Authors

New Covers

Sitrep: So, Goodlifeguide is a bit saturated at the moment so no garuntees that we'll see the manuscript back before the upcoming holiday.

In other news, I noticed some blog posts complaining about my covers. So, I spent the week poking around at 8 of them. I tried a few before with mixed results. This time I took a piecemeal approach with many. Some are enhanced with AI some like Regeneration have no AI enhancements, I just shifted the point of view.

To be clear: Same book, just new cover.

I will be replacing the old covers with these in the coming days.

I will be replacing the old covers with these in the coming days.Free Fiction Monday: Patriotic Gestures

Crime scene investigator Pamela Kinney hears the bad guys outside her house and smells smoke, but only realizes the next morning the crime they committed—burning the flag that had covered her daughter’s casket.

Her police colleagues call it a small crime, but she disagrees. She must solve it, and she must solve it now.

Chosen as one of the best mystery stories of the year, “Patriotic Gestures” explores the fine lines that run through American culture, and sometimes through Americans themselves.

“Patriotic Gestures“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Patriotic Gestures By Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Pamela Kinney heard the noise in her sleep—giggles, followed by the crunching of leaves. Later, she smelled smoke, faint and acrid, and realized that her neighbors were burning garbage in their fireplace again. She got up long enough to close the window and silently curse them; she hated it when they did illegal burning.

She forgot about it until the next morning. She stepped out her back door into the crisp fall morning, and found charred remains of her flag in the middle of her driveway. There’d been no wind during the night, fortunately, or all the evidence would have been gone.

Instead, there was a pile of burned fabric and a burn stain on the pavement. There were even footprints outlined in leaves.

She noted all of that with a professional’s detachment—she’d eyeballed more than a thousand crime scenes—before the fabric itself caught her attention. Then the pain was sudden and swift, right above her heart, echoing through the breastbone and down her back.

Anyone else would have thought she was having a heart attack. But she wasn’t, and she knew it. She’d had this feeling twice before, first when the officers came to her house and then when the chaplain handed her the folded flag which just a moment before had draped over her daughter’s coffin.

Pamela had clung to that flag like she’d seen so many other military mothers do, and she suspected she had looked as lost as they had. Then, when she stood, that pain ran through her, dropping her back to the chair.

Her sons took her arms, and when she mentioned the pain, they dragged her to the emergency room. She had been late for her own daughter’s wake, her chest sticky with adhesive from the cardiac machines and her hair smelling faintly of disinfectant.

And the feeling came back now, as she stared at the massacre before her. The flag, Jenny’s flag, had been ripped from the front door and burned in her driveway.

Pamela made herself breathe. Then she rubbed that spot above her left breast, felt the pain spread throughout her body, burning her eyes and forming a lump in the back of her throat. But she held the tears back. She wouldn’t give whoever had done this awful thing the satisfaction.

Finally she reached inside her purse for her cell, called Neil—she had trouble thinking of him as the sheriff after all the years she’d known him— and then she protected the scene until he arrived.

***

It only took him five minutes. Halleysburg was still a small town, no matter how many Portlanders sprawled into the community, willing to make the one and a half hour one-way daily commute to the city’s edge. Pamela had told the dispatch to make sure that Neil parked across the street so that any wind from his vehicle wouldn’t move the leaves.

And she had asked for a second scene-of-the-crime kit because she didn’t want to go inside and get hers. She didn’t want to risk losing the crime scene with a moment of inattention.

Neil pulled onto the street. His car was an unwieldy Olds with a souped up engine and a reinforced frame. It could take a lot of punishment, and often did.

As a result, the paint covering the car’s sides was fresh and clean, while the hood, roof and trunk looked like they were covered in dirt.

The sheriff was the same. Neil Karlyn was in his late fifties, balding, with a face that had seen too much sun. But his uniform was always new, always pristine, and never wrinkled. He’d been that way since college, a precise man with precise opinions about a difficult world.

He got out of the Olds and did not reach around back for a scene-of-the-crime kit. Annoyance threaded through her.

“Where’s my kit?” she asked.

“Pam,” he said gently, “it’s a low-level property crime. It’ll never go to trial and you know it.”

“It’s arson with malicious intent,” she snapped. “That’s a felony.”

He sighed and studied her for a moment. He clearly recognized her tone. She’d used it often enough on him when they were students at the University of Oregon. When they were lovers on different sides of the political fence, and constantly on the verge of splitting up.

When they finally did, it had taken years for them to settle into a friendship. But settle they did. They hardly even fought any more.

He went back to the car, opened the back seat and removed the kit she’d requested. She crossed her arms, waiting as he walked toward her. He stopped at the edge of the curb, holding the kit tight against his leg.

“Even if you somehow get the D.A. to agree that this is a cockamamie felony, you know that processing the scene yourself taints the evidence.”

“Why do you care so much?” she asked, hearing an edge in her voice that usually wasn’t there. The challenge, unspoken: It’s my daughter’s flag. It’s like murdering her all over again.

To his credit, Neil didn’t try to soothe her with a platitude.

“It’s the eighth flag this morning,” he said. “It’s not personal, Pam.”

Her chin jutted out. “It is to me.”

Neil looked down, his cheek moving. He was clenching his jaw, trying not to speak.

He didn’t have to.

She understood the irony of the statement. Somewhere in her pile of college paraphernalia was a badly framed newspaper clipping that had once been the front page of the Portland Oregonian. She’d framed the clipping so that a photo dominated, a photo of a much-younger Pamela with long hair and a tie-dye t-shirt, front and center in a group of students, holding an American flag by a stick, watching as it burned.

God, she could still remember how that felt, to hold a flag up so that the wind caught it. How fabric had its own acrid odor, and how frightened she’d been at the desecration, even though she’d been the one to light the flag on fire.

She had been protesting the Vietnam War. It was that photo and the resulting brouhaha it caused, both on campus and in the State of Oregon itself, that had led to the final break-up with Neil.

He couldn’t believe what she had done. Sometimes she couldn’t either. But she felt her country was worth fighting for. So had he. He joined up not two months later.

To his credit, Neil didn’t say anything about her own flag-burning as he handed her the kit. Instead he watched as she took photographs of the scene, scooped up the charred bits of fabric, and made a sketch of the footprint she found in the leaves.

She found another print in the yard, and that one she made a cast of. Then she dusted her front door for prints, trying not to cry as she did so.

“A flag is a flag is a flag,” she used to say.

Until it draped over her daughter’s coffin.

Until it became all she had left.

***

“I called the local VFW, Mom,” her son Stephen said over dinner that night. Stephen was her oldest and had been her support for thirty years, since the day his father walked out, never to return. “They’re bringing another flag.”

She stirred the mashed potatoes into the creamed corn on her plate. The meal had come from KFC: her sons had brought a bucket with her favorite sides, and told her not to argue with them about the fast food meal.

She wasn’t arguing, but she didn’t have much of an appetite.

They sat in the dining room, at the table that had once held four of them. Pamela had slid the fake rose centerpiece in front of Jenny’s place, so she wouldn’t have to think about her daughter.

It wasn’t working.

“Another flag isn’t the same, dumbass,” Travis said. At thirty, he was the youngest, unmarried, still finding himself, a phrase she had come to hate.

The hell of it was, Travis was right. It wasn’t the same. That flag these people had burned, that flag had comforted her. She had clung to it on the worst afternoon of her life, her fingers holding it tight, even at the emergency room, when the doctors wanted to pry it from her hands.

It had taken almost a week for her to let it go. Stephen had come over, Stephen and his pretty wife Elaine and their teenage daughters, Mandy and Liv. They’d brought KFC then, too, and talked about everything but the war.

Until it came time to take the flag away from Pamela.

Stephen had talked to her like she was a five-year-old who wanted to take her blankie to kindergarten. In the end, she’d handed the flag over. He’d been the one to find the old flagpole, the one she’d taken down when she bought the house, and he’d been the one to place the pole in the hanger outside the front door.

“The VFW says they replace flags all the time,” Stephen said to his brother.

“Because some idiot burned one?” Travis asked.

Pamela’s cheeks flushed.

“Because people lose them. Or moths eat them. Or sometimes, they get stolen,” Stephen said.

“But not burned,” Travis persisted.

Pamela swallowed. Travis didn’t remember the newspaper photo, but Stephen probably did. It had hung over the console stereo she had gotten when her mother died, and it had been a teacher—Neil’s first grade teacher? Pamela couldn’t remember—who had seen it at a party and asked if she really wanted her children to see that before they could understand what it meant.

