Authors

Dishhhwashhher

My dearest BDH,

I come to this keyboard today to write to you that we are well. It has been 8 days without a working dishwasher. It is but by the grace of the higher power that we are surviving this crisis. Hope alone sustains us through these dark times, hope that a new dishwasher shall arrive today between the hours of 01:00 PM and 05:00 PM from Wilson Appliances.

Forever yours and deep in dishes,

Ilona, Your Loving Author.

The trouble with the dishwasher started as soon as we came back from vacation. After we got home, I marinated some chicken, and ended up with a load of dishes that had a big glass marinading dish in it.

I start the dishwasher. It gets through part of the cycle. I come back to the kitchen.

DRAIN.

Okay. I have done this song and dance before. I open the dishwasher full of nasty chicken water. Ugh. I get gloves, scoop the water out, take out the filter, clean it out – it’s clean, put it back in, hit the rinse and hold cycle.

DRAIN.

Grrr. I opened the dishwasher, scoop the nasty water out for the second time, remove filter, undo the plastic doohicky that protects a little fan. Sometimes stuff gets stuck under there, preventing the fan from rotating. The fan is clear. Nothing is stuck. Rinse and hold.

DRAIN.

*$##$%%^%$%^.

At that point it was late at night and I didn’t want to wrestle with the chicken water again, so I gave up.

Morning found Gordon messing with the dishwasher. He scooped the chicken water out, checked the filter, checked the fan.

DRAIN.

Maybe there was some grease accumulated somewhere and now things are clogged. We boil water, pour it into the dishwasher. The dishwasher drains. YES! Start the rinse and hold.

DRAIN.

More boiling water.

DRAIN.

DRAIN.

We hoped to have the dishwasher repaired, but nobody works on this brand. We did have a plumber out to check is the hose had clogged.

Plumber: It seems like the motor. How old is this dishwasher?

Gordon: 27 years.

Plumber: This might have something to do with your current problem.

So we bought a new dishwasher. In other news, I have finally finished the nobody knows how old bottle of Dawn’s dishwashing liquid that had been living alone in the dark under the sink.

The house is coming up on 30 years, and so far in the last 18 months the range quit, the fridge bit the dust, and now the dishwasher died.

::eyes the dual ovens::

Between you and me, if they die, I wouldn’t mind, because they are old and the temperature control is questionable. I’m pretty sure 375 is no longer 375. But we are keeping them until they die. They have got to hold on till the mid-fall at least. The Inheritance Buys New Ovens royalties should come in then.

Our smart thermostat quit, but we fixed it and Kid 1’s microwave gave up the ghost, so that concludes the trilogy of appliance breaking. These repairs usually come in threes, so let’s hope this cluster is behind us.

Here is hoping your appliances work well and last way past the manufacturer’s suggested lifecycle.

The post Dishhhwashhher first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Free Fiction Monday: Red Letter Day

Graduation Day at Barack Obama High School. The day the Red Letters arrive. The day that students get a glimpse into their own future.

But a handful never get a letter, and no one knows why. One teacher comes up with an idea though: a teacher who never got a Red Letter herself, a teacher finally finds the answers to her own fate.

Called “a fresh, solid, entertaining take on time travel” by Tangent Online, “Red Letter Day” was chosen as the best short story by the readers of Analog Magazine.

“Red Letter Day“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Red Letter Day By Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Graduation rehearsal—middle of the afternoon on the final Monday of the final week of school. The graduating seniors at Barack Obama High School gather in the gymnasium, get the wrapped packages with their robes (ordered long ago), their mortarboards, and their blue and white tassels. The tassels attract the most attention—everyone wants to know which side of the mortarboard to wear it on, and which side to move it to.

The future hovers, less than a week away, filled with possibilities.

Possibilities about to be limited, because it’s also Red Letter Day.

I stand on the platform, near the steps, not too far from the exit. I’m wearing my best business casual skirt today and a blouse that I no longer care about. I learned to wear something I didn’t like years ago; too many kids will cry on me by the end of the day, covering the blouse with slobber and makeup and aftershave.

My heart pounds. I’m a slender woman, although I’m told I’m formidable. Coaches need to be formidable. And while I still coach the basketball teams, I no longer teach gym classes because the folks in charge decided I’d be a better counselor than gym teacher. They made that decision on my first Red Letter Day at BOHS, more than twenty years ago.

I’m the only adult in this school who truly understands how horrible Red Letter Day can be. I think it’s cruel that Red Letter Day happens at all, but I think the cruelty gets compounded by the fact that it’s held in school.

Red Letter Day should be a holiday, so that kids are at home with their parents when the letters arrive.

Or don’t arrive, as the case may be.

And the problem is that we can’t even properly prepare for Red Letter Day. We can’t read the letters ahead of time: privacy laws prevent it.

