Authors

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Benedict

In reply to Kevin.

There’s no such thing as a Primal sigl that increases your essentia count. There are ones that let you store personal essentia, which lets you simulate a higher essentia capacity, but you don’t get something for nothing – you have to pay that essentia in first (and it’ll de-attune quickly unless you do something to stop it). Also, if your plan is to use multiple sigls at once, you have to actually have enough channelling skill to make effective use of them, which a lot of people don’t.

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Kevin

In reply to Benedict.

Ah I should have clarified better!

I meant could you activate a strong enough Primal sigl to increase your essentia count, so you could activate three more. Thus using four activated sigls at once.

But I am guessing from your answer that is not feasible for most Drucrafters unless in cases where you have 2.8 or above Essentia Capacity where that is practical.

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Benedict

In reply to Kevin.

You can use as many sigls as you want – you can use ten if you like – but unless you’ve got a superhuman essentia capacity, you’re only going to have enough essentia to actually activate 2.5 to 3 of them at once, same as anyone else.

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Kevin

Very informative as always, with this info it makes me wonder if Tobias and Helen are using Essentia Capacity prejudice as an excuse for why they are not the heirs.

On the topic of Essentia Capacity, and since I love loophole abuses is it possible to use four sigls at once with one of them being a Primal sigl increasing essentia to “trick the body” as it were into thinking it can use three sigls?

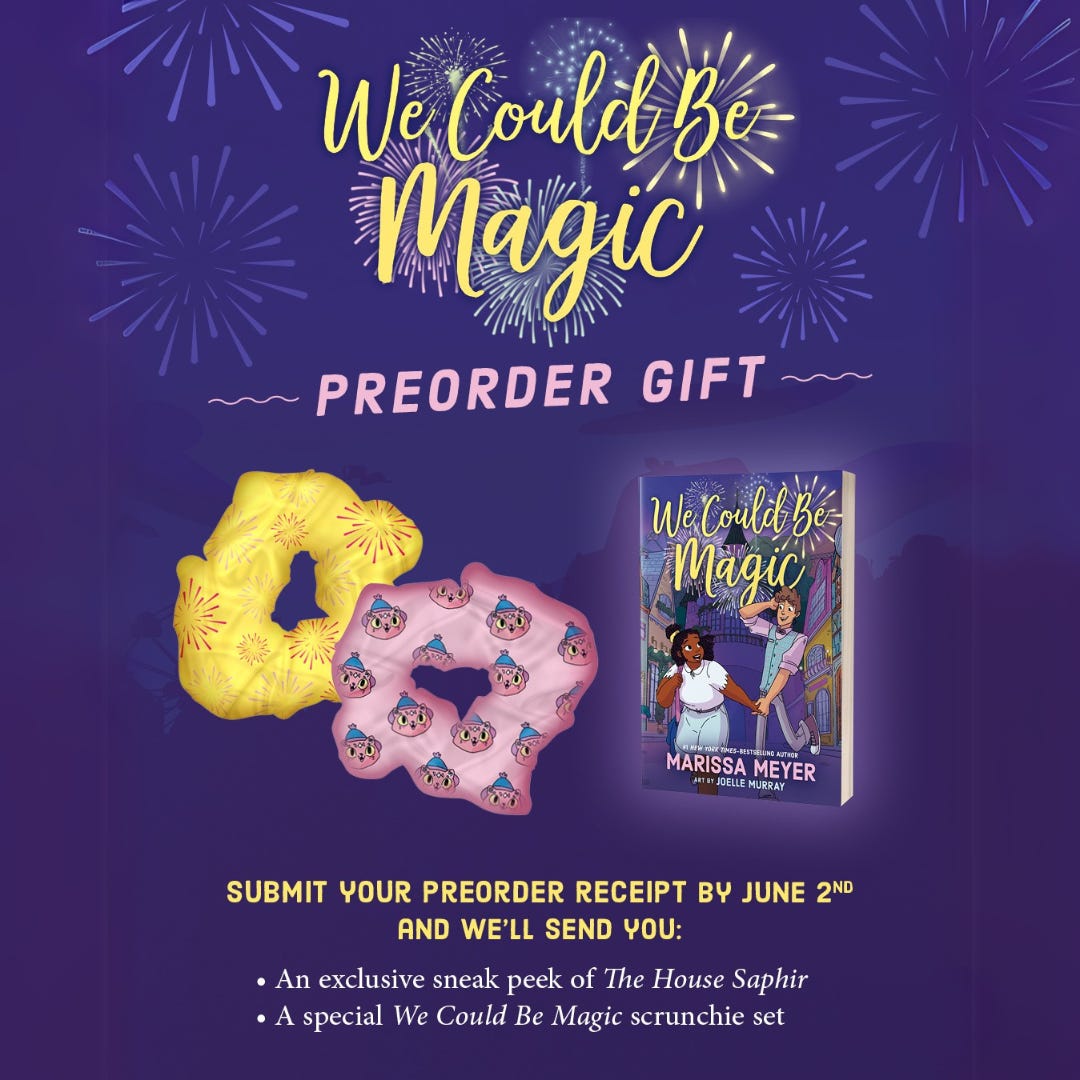

We Could Be Magic Tour, Preorder Goodies, and Upcoming Giveaways!

Happy Spring! It’s nearly time for the release of WE COULD BE MAGIC, my new swoony YA graphic novel, and I have goodies to share!

There is a preorder campaign going on now for readers in the US and Canada. Preorder your copy and upload your receipt to receive these special items below:

• An adorable scrunchie set inspired by the book

• An exclusive digital sneak peek of THE HOUSE SAPHIR (my next fairy tale retelling, coming out this fall!)

A swoon-worthy young adult graphic novel about a girl’s summer job at a theme park from #1 New York Times bestselling author Marissa Meyer.

When Tabitha Laurie was growing up, a visit to Sommerland saved her belief in true love, even as her parents’ marriage was falling apart. Now she’s landed her dream job at the theme park’s prestigious summer program, where she can make magical memories for other kids, guests, and superfans just like her. All she has to do is audition for one of the coveted princess roles, and soon her dreams will come true.

There’s just one problem. The heroes and heroines at Sommerland are all, well… thin. And no matter how much Tabi lives for the magic, she simply doesn’t fit the park’s idea of a princess.

Given a not-so-regal position at a nacho food stand instead, Tabi is going to need the support of new friends, a new crush, and a whole lot of magic if she’s going to devise her own happily ever after. . . without getting herself fired in the process.

With art by Joelle Murray, the wonder of Sommerland comes to life with charming characters and whimsical backdrops. We Could Be Magic is a perfect read for anyone looking to get swept away by a sparkly summer romance.

How to get your swag:

- Preorder your copy via my Bookshop.org store (or wherever you normally purchase your books).

- Submit your receipt here. US/Canada only. See link for full details.