“I don’t want another one,” Pamela said.

“Mom….” Stephen started in his most reasonable voice.

She shook her head. “It’s been a year. I need to move on.”

“You don’t move on from that kind of loss,” Travis said, and she wondered how he knew. He didn’t have children.

Then she looked at him, a large broad-shouldered man with tears in his eyes, and remembered that Jenny had been the one who walked him to school, who bathed him at night, who usually tucked him in. Jenny had done all that because Stephen at thirteen was already working to help his mom make ends meet, and Pamela was working two jobs herself, as well as attending community college to get her degree in forensic science and criminology. A pseudoscience degree, one of her almost-boyfriends had said. But it wasn’t. She used science every day. She needed science like she needed air.

Like she needed to find out who had destroyed her daughter’s flag.

“You don’t move on,” Pamela said.

Her boys watched her. Sometimes she could see the babies they had been in the lines of their mouths and the shape of their eyes. She still marveled at the way they had grown into men, large men who could carry her the way she used to carry them.

“But,” she added, “you don’t have to dwell on it, every moment of every day.”

And yet she was dwelling. She couldn’t stop. She never told her sons or anyone else, not even Neil who had become a closer friend in the year since Jenny had died. Neil, a widower now, a man who understood death the way that Pamela did. Neil, whose grandson had enlisted after 9/11 and had somehow made it back.

She was dwelling and there was only one way to stop. She had to use science to solve this. She couldn’t think about it emotionally. She had to think about it clinically.

She had her evidence and she needed even more.

The next morning, the local paper ran an article on the burnings, and listed the addresses in the police log section. So Pamela visited the other crime scenes with her kit and her camera, identifying herself as an employee of the State Crime Lab.

Since CSI debuted on television, that identification opened doors for her. She didn’t have to tell the other victims that she had been a victim too.

She took pictures of scorch marks on pavement and flag holders wrenched loose of their sockets. She removed flag bits from garbage cans, and studied footprints in the leaf-covered grass to see if they looked similar to the ones on her lawn.

And late that afternoon, as she stepped back to photograph yet another twisted flag holder beside a front door, she saw the glint of a camera hiding in a cobwebby corner of the door frame. The house was a starter, maybe 1200 square feet total. She wouldn’t have expected a camera here.

“Do you have a security system?” she asked the homeowner, a woman Travis’s age who looked like she hadn’t slept in weeks. Her name was Becky something. Pamela hadn’t really heard her last name in the introduction.

“My husband put it up,” Becky said, her voice shaking a little. “I have no idea how it works.”

“When will he be back?” Pamela asked.

Becky shrugged. “When they cancel stop-loss, I guess.”

Pamela felt her breath slide out of her body. “He’s in Iraq?”

Becky nodded. “I put the flag up for him, you know? And I haven’t told him what happened to it. I’ve gotta find someone to fix the holder, and I have to get another flag.”

Pamela looked at the house more closely. It needed paint. The bushes in front were overgrown. There were cobwebs all over the windows, and dry rot on the sills. Obviously the couple had purchased it expecting someone to work on it.

Either the money wasn’t there, or the husband had planned to do the work himself.

“I can fix the holder,” Pamela said. “If you have a few tools.”

“My husband does,” Becky said. “I can show them to you.”

“I have a few things to finish, and then you can show me,” Pamela said.

She dusted for prints, and then, for comparison, took Becky’s and some off the husband’s comb, which hadn’t been touched since he left. Then Pamela went into his workroom, which also hadn’t been touched, and took a hammer, some screws, and a screwdriver.

It took only ten minutes to repair the flag holder. But in that time, she’d made a friend.

“How’d you learn how to do that?” Becky asked.

“Raised three kids alone,” Pamela said. “You realize there’s not much you can’t do, if you just try.”

Becky nodded.

Pamela glanced at the camera. Untended since the husband left. It was probably in the same state of disrepair as the rest of the house.

“Can I see the security system?” she asked.

“It’s not really a system,” Becky said. “Just the cameras, and some motion sensors that’re supposed to alert us when someone’s on the property. But they clearly don’t work any more.”

“Let me see anyway,” Pamela said.

Becky took her past the workroom, into a small closet filled with electronics. The closet was warm from the heat the panels gave off. Lights still blinked.

Pamela stared at it all, then touched the rewind button on the digital recorder. On the television monitor, she watched an image of herself fixing the flag holder.

“It looks like the camera’s still working,” she said. “Mind if I rewind farther?”

“Go ahead.”

Backwards, she watched darkness turn to day. Saw Neil inspect the hanger. Saw Becky crying, then the tears evaporate into a stare of disbelief before she backed off the porch and away from the scene.

Back to the previous night. No porch light. Just images blurred in the darkness. Faces, not quite real, mostly turned away from the camera.

“Got a recordable DVD?” Pamela asked.

“Somewhere.” Becky vanished into the house. Pamela studied the system, hoping that she wouldn’t erase the information as she tried to record it.

She rewound again. Studied the faces, the half turned heads. She saw crew cuts and piercings and hoodies. Slouchy clothes worn by half the young people in Halleysburg.

Nothing to identify them. Nothing to separate them from everyone else in their age group.

Like her, her hair long, her jeans torn, as she stood front and center at the U of O, a burning flag before her.

She made herself study the machine, and figured out how to save the images to the disk’s hard drive so that they wouldn’t be erased. Then she inspected the buttons near the machine’s DVD slot.

“Here,” Becky said, thrusting a packet at her.

DVD-Rs, unopened, dust-covered. Pamela used a fingernail to break the seal, then pulled one out, and inserted it in the slot. She managed to record, but had no way to test. So she made a few more copies, feeling somewhat reassured that she could come back and try to download the images from the hard drive again.

“Will this catch them?” Becky asked while she watched the process.

“I don’t know,” Pamela said. “I hope so.”

“It’s just, they got so close, you know.” Becky’s voice shook. “I didn’t know anyone could get that close.”

It took Pamela a moment to understand what she meant. Becky meant that they had gotten close to the house. Close to her. The burning hadn’t just upset her, it had frightened her, and made her feel vulnerable.

Odd. All it had done to Pamela was make her angry.

“Just lock up at night,” Pamela said after a minute. “Locks deter ninety-percent of all thieves.”

“And the remaining ten percent?”

They get in, Pamela almost said, but thought the better of it.

“They don’t usually come to places like Halleysburg,” she said. “Why would they? We all know each other here.”

Becky nodded, seemingly reassured. Or maybe she just wanted to abandon an uncomfortable topic.

Pamela certainly did. She wanted to play with the images, see what she could find.

She wanted a solid image of the culprits, one that she could bring to Neil.

Maybe then, he would stop complaining that this was a petty property crime. Maybe then he might understand how important this really was.

***

But it was her own words that replayed in her head later that night as she sat in front of her computer.

They don’t usually come to places like Halleysburg…. We all know each other here.

She had lied to make Becky feel better, but the words hadn’t felt like a lie. Thieves really didn’t come here. There was no need. There was richer pickings in Portland or Salem or the nearby bedroom communities.

Besides, it was hard to commit a crime here without someone seeing you.

Except under cover of darkness.

Her home office was quiet. It overlooked the back yard, and she had never installed curtains on the window, preferring the view of the year-round flower garden she had planted. At the moment, her garden was full of browns and oranges, fall plants blooming despite the winter ahead. She had little lights beneath the plants, lights she usually kept off because they spiked her energy bill.

But she had them on now. She would probably have them on for some time to come.

Maybe Becky wasn’t the only one who felt vulnerable.

Pamela put one of the DVDs in her computer, and opened the images. They played, much to her relief, so she copied the images to her hard drive and removed the DVD.

Her computer at home wasn’t as good as her computer at work. But it would have to do.

She didn’t want to do any work on this case at the State Crime Lab if she could help it. The lab was so understaffed and so overworked that it usually took four months to get something tested. When she last checked, more than 600 cases were backlogged, some of them dating back more than nine months.

Those cases were bigger than hers. The backlogs were semen samples from possible rapists and blood droplets from the scene of a multiple murder case.

She couldn’t, in good conscience, bring something personal and private to the lab. She would work here as long as she could. Then if she couldn’t finish here, she might be able to convince herself that the time she took at the lab would go toward an arson case—a serious one, not a petty property crime, as Neil had called it.

Petty property crime.

Funny that they would be on opposite sides of this issue too.