So do the strict time travel rules. One contact—only one—through an emissary, who arrives shortly before rehearsal, stashes the envelopes in the practice binders, and then disappears again. The emissary carries actual letters from the future. The letters themselves are the old-fashioned paper kind, the kind people wrote 150 years ago, but write rarely now. Only the real letters, handwritten, on special paper get through. Real letters, so that the signatures can be verified, the paper guaranteed, the envelopes certified.

Apparently, even in the future, no one wants to make a mistake.

The binders have names written across them so the letter doesn’t go to the wrong person. And the letters are supposed to be deliberately vague.

I don’t deal with the kids who get letters. Others are here for that, some professional bullshitters—at least in my opinion. For a small fee, they’ll examine the writing, the signature, and try to clear up the letter’s deliberate vagueness, make a guess at the socio-economic status of the writer, the writer’s health, or mood.

I think that part of Red Letter Day makes it all a scam. But the schools go along with it, because the counselors (read: me) are busy with the kids who get no letter at all.

And we can’t predict whose letter won’t arrive. We don’t know until the kid stops mid-stride, opens the binder, and looks up with complete and utter shock.

Either there’s a red envelope inside or there’s nothing.

And we don’t even have time to check which binder is which.

***

I had my Red Letter Day thirty-two years ago, in the chapel of Sister Mary of Mercy High School in Shaker Heights, Ohio. Sister Mary of Mercy was a small co-ed Catholic High School, closed now, but very influential in its day. The best private school in Ohio according to some polls—controversial only because of its conservative politics and its willingness to indoctrinate its students.

I never noticed the indoctrination. I played basketball so well that I already had three full-ride scholarship offers from UCLA, UNLV, and Ohio State (home of the Buckeyes!). A pro scout promised I’d be a fifth round draft choice if only I went pro straight out of high school, but I wanted an education.

“You can get an education later,” he told me. “Any good school will let you in after you’ve made your money and had your fame.”

But I was brainy. I had studied athletes who went to the Bigs straight out of high school. Often they got injured, lost their contracts and their money, and never played again. Usually they had to take some crap job to pay for their college education—if, indeed, they went to college at all, which most of them never did.

Those who survived lost most of their earnings to managers, agents, and other hangers’ on. I knew what I didn’t know. I knew I was an ignorant kid with some great ball-handling ability. I knew that I was trusting and naïve and undereducated. And I knew that life extended well beyond thirty-five, when even the most gifted female athletes lost some of their edge.

I thought a lot about my future. I wondered about life past thirty-five. My future self, I knew, would write me a letter fifteen years after thirty-five. My future self, I believed, would tell me which path to follow, what decision to make.

I thought it all boiled down to college or the pros.

I had no idea there would be—there could be—anything else.

You see, anyone who wants to—anyone who feels so inclined—can write one single letter to their former self. The letter gets delivered just before high school graduation, when most teenagers are (theoretically) adults, but still under the protection of a school.

The recommendations on writing are that the letter should be inspiring. Or it should warn that former self away from a single person, a single event, or a one single choice.

Just one.

The statistics say that most folks don’t warn. They like their lives as lived. The folks motivated to write the letters wouldn’t change much, if anything.

It’s only those who’ve made a tragic mistake—one drunken night that led to a catastrophic accident, one bad decision that cost a best friend a life, one horrible sexual encounter that led to a lifetime of heartache—who write the explicit letter.

And the explicit letter leads to alternate universes. Lives veer off in all kinds of different paths. The adult who sends the letter hopes their former self will take their advice. If the former self does take the advice, then the kid who receives the letter from an adult they will never be. The kid, if smart, will become a different adult, the adult who somehow avoided that drunken night. That new adult will write a different letter to their former self, warning about another possibility or committing bland, vague prose about a glorious future.

There’re all kinds of scientific studies about this, all manner of debate about the consequences. All types of mandates, all sorts of rules.

And all of them lead back to that moment, that heart stopping moment that I experienced in the chapel of Sister Mary of Mercy High School, all those years ago.

We weren’t practicing graduation like the kids at Barack Obama High School. I don’t recall when we practiced graduation, although I’m sure we had a practice later in the week.

At Sister Mary of Mercy High School, we spent our Red Letter Day in prayer. All the students started their school days with Mass. But on Red Letter Day, the graduating seniors had to stay for a special service, marked by requests for God’s forgiveness and exhortations about the unnaturalness of what the law required Sister Mary of Mercy to do.

Sister Mary of Mercy High School loathed Red Letter Day. In fact, Sister Mary of Mercy High School, as an offshoot of the Catholic Church, opposed time travel altogether. Back in the dark ages (in other words, decades before I was born), the Catholic Church declared time travel an abomination, antithetical to God’s will.

