Authors

Monday Meows

Oh, hell, is it Monday again? I’ve got nothing.

Gzzznorkzzzzzzzzz

I vote we bag it for the week.

I have a tail!

Announcing the sequel to HELL FOR HIRE...

HELL OF A WITCH

coming out Oct 1, 2024!

The hotly anticipated sequel to HELL FOR HIRE...

The hotly anticipated sequel to HELL FOR HIRE...One month ago, Bex, the demon queen, and Adrian, witch of the Blackwood, pulled off the upset victory of the century. Now, they find themselves facing the question all unexpected champions must answer: what next? They declared war on Heaven, but how do you actually bring down a divinely powerful tyrant when your army’s still in the single digits and your magical fortress is an illegally modified Winnebago?

It seems like a hopeless situation. As always, though, Adrian Blackwood has a plan, and this time, he’s going big. He’s got an idea to take down the Seattle Anchor, the giant magical fortress that houses the Anchor Market and every other bit of critical infrastructure that connects Heaven to Earth.

How the Anchors work is a closely guarded secret, and getting to the good stuff will require going deep into the heart of Gilgamesh’s power. There’s a reason even the Queen of Wrath has never attacked one directly, but now that Adrian’s on her team, Bex thinks they can do it. She’s finally got the power she needs to actually move the needle on this war, and she’s going to hit that Anchor with all the fire she’s got.

But the enemies of Heaven aren’t the only ones making plans. After the fiery return of his most persistent annoyance, Gilgamesh has ordered his princes to take care of the demon queen problem personally. It’s time to roll out the big guns and show these rebels what divine wrath really means, starting with the Hell of a Witch who made it all possible.

Coming out October 1 in ebook, Kindle Unlimited, paperback, hardback, and an absolutely incredible audio edition!Preorder Now!Boston, what are you doing? Get out from in front of the title!

*Attempts to push familiar away with broom. Broom and cat team up. The author is forced to retreat.*

Ahem... It's sequel time! Y'all made HELL FOR HIRE one of my best new launches ever, and now the second book is almost here. HELL OF A WITCH has more of everything you love, and it's coming out all formats on October 1! Hooray!

Thank you all so much for making this series such a success. I'm so grateful you're enjoying the story, because I love these misfits to death. So much that I've already written book 3, which will be coming out in early 2025! So many books! It's the best of times.

I really hope you'll give HELL OF A WITCH a try, and if you haven't cracked into my Tear Down Heaven series yet, what are you waiting for? It's awesome! The audio book in particular is *chef's kiss*. One of the best things we've ever done. Highly recommended.

Again, thank you all so so much for being my readers and listeners. I hope you love this book as much as I do. It's just so much fun and I can't wait for you to get into it. This series is going to be a truly epic ride.

Thanks again for making my dreams come true! Yours always and forever,

Rachel AaronWitch Career Counselor Assistant to the Familiars

HELL OF A WITCH is the second book in the Tear Down Heaven series. If you're new, start from the beginning with HELL FOR HIRE. I promise you won't be sorry!

Tempus fuck it!

In a few short days, Prince of Thorns becomes a teenager and will be the same age as Jorg himself for the first few pages of the novel!

I never expected to be an author. I certainly never expected this guy to pay off my mortgage. And I absolutely didn't expect to still be signing copies of the book in my local Waterstones 13 years after it was published.

The shelf life of an author is typically one book. Fantasy authors more often get a trilogy, because that's how fantasy rolls. But yup, not many of us hang around for long, and the past 13 years are littered with the bright flashes of many fine writers who came along about the same time as me.

I've said - so often that I'm bored of hearing myself say it - that all forms of writing success require large doses of luck. Skill at writing and at story telling are what buys you the lottery ticket. After that you need the stars to align.

It's easy to focus on the hyper-rare examples where the celestial alignment has been of atonishing proportions, and to feel a measure of discontent. But I'm constantly aware that so many fine writers have failed to flourish where I've been fortunate enough to make a living for over a decade now.

So, in part this post is a big thankyou to all you readers who've made that possible.

It's scary to look back at my bibliography and think that (with the exception of the Impossible Times books) each of those novels represents a year of my life. I have grown significantly older doing this...

People often talk to me about pride and about legacy, as if these stories are somehow more of an achievement than the myriad things everyone else has spent the last 13+ years on. I don't subscribe to that point of view, at all. Almost every book is a line drawn in wet sand and if the wave that will wash them away hasn't arrived in 13 years, then it's certainly going to hit the beach at some point, and sooner than most folk think.

I'm pleased and grateful that I've been able to share these stories, but 'proud' isn't a word I'd use. It's ... complicated.

Anyway, enough navel gazing. Just as I had no idea what the 13 years after Prince of Thorns hitting the shelves would look like, I have no idea where we'll be when the book reaches 18 or 21. Will anyone remember Jorg on the 25th anniversary in 2036 ... who knows.

For now though, the ideas keep coming and the itch to write continues to require scratching. I've finished three books this year, and hopefully will have a 4th done by Christmas.

Thanks for reading!