Pamela went through the images frame by frame, looking for clear faces. Her computer didn’t have the face recognition software that one of the computers at the lab had, but she had installed a home version of image sharpening software. She used it to clean out the fuzz and to lighten the darkness, trying to find more than a chin or the corner of an ear.

Finally she got a small face just behind the flag, a serious white face with a frown—of disapproval? She couldn’t tell—and a bit of an elongated chin. Enough to see the wisp of a beard—a boy’s beard, more a wish of a beard than the real thing—and a tattooed hand coming up to catch the flag as the person almost blocking the camera yanked the pole out of the holder.

She blew up the image, softened it, fixed it, and then felt tears prick her eyes.

They don’t usually come to places like Halleysburg.

No. They grew up here. And worked at the grocery store down the street to pay for their football uniforms at the underfunded high school. They collected coins in a can on Sunday afternoons for Boosters, and they smiled when they saw her and respectfully called her Mrs. Kinney and asked, with a little too much interest, how her granddaughters were doing.

“Jeremy Stallings,” she whispered. “What the hell were you thinking?”

And she hoped she knew.

***

Neil wouldn’t let her sit in while he questioned Jeremy Stallings. He was appalled she’d even asked.

“That sort of thing belongs on TV and you know it,” he’d said.

But she also knew he probably wouldn’t do much more than slap the boy on the wrist, so what would be the harm? She hadn’t made that argument, though.

Instead, she waited on the bench chair outside the sheriff’s office conference room, which doubled as an interview room on days like this, and watched the parade of parents and lawyers as they trooped past.

No one acknowledged her. No one so much as looked at her. Not Reg Stallings, whose brother had sold her the house, or his wife June, who had taken over the PTA just before Travis got out of high school. No one mentioned the friendly exchanges at the high school football games or the hellos at the diner behind the movie theater. It was easier to forget all that and pretend they weren’t neighbors than it was to acknowledge what was going on inside that room.

Then, finally, Jeremy came out. He was wearing his baggy pants with a Halo t-shirt hanging nearly to his knees. He wore that same frown he’d had as he took the flag off from Becky’s front door.

He glanced at Pamela, then looked away, a blush working its way up the spider tattoo on his neck into his crew cut.

His parents and the lawyers led him away, as Neil reminded all of them to be in court the following morning.

Neil waited until they went through the front doors before coming over to Pamela.

She stood, her knees creaky from sitting so long. “He confess?”

Neil nodded. “And gave me the names of his buddies.”

Pamela bit her lower lip. “Funny,” she said, “he didn’t strike me as the type to be a war protestor.”

Neil rubbed his hands on his pristine shirt. “Is that what you thought?”

“Of course,” Pamela said. “Every house he hit, we’re all military families.”

“Who happened to be flying flags, even at night.” There was a bit of judgment in Neil’s voice.

She knew what he was thinking. People who knew how to handle flags took them down at dusk. But she couldn’t bear to touch hers. She hadn’t asked Becky why hers remained up, but she would wager the reason was similar.

And it probably was for every other family Jeremy and his friends had targeted.

“That’s the important factor?” she asked. “Night?”

“And beer,” Neil said. “They lost a football game, went out and drank, and that fueled their anger. So they decided to act out.”

“By burning flags?” Her voice rose.

“A few weeks before, they knocked down mailboxes. I’m going to hate to charge them. There won’t be much left of the football team.”

“That’s all right,” Pamela said bitterly. “Petty property crimes shouldn’t take them off the roster long.”

“It’s going to be more than that,” Neil said. “They’re showing a destructive pattern. This one isn’t going to be fun.”

“For any of us,” Pamela said.

***

Her hands were shaking as she left. She had wanted the crime to mean something. The flag had meant something to her. It should have meant something to them too.

God, Mom, for an old hippie, you’re such a prude. Jenny’s voice, so close that Pamela actually looked around, expecting to see her daughter’s face.

“I’m not a prude,” she whispered, and then realized she was reliving an old argument between them.

Sure you are. Judgmental and dried up. I thought you protested so that people could do what they wanted.

Pamela sat in the car, her creaky knees no longer holding her.

No, I protested so that people wouldn’t have to die in another senseless war, she had said to her daughter on that May afternoon.

What year was that?

It had to be 1990, just before Jenny graduated from high school.

I’m not going to die in a stupid war, Jenny had said with such conviction that Pamela almost believed her. We don’t do wars any more. I’m going to get an education. That way, you don’t have to struggle to pay for Travis. I know how hard it’s been with Steve.

Jenny, taking care of things. Jenny, who wasn’t going to let her cash-strapped mother pay for her education. Jenny, being so sure of herself, so sure that the peace she’d known most of her life would continue.

To Jenny, going into the military to get a free education hadn’t been a gamble at all.

Things’ll change, honey, Pamela had said. They always do.

And by then I’ll be out. I’ll be educated, and moving on with my life.

Only Jenny hadn’t moved on. She’d liked the military. After the First Gulf War, she’d gone to officer training, one of the first women to do it.

I’m a feminist, Mom, just like you, she’d said when she told Pamela.

Pamela had smiled, keeping her response to herself. She hadn’t been that kind of feminist. She wouldn’t have stayed in the military. She wasn’t sure she believed in the military—not then.

And now? She wasn’t sure what she believed. All she knew was that she had become a military mother, one who cried when a flag was burned.

Not just a flag.

Jenny’s flag.

And that’s when Pamela knew.

She wanted the crime to mean something, so she would make sure that it did.

***

She brought her memories to court. Not just the scrapbooks she’d kept for Jenny, like she had for all three kids, but the pictures from her own past, including the badly framed front page of the Oregonian.

Five burly boys had destroyed Jenny’s flag. They stood in a row, their lawyers beside them, and pled to misdemeanors. Their parents sat on the blond bench seats in the 1970s courtroom. A reporter from the local paper took notes in the back. The judge listened to the pleadings.

Otherwise, the room was empty. No one cheered when the judge gave the boys six months of counseling. No one complained at the nine months of community service and even though a few of them winced when the judge announced the huge fines that they (and not their parents) had to pay, no one said a word.

Until Pamela asked if she could speak.

The judge—primed by Neil—let her.

Only she really didn’t speak. She showed them Jenny. From the baby pictures to the dress uniform. From the brave eleven-year-old walking her brother to school to the dust-covered woman who had smiled with some Iraqi children in Baghdad.

Then Pamela showed them her Oregonian cover.

“I thought you were protesting,” she said to the boys. “I thought you trying to let someone know that you don’t approve of what your country is doing.”

Her voice was shaking.

“I thought you were being patriotic.” She shook her head. “And instead you were just being stupid.”

To their credit, they watched her. They listened. She couldn’t tell if they understood. If they knew how her heart ached—not that sharp pain she’d felt when she found the flag, but just an ache for everything she’d lost.

Including the idealism of the girl in the picture. And the idealism of the girl she’d raised.

When she finished, she sat down. And she didn’t move as the judge gaveled the session closed. She didn’t look up as some of the boys tried to apologize. And she didn’t watch as their parents hustled them out of court.

Finally, Neil sat beside her. He picked up the framed Oregonian photograph in his big, scarred hands.

“Do you regret it?” he asked.

She touched the edge of the frame.

“No,” she said.

“Because it was a protest?”

She shook her head. She couldn’t articulate it. The anger, the rage, the fear she had felt then. Which had been nothing like the fear she had felt every day her daughter had been overseas.

The fear she felt now when she looked at Stephen’s daughters and wondered what they’d chose in this never-ending war.

“If I hadn’t burned that flag,” she said, “I wouldn’t have had Jenny.”

Because she might have married Neil. And even if they had made babies, none of those babies would have been Jenny or Stephen or Travis. There would have been other babies who would have grown into other people.

Neil wasn’t insulted. They had known each other too long for insults. Instead, he put his hand over hers. It felt warm and good and familiar. She put her head on his shoulder.

And they sat like that, until the court reconvened an hour later, for another crime, another upset family, and another broken heart.

___________________________________________

“Patriotic Gestures“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Patriotic Gestures

Copyright © 2016 by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

First published published in Scene of The Crime, edited by Dana Stabenow, Running Press, 2008

Published by WMG Publishing

Cover and Layout copyright © 2016 by WMG Publishing

Cover design by WMG Publishing

Cover art copyright © Americanspirit/Dreamstime

This book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. All rights reserved. This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

The Inheritance: Chapter 6 Part 1

Bonus points for correctly identifying the popular culture reference.

