Feed aggregator

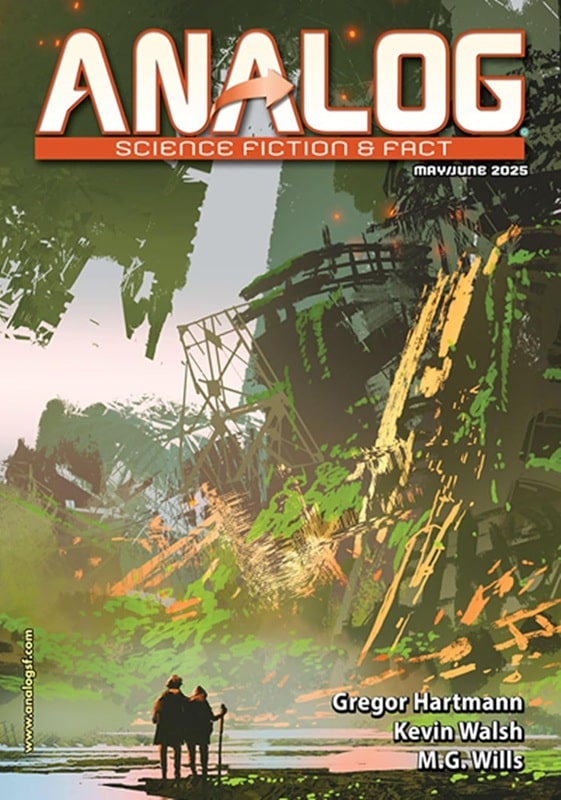

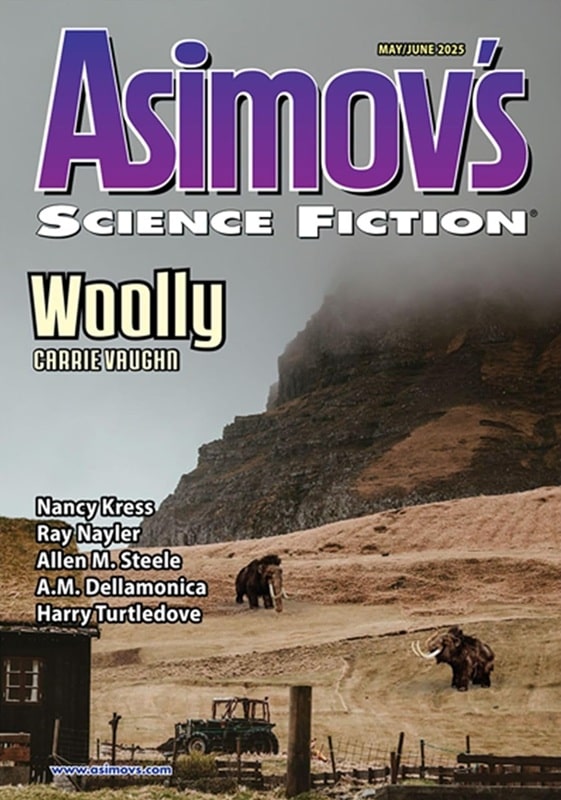

Mechanical Trees and Mini-Woolly Mammoths: May-June Print Science Fiction Magazines

May-June 2025 issues of Analog Science Fiction & Fact and Asimov’s Science

Fiction. Cover art by Tithi Luadthong/Shutterstock, and IG Digital Arts & Annie Spratt

Back in February I was surprised to learn that the last surviving print science fiction magazines, Analog, Asimov’s Science Fiction, and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, had all been sold to Must Read Books, a new publisher backed by a small group of genre fiction fans. I was very sad to see Analog & Asimov’s leave the safe harbor of Penny Press, where they’ve both sheltered safely for very nearly three decades as the magazine publishing biz underwent upheaval after upheaval.

But I was nonetheless cautiously optimistic. The magazines couldn’t continue to survive as they were, with 25+ years of slowly declining circulation — and indeed F&SF, while it claims to be an ongoing concern, has not published a new issue in nearly a year.

But after four months, that optimism is rapidly fading. The first issues from Must Read, the May-June Analog and Asimov’s, technically on sale April 8 – June 8, have yet to appear on the shelves at any of my local bookstores, and there’s been no word at all at when we can expect the July-August issues, scheduled to go on sale today. And there’s no whisper of when we might expect to see a new issue of F&SF at all.

The March-April issues of Analog and Asimov’s SF, still on the shelves at Barnes and Noble in Geneva, Illinois on June 7, 2025

The March-April issues of Analog and Asimov’s SF, still on the shelves at Barnes and Noble in Geneva, Illinois on June 7, 2025

So why are there photos of the May-June issues at the top of this column? Are they ChatGPT hallucinations?

Nope. If you have a digital subscription, your issues of Analog and Asimov’s arrived on time on April 8. And I’m told that folks with print subscriptions received hard copies in the mail around May 15. So copies do, in fact, exist. But the new owners don’t seem to have the myriad complexities of distribution figured out yet.

A shame, since I’d love to get my hands on the latest issues (after having my copies mangled by the post office in the 80s, I switched to buying them from bookstores, and have stuck with that method for the last 40 years). They’re just as enticing as usual, with contributions from Nancy Kress, Allen M. Steele, Ray Nayler, Harry Turtledove, Steve Rasnic Tem, Carrie Vaughn, A.M. Dellamonica, Brenda Cooper, Shane Tourtellotte, Mark W. Tiedemann, Gregor Hartmann, Howard V. Hendrix, and many more.

Mina at Tangent Online enjoyed the latest Asimov’s.

“The Hunt for Lemuria 7” by Allen M. Steele is a sequel to “Lemuria 7 Is Missing” [from the July/August 2023 issue]. The story is a mosaic of various sources piecing together the efforts to find the missing crew of six like a lunar Mary/Marie Celeste. Merlin Feng is determined to find out what happened to his mentor and his mentor’s daughter and former girlfriend, Amelia. He designs robotic rovers with advanced AI systems to investigate the site of their disappearance and other sites where Transient Lunar Phenomena have been observed. Five years after the disappearance, Amelia turns up at the Great Wall of China. All she can say is that she has been sent back to warn others not to set foot on the moon…

“In the Forest of Mechanical Trees” by Steve Rasnic Tem is a thoughtful and thought-provoking story about a world living with climate change and other environmental ravages. An elderly couple run a theme park in the ever-growing Arizona desert. The park includes trees that soak up carbon dioxide and sculptures to commemorate the growing list of extinct species. The park’s staff are determined in their fight against the elements and it’s curiously not a depressing story. But it is a sobering reminder of the direction humanity is heading in.

“The Fight Goes On” by Harry Turtledove imagines a Sarajevo in 1914 filled with time travellers: some trying to stop the murder of Franz Ferdinand; some trying to ensure it happens. We follow the attempts of one time traveller. It was well-written and amusing but didn’t grab me.

In “The Tin Man’s Ghost” by Ray Nayler, we meet Sylvia Aldstatt again: the agent who can speak with the dead with the help of alien technology. We are in the McCarthy era but in a world changed by the use of technology reverse engineered from a crashed flying saucer. Sylvia’s mission this time is to talk to the ghost of a robot (also referred to as a war machine or the Tin Man by others, as a “mechanical” by itself). Sylvia discovers that all mechanicals were given the memories of one man, Alvin Greenly, but that they diverged over time. And she discovers that mechanicals are capable of courage and sacrifice. Sylvia also meets Oppenheimer but that is not the main focus of the story; the main focus is on stopping, or at least slowing down, the development of the atomic bomb. The mechanical, Bill, worms its way into our hearts, giving the last line of the story its full poignancy… an excellent novelette.

“Trial by Harry” by Michael Libling is ultimately a horror story. A new drug is on trial for older people in a vegetative state. Harry is visited faithfully by his two surviving children as he slowly comes back up from the bottom of a deep well. We see his memories as he recovers them and slowly we realise that Harry was not a good man. The title takes on a chilling double meaning as you reach the end of the story.

“Woolly” by Carrie Vaughn is a warm tale. Joy runs a rescue farm for abandoned, genetically modified, mini-woolly mammoths. When the government decides to put them all down, Joy needs to win more time to fight the decision in court. The tale ends on a light note, with the reader rooting for Joy and her charges.

Read Mina’s complete review here.

The new Analog is reviewed by the always reliable Victoria Silverwolf at Tangent Online. Here’s a sample.

“Isolate” by Tom R. Pike takes place in a galactic empire ruled by a monarch who is worshipped as a deity. The protagonist is a cleric and a linguist, sent to a remote region of a planet recently annexed to the empire. Her task is to determine if the local language is related to the empire’s official language, and thus acceptable, or if it must be eliminated…

In “The Robot and the Winding Woods” by Brenda Cooper, an elderly couple maintains a campground, even though there have been no visitors for many years. A robot arrives to tell them that the area is to be returned to pure wilderness, and that they must leave. Another fact revealed by the robot changes the situation…

“Mnemonomie” by Mark W. Tiedemann takes place in a society where boys become men by having their memories completely replaced, instantly changing them from adolescents interested in aggressive sports to adults with careers. One such young man suffers brain injury during an attack by a rival team, so the process is not completely successful, leaving him with memories of his past. In this way, he learns something about the world in which he lives…

“The Scientist’s Book of the Dead” by Gregor Hartmann takes place years after a devastating war wiped out most of humanity and a revolution resulted in a world ruled by technocrats. The western hemisphere is completely depopulated and left as a wilderness area. The aging leader of the revolution and his chief of staff, a young woman bred to be at the peak of human ability, lead the narrator and other technocrats on a hike in an otherwise deserted North America… The story offers much food for thought, without easy answers.

The two characters in “Siegfried Howls Against the Void” by Erik Johnson are sentient starships, many lightyears apart in their separate voyages. Over millennia, they send occasional messages to each other. One of them, identified as male, comes to depend on the signals from the other, identified as female. In addition to making the starships seem like people, the author also anthropomorphizes stars and planets, describing them as mothers and their children. Despite having no human characters, this is a romantic story, with interstellar exploration as a source of emotional wonder and despair… This is the author’s first published story, and it reveals a rich imagination and a lush narrative style that could benefit from a little discipline.