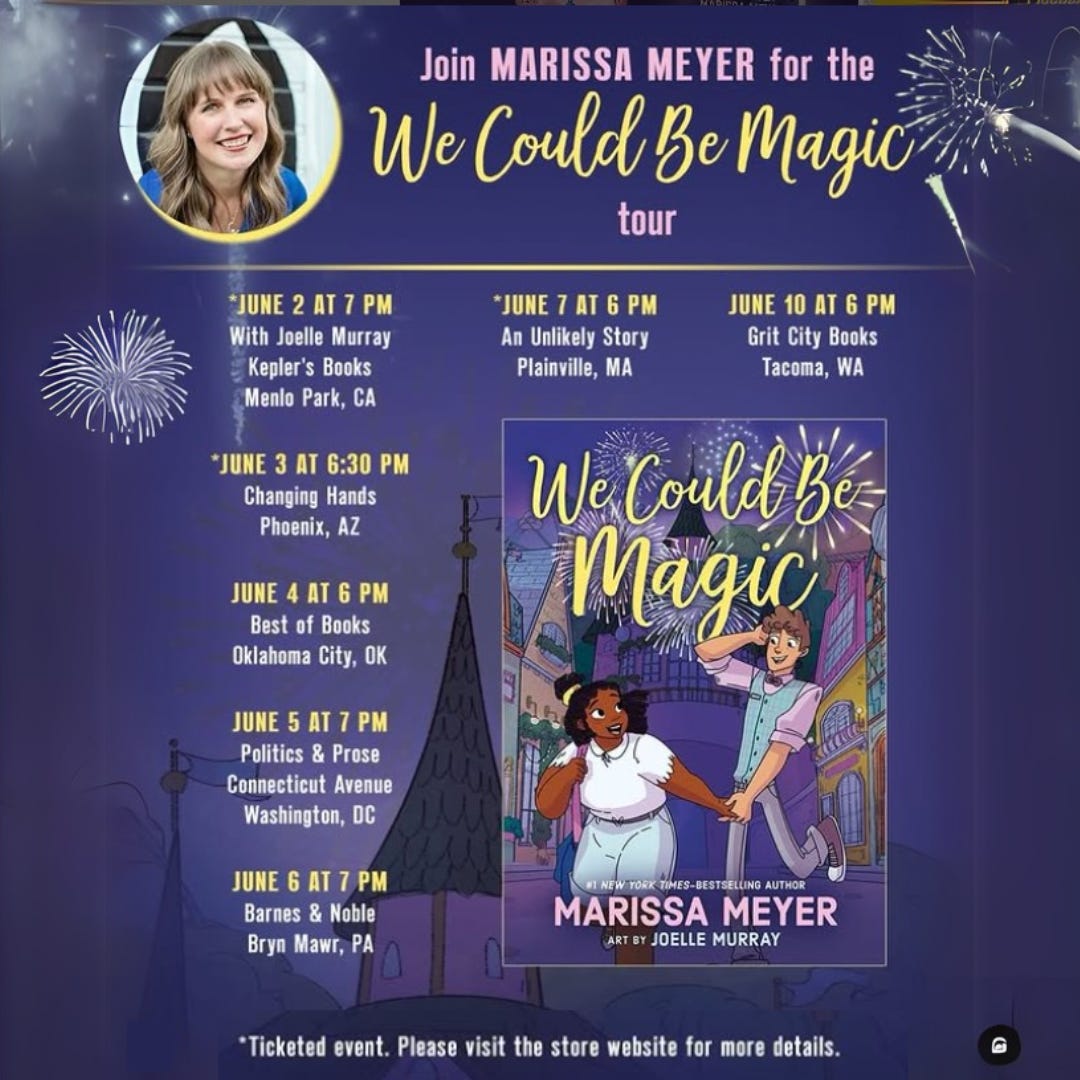

I’m going on tour and hope to see you!

See the special tour linktree for individual event details and ticketing.

The House Saphir

The House Saphir

I know many of you are anxiously awaiting THE HOUSE SAPHIR. Not only is there an exclusive sneak peek coming for those who preorder WE COULD BE MAGIC, but other giveaways are coming, including a romance inspired one over on Instagram, so make sure you follow me to get the latest.

THE HOUSE SAPHIR comes out November 4, but you can add it to Goodreads now and preorder your copy from my store at Bookshop.org (or wherever you get your books). Don’t forget to keep those receipts *hint, hint*.

Until next time, happy reading and I hope to see you soon on the WE COULD BE MAGIC tour!

With love,

Marissa

The post We Could Be Magic Tour, Preorder Goodies, and Upcoming Giveaways! first appeared on Marissa Meyer.

OUT NOW – The Counterfactual War

The Protectorate – an interdimensional empire that has conquered five timelines so far – has set its sights on ours. Led by a man willing to risk everything for power and conquest, armed with technology a hundred years ahead of ours – technology promising salvation to its allies and doom to its enemies – and drawing on a far deeper military history, the Protectorate Expeditionary Force has arrived to invade and incorporate our world into the greatest empire the multiverse has ever known, or die trying.

The United States has won a desperate battle against the crosstime invaders, but large swathes of the country remain under enemy occupation, the struggle to understand invader technology has barely begun and a new invasion force has appeared in the Middle East. As the country staggers and threatens to collapse, the military prepares for a major offensive that could make or break the war, while – deep in the heart of Texas – the invaders prepare a plan of their own …

One battle has been won. The war is far from over.

Download a FREE SAMPLE, then purchase from Amazon US, UK, CAN, AUS, Books2Read.

Back to Life, Back to Reality and Book Recommendation

The vacation was amazing. The air was 80F. The ocean was 80F. The pools were great. The room was spectacular. The food was delicious. The drinks were to die for.

We went on a date to this restaurant that was technically part of the resort but set outside of the grounds, by a busy street. We sat on a terrace, under a canvas, watched the foot traffic and listened to a remarkably good live singer. At some point I had a moment of wondering if this was actually happening. It’s been so long since we had a vacation. Last year, we had a weekend in Daytona. That was it. I needed this in the worst way.

We swam so much. I miss it already.

We are back home, and the dishwasher drainage line is clogged. We’ve taken the dishwasher apart, checked the fan, and have done the boiling water trick, so it looks like we have to get a plumber involved. Reality, coming like a freight train.

Professional NewsThis Kingdom is a hot potato. We have now sold the rights to 5 foreign countries, most of which we cannot contractually disclose yet, but we are free to say that we will be working with Tor UK. We are very excited.

We have seen the cover sketches. They sent 3 sketches and all three were great. We picked a favorite and can’t wait to see it in color and detail. I don’t want to jinx it, so I won’t say more.

Book RecommendationI usually don’t read while we work. It’s very hard to shift gears from concentrating on the narrative to enjoying it. While on vacation, though, I downloaded a series through Kindle Unlimited and I glomed it. I’ve read 4.5 books at this point. Big thanks to Matt, Alisha, Sauron, and Christy for recommending the Azarinth Healer series.

Ilea likes punching things. And eating.

Unfortunately, there aren’t too many career options for hungry brawlers. Instead, the plan is to quit her crappy fast-food job, go to college, and become a fully functioning member of society. Essentially – a fate worse than death.

So maybe it’s lucky that she wakes up one day in a strange world where a bunch of fantasy monsters are trying to kill her…?

On the bright side, ‘killing those monsters right back’ is now a viable career path! For she soon discovers her new home runs on a set of game-like rules that will allow her to punch things harder than in her wildest dreams. Well, maybe not her wildest dreams, but it’s close.

With no quest to follow, no guide to show her the way, and no real desire to be a Hero – Ilea embarks on a journey to discover a world full of magic. Magic she can use to fight even bigger monsters.

She’s struggling to survive, has no idea what will happen next, and is loving every minute of it. Except, and sometimes also, when she’s poisoned and/or has set herself on fire. It’s complicated.

Read the story that took Royal Road by storm with over 60 million views and counting.

It’s a classic LitRPG, the stats, the battles, the violence. A prefect beach read for me. I really enjoyed the action. The protagonist is endearing and is authentically a 20 year old. The world is imaginative and exciting. The Silver Rose dungeon was chef’s kiss. I’m a horrible harpy who hates everything, and I couldn’t stop reading it. If you like LitRPG, this is a good one.

For the romance readers: there is none. There is some casual sex with the door closed.

There is an audiobook and it is good. I listened to about half of the first one on the plane.

Fair warning for people fresh to the genre: this series concentrates a lot on the battles. You get very detailed blow by blow fights. I like battles and there were times my eyes started glazing over. Like if you think our fight scenes are too long, these are much more detailed.

Here is the link to Amazon: Azarinth Healer. There is always another drake.

The post Back to Life, Back to Reality and Book Recommendation first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

4 Mystery Novellas

I tend to write a lot of mystery novellas. They’re too long for traditional publishers, which makes them perfect for WMG. We can put the novellas in book form.

Over the last year, a number of you have asked how to get my Derringer-award winning novella, “Catherine The Great,” and while you can get it in last year’s Holiday Spectacular compilation, that’s only available in ebook. Many of you want paper…and I get it. I do too.

So, we decided to put it into paper. And by the time we got to that project, I had also written three other mystery/crime novellas. One is a thriller (Kizzie) and two are more straightforward mysteries. We put all four in a Kickstarter that launches today.

Here’s the video for the Kickstarter. Over the next week, I’ll also share the book trailers with you for the novellas. However, if you’d like to see them now, head to the Kickstarter. They’re all on it, along with a lot of other goodies.

As you can tell, this is one of my favorite things to write. I hope you end up getting the books.

https://kriswrites.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/4-Mystery-Novellas-Low-Res.mp4Polish publisher Vesper acquires The Providence Rider

Polish publisher Vesper has acquired the Polish translation rights to The Providence Rider. Vesper has published Polish translations of ten of Robert McCammon’s novels, so far, including Speaks the Nightbird (2022), The Queen of Bedlam (2023), and Mister Slaughter (2024).

Tuesday Musings: Our Child’s Birthday

Our beloved older daughter would have been thirty years old today.

Our beloved older daughter would have been thirty years old today.

Alexis Jordan Berner-Coe. Early on, it felt like a big name for such a tiny child. She was always the smallest in her class, the smallest on her team, the smallest in her dance recitals. We called her Alex. The head counselor at her first summer soccer camp called her “ABC” — for Alex Berner-Coe. The name stuck.

Later we realized that the name was too small to contain her, too simple to encompass all that she was, all that she would grow to be. She might have been the smallest in her class, but she was smart as hell and personable, with a huge, charismatic personality. She might have been the smallest on her teams, but she was fast and savvy and utterly fearless. On the soccer pitch and in the swimming pool, she was fierce and hard-working. Size didn’t matter. She might have been the smallest on stage, but she danced with passion and joy and grace, and, when appropriate, with a smile that blazed like burning magnesium.

Later we realized that the name was too small to contain her, too simple to encompass all that she was, all that she would grow to be. She might have been the smallest in her class, but she was smart as hell and personable, with a huge, charismatic personality. She might have been the smallest on her teams, but she was fast and savvy and utterly fearless. On the soccer pitch and in the swimming pool, she was fierce and hard-working. Size didn’t matter. She might have been the smallest on stage, but she danced with passion and joy and grace, and, when appropriate, with a smile that blazed like burning magnesium.