Drishya Chandran blinked her big brown eyes. On paper, she was twenty-one. To Elias, she looked about fifteen at most.

It’s not that the kids are getting younger; it’s that I’m getting older.

“I’m sorry,” Drishya said. “I honestly didn’t see anything.”

They had commandeered the Elmwood Public Library and through the glass window of the conference room Elias could see the gate looming like a dark hungry mouth, bathed in the glow of the floodlights. No matter how many lives they threw into it, it would never be enough. It was past one in the morning, and he was out of coffee.

“Walk me through it one more time,” he said.

“The drill head jammed,” Drishya said. “I showed it to Melissa. She said to go get the new one from the cart in the tunnel. I went to get it. The next thing I know Wagner is running out of the tunnel, and Melissa is behind him, and her face doesn’t look right. I’m like okay, I guess we are doing that now, so I turned around and ran to the gate. I heard an explosion behind us, so I didn’t look back. I didn’t even know London made it until I was out.”

“Why was the cart in the tunnel and not at the site?” Elias asked.

“It didn’t fit. The site slopes to the stream and there wasn’t a lot of flat ground, so we could only get three of the four carts in.” Drishya counted off on her fingers. “Cart One had the generator, lights, and first aid, so it had to come in. Carts Two and Three were for the ore. Adamantite is heavy, so we didn’t want to carry it too far. Cart Four with the spare parts had to live outside.”

“So there was adamantite at the site?” He’d read Leo’s notes of Melissa’s interview, but it seemed almost unbelievable that so much adamantite could exist in one place.

“Oh yes. That’s how my drill broke. Chipped off a chunk this big.” Drishya held her hands out as if lifting an invisible basketball.

“Was the adamantite in plain view?”

The miner shook her head. “No. Buried, and half of it underwater. It took the DeBRA about 10 minutes to find it. She had to mark it with paint for us.”

Was this why they were attacked? Was something protecting the ore?

Drishya sighed. “It’s awful, isn’t it? Everyone is dead.”

“It is, and they are,” Elias confirmed.

“I knew we would get a big bonus when we found the gold, and then the DeBRA came up with adamantite. I was so excited. I thought I could finally put a deposit on the house. My mom isn’t doing so well. I’ve got to get us out of the apartment, and I’m the only one working.”

Gold? What gold? “I’m sorry your mother is in bad health, and that you had to go through this trauma. You may want to see Dr. Park. He has a room set up downstairs.”

“I’m okay. I didn’t see any of it,” Drishya said. “I’ve only been working for 6 months. I didn’t even know people that well…”

He’d seen this before. Some people grieved when faced with death, others got angry, and some tried to disconnect themselves from what happened.

“I understand,” he said. “Still, it might be a good idea. You’ve lost colleagues in a sudden traumatic way. Things like that can fester.”

“I’ll think about it,” she said.

“So how much gold was there?”

“A lot. It was everywhere in the water, like rocks. We weren’t even drilling; we were pulling it out by hand. Nuggets the size of an apple. We ended up dumping like fifty pounds of it to make room for the adamantite, and we’d been only gathering it for about five minutes.”

“I see. I appreciate your help, Ms. Chandran. The guild is grateful for your assistance. Please get some rest.”

She got up and paused. “You are a lot less scary than I thought you would be.”

“That’s good to hear.”

“Just so you know, Wagner told me not to talk to you.”

Elias raised his eyebrows. “Oh?”

“He said that miners don’t go into the breaches with guildmasters. They go with escort captains. He said it was something to keep in mind.”

“Thank you for your honesty.”

She nodded and walked out.

Elias pulled up the interview notes on his tablet. Neither Melissa nor London said anything about the gold. Malcolm wouldn’t have seen the adamantite, but gold was an entirely different beast.

Was it just gold? Was that it? He’d been wracking his brain, trying to find the reason for the lapse in procedure, having this back and forth with Leo, wondering what he was missing, and all this time, the answer was depressingly simple. Well, no shit, Sherlock, here it is. Greed.

He had put so many regulations and checks in place, and somehow greed always won. He was so fucking tired. Things were much simpler in the breach. The enemy was in front, the support was behind, and he didn’t have to wade through the swamp of human failings. He couldn’t wait to get out of this conference room and into his armor. He had a powerful urge to slice something with his sword.

Leo appeared in the open doorway like a wraith manifesting, met his gaze, and stepped back.

“Come inside and shut the door,” Elias growled.

Leo came in and closed the door behind him.

“Sit.”

Leo sat.

“Why do baby miners think I’m scary?”

“Because you are, sir. Most people find a man who can cut a car in a half with a single strike and then throw the pieces at you frightening.”

“Hmm.”

“Also we offer the highest pay and the best benefits among the top tier guilds, and you are their boss who holds their livelihood in his gauntleted fingers…”

Elias raised his hand. “Did you know there was gold at the mining site?”

Leo’s eyes flashed with white. “I did not.”

“Apparently it was in the water. Nuggets the size of apples. Finally, I know something before you do.”

“Congratulations, sir.”

Elias let that go, pulled up the map of the site on his tablet, and pointed at the three tunnels, each carrying a current of water that merged into a single stream. “Gold washes downstream.”

“Malcolm left the tunnels open because he wanted to maximize the profit from the site.” Leo’s face snapped into a hard flat mask. “He must’ve expected that once they cleared the site, they would gather more gold upstream.

“Remind me, how much did Malcolm make last year?”

“Seven million.”

“I want to know why gold got him so excited that he risked nineteen lives by leaving the tunnels unsecured.”

“Nineteen?” Leo frowned. “The mining crew, the escort, the DeBRA…”

“And the dog.”

“Oh.”

“Malcolm took a significant risk. That’s not just greed. That’s desperation. How are his finances?”

“Squeaky clean as of the last audit, which was two months ago. Credit score of 810, low debt to assets, less than 10K owed on credit cards. I’m following up on a couple of things. We should know more in a few hours. Do you want me to get Wagner in to talk to you?”

“He won’t tell me anything. Wagner is forty-nine years old. He was a coal miner before the gates appeared, and we are his third guild. He’s used to getting screwed over by his bosses.”

“So, he developed an adversarial relationship with us despite fair treatment,” Leo said. “Seems counterintuitive.”

“It doesn’t matter what kind of treatment he gets. He’s cooked. He doesn’t trust us, he will never trust us, and he will always resent us no matter how many benefits he gets.”

“That’s not even logical.”

“It isn’t. It’s an ingrained emotional response. Trust me, we won’t get anything out of him. I’d like you to reinterview Melissa instead. As you said, I’m scary, so she may do better with you. Don’t be confrontational. Be sympathetic and understanding. Make it us against the government: we need to tell the DDC something and we need her help to make them go away. Imply that her cooperation will be remembered and appreciated.”

Leo nodded. “Should I bring up the families?”

Elias shook his head. “Normally the foreman would be the last to get out, just before the escorts. She was at the head of the pack. Either she was incredibly lucky, or she abandoned her crew and ran for her life. Either way, there is guilt there. If you lean too hard on it, she might shut down. Go with ‘you were just doing your job, and we don’t blame you for surviving’ instead. Get her a coffee, get some cookies, interview her in a comfortable setting, and see if she thaws and starts talking. If she goes off on a tangent, let her. Don’t rush. You are her friend; you are there to listen.”

Leo nodded. “Will do.”

“Did Haze get the children?”

“Yes. They’ve just arrived at HQ. I still don’t think this is wise.”

Twenty-eight people died in the breach. Fourteen members of the assault crew, nine miners, four escorts, and Adaline Moore. Twelve of the deceased left behind minor children. Of all of them, only Adaline Moore’s kids had no immediate family to take care of them.

The media devoured any news related to the guilds and gates, and the death of a prominent DeBRA would set off fireworks. Once the news broke, Adaline’s children would become the center of a news cycle. They would be overwhelmed, used, wrung dry for the sake of the cheap emotional punch, and then abandoned to their grief. If they were lucky, the country would forget they existed. If they were unlucky, someone would take note of two vulnerable orphans with a million-dollar life insurance payout.

“I will not allow Adaline’s children to be fed to the media circus,” Elias said. “They are safer at the Guild HQ. DDC hasn’t made any notifications yet, but we both know it will get out. I don’t need some asshole showing up at their door, sticking a microphone into their faces, and asking how they feel about their mother dying. All Haze told them was that Adaline is missing in the breach. They will find out what happened from me, personally.”

He would take care of that in the morning.