Join my Patreon.Join my 3-emails-a-year newsletter. #Prizes #FreeContent

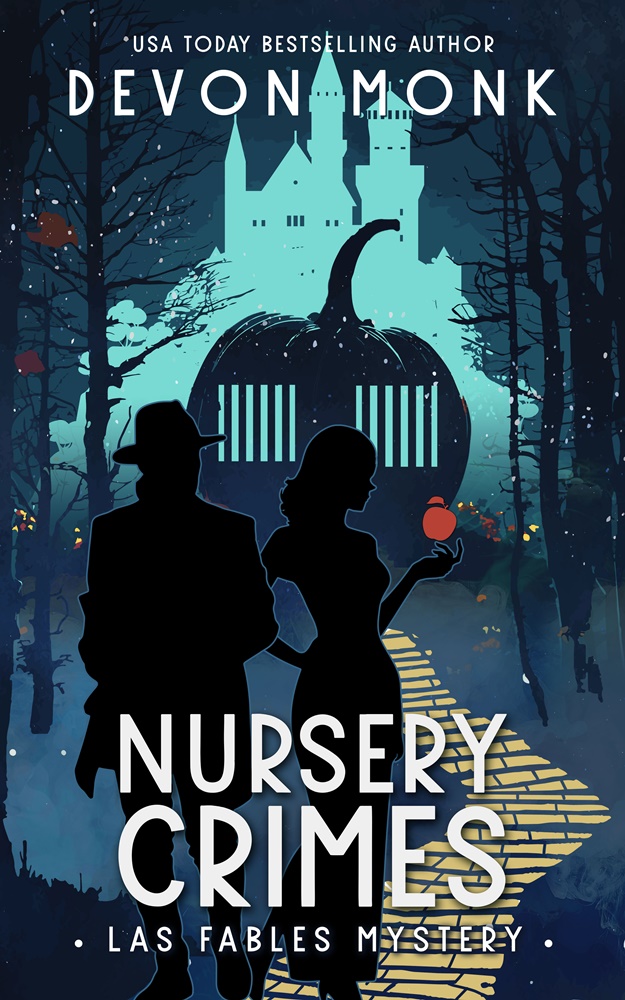

NURSERY CRIMES is Out Now!

This is the city of Las Fables. I work here. I’m Detective Peter Peter. I put ‘em in the pumpkin shell.

Las Fables is a land of fairy tales and rhymes. Sure, it used to be made of sugar and spice, but Mother Goose flew the coop and hasn’t been seen in years. Darkness has settled over the town, whiffling and galumphing down the yellow brick lanes.

When the Seven Dwarves are gunned down in the Old Woman’s Shoe Bar, Detective Peter Peter and his partner Jack Horner are on the case. No matter how over the hill and far away the clues take them, they’ll see that justice is served–not too hot, not too cold, but just right.

Of course it isn’t just crime on Peter Peter’s mind. There’s a dame named Muffet who’s got him in a tizzy. And it’s gonna take all of his willpower to keep his heart from tumbling down after her.

Amazon Apple Barnes and Noble KoboYes! Nursery Crimes is a short, fun standalone book set in the storybook land of Las Fables. I am so excited to finally get to share it with you! Just like the description says, it’s a smashup: hard-boiled mystery, fairy tales, nursery rhymes, and lots and lots of ridiculous jokes.

I hope you enjoy! (print will be available soon!)

HELL FOR HIRE is out today!

"Featuring a motley crew of loveable demons, a chaotic male forest witch with a sassy talking cat familiar, snarky sentient weapons, wicked warlocks, and plenty of magical mayhem, Hell for Hire is a bewitching and diabolically fun urban fantasy that is as thrilling as it is wholesome." - Before We Go Book Blog

"Featuring a motley crew of loveable demons, a chaotic male forest witch with a sassy talking cat familiar, snarky sentient weapons, wicked warlocks, and plenty of magical mayhem, Hell for Hire is a bewitching and diabolically fun urban fantasy that is as thrilling as it is wholesome." - Before We Go Book Blog"Rachel Aaron has never ever failed to deliver an effortlessly engaging story filled with lovable characters, and an amazing, yet accessible, worldbuilding that is uniquely hers. It came as no surprise that Hell For Hire has all her usual winning trademarks and is possibly her best first book in a series so far." - Novel Notions

"Hell for Hire is an urban fantasy tale that follows a ragtag group of demons and the outcast witch they're hired to protect. Boasting loveable characters, unique lore, and a whole lot of heart, this urban fantasy romp is an absolute delight." - Simple Reads

"Hell For Hire is an absolute blast to read as it combines action, comedy, and lots of magic for a unique story. Rachel Aaron with her eighth (or ninth) series opener showcases exactly why she has no peers in the urban fantasy genre. If you want to have lots of fun, thrills and action, look no further. Hell For Hire is available to fulfill all your needs and more." - Fantasy Book Critic

"Aaron has done it again, giving us a whole new world in which to enjoy her outstanding craft. While many of the themes will be familiar, Aaron has created something fun and wonderful that delighted me. I blazed through this book, sacrificing sleep and productivity. Loved the world building and as usual with Aaron, loved her characters and the obstacles they face, overcome, and the new crises that arise from the ashes to challenge the protagonists anew. Can’t wait for the next book! This is already a must-read." - J Graham (audiobook review)Get your copy now in ebook, print, audio, or KU!The time has finally come! I finally get to share the book that's consumed my last year with you, and I can't wait for you to read/listen to HELL FOR HIRE, which is available right now in ebook, print, audio, and Kindle Unlimited!

I know it's not the DFZ and there aren't any dragons (yet), but I still hope you'll give it a try, because this book was an absolute blast to write! I've never had so many great critic reviews right off the bat. And if you're worried about starting a new book 1, I've got you, because book 2 is already written and going through proofreads, which means it will be available later this year. This series, she is rolling!

And speaking of rolling, you should give the audio edition a try on this one, because our new narrator, Nicholas Cain, narrated the hell out of it, pun entirely intended. ;) The audiobook is also available in stores other than Audible this time! Here's a list of all places you can find it, I hope you'll give the story a listen :D

If print is more your thing, we have hardbacks, and they are sexy! I mean, just look at this.

Ah, the sight fills my book-hording heart with joy <3

I think that's enough promo for one morning. Thank you all so, so much for coming along with me on this crazy journey! I couldn't do any of this without your support, and I hope from the bottom of my heart that you love HELL FOR HIRE as much as I do. Thanks again, and I'll see you for the next book!

Yours sincerely,

Rachel AaronProfessional Familiar Consultant, talk to me about talking cats!

HELL FOR HIRE is the first book in the new Tear Down Heaven series, which will be five books in total. The second book will be out in Fall of 2024. I hope to see you then!

New series!!

Introducing...HELL FOR HIRE coming out June 4!

The Crew

The CrewA hulked-out wrath demon who eats gamer rage and loves cats, a shapeshifting lust demon who enjoys their food a bit too much, and a void demon who doesn’t see the point of any of this. They’re not the sort of mercenaries you hire on purpose, but Bex wouldn’t trust her life to anyone else.