The novella “Bluebeard’s Womb” by M. G. Wills deals with a project to create a uterus within a man’s body, which can then have an embryo implanted in it so the man can give birth by Caesarean section. The first volunteer is an acquaintance of the woman in charge. He has his own agenda, which only becomes clear after the child is born. Although this is not the first story to feature male pregnancy, it is unusually realistic and scientifically plausible… this provocative work is sure to create controversy. Readers’ opinions on the issues raised in it will determine how they react to it.

Read Victoria’s full review here.

Here’s all the details on the latest SF print mags.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

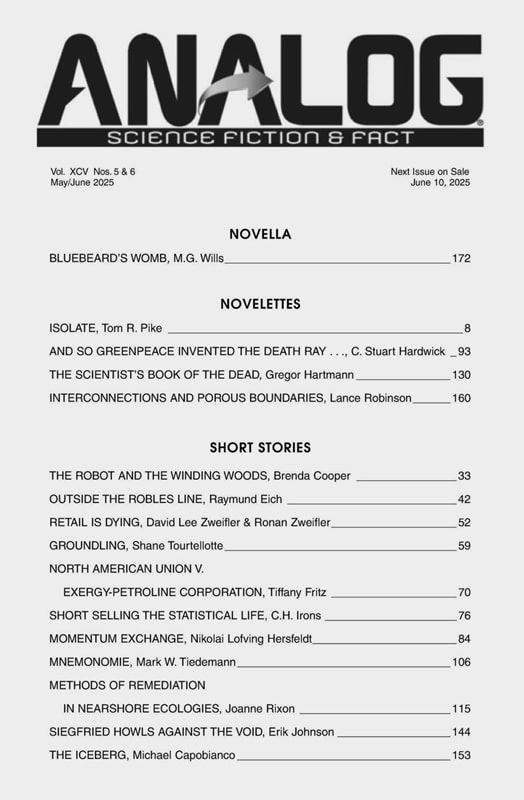

Analog Science Fiction & Science Fact, May-June 2025 contents

Editor Trevor Quachri gives us a tantalizing summary of the current issue online, as usual.

Unlike this issue, there’s no grand unifying theme for May/June other than “good stories,” but that’s okay: it’ll keep you on your toes!

First up is a bit of classic Schmidtian linguistic science fiction in “Isolate” by Tom R. Pike. We also anchor the issue with what’s likely to be the definitive hard SF take on a classic SFnal “What If . . . ?” scenario, in “Bluebeard’s Womb,” by M.G. Wills, plus a bunch of other fine fiction, including a game of cat and mouse between a jailer and his prisoner, only on a grand scale, in “Momentum Exchange,” by Nikolai Lofving Hersfeldt; an older couple trying to make it in a world that no longer has room for them in a very concrete way in “The Robot and The Winding Woods,” by Brenda Cooper, plus much, much more, from folks like C. Stuart Hardwick, Kelsey Hutton, Michael Capobianco, and Gregor Hartmann.

Here’s the full TOC.

Novella

“Bluebeard Womb” by M.G. Wills

Novelettes

“Isolate” by Tom R. Pike

“And So Greenpeace Invented the Death Ray…” by C. Stuart Hardwick

“The Scientist’s Book of the Dead” by Gregor Hartmann

“Interconnections and Porous Boundaries” by Lance Robinson

Short Stories

“The Robot and the Winding Woods” by Brenda Cooper

“Outside of the Robles Line” by Raymund Eich

“Retail is Dying” by David Lee Zweifler & Ronan Zweifler

“Groundling” by Shane Tourtellotte

“North American Union V. Exergy-Petroline Corporation” by Tiffany Fritz

“Short Selling the Statistical Life” by C.H. Irons

“Momentum Exchange” by Nikolai Lofving Hersfeldt

“Mnemonomie” by Mark W. Tiedemann

“Methods of Remediation in Nearshore Ecologies” by Joanne Rixon

“Siegfried Howls Against the Void” by Erik Johnson

“The Iceberg” by Michael Capobianco

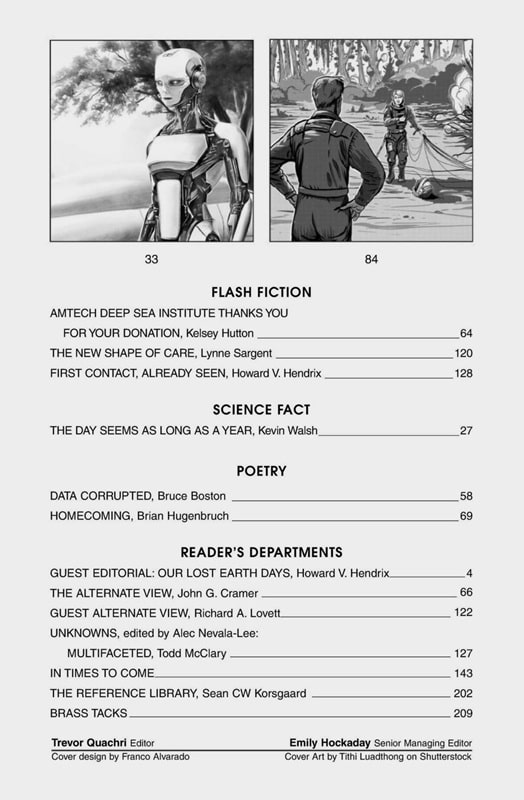

Flash Fiction

“Amtech Deep Sea Institute Thanks You For Your Donation” by Kelsey Hutton

“The Shape of Care” by Lynne Sargent

First Contact, Already Seen” by Howard V. Hendrix

Science Fact

The Day Seems as Long as a Year, by Kevin Walsh

Poetry

“Data Corrupted” by Bruce Boston (Poetry)

“Homecoming” by Brian Hugenbruch (Poetry)

Reader’s Departments

Guest Editorial: Our Lost Earth Days by Howard V. Hendrix

The Alternative View, John G. Cramer

Guest Alternative View by Richard A. Lovett

In Times to Come

The Reference Library by Sean CW Korsgaard

Brass Tacks

Asimov’s Science Fiction, May-June 2025 contents

Asimov’s Science Fiction

Asimov’s Science Fiction, May-June 2025 contents

Asimov’s Science Fiction

Sheila Williams provides a handy summary of the latest issue of Asimov’s at the website.

We have three thrilling novellas crammed into our May/June 2025 issue! The issue opens with Allen M. Steele’s exciting and enigmatic “Hunt for Lemuria 7”! Allen takes us back to the Moon where the mysterious disappearance of Lemuria 7 and its crew becomes a conundrum. John Richard Trtek delivers an exquisitely told tale set on a far-future Earth where humans who wish to emigrate to an alien planet must first embark on “The Passage.” Nancy Kress wraps up the issue with the conclusion to her brilliant hard SF story about “Quantum Ghosts”! You won’t want to miss any of these exciting works.

A.M. Dellamonica squeezes a movie-length suspense/romcom film into a short story about “The Humming of Tamed Dragons”; Michael Libling spins a deceptive horror story about what it means to endure “Trial by Harry”; Carrie Vaughn conveys the heartfelt story of a woman’s attempt to rescue “Woolly”; Ray Nayler’s novelette tells the complex tale of a retired Sylvia Altstatt called back into service by “The Tin Man’s Ghost”; Steve Rasnic Tem invites us “In the Forest of Mechanical Trees” where an elderly group of people who maintain a sculpture park try to create a whimsical sense of normalcy for a family escaping the ravages of climate change; and Harry Turtledove’s time travel tale about frustrating and tragic historical events reveal why “The Fight Goes On.”

Robert Silverberg’s Reflections muses about “The Other Schliemann”; James Patrick Kelly’s On the Net takes some “Moonshots”; Kelly Jennings’s On Books looks at works by T. Kingfisher, Madeline Ashby, John Wiswell, Cebo Campbell, Michael Bérubé, and others; Kelly Lagor’s Thought Experiment considers “Crime and Punishment in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange”; plus we’ll have an array of poetry you’re sure to enjoy.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

Novellas

“The Hunt for Lemuria 7” by Allen M. Steele (Novella)

“Quantum Ghosts (Part II)” by Nancy Kress (Novella)

“The Passage” by John Richard Trtek (Novella)

Novelette

“The Fight Goes On” by Harry Turtledove (Novelette)

“The Tin Man’s Ghost” by Ray Nayler (Novelette)

“Trial by Harry” by Michael Libling (Novelette)

Short Stories

“In the Forest of Mechanical Trees” by Steve Rasnic Tem (Short story)

“The Humming of Tamed Dragons” by A.M. Dellamonica (Short story)

“Woolly” by Carrie Vaughn (Short story)

Poetry

“Baggus Plasticus” by Ciarán Parkes (Poetry)

“Introducing My Friends to My Dad” by Chiwenite Onyekwelu (Poetry)

“Stellarium” by Stuart Greenhouse (Poetry)

“Micro Circuit” by Sai Liuko (Poetry)

“Train” by David Rogers (Poetry)

Departments

Guest Editorial: The Writes of Spring by Rick Wilber

Reflections: The Other Schliemann by Robert Silverberg

On the Net: Moonshots by James Patrick Kelly

Thought Experiment: Crime and Punishment in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange by Kelly Lagor

On Books by Kelly Jennings

Next Issue

Analog, Asimov’s Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction are available wherever magazines are sold, and at various online outlets. Buy single issues and subscriptions at the links below.

Asimov’s Science Fiction (208 pages, $8.99 per issue, one year sub $47.97 in the US) — edited by Sheila Williams

Analog Science Fiction and Fact (208 pages, $8.99 per issue, one year sub $47.97 in the US) — edited by Trevor Quachri

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (256 pages, $10.99 per issue, one year sub $65.94 in the US) — edited by Sheree Renée Thomas

The May-June issues of Asimov’s and Analog are officially on sale until June 8, but (assuming they ever show up at all) likely will be on shelves a little longer than that. See our coverage of the March-April issues here, and all our recent magazine coverage here.