“Adaline Moore would have made provisions,” Leo said.

“I’m sure she did. Until we know what they are, we will take care of it.”

“This will be seen as Cold Chaos controlling access to the children because we have something to hide. We are trying to minimize the media’s attention, but they love conspiracies. In an effort to keep the story small, we may end up making it bigger.”

“That’s fine. If they want to paint us as the villain of that story, let them. We will survive. We are the third largest guild in the country.”

Leo sighed quietly.

“I called Felicia,” Elias told him.

Felicia Terrell was a powerhouse attorney, and she specialized in guild-related litigation. He spoke to her two hours ago. She called him a marshmallow and promised to show up first thing in the morning. The children would be well protected from everyone, including Cold Chaos.

Elias leaned back. He was so over it. As soon as he hammered the assault team together, he would enter the gate. He couldn’t wait to get out of this conference room. There was no politics in the breach.

Leo was still sitting in the chair. Some other problem must’ve reared its ugly head.

“Lay it on me,” Elias said.

“We can’t find Jackson.”

“What do you mean, you can’t find him?”

“He was supposed to fly out of Tokyo twenty minutes ago. He didn’t make it to the plane, and he isn’t answering his phone. I’m on it.”

Jackson was arguably the best healer in the US. He didn’t drink, he didn’t do drugs, and his biggest vice was collecting expensive bonsai. The man did not go AWOL. Jackson was always where he was supposed to be. He was calm, competent, powerful, and respected wherever he went, because he did things like walk into other guilds’ gates and rescue their assault teams from disaster when asked. Nothing could happen to Jackson.

“Do whatever you have to do, but find him, Leo.”

The XO nodded. “I will.”

The post The Inheritance: Chapter 6 Part 1 first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

The Wild Road — cover

Monday Meows

One of these things is not like the others

One of these things just isn’t the same

One of these things is not like the others

One of these things just doesn’t belong

Can you guess which one before we finish this song?

Multiverse 8 Snippet 1

Sitrep:

I sent MV8 off to Rea on Monday. She got it back to me yesterday, and I did the edits and then sent it off to Goodlifeguide for final formatting. There are... 5 stories? Two new original science fiction, 2 Federation stories, and 1 PRI story.

We'll see if I get it back before Memorial Day. Fingers crossed.

In other news, I've spent the past week running 8 of my old covers through SeaArt to enhance them. I am wrapping up the last one but I'm torn. I'm not sure if I should go with the enhanced original design or one of Bast.

I'll post the new covers in a later post.

Anyway, on to the snippet!

Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE MicrosoftInternetExplorer4 /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Table Normal"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0in; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman","serif";}

Invasion

Yep, another alien invasion story. But this one has been kicking around for a while. I think it came up after seeing some of the invasion stories where humanity looses initially? Like Falling Skies and such. Of course, I have to put my own twist on things. :)

Glen Aurellius was out hunting but aware it wasn’t a good time for it. Most of the animals were active at dawn and dusk. But he had to hunt; he only had so much food on him. His backpack was filled with odds and ends to help him survive but was light on fresh food.

He really needed to stop for a while and try to smoke whatever he caught so it would last longer. Either that or trade the excess again or give it up rather than have another survivor try to rob him of it. It wasn’t worth the fight.

He heard some motion in the ferns up ahead and paused. He knelt slowly, feeling the ache in his knees from the motion, but he ignored it as he pulled his bow up and notched an arrow.

The animal that came out of the bush was a feral pig, maybe six months to a year old. It wasn’t very bright; it went for the pile of nuts and berries he’d left out as bait.

He lined up his hunting arrow and made certain he had a solid shot before he let loose. The arrow swished and hit the pig in the shoulder. It squealed in surprise and tried to run but stumbled.

He snapped another arrow up and shot the beast before it got too far. He wasn’t in the mood to chase it. That arrow hit the head though and had a point not a broad head. It didn’t have the power to penetrate the skull. It stuck out like one of those spears used to torment fighting bulls.

He didn’t think of that much as he pulled a third arrow and shot it. That caught the pig in the ass. It stumbled and then fell as its movements and the broad head arrow tore something vital within it. It finally fell gasping into the ferns and dirt.

Glen went over and used his bowie knife to slit the throat as the pig twitched. He didn’t want it to come back to life. He knew he was being stupid; you were supposed to wait until the kill was dead but he didn’t feel safe.

He watched the blood flow as he pulled his arrows and examined them. He flicked a bit of gore off one and frowned at the tip of the second arrow. The metal was okay but the arrow wood behind it had a slight crack. That’s what he got for using a point and not using composite arrows.

He shook his head and cleaned the tip on the bristle hide of the fallen beast. He was going to eat well tonight even though he wasn’t too fond of pork. Oh, bacon was fine, but ham was a bit greasy.

Still, food was food.

He put the arrows in the quiver and set it on top of his pack and the bow and then got to work. He pulled a camping rope out and tossed one end over the tree limb above. He knotted the other around a rear leg and then yanked it up. Once the pig was jacked up, he tied off the rope and gutted it.

He was working fast and dirty, there was no telling what was in the area. A bear, wolverine, big cat, or anything else. The smell of blood would attract other predators soon enough. The flies would get fierce too in the early summer heat.

He flicked a fly away and then began to portion the pig up. It was only eighty pounds or so, sixty with the offal unloaded. He left the head and some of the bones behind. He wrapped the rest in a piece of plastic and then tested it as he got up.

At forty-two he thought he could handle the pack and meat but it was not going to be a pleasant haul. He was going to need to find shelter soon as well as some firewood. Once he was somewhere dependable, he could break the meat down further.

Scavengers were welcome to the leftovers or ex-wives, whichever came first he thought in amusement.

He had been married and divorced twice. He’d been something of a JOAT, bouncing around with careers. He’d never really found his calling. His dreams of being in the military had died when he’d been injured in a football game. From there he’d moved on to a few other career paths. He had loved science fiction though, which was why he’d ended up on the west coast.

Now he was trying to make it back to the east coast to the old family farm, if it even existed. Picking his way on foot was a bitch though. There were no vehicles running; anyone stupid enough to get one going usually ended up as target practice for the bastards in orbit.

Involuntarily, he glanced to the sky. It was not quite noon; he had plenty of time to find shelter.

He heard a commotion ahead of him and instinctively paused and then turned. He wasn’t certain what it was but he didn’t want to encounter it with so much weight and his primary weapons locked down behind him. At the moment, he had his machete and knife available.

He walked around a big tree but then paused and slowly put his hands up at the sight of an alien Centaur standing there holding a rifle. A human in camo was standing next to him.

“Well, what do we have here?” the guy said. “I didn’t know we ordered take out, but I think we’ll take it to go,” the guy said.

Glen had a sinking heart. The sounds of something moving in the brush intensified. He turned his head slightly and saw another Centaur charge up and then stop. It snorted at him. It was holding a rifle in its arms casually.

“Um, hi, guys?” Glen said.

The other human snorted. “I believe lunch is served,” he said as he indicated that Glen should unload.