One time, in a soccer match against a hated rival, a player from the other team, a huge athlete nearly twice Alex’s size, grew tired of watching Alex’s back as she sped down the touchline on another break. So she fouled Alex. Hard. Slammed into her and sent her tumbling to the ground. I didn’t have time to worry about my kid. Because Alex bounced up while the ref’s whistle was still sounding, and wagged a finger at the girl. “Oh, no you don’t,” that finger-wag said. “You can’t intimidate me.”

One time, in a soccer match against a hated rival, a player from the other team, a huge athlete nearly twice Alex’s size, grew tired of watching Alex’s back as she sped down the touchline on another break. So she fouled Alex. Hard. Slammed into her and sent her tumbling to the ground. I didn’t have time to worry about my kid. Because Alex bounced up while the ref’s whistle was still sounding, and wagged a finger at the girl. “Oh, no you don’t,” that finger-wag said. “You can’t intimidate me.”

When she was in eighth grade, she decided to try out for the annual dance program at the university where Nancy worked. The program was called Perpetual Motion, and it was almost entirely student run. Each dance was choreographed by a student or group of students. They decided who they wanted in their dances and who they didn’t. The men and women in the program could easily have dismissed this thirteen-year-old as too young, too inexperienced, not really a part of the college. But instead, to their credit, they judged her on her dancing and maturity. She appeared in Perpetual Motion every year from eighth grade through twelfth, and we saw pretty much every performance. Not once did Alex ever seem out of place or beyond her depth.

She was effortlessly cool, like her uncle Bill — my oldest brother. And she had a wicked sense of humor. She was brilliant and beautiful. She loved to travel. She loved music and film and literature. She was passionate in her commitment to social justice. She adored her younger sister. And she was without a doubt the most courageous soul I have ever known.

She was effortlessly cool, like her uncle Bill — my oldest brother. And she had a wicked sense of humor. She was brilliant and beautiful. She loved to travel. She loved music and film and literature. She was passionate in her commitment to social justice. She adored her younger sister. And she was without a doubt the most courageous soul I have ever known.

When Alex was three years old, Nancy took a sabbatical semester in Quebec City, at the Université Laval. I stayed in Tennessee, where I was overseeing the construction of what would become our first home. Once Nancy found a place for them to live, I brought Alex up to her and helped the two of them settle in. In part, that meant finding a day-school for Alex so that Nancy could conduct her research. We put her in a Montessori school that seemed very nice, but was entirely French-speaking. The first morning, Alex was in tears, scared of a place she didn’t know, among people she could scarcely understand. But we knew she would love it eventually, and as young parents, we had decided this was best. So we explained to her as best we could that we would be back in a few hours, that the people there would take good care of her, and that this was something we needed for her to do. I will never forget walking away from the school, with tiny Alex standing at the window, tears streaming down her face as she waved goodbye to us. And I remember thinking then, “She is the bravest person I know.” Remember, Alex, all of three years old, didn’t speak a word of French!!

When Alex was three years old, Nancy took a sabbatical semester in Quebec City, at the Université Laval. I stayed in Tennessee, where I was overseeing the construction of what would become our first home. Once Nancy found a place for them to live, I brought Alex up to her and helped the two of them settle in. In part, that meant finding a day-school for Alex so that Nancy could conduct her research. We put her in a Montessori school that seemed very nice, but was entirely French-speaking. The first morning, Alex was in tears, scared of a place she didn’t know, among people she could scarcely understand. But we knew she would love it eventually, and as young parents, we had decided this was best. So we explained to her as best we could that we would be back in a few hours, that the people there would take good care of her, and that this was something we needed for her to do. I will never forget walking away from the school, with tiny Alex standing at the window, tears streaming down her face as she waved goodbye to us. And I remember thinking then, “She is the bravest person I know.” Remember, Alex, all of three years old, didn’t speak a word of French!!

Needless to say, when we returned that afternoon to take her home, she was having the time of her life. She’d already made a bunch of friends. She’d already charmed her two teachers. And, I kid you not, she had already picked up several French phrases, which she spoke with a perfect Quebecois accent.

Her dauntlessness served her well on the pitch and in the pool, on stage and in the classroom. It fed an adventuresome spirit that took her to Costa Rica for a semester in high school, to the top of Mount Rainier with a summer outdoor program, to a successful four years at NYU, to Germany for part of her sophomore year in college, to Spain for all of her junior year in college, and on countless side-trips all over Europe.

Her dauntlessness served her well on the pitch and in the pool, on stage and in the classroom. It fed an adventuresome spirit that took her to Costa Rica for a semester in high school, to the top of Mount Rainier with a summer outdoor program, to a successful four years at NYU, to Germany for part of her sophomore year in college, to Spain for all of her junior year in college, and on countless side-trips all over Europe.

And it allowed her to face the cancer that would eventually claim her life with remarkable strength, equanimity, and grace. She knew from the time of her diagnosis — a rare form of cervical cancer already at Stage 4 — that she faced long odds. I know that in private moments, and with her closest friends, she grieved for all that the disease would take from her. But she never allowed cancer to control her. She continued to work, to see friends and family, to travel, to go to movies and concerts and parties. She took classes. While undergoing chemo treatments, she turned her need for headscarves into a fashion statement. She lived her final years on her terms, refusing to wallow in self-pity because to do so would have meant sacrificing the joy for living that defined her.

She was, in short, remarkable. I loved her more than I can possibly say. I also admired her deeply. To this day, I push myself to do things that might make me uncomfortable or afraid by telling myself, “Alex would do it, and she’d want me to do it as well.”

She was, in short, remarkable. I loved her more than I can possibly say. I also admired her deeply. To this day, I push myself to do things that might make me uncomfortable or afraid by telling myself, “Alex would do it, and she’d want me to do it as well.”

She had twenty-eight and a half years, which wasn’t nearly enough. She did amazing things in that short time and could have done — should have been able to do — so very much more.

I miss her and think about her every minute of every day.

Happy birthday, my darling child. I love you to the moon and back.

Free Fiction Monday: Details

George has lived a full life as a decorated WWII veteran, high-end attorney, family man. But the incident that haunts him only took five minutes—five minutes when he shared a Coke with a woman on her way to California, a woman who would die hours later. Murdered. Maybe even by George.

Winner of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine’s Readers’ Choice Award.

“Details“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Details By Kristine Kathryn Rusch

No more alcohol, no more steak. In the end, it’s the little things that go, and you miss them like you miss a lover at odd times, at comfort times, at times when you need something small that means a whole lot more.

I’ve been thinking about the little things a lot since my granddaughter drove me to the glass-and-chrome hospital they built on the south side of town. Maybe it was the look the doctor gave me, the one that meant you should’ve listened to me, George. Maybe it was the sight of Flaherty’s, all made over into a diner.

Or maybe it’s the fact that I’m seventy-seven years old and not getting any younger. Every second becomes a detail then. An important one, and I can hear the details ticking away quicker than I would like.

It gets a man to thinking, all those details. I mentioned it to Sarah on the way back, and she said, in that dry way of hers, “Maybe you should write some of those details down.”

So I am.

* * *

I know Sarah wanted me to start with what she considers the beginning: my courting—and winning—of her grandmother. Then she’d want me to cover the early marriage, and of course the politics, all the way to the White House years.

But Flaherty’s got me thinking—details again—and Flaherty’s got me remembering.

They don’t make gas stations like that no more. You know the kind: the round-headed pumps, the Coke machine outside—the kind that dispenses bottles and has a bottle opener built in—and the concrete floor covered with gum and cigarette butts and oil so old it looks like it come out of the ground.

But Flaherty’s hasn’t been a gas station for a long time. For years it was closed up, the pumps gone, plywood over the windows. Then just last summer some kids from Vegas came in, bought the land, filled the pits, and made the place into a diner. For old folks like me, it looks strange—kinda like people being invited to eat in a service station—but everyone else thinks it looks authentic.

It isn’t.

The authentic Flaherty’s exists only in my mind now, and it won’t leave me alone. It never has. And so I’m starting with my most important memory of Flaherty’s—maybe my most important memory period—not because it’s the prettiest or even the best, but because it’s the one my brain sticks on, the one I see when I close my eyes at night and when I wake bleary eyed in the morning. It’s the one I mull over on sunny mornings, or catch myself daydreaming about as I take those walks the doctor has talked me into.

You’d think instead I’d focus on the look in Sally Anne’s eyes the first time I kissed her, or the way that pimply faced German boy moaned when he sank to his knees with my knife in his belly outside of Argentan.

But I don’t.

Instead, I think about Flaherty’s in the summer of 1946, and me fresh home from the war.

* * *

I got home from the war later than most.

Part of that was because of my age, and part of it was that I’d signed up for a second tour of duty, World War II being that kinda war, the kind where a man was expected to fight until the death, not like that police action in Korea, that strange mire we called Vietnam, or that video war them little boys fought in the Gulf.

