Covers by Frank Frazetta and Boris Vallejo

An author friend of 70+ books told me that a novel is just “one damned thing after another.” This is a layman’s way of saying that a book needs “narrative drive.” Narrative drive keeps readers turning the pages. It exerts a pull that drags the reader along. Edgar Rice Burroughs was the master of narrative drive. Things are happening on every page of his books that keep you wanting to know more.

There are two primary kinds of “wanting to know more.” One is, more information about the story’s plot. This is based on intellectual curiosity, and mystery stories illustrate this most clearly. Who committed the murder? Why? How? Etc. This is the primary type of drive that good nonfiction has.

The second kind of “wanting to know more” is based on emotion and character. What is going to happen to a particular character or characters the reader is attached to? The strongest narrative drive combines these.

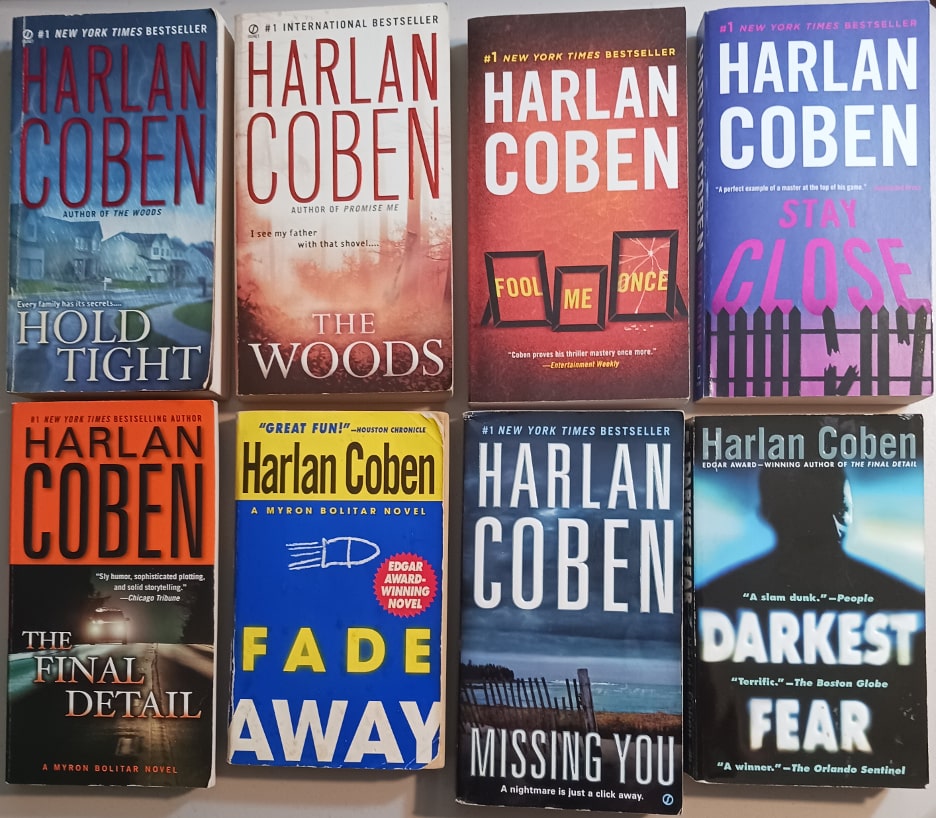

The Novels of Harlan Coben, a master of Narrative Drive

The Novels of Harlan Coben, a master of Narrative Drive

A modern author who captures both qualities — in my opinion — is Harlan Coben. Coben sets up a mystery early. Say, a character’s young brother or sister disappeared many years ago and is believed dead. But now something happens that suggests they may still be alive. This engages intellectual curiosity? How could that be? What happened to them? Where have they been?

As the story goes on, however, Coben works to get you to care about the main characters, to feel their pain. And now you want the mystery to be solved for their sake too.

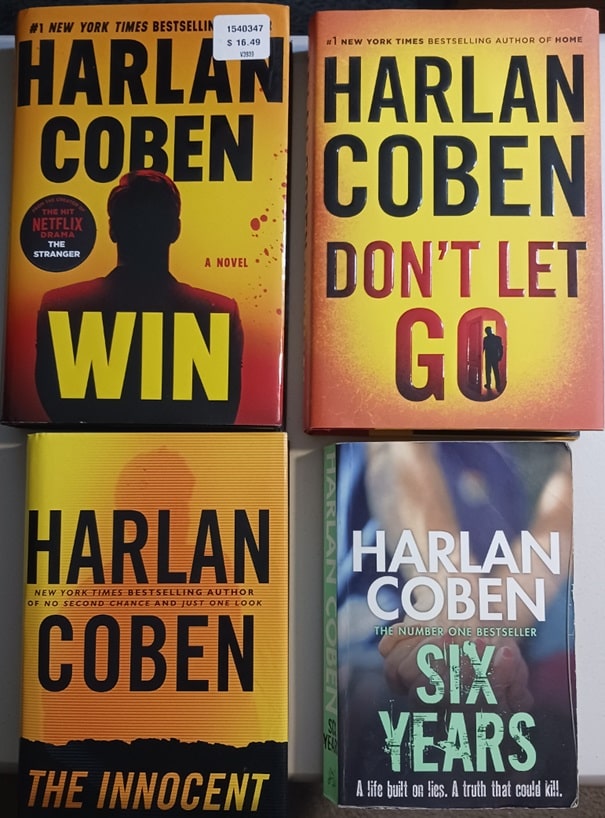

More books by Harlan Coben

More books by Harlan Coben

Such authors as Edgar Rice Burroughs and Robert E. Howard were generally able to create both types of narrative drive in their stories as well. As a young man reading about John Carter or Conan, I identified with these characters. I pictured myself in their shoes so whatever happened to them evoked emotions — fear, anger, desire, joy, melancholy. I wanted them to be successful in the story because I wanted to be successful myself.

At the same time, when these characters discovered a lost city, I wanted to know who’d built it? And why? Were any of them still around? What kind of dangers lurked in the ruins?

At age sixty-five, I find it less easy to identify with characters like Carter and Conan. They’re so different from me. I’m no sword slinging hero. Often, these days, I find myself very interested in the supporting characters, like “Sola,” the female green Martian from A Princess of Mars, or “Woola,” who becomes John Carter’s loyal animal companion.

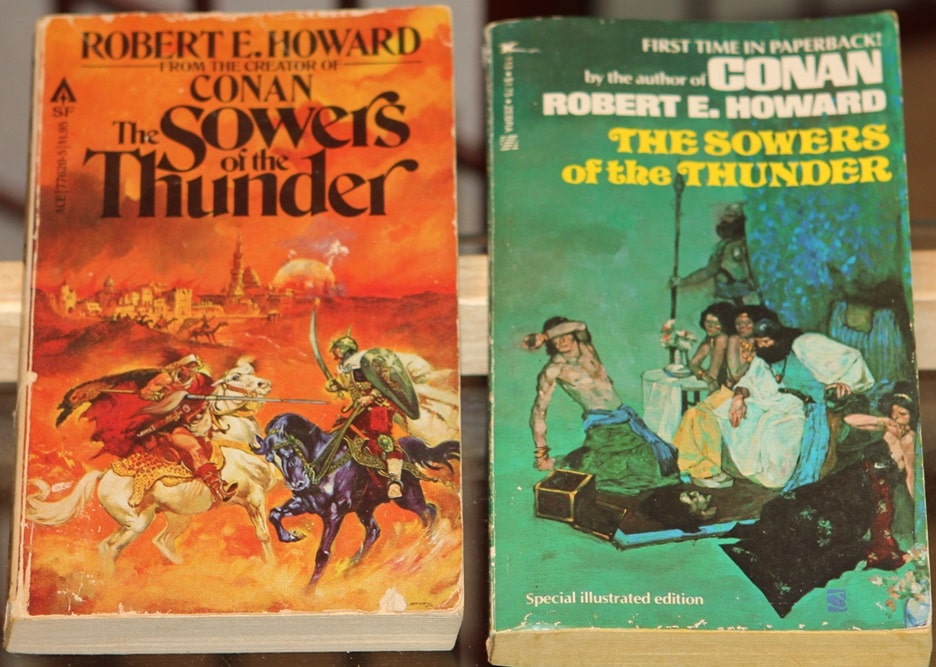

Two editions of The Sowers of the Thunder by Robert E. Howard (Ace Books, July 1979 and Zebra Books, March 1975). Covers by Esteban Maroto and Jeff Jones