Glen sighed and hoped it was just a robbery.

~~~*~~~

The Inheritance: Chapter 5 Part 3

The rollercoaster note is still in effect: this will be a scary ride, but it will arrive safely. Ada is not a pushover.

Something was wrong with Bear.

We had cut our way through the stalker tunnels. Our trail was littered with corpses, and we had just killed our fifteenth beast. It hadn’t gotten easier, not at all. I was so worn down, I could barely move. My body hurt, the ache spreading through the muscles like a disease, sapping my new strength and making me slow.

Bear stumbled again. I thought it was fatigue at first, but we had rested for a few minutes before this last fight, and it hadn’t helped at all. I had kept her from serious injury. She’d been clawed and bitten once, but the bite had been shallow, so it likely wasn’t the blood loss.

Bear whined and fell.

Oh god.

I dropped on my knees by her. “What is it?”

The shepherd looked up at me, her eyes puzzled and trusting.

I flexed, focusing on her body, concentrating all of my power on her. What was it? Blood loss, infection…

The faint outline of Bear’s body glowed with pale green, which told me nothing. I had to push deeper. I focused my power into a thin scalpel and used it to slice through the surface glow.

It resisted.

I sliced harder.

Harder!

It broke, splintering vertically into layers, and I punched through it. It was almost like falling through the floor to a lower level.

Bear’s body lit up with pale blue, the glow tracing her nerves, her blood vessels, and her organs. I had never before been able to do that, but that didn’t matter now.

Toxin. She was filled with it. I saw it, tiny flecks glowing brighter as they coursed through her like some deadly glitter. I had to find the origin of it. Was it from a stalker bite? No, the concentration of poison wasn’t dense there. Then what was it? Where was it the highest?

Her lungs. That fucking glitter saturated her lungs, slipping into her bloodstream with every breath. I had to go deeper. I pushed with my power. Before, it was like trying to slice through glass. Now it felt like punching through solid rock, and I hammered at it.

The top layer of the blue glow cracked, revealing a slightly different shade of blue underneath. I hit it again and again, locked onto the glitter with every drop of willpower I had.

The tiny specks expanded into spheres. What the hell was that?

I pounded on the glow, trying to enlarge it. The spheres came into greater focus. They weren’t uniformly round; they had four lobes clumped together and studded with spikes.

What are you? Where did you come from?

A flash of white cut my vision. I went blind. It lasted only a moment, but I knew I hit a wall. I wasn’t going any deeper. I would have to work at this level.

I blinked, trying to reacquire my vision.

My thighs were glowing with blue.

I jerked my hands up. Pale glitter swirling through my arms and fingers. This dust, this thing was inside me too, and I couldn’t identify it.

We were both infected, and it was killing us.

Panic drenched me in icy sweat. I wanted to rip a hole in my legs and just force the glitter out.

Bear whined softly like a puppy.

I was losing her. She trusted me, she followed me, and she fought with me, and now she was dying.

“You can’t die, Bear. Hold on. Please hold on for me.”

Bear licked my hand.

The urge to scream my head off gripped me. Wailing wouldn’t help. If only I could identify the poison.

Why couldn’t I identify it? Was it because it was inside us and it had become part of us? Or was I just not strong enough to differentiate it from our blood? It had started in the lungs, so we must have inhaled it.

I took a deep breath and exhaled on my hands.

There it was! A trace of the lethal glitter. I focused on it. The four-lobes spiked clumps, swirling, swirling… Something inside me connected, and I saw a faint image in my mind. The mauve flowers. We had been poisoned by their pollen.

I flexed harder, stabbing at the pollen with my talent. The tiny flecks opened up into a layered picture in my mind, and the top layer showed how toxic it was…

Oh god.

We were almost out of time. We needed an antidote. Now.

I strained, trying to access whatever power lay inside me, the same one that showed me the Grasping Hand and gave me the stalkers’ name. It didn’t answer.

Please. Please help me.

Nothing.

We would die right here, in this tunnel. I knew it, I could picture it, me wrapped around Bear, hugging her as we both grew cold…

No. There had to be an answer. We hadn’t come all this way to lay down and die. We did not kill and fight all these damn stalkers –

The stalkers. The stalkers went to the lake to drink. The flowers were all over the shore, but the stalkers had died because the lake dragon had torn them apart. The flowers didn’t poison them.

I jumped to my feet and ran to the nearest corpse. My talent reached out and grasped the body. There was pollen on the fur and on the muzzle and a faint smudge in the lungs, but none anywhere else. Not a trace in the blood. They were immune.

The poison had to be eliminated in the bloodstream. If it was purged in the liver or any other organ, there would’ve been traces of it in the blood vessels but there were none.

I flipped the stalker on its back, shaped my sword into a knife, and stabbed the corpse, slicing it from the neck to the groin. Bloody wet innards spilled out. I dug in the mush, pushing slippery tissue aside until I found the hard sack of the heart. I carved it out and pulled the bloody clump free.

Flex.

The heart glowed with blue. Toxic. It would poison us, too, but there was a slim chance we could make it. It was the difference of might-be-dead from the stalker heart or definitely-dead from the pollen. We didn’t have hours, we had minutes. The heart had to be the answer.

I put it on a flat rock and minced the tough muscle into near mush. I scooped a handful of the bloody mess and staggered over to Bear.

She was still breathing. There was still a chance.

I pried her jaws open and shoved a clump of the stalker mince into her throat. She gulped and gagged. I held her mouth closed.

“Swallow, please swallow…”

Bear gulped again. Yes. It went down.

“What a good girl. The best girl. One more time. Let’s get a little more in there.”

I forced two more handfuls into her and flexed. The concentration of pollen in her stomach dimmed. I had no idea if the immune agent in the stalker blood would spread or if it would be broken down by stomach acid. It didn’t matter. We were all out of choices.

Bear let out a soft, weak howl, almost a gasp. It must have hurt.

“I’m so sorry. I wouldn’t hurt you if there was any other way.”

If I ate the heart now, there was no telling what it would do to me. I could pass out right here, and we would both become stalker dinner.

About twenty minutes ago we had walked by a narrow stone bridge that spanned a deep cavern. There had been a depression at the other end, a little cave within the cave. I’d thought it would be a good place to rest, because the stalkers could only come at us one by one, but I had wanted to get out of the tunnels. At the time, it seemed better to just keep moving. It seemed like forever ago, but it had just happened. We had to find a place to hide, and that was the closest safe spot I could think.

I should be able to find the bridge again. I just had to follow the trail of bodies and make it there before the poison got me.

I picked Bear up. She felt so heavy, impossibly heavy.

I spun around and trudged back the way we came.

The post The Inheritance: Chapter 5 Part 3 first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Life and Other Dishes

I have a weird feeling this week. It’s like I overlooked something or forgot some bill, and I keep checking to see what I missed and can’t find it. And it’s Thursday already. How? How?

Gordon’s surgery is next week. They will clean the scar tissue from his shoulder, and he will have to immediately go into physical therapy. If we miss an Inheritance installment, that’s probably why. Hopefully we will stay on track. I am going to try to get the next three posts lined up so Mod R can just click Publish and then do the hard work of moderating.

To people asking about craft projects: I haven’t been able to knit or crochet because the hands are not cooperating. Especially the wrist rotation with the hook is a no go. I haven’t been able to see a neurologist either. I can’t even get on the schedule. It is a bit frustrating. Okay, it’s very frustrating.

I need to get back to workouts. I chickened out this week because we are having a heat wave. It’s overcast today and it cooled off to 96, wooo! We were at 101F (38C) yesterday. It’s hot and humid. I think lifting weights was helping a little or maybe it’s my imagination.

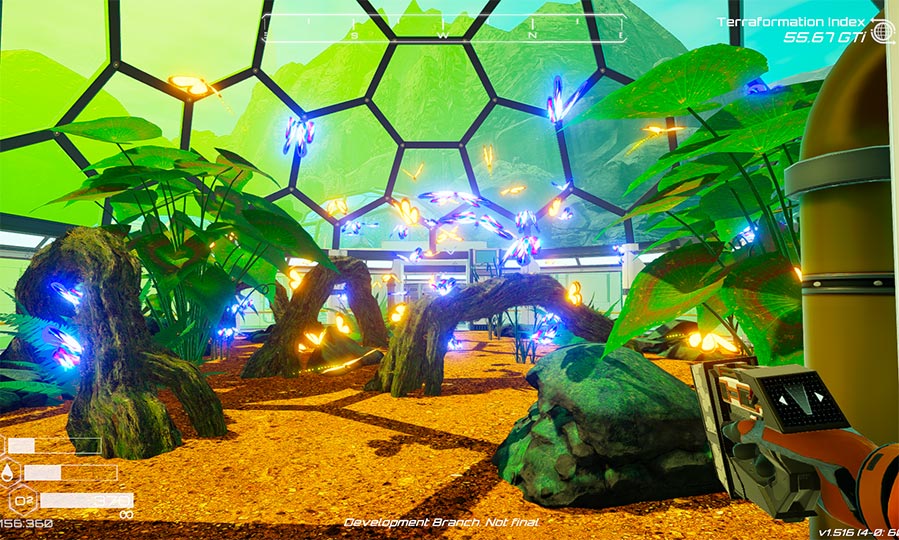

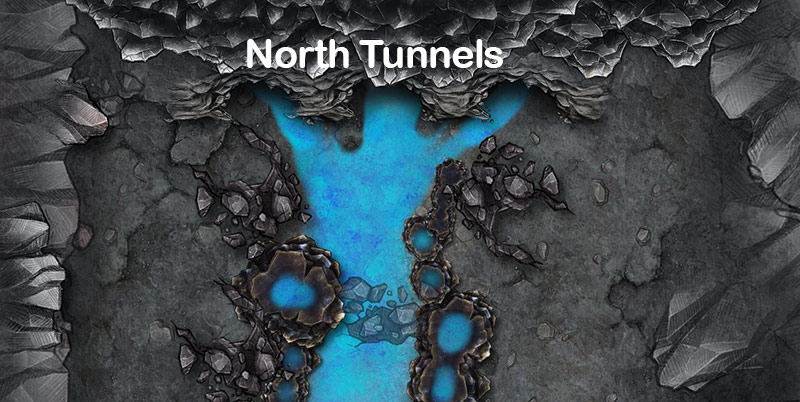

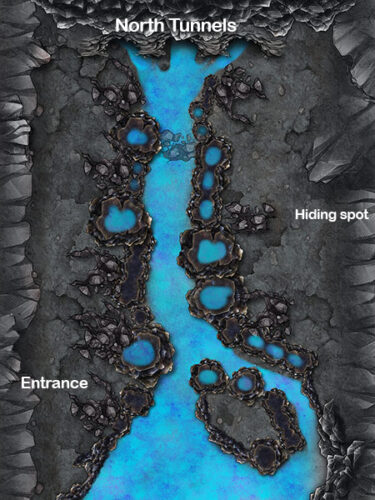

Since I can’t knit or crochet, I’ve been trying to play a little bit of computer games, although I have to limit that, too. Both Planet Crafter and the Enshrouded are releasing updates: the Enshrouded one already came out, and the Planet Crafter is coming on 16 or 19th.

I have been playing the Humble expansion in Planet Crafter in preparation for the expansion. It’s a neat game where you are a convict dropped off on a barren rock of a planet, and the only way to escape is to terraform it into a garden planet.