I came back to McCardle in my uniform. I’d left a scrawny teenager, allowed to sign up because old Doc Elliot wanted to go himself and didn’t want to deny anyone anything, and I’d come back a twenty-five year old who’d killed his share of men, had his share of drunken nights, and slept with women who didn’t even know his name let alone speak his language. I’d seen Europe, even if much of it’d been bombed, and I knew how its food tasted, its people smelled, and its women smiled.

I was somebody different and I wanted the whole world to know.

The whole world, in those days, was McCardle, Nevada. My grandfather’d come west for the Comstock Load, but made his money selling dry goods, and when the Load petered, came to McCardle. He survived the resulting depression, and when the boom hit again around the turn of the century, he doubled his money. My father got into government early on, using the family fortune to control the town, and expected me to do the same.

When I came home, I wasn’t about to spend my whole life in Nevada. I had the GI Bill and a promise of a future, a future I planned on taking.

I had the summer free, and then in September, I’d be allowed to go East. I’d got accepted to Harvard, but I’d met some of those boys, and decided a pricey snobby school like that wasn’t a place for me. Instead, I went to Boston College because I’d heard of it and because it wasn’t as snobby and because it was far away.

It turned out to be an okay choice, but not the one I’d dreamed of. Nothing ever quite turns out like you dream.

I should’ve known that the day I drove into McCardle in ’46, but I didn’t. For years, I’d imagined myself coming back all spit-polished and shiny, the conquering hero. Instead I was covered in the dust that rolled into the windows of my ancient Ford truck, and the sweat that made my uniform cling to my skinny shoulders. The distance from Reno to McCardle seemed twice as long as it should have, and when I hit Clark County, I realized those short European distances had worked their way into my soul.

Back then, Clark County was so different as to be another country. Gambling had been legal since I was a boy, but it hadn’t become the business it is now. Bugsy Siegel’s dream in the desert, the Flamingo, wouldn’t be completed for another year, and while Vegas was going through a population boom the likes of which Nevadans hadn’t seen since the turn of the century, it wasn’t nowhere near Nevada’s biggest city.

McCardle got its share of soldiers and drifters and cons looking for a great break. Since gambling was in the hands of local and regional folks, its effects were different around the state. McCardle’s powers that be, including my father, took one look at Siegel and his ilk and knew them for what they were. Those boys couldn’t buy land, they couldn’t even get no one to talk to them, and they moved on to Vegas, which was farther from California, but much more willing to be bought. Years later, my father would brag that he stared down gangsters, but the truth of it was that the gangsters were looking for a quick buck and they knew that they’d be fighting unfriendlies in McCardle for generations when Vegas would have them for a song.

Nope. We had our casino, but our biggest business was divorces. For a short period after the war, McCardle was the divorce capitol of the US of A.

You sure could recognize the divorce folks. They’d come into town in their fancy cars, wearing too many or too few clothes, and then they’d go to McCardle’s only hotel, built by my grandfather’s dry goods money long about 1902, and they’d cart in enough luggage to last most people a year. Then they’d visit the casino, look for the local watering holes, and attempt to chat up a local or two for the requisite two weeks, and then they’d drive off, marriage irretrievably broken. Some would go back to Reno where they’d sign a new marriage license. Others would go about their business, never to be thought of again.

In those days, Flaherty’s was on the northern-eastern side of town, just at the edge of the buildings where the highway started its long trek toward forever. Now, Flaherty’s is dead center. But in those days, it was the first sign you were coming into civilization, that and the way the city spread before you like a vision. You had about five minutes of steady driving after you left Flaherty’s before you hit the main part of McCardle, and I decided, on that hot afternoon, that five minutes was five too many.

I pulled into Flaherty’s and used one thin dime to buy myself an ice-cold Coca-Cola.

I remember it as if it happened an hour ago: getting out of that Ford, my uniform sticking to my legs, the sweat pouring down my chest and back, the grit of sand in my eyes. I walked past several cars to get to the concrete slab they’d built Flaherty’s on. A bell ting-tinged near me as someone’s tank got filled, and in the cool darkness of the station proper, a little bell pinged before the cash register popped open. Flaherty himself stood behind the register in those days, although like as not by ’46, you’d find him drunk.

The place smelled of gasoline and motor oil. A greasy Philco perched on a metal filing cabinet near the cash register, and it was broadcasting teen idol Frankie Sinatra live, a pack of screaming girls ruining the song. In the bay, a green car was half disassembled, the legs of some poor kid sticking out from under its side as he worked underneath. Another mechanic, a guy named Jed, a tough who’d been a few years behind me in school, leaned into the hood. I remembered Jed real well. Rumor had it he’d knifed an Indian near a roadside stand. I’d stopped him from hitting one of the girls in my class when she’d laughed at him for asking her on a date. After that, Jed and I avoided each other when we could and were coldly polite when we couldn’t.

The Coke bottle—one of the small ones that they don’t make any more—popped out of the machine. I grabbed its cold wet sides, and used the built-in bottle opener to pop the lid. Brown fizz streamed out the top, and I bent to catch as much of it as I could without getting it on my uniform.

The Coke was ice-cold and delicious, even if I was drinking foam. In those days, Coke was sweet and lemony and just about the best non-alcoholic drink money could buy. I finished the bottle in several long gulps, then dug in my pocket for another dime. I hadn’t realized how thirsty I was or how tired; being this close to home brought out every little ache, even the ones I had no idea that I had. I stuck the dime in the machine, and took my second bottle, this time waiting until the contents settled before opening it.

“Hey, soldier. Mind if I have a sip?”

The voice was sultry and sexy and very female. I jumped just a little at the sound. I hadn’t seen anyone besides Flaherty and the grease monkeys inside, even though I had known, on some level, that other folks were around me. I kept a two-fingered grip on the chilly bottle as I looked up.

A woman was leaning against the building. She wore a checked blouse tied beneath her breasts, tight pants that gathered around her calves, and Keds. She finished off an unfiltered cigarette and flicked it with her thumb and forefinger into the sand on the building’s far side. Her hair was a brownish red, her skin so dark it made me wonder if she were a devotee of that crazy new fad that had women lying in the sun all hours trying to get tan. Her eyes were coal-black but her features were delicate, almost as if someone had taken the image from a Dresden doll and changed its coloring to something else entirely.

“Well?” she said. “I’m outta dimes.”

I opened the bottle and handed it to her. She put its mouth between those lips and sucked. I felt a shiver run down my back. For a moment, it felt as if I hadn’t left Italy.

Then she pulled the bottle down, handed it back to me, and wiped the condensation on her thighs. “Thanks,” she said. “I was getting thirsty.”

“That your car in there?” I managed.

She nodded. “It made lots of pretty blue smoke and a helluva groan when I tried to start it up. And here I thought it only needed gas.”

Her laugh was deep and self-deprecating, but beneath it I thought I heard fear.

“How long they been working on it?”

“Most of the day,” she said. “God knows how much it’s going to cost.”

“Have you asked?”

“Sure.” She held out her hand, and I gave the bottle back to her, even though I hadn’t yet taken a drink. “They don’t know either.”

She tipped the bottle back and took another swig. I watched her drink and so did most of the men in the place. Jed was leaning on the car, his face half hidden in the shadows. I could sense rather than see his expression. It was that same flatness I’d seen just before he lit into the girl outside school. I didn’t know if I was causing the look just by being there, or if he’d already made a pass at this woman, and failed.

“You’re not from McCardle,” I said.

She wiped her mouth with the back of her hand, and gave the bottle back to me. “Does it show?” she asked, grinning.

The grin transformed all her strange features, making her into one of the most beautiful women I’d ever seen. I took a sip from the bottle simply to buy myself some time, and tasted her on the glass rim. Suddenly it seemed as if the heat of the day had grown more intense. I drank more than I intended, and pulled the bottle away only when my body threatened to burp the liquid back up.

“You just visiting?” I asked which was the only way I could get the answer I really wanted. She wasn’t wearing a ring; I suspected she was here for a quickie divorce.

“Taking in the sights, starting with Flaherty’s here,” she said. “Anything else I shouldn’t miss?”

I almost answered her seriously before I caught that grin again. “There’s not much to the place,” I said.

“Except a soldier boy, going home,” she said.

“Does it show?” I asked and we both laughed. Then I finished the second bottle, put it in the wooden crate with the first, and flipped her a dime.

“The next one’s on me,” I said, as I made my way back to the Ford.

“You’re the first hospitable person I’ve met here,” she said and I should’ve heard it then, that plea, that subtle request for help.

Instead, I smiled. “I’m sure you’ll meet others,” I said and left.

* * *

Kinda strange I can remember it detail for detail, word for word. If I close my eyes and concentrate, the taste of her mingled with Coke comes back as if I had just experienced it; the way her laugh rasped and the sultry warmth of her voice are just outside my earshot.

Only now the memory has layers: the way I felt it, the way I remembered it at various times in my life, and the understanding I have now.