Two editions of The Sowers of the Thunder by Robert E. Howard (Ace Books, July 1979 and Zebra Books, March 1975). Covers by Esteban Maroto and Jeff Jones

But I’ve never lost my intellectual curiosity about lost cities and lost worlds. Maybe I’m grown up, but there’s still a lot of “boy” in me, and good Sword & Planet fiction sure entertains that boy.

Above are some books filled with narrative drive, a few of the many Harlan Coben books I’ve read, Outlaw of Torn and The Mad King by ERB, with covers by Frazetta and Boris respectively, and my favorite REH collection, The Sowers of the Thunder, a collection of his crusader stories. Both are full of Roy Krenkel illustrations but the green cover is by Jeff Jones and the orange cover by Esteban Moroto.

Charles Gramlich administers The Swords & Planet League group on Facebook, where this post first appeared. His last article for Black Gate was a look at William R. Forstchen’s The Lost Regiment.

Business Musings: Generational Change

I do most of my business writing on Patreon these days, but roughly once per month, I’ll put a post for free on this website. If you go to Patreon, you’ll find other posts like this one.

Generational ChangeThose of you who read my monthly Recommended Reading List know I love The Year’s Best Sports Writing volumes. I always feel sad when I finish reading it, but this year, I felt especially bereft. Normally, I would have started The Best American Essays or some other nonfiction book to fill that slot, but I didn’t have anything on my TBR shelf that would have fit into that mix of uplifting and difficult and well written.

So, thanks to some automated bot suggestion on Amazon, I ordered The Best American Sports Writing of The Century, edited by David Halberstam and Glenn Stout. The book is almost 25 years old (and does not have an ebook edition for obvious reasons), but I didn’t care. I figured there would be a lot of good reading in it.

What I hadn’t expected was the healthy dose of perspective that came from David Halberstam’s brilliant introduction.

Halberstam was one of the most influential writers of his generation. He died in a car accident, not ten years after writing that introduction. I suspect he had a lot more books in him that we’ve sadly been robbed of.

He wrote one of the most devastating nonfiction books on the Vietnam War, which came out while the war was still going on. In the late 1970s, he wrote a book called The Powers That Be, which examined the impact the media had on history (put a pin in that right now), and he also wrote some of the classics of sports journalism, including a book I have on my shelf called The Summer of ’49.

All of that experience came together in this long introduction, which you can probably read as part of the “look inside this book” feature on any online bookstore.

What this introduction did was look at the history of sports journalism and sports writing as it developed in the 20th century. In the 19th, sport itself was local and often based in neighborhoods. It took nearly 100 years to become the big entertainment business it was in the 1960s, and another sixty years to become the juggernaut it is today—not that Halberstam lived to see that.

Right now, sport is getting me through some of the world’s dark times, and I noticed as it’s been happening that I had the same experience in 2020.

In the introduction, Halberstam explores several things and does so in the context of 800 pages of historical sports writing. Some of what he does here is what I call “editorial justification.” It’s something that all of us who edit do: Here are the reasons I chose the works in this book—not just because I like them (which I do) but because they make this point or illustrate that concept or explore these tiny corners of this particular topic.

Inside Halberstam’s justification, though, is a brilliant century-eye view of the way writing and journalism and entertainment changed as the world changed.

Reading about those changes got me thinking about our changing world. I’m going to get to modern times later in this post—and yes, I’ll be dealing mostly with fiction—but I’m going to set it up first.

Halberstam started the essay (and the book) with Gay Talese’s 1966 piece on baseball legend Joe DiMaggio (whom most of you probably know of because he married Marilyn Monroe). The Talese article, titled “The Silent Season of a Hero,” is considered by some to be the beginning of a sea-change in reporting called New Journalism.

In his editorial justification, Halberstam wrote:

It strikes me that the Talese piece represents a number of things that were taking place in American journalism at the time—some twenty years after the end of World War II. The first thing is that the level of education was going up significantly, both among writers and among readers. That mandated better, more concise writing.

Right there, I perked up when I was reading. It was kind of a well-duh moment for me: Of course what was happening in the journalism profession and in the craft itself was a reflection of what was going on in society at the time. Of course.

He went on:

It also meant that because of a burgeoning and growing paperback market, the economics of the profession were getting better: self-employed writers were doing better financially and could take more time to stake out a piece. In the previous era, a freelance writer had to scrounge harder to make a living, fighting constantly against the limits of time, more often than not writing pieces he or she did not particularly want to write in order to subsidize the pieces the writer did want to do.

Those changes—writers doing better financially—pretty much describes what happened to the fiction-writing profession as well, from about 1960 with the rise of paperbacks to the massive distribution collapse in the mid-1990s.

After that collapse, everything got very hard for fiction writers for about 15 years. A lot of writers vanished during that time, heading off to professorships or corporate jobs, convinced that writers couldn’t make a living at their chosen profession.

They had a point.

Anyway, a few pages later, Halberstam writes that he did not intend this collection to become a work of history, although it had “a certain historical legitimacy.” He explains:

In the background as we track the century from beginning to end, the reader should be able to see the changes being wrought by society by a number of forces: racial change, the coming of stunning new material affluence, the growing importance of sports in what is increasingly an entertainment age, and finally the effect of other communications on print.

He elaborates on all of those things, but I’m going to focus on the final one. For that, he wrote:

The role of print was changing—it was no longer the fastest or the most important means of communication. Instead by the late fifties reporters had to assume that in most cases their readers knew the [sports] score and the essentials of what had taken place; increasingly their job was to explain what happened and why it had happened, and what these athletes whom they had seen play were really like.

My copy of the book is a sea of underlines here. I really paid attention on two levels—on what Halberstam was actually saying and how all of this analysis could apply to 2025. (Not literally—again, I’ll get to it. Bear with me.)

He discussed politics and regular news reporting as seen through the lens of television cameras, and then wrote that TV had become more powerful in the 1960s than it had ever been before. He wrote:

That meant talented print journalists, to remain viable and be of value, had to go where television cameras could not go (or where television executives were too lazy to send them) and answer questions that were posed by what readers had already seen on television.

Therefore, for print to survive, the reporting had to be better and more thoughtful, the writing had to be better, and above all—the storytelling itself had to be better. Print people were being forced to become not merely journalists, but in the best sense it seems to me, dramatists as well.

I pulled back here and thought long and hard about what he was saying, and the implications.

Of course, I went to modern media first because I have three levels of training. Level one: my B.A. is in history (and I constantly wonder if I should get some graduate degrees in it—until I remember that I would have to focus on a time period and immerse myself in it. My butterfly brain resists that on so many levels that I can’t begin to express how I would feel about it).