Ever since the ancient Mesopotamian king Gilgamesh decided death wasn’t for him, killed the gods, and conquered the afterlife, times have been rough for a free demon. But the denizens of the Nine Hells aren’t the quitting sort, and Bex and her team have been choking a living out of the Eternal King’s lackeys for years. It’s not honest work, but when Heaven itself declares you a non-person, you smash-and-grab what you can get.

This next gig looks like more of the same…until Bex meets the client.

The Job

Adrian Blackwood is a witch with a problem. His family has skirted the edges of King Gilgamesh’s ire for centuries, but thanks to a decision he made as a child, Adrian is personally responsible for putting his entire coven in Heaven’s crosshairs.

Determined to set things right, Adrian drags his broom, caldron, and talking cat thousands of miles across the country to Seattle where he can fight the Eternal King’s warlocks without bringing the rest of his family into the fray. But witchcraft--like all crafts--takes time, and if the warlocks catch him before his spells are ready, he’s dead. So Adrian does what any professional witch would do and hires a team of mercenaries to keep the warlocks off his back. He didn’t expect to get demons, but when you’re already on the killing-edge of Heaven’s bad side, what’s a bit more fuel on the fire?

Sometimes you get more than you paid for.

Neither Adrian nor Bex knew what to expect when they signed their contract, but witch-plus-demon turns out to be a match made in the Hells. With this much chaos at their fingertips, even impossible dreams start to come back into reach, because Bex wasn’t always a mercenary. She used to be the Eternal King of Heaven’s biggest nightmare, and now that she’s got a witch in her corner, it’s time to put the old magics back on the field and show Adrian Blackwood just how much Hell he’s hired.

Preorder Now!Big day in book-land!

First up, BY A SILVER THREAD is on sale this week for $0.99, so if you haven't given my new DFZ Changeling series a try, now's a great time to pick it up for cheap!

Second (and way more excitingly), I've got a brand-new book for you to dive into! Introducing HELL FOR HIRE, the first in the Tear Down Heaven series and a return to the classic Rachel-Aaron-style of big ensemble casts full of funny characters, crazy magic, world-ending stakes, and epic swordfights. If you liked my Eli Monpress fantasy books or the original Heartstrikers series, this is going to be right up your alley. There's a new magical system, demons with weird immortality issues, witch-family drama, and terrifying heavenly princes who will murder you while looking gorgeous. It's just a ton of fun and I can't wait for you to read it!!

HELL FOR HIRE comes out June 4, 2024 in all formats, including ebook, print, KU, and audio. If any of that changes, I'll be sure to let you know. Thanks for being my readers/listeners! I couldn't do any of this without you.

Yours always,

Rachel AaronDivine Orchestrator Professional Demon Herder

Want to see all of my books in order, read samples, and know which series are finished? Visit www.rachelaaron.net!

Launch day! TO THE BLOODY END is out now in all formats!

No Victor lasts forever.

Victor thought he won when he became the Hero. He thought he won when he took over the DFZ. He thought he’d made himself untouchable.

He’s wrong.

Lola isn’t the sad little monster she used to be. She has a plan, she has allies, she has more magic than she ever dreamed possible. Killing one blood mage should be easy with an entire fairy kingdom at her fingertips, but Victor didn't make himself a god by playing fair, and his bag of tricks is far from empty. Taking him down will require everything Lola and her friends can bring, but if there’s one thing Lola’s always been, it’s determined. No matter the cost, no matter what it takes, she will see this through.

To the bloody end.

Get your copy now in ebook, KU, print, or audio!This was an extremely satisfying book to write. I don't think I've ever enjoyed wrapping a series so much. It's epic, it's awesome, and I cannot wait for you to read it in ebook, print, or KU or listen on audio, cause they're all out today!Thank you so much for coming with me on Lola's journey. This wasn't the sort of story I ever thought I'd write, but when the book needs to happen, it needs to happen, and I'm very glad this one did. I hope you enjoy this series as much as I do and that you'll join me for what comes next.

And speaking of what comes next...

This is going to be a very exciting year for new releases! Lola's series is done, but I've got a brand new Urban Fantasy set in a brand new world that I think you're really going to enjoy.

The first book will be called HELL FOR HIRE and it's all about a team of demon mercenaries who get hired by a witch. There's tons of action, mystery, ancient Sumerian sorcery, a loveable snarky cast, a know-it-all talking cat, magical sword fighting, and overall hijinks in modern Seattle. It's just the BEST. I'm so in love that I'm already working on the draft for book 3. It's THAT GOOD, and as soon as I have a cover, you will be seeing a lot more of my new favorite thing. This is the most fun I've had with a series since Heartstrikers, and I just know you're going to love it.

So yeah, gonna be a lot of reads coming in 2024. :) As always, mailing list gets first dibs on everything, so sign up if you're not already and keep an eye on your email box, 'cause it's going to get wild!

Thank you again so much for being my reader/listener. You are the reason these stories exist, and I hope you'll come along with me for many more novels to come. Thank you from the bottom of my heart, and please enjoy TO THE BLOODY END!

Yours always,

Rachel AaronMother of Dragons Bethesda's Unpaid Intern

TO THE BLOODY END is the third book in the DFZ Changeling trilogy. If you're new, start from the beginning with BY A SILVER THREAD. I promise you won't be sorry!

TO THE BLOODY END cover reveal!

No Victor lasts forever.

Victor thought he won when he became the Hero. He thought he won when he took over the DFZ. He thought he’d made himself untouchable.

He’s wrong.

Lola isn’t the sad little monster she used to be. She has a plan, she has allies, she has more magic than she ever dreamed possible. Killing one blood mage should be easy with a fairy kingdom at her fingertips, but Victor didn't make himself a god by playing fair, and his bag of tricks is far from empty. Taking him down will take everything Lola and her friends can bring, but if there’s one thing Lola’s always been, it’s determined. No matter the cost, no matter what it takes, she will see this through.

To the bloody end.

Preorder Now!Happy 2024 everyone!I've got a lot of good books lined up for y'all this year, but first... The end is nearly upon us! The third and final book in Lola's epic quest to punch Victor in the face comes out on February 2, 2024 in ebook, print, KU, and Audible audio book! Hooray!!