Right now I’m breeding butterflies in different colors. The game is pretty, although Humble isn’t my favorite. I like a lot of water at my base locations, and the centrally located lake is more like a puddle.

My butterflies!

My butterflies!

My bees!

My bees!

Zeolite crystal mining site

Zeolite crystal mining site

Cool Sinkhole. There is a cave behind the large waterfall.

Cool Sinkhole. There is a cave behind the large waterfall.

The new update is supposed to let you terraform more moons in this alien solar system. I’m excite!

Finally, we have gotten a couple of puzzled comments – mostly from international readers – regarding the widespread use of dishwashers in US. About 75% of US households have them. They are convenient, and we are encouraged to purchase them because they use less water. A typical modern dishwasher will use 3-4 gallons for a load of dishes, while washing the same load by hand uses 15-27 gallons. It also saves energy, because most people wash their dishes in hot water and heating that water adds up. To that one commenter who wondered why an off-the-grid home in the Southwest would need one – their water is likely limited. They are trying to conserve their resources. A small dishwasher can ran off solar, and washing dishes is not optional.

To the person who is now vigorously typing how their handwashing never uses that much water: Having a dishwasher doesn’t make you lazy, not having one doesn’t make you a dirty planet polluter. It’s a convenient appliance. Some people have space for it, some don’t, and there is no reason to have a moral superiority battle over it.

I’m trying to figure out what to read next. LitRPG is my new military SF. I usually read outside of the genre I’m working on and I’m unlikely to ever write a strict LitRPG. I am sadly out of the Azarinth Healer. I have Bushido Online in my library for some reason. Maybe I will try that one next.

The post Life and Other Dishes first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Magic Triumphs Sample Bonanza

Magic Triumphs, the final novel in the Kate Daniels main series, will be available in full dramatized audio from Graphic Audio on the 20th of May.

That’s eleven instalments (including Magic Gifts) of determination, heykittykittyness, blood, grit, immortal apple pie, and Atlanta mayhem, each one adapted with a full cast, original score, immersive sound effects, and enough snark to satisfy even Kate herself.

If you’ve never listened to a Graphic Audio adaptation before, it’s a full production, a “movie in your mind,” with actors voicing every character. Michael Glenn sacrificed vocal chords to roar like Curran. Nora Achrati basically became Kate, and adapted and directed every book with the same love we have for our favorite gal. KenYatta Rogers would get even Jim’s seal of approval. And the fights? You hear every bone crunch and magic burst.

Next Tuesday, the series will be complete, after a journey that became in 2023. Small Magics will be released with all the KD extras as well as original works like Retribution Clause, Grace of Small Magics, Of Swine and Roses on June 12th.

But wait … completed series doesn’t mean it’s OVER! Kate would never!

Exciting AnnouncementThe Wilmington Years series AND Blood Heir will both be getting the GA treatment, with Nora at the helm, in the first half of 2026!

Thank you to everyone who chalantly pressured fluffily suggested to GA that they continue adaptations in the Kate world and helped to make them audio cult classics.

The Horde is powerful, the Horde is mighty. The Horde, as usual, gets things done.

Until then, we’re celebrating with SIX exclusive audio clips from Magic Triumphs, more sample extravaganza than we’ve ever been able to share before!

A rude awakening:

Fear the Greeks, especially when they’re at your door in a panic:

I love him, you love him, but especially I love him, the best Dark Volhv of all:

Dum-dum-dum-DUUUUUUUMMM! The entrance, the drama, the llama!

It’s an impossible choice, but one of the best scenes of the series, I think. GO, DADDY!

Nobody likes nonconsensual dragons, dude!

Now it’s your turn: tell me which moment you’re most looking forward to from the dramatized Magic Triumphs?

The post Magic Triumphs Sample Bonanza first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Dishhhwashhher

My dearest BDH,

I come to this keyboard today to write to you that we are well. It has been 8 days without a working dishwasher. It is but by the grace of the higher power that we are surviving this crisis. Hope alone sustains us through these dark times, hope that a new dishwasher shall arrive today between the hours of 01:00 PM and 05:00 PM from Wilson Appliances.

Forever yours and deep in dishes,

Ilona, Your Loving Author.

The trouble with the dishwasher started as soon as we came back from vacation. After we got home, I marinated some chicken, and ended up with a load of dishes that had a big glass marinading dish in it.

I start the dishwasher. It gets through part of the cycle. I come back to the kitchen.

DRAIN.

Okay. I have done this song and dance before. I open the dishwasher full of nasty chicken water. Ugh. I get gloves, scoop the water out, take out the filter, clean it out – it’s clean, put it back in, hit the rinse and hold cycle.

DRAIN.

Grrr. I opened the dishwasher, scoop the nasty water out for the second time, remove filter, undo the plastic doohicky that protects a little fan. Sometimes stuff gets stuck under there, preventing the fan from rotating. The fan is clear. Nothing is stuck. Rinse and hold.

DRAIN.

*$##$%%^%$%^.

At that point it was late at night and I didn’t want to wrestle with the chicken water again, so I gave up.

Morning found Gordon messing with the dishwasher. He scooped the chicken water out, checked the filter, checked the fan.

DRAIN.

Maybe there was some grease accumulated somewhere and now things are clogged. We boil water, pour it into the dishwasher. The dishwasher drains. YES! Start the rinse and hold.

DRAIN.

More boiling water.

DRAIN.

DRAIN.

We hoped to have the dishwasher repaired, but nobody works on this brand. We did have a plumber out to check is the hose had clogged.

Plumber: It seems like the motor. How old is this dishwasher?

Gordon: 27 years.

Plumber: This might have something to do with your current problem.

So we bought a new dishwasher. In other news, I have finally finished the nobody knows how old bottle of Dawn’s dishwashing liquid that had been living alone in the dark under the sink.

The house is coming up on 30 years, and so far in the last 18 months the range quit, the fridge bit the dust, and now the dishwasher died.

::eyes the dual ovens::

Between you and me, if they die, I wouldn’t mind, because they are old and the temperature control is questionable. I’m pretty sure 375 is no longer 375. But we are keeping them until they die. They have got to hold on till the mid-fall at least. The Inheritance Buys New Ovens royalties should come in then.

Our smart thermostat quit, but we fixed it and Kid 1’s microwave gave up the ghost, so that concludes the trilogy of appliance breaking. These repairs usually come in threes, so let’s hope this cluster is behind us.

Here is hoping your appliances work well and last way past the manufacturer’s suggested lifecycle.

The post Dishhhwashhher first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Free Fiction Monday: Red Letter Day

Graduation Day at Barack Obama High School. The day the Red Letters arrive. The day that students get a glimpse into their own future.

But a handful never get a letter, and no one knows why. One teacher comes up with an idea though: a teacher who never got a Red Letter herself, a teacher finally finds the answers to her own fate.

Called “a fresh, solid, entertaining take on time travel” by Tangent Online, “Red Letter Day” was chosen as the best short story by the readers of Analog Magazine.

“Red Letter Day“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Red Letter Day By Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Graduation rehearsal—middle of the afternoon on the final Monday of the final week of school. The graduating seniors at Barack Obama High School gather in the gymnasium, get the wrapped packages with their robes (ordered long ago), their mortarboards, and their blue and white tassels. The tassels attract the most attention—everyone wants to know which side of the mortarboard to wear it on, and which side to move it to.

The future hovers, less than a week away, filled with possibilities.

Possibilities about to be limited, because it’s also Red Letter Day.

I stand on the platform, near the steps, not too far from the exit. I’m wearing my best business casual skirt today and a blouse that I no longer care about. I learned to wear something I didn’t like years ago; too many kids will cry on me by the end of the day, covering the blouse with slobber and makeup and aftershave.

My heart pounds. I’m a slender woman, although I’m told I’m formidable. Coaches need to be formidable. And while I still coach the basketball teams, I no longer teach gym classes because the folks in charge decided I’d be a better counselor than gym teacher. They made that decision on my first Red Letter Day at BOHS, more than twenty years ago.