Level two: my secondary training is in journalism. I started in print (and initially got published, ironically enough, as a sports writer at 16, covering my high school), and then fell into broadcast journalism. And no, I don’t have a degree in it. I worked as a reporter all through college, and then became a news director. Let’s put a pin in that one too.

Level three: fiction and editing. Once again, I learned by doing, which was pretty much all we had. Sure, there were classes at the universities (one story per semester, taught by someone who had no idea how to make a living at it), but mostly there were workshops (like Clarion) taught by working writers, and talks at fiction conventions and little else.

So…all of those levels combined into the way my brain worked after going deep into the Halberstam piece.

First, modern media.

I’ve been saying for some years now that it needed to change. If it’s broadcast, it’s being run by people who have no journalism experience as well as no courage. Let me add this: It has always been so. TV and radio were generally owned by entertainment companies that were required, by law, to include news.

(Most of these laws, by the way, were gutted first by the Reagan administration and then by each Republican administration since.)

The influential print media left the hands of large family groups (the Grahams at The Washington Post and the Chandlers at the Los Angeles Times come to mind), and were purchased by billionaires. At first, those purchases were praised, but they’re not going well now.

Again, this is not a huge change. William Randolph Hearst owned the biggest media empire in the world in his lifetime, and controlled content with an iron fist.

So the idea that journalism always had free reign was and is wrong.

However, when I say that the media has to change, I’m referring to generational change, just like Halberstam discussed above.

Sadly, education isn’t as good now as it was in the 1960s. The U.S. government turned its back on good education for all in the 1980s—once again under Reagan—but most successive administrations did little to shore it up. A lot of people fell through the cracks.

And now, most folks do not have the time for long-form journalism or explanations of “what happened and why it had happened.” There are/were entire cable news channels dedicated to just that kind of musing, but those aren’t reaching the younger generations either. Cord-cutting and fragmentation is actually bringing journalism into a completely different place than it was when Gay Talese wrote his article in 1966.

In some ways, we’re returning to the 19th century when the news (and entertainment) was fragmented. In other ways, we’re in a whole new place where a journalist or a fiction writer can hang out her shingle and people can come support her and her long-form journalism or fiction or whatever.

That’s good, if you’re good at the social media side, and difficult if you’re not.

But…what I mean when I say that the media needs to change with the world is that with online access and cable and broadcast news and podcasts, there are literally thousands of ways to get information.

Now, journalists need to figure out how to do it on their own. And they need to throw out some of the rules developed at the journalism schools they all went to.

Here we’re going to have a sidebar for one of my pet rants:

When I moved to Oregon, I wanted to freelance for the local Eugene paper. The city desk editor, whom they shuttled me off to, wouldn’t give me the time of day. I had written for major publications around the world. I’d had pieces on NPR and was still working for several information-based foundations. I had been a news director for years.

What I didn’t have, and what he sniffed over, was a journalism degree. My experience counted for nothing; all that mattered to him—and his cronies as the years went on—was the vaunted degree.

Over the years, I’ve worked with people who have J-school degrees but little experience. They’re terrible reporters and even worse writers. Plus they have a two-sides attitude, particularly when it comes to politics.

They don’t want to talk to everyone. They figure there’s only two sides—for and against. Most things in life are more complex than that.

So as the media landscape is fragmenting and becoming more complex, the big media companies are becoming less so.

They’re paying a price for that. But not the price everyone discussed in November. For all the hand-wringing after the election, the loss of viewership among most of the cable news channels isn’t a big deal. It happens after every election.

What is a big deal is that both readership and viewership of all traditional mainstream news has been declining for decades now. And the change is profound. People 50 and older still tend to get their news from traditional sources like television or print, but people younger than 50 get their news from social media or a digital aggregator. Mostly, though, they get their news from a variety of sources, some of them untested and inaccurate.

Rather than lament that this change allows for the spread of disinformation as most are doing, the media companies (and those of us who work in media) should be embracing the change, and finding other ways to fight disinformation.

Let me add this: when big media companies are in the hands of a single entity, be the Murdochs at Fox or Gannett News Media, the news is biased anyway. The owners of large corporations have an agenda. Sometimes it is to make profits. Sometimes it is to spread a certain perspective in the world.

Once again, it has always been thus. I didn’t work for commercial stations back in the day, because commercial reporters were muzzled. They were not allowed to report on any company that advertised with the parent company. So imagine this: no investigative reporting on pollution from a local company. Coverage was only allowed when the story became too big to ignore.

Journalism is changing again, and we need to embrace that change. We need to see the plus sides of it.

Places like Patreon and Substack help, but they have issues as well. They’re private companies that can get sold like Twitter did and then there will be huge (and often unpleasant) changes.

So…my mind went through all of that as I read the Halberstam piece. New Journalism (which is now old journalism) still exists. There are places that publish great long-form articles. Now there’s some great long-form reporting on podcasts and in new forms of media that did not exist when Halberstam wrote his introduction.

The key will be how the creatives—from writers to photographers and others—respond to these new forms of media. Some of us will adopt what we can, and others will cling to the old ways.

Maybe the old ways will return. Who knows?

Once I got through the traditional thinking on all of that, though, my mind turned toward fiction.

No one, to my knowledge, has done the kind of analysis of fiction in the 20th century that Halberstam did (first in the late 1970s, and then again in this article). Sure, there’s been a lot of writing about the history of fiction, in America in particular.

But that writing is myopic. The literary historians in the university system (including my late brother) focused on literary works or “mainstream” bestsellers, books that took over the national consciousness and led to changes and/or discussions.

There have been too many papers written on the impact of Catcher in the Rye or To Kill A Mockingbird and not enough on the overall fiction landscape.

The genres aren’t immune from the myopia. I have read as many books on the history of science fiction and fantasy as I can get my hands on, and probably just as many on the history of mystery fiction (both here and in the U.K.).

There are fewer analyses of romance fiction for two reasons: The first is that the genre is the newest of all of the big genres and second is deadlier. Romance was (and is) perceived as fiction for and by women, so it isn’t considered important (especially by the white men who ran university literary programs for most of the past century).

What books there are on romance were written by romance writers and aficionados for romance writers and aficionados.

So, let me put this out there for graduate students in search of a topic: Examine all of fiction publishing since the 1890s or so—genres, pulps, digests, and paperbacks as well as hardcovers and “important” books. See where such an examination takes you. If nothing else, I can guarantee that your dissertation will be different than all the others.

What Halberstam did so deftly in his introduction, though, is something I need to spend quite a bit of time thinking about.

He combined the changes inside America with the changes in the journalism business. Then he looked at the impact of those changes on the way that sports journalism was produced—

And he examined the impact those changes had on craft.

For example, he included little craft gems like this:

The [New York Times] in those days was still a place where copy editors were all-powerful, on red alert for any departure from the strictest adherence to traditional journalistic form, and [Talese’s] tenure there had not been a particularly happy one. But if he had wrestled constantly with the paper’s copy editors, his work was greatly admired elsewhere, particularly by reporters of his own generation in city rooms around the country who were, like him, struggling to break out of the narrow confines of traditional journalism and bring to their work both a greater sense of realism as well as a greater literary touch.

Passages like this make me think of modern traditional publishing, which got more and more hidebound after the distribution collapse in the 1990s. Then the purchase of those publishing companies by non-book people, who were buying inventory and intellectual property, and who needed these companies to make a profit on the balance sheet.

To do that, they hired editors without experience, many of them Ivy League graduates whose biggest credential was taking classes from some famous fiction writer (who could no longer make a living at writing). (Sound familiar? See J-School above.)