Mailing list subscribers have already seen this (not on the list yet? Sign up now! It's free, there's no spam, and you get first dibs on everything!) but here's the cover for TO THE BLOODY END featuring the art of the amazing Luisa Preissler! I love the torn up Hero poster behind her and the glowing crown on her head (which IS in the book, and it's GREAT!).

This series has been a wild ride and I'm so pumped for you to finally read the ending. It's one of the most exciting and strange final battles I've ever written. I think you're going to really like it, so if you haven't already, please preorder the book or add it to your KU to read list so you don't miss out!

This is hopefully just the first of many books I'll have for you this year. I don't want to overshadow Lola (poor little changeling has been through enough) but I've got a brand new Urban Fantasy in a brand new world involving witches launching this summer, and it is SO much fun! Mailing list people will be getting everything first, so sign up if you haven't yet, and I promise you'll hear all kinds of cool things from me soon!

Thank you again for being my fans. I couldn't do any of this without you!

Yours sincerely,

Rachel AaronMayor of the DFZ

TO THE BLOODY END is the third book in the DFZ Changeling series. If you're new, start from the beginning with BY A SILVER THREAD! I promise you won't be sorry!

WITH A GOLDEN SWORD is out now!

Standing up to Victor was only the beginning.

Three weeks ago, Lola put her soul on the line to save her sister and stop an abusive blood mage from making himself a god. But while she managed to derail the worst of Victor’s plans, the rest of the world still sees her old master as the hero. To make matters worse, the Nightmare King Alberich has entirely escaped his prison and is now leading the Wild Hunt on a rampage of fear and chaos across the skies of Europe.

With Alberich playing the villain, it’s only a matter of time before Victor convinces all of humanity that his abusive magic is their only hope. Lola’s not about to let him get his dirty hands on that kind of power. But while she’s free to fight him, Simon and the Black Rider are still trapped under the blood mage’s boot. Lola will have to break them both out before she can take Victor down, but her former master’s plans are far from finished. He’s playing a game none of them can predict for a prize no one yet understands, and once all of his pieces are in place, the future of the world will hang on the edge of a golden sword.Get Your Copy Now!Hooray! It's here! WITH A GOLDEN SWORD is out today in eBook, KU, print, and audio!

WITH A GOLDEN SWORD is the second in Lola's trilogy, but since I've been on a crazy writing binge, the third book, TO THE BLOODY END, is already written and up for preorder! This means the series will be complete Feb of next year, which I'm pretty sure is some kind of record for me o_o. I've just been on fire for this series and I can't wait for y'all to see where it goes.

Thank you all so much for coming on yet another DFZ journey with me! I hope you check out the book, have a great week, and I'll talk to you all again when the next book is on the horizon. Until then, please enjoy WITH A GOLDEN SWORD!

Yours always,

Rachel AaronCat Endangerer Loving Author

WITH A GOLDEN SWORD is the second book in the DFZ Changeling series. If this is the first you've heard about it, start from the beginning with BY A SILVER THREAD! I promise you won't be sorry!

BY A SILVER THREAD is out today!

"Exquisitely trademark Rachel Aaron. Immensely readable & instantly engaging, with new characters that you can't help loving. The inclusion of fairy lore just leveled up the already fascinating world of the DFZ. So good, so fun!"- TS Chan, Novel Notations

"Exquisitely trademark Rachel Aaron. Immensely readable & instantly engaging, with new characters that you can't help loving. The inclusion of fairy lore just leveled up the already fascinating world of the DFZ. So good, so fun!"- TS Chan, Novel NotationsIn the world’s most magical metropolis where spirits run noodle shops and cash-strapped dragons stage photo-ops for tourists, people still think fairies are nothing but stories, and that’s exactly how the fairies like it. It’s a lot easier to feast on humanity’s dreams when no one believes you exist. But while this arrangement works splendidly for most fair folk, Lola isn’t one of the lucky ones.

She’s a changeling, a fairy monster made just human enough to dupe unsuspecting parents while fairies steal their real child. The magic that sustains her was never meant to last past the initial theft, leaving Lola without a future. But thanks to Victor Conrath, a very powerful--and very illegal--blood mage, she was given the means to cheat death.

For a price.

Now the only changeling ever to make it to adulthood, Lola has served the blood mage faithfully, if reluctantly, for twenty years. Her unique ability to slip through wards and change her shape to look like anyone has helped make Victor a legend in the DFZ’s illegal-magic underground. It’s not a great life, but at least the work is stable… until her master vanishes without a trace.

With only a handful left of the pills that keep her human, Lola must find Victor before she turns back into the fairy monster she was always meant to be. But with a whole SWAT team of federal paladins hunting her as a blood-mage accomplice, an Urban Legend on a silent black motorcycle who won’t leave her alone, and a mysterious fairy king with the power to make the entire city dream, Lola’s chances of getting out of this alive are as slender as a silver thread.Get your copy now!The wait is finally over! BY A SILVER THREAD comes out today in ebook, KU, and print!

Hold up, Rachel, where is the audio book?I'm asking the same question. It was supposed to come out today, but it's trapped in Audible's review process and no one will tell me why. I'm working on the problem right now and I promise I will send another email as soon as it's available, which will hopefully be very very soon. Come on, Audible, get it together!

For all of you who read books with your eyes, the ebook and print editions are out and ready to enjoy. If you preordered a copy, thank you! The book should already be on your Kindle. If you prefer KU, you're also ready to go! Head on over and click the button to start enjoying the story. I hope you love it as much as I do!

But wait, there's more!As I mentioned in the last email, I've been on fire for this story, and the fire has paid off. No more waiting forever for a sequel. The next book in the DFZ Changeling series, WITH A GOLDEN SWORD, is already written and will be out on October 2!

Why the long wait if it's already done? Well, as you'll see, the book has no cover yet or anything else. Writing is only the first step in a long process of making a quality book. But the novel is finished AND there's a sneak preview of the first chapter in the back of book 1! So if you love BY A SILVER THREAD, which I very much hope you will, rest assured that the rest of the series will be coming out swiftly.