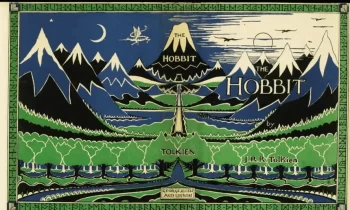

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Five: From the Beginning — The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

Chapter 1, An Unexpected Party – The Hobbit

Fifty years ago, when I first read this book, I didn’t imagine I’d still be reading it so many years later. Heck, I doubt I could have even imagined being as old as I am now. But I do reread it every few years. When I revisit The Hobbit, my journey is bathed in nostalgia as much as with the simple enjoyment caused by reading a charming book that I happen to know inside out, from the opening line above on through to the very end.

In my initial article on half a century of reading Tolkien back in January, I described my dad trying to get our first color tv in time to watch the Rankin & Bass The Hobbit. Remembering that again last week left me thinking more of my dad, now gone nearly 24 years, than the book. He was ten years younger than I am now when the movie first aired, which makes me feel incredibly old at the moment. For such a conservative man, he was excited to see it — admittedly, in a restrained way. I think we liked it well enough, but leaving out Beorn irked us both. Beyond Tolkien’s books, our fantasy tastes rarely coincided (I’ve got a shelf full of David Eddings books he bought, if anyone’s interested), but with The Hobbit and LOTR, we were in complete agreement.

What’s there to say about The Hobbit here on Black Gate? Nothing, really. I imagine most visitors here have read it, many more than once, and have their own ideas on it. It’s one of the most widely read books in the world. Instead, I’m going to discuss some adaptations of the book. But first, a summary.

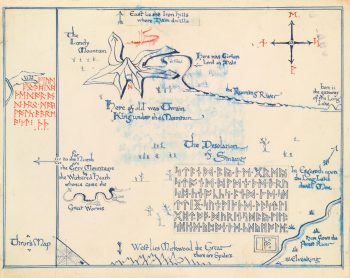

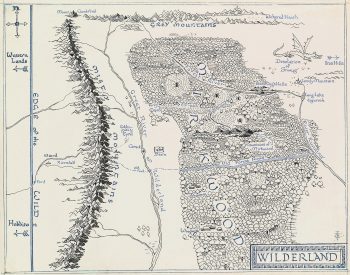

Map of the Lonely Mountain by JRR Tolkien

Map of the Lonely Mountain by JRR Tolkien

Hobbits are Tolkien’s slightly comical take on the staid British country folk. Their homeland is so British in nature, it’s even called the Shire. They prefer comfort and predictability and tend toward stoutness. Bilbo Baggins, the only son of wealthy parents has settled into a very predictable and very comfortable middle-age. When Gandalf, a wizard known fondly for magnificent fireworks and less fondly for occasionally leading young hobbits off on some adventure, appears at his doorstep, Bilbo’s life takes a drastic turn. The wizard has come to bring Bilbo on an adventure. Despite the hobbit’s denial of any interest in such an undertaking, Gandalf leaves a mark on his door so a throng of dwarves can find their way their the next day.

The dwarves, led by Thorin Oakenshield, are survivors of the Lonely Mountain. Once a mighty and wealthy dwarven stronghold, one hundred and seventy one years earlier, it was sacked by the great dragon Smaug and its citizens killed or driven out. Save Thorin and one other, the dwarves are miners and smiths, not fighters. Still, the band is determined to reclaim their mountain and their treasure, despite having neither a plan nor the means to remove the dragon.

Succumbing to a repressed ancestral taste for adventure, Bilbo joins the dwarven company on its quest. Soon, Bilbo finds himself on the wrong side of hungry trolls, angry goblins, and, perhaps worst of all, Gollum.

Deep down here by the dark water lived old Gollum, a small slimy creature. I don’t know where he came from, nor who or what he was. He was Gollum—as dark as darkness, except for two big round pale eyes in his thin face. He had a little boat, and he rowed about quite quietly on the lake; for lake it was, wide and deep and deadly cold. He paddled it with large feet dangling over the side, but never a ripple did he make. Not he. He was looking out of his pale lamp-like eyes for blind fish, which he grabbed with his long fingers as quick as thinking. He liked meat too. Goblin he thought good, when he could get it; but he took care they never found him out. He just throttled them from behind, if they ever came down alone anywhere near the edge of the water, while he was prowling about. They very seldom did, for they had a feeling that something unpleasant was lurking down there, down at the very roots of the mountain. They had come on the lake, when they were tunnelling down long ago, and they found they could go no further; so there their road ended in that direction, and there was no reason to go that way—unless the Great Goblin sent them. Sometimes he took a fancy for fish from the lake, and sometimes neither goblin nor fish came back.

Just prior to his encounter with Gollum, Bilbo finds a plain golden ring, a Ring that will come to prove of vital importance in later years. After discovering it turns its wearer invisible, Bilbo uses it to his advantage to escape from the goblins, and to save the dwarves on several occasions, once from giant spiders and once from elven prison cells. Eventually, he even uses it to allow himself to engage in some dangerous banter with the dragon.

“Well, thief! I smell you and I feel your air. I hear your breath. Come along! Help yourself again, there is plenty and to spare!”

But Bilbo was not quite so unlearned in dragon-lore as all that, and if Smaug hoped to get him to come nearer so easily he was disappointed. “No thank you, O Smaug the Tremendous!” he replied.

“I did not come for presents. I only wished to have a look at you and see if you were truly as great as tales say. I did not believe them.”

“Do you now?” said the dragon somewhat flattered, even though he did not believe a word of it.

“Truly songs and tales fall utterly short of the reality, O Smaug the Chiefest and Greatest of Calamities,” replied Bilbo.

“You have nice manners for a thief and a liar,” said the dragon. “You seem familiar with my name, but I don’t seem to remember smelling you before. Who are you and where do you come from, may I ask?”

“You may indeed! I come from under the hill, and under the hills and over the hills my paths led. And through the air. I am he that walks unseen.”

“So I can well believe,” said Smaug, “but that is hardly your usual name.”

“I am the clue-finder, the web-cutter, the stinging fly. I was chosen for the lucky number.”

“Lovely titles!” sneered the dragon. “But lucky numbers don’t always come off.”

“I am he that buries his friends alive and drowns them and draws them alive again from the water. I came from the end of a bag, but no bag went over me.”

“These don’t sound so creditable,” scoffed Smaug. “I am the friend of bears and the guest of eagles. I am Ringwinner and Luckwearer; and I am Barrel-rider,” went on Bilbo beginning to be pleased with his riddling.

“That’s better!” said Smaug. “But don’t let your imagination run away with you!”

By hands other than their own, the dwarves find themselves rid of the dragon. This leaves them in control of the mountain and the treasure. Part of the treasure, though, is sought, not unreasonably, by the dragon’s slayer, among others. Dwarves, being dwarves — “dwarves are not heroes, but calculating folk with a great idea of the value of money” — have no intention of giving up one farthing of their hoard, and soon the stage is set for a great battle. Bilbo makes it home, but only after having to commit an act of great moral bravery. The hobbit who returns home is not the same as the one who left, which of course, will turn out to be of the greatest importance for Middle-earth in the years to come.

The first and best adaptation I’m familiar with is the audio version performed by Nicol Williamson for Argo Records in 1974. Lasting nearly four hours, it has the room to tell most of the story. I remember my mother bringing it home from the library and realizing how long and complete it was. I listened to all of it on a Saturday and loved every minute of it.

Williamson himself did many of the edits, removing the most of the ‘he saids.’ He used various regional UK accents to differentiate the various characters. Williamson was one of the great stage actors of the last century, possessed of an absolutely magnificent and captivating voice. I haven’t listened to all of Andy Serkis’ unabridged presentation of the book, but as good as what I’ve heard is, Williamson’s is still the winner. Here’s Part Two of Williamson’s version, starting with Bilbo’s encounter with a wonderfully ghastly sounding Gollum.

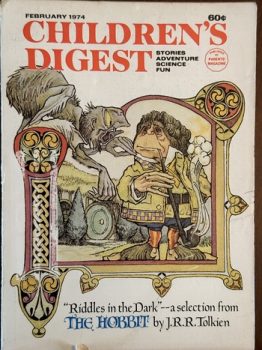

The video clip above of Bilbo and Smaug in the summary is from the second adaptation, the 1977 Rankin and Bass animated The Hobbit. The character designs were by Lester Abrams who had illustrated the Bilbo-Gollum confrontation for Children’s Digest. Arthur Rankin had seent he illustrations and liked them enough to engage Abrams for the movie. The animation was done by the Japanese company Topcraft (which would later go on to do Miyazaki’s first movie, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and become part of the foundation of Studio Ghibli).

The video clip above of Bilbo and Smaug in the summary is from the second adaptation, the 1977 Rankin and Bass animated The Hobbit. The character designs were by Lester Abrams who had illustrated the Bilbo-Gollum confrontation for Children’s Digest. Arthur Rankin had seent he illustrations and liked them enough to engage Abrams for the movie. The animation was done by the Japanese company Topcraft (which would later go on to do Miyazaki’s first movie, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and become part of the foundation of Studio Ghibli).

I love the movie, despite its too-rapid pace, the elimination of Beorn, and overall simplification. The painted scenery and backgrounds are wonderful, presenting Middle-earth in warm, muted colors. It looks at once realistic and fantastic. The voice acting, if not of Williamson’s caliber, is first-class, with Orson Bean as Bilbo, John Huston as Gandalf, Hans Conreid as Thorin, and, most wonderfully, Brother Theodore as Gollum.

Map of Wilderland by JRR Tolkien

Map of Wilderland by JRR Tolkien

It’s far from perfect, but it succeeds better than anything else at conveying a sense of real wonder with each new encounter Bilbo has with the increasingly strange and dangerous denizens of the Wilderlands east of the Shire. Rankin had declared that there would be nothing in the movie that wasn’t in the book, and he proved largely true to his word. It also makes good use of Tolkien’s songs. I admit to not loving Tolkien’s songs and poetry in The Lord of the Rings, but in The Hobbit, he provides some solid children’s poetry and it carries over well in the film. That it remains a children’s film and not some tarted up action movie is its greatest strength. Bilbo is a likeable and brave, and the scary bits are just scary enough for young viewers. At 78 minutes, it’s also the perfect length to get exposed to Middle-earth and JRR Tolkien.