It became more and more difficult for established writers to work with these inexperienced (and low-wage) editors, prompting some writers to change companies. Other writers simply left to do other things, and once self-publishing became a major big deal, started publishing their own works.

There have been a lot of changes in fiction publishing, both indie and traditional, in this century. From the gold rush of new material when the Kindle was introduced in 2007 to the plethora of distribution sites for fiction, the changes have been immense.

For a while, it was possible for all of us to have the same information and act on it in the same way. If you have a newsletter, you get x-many more sales. If you monkey with Amazon’s algorithms, you will get your book in front of these eyeballs. If you use this program, you will have adequate paper books.

And then…suddenly…everything changed. Just like in the California Gold Rush, there’s money to be made in side businesses. You can make money as a cover designer, as a virtual assistant managing social media, as an expert in In-Design.

Not every writer needs those services, but a lot of them do.

What I find most amusing now is that, properly designed, indie books look better than traditionally published books. Traditional publishing companies are still trying to cost-cut their way to profit.

Indies are still experimenting with the latest bestest coolest tech, to see if it will not only enhance book sales, but also the reading experience.

What I hadn’t really considered—and I should have—was the thing that Halberstam was mentioning the most in his rather long introduction. He talked about technological, economic, and cultural change leading to changes in craft.

I know that has happened for fiction writers. I know that a lot of writers feel free to write what they want. I know many writers who are writing long series that would have either never sold at all in traditional publishing or been abandoned midway through the series.

Halberstam talks mostly about changes in storytelling methods, and I think we’re seeing that. I’m not well read enough, though, in the indie world to know what the craft changes are.

And it’s also not just a matter of being well-read. It’s also a matter of influence. When the publishing world was small, as it was in 1966, everyone saw a piece like Gay Talese’s. Everyone had an opinion about it—some good and some bad.

Talese’s influence on his peers came in the form of freedom to write differently as well as the freedom to try something new with the writing career.

We, as indie writers and publishers, can see what the something new is on the business level. I’m watching all the beautiful books being produced by writers like Anthea Sharp and Lisa Silverthorne. I want my books to be lovely as well, and I have a vision for it. Back in the day, it cost thousands of dollars to print beautiful books, and now it can be done as print-on demand.

There are other innovations that don’t interest me at all. Some of them make me ask a business question, “Should I do this? Will I be able to monetize it?” And some of them make me shrug. Some of them make me realize that there’s only so much time in every day, and I need it to do many things, including writing and running my business.

But as I climb out of these hectic and difficult past two years, I can finally see ahead. I didn’t realize, until I read the old Halberstam essay, that part of looking ahead is looking backwards on a macro scale and figuring out what the heck happened in the industry.

The cool thing about the macro scale is this: It makes everything that happened to an individual writer during the change impersonal.

For example, I got caught in the distribution downturn and wasn’t allowed by my traditional publisher to finish a series. I spent the early part of this century scrambling for work.

Then indie came along, and opened a lot of doors. But nothing remains the same. What looked good in 2015 doesn’t look good now. What worked ten years ago doesn’t work at all now.

Change happens. Sometimes it’s good, but often it’s confusing and difficult and frightening.

I was one of the first generations to go to college after New Journalism took over the big publications in New York. I had professors who railed against that. I mostly ignored it because I wasn’t a journalism major. I worked in the industry and learned a lot. But today I find myself thinking of my colleagues, many of whom were journalism majors, and wonder what they’re doing now.

I know of two people who followed the same path I did. One, a beautiful and brilliant reporter, ended up as an investigative reporter on a major Wisconsin TV station. Now, she’s working as senior anchor (and still reporting), benefitting from all the lawsuits that women had filed over the years about ageism. (She fully admits this.)

The other kept getting jobs at places that died. From UPI to major newspapers that closed up shop, he moved from place to place until he finally gave up and went fully into broadcast. I hear his familiar voice on occasion on one of the streaming channels, where he has his own show.

Those two stuck with it, weren’t afraid to take risks, and ended up with forty-year long careers.

The others…? I have no idea where they are now. I do know that, even in those halcyon days, they had trouble finding work because their writing showed their lack of experience in actual reporting.

They’re victims of a change that is no longer really relevant to modern journalism. And another change is coming.

I can see the changes in the media—as I mentioned above.

I’m going to have to think about what’s going on in fiction.

And I’m really looking forward to that.

“Generational Change,” copyright © 2024/2025 by Kristine Kathryn Rusch.

Spotlight on “These Violent Delights” by Micah Nemerever

These Violent Delights | A Literary Hub Best Book of Year • A Crime Reads…

The post Spotlight on “These Violent Delights” by Micah Nemerever appeared first on LitStack.

On McPig's Wishlist - The Farmhouse

The Farmhouseby Chelsea Conradt

The Farmhouseby Chelsea ConradtEvery woman who has lived on this farm has died. Emily just moved in.

When Emily Hauk's mother dies, it's time for her and her husband, Josh, to finally leave San Francisco. A farm in rural Nebraska is everything they want for a fresh clear skies, low costs, and distance from the grief back home.

They should have asked why the farm was for sale.

Three years ago, a teenage girl went missing from the farm. Soon after, the girl's mother mysteriously died. The deeper Emily digs, the more stories she finds of women with a connection to her new home who've met their own dark ends.

The farmhouse was meant to be Emily's fresh start, but with each passing day, her sanctuary slips further away. The barn seems to move throughout her property, as though chasing her. Her mother's favorite music drifts across the corn. She swears she saw blood in one of the farmhand's trucks. And the screams that wake her are not foxes, no matter how many times her husband says otherwise.

Despite Josh's skepticism, Emily feels the darkness that has seeped into the soil of her farm. And if she wants to claim this place as her own, she'll have to find the truth before whatever watches from the cornfield takes her too.

Expected publication June 17, 2025

Book review: The Empusium by Olga Tokarczuk

Book links: Amazon, Goodreads

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Olga Tokarczuk is the author of nine novels, three short story collections and has been translated into more than fifty languages. Her novel Flights won the 2018 International Booker Prize, in Jennifer Croft’s translation. She is the recipient of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Publisher: Riverhead Books (September 24, 2024) Length: 320 pages Formats: audiobook, ebook, hardback, paperback Translator: Antonia Lloyd-Jones

The Empusium is a strange, slow, and fascinating book. It’s part gothic horror, part social critique, and part... well, something that doesn’t really fit into any category. Call it Weirdlit, if you need to. Anyway, if you’re looking for fast-paced thrills and gruesome horrors, this isn’t it. But if you enjoy well-written and unsettling books with elegant and plastic prose* you’re in for a treat.

Tokarczuk follows Mieczysław Wojnicz, a soft-spoken, sickly man who heads to a remote spa to treat his tuberculosis. He’s surrounded by a group of other men who, between their coughing fits, like to sit around and deliver wildly outdated (and hilariously awful) opinions about women. These aren’t Tokarczuk’s inventions, by the way-they’re actual quotes from old philosophers. But don’t worry-the book knows exactly how absurd they sound and uses them to great effect.

Amid all this, there’s a creeping sense of something supernatural. Strange presences haunt the spa, hiding in the walls and floorboards, and this adds an unsettling vibe without ever taking over the story. The real horror is in the ways people treat each other, in the oppressive masculinity of the men or Mieczysław’s own struggle to live authentically in a world that doesn’t make space for him.

Speaking of Mieczysław, his journey is unexpected but well-timed and perfectly captured. I appreciated the slow process that allowed him to peel back the layers of who he is and find his true self. As mentioned, it was surprising, quite moving, and ultimately uplifting.