Can I read this book if I haven't read any of the other DFZ stories?Yes! Just like MINIMUM WAGE MAGIC, I wrote BY A SILVER THREAD to be an entry point for new readers. You don't need to know anything about the DFZ to enjoy it, but if you are a fan of my other series, I packed in a lot of goodies for you to enjoy. It's a win/win for everybody!

As always, thank you so so much for being my readers and listeners. I hope you love BY A SILVER THREAD as much as I do!

Yours always,

Rachel AaronChronic Magical City Endangerer

Ready for a new DFZ novel?

Return to the DFZ with a brand new series, introducingBy A Silver Thread

In the world’s most magical metropolis where spirits run noodle shops and cash-strapped dragons stage photo-ops for tourists, people still think fairies are nothing but stories, and that’s exactly how the fairies like it. It’s a lot easier to feast on humanity’s dreams when no one believes you exist. But while this arrangement works splendidly for most fair folk, Lola isn’t one of the lucky ones.

In the world’s most magical metropolis where spirits run noodle shops and cash-strapped dragons stage photo-ops for tourists, people still think fairies are nothing but stories, and that’s exactly how the fairies like it. It’s a lot easier to feast on humanity’s dreams when no one believes you exist. But while this arrangement works splendidly for most fair folk, Lola isn’t one of the lucky ones.She’s a changeling, a fairy monster made just human enough to dupe unsuspecting parents while fairies steal their real child. The magic that sustains her was never meant to last past the initial theft, leaving Lola without a future. But thanks to Victor Conrath, a very powerful--and very illegal--blood mage, she was given the means to cheat death.

For a price.

Now the only changeling ever to make it to adulthood, Lola has served the blood mage faithfully, if reluctantly, for twenty years. Her unique ability to slip through wards and change her shape to look like anyone has helped make Victor a legend in the DFZ’s illegal-magic underground. It’s not a great life, but at least the work is stable… until her master vanishes without a trace.

With only a handful left of the pills that keep her human, Lola must find Victor before she turns back into the fairy monster she was always meant to be. But with a whole SWAT team of federal paladins hunting her as a blood-mage accomplice, an Urban Legend on a silent black motorcycle who won’t leave her alone, and a mysterious fairy king with the power to make the entire city dream, Lola’s chances of getting out of this alive are as slender as a silver thread.By A Silver Thread is the first in a new, stand-alone DFZ series set right after the end of Opal's series. There are cameos from old favorites and a brand new cast of charming, sinister fairies you'll love to hate.

Coming out May 2, 2023!Preorder Now!What is this? A new DFZ novel so soon?

Yes, we are back in everyone's favorite city with a brand-new cast and a whole host of horrifying new problems. It was not my intention to start a new series until the Mary Good Crow books were done, but this idea would not let me go, so here we are.

I am so, so excited for y'all to read this book! It's got everything we love about the DFZ, but from an entirely new angle. It's action packed, and I think the magic is some of the coolest I've ever written. I had an absolute blast writing this book... and the sequel, which is already with the editor. What, I told you I was on fire! I just couldn't stop writing, and now you get more books. It's a win-win!

So does this mean the Western books are on hold? Absolutely not. I'm writing the third Mary novel as we speak. So yes, I am writing two series at once, but given how crazy I've been for these books, it definitely won't be long before they're all in your hands. I've already got two more launches lined up for this years, and next year should be at least two. It feels so good to be writing again after the Covid downturn. I can't wait to share everything I've been working on with you!

By A Silver Thread will launch in all formats (print, audio, ebook, and KU) on May 2. You can preorder the ebook now or wait until launch day for all the formats. Just don't forget to order, because you're going to want to read this book. Thank you so much for being my readers. I can't wait to see how much you'll love Lola's story!

Yours with extreme enthusiasm,

Rachel AaronMother of Dragons Bethesda's Unpaid Intern

Interview time!

Happy launch day to THE BATTLE OF MEDICINE ROCKS!

Today's the day!

When Mary Good Crow came out of the crystal into the arms of her sister, the last thing she wanted was another fight. But war is coming to the Great Plains. With crystal on their side, the Lakota are poised to annihilate the town of Medicine Rocks, forcing Mary to choose between the friends she’s finally found and the family she’s always longed for.

When Rel Reiner accepted her father’s dark bargain to save Josie and the others, the last thing she expected was to survive. But there’s more to the Reiner’s magic than ghosts and bones. Magic Rel will have to embrace if she ever wants to walk in her own skin again.

When Josie Price left the crystal mines one step ahead of death, the last thing she intended to do was quit. But the wolves in town are circling, and with the crystal going crazy and the cavalry riding to war, just finding a way to protect her people might cost her everything she came to Montana to build.

Three women divided by a war none of them wants. But Josie, Mary, and Rel have always been strongest together, and with the world’s magical future on the line, “together” might be the only way anyone survives.

Get your copy now in ebook, audio, print, or KU!

I can’t tell you how excited I am for y'all to read this book! I'm sooo proud of this ending and this series as a whole. If you haven't tried out THE LAST STAND OF MARY GOOD CROW yet, I hope you'll give it a go! This series has been such a wild ride, and I really hope you enjoy it!

This is the first launch for what I hope is going to be a very busy 2023. I’ve got a new DFZ series I’ll be announcing soon along with other fun stuff, so if you're not already subscribed to my New Release Newsletter, I hope you'll come over and say hi! Subscribers always get first dibs on the good stuff, I never share your info, and I only send out emails when I have a new book. No risk, just awesome, so I hope you'll join in!

Thank you so much for all your support over the years. Enjoy THE BATTLE OF MEDICINE ROCKS, and I’ll see you soon with a new story!

Yours with a hat tip,

Rachel Aaron

The next Mary Good Crow book comes out Feb 1!

When Mary Good Crow came out of the crystal into the arms of her sister, the last thing she wanted was another fight. But war is coming to the Great Plains. With crystal on their side, the Lakota are poised to annihilate the town of Medicine Rocks, forcing Mary to choose between the friends she’s found and the family she’s always longed for.