I haven’t much to say about Peter Jackson’s three, interminable, cacophonous movies save “I give up!” I feel like I watched them for penance for any and all sins I’ve ever committed and will yet commit. Martin Freeman is fine enough, if far too thin, as Bilbo, but everything else is awful. Instead of the episodic charm of JRR Tolkien’s actual book, Jackson delivered three movies totaling nearly eight hours of sodden, CGI-infested stuff, packed full of things JRR Tolkien could never have conceived of.

Like with his LOTR trilogy, the films diverge from their sources the further they move along. While the first, An Unexpected Journey (2012), largely follows the form and shape of the book, the second, The Desolation of Smaug (2013), adds an unbelievably poor romantic entanglement and hints of municipal corruption in Lake Town. The dwarves Rube Goldberg plan to encase Smaug in molten gold had me wishing I had more hair to pull out of my head. By the third chapter, The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), all bets are apparently off. Even though I hate Jackson’s desire to turn the the titular battle into a gigantic spectacle, I understand it. The shenanigans of the the Master of Lake Town, however, are awful and nothing anybody who’s at all interested in the fate of Bilbo and the dwarves will be at all interested watching.

Oh, and I haven’t mentioned the terrible-looking and slog that is Gandalf and the White Council’s battle with the Necromancer, aka Sauron. No more than a plot device to extract Gandalf from the story, Jackson turned it into a great, big thing. It was fun to imagine just what happened while reading the book, but on the screen, it’s just one more great big distraction from what should be the only focus — Bilbo and the dwarves. And bird crap-covered Radagast and his bunny-draw sledge is stupid.

The great thing about the Jackson’s movies is that you don’t have to watch them if you want some sort of theatrical presentation of The Hobbit. Just go listen to Williamson (or Serkis, if you prefer) or watch the Rankin and Bass. Both are clearly works of love and respect for JRR Tolkien’s actual book and almost as much fun as reading the book itself.

Next month, I think it’s a time for something special; a visit to the Harvard Lampoon’s tremendously funny and offensive parody (and excellent pastiche) of Lord of the Rings, the Harvard Lampoon’s 1969 Bored of the Rings.

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part One

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Two – The Fellowship of the Ring by JRR Tolkien

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Three — The Two Towers by JRR Tolkien

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Four — The Return of the King by JRR Tolkien

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Sunday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him

You Can’t Handle the Tooth, Part II

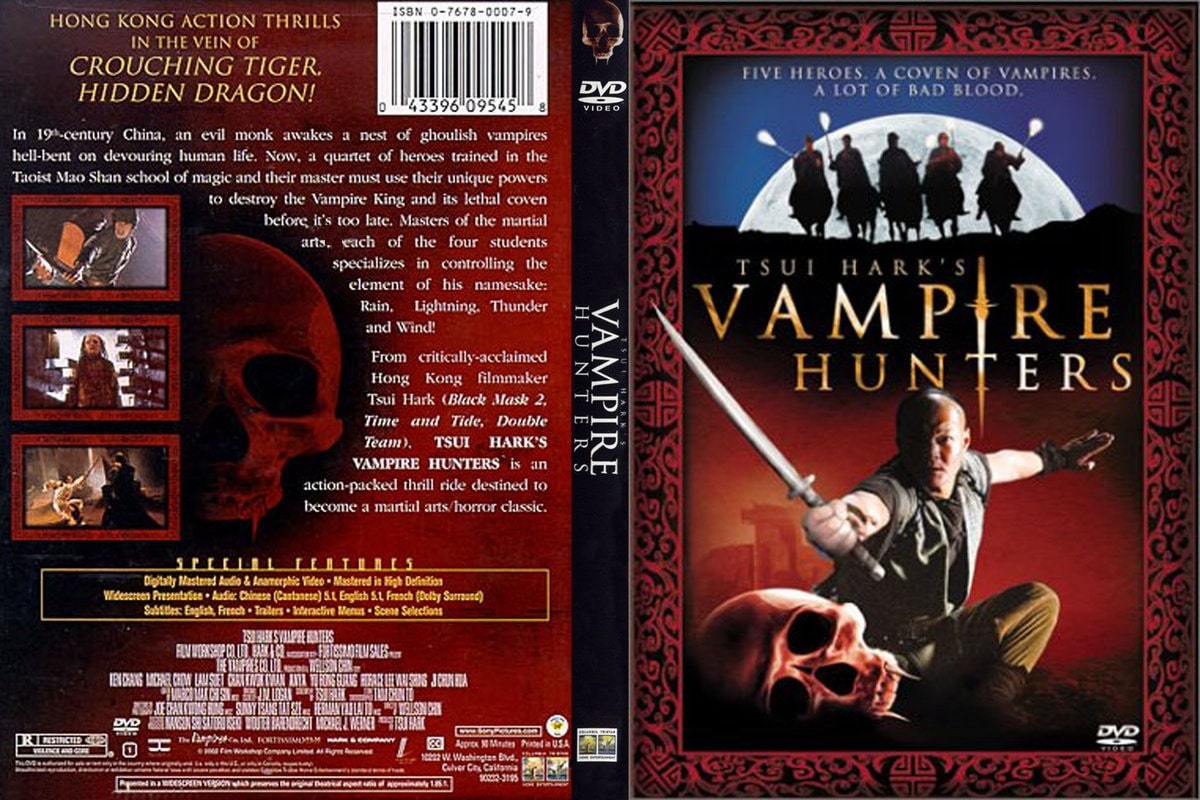

Tsui Hark’s Vampire Hunters (Film Workshop, 2002)

Tsui Hark’s Vampire Hunters (Film Workshop, 2002)

20 vampire films, all first time watches for me.

Come on — sink ’em in.

Tsui Hark’s Vampire Hunters (AKA The Era of Vampires) (2002) – PrimeThe original title is Era of Vampires, but for the North American release we end up with a spectacular bit of bait and switch trickery. Anyone who knows Tsui Hark’s work would be excited, after all, he gave us Zu Warriors from the Magic Mountain and the Once Upon a Time in China series — but we have been fooled. He produced this film, and wrote the story, but the director is Wellson Chin, better known for romantic comedies. For those of you who don’t know what this means, imagine going to see Steven Spielberg’s Jaws: The Legend Returns, and it’s directed by McG.

Anyhoo — the story is a simple one. Four Shaolin monks and their master have trained to locate and defeat vampires, but the first one they find manages to fend off 20 warriors and make the master go missing. The four (Rain, Wind, Lightening and Thunder) have a compass that points to vampire activity, and they track one to a wedding party. They infiltrate the home as party workers and try to find the monster. While all this is going on, there’s a separate band of robbers who want to find some hidden gold in the same domicile, the bride’s husband is killed, and the homeowner is covering any corpse he can find in wax. Naturally, threads and heads butt and much wire-work ensues.

The issue with this one is Chin really isn’t a very good action director. His shots are confusing and too close to the camera, and ultimately unsatisfying. There are some bonkers ideas, and the interaction between the monks is great, but overall it’s a bit weak.

One major highlight is the vampire itself — so nice to have a bloodsucker that can take on a gaggle of warriors instead of being easily staked by a surly teenager.

Check it out if you’re curious.

5/10

Vampie: The Silliest Vampire Movie Ever Made (Beautiful Rebellion Films,

February 14, 2014) and Black as Night (Amazon Studios, October 1, 2021)

Note, ‘Vampie’ is pronounced ‘Vam Pie’ as in ‘Meat Pie’.

I think we need to discuss the definition of ‘silly.’ When I think silly vampire movie, I think Mel Brooks’ Dracula: Dead and Loving It, or even Polanski’s Fearless Vampire Killers. A better alternative title for this one might have been Vampie: Mildly Amusing in One or Two Scenes. The rest of the time it’s a bit of a slog, hampered by a dodgy script and stilted line delivery. This is a shame, as writer/producer/star Ming Ballard and director Melissa Tracy have a potentially interesting concept, but not the chops (or budget) to make it work.

The story concerns Azure (Ballard), a centuries-old vampire who is allergic to blood. She runs a pastry shop with two friends, Tippy (Eric Strong), and Grace (Maya Merker, the highlight of the film).

Azure has a supernatural recipe item for a magical pie that she eats to stave off her blood hunger. When the pie ingredient is stolen by a rival vampire, she must get it back with the help of a Vatican assassin. That’s the plot in a nutshell.

Along the way, we get prolonged scenes of unfunny dialogue, unfunny flashbacks and a foul-mouthed chihuahua called Van Helsing. There are some moments of drama that are quite effective, but it was ultimately a chore to get through. Oh well.

4/10

Black as Night (2021) – PrimeHigh-schooler Shauna (Asjha Cooper, excellent), informs us via voiceover that what we are about witness is a crazy summer, one in which she got breasts, and killed vampires. This is no throwaway line in either respect. Shauna is 15 and riddled with anxiety, not only due to her own development, but the darkness of her skin (not helped by her brother who calls her Wesley Snipes in a wig), and her crush that she is too shy to talk to.

It’s a good way to start a film as her arc is clearly defined, but the main focus is shared between the vampires who prey on the homeless and addicted, and the after effects of Katrina, which continue to suck the very life out of the residents of this area of New Orleans. Part of the backdrop is The Ombreux, a rundown housing project that is home to junkies and the disenfranchised. This put me in mind of the Cabrini-Green inspired projects of Candyman, another film that explored the plight of black citizens framed with horror themes.

Many topics are explored in Black as Night through dialogue and one impressive speech by David Keith that touch on racism, gentrification, slavery and poverty, and these heavy issues are balanced with a frothy, Buffyesque romp featuring Shauna and her gang (best gay friend Pedro, crush Chris and vamp lit boff Granya). Moments actually put me in mind of Fright Night (inexperienced youths enter a forbidding mansion to kill bloodsuckers) and I enjoyed myself.

It’s not all great though, one villain was woefully underused, the narration started to outstay its welcome, and the actual horror was a bit lackluster, but overall, a solid film from director Maritte Lee Go, and I’m interested to see what she gets up to next.