Yes, the pacing is slow, and yes, the philosophical ramblings won’t be everyone’s cuppa. But stick with it. The writing is beautiful; the characters are complex, and the ending? Worth the wait.

I like my books smart, spooky, and a little bit weird, and The Empusium is precisely this. Well worth a read.

A Quick Thank You…

…to all of the backers on the Series Collide Kickstarter. You went beyond our expectations. We—I—appreciate the support.

Thank you!

Recommended Reading List: August 2024

I’m still catching up on the Recommended Reading Lists for 2024. After August, I have to finish September’s (and December, of course), and then I’ll be caught up! Yay!

I remember August better than I remember July. (Whew.) We held a successful anthology workshop. We learned a lot. We made a lot of progress on truly good things. And…we had to hire a lot more lawyers than the two we usually deal with. Such fun that was/is. [sarcasm alert]

I did get a lot more reading done in August than I did in July, but still not as much as I would have liked. Although some of that reading was for the anthology workshop, which I can’t count here, but you will see many of those stories in the coming year, as we revive and rebrand Fiction River. (Oh, I’m looking forward to that.)

So you’ll find some interesting books here, and just two articles to match my necessarily short attention span from that month.

August 2024

Baxter, John, Montemarte: Paris’s Village of Art and Sin, Harper Collins, 2017. I plucked this out of my TBR pile because I needed something that was not going to challenge me in the front part of the month. I just needed vignettes, which this has in abundance. What I did not expect was how many story ideas I got from this. Quite a few! I hope I’ll have a chance to get to them before getting distracted by something else. There are a lot of fun things here, as always with a John Baxter travel “guide.” (It’s an excuse for great literary and historical essays.

Cabot, Meg, No Judgements, William Morrow, 2019. A fun and dramatic book from Meg Cabot. This one is set on a Florida island as a hurricane bears down. Our heroine is a clueless New Yorker who had never lived through severe storms before and can’t quite believe the locals when they tell her that she has to do certain things. Of course, there’s this one particular local who helps her…

One of the most fun things about this book for me is that I lived on the Oregon Coast for 23 years. We had hurricanes, although they’re not called hurricanes in that part of the world. We had Big Storms. And no one from the outside could believe that things would be bad. In fact, when there were tsunami warnings, people drove to the Oregon Coast to watch the big wave hit. Friends of ours had to yank tourists off the beaches so they wouldn’t be killed. (I kid you not.)

So there’s an extra layer in this book for me, but I think you’ll enjoy it even without that. This is Meg Cabot at her most fun.

Nevala-Lee, Alec, Astounding: John W Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, Dey Street, 2018. Alec’s book is a Hugo and Locus Award Finalist. I bought the paperback when it came out. (Note: I’ve linked to a ridiculously priced ebook.) When the book came out, I picked it up a few times, cherry-picked a few references using the index, and got grumpy. I fell into the mistake so many writers make, which is that the book I held was not the book I would have written. Let me say to me (and to all of you who do that): Well, duh. If I was going to write the book, I would…ahem…write the book.

Nevala-Lee, Alec, Astounding: John W Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, Dey Street, 2018. Alec’s book is a Hugo and Locus Award Finalist. I bought the paperback when it came out. (Note: I’ve linked to a ridiculously priced ebook.) When the book came out, I picked it up a few times, cherry-picked a few references using the index, and got grumpy. I fell into the mistake so many writers make, which is that the book I held was not the book I would have written. Let me say to me (and to all of you who do that): Well, duh. If I was going to write the book, I would…ahem…write the book.

I don’t know what made me pick up the book in August, but I’m so glad I did. It kept me entertained while a lot of the above stuff happened in my life. I had met Isaac a few times, and the bastard groped me every single time. I nearly killed him once in an elevator, because my reaction to being grabbed like that is to hit someone as hard as I could with my elbow, and I refrained only because it was my first Nebula award ceremony as the editor of F&SF. I had a thought that maybe whoever groped me was someone famous—and it was a frail Asimov. His delicate ribcage was only a few inches from my deadly elbow. That would have been bad.

Needless to say that while the rest of the world admires the heck out of that man, I do not. I didn’t know much about Campbell other than the stories the old timers told about him, and I had avoided reading/listening to stories about Hubbard. OMG, that man should have been in jail. Heinlein, whom I had met and who was bombastic as hell, came out the best.

Kudos for Alec for writing about all of these men, warts and all. I love the analysis of what sf became because of them and what still needs to be changed. As worthy a book as I have read in years.

Rose, Lucy, “The Worst Thing that Can Happen is You Suck,” The Hollywood Reporter, June 5, 2024. This is a roundtable interview with actors John Hamm, Matt Bomer, Nicholas Galitzine, Clive Owen, David Oyelowo, and Collum Turner. I love the roundtables that The Hollywood Reporter does because they get a group of professionals together to discuss their art. There’s always something in the roundtables that mean something to me. Here, there are quotes I circled from Clive Owen…

I have never listened to anybody else. Ultimately, you are the one who has to go to work every day. I do what I want to do because that’s what’s going to sustain me through it.

…and John Hamm…

But yeah, to Clive’s point, agents and managers can all bat a thousand in the rearview mirror, they can always tell you what they thought after the thing came out and it was good or bad. It’s in the moment that you have to make the decision. And the worst thing that can happen is you suck.

I love that last part, which is also the title of this piece in the printed form. “The worst thing that can happen is you suck.” Exactly. And that’s not so very bad, now is it?

Silva, Daniel, A Death in Cornwall, HarperCollins, 2024. I’m fascinated by the way that Daniel Silva’s Gabriel Allon series has changed since the Trump era began. Silva’s books were always on the edge of modern politics, as close to real politics as possible. But it became clear that Silva was struggling with the constant changes instigated by Trump in his first term, and then the worldwide unrest in Biden’s term—from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the utter mess in the Middle East.

Silva, Daniel, A Death in Cornwall, HarperCollins, 2024. I’m fascinated by the way that Daniel Silva’s Gabriel Allon series has changed since the Trump era began. Silva’s books were always on the edge of modern politics, as close to real politics as possible. But it became clear that Silva was struggling with the constant changes instigated by Trump in his first term, and then the worldwide unrest in Biden’s term—from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the utter mess in the Middle East.

Silva solved it by returning Allon to his roots; he was a painter and an art restorer who also became a spy. (And then a super spy.) Now, he has retired and gone back to restoring amazing paintings…and solving worldwide art-related crimes. This crime starts in Allon’s former residence on the Cornish coast of England, with the death of a reknown art history professor and scurries along from there. Highly recommended.

Stoynoff, Natasha,“Brooke Shields Wants You To Know She Is Just Fine,” AARP Magazine, April/May 2024. Because of the year I had in 2024, I sometimes find it hard to remember articles I had marked as long ago (and far away) as August. I have dumped a few magazines without recommending anything from them because, for the life of me, I have no idea why I marked a certain page.

Not so with the April/May AARP Magazine. I picked it up to see what I had recommended, didn’t see my usual mark, and frowned at it. I distinctly remember reading the Brooke Shields interview and finding it both wise and inspiring.

Brooke Shields and I are of an age. She’s younger, but not by much. And by the time she was being exploited all over the world, I was old enough to feel icky about it, but young enough not to know why. This article addresses her past, yes, but it also looks at her now. At least from this interview, it seems that she has accepted both her age and the changes that aging brings. I recommend this article to everyone.

The Happy Writer Book is Finally Here!

Tuna’s Video

This morning, while I waited for Gordon’s MRI, my phone made this video for me complete with the overly sentimental music. Apparently I take a lot of pictures of the orange menace. He got in trouble yesterday because he was very pushy about shoving the dogs aside to sit in a specific spot on my lap.