When Rel Reiner accepted her father’s dark bargain to save Josie and the others, the last thing she expected was to survive. But there’s more to the Reiner family’s magic than ghosts and bones. Magic Rel will have to embrace if she ever wants to walk in her own skin again.

When Josie Price left the crystal mines one step ahead of death, the last thing she intended was to quit. But the wolves in town are circling, and with the crystal going crazy and the cavalry riding to war, just finding a way to keep going might cost her everything she came to Montana to build.

Three women divided by a war none of them wants. But Josie, Mary, and Rel have always been strongest together, and with the entire world’s magical future on the line, “together” might be the only way anyone survives.

The second book in The Crystal Calamity, coming out February 1!

Preorder Now!What's better for the new year than a new book? How about several new books?

I've been writing like crazy and should have a lot of new titles coming for you all this year, but this first one is a doozy. THE BATTLE OF MEDICINE ROCKS is the sequel to THE LAST STAND OF MARY GOOD CROW and has (I think) the best ending I've ever written. I'm super proud of how it came out and cannot wait for y'all to read it on February 1!

Even better, we've finally managed to line up all formats to release simultaneously! Whether you prefer ebook, print, or audio book, they all release on the same day. It's everything, everywhere, all at once, and really pretty to boot! Seriously, the print version is gorgeous.

Whatever format you fancy, I really, really hope you enjoy this new entry in the Crystal Calamity. I know Western fiction isn't everyone's thing, but if you haven't given book 1 a try yet, I hope you'll give me a shot. And for those of you already in the know, I can't wait for you to read what comes next. It's gonna be a blast!

Thank you as always for being my readers and listeners, and I hope you enjoy THE BATTLE OF MEDICINE ROCKS!

Yours with a respectful hat tip,

Rachel Aaron

The Last Stand of Mary Good Crow is now out in Audio!

"Brimming with imagination, wonderful characters and captivating magic. "

- Novel NotionsThe long awaited day is finally here! The fantastic audio book of my newest novel, THE LAST STAND OF MARY GOOD CROW, officially goes on sale today!

If you already own the ebook, you can pick up the audio edition for super cheap! Who said audio books had to be expensive? I get paid the same either way, so there's no reason not to get yourself a deal!

I think Naomi Rose-Mock did a fantastic job with all the characters. I really hope you'll give it a try. Thank you as always for being my readers (and listeners!), and I hope you'll enjoy the audio edition of The Last Stand of Mary Good Crow!

Yours always,

Rachel

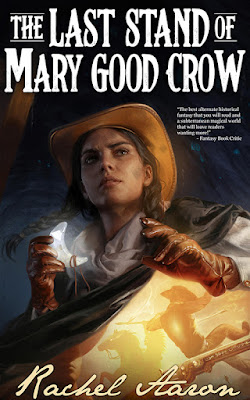

THE LAST STAND OF MARY GOOD CROW comes out today!

It's time!

Hungry darkness, haunted guns, tunnels that move like snakes--the crystal mines of Medicine Rocks, Montana are a place only the bravest and greediest dare. Discovered in 1866, the miraculous rock known as crystal quickly rose to become the most expensive substance on the planet, driving thousands to break the treaties and invade the sacred buffalo lands of the Sioux for a chance at the wealth beneath. But mining crystal risks more than an arrow in the chest. The beautiful rock has a voice of its own. A voice that twists minds and calls unnatural powers.

A voice that turns men into monsters.

Mary Good Crow hears it. Half white, half Lakota, rejected by both, she’s forged a new life guiding would-be miners through the treacherous caves. To her ears, the crystal sings a beautiful song, one the men she guides would gladly burn her as a witch for hearing. So, when an heiress from Boston arrives with a proposition that could change her life, Mary agrees to push deeper into the caves than she’s ever dared.

But there are secrets buried in the Deep Caves that even Mary doesn’t know. The farther she goes, the closer she gets to the voice that’s been calling her all this time. A voice that could change the bloody story of the West, or destroy it all.

"Possibly the best alternate historical fantasy that you will read."- Fantasy Book Critic

It's finally here! The first book in my new series is out today in ebook, print, and Kindle Unlimited! HOORAY!

We're recording the audio version right now, so hopefully that will be available quickly as well. I'll send an email as soon as I have a date, so make sure you're subscribed to my New Release Mailing List to get all the info on, well, new releases! (And nothing else. Trust me, I hate spam as much as you!)

Thank you all so much for being my readers, and I hope you love Mary's story!

Yours always,

Rachel Aaron

FINALLY! A new novel! Introducing THE LAST STAND OF MARY GOOD CROW

It’s been a while, but I’m back with an new novel in an new world! Get ready for…

Deadwood meets Lord of the Rings in this Epic Fantasy of the West!

Hungry darkness, haunted guns, tunnels that move like snakes--the crystal mines of Medicine Rocks, Montana are a place only the bravest and greediest dare. Discovered in 1866, the miraculous rock known as crystal quickly rose to become the most expensive substance on the planet, driving thousands to break the treaties and invade the sacred buffalo lands of the Sioux for a chance at the wealth beneath. But mining crystal risks more than an arrow in the chest. The beautiful rock has a voice of its own. A voice that twists minds and calls unnatural powers.

A voice that turns men into monsters.

Mary Good Crow hears it. Half white, half Lakota, rejected by both, she’s forged a new life guiding would-be miners through the treacherous caves. To her ears, the crystal sings a beautiful song, one the men she guides would gladly burn her as a witch for hearing. So, when an heiress from Boston arrives with a proposition that could change her life, Mary agrees to push deeper into the caves than she’s ever dared.

But there are secrets buried in the Deep Caves that even Mary doesn’t know. The farther she goes, the closer she gets to the voice that’s been calling her all this time. A voice that could change the bloody story of the West, or destroy it all.

Coming to eBook and Kindle Unlimited on JUNE 1, 2022! Print and Audio release coming soon!

Hello everyone!