You know the arguments: If God had wanted us to travel through time, the devout claim, he would have given us the ability to do so. If God had wanted us to travel through time, the scientists say, he would have given us the ability to understand time travel—and oh! Look! He’s done that.

Even now, the arguments devolve from there.

But time travel has become a fact of life for the rich and the powerful and the well-connected. The creation of alternate universes scares them less than the rest of us, I guess. Or maybe the rich really don’t care—they being different from you and I, as renowned (but little read) 20th Century American author F. Scott Fitzgerald so famously said.

The rest of us—the non-different ones—realized nearly a century ago that time travel for all was a dicey proposition, but this being America, we couldn’t deny people the opportunity of time travel.

Eventually time travel for everyone became a rallying cry. The liberals wanted government to fund it, and the conservatives felt only those who could afford it would be allowed to have it.

Then something bad happened—something not quite expunged from the history books, but something not taught in schools either (or at least the schools I went to), and the federal government came up with a compromise.

Everyone would get one free opportunity for time travel—not that they could actually go back and see the crucifixion or the Battle of Gettysburg—but that they could travel back in their own lives.

The possibility for massive change was so great, however, that the time travel had to be strictly controlled. All the regulations in the world wouldn’t stop someone who stood in Freedom Hall in July of 1776 from telling the Founding Fathers what they had wrought.

So the compromise got narrower and narrower (with the subtext being that the masses couldn’t be trusted with something as powerful as the ability to travel through time), and it finally became Red Letter Day, with all its rules and regulations. You’d have the ability to touch your own life without ever really leaving it. You’d reach back into your own past and reassure yourself, or put something right.

Which still seemed unnatural to the Catholics, the Southern Baptists, the Libertarians, and the Stuck in Time League (always my favorite, because they never did seem to understand the irony of their own name). For years after the law passed, places like Sister Mary of Mercy High School tried not to comply with it. They protested. They sued. They got sued.

Eventually, when the dust settled, they still had to comply.

But they didn’t have to like it.

So they tortured all of us, the poor hopeful graduating seniors, awaiting our future, awaiting our letters, awaiting our fate.

I remember the prayers. I remember kneeling for what seemed like hours. I remember the humidity of that late spring day, and the growing heat, because the chapel (a historical building) wasn’t allowed to have anything as unnatural as air conditioning.

Martha Sue Groening passed out, followed by Warren Iverson, the star quarterback. I spent much of that morning with my forehead braced against the pew in front of me, my stomach in knots.

My whole life, I had waited for this moment.

And then, finally, it came. We went alphabetically, which stuck me in the middle, like usual. I hated being in the middle. I was tall, geeky, uncoordinated, except on the basketball court, and not very developed—important in high school. And I wasn’t formidable yet.

That came later.

Nope. Just a tall awkward girl, walking behind boys shorter than I was. Trying to be inconspicuous.

I got to the aisle, watching as my friends stepped in front of the altar, below the stairs where we knelt when we went up for the sacrament of communion.

Father Broussard handed out the binders. He was tall but not as tall as me. He was tending to fat, with most of it around his middle. He held the binders by the corner, as if the binders themselves were cursed, and he said a blessing over each and every one of us as we reached out for our futures.

We weren’t supposed to say anything, but a few of the boys muttered, “Sweet!” and some of the girls clutched their binders to their chests as if they’d received a love letter.

I got mine—cool and plastic against my fingers—and held it tightly. I didn’t open it, not near the stairs, because I knew the kids who hadn’t gotten theirs yet would watch me.

So I walked all the way to the doors, stepped into the hallway, and leaned against the wall.

Then I opened my binder.

And saw nothing.

My breath caught.

I peered back into the chapel. The rest of the kids were still in line, getting their binders. No red envelopes had landed on the carpet. No binders were tossed aside.

Nothing. I stopped three of the kids, asking them if they saw me drop anything or if they’d gotten mine.

Then Sister Mary Catherine caught my arm, and dragged me away from the steps. Her fingers pinched into the nerve above my elbow, sending a shooting pain down to my hand.

“You’re not to interrupt the others,” she said.

“But I must have dropped my letter.”

She peered at me, then let go of my arm. A look of satisfaction crossed her fat face, then she patted my cheek.

The pat was surprisingly tender.

“Then you are blessed,” she said.

I didn’t feel blessed. I was about to tell her that, when she motioned Father Broussard over.

“She received no letter,” Sister Mary Catherine said.

“God has smiled on you, my child,” he said warmly. He hadn’t noticed me before, but this time, he put his hand on my shoulder. “You must come with me to discuss your future.”

I let him lead me to his office. The other nuns—the ones without a class that hour—gathered with him. They talked to me about how God wanted me to make my own choices, how He had blessed me by giving me back my future, how He saw me as without sin.