Behold, Tuna the Cat.

He can never see this, or his ego will be even bigger.

The post Tuna’s Video first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend

Here are seven author shoutouts for this week. Find your favorite author or discover an…

The post 7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend appeared first on LitStack.

Locked In - Book Review

Locked In (Zombie Bedtime Stories #1)by Thea Isis Gregory

Locked In (Zombie Bedtime Stories #1)by Thea Isis GregoryWhat is it about:Haley is enjoying her new job as a paramedic on a beautiful summer’s day. Not even her dour and sullen partner, Frank, can deflate her enthusiasm for life. Responding to a routine call near her former high school, she is excited to see her old hang-out spot, the park. On arrival, something is clearly wrong, and Haley is attacked by one of her old friends. Soon, she begins to experience disturbing changes in her personality and food preferences, until she wakes up a zombie. Her consciousness is suspended in a body that she can't control, and she needs to find a way to escape.

What did I think of it:I'm always on the lookout for a good zombie story, so when I encountered the author on Social Media and she mentioned zombies I immediately got hold of her Zombie Bedtime Stories series and read the first book as it's only 18 pages.

And what a cool read!

It's told from the perspective of someone who has been infected and it's so well done! I was immediately hooked and wondering how this could and would end. Those 18 pages flew by. I was very glad I immediately got the whole series of short stories, because this one tastes like more!

You bet you can expect a review of the secons book real soon!

Why should you read it:This is an amazing zombie read!

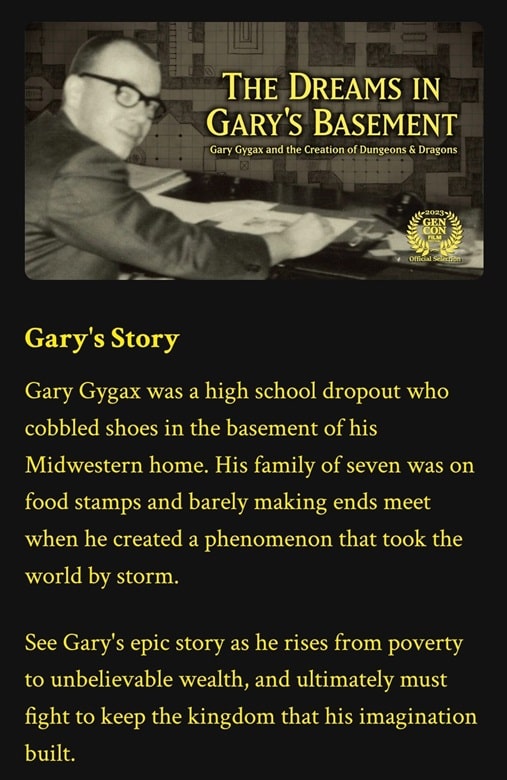

The Dreams in Gary’s Basement: Gary Gygax and the Creation of Dungeons & Dragons

The Dreams in Gary’s Basement, Blu Ray version (rpghistory.net, 2023)

The Dreams in Gary’s Basement, Blu Ray version (rpghistory.net, 2023)

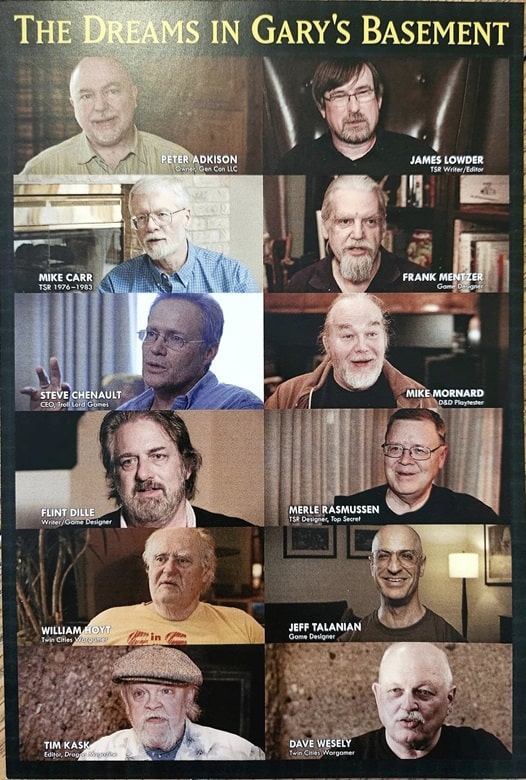

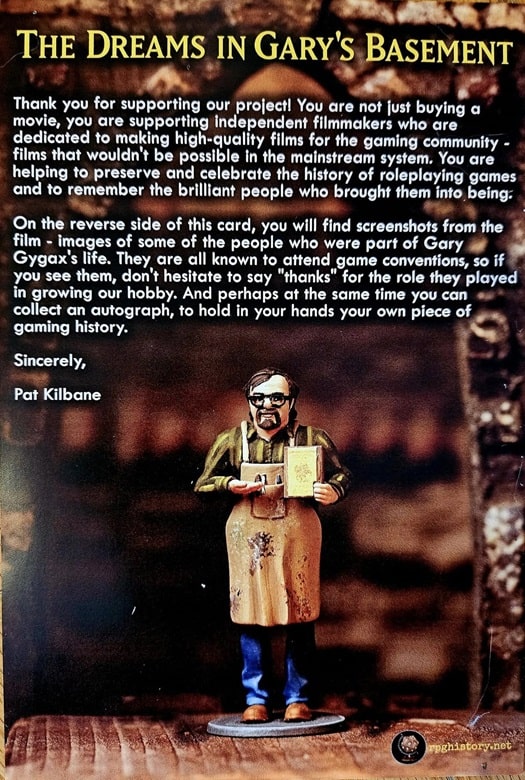

On the eve of Gary’s Gygax’s birthday, July 26, 2019, I was in sunny California getting ready to be interviewed by the Dorks of Yore for their documentary, The Dreams in Gary’s Basement: Gary Gygax and the Creation of Dungeons & Dragons.

The interview touched on my experiences working with Gary from 2005–2008, a time that I will always cherish. Gary was so generous with me — a friend and a mentor who not only showed me the ropes, but also put trust in me. It was such an honor and a privilege to get to work with one of my childhood idols.

Getting ready for the interview

Getting ready for the interview

Here I am a few years ago at the filming. The interview was conducted by Pat Kilbane and his crew, who reorganized my room at the Marriott just outside of Hollywood. Stephen Chenault of Troll Lord Games was scheduled to be interviewed before me. It was a lot of fun!

It was an incredible honor to be included in this discussion on the history of Dungeons & Dragons, and Gary Gygax’s role in vaulting his co-creation to the stratosphere. My joy is evident in this photo. I had the privilege to work as Gary’s co-author in his final years (2005 – 2008), and I was so happy to share my appreciation of his genius.

The Dreams in Gary’s Basement

The Dreams in Gary’s Basement

The Dreams in Gary’s Basement is very well done, and if you are a fan of D&D, including the history of its creation and meteoric rise to popularity and fame, then I urge you to check it out at rpghistory.net.

Gary, as many of you know, was the co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, a game that has enjoyed 50 years of success. Gary taught me a lot, even when he wasn’t actively teaching or instructing me on the development of Castle Zagyg (or Castle Greyhawk, to those who know). I recently relayed the story of Gen Con in 2007, when Gary was signing autographs at the Troll Lord Games booth.