I know it’s been a while since we left Opal in the DFZ. Like everyone else on the planet, I got kicked down pretty hard by the pandemic. But sometimes being forced to step away from your work means space gets made for something different, and wow, is this different.

THE LAST STAND OF MARY GOOD CROW is a story I’ve been wanting to tell for a long time. We’re talking crazy magic, giant battles, haunted guns, messed up family situations, sky-high stakes, and (of course) a giant cast of fun, hot-mess characters all set against the epic backdrop of the Great Sioux War, which ends veeeeery differently than the real one. (Don’t worry, Custer still dies.)

I realize historical Western feels like a pretty big jump from Urban Fantasy, but this is a Rachel Aaron book through and through. If you liked my other series, I heartily encourage you to give this one a try. I promise you won’t be disappointed!

You can read a sample right now over on my website. The eBook and Kindle versions will be out on June 1, 2022 with print very soon after. For those who prefer audio books, we’re recording right now, so it won’t be too long of a wait. I’ll send another email to let you know as soon as the audio version is available.

Thank you as always for being my readers/listeners! Y’all are the ones I write for, and I just can’t wait for you to start THE LAST STAND OF MARY GOOD CROW!

Yours always,

Rachel Aaron

NIGHT SHIFT DRAGONS comes out today in ebook and audio!

They say family always sticks together, but when you’re your dad’s only lifeline and the whole world—humans, dragons, and gods—wants you dead, “family bonding” takes on a whole new meaning.

My name is Opal Yong-ae, and I’m in way over my head. I thought getting rid of my dad’s bad luck curse would put things back to normal. Instead, I’m stuck playing caretaker to the Great Dragon of Korea. That wouldn’t be so bad if he wasn’t such a jerk, or if every dragon on the planet wasn’t out to kill him, or if he were my only problem.

Turns out, things can always get worse in the DFZ. When a rival spirit attacks my god/boss to turn the famously safety-optional city into a literal death arena with Nik as his bloody champion, I’m thrust onto the front lines and way out of my comfort zone. When gods fight, mortals don’t usually survive, but I’m not alone this time. Even proud old dragons can learn new tricks, and with everything I love falling to pieces, the father I’ve always run from might just be the only force in the universe stubborn enough to pull us back together.

Get your copy now!

They say family always sticks together, but when you’re your dad’s only lifeline and the whole world—humans, dragons, and gods—wants you dead, “family bonding” takes on a whole new meaning.

My name is Opal Yong-ae, and I’m in way over my head. I thought getting rid of my dad’s bad luck curse would put things back to normal. Instead, I’m stuck playing caretaker to the Great Dragon of Korea. That wouldn’t be so bad if he wasn’t such a jerk, or if every dragon on the planet wasn’t out to kill him, or if he were my only problem.

Turns out, things can always get worse in the DFZ. When a rival spirit attacks my god/boss to turn the famously safety-optional city into a literal death arena with Nik as his bloody champion, I’m thrust onto the front lines and way out of my comfort zone. When gods fight, mortals don’t usually survive, but I’m not alone this time. Even proud old dragons can learn new tricks, and with everything I love falling to pieces, the father I’ve always run from might just be the only force in the universe stubborn enough to pull us back together.

Get your copy now!

And thus Opal's journey comes to its grand conclusion! The final book in the DFZ trilogy, NIGHT SHIFT DRAGONS, is out today in audio and ebook! Some of you have already gotten your copies and binged, and I can't thank you enough!

I hope you all love this story as much as I loved writing it. Opal has been one of the most fun characters ever to write, even if she did leave me craving pancakes. Thank you for going on this journey with me! You are the best readers a writer could have!

For those wondering what's next, I'm working on a brand new series in a brand new world! You'll all get the details as soon as I'm sure the project will actually fly, but please know this is NOT my last book in the DFZ. I've already got a great idea for another book, so don't worry. We're not done with the dragons yet!

Again, thank you so so much for being my fans. Your enthusiasm and enjoyment is why I do this. Enjoy the book, and I'll be back soon with more!

Yours always,

Rachel Aaron Mother of Dragons Bethesda's Unpaid Intern

NIGHT SHIFT DRAGONS is the third book in the DFZ series. If you're new, start from the beginning with MINIMUM WAGE MAGIC! I promise you won't be sorry!

Mining Our Characters’ Wounds

While we can certainly be forgiven for not seeing our personal wounds as jewels, our most powerful wounds often have as many facets and hidden depths as an exquisitely cut gemstone. They are sharp, with hard edges that not only reflect back light but distort it somewhat.

As writers, we know that our character’s wounds are some of the most fertile ground for creating a rich, fully realized protagonist. But before we can explore this with our characters, we have to understand it ourselves. And because we have all been wounded in some way—and those places are always tender—it can be uncomfortable to look too closely.

In order to use our characters’ wounds to full effect, we need to understand that wounds aren’t simply an attribute to be filled in on a worksheet. They are the rocket fuel for our character’s backstory, the backstory that drives their motivation and colors their world. It must be deeply organic to that character and so intricately woven into their emotional DNA that it distorts the way the see the world and themselves.

While everyone’s wounds are uniquely theirs, they are also universal in that they’re something we all share. What differs is their nature, how we carry them, and the many—often unexpected—ways they shape us and our behavior.

Because of course the impact of any given wound isn’t limited to that initial injury. I was reminded of that last week when I was out walking and twisted my ankle. It was nothing serious, but by the time I’d limped around favoring it for a day or two, everything else was out of whack as I contorted my body to accommodate the injury.

Emotional wounds are just like that, only worse by orders of magnitude.

Even when we know our character’s painful past, we often don’t use it to full effect. We don’t manage to weave into the very essence of who our character is—because make no mistake, wounds fundamentally shape us, especially those incurred in childhood when we are so defenseless. With wounds of the heart or soul—the ones that violate some deep fundamental part—it is the repercussions of that initial wound that create the most scarring. The blame, the self-doubt, the suffocating shame, all serve as a way to cut us off from our core self.

Emotional neglect, a betrayal, a rejection, a lie, are all painful enough, but often become the lens through which we see ourselves. We accept that rejection. Believe that lie. Justify the betrayal due to something fundamentally flawed within us rather than the betrayer. Or worse, we don’t see it as a betrayal at all, but simple evidence of how flawed and unlovable we really are.