7/10

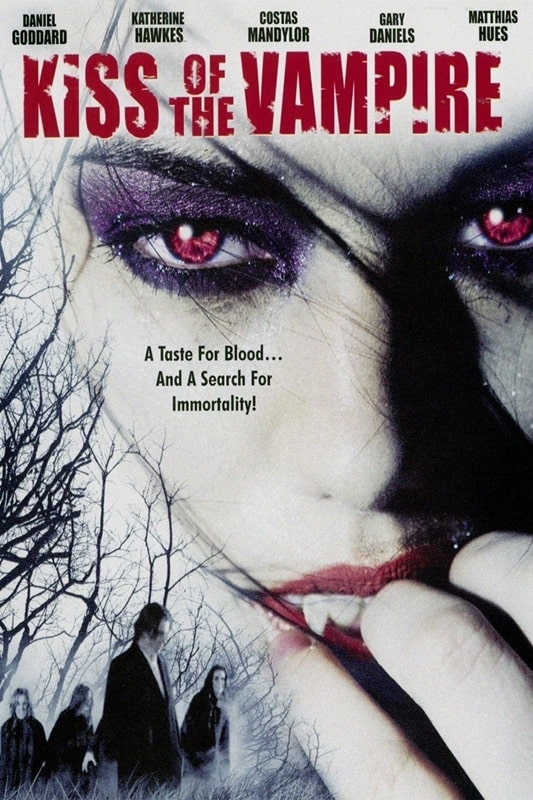

Kiss of the Vampire (Immortally Yours, January 6, 2009) and Renfield (Universal Pictures, April 14, 2023)

Ugh — we reach the halfway point and I want to chew my leg off.

I’ve stated before that I try not to rag too much on bad films, because I know first-hand how hard it is to make one (good or bad), but this one just annoyed the hell out of me. Despite having enough in their budget to lob a couple of thousand at Costas Mandylor (Saw series) and Martin Kove (everything else), the rest of the budget must have gone on craft services, because it definitely didn’t get spent anywhere else.

Especially not on sound. Scenes are barren and poorly miked, and the costumes came straight from Ruby’s Halloween bargain bin. The effects are tragic, the acting lacklustre and the story is nonsensical. I’m sure the actors were told they were making an epic based on Twilight and Underworld, with the Illuminati thrown in, but they ended up in a convoluted mish-mash of ideas, none of them concluded satisfactorily.

Avoid.

Or watch, if you’re full of self-loathing.

2/10

Renfield (2023) – PrimeA lesson to be learned here about getting your hopes up. I was pretty excited to see this one, as I desperately want Universal to have a hit (The Invisible Man is the only one they haven’t screwed up), and I love Nicholas Hoult, Nic Cage and Awkwafina (to a degree).

I knew going in that the tone would be irreverent, but I had no idea how slapstick they were going to go with the horror (an impressive blend of practical and CG), or that Cage was going to portray Dracula as if he was in Carry On Count.

I thought the concept was excellent (if a little flimsy), however I would have really dug a film closer in tone to Ready or Not or Werewolves Within. Everyone just needed to dial the lampooning down two notches. Ah well.

7/10

Vampires vs. The Bronx (Netflix, October 2, 2020) and I Like Bats (Zespół Filmowy, 1985)

Zoe Saldana is listed in the opening credits, and is gone after 2 minutes. Hey, it’s a good name to bait investors with, so fair play to them.

Vampires vs. The Bronx brings nothing new to the table, it evokes the kids vs monsters theme of Attack the Block and Lost Boys (even emulating Greg Cannom’s Lost Boys vampire makeup), makes several references to Blade (and copies its gnarly deaths), and is littered with in jokes (the realtor firm is called ‘Murnau’, and their logo is Vlad himself).

It might be derivative, but it also skips along at a fair old pace, helped by a charismatic group of child actors and a tongue-in-cheek script. The vampire front is a realtor company (headed by Shea ‘Skull Island’ Whigham) and the metaphors fly thick and fast as the Bronx rapidly succumbs to the soul-sucking practices of gentrification.

It’s fun, horror-lite, gateway fare for younger viewers who might be vamp-curious, and one of the few Netflix productions that doesn’t rely on green and purple gels. Worth a look if you’ve got a spare 90 mins.

7/10

I Like Bats (Lubię nietoperze) (1985) – PrimeIt’s off to Poland now, for a strange little film that can’t quite settle on a genre or tone. It’s a game of two halves, the first being the infinitely better one, but we’ll get to that.

Katarzyna Walter is Izabela, a vampire whose raison d’être seems to be ridding the world of scumbag men. General creeps, stalkers, would-be rapists, and murderers are first seduced and then sucked dry by Iza, whose overbearing aunt persistently complains about the lack of men in her life.

I enjoyed this half — with Iza in the role of avenging angel. It’s moody, gothic and beautifully shot. It also feels timeless — scenes of the contemporary town could be from decades before the mid-80s, and some clothing and vehicles feel anachronistic, but one character mentions AIDS, and we are jolted back to the correct setting.

The second half of the film is where things go awry. Iza checks herself into a psychiatric hospital in an effort to become human because she has fallen in love with the head doctor. They don’t believe her of course, however, she can’t be hypnotized or x-rayed and is soon biting the workers (her first victim is the lothario gardener who shags all the nurses in the tomato house). Then, all of a sudden, Iza is settled in domestic bliss. And that’s it.

A bit of a curio, recommended for certain types. Not saying who.

5/10

Previous Murky Movie surveys from Neil Baker include:

You Can’t Handle the Tooth, Part I

Tubi Dive

What Possessed You?

Fan of the Cave Bear

There, Wolves

What a Croc

Prehistrionics

Jumping the Shark

Alien Overlords

Biggus Footus

I Like Big Bugs and I Cannot Lie

The Weird, Weird West

Warrior Women Watch-a-thon

Neil Baker’s last article for us was Part I of You Can’t Handle the Tooth. Neil spends his days watching dodgy movies, most of them terrible, in the hope that you might be inspired to watch them too. He is often asked why he doesn’t watch ‘proper’ films, and he honestly doesn’t have a good answer. He is an author, illustrator, teacher, and sculptor of turtle exhibits. (AprilMoonBooks.com).

The Remarkable 4 Books of Pellinor by Alison Croggon

Reviewer Emmie Finch on the books of Pellinor, by Alison Croggon. Pellinor – The Naming,…

The post The Remarkable 4 Books of Pellinor by Alison Croggon appeared first on LitStack.

Blog Update and Substack

Hi, everyone

As you may have noticed, I have been having some problems with this blog. My antivirus software keeps sending alerts, suggesting a phishing scam, and I am not the only one having these problems. The helpdesk insists there is nothing wrong on their end, and while I have reported it to Norton as a false positive so far they haven’t cleared it or confirmed what is actually wrong. I’ve only been able to get into the blog through iPad, which isn’t much good for editing, and the WordPress app.

I’m hoping to get this problem fixed, but so far no luck.

Accordingly, I have opened a Substack (link below) and I have tried to transfer the mailing list from the blog to Substack. Hopefully, if you were subscribed, you should be able to receive emails from Substack without any further problems. If you weren’t subscribed, please take this opportunity to sign up.

https://chrisnuttall.substack.com/

I need to say at this point that I cannot guarantee any paid-subscribers content only. I don’t feel confident in my ability to maintain a steady stream of posting to justify charging access – I have thought about offering draft chapters to subscribers, but they won’t have been edited let alone fixed, so I’m reluctant to do it. If you do take a paid subscription, you are supporting me but you are not necessarily getting anything in return.

(On the plus side, you will help keep me writing.)

Depending on what happens, I may try to keep this blog updated. I still get comments via email even if I can’t see them on the browser. However, I have no idea how that will work out.

Thank you for your time, and I hope to see you on my new Substack.

Christopher Nuttall

PS – upcoming …

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #37: Corporations (I) by Kevin

You know it’s a really good sign that a typically boring entities such as a corporation is really interesting and informative when Drucraft is involved! Can’t wait to see next’s week on The United States and presumably other countries or international Megacorps!

Quick question both here and in Book One there have been mentioned of factions in the US and the UK Board, are they as organized as the Light Council factions in Alex Verus? Or are they more informal such as specific Houses or Corporations being aligned on an issue that effect how the sell their sigls?

The Inheritance: The Rest of Chapter 7

I crouched on a narrow stone ledge protruding above a vast cavern. Bear lay next to me gnawing on a stalker femur.

Long veins of luminescent crystal split the ceiling here and there and slid up the walls, glowing like overpowered lamps, diluting the darkness to a gentle twilight. My talent told me it was Fos stone, a breach mineral that shone like a flashlight. The biggest Fos stone I had seen until now was about the size of my fist.

Two hundred and sixty-two feet below us, at the bottom of the cavern, enormous lianas climbed the stone wall, bearing giant flowers. Each blossom, shaped like a twisted cornucopia, sported a funnel at least ten feet across and fifteen feet deep, fringed by thick, persimmon-colored petals that glowed weakly with coral and yellow. It was as if a garden-variety trumpet vine had been thrown into the chasm and mutated out of control into a monstrous version of itself.

Strange beings moved along the cavern floor, clad in diaphanous pale robes. Their torsos seemed almost humanoid, but there was something oddly insectoid about their movements. They strode between the flowers, carrying long staves and pushing carts.

As I watched, one of them stopped at the opposite wall far below and tugged on the long green tendrils dripping from a large blossom. A spider the size of a small car slid from the flower. It was white and translucent, as if made of frosted glass.

The being checked it over, prodding it with a staff topped with a large chunk of colored glass or maybe a huge jewel. My talent couldn’t identify it from this distance. The spider waited like a docile pet.

The being dipped a slender appendage into their cart, pulled out a glowing fuzzy sphere that looked like a giant dandelion, and tossed it to the spider. The monster arachnid caught it and slipped back into its flower.

The spider herder moved on to the next blossom.

It was surreal. I’d been watching them for about two hours and my mind still refused to come to terms with it. There were hundreds of flowers down there, and most of them held spiders. The herders had been clearly doing this for a long time – their movements were measured and routine, and they had made paths in the faintly glowing lichens sheathing the bottom of the cavern.

I was watching an alien civilization tend to its livestock.

“Do you know what this is, Bear? This is animal husbandry.”

Bear didn’t seem impressed.

If I had to herd spiders, this would certainly be a good place. From this angle, the cavern looked almost like a canyon, relatively narrow with steep, mostly sheer walls. They had a water source – the narrow ribbon of a shallow stream twisted along the cavern’s floor. I couldn’t see any other entrances, although there had to be some, probably far to the left, behind the cavern’s bend. If stalkers or other predators somehow invaded, they would be easy to bottleneck. It was an ideal, sheltered location except for one thing.