None of it changes anything.

It can’t.

No matter what, she’s still dead.

* * *

I was asleep when Sheriff Conner showed up at the door at ten a.m. two mornings later. I was usually up with the dawn, but after two nights in my childhood bed, I’d finally found a way to be comfortable. Seems the bed was child-sized, and I had grown several inches in my four years away. The bed was a sign to me that I didn’t have long in my parents’ home, and I knew it. I didn’t belong here anyway. I was an adult full grown, a man who’d spent his time away from home. Trying to fit in around these people was like trying to sleep in my old bed: every time I moved I realized I had grown beyond them.

When Sheriff Conner arrived, my mother woke me with a sharp shake of the shoulder. She frowned at me, as if I had embarrassed her, and then she vanished from my room. I pulled on a pair of khakis that were wrinkled from my overnight case, and combed my hair with my fingers. I grabbed a shirt as I wandered barefoot into the living room.

Sheriff Conner was a big man with skin that turned beet-red in the Nevada sun. His blond hair was cropped so short that the top of his head sunburned. He hadn’t changed since I was a boy. He was still too large for his uniform, and his watch dug red lines into the flesh of his wrist. I always wondered how he could be comfortable in those tight clothes in that heat, but, except for the dots of perspiration around his face, he never seemed to notice.

“You grew some,” he said as the screen door slammed behind my mother.

“Yep,” I said.

“Your folks say you saw action.”

“A bit.”

He grunted and his bright blue eyes skittered away from mine. In that moment, I realized he had been too young for World War I, and too old for this war, and he was one of those men who wanted to serve, no matter what the cause. I wasn’t that kind of man, only I learned it later when I contemplated Korea and the mess we were making there.

“I guess you just got to town,” he said.

“Two days ago.”

“And when you drove in, you stopped at Flaherty’s first, but didn’t get no gas.” His tone had gotten sharper. He was easing into the questions he felt he needed to ask me.

“I was thirsty. It’s a long drive across that desert.”

He smiled then, revealing a missing tooth on his upper left side. “You bought a soda.”

“Two,” I said.

“And shared one.”

So that was it. Something to do with the girl. I stiffened, waiting. Sometimes girls who came onto a man like that didn’t like the rejection. I hadn’t gone looking for her over to the hotel. Maybe she had taken offense and told a lie or two about me. Or maybe her soon-to-be ex-husband had finally arrived and had taken an instant dislike to me. Maybe Sheriff Conner had come to warn me about that.

“You make it your policy to share your drinks with a nigra?”

“Excuse me?” I asked. I could lie now and say I was shocked at his word choice, but this was 1946, long before political correctness came into vogue, almost a decade before the official start of the Civil Rights movement, although the seeds of it were in the air.

No. I wasn’t shocked because of his language. I was shocked at myself. I was shocked that I had shared a drink with a black woman—although in those days, I probably would have called her colored not to give too much offense.

“A whole buncha people saw you talk to her, share a Coke with her, and buy her another one. A few said it looked like there was an attraction. Couple others coulda sworn you was flirting.”

I had been flirting. I hadn’t seen her as black—and yes, back then, it would have made a difference to me. I’ve learned a lot about racial tolerance since, and a lot more about intolerance. I wasn’t an offensive racist in those days, just a passive one. A man who kept to his own side of the street and didn’t mingle, just as he was supposed to do.

I would never have flirted if I had known. No matter how beautiful she was. But that hair, those features all belied what I had been taught. I had thought the darkness of her skin due to tanning not to heredity.

I had seen what I had wanted to see.

Sheriff Conner was watching me think. God knows what kind of expressions had crossed my face, but whatever they were, they weren’t good.

“Well?” he asked.

“Is it against the law now to buy a woman a drink on a hot summer day?” I asked.

“Might be,” he said, “if that woman shows up dead the next day.”

“Dead?” I whispered.

He nodded.

“I never saw her before,” I said.

“So you usually just go up and share a drink with a nigra woman you never met.”

“I didn’t know she was colored,” I said.

He raised his eyebrows at me.

“She was in the shade,” I said and realized how weak that sounded.

The Sheriff laughed. “And all pussy’s the same in the dark, ain’t it?” he said, and slapped my leg. I’d heard worse, much worse, in the army but it didn’t shock me like he just had. I’d never heard Sheriff Conner be crude, although my father always said he was. Apparently the Sheriff was only crude to adults. To children he was the model of decorum.

I wasn’t a child any longer.

“How’d she die?” I asked.

“Blow to the head.”

“At the station?”

“In the desert. Her pants was gone, and that scrap of fabric that passed for a blouse was underneath her.”

The desert. Someone had to take her there. I felt myself go cold.

“I didn’t know her,” I said, and if she had been a white woman, he might have believed me. But in McCardle, in those years and before, a man like me didn’t flirt with—hell, a man like me didn’t talk to—a woman like her.

“Then what was she doing here?” he asked.

“Getting a divorce?”

“Girls like her don’t get a divorce.”

That rankled me, even then. “So what do they do?”

He didn’t answer. “She wasn’t here for no divorce.”

“Have you investigated it?”

“Hell, no. Can’t even find her purse.”‘

“Well, did you trace the license on the car?”

He frowned at me then. “What car?”

“The ones the guys were fixing, the green car. They had it nearly taken apart.”

“And it was hers?”

“That’s what she said.” At least, that was what I thought she said. I suddenly couldn’t remember her exact words, although they would come to me later.

The whole scene would come to me later, like it was something I made up, like a dream that was only half there upon waking and then came, full-blown and unbidden, into the mind.

That your car? I said to her, and she didn’t answer, at least not directly. She didn’t say yes or no.

“Did you check with the boys at the station?” I asked.

“They didn’t say nothing about a car.”

“Did you ask Jed?”

The sheriff frowned at me. I’d forgotten until then that he and Jed were drinking buddies. “Yeah, of course I did.”

“Well, I can’t be the only one to remember it,” I said. “They had it torn apart.”

“Izzat so?” he asked, stroking his chin. “You think that’s important?”

“If it tells you who she is, it is,” I said, a bit stunned at his denseness.

“Maybe,” he said, but he didn’t seem to be thinking of that. He seemed focused on something else altogether. The look that crossed his face was half sad, half worried. Then he heaved himself out of the chair, and left without even a good-bye.

I sat on the sofa, wondering what, exactly, that all meant. I was still shaken by my own blindness, and by the Sheriff’s willingness to accuse me of a crime that seemed impossible to me.

It seemed impossible that a woman that vibrant could be dead.

It seemed impossible that a woman that vibrant had been black.

It seemed impossible, but there it was. It startled me.

I was more shocked at her color than at her death.

And that was the hell of it.

* * *

I tried not to think of it.

I’d learned how to do that during the war—it’s what helped me survive Normandy—and it had been effective during my tour.

But it stopped working about a week later when her family showed up.

They came for the body, and they seemed a lot more out of place than she had. Her father was a big man, the kind most folks in McCardle would have crossed the street to avoid or would have bullied out of fear. Her mother was delicate, with the same Dresden features as her daughter but on much darker skin. The auburn hair didn’t seem to come from either of them.

And with them was her husband. He wore a uniform, like I did, and his eyes were red as if he’d been crying for a long, long time. I saw them come out of the mortuary, the parents with their arms around each other, the husband walking alone.

The husband threw me, and made me even more uncomfortable than I had already been.

I thought she had flirted with me.

I usually didn’t mistake those things.

But, it seemed, I made a whole lot of mistakes in that short half hour I had known her.

They drove out that night with her body in the back of their truck. I knew that because my conscience forced me over to the hotel to talk to them, to ask them about the green car, and to tell them I was sorry.

When I got there, I learned that the only hotel in McCardle—my family’s hotel—didn’t take their kind. Maybe that, more than an assumption, explained the Sheriff’s remark: Girls like her didn’t get a divorce.

Maybe they didn’t, at least not in McCardle, because the town made sure they couldn’t, unless they had some place to stay.

And there weren’t blacks in McCardle then. The blacks didn’t start arriving for another year.

* * *

The next day, I moved, over my mother’s protests, into my own apartment. It was a single room with a hot plate and a small icebox over the town’s only restaurant. I shared a bathroom with three other tenants, and counted myself fortunate to have two windows. The place came furnished, and the Murphy bed was long enough for me, although even with fans I had trouble sleeping. The building kept the heat of the day, and not even the temperature drop after sunset could ease it. On those unbearable summer nights, I lay in tangled sheets, the smell of greasy hamburgers and chicken-fried steak carried on the breeze. I counted it better than being at home.

Especially after the nightmares started.

Strangely they weren’t about her. Nor were they about the war. I didn’t have nightmares about that war for twenty years, not until I started seeing images from Vietnam on television. Then a different set of nightmares came, and I went to the VA where I was diagnosed with a delayed stress reaction and given a whole passel of drugs that I eventually pitched.