I’m the only adult in this school who truly understands how horrible Red Letter Day can be. I think it’s cruel that Red Letter Day happens at all, but I think the cruelty gets compounded by the fact that it’s held in school.

Red Letter Day should be a holiday, so that kids are at home with their parents when the letters arrive.

Or don’t arrive, as the case may be.

And the problem is that we can’t even properly prepare for Red Letter Day. We can’t read the letters ahead of time: privacy laws prevent it.

So do the strict time travel rules. One contact—only one—through an emissary, who arrives shortly before rehearsal, stashes the envelopes in the practice binders, and then disappears again. The emissary carries actual letters from the future. The letters themselves are the old-fashioned paper kind, the kind people wrote 150 years ago, but write rarely now. Only the real letters, handwritten, on special paper get through. Real letters, so that the signatures can be verified, the paper guaranteed, the envelopes certified.

Apparently, even in the future, no one wants to make a mistake.

The binders have names written across them so the letter doesn’t go to the wrong person. And the letters are supposed to be deliberately vague.

I don’t deal with the kids who get letters. Others are here for that, some professional bullshitters—at least in my opinion. For a small fee, they’ll examine the writing, the signature, and try to clear up the letter’s deliberate vagueness, make a guess at the socio-economic status of the writer, the writer’s health, or mood.

I think that part of Red Letter Day makes it all a scam. But the schools go along with it, because the counselors (read: me) are busy with the kids who get no letter at all.

And we can’t predict whose letter won’t arrive. We don’t know until the kid stops mid-stride, opens the binder, and looks up with complete and utter shock.

Either there’s a red envelope inside or there’s nothing.

And we don’t even have time to check which binder is which.

***

I had my Red Letter Day thirty-two years ago, in the chapel of Sister Mary of Mercy High School in Shaker Heights, Ohio. Sister Mary of Mercy was a small co-ed Catholic High School, closed now, but very influential in its day. The best private school in Ohio according to some polls—controversial only because of its conservative politics and its willingness to indoctrinate its students.

I never noticed the indoctrination. I played basketball so well that I already had three full-ride scholarship offers from UCLA, UNLV, and Ohio State (home of the Buckeyes!). A pro scout promised I’d be a fifth round draft choice if only I went pro straight out of high school, but I wanted an education.

“You can get an education later,” he told me. “Any good school will let you in after you’ve made your money and had your fame.”

But I was brainy. I had studied athletes who went to the Bigs straight out of high school. Often they got injured, lost their contracts and their money, and never played again. Usually they had to take some crap job to pay for their college education—if, indeed, they went to college at all, which most of them never did.

Those who survived lost most of their earnings to managers, agents, and other hangers’ on. I knew what I didn’t know. I knew I was an ignorant kid with some great ball-handling ability. I knew that I was trusting and naïve and undereducated. And I knew that life extended well beyond thirty-five, when even the most gifted female athletes lost some of their edge.

I thought a lot about my future. I wondered about life past thirty-five. My future self, I knew, would write me a letter fifteen years after thirty-five. My future self, I believed, would tell me which path to follow, what decision to make.

I thought it all boiled down to college or the pros.

I had no idea there would be—there could be—anything else.

You see, anyone who wants to—anyone who feels so inclined—can write one single letter to their former self. The letter gets delivered just before high school graduation, when most teenagers are (theoretically) adults, but still under the protection of a school.

The recommendations on writing are that the letter should be inspiring. Or it should warn that former self away from a single person, a single event, or a one single choice.

Just one.

The statistics say that most folks don’t warn. They like their lives as lived. The folks motivated to write the letters wouldn’t change much, if anything.

It’s only those who’ve made a tragic mistake—one drunken night that led to a catastrophic accident, one bad decision that cost a best friend a life, one horrible sexual encounter that led to a lifetime of heartache—who write the explicit letter.

And the explicit letter leads to alternate universes. Lives veer off in all kinds of different paths. The adult who sends the letter hopes their former self will take their advice. If the former self does take the advice, then the kid who receives the letter from an adult they will never be. The kid, if smart, will become a different adult, the adult who somehow avoided that drunken night. That new adult will write a different letter to their former self, warning about another possibility or committing bland, vague prose about a glorious future.

There’re all kinds of scientific studies about this, all manner of debate about the consequences. All types of mandates, all sorts of rules.

And all of them lead back to that moment, that heart stopping moment that I experienced in the chapel of Sister Mary of Mercy High School, all those years ago.

We weren’t practicing graduation like the kids at Barack Obama High School. I don’t recall when we practiced graduation, although I’m sure we had a practice later in the week.

At Sister Mary of Mercy High School, we spent our Red Letter Day in prayer. All the students started their school days with Mass. But on Red Letter Day, the graduating seniors had to stay for a special service, marked by requests for God’s forgiveness and exhortations about the unnaturalness of what the law required Sister Mary of Mercy to do.

Sister Mary of Mercy High School loathed Red Letter Day. In fact, Sister Mary of Mercy High School, as an offshoot of the Catholic Church, opposed time travel altogether. Back in the dark ages (in other words, decades before I was born), the Catholic Church declared time travel an abomination, antithetical to God’s will.

You know the arguments: If God had wanted us to travel through time, the devout claim, he would have given us the ability to do so. If God had wanted us to travel through time, the scientists say, he would have given us the ability to understand time travel—and oh! Look! He’s done that.

Even now, the arguments devolve from there.

But time travel has become a fact of life for the rich and the powerful and the well-connected. The creation of alternate universes scares them less than the rest of us, I guess. Or maybe the rich really don’t care—they being different from you and I, as renowned (but little read) 20th Century American author F. Scott Fitzgerald so famously said.

The rest of us—the non-different ones—realized nearly a century ago that time travel for all was a dicey proposition, but this being America, we couldn’t deny people the opportunity of time travel.

Eventually time travel for everyone became a rallying cry. The liberals wanted government to fund it, and the conservatives felt only those who could afford it would be allowed to have it.

Then something bad happened—something not quite expunged from the history books, but something not taught in schools either (or at least the schools I went to), and the federal government came up with a compromise.

Everyone would get one free opportunity for time travel—not that they could actually go back and see the crucifixion or the Battle of Gettysburg—but that they could travel back in their own lives.

The possibility for massive change was so great, however, that the time travel had to be strictly controlled. All the regulations in the world wouldn’t stop someone who stood in Freedom Hall in July of 1776 from telling the Founding Fathers what they had wrought.

So the compromise got narrower and narrower (with the subtext being that the masses couldn’t be trusted with something as powerful as the ability to travel through time), and it finally became Red Letter Day, with all its rules and regulations. You’d have the ability to touch your own life without ever really leaving it. You’d reach back into your own past and reassure yourself, or put something right.

Which still seemed unnatural to the Catholics, the Southern Baptists, the Libertarians, and the Stuck in Time League (always my favorite, because they never did seem to understand the irony of their own name). For years after the law passed, places like Sister Mary of Mercy High School tried not to comply with it. They protested. They sued. They got sued.

Eventually, when the dust settled, they still had to comply.

But they didn’t have to like it.

So they tortured all of us, the poor hopeful graduating seniors, awaiting our future, awaiting our letters, awaiting our fate.

I remember the prayers. I remember kneeling for what seemed like hours. I remember the humidity of that late spring day, and the growing heat, because the chapel (a historical building) wasn’t allowed to have anything as unnatural as air conditioning.