Another spider herder emerged from behind the bend on the left. My ledge ended only a few feet away on that side so I couldn’t quite see where they came from. This one was pushing a larger cart.

“Here we go,” I murmured to the Bear.

She flicked her ear.

The spider herder paused. Above them, about forty feet off the ground, a large blossom glowed with gold instead of red. The being raised their staff and leaped at the wall, clearing ten feet in a single jump. The spider herder climbed up the vine, shockingly fast, reached the flower, and thrust the staff into the blossom.

I glanced to the right. Across the cavern, a fissure split the wall near the ceiling, a crack in the solid stone about eight feet tall and five feet across at its widest.

Nothing moved. The fissure remained dark.

The spider herder swirled the staff as if scraping the pancake batter out of a bowl.

The fissure stayed still.

The spider herder pulled his staff out. Three dense clumps of spider silk hung suspended from the staff, glowing softly with cream-colored light. They were about the size of a beach ball.

A segmented body squeezed out of the fissure and dove, three pairs of translucent wings snapping open in flight. A wasp-like insect the size of a kayak zipped through the air, glinting with blue and yellow like a blue sapphire wrapped in gold filigree.

Bear jumped up and growled.

The spider herder saw the wasp and scrambled down, but not quickly enough. The giant insect divebombed across the cavern, hooked one of the spider eggs with its segmented legs, tearing it from the bundle, and shot up, buzzing along the wall into a U-turn. A moment and it squeezed back into the fissure, taking its prize with it.

The spider herder stared after it for a long moment, climbed down, and deposited the two remaining egg sacks into their cart.

I had seen a similar scenario play out hours ago, when I first found the cavern. I had backtracked since then, exploring as many of the tunnels around it as I could. All of them either dead-ended or led to a narrow, bottomless chasm that ran parallel to this cave. I returned to the ledge a while ago and have been sitting here since, observing and deciding how to proceed.

I closed my eyes and concentrated. The anchor was still straight ahead and to the left of me, radiating discomfort. I opened my eyes. I was looking right at the bend of the cavern.

If we wanted to get to the anchor, we would have to pass through this underground canyon. There was no way around it. Backtracking wasn’t an option. We were truly lost at this point.

Unfortunately, I had a feeling that the spider herders wouldn’t welcome our intrusion into their territory.

Another wasp squeezed out of the gap and dove down, aiming for the cart. The spider herder let out a loud clicking sound. A green spider the size of a donkey raced around the bend of the cavern and leaped into the air, knocking the wasp into the wall. The insect and the arachnid tumbled down through the vines and rolled onto the floor. The wasp jabbed at the spider with a stinger the size of a sword, but the spider clung to it and sank its fangs into the wasp’s neck. The insect’s head fell to the ground.

The spider herder made another clicking noise. The green spider abandoned the wasp and scuttled over to the cart. The herder pulled out a glowing yellow globe and tossed it to the spider. The arachnid caught it and ran back around the bend.

“Look, Bear, your cousin from another dimension got a treat.”

Bear tilted her head.

The spider herder leveled their stave at the wasp’s body. A moment passed. A bolt of orange lightning tore out of the gem and struck the carcass. The insect sizzled and broke into dust.

The activation time was a bit long. The wasps would have no trouble evading, considering the delay it took to fire, but once the beam hit, the results were devastating.

If Bear and I strolled down there, assuming we somehow got down off the ledge, trying to make our way past the herders would be impossible. Between the green spiders and that orange lightning, we wouldn’t get through, not without some serious injuries.

I glanced at the fissure. There was a wasp nest behind it. Spiders were excellent wall climbers. Theoretically, the spider herders could mount a full assault against it, but there were three problems with that.

First, the fissure wasn’t wide enough. The wasps were long and narrow, and they folded their wings to get through. The white spiders would never fit. The green ones could try to squeeze in there, but they would have to enter one at a time, and the wasps would swarm them.

Second, the wasps could take flight if they detected the assault and simply wait it out. The spiders couldn’t sit by that wasp nest indefinitely, and waiting by it exposed them to the aerial assault.

And third, the entirety of the wall around the nest was sheathed in mauve flowers. Toward the top, where my ledge met the fissure, the wall wasn’t strictly sheer. It broke down into a series of outcroppings, and the mauve flowers clung to the rocks like some deadly African violets. There was no way to approach the nest without going through them.

When one of the white spiders popped out of the highest flower, I had a chance to scan it. They were not immune to the pollen. It would short-circuit their nervous system. The spider herders and the wasps were at a standoff.

When I first stumbled onto the cavern, I got another vision. A group of three spider herders, their veils shifting in the wind of an alien world with a mass of giant spiders behind them; someone with human arms offering a carved wooden box to them; the leading spider herder accepting it; the spiders parting; and a single word spoken: Bekh-razz. A gift for the safe passage.

I would have to offer a gift to cross.

The spiders couldn’t get to the nest, but I could. The ledge I was on curved along the wall all the way to the nest. It was barely seven feet wide near the entrance to the hive. I wouldn’t have a lot of room to work with.

I got up and walked along the ledge toward the fissure.

Bear dropped her bone and trotted after me. I halted by the first clump of mauve blossoms and flexed.

They glowed with pale lilac. I split the glow into individual layers of light blue and pink. The blue told me they were still mildly toxic to both me and Bear, but nothing our regeneration wouldn’t take care of, and the faint pink let me know that if properly processed, the plant could be used as contact analgesic. Made sense. That’s why we didn’t notice the effect pollen had on us until it was too late.

The wasps displayed hive behavior. I didn’t need a vision to clear that up for me. It was obvious from their patterns. That meant that the moment I attacked the nest, every wasp would fight to the death to kill me. I had no idea how large that nest was. Or how many giant wasps waited inside. I had to be very sure, because once I started, there was no stopping. Earth wasps were vindictive, and it was safer to assume these would be, too. Even if I ran away, they would chase me through the caves and there was no passage narrow enough to lose them anywhere around this cave.

The nest rumbled.

I dropped to the ground. “Down.”

Bear hugged the ledge with me.

“Good girl,” I whispered.

A large wasp squeezed through the gap and took off, vanishing around the bend.

I wonder how they know when the eggs are harvested? Do the eggs emit a pulse or something…

A hoarse shriek echoed through the cavern. That was new.

The wasp zipped back toward the nest, carrying another silk-wrapped spider egg in its claws. The egg glowed with coral pink. I flexed, focusing on it, but the wasp was too fast. Half a blink, and it squeezed into the nest.

I’d seen them steal three eggs besides this one, and nobody screamed the first three times. Also, the rest of the eggs glowed with cream, not pink. There was something special about this egg.

This was my best chance. I had to act now or find a different way.

I flicked my wrist, elongating the cuff into a sharp, two-foot blade shaped like a machete. Bear let out a soft, excited whine.

“Shhh.”

I padded through the flowers, my dog trailing me.

This was a foolish plan.

Ten yards to the nest.

Five.

Three.

Something rumbled within the fissure.

I cleared the distance between me and the gap in a single jump.

A wasp thrust out of the gap. I swung the blade and lopped its head off. The blue and yellow body crashed down, and I grabbed it with my left hand, yanked it out of the fissure, and sent it flying to the ground far below.

Bear broke into barks. There goes our element of surprise.

The entire nest buzzed like a tornado spinning into life. Another wasp shot through the fissure, and I cleaved it in half, my sword cutting through the segmented thorax like it was butter.

#

“Sir?”

Elias’ eyes snapped open. Leo hovered in his view. Elias sat up.

“We found Jackson,” the XO said.

#

Two wasps tried to squeeze through the gap at the same time and got stuck one on top of the other. I twisted the sword into a spike, skewered the top one, because it was closer and let its dead weight push the second wasp down. It struggled, pinned to the ground, and I hacked at it.

The buzzing was deafening now. The walls of the fissure vibrated as the enraged hive mobilized for an all-out assault. Next to me Bear barked her head off, flinging spit into the air. She wasn’t just a dog, she was a guild K9, trained to alert when the breach monsters came near. The monsters were here, and she was alerting everyone.

I grabbed the body of the top wasp, pulled it out of the fissure, and hurled it over the edge.

#

“He’s been detained by the authorities in Japan.”

It took Elias a moment to process that tidbit. “On what pretext?”

“They claim he entered a luxury restaurant, ordered a high-quality cut of Wagyu beef, washed it down with Yamazaki Single Malt 55-Year-Old Whisky, which retails for 400K a bottle, and walked out without paying.”

“They’re saying he dined and dashed?”

Leo smiled. Technically, it was a smile, but it looked more like a predator baring his teeth.

#

Bodies clogged the fissure, drenched in hemolymph. I stabbed and hacked into the pile up, yanking chunks of the insects out.

Seven wasps.

Eight.

Twelve.

#

“Jackson? The vegetarian who drinks one beer a year and only under duress?”

“Yes, sir. Our Jackson.”

Elias hid a growl. It was a retaliation for Yosuke.

Two years ago, a star Void Ronin, a top tier Talent, had a falling out with the largest guild in Japan and quit. They blacklisted him. No other guild in the country would hire him. The idea was that the pressure of unemployment would force him to crawl back home. Yosuke called their bluff. Cold Chaos welcomed him into the fold eighteen months ago. He was enroute to Elmwood now from another gate and was due to arrive tomorrow.

Publicly, Hikari no Ryu said nothing. Privately, the guild wielded a lot of power in Japan, and they were pissed. Elias thought that they reached an understanding regarding this matter. Apparently, he was mistaken. It didn’t matter. Elias had never regretted the decision, and he wasn’t about to start now.

“Have they made any demands?” he asked.

“No. Most likely they will hold him and wait for us to come to them.”

Guild politics were convoluted and cutthroat. It didn’t matter which continent. Elias had dealt with worse nonsense stateside plenty of times. But there was an unspoken rule all guilds followed – healers were exempt from all of the political bullshit. They were off limits. You didn’t poach them, you didn’t threaten them, and you didn’t retaliate against them. They chose who they worked for, and if you got a good one, you did everything you could to keep them.