No. Those early nightmares were about him. Her husband. The man with the olive green uniform and the red eyes. I knew guys like him. They walked with their backs straight, their faces impassive. They didn’t move unless they had to, and they never talked back, and if they showed emotion, it was because they thought guys like me weren’t looking.

He hadn’t cared about hiding any more. His emotion had been too deep.

And once Sheriff Conner figured out I had nothing to do with it, he’d declared the case closed. Over dinner the night before I left, my father speculated that Conner’d just shown up to show my father who was boss. Mother’d ventured that Conner hoped I was guilty, so it’d bring down the whole power structure of the town.

Instead, I think, it just brought Conner down. He was out of office by the following year, and the year after that he was dead, a victim of a slow-speed single vehicle drunken car crash in the days before seat belts.

I think no one would have known what happened if it hadn’t been for those nightmares. I’d dream in that dry, dry heat of him just standing there, looking at me, eyes red, face impassive. Her body was in the green car beside us, and he would stare at me, as if I knew something, as if I were keeping something from him.

But how could I have known anything? I’d shared a Coke with her and gone on.

I hadn’t even bothered to learn her name.

* * *

In the sixties they called what I was feeling white liberal guilt. Not that I had done anything wrong, mind you, but if I had known what she was—who she was—I would have acted differently. I knew it, and it bothered me.

It almost bothered me more than the fact she was dead.

Although that bothered me too. That, and the dreams. And the green car.

I went to Flaherty’s soon after the dreams started and filled up my tank. I got myself another Coke and I stared at the spot where I had seen her. The shadows were dark there, but not that dark. The air was cool but not that cool, and only someone who was waiting for a car would choose to wait in that spot, on that day, with a real town nearby. She must have been real thirsty to ask me for a drink.

Real thirsty and real scared.

And maybe she took one look at my uniform, and thought I’d be able to help her.

She even tried to ask.

You’re the first hospitable person I’ve met here, she’d said.

I’m sure you’ll meet others.

What she must have thought of that sentence.

How wrong I’d been.

I took my Coke and walked around the place, seeing lots of cars half finished, and even more car parts, but nothing of that particular shade of green.

Her family had taken her home in a truck.

The car was missing.

And as I leaned on the back of that brick building, the bottle cold in my hand, I wondered. Had the mechanics started working on the car because they too hadn’t realized who she was? Had she gotten all the way to Nevada traveling white highways and hiding her darker-than-expected skin under a trail of moxie?

I went into the mechanic’s bay, and Jed was there, putting oil into a 1937 Ford truck that had seen better days. A younger man stood beside him, and I wagered from the cut of his pants and the constant movement of his feet, that he’d been the guy under the car that day.

I leaned against the wall, sipping my Coke, and watched them.

They got quiet when they saw me. I grinned at them. I wasn’t wearing my uniform that day, just a pair of grimy dungarees and a t-shirt. Even so, I was hot and miserable, and probably looked it.

I tilted my bottle toward them in a kinda salute. The younger man, the one I didn’t recognize, nodded back.

“You seen that girl the other day?” I asked. I might have said more. I try not to remember. I can’t believe the language we used then: Japs and niggers and wops; the way we got gypped or jewed down; laughing at the pansies and whistling at the dames. And we didn’t think nothing of it, at least I didn’t. Each word had to be unlearned, just as—I guess—it had to be learned.

Jed put a hand on his friend’s arm, a small subtle movement I almost didn’t see. “Why’re you askin’?” And I could feel it, that old antipathy between us. Every word we’d ever exchanged, every look we had was buried in those words.

He wouldn’t talk to me, not really. He wouldn’t tell me what I needed to know. But his friend might. I had to play that at least.

“I was wondering if she’s living around here.” I said with an intentional leer.

“You don’t know?” the younger asked.

My heart triple-hammered. I knew then that the sheriff hadn’t told anyone he’d come after me. “Know what?”

“They found her in the desert with her face bashed in.”

“Jesus,” I said softly, then whistled for good measure. “What happened?”

“Dunno,” Jed said, his hand squeezing the other boy’s arm. Jed saw my gaze drop to his fingers, and then go back to his face. He grinned, like we were sharing a secret. And I didn’t like what I was thinking.

It seemed simple. Too simple. Impossibly simple. A man couldn’t just sense that another man had done something wrong. He needed proof.

“Too damn bad,” I said, taking another swig of my Coke. “I woulda liked a piece of that.”

“You and half the town,” the younger one said, and laughed nervously.

Jed didn’t laugh with him, but stared at me with narrowed green eyes. “I can’t believe you didn’t hear of it,” he said. “The whole town’s been talking.”

I shrugged. “Maybe I wasn’t listening.” I set the Coke down beside the radio and scanned the bay. “What’re they gonna do with that car of hers? Sell it?”

“Ain’t no one found it,” the younger boy said.

“She drove it outta here?” I asked. “She said it seemed hopeless.”

Finally Jed grinned. He actually looked merry, as if we were talking about the weather instead of a murder. “Women always say that.”

I didn’t smile back. “What was wrong with it?”

“You name it,” the younger one said. “She’d driven that thing to death.”

I knew one more question would be too many, but I couldn’t stop myself. “She say why?”

“You gotta reason for all this interest, George?” Jed asked. “You can’t get nothing from her now.”

“Guess not,” I said. “Just seems curious somehow. Woman comes here, to this town, and ends up dead.”

“Don’t seem curious to me,” Jed said. “She didn’t belong here.”

I stared at him a moment. “People don’t belong a lotta places but that don’t mean they need to die.”

He shrugged and turned away, ending the conversation. I picked up my Coke bottle. It had gotten warm already. I took another sip, letting the sweet lemony taste and the carbonation make up for the lack of coolness.

Then I went outside.

What did I want with all this? To get rid of some guilt? To make the dreams go away?

I didn’t know, and it angered me.

“Hey.” It was the younger one. He’d come out into the sun, ostensibly to smoke. He lit up a Chesterfield and offered me one. I took it to be companionable, and we lit off the same match.

Jed peeked out of the bay and watched for a moment, then disappeared, apparently satisfied that nothing was going to be said, probably thinking he had the kid under his thumb. Only Jed was wrong.

The younger one spoke softly, so softly I had to strain to hear, and I was standing next to him. “She said she was driving from Mississippi to California to join her husband. Said he’d got back from Europe and got a job in some plant in Los Angeles. Said they’d make good money there, but they didn’t have it now, and could we do as little as possible on the car, so that it’d be cheap.”

“Did you?” I asked. And when he looked confused, I added for clarification, “Keep it cheap?”

He took a long drag off the cigarette, and let the smoke out his nose. “We didn’t finish,” he said.

I felt that triple-hammer again. A little bit of adrenaline, something to let me know that I was going somewhere. “So where’s the car?”

“We left it in the bay. Next morning, we come back and it’s gone. Jed, there, he cusses her out, says all them people are like that, you can’t trust ’em for nothing, and that was that. Till the sheriff showed up, saying she was dead.”

The car I saw couldn’t have been driven, and the woman I saw couldn’t have fixed it. She would not have stopped here if she could.

“You left the car in pieces?” I asked. “And it was gone the next day? Someone drove it out of here?”

He shrugged. “Guess they finished it.”

“That would’ve taken some know-how, wouldn’t it?”

“Some,” he said. He flicked his cigarette butt onto the sandy gravel. I glanced up. Jed was staring us from the bay. I felt the hair on the back of my neck rise.

I took another drag off my cigarette and watched a heat shimmer work its way down the highway. The boy started walking away from me.

“Where was she?” I asked. “When you left? Where was she?”

And I think he knew then that my interest wasn’t really casual. Up until that point, he could have pretended it was. But at that moment, he knew.

“I dunno,” he said, and his voice was flat.

“Sure you do,” I said. I spoke softly so Jed couldn’t overhear me.

The man looked at my face. His had turned bright red, and beads of sweat I hadn’t noticed earlier were dotting his skin. “I—left her outside. Near the Coke machine.”

With a car that didn’t run, and no place to take her in for the night.

“Did you offer to give her a lift somewhere?”

He shook his head.

“Was the station still open when you left?”

“For another hour,” he said.

“Did you tell the sheriff this?”

He shook his head again.

“Why not?”

He glanced at Jed, who had crossed his arms and was leaning against the bay doors. “I didn’t think it was none of his business,” the boy whispered.

“You didn’t think, or Jed there, he didn’t think.”

“Neither of us,” the boy said. “Jed told her she could sleep in there by the car. But it woulda been an oven, even during the night. I think she knew that.”

“Is that where she slept?”

“I dunno.” This time the boy did not meet my gaze. Sweat ran off his forehead, onto his chin, and dripped on his shirt. He didn’t know, and he was sorry.

And so was I.

If I was going to pursue this logically, then I had to think logically. And it seemed to me that whoever killed the girl had known about the car. I couldn’t believe she would have talked to anyone else—I suspected she only spoke to me because I was in uniform. And if I made that assumption, then the only other people who would have known about her, about the car, about the entire business were the people who worked the station.

“Who was working that night?” I asked.