The emotionally abandoned child believes they are undeserving of love.

The abused believes they deserve the abuse, that love will always hurt and often comes coated in shame.

The child of addicts learns to fundamentally mistrust the safety and stability of the world around them.

The child raised in a religion that vilifies all human behavior will inevitably see themselves as sinful and unworthy.

Any kind of abuse—emotional, physical, sexual—is often the starting point for a long, twisted, distorted journey from our true selves. And our worldview takes shape around that bad information we’ve deduced because of it.

One of the biggest challenges we face as writers is how to hook our reader emotionally and forge a connection in those first few pages without becoming the literary equivalent of the stranger in the checking line, blurting out every gory detail of the drama of their lives without even having been asked.

The secret, I think, is to show or hint at the character’s contortions and defense mechanisms that have sprung up around that deeper wound. As readers, we’re trained to look for clues and hints, so we’ll spot those coping mechanisms and be intrigued—we’ll want to know why.

So as writers, we need to ask ourselves: In what ways does our character limp through the world? How do they favor that wounded place inside? What distorted belief do they cling to with both hands? What ways do they disassociate from parts of themselves that brush too closely to that wound? In what ways do they wear their wound like a chip on their shoulder, insisting to the world it has made them tough, impervious to future wounding?

And why are these characters indelibly scarred by these events, when others might brush them off or take them in stride?

I believe the answer to that last question is that because for some, the psychic soil has been well prepared and cultivated—their soil broken down and covered in so much manure before the wound even shows up—that the individual is supremely susceptible to the final blow.

But what about characters who don’t have a tragic or traumatic event in their past? What about lesser, garden variety wounds? The kind we acquire from the simple life lessons of growing older or growing up? Because the majority of the time, these shaping wounds are incurred early in life—either in our childhood, teen, or early adult years.

These less traumatic experiences still shape us, although to what degree will vary widely from character to character and will depend on things like the psychic equivalent of adrenaline, momentum, individual pain thresholds, and how cultivated the soil was.

We all have memories from our childhood, of playing with other kids, either on the playground or in the neighborhood, then taking a fall, skinning our knee or scraping an elbow. Chances are we bounced right up and kept on going, utterly impervious to any pain. At least until it was time to come inside and wash up for dinner. THEN we could feel that sucker throbbing and stinging.

Science has also shown that pain thresholds within the same person vary depending on how stressed our systems are. When we are under chronic stress, our body produces a lot more of some chemicals and fewer of others. The reformulation of our brain chemistry intensifies pain response—both physical and emotional.

So even if the story you’re writing does not involve characters with large traumatic wounds in their past, common everyday wounds can be equally fertile ground for deepening character.

- Why does a character have a gambling problem?

- A shopping addiction?

- Why are they terrified of clowns? Cats? Blimps?

- Why do they feel the need to be perfect?

- So competitive?

Each of those behaviors could be fueled by either a traumatic wound or a common every day one. It is the tone and theme of your story that will decide which it should be. Or rather I should say, it is the nature of your character’s wounds that will determine the tone and theme of your story.

We are often our own worst enemy—there is no denying that. Many writers feel that their character is his own antagonist, and that is likely true. Our desperation to avoid acknowledging our wounds, to avoid awakened that old pain and our deeply held beliefs about the nature of that pain are often an enormous component of getting in the way of our own happiness. It is hard and scary to look that deeply inside and reorient our world view, even it if ultimately frees us. It is scary to be thrust back into the same powerlessness and vulnerability we had in that moment. That is why we need stories to show us how.

Some of our character’s most transformative moments will come from facing those wounds, freeing themselves from the weight of them, and beginning the healing process. And of course, the stories we write aren’t about the wounds—but how we can overcome them.

We need stories to show us that being wounded or broken doesn’t lessen our character’s—or our own—humanity in any way. It is, in fact, what make us deeply human. The best stories show us that having been wounded doesn’t mean we are less than, or broken beyond repair, or unworthy. Instead, they illuminate all the different shapes wounds can take and the many different paths to healing that await us, if only we have the courage to look.

Do you know your character’s defining wounds? Can you brainstorm three to four ways these wounds create behaviors that readers can see on the page?

(Originally published on Writer Unboxed April 13, 2018)

Something a little different

This post is a little different from my usual. First up, NIGHT SHIFT DRAGONS is still coming out May 5 in audio and ebook, so hooray! But I'm not actually here to talk about my books today. I'm here to talk about yours.

In addition to being wonderful people with amazing taste in fiction, I know a lot of you are also writers/creative types. Or maybe you just like reading books! Whatever your passion, the last few months have probably been really, really hard on you. I know they've been suck for me, and I'm lucky enough to have a job that keeps me at home all the time anyway.

Staying creative and productive is always hard, but never so much as in times like this. That's why I've teamed up with a bunch of other writers for CONQUERING THE WRITING BLUES, a free online writing conference about staying productive and inspired even when the world is falling apart. There are 25 interviews with a new one emailed out every day starting tomorrow plus a ton of free writing books and other goodies.

Just to be clear: this is a totally free project. I make no money off sign-ups. I just feel very passionate about this topic and wanted to do something to help combat the despair I see in my writing communities. To this end, I've also written a free essay on my website on the same topic called Shining On When the World Is Dark that you can read right now, no extra anything required.

Soap box! I am on you!

Anyway, if you're feeling down and in need of some inspiration, or if you just want to hear a bunch of really cool writers and publishing industry people talking shop, give CONQUERING THE WRITING BLUES a try. My interview goes up this Sunday, and you can see all the other writers on the main site. I just hope you have as much fun listening I had doing the interview, because creativity and writing are my favorite topics ever. Seriously, do not get me started I will talk FOREVER.

Thank you so much as always for being my readers. You folks are the ones who keep me going more than any others when times get tough, and I appreciate you more than words can say. Thank you SO MUCH and see you May 5 for Opal's final book!

Yours,

Rachel Aaron

Recent comments