Someone in Japan had just crossed a very dangerous line.

“How would you like to proceed?” Leo asked.

“I’ll make some calls.”

#

The nest lay silent.

Bear was still barking.

“Quiet.”

The shepherd clamped her mouth shut. I listened for the buzzing.

Nothing.

“Stay, Bear. Stay. Stay!”

Bear sat down.

I’d killed twelve smaller wasps, probably workers, and five larger wasps, probably guards. Back home wasp colonies had a queen. She was usually larger than the workers and the guards, and if that held true here, she was trapped within the nest.

I slipped into the fissure, moving slowly and quietly. It was about ten feet deep. Beyond that, the passage widened into another cave chamber steeped in gloom and dappled with pools of pale light coming from above. I flexed. One hundred and twelve yards to the other wall. A lot of open space, and the floor was unnaturally clear. The wasps must’ve removed all of the debris that originally littered the chamber. Once I exited the fissure, I would be exposed.

A step.

Another.

A whisper of something large shifting its weight on the right, just outside the passageway. I had expected the wasp to strike from above, but it sounded like it was on the ground instead.

I stopped, poised on my toes. My fingers trembled. Fear filled me. I was overflowing with it.

Another faint whisper. The wasp was waiting just feet away, ready to ambush me the moment I entered. I had to rely on speed.

I darted into the nest, angling to the left. A shadow fell over me and I dove forward, rolled, and came back to my feet.

A massive wasp bore down on me. It was as big as a bus, riding on six huge, segmented legs, each armed with two chitin claws the size of sickles.

Crap.

The wasp charged me. It wasn’t flying. It ran across the floor, straight at me, swiping at me with its terrible claws. I darted back and forth like a terrified rabbit.

Right, left, left, too many fucking legs, right…

The wasp swiped at me like a hockey player armed with deadly scythes. It was trying to skewer me and drag me to its terrible mouth where two sets of sharp mandibles would shred the flesh off my bones and rip me apart.

The world shrank to the stone floor of the cavern, the pools of light, and the horrible creature behind me. All my instincts screamed in panic. I had to run away. I had to run from this thing back through the fissure, but I couldn’t find it. The walls were a dizzying whirlwind.

I was out of breath. I was disoriented. I couldn’t even think long enough to come up with a plan. All I could do was run for my life. Running wouldn’t work for too much longer. I would die here, in this nest.

Something dark and shaggy shot out of the wall. Before my brain processed what it was, Bear charged at the wasp.

“No! Bear, no!”

The German Shepherd clamped her jaws on one of the wasp’s middle legs. The insect shook it and flung Bear off.

“No!”

One of the wasp’s legs sliced like a scythe. I saw it coming. I had stopped running because of Bear and now it was too late. I jerked back, but not fast enough. The blow swept me off my feet. I rolled across the floor, pain smashing into my side. The wasp reared above me. Its front leg came down like a hammer. One of the two claws pierced my right thigh, scraping the bone.

Bear leaped out from the side and bit the leg impaling me. The wasp queen didn’t even notice. The other claw clamped on my other leg. The ragged chitin sank into my flesh. I felt myself being lifted, up to where the horrible mandibles clicked.

No.

I sliced at the wasp leg pinning me. My sword cut through chitin like it was a twig. The wasp recoiled. I yanked the severed stump out of my thigh and rolled to my feet.

Fuck this shit. Why the hell was I running?

Bear snarled next to me.

The wasp swiped at me with its uninjured front leg. It was huge and fast, but I was faster. I leaned out of the way. The leg carved through the spot where I had been. The wasp swiped again, and I stepped back again, just out of reach.

Strike, dodge. Strike, dodge. It couldn’t touch me.

I flexed, stretching time like a rubber band, forcing my senses into overdrive. The uninjured front leg struck at me, slow like molasses. I cut it, dashed under the wasp, severing the other legs with quick strikes as I sprinted past, and emerged behind the monster insect. A second and it was over. The world restarted, and the queen crashed to the floor, the stumps of her legs jerking in wild spasms.

Bear howled.

I took a running start and jumped. My leap carried me through the air, and I landed on the queen’s fat abdomen and dashed toward her head.

The queen’s huge wings stirred. It was trying to fly.

I slipped on the narrow waist connecting the abdomen and thorax, caught myself, leaped onto the thorax, and scrambled onto her neck.

The wings hummed and blurred like the blades of a helicopter. A gust of wind buffeted me.

I drove my sword into the queen’s neck. It sank through, and I ripped it to the side, carving through the exoskeleton. The queen’s head drooped, and I chopped at the thin filament connecting it to the body.

The head crashed down.

The wings kept going. The headless body rose in the air, carrying me with it. I clung to it. The wasp corpse climbed twenty feet up…

The wings slowed.

The body fell slowly, careened, and landed in a heap. I jumped, rolled to break my fall, and came up in a crouch.

The queen was dead.

#

Elias put away his phone.

“Nice.” Leo grinned.

“They wanted a fight. We gave them a fight.”

All they had to do now was wait.

The post The Inheritance: The Rest of Chapter 7 first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

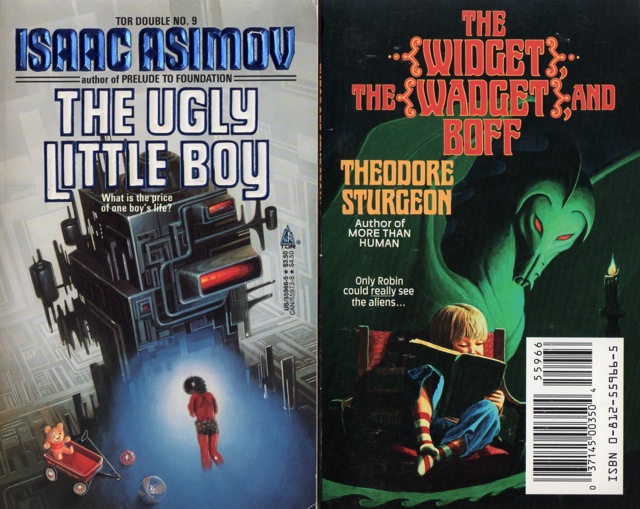

Tor Double #9: Isaac Asimov’s The Ugly LIttle Boy and Theodore Sturgeon’s The [Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff

Cover for The Ugly Little Boy by Alan Gutierrez

Cover for The Ugly Little Boy by Alan Gutierrez

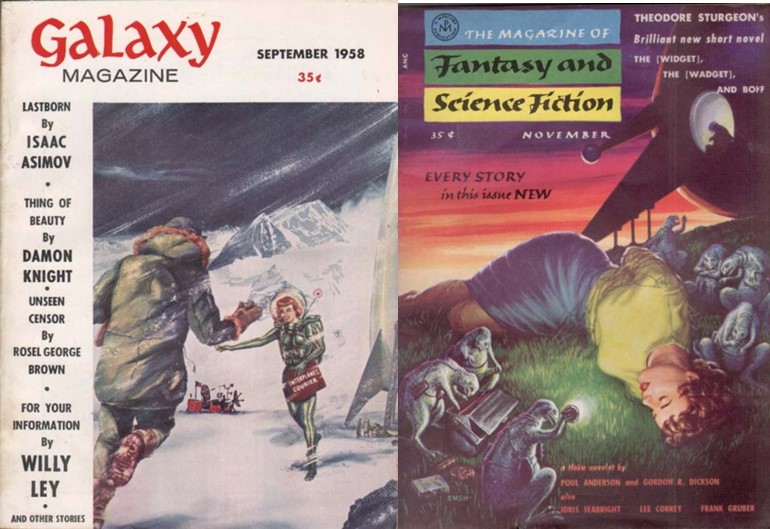

Cover for The [Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff by Carol RussoThe ninth Tor Double collects novellas by Isaac Asimov and Theodore Sturgeon, the only entries by either author. The Asimov’s story is The Ugly Little Boy and Sturgeon offers the oddly titled The [Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff. This volume is the first to include two stories that did not win, or even receive a nomination, for any awards. Leigh Brackett’s story in the previous volume wound up winning the 2020 Retro Hugo Award.

Theodore Sturgeon’s The [Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff was originally published in F&SF in November, 1955. The strange title is entirely fitting for the strange story Sturgeon has to tell. Just as two of the words in the title are framed by brackets, the story has a science fictional device framing it, in the form of a report by two aliens visiting Earth. In their report, which partly looks at whether or not “Synapse Beta sub Sixteen” exists in humans (and whether the species can survive without it), but also serves as an indictment of one of aliens by the other, the aliens set words in brackets when there is no exact English equivalent for what they are attempting to say.

The story framed by this conceit could have been published in any of the mainstream magazines. It tells the story of the residents of a boarding house in a small town. Bitty and Sam Bittelman run the house, which has gathered its fair share of misfits. Tony O’Banion is a successful lawyer whose privileged upbringing gets in his way, Mary Haunt is a movie star wannabee who is waiting for her break, Phil Halvorson has undefined issues, but seems to be either gay or asexual in a world which sees both as a perversion, Miss Schmidt is a school librarian who keeps to herself, and Sue Martin is a hostess in a nightclub. Sue’s three-year-old son, Robin, creates a connection between the characters.

Robin is an easy going child, whose happiness with the world around him causes most of the residents of the boarding house to adopt him. When his mother is sleeping during the day, the Bittelman watch over him. If they aren’t available, “Tonio Banion” tries to make time for him, taking him along of visits to a local amusement park where O’Banion provides legal services. Miss Schmidt cares for him at night when Sue Martin is at work.

Although Robin is not a view-point character in the story, Sturgeon does an excellent job of presenting his world view, from his mishearing O’Banion’s name as Tonio to his anthropomorphizing of kitchen appliances, such as Mitster (a mixer) or Washeen (the washing machine). Robin also has two imaginary friends, the titular Boff and Googie.

As the story progresses, Sturgeon’s focus on the residents of the boarding house slowly builds up the complexity of their relationships and personal problems. Many of the characters receive a spotlight, either as Sturgeon explores their activities or inner thoughts or when they have conversations with Bitty or Sam, both of whom have a tendency to ask probing questions of their boarders that make them reconsider their lives and choices. At the same time, Bitty and Sam are never shown as prying or anything less than nurturing.