“Mr. Flaherty,” he said.

Mr. Flaherty. Mac Flaherty, whom I’d known since I was a boy. He was a hard decent man who expected work out of his employees, payment from his customers, and good money for a job well done. I’d seen Mac Flaherty in his station, at church, and at school getting his son, and I couldn’t believe he had killed someone.

But then, I had. I had killed a lot of boys overseas, and I would have killed more if Hitler hadn’t proved he was a coward and did the world a favor by dying by his own hand.

And the Mac Flaherty who ran the station now wasn’t the same man as the one I’d known. I’d learned that much in my few short days in McCardle.

A shiver ran down my back. Then I headed inside, looking for Mac Flaherty, and finding him.

* * *

Mac Flaherty was drunk. Not falling down, noticeable drunk, but his daily drunk, the kind that made a man a bit blurry around the edges, kept him from feeling the pain of day-to-day living, and kept him working a job he no longer liked.

Once Flaherty’d loved his work. It had been obvious in the booming way he’d greet new customers, in the smile he wore every day whether going or coming from work.

But then he left for the war, like I did, only he came back in ’43 minus three fingers on his left hand to find his wife shacking up with the local undertaker, and a half-sibling for his son baking in the oven. The wife, not him, took advantage of the McCardle’s divorce laws, and Flaherty was never the same. She and the undertaker left that week, and apparently, Flaherty never saw his kid again.

I went inside the service station’s main area, and the smell of beer mixed with the stench of gasoline. Flaherty was clutching a can, staring at me.

“You harassing the kid?” he asked.

“No,” I said, even though I felt that wasn’t entirely true. “I was just curious about the woman who died.”

“She something to you?” Flaherty asked.

“Only met her the once,” I said.

“Then what’s the interest?”

“I don’t know,” I said, and we both seemed surprised by my honesty. “Your boy says he left her sitting outside. That true?”

Flaherty shrugged. “I never saw her. Not when I locked up.”

“What about her car?”

“Her car,” he repeated dully. “Her car. I had it towed.”

“At night?”

“That morning,” he said. “When it became clear she skipped out on me.”

“Towed where?” I asked.

“My place,” he said. “For parts.”

And those parts had probably already been taken, along with anything incriminating. I didn’t say that aloud, though.

“You have any idea who killed her?” I asked.

“What do you care?” he asked, gaze suddenly back on me, and sharper than I would have expected.

I thought of Jed then, Jed as I’d seen him that day, staring at me, that flat look on his face. “If Jed killed her—”

“I didn’t see Jed touch nobody,” Flaherty said. “And I wouldn’t say if I did.”

I froze. “Why not?”

Flaherty frowned, his eyes small and bloodshot. “He’s the best mechanic I got.”

“But if he killed someone—”

“He didn’t kill no one.”

“How can you be so sure?”

“What happened, happened,” Flaherty said. “Let’s not go wrecking more lives.” Then he grabbed the bottle of beer he’d been nursing, and took a sip, his crippled hand looking unbalanced in the grimy afternoon light.

* * *

By the time I got back with the sheriff, Jed was gone. Not that it mattered. The case went down on the books as unsolved. What else could it have been with the other kid denying he’d even talked to me, and Mac Flaherty swearing that the girl’d been fine when he drove by at midnight, fine and unwilling to leave her post near the Coke machine. He’d winked at the sheriff when he’d told that story, and the sheriff seemed to accept it all.

I went to Jed’s apartment, and found the door open, all his clothes missing, and a neighbor who said that Jed had run in, not even bothering to change, and packed a bag, took some money from a jam jar he’d had under his bed, and disappeared down the highway, never to be seen again.

He’d been driving one of Flaherty’s rebuilds.

When I found out, I told the sheriff, and the sheriff’d been unimpressed. “Man can leave town if’n he wants,” the sheriff said. “Don’t mean he killed nobody.”

No, I suppose it didn’t. But it seemed like a huge coincidence to me, the girl getting beaten to death, Jed watching us talk, and then, when he knew I’d left for the law, disappearing like he did.

It was just the sheriff saw no percentage in pursing the case. It’d been interesting when he could come after me because of my family, because of the power we had, but it soon lost its appeal when the girl’s family took her away. Took her away, and pointed the finger at a good local boy, a mechanic who could down some beers and tell great jokes, who’d gone off to serve his country same as the rest of us. Jed had had worth to the sheriff; the girl had had none.

* * *

I don’t know why he killed her. We’ll never know now. Jed disappeared but good, and wasn’t heard from until five years ago, when what was left of his family got an obituary mailed to them from somewhere in Canada. He’d died not saying a word—

* * *

Sorry. Got interrupted there. Was going to come back to it this afternoon, but things changed this morning.

About nine a.m., I walked into my front room, buttoning one of my best shirts in preparation for yet another meeting with that pretty doctor down at the glass-and-chrome White Elephant, when I saw Sarah sitting in my best chair, feet on the footstool my granny hand-stitched, and all forty hand-written pages of this memory in her hands. She was reading raptly which I found flattering for the half second it took to realize what she was doing. I didn’t want any one to read this stuff until I was dead, and here was my granddaughter staring at the pages as if they were something outta Stephen King.

She looked up at me, her heart-shaped face so like Sally Anne’s at that age that it made my breath catch, and said, “So you think you’re some bad guy for failing this woman.”

I shook my head, but the movement didn’t stop her.

“You,” she says, “who’ve done more for people—black, white or purple—than anyone else in this town. You, who went and opened that civil rights law practice back east, who fought every racist law and every racist politician you could find. For godssake, Gramps, you marched with Dr. King, and you were a presidential advisor on Civil Rights. You’re the kinda man who shows the rest of us how to live our lives, and you’re feeling like this? You’re being silly.”

“You don’t understand,” I said.

“Damn straight,” she said, and I winced, as I always do, at the sailor language she uses. “You shouldn’t be mulling over this any more. You did what you could, and more, it seems, than anyone else.”

“And even that wasn’t enough.”

“Sometimes,” she said, “that happens, Gramps. You know that. Hell, you taught it to me.”

Seems I did. But that wasn’t the point either, and I didn’t know how to tell her. So I didn’t. I took the papers from her, put them back on my desk where they belonged, and let her drive me to the doctor so that they both could feel useful.

And all the way there and all the way back, I thought about how to make my point so that girls like her would understand. You see, the world is so different now, and yet it’s still the same. Just the faces change, and a few of the rules.

These days, Jed would’ve been arrested, or the sheriff would’ve been bounced out of office, or the press’d make some huge scandal over the whole thing.

But it wouldn’t be that simple, because pretty women don’t approach strange men any more, especially if the strange men are in uniform, and pretty women certainly don’t wait alone in gas stations while their cars are being repaired.

But they’re still dying, because they’re women or because they’re black or because they’re in the wrong place at the wrong time, and there’s so damn many of them we just shrug and move on, shaking our heads as we go.

But that isn’t my point. My point is this:

I wouldn’t have marched with Dr. King if it weren’t for that poor girl, and I wouldn’t have made it my life’s work to stamp out all the things that cause the condition I found myself in that hot afternoon, the condition that would have led me to ignore a girl if I’d noticed the true color of her skin.

Because I think I know why she died that day. I think she died because she’d flirted with me.

And that just wasn’t done between girls like her and men like me.

Jed wouldn’t have taken her to the desert if she were white. He would’ve thought she had family, she had someone who missed her. He might have roughed her up for talking to me. He might have had a few words with me.

But he didn’t. I did something unspeakable to people of our generation, and he saw a way to get back at me. If I’d talked to her, then I’d want to do what was probably done to her before she died. And if she’d fought, then I’d have bashed her. That’s what the sheriff was thinking. That’s what Jed wanted him to think.

And all because of who she was, and who I was, and who Jed was.

The sad irony is that if I’d kept my place, she’d be alive, and because I didn’t, she was dead. That had bothered me then, and bothers me now. Seems a man—any man—should be able to talk to whomever he wants. But what bothered me worse was the fact that when I learned, on the same morning, that she was black and that she was dead, it bothered me more that she was black and that I had talked to her.

It just wasn’t done.

And I was more worried about my own blindness than I was about one woman’s life.

Since that day, hers is the face I see every morning when I wake up, and every night when I doze. And, if God gave me the chance to relive any day in my life, it’d be that one, not, strangely, the day I enlisted or the day I deliberately misunderstood that German kid asking for clemency, but the day I inadvertently led a pretty girl to her death.

White liberal guilt maybe.

Or maybe it was the last straw, somehow.

Or maybe it was the fact that I had so much trouble learning her name.

Learning her name was harder than learning the identity of the man who killed her. It took me three more weeks and a bribe to the twelve-year-old son of the owner of the funeral home.

Not that her name really mattered. To me or to anyone else.

But it mattered to her, and to that man in uniform with the red, red eyes. Because it was the only bit of her that couldn’t be sold for parts. The only bit she could call completely hers.

Lucille Johnson.