Bonus card included with the Kickstarter version

The line snaked through the halls, filled with fans who wanted to have something signed, or to shake his hand, take a photo, or to tell him how much his creations meant to them or changed their lives. It was inspiring for me to see how he handled his enthusiastic fandom. He listened to and spoke with every one of them. He treated them like fellow gamers, like peers, and he was humble and thankful for their kind words.

It was really nice to see. Gary was more than just a genius creator of games. He was a good guy.

Cheers, Gary!

Jeffrey P. Talanian’s last article for Black Gate was Hal Clement Helped Launch My Writing Career. He is the creator and publisher of the Hyperborea sword-and-sorcery and weird science-fantasy RPG from North Wind Adventures. He was the co-author, with E. Gary Gygax, of the Castle Zagyg releases, including several Yggsburgh city supplements, Castle Zagyg: The East Mark Gazetteer, and Castle Zagyg: The Upper Works. Read Gabe Gybing’s interview with Jeffrey here, and follow his latest projects on Facebook and at www.hyperborea.tv.

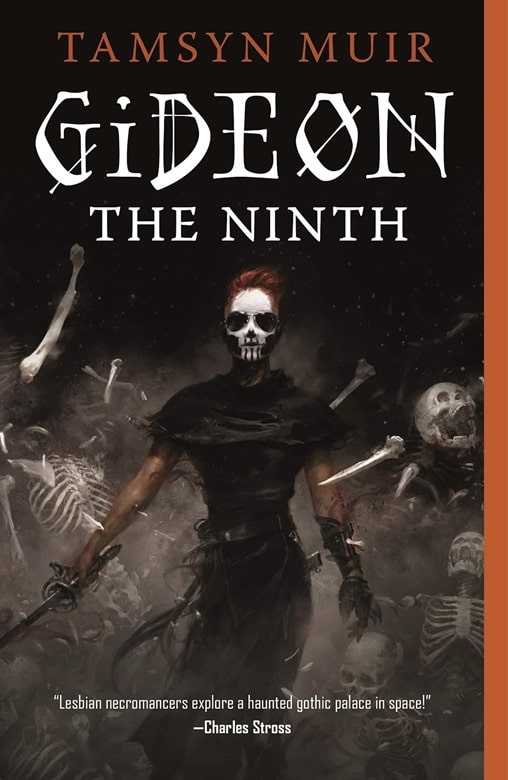

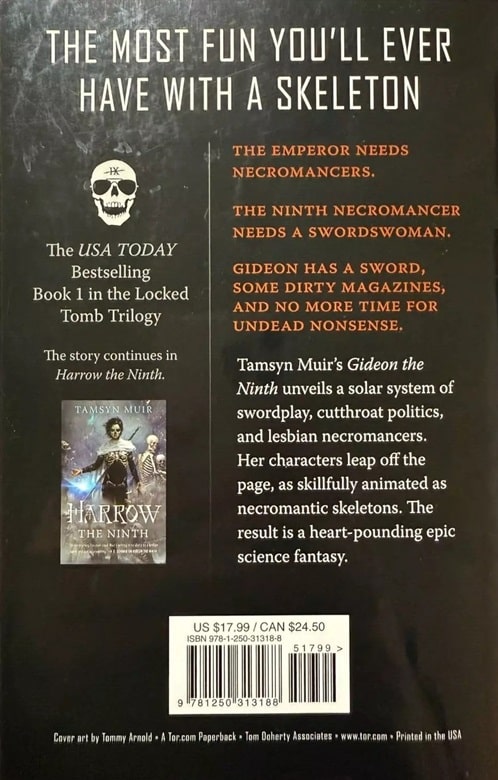

A Locked Tomb Mystery in Space: Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir

Gideon the Ninth (Tor Books, September 10, 2019). Cover by Tommy Arnold

The back cover of the hardcover edition of Gideon the Ninth features this assessment from writer Warren Ellis: “The author is clearly insane.”

Three things made me shunt Gideon the Ninth to the front of my TBR stack. First, both my older son and his girlfriend read it, and, once finished, they promptly named their cat Harrow after one of the two main characters. Second, the cover art jumped out like an All Hallows spotlight. Third, that Ellis quote grabbed me by the frontal lobes. A novel featuring skeletons and sword-wielding necromancers written by a writer five cans short of a six-pack? Sign me up, buttercup.

Finally, in the interests of truth-telling or perhaps over-sharing, I must add that a fourth element convinced me to delve into Gideon the Ninth, and that was when I spotted a copy on the shelves at Chaucer’s Books in California, and cracked the cover to explore the opening paragraph. It reads as follows:

In the myriadic year of our Lord –– the ten thousandth year of the King Undying, the kindly Prince of Death! –– Gideon Nav packed her sword, her shoes, and her dirty magazines, and she escaped from the House of the Ninth.

I was hooked. There’s nothing like a practical protagonist. Sword and shoes, check. Dirty magazines? Clearly a must. Next stop, adventure!

Gideon’s author, Tamsyn Muir, hails from New Zealand, land of the flightless kiwi, and perhaps her nation’s geographic (indeed, geologic) isolation is what prompted her to cast the requisite bones to write this dark but often hilarious tale. (The dialogue, in particular, is a hoot.)

Without going into a dull, useless, and surely uninspiring plot summary, let’s just say that Muir begins on a haunted planet where necromancy is the norm, and where just about nobody alive seems to live –– except for Gideon, who is training to be the galaxy’s best sword-arm, and her much-hated nemesis, Harrowhark Nonagesimus.

Harrow, after all, commits daily sacrilege by referring to proud Gideon as Griddle.

Griddle’s –– sorry, Gideon’s –– daily goal: to get off-planet. Anyplace elsewhere will do. Harrowhark’s goal: to foil Gideon, because –– well, Harrow knows what Gideon does not, that in the very near future, the Nine Houses will convene for a lethal tournament, and Harrow will need Gideon to become her right-hand girl, her one and only cavalier, in order to…

Dag-nabbit, I said I wouldn’t do a plot summary, and look what just happened. Plot! Summarized.

At rock bottom, the hook is that Gideon and Harrow are going to have to work together, because if they don’t, the really nasty side of all things necromantic will seize control of the Emperor’s depleted band of revenant Lyctors, and Lyctors are –– no, sorry, you’ll have to figure that out for yourself.

This could be disastrously simplistic in another writer’s hands. Long-time rivals, forced to work together? Yawn.

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie (WSP/Pocket Books, 1979)

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie (WSP/Pocket Books, 1979)

But Muir has read her Dame Agatha, a la And Then There Were None, and she takes flight from there, bending the tropes of the “locked room mystery” into a “locked tomb mystery.” Sounds cheesy? It isn’t. Muir leavens the super-sharp, bite-me dialogue with creepy grossness straight out of Clive Barker. The action sequences are top-notch, with swords and magic and tricks and traps and self-sacrifice of the highest order. The climactic battle rages for no less than thirty-five pages, and it never flags, not once.

Speaking as a writer, that’s a particularly impressive high-wire act. Action sequences force their authors to forgo most of the tricks in the creative writing toolbox. Asides have to be strictly limited; musings and recollections even more so. Metaphors must be kept to a tidy minimum. Basically, combat scenes are a tight, focused series of “And then, and then, and then, and then!” No letting up allowed, and the ultra-efficient description required has to be vivid, dead-accurate, and electrifying. A great many very well-known authors can’t keep this particular kind of balloon aloft for long, but Muir can, and does. It’s frankly thrilling.