The result is that even as their boarders begin to come to terms with the realities of their existence, either dreams that cannot be attained or the manner in which they are standing in the way of the own success, the story starts to feel more hopeful. Once their issues are realized, they are more likely to be able to take care of them. Throughout the story, reports from the two aliens who are watching them also continue to play a role, giving the indication that the growth of the individuals is caused, at least in part, by the “Synapse Beta sub Sixteen” the aliens are looking out for.

Boff and Googie are woven throughout the story, and while Robin is always aware of their activities and location, as imaginary friends, they are either dismissed or patronized by the adults in the story. The reader, aware that Boff’s name appears in the stories title, realizes that there is an importance to the characters and the manner in which the nature of Robin’s imaginary friends is revealed is clever and ties in quite well to his way of seeing the world through the eyes of a three year old.

Even if the revelations each of the characters have about themselves in response to the Bettelman’s questions can’t be considered a happy ending, each of the characters appear to be in a healthier place when the story ends, having come to terms with their position in life and finding a way to continue further in a way which will not leave them more damaged than they were at the beginning of the story.

Galaxy Magazine September 1958 cover by Dember

Galaxy Magazine September 1958 cover by DemberThe Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction November 1955 cover by Ed Emshwiller

The Ugly Little Boy was originally published as “Lastborn” in Galaxy in September, 1958. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award, winning the latter. In 1991, Robert Silverberg would publish an expanded, novel length version of the story, retitled Child of Time (although the American version of the novel would retain the title The Ugly Little Boy.

Just as three-year-old Robin is to center of The [Widget], The [Wadget] and the Boff, the titular boy in Asimov’s story is also three years old when his story begins, or at least in the flashback that shows how he got into the situation the story covers.

Edith Ffellowes is a nurse who has been hired by a company called Stasis, Inc. under the assumption that their first experiment, to bring a Homo neanderthalensis to the contemporary period. The CEO of Stasis, Inc., Gerald Hoskins, hires Ffellowes after a cursory interview in which he is mostly concerned over whether she loves all children or just pretty children. It isn’t until she shows up for the attempt to retrieve the child that she begins to understand the actual details of the job for which she has been hired.

Although Ffellowes is taken aback by the boy’s appearance when she shows up, she is a professional and works to take care of him, cleaning him up and attempting to engage with him despite the language barrier. By bringing a three year old rather than an adult, Asimov is able to ignore the cultural issues which would have arrived by bringing in a fully functioning member of Neanderthal society. It also gives him the opportunity to have Ffellowes attempt to educate the boy, who she names Timmie in a failed attempt to stop the press from referring to him as an ape-boy.

The primary purpose of Stasis, Inc’s, experiment was to bring a living creature from the Neanderthal period to the modern time, and they succeeded. The secondary purpose was to learn about Neanderthal culture and physiology. Although the latter was possible from their experiment, a three-year-old will not be able to teach them much, especially one who’s culture is infected by the teachings of a modern woman.

As the story progresses, Ffellowes works to socialize Timmie, including asking Hoskins to allow him to interact with a modern human boy of the same age. Although the initial meeting between Timmie and Hoskins’ own son, Jerry, does not initially go well, eventually the two build up a friendship of sorts, although there is always an undercurrent of tension brought on due to the differences between the boys and Hoskins’ own attitude toward Timmie. Although he generally says the right things to Ffellowes about her charge, he occasionally indicates that he sees Timmie a less than human.

Asimov’s focus with the story is on Ffellowes and the relationship she builds up with Timmie. Even as the world sees him as an ape-boy, she fights for his dignity and to teach him how to be a person. Asimov’s is less interested in the impact their relationship has on Timmie’s way of thinking, taking the point of view that there is no difference between a three year old Neanderthal and a three year old human are essentially the same, except for their physical appearance.

He also doesn’t seem to be overly interested in the ethics of Hoskins’ experiment. Hoskins’ questionable scientific ethics are apparent from the beginning, when he hires Ffellowes with only the briefest of interviews and without providing her with the information that she would need to make an informed decision. Throughout the experiment, he shows little more interest in Timmie than he does in the inorganic material Stasis also brings through, eventually attempting a similar experiment with a fourteenth century Italian, demonstrating that from an ethical point of view the company has learned nothing.

Written in Asimov’s clear style, it is similarly clear why Robert Silverberg expanded the story into a novel 34 years after its initial publication. The story is overly simplistic, offering hints and weighty issues that it could address. Similarly the understanding of Neanderthal culture advanced in the intervening years. Silverberg’s focus was more on the Neanderthal period than the ethical concerns regarding Hoskins and Stasis, Inc.’s methodology.

The cover for The Ugly Little Boy was painted by Alan Gutierrez. The cover for The [Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff was painted by Carol Russo.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

COVER REVEAL: Liminal Monster by Luke Tarzian

Preorder Liminal Monster over HERE

Add Liminal Monster on Goodreads

Luke Tarzian has graced us with the cover for this newest story titled LIMINAL MONSTER. Firstly here's the blurb for it

Plus here's the snazzy cover for it which has been created by the author himself

For those reviewers who might be interested to review it, the author has set up an e-ARC request form over here.

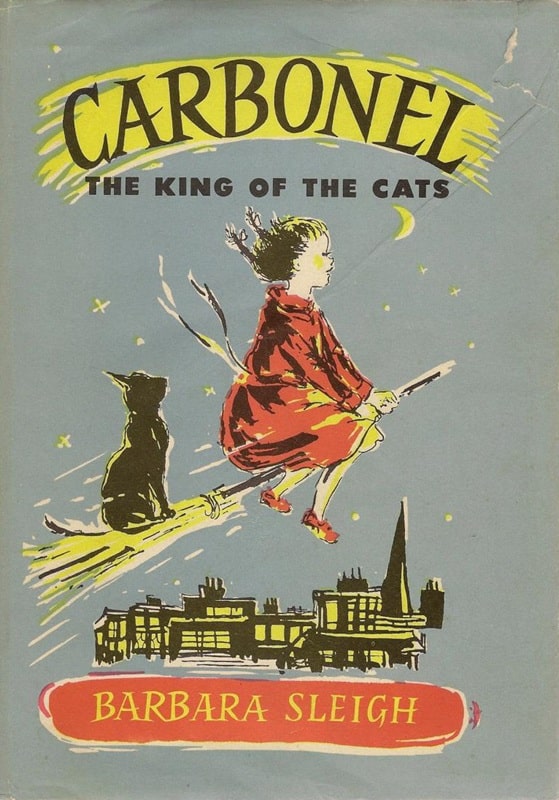

A Kind Heart and the Right Sort of Hands: Carbonel, the King of the Cats by Barbara Sleigh

Carbonel the King of the Cats by Barbara Sleigh (Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1957). Illustrated by V.H. Drummond

Carbonel the King of the Cats by Barbara Sleigh (Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1957). Illustrated by V.H. Drummond

Over the past few years, I’ve started tracking down books I read as a child and still remember, to see what I think of them now. Some of them I’ve had to buy; but I live close to a university library, which still has others on its shelves. I just reread Barbara Sleigh’s Carbonel, the King of the Cats (illustrated by V.H. Drummond), originally published 1955, and enjoyed it enough to think it deserves a review.

Sleigh was clearly an aelurophile; this book is dedicated to one cat and to the shades of four others. I’m pleased that its feline hero, Carbonel, is a black cat (as his name suggests!) — a breed that doesn’t get as much love as it deserves. He has very convincing catlike manners, mixing condescension, sarcasm, and occasional affection. At the same time, he fits one of the classic story formulas, being a lost heir of royal birth, with a title that he hopes to reclaim.

Carbonel the King of the Cats paperback edition (New York Review of Books, August 7, 2018)

Carbonel the King of the Cats paperback edition (New York Review of Books, August 7, 2018)

But the novel’s other hero is human: Rosemary Brown, a girl of ten, the daughter of a widow who supplements her pension by working as a seamstress. (Given the novel’s publication date, Rosemary’s father may well have died in the Second World War.) This is another classic formula, the child growing up under straitened circumstances — one that was still with us in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (a much better title than the American Sorcerer’s Stone).

I have to say that Rosemary is more enterprising than Harry: When her vacation from school begins, she comes up with the idea of finding some sort of work to earn money at, in order to help her mother. (Though to be fair, there might have been far fewer obstacles to such a project in 1955 than in 1997.)

Carbonel and its sequel The Kingdom of Carbonel (Puffin paperback editions, June 1961)

Carbonel and its sequel The Kingdom of Carbonel (Puffin paperback editions, June 1961)

In any case, that’s where the adventure begins: Rosemary decides that she could earn something by cleaning and sets out to buy a broom with the contents of her money box. As it turns out, what she gets is a witch’s broom, and one that’s crudely made, with a bundle of twigs at the sweeping end, and on the verge of falling apart.

But she also gets the witch’s cat, with her last three farthing, and learns that the broom not only flies, but grants her the power to understand what the cat says to her. Unfortunately, it’s not suited for the kind of indoor cleaning Rosemary has in mind: It looks more like a gardener’s broom.

Illustration by V.H. Drummond

Illustration by V.H. Drummond

But Carbonel, the cat, brings his own complications: He’s still bound by a spell the witch cast on him, and can’t reclaim his heritage and give the feline kingdom a proper ruler until he’s set free. And the conditions for doing so entangle Rosemary and her newly made friend John (the nephew of one of her mother’s customers) in a long series of complications.

I thought they were ingeniously worked out and had just the kind of odd magical prohibitions that are proper to a fairy story; and the resolution of Sleigh’s plot also resolves several other issues that came up earlier, from a small theatrical troupe’s troubles to the career of a retired witch. I really thought this book showed a lot of ingenuity in tying everything together.

Carbonel the King of Cats

Carbonel the King of Cats

I was also struck by a point I missed when I read this as a child, because of the other things I hadn’t read: In one chapter John figures out something significant and cites a maxim of Sherlock Holmes’s to explain how he did it — one from “A Scandal in Bohemia,” the story that gave us Irene Adler. I don’t know if I would have understood a story about royal love affairs and potential blackmail when I was 10, and perhaps John doesn’t, either. But clearly at least part of the story stayed with him.