Not quite as exotic as I would have thought, or as fitting to a woman as beautiful as she was. But it was hers. And in the end, it was all she had.

It was a detail.

An important detail.

And one I’ll never forget.

___________________________________________

“Details“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Details

Copyright © 2018 by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

First published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, December 1998

Published by WMG Publishing

Cover and Layout copyright © 2018 by WMG Publishing

Cover design by WMG Publishing

Cover art copyright © Amuzica/Dreamstime

This book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. All rights reserved. This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

The Inheritance: Chapter 4 Part 2

We are back from vacation! Clearly, a thousand ships have been launched while we were gone.

Before we delve: if you would like to reread The Inheritance from the beginning, uninterrupted, click The Inheritance tag under the post title. We now have a front page banner, and we would like to introduce Candice Slater, the talented artist who will be illustrating chapters for us. You can find her Instagram account here.

Artwork by Candice Slater

Artwork by Candice Slater

The cave passage stretched in front of me, a narrow tunnel painted with bioluminescent swirls of strange vegetation with a stream trickling along the left wall. The passage split about thirty yards ahead, with one branch curving to the right and the other cutting straight into the gloom.

I had a light on my hard hat but decided against using it. It didn’t illuminate much, while making me easy to target, and I had no idea how long the battery would last. It was better to save it for emergencies. The pale green and pink radiance of the foreign fungi and lichens offered some light but it made the darkness seem even deeper.

It was like I’d turned five years old again, lying in my bed in the middle of the night, too afraid to move, until the need to pee won out and forced me to make a mad dash to the bathroom. Except that back then, if I got really scared, I could flick the lights on. As long as you had electric light, it gave you an illusion of safety and control. Without it, I felt naked. It was just me, Bear, and the tunnels filled with underground dusk.

There would be no dashing here. We would go carefully, quietly, and slowly.

A cold draft flowed from the tunnel, bringing with it an odd acrid stench.

Bear whined softly by my side.

Whining seemed entirely appropriate. I didn’t want to go into that gloom either.

“We don’t have a choice,” I told the dog.

Something rustled in the darkness, a strange whispering sound.

Bear hid behind me.

“Some attack dog you are.”

That’s probably why she survived. If she were braver, she’d be dead.

“The exit is to our left. This is the closest tunnel to it. The other two branch off to the right, which will take us further from the gate. This is our best bet for getting out.”

Bear put her ears back.

“It will be okay. Well, no, it probably won’t be, but staying here isn’t an option. Come on, Bear.”

I started forward and tugged on the leash. She resisted a little, but then changed her mind, and followed me through the passage. We picked our way through the glowing growth. It looked almost like a coral reef that had somehow sprouted on dry ground.

We reached the fork. The stream flowed from the right branch, with a scattering of luminous plants along its banks. It promised light, but the banks were narrow and strewn with rocks and water would attract predators. We needed to hang left anyway, so I took the other path, straight into the gloom, and kept moving. The tunnel was about thirty feet high and probably the same width. An almost round a hole in the rock, as if some massive worm had burrowed through the mountain. Hopefully not.

The passage veered slightly left, then angled right. Normally, cave passages like this varied in size and shape. This one was too uniform. Whatever dug it out had to be huge.

Time stretched. We trudged forward, following the curves of the passageway. Occasionally Bear paused, listening to something I couldn’t hear. I let her take her time.

Back by the entrance, we’d passed by some stalker bodies, and Elena mentioned that the assault team didn’t wipe them all out. Taking on a single stalker would be difficult. There had been eight corpses, and the stalkers typically traveled in groups. If a pack of them attacked us, the best strategy would be to run and hope the tunnel narrowed ahead so they could only come at me one at a time. If I saw a crevasse, I would have to make a note of it in case I needed to double back…

For some reason, I could actually see both sides of the tunnel now with a lot of clarity. My eyes should have adjusted to the darkness, that was to be expected, but I could pick out small details now, like the cracks in the stone. The walls weren’t glowing, and the shining growth in this area was kind of sparse. Hmm.

We rounded another gentle turn, and I stopped. Ahead ridges of growth sheathed the floor and walls of the tunnel, like someone had raked solid stone into shallow curving rows. Between them bright red plants thrust out, shaped a little like branching cacti or Sinularia corals, almost like alien hands with long twisted fingers decorated with narrow frills. The tallest of them was about two feet high, but most were around eight inches or so. There were hundreds of them in the tunnel. The red patch stretched into the distance. Forty yards? Fifty?

Something about the red plants gave me pause. I crouched by the nearest patch. The frilly protrusions weren’t leaves. They were thorns, flat and razor sharp.

I flexed, accessing my talent. The red patch snapped into crystal clarity, flaring with a bright purple. Not helpful. Red was usually valuable, blue was toxic, orange was dangerous, but purple could be whatever.

I focused, trying to dig deeper.

The Grasping Hand. The thorns carried lethal poison. If one of those cut me or Bear, we would die in seconds, and the Hand would devour our bodies. In the distance, I could see a lump that was once a living creature, soon to become one of those ridges, drained of all fluids.

How did I know that? This hadn’t been in any of the briefings. I had never seen this before. I hadn’t read about it, no one had talked about it, and I should not have detailed knowledge of this carnivorous invertebrate. I shouldn’t have even known it was an invertebrate. The best my talent could do was identify it as animal and possibly dangerous.

The knowledge was just in my head. I flexed again, concentrating on the bright red stems.

A dark plateau unrolled in front of me, acres and acres of red stems, some twenty-feet-high, blanketing purple rock with giant dinosaur like reptiles thrusting through the growth, the stinging thorns sliding harmlessly from their bony carapace…

This was not my memory.

Fear washed over me. My heart pounded in my chest. I went hot, then cold. What the hell was happening to me?

Bear nudged me with her cold nose. I petted her, running my hand over her fur, trying to slow my breathing. Was this my inheritance? Memories from I didn’t know who obtained I had no idea where.

I stared at the patch. I could have a nervous breakdown right here and now, or I could keep going.

It didn’t matter where the damned memory came from. It warned me about the danger. It might not have been mine, but I knew it was true. Blundering into that growth was certain death.

The Grasping Hand grew in clusters, probably determined by the availability of nutrients. Each of those clumps or ridges used to be a body. This growth was relatively young, the stems short and somewhat sparse.

If I was careful, I could pick my way through it. The problem was Bear. There was no way to communicate to the dog that she had to stay away from the thorns. One tiny scratch and it would be all over. I had to keep Bear safe. No matter what it took. I owed it to Stella, and if Bear died… Bear couldn’t die. We would leave this place together.

I could carry her. She was a big dog, she had to weigh… I flexed again. Eighty-two pounds. And that was a lot more precise than normal. I could usually ballpark weight and distance but not with that much accuracy. Something told me that if I concentrated, I could probably narrow it down to ounces. Fuck me.

I focused on the field of red. Forty-eight yards or one hundred and forty-four feet.

Great. All I had to do was pick up an eighty-pound dog and carry her across half the length of a football field. While carefully avoiding deadly thorns.

I could always double back and try one of the other tunnels. But none of the other passages led toward the exit. We’d been walking for what felt like hours. It would be a long trip back, and there was no guarantee we wouldn’t run across this same problem in another tunnel.

Also, very few things could get through the Grasping Hand without some kind of body armor. It was a deterrent, a little bit of safety behind us. Nothing would come at us through that patch.

If I put Bear on my shoulders, I could make it. But not while I carried the backpack. The canteens were bulky and heavy, and the backpack pulled on me. If Bear squirmed, she would throw me off balance and both of us would land right into the thorns. It was the pack or the dog.

All of the water and food we had was in that pack. I could try to throw it ahead of me, but there was no telling where it would land or how far. Dragging it behind me was out of the question. It could get stuck and pull me back, and the thorns would either shred it or deposit poison on it. I had no effective way to neutralize it.

If I got through, I could find a safe spot on the other side, tie Bear to something, and come back for the pack. Yes, that had to be it.

I dropped the pack, pulled a second canteen out, and hung it on my coveralls. I had to take only what I absolutely needed. The antibacterial gel, a couple of bandages, knife, a single candy bar, and Motrin went into my pockets. That was all that could fit.

God, I didn’t want to leave the pack behind, but Bear mattered more. It would be fine. I would come back for it.

I took off my hard hat, pulled one of the spare canteens out of the backpack, poured water into the hat, and offered it to Bear. She lapped at it. I drank what was left in the canteen and waited until the shepherd stopped drinking. I took the hat, tapped it on the ground to get the last of the liquid out, and put it back on my head. It was the only helmet I had.

There was a command guild dogs were taught to make them easy to carry. I’d heard the handlers use it before. What the hell was it? Lie, rest… Limp. Limp, it was limp.

I tore the packet of jerky open, pulled a piece out, and offered it to Bear. She sniffed it and gently took it out of my hand.

“Good girl. See? We’re friends.”

I took another piece of jerky and crouched by the shepherd. “Limp, Bear.”

She stared at me.

“Limp.”

Another puzzled look.