For those ready to frown on yet another book featuring necromancy, never fear. Muir trades in specifics. Each of the Nine Houses has its own specialty. Harrowhark’s particular focus is bones, such that skeletal material is, for her, plastic, expandable, shrinkable. At her will, bones animate. Her Sixth House rival, Sextus (who claims to be the greatest necromancer of his generation) brings a skill set more akin to a D&D cleric, allowing him to impact flesh, living, dead, and in between. The Eighth House channels (and sometimes siphons) departed souls. And so on.

The tournament commences. Each house couplet, necromancer and attendant cavalier, sets out to discover the path to becoming a Lyctor. Their hosts claim not to know the answer. We the readers certainly don’t know the answer. But Muir does. Even when the book leaves a few dangling questions at story’s end, I never had the sense that I was in the hands of, say, the makers of Lost, where in fact nobody knew what was going on.

The second and third books in The Locked Tomb series: Harrow the Ninth and Nona the Ninth

(Tor Books, August 4, 2020 and September 13, 2022). Covers by Tommy Arnold

By choice, I treated Gideon the Ninth as a highly enjoyable one-off, but in fact it’s a quartet, with Harrow the Ninth following next, then Nona the Ninth, to be rounded off by Alecto the Ninth (coming, we are told, soon). The evidence so far suggests that Muir has her universe knitted together and under control, and the fact that she’s still exploring it is a bonus round, not a charlatan’s dodge.

Meanwhile, I suppose it’s only mete and proper to address the front-cover quote, from Charles Stross:

Lesbian necromancers explore a haunted gothic palace in space!

This is all factual enough, but a tad gratuitous, since Gideon never pursues either long-term romance or specific sex scenes. True, Gideon’s particular predilections influence how she interacts with a handful of her fellow tournament contestants, but mostly, her preferences matter about as much as her shoe size. Honestly, this is a relief. How pleasant to discover a book where sexuality, of whatever type, is just one part of the larger whole, and not something to be exploited for the sake of titillation, bodice-ripping or otherwise.

Harrow the Cat

Harrow the Cat

I expect I’ll catch up with Harrow (the book, not the cat) later in the year. Although come to think of it, perhaps I’ll visit my son, too, in which case, I’ll have the opportunity to read Harrow the Ninth with Harrow the Cat purring on my lap.

Now that’s a sequel worth anticipating.

Onward.

Mark Rigney is a writer and long-time Black Gate blogger. His work on this site includes original fiction and perennially popular posts like “Adventures in Spellcraft: Rope Trick.” His new novel, Vinyl Wonderland, dropped on June 25th, 2024. Reviewer Rich Horton said of Vinyl Wonderland, “I was brought to tears, tears I trusted. A lovely work.” His favorite review quote so far comes from Instagram: “Holy crap on a cracker, it’s so good.” A preview post can be found HERE, while his website lives over THERE.

The Book Goblin

So I’ve been living under a holiday rock. The tree is still up. Yes, I know, but it’s pretty. I will take it down, leave me alone.

Anyway, I just now saw this.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Elisabeth Wheatley (@elisabethwheatley)

I think Elizabeth Wheatley is in Austin and I so owe her a lunch and a coffee. Thank you for making my day! You can find Elizabeth’s books at her online home, at https://elisabethwheatley.com/.

The post The Book Goblin first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Well…It’s 104 Stories Now…

The Series Collide Kickstarter is winding down. As of this writing, we have hit two stretch goals, which brings the total of short stories you’ll get when you back the Kickstarter to 104. Given the unpredictability at the end of a Kickstarter, we might add anywhere from two to four more stories to that total as we hit even more goals.

That’s a lot of reading.

I don’t know about you folks, but I’m finding myself in great need of escapism right now. Fiction is the best way to block out the problems of 2025. What could be better than concentrating on some made-up adventures right now?

The Series Collide Kickstarter features 100 short stories in 36 series. Fifty stories are by me and fifty are by Dean. Think of the five books in the Kickstarter as a massive sampler. You can sample each series and if you like what you’ve read, you’ll have a lot more series reading ahead of you.

As an illustration, read this week’s Free Fiction story. It’s from my Retrieval Artist series. If you like it, there are 15 novels to grab your attention.

So head on over to the Kickstarter. In addition to the five Series Collide books, you can find other short story collections as well as some writing workshops and the opportunity to submit stories to Pulphouse Magazine (which is usually closed to submissions.)

An Emissary For Our Own Fate | “The Emissary” by Yoko Tawada

Yoko Tawada’s The Emissary is a breathtakingly light-hearted meditation on mortality and fully displays what…

The post An Emissary For Our Own Fate | “The Emissary” by Yoko Tawada appeared first on LitStack.

Teaser Tuesdays - The Teller of Small Fortunes

I'm still reading this one. So far this is a really fun read, but I got stuck somewhere without physical book, so started on an e-book and read that first before continuing with this book.

But here with two unwanted escorts of dubious reputation, it had become something loud and unfamiliar. But not, thought Tao as their small party clanked on, entirely unpleasant.

(page 38 The Teller of Small Fortunes by Julie Leong)

---------

Teaser Tuesdays is a weekly bookish meme, previously hosted by MizB of Should Be Reading. Anyone can play along! Just do the following: - Grab your current read - Open to a random page - Share two (2) “teaser” sentences from somewhere on that page BE CAREFUL NOT TO INCLUDE SPOILERS! (make sure that what you share doesn’t give too much away! You don’t want to ruin the book for others!) - Share the title & author, too, so that other TT participants can add the book to their TBR Lists if they like your teasers!

Book review: The Way Up is Death by Dan Hanks

Book links: Amazon, Goodreads

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Dan is a writer, editor, and vastly overqualified archaeologist who has lived everywhere from London to Hertfordshire to Manchester to Sydney, which explains the panic in his eyes anytime someone asks “where are you from?”. Thankfully he is now settled in the rolling green hills of the Peak District with his human family and fluffy sidekicks Indy and Maverick, where he writes books, screenplays and comics.

Publisher: Angry Robot (January 14, 2025) Length: 400 Pages Formats: ebook, paperback

What do you get when you throw 13 strangers into a deathtrap tower, tell them to “ASCEND,” and watch chaos unfold? You get The Way Up is Death, Dan Hanks’ twisted love child of The Hunger Games, Portal, and the most stressful video game session ever.

And it’s great.

The setup is simple: one day, a floating tower shows up in England. A group of randoms—disillusioned teachers, underappreciated artists, and even an obnoxious influencer—find themselves zapped to its doorstep. Their mission? Survive.

Hanks takes this bonkers premise and runs with it, and the result is exceptional. A true nail-biter that toes the line between horror, sci-fi, and emotional gut punches. Each level of the tower resembles a sadistic escape room designed by a fever-dreaming psychopath. You never know what’s coming, and that’s half the fun.

The cast is awesome. There’s Alden, a grieving teacher, trying to find meaning; Nia, a game designer desperate to prove herself; and Earl and Rakie, a father-daughter duo you’ll probably root for. And then there’s Dirk, the self-absorbed influencer you’ll love to hate—seriously, he’s the worst, and you’ll cheer every time the tower messes with him.

But it’s not all blood and guts. Hanks sneaks in his sharp social commentary, thoughts on grief, loneliness, and even influencer culture. Somehow, between all the horror and humor, he sneaks in moments that genuinely make you feel things. Like, big existential feelings.

Shortcomings? Well, there’s at least one. Some characters are so obviously redshirts that their brutal demises aren’t surprising—they’re expected. The only question is the order in which they’ll die. Plus, they’re all bland and forgettable, especially when compared to a few key players.

Relentlessly paced and surprisingly heartfelt, The Way Up is Death is addictive. It’s weird, wild, and brutal. And if you’re interested in my opinion, it’s a must-read.

Recent comments