I was shaking. I had looked forward to this day all my life—at least the life I could remember—and then this. Nothing. No future. No answers.

Nothing.

I wanted to cry, but not in front of Father Broussard. He had already segued into a discussion of the meaning of the blessing. I could serve the church. Anyone who failed to get a letter got free admission into a variety of colleges and universities, all Catholic, some well known. If I wanted to become a nun, he was certain the church could accommodate me.

“I want to play basketball, Father,” I said.

He nodded. “You can do that at any of these schools.”

“Professional basketball,” I said.

And he looked at me as if I were the spawn of Satan.

“But, my child,” he said with a less reasonable tone than before, “you have received a sign from God. He thinks you Blessed. He wants you in his service.”

“I don’t think so,” I said, my voice thick with unshed tears. “I think you made a mistake.”

Then I flounced out of his office, and off school grounds.

My mother made me go back for the last four days of class. She made me graduate. She said I would regret it if I didn’t.

I remember that much.

But the rest of the summer was a blur. I mourned my known future, worried I would make the wrong choices, and actually considered the Catholic colleges. My mother rousted me enough to get me to choose before the draft. And I did.

The University of Nevada in Las Vegas, as far from the Catholic Church as I could get.

I took my full ride, and destroyed my knee in my very first game. God’s punishment, Father Broussard said when I came home for Thanksgiving.

And God forgive me, I actually believed him.

But I didn’t transfer—and I didn’t become Job, either. I didn’t fight with God or curse God. I abandoned Him because, as I saw it, He had abandoned me.

***

Thirty-two years later, I watch the faces. Some flush. Some look terrified. Some burst into tears.

But some just look blank, as if they’ve received a great shock.

Those students are mine.

I make them stand beside me, even before I ask them what they got in their binder. I haven’t made a mistake yet, not even last year, when I didn’t pull anyone aside.

Last year, everyone got a letter. That happens every five years or so. All the students get Red Letters, and I don’t have to deal with anything.

This year, I have three. Not the most ever. The most ever was thirty, and within five years it became clear why. A stupid little war in a stupid little country no one had ever heard of. Twenty-nine of my students died within the decade. Twenty-nine.

The thirtieth was like me, someone who has not a clue why her future self failed to write her a letter.

I think about that, as I always do on Red Letter Day.

I’m the kind of person who would write a letter. I have always been that person. I believe in communication, even vague communication. I know how important it is to open that binder and see that bright red envelope.

I would never abandon my past self.

I’ve already composed drafts of my letter. In two weeks—on my fiftieth birthday—some government employee will show up at my house to set up an appointment to watch me write the letter.

I won’t be able to touch the paper, the red envelope or the special pen until I agree to be watched. When I finish, the employee will fold the letter, tuck it in the envelope and earmark it for Sister Mary of Mercy High School in Shaker Heights, Ohio, thirty-two years ago.

I have plans. I know what I’ll say.

But I still wonder why I didn’t say it to my previous self. What went wrong? What prevented me? Am I in an alternate universe already and I just don’t know it?

Of course, I’ll never be able to find out.

But I set that thought aside. The fact that I did not receive a letter means nothing. It doesn’t mean that I’m blessed by God any more than it means I’ll fail to live to fifty.

It is a trick, a legal sleight of hand, so that people like me can’t travel to the historical bright spots or even visit the highlights of their own past life.

I continue to watch faces, all the way to the bitter end. But I get no more than three. Two boys and a girl.

Carla Nelson. A tall, thin, white-haired blonde who ran cross-country and stayed away from basketball, no matter how much I begged her to join the team. We needed height and we needed athletic ability.

She has both, but she told me, she isn’t a team player. She wanted to run and run alone. She hated relying on anyone else.

Not that I blame her.

But from the devastation on her angular face, I can see that she relied on her future self. She believed she wouldn’t let herself down.

Not ever.

Over the years, I’ve watched other counselors use platitudes. I’m sure it’s nothing. Perhaps your future self felt that you’re on the right track. I’m sure you’ll be fine.

I was bitter the first time I watched the high school kids go through this ritual. I never said a word, which was probably a smart decision on my part, because I silently twisted my colleagues’ platitudes into something negative, something awful, inside my own head.

It’s something. We all know it’s something. Your future self hates you or maybe—probably—you’re dead.

I have thought all those things over the years, depending on my life. Through a checkered college career, an education degree, a marriage, two children, a divorce, one brand new grandchild. I have believed all kinds of different things.

At thirty-five, when my hopeful young self thought I’d be retiring from pro ball, I stopped being a gym teacher and became a full time counselor. A full time counselor and occasional coach.

I told myself I didn’t mind.

I even wondered what would I write if I had the chance to play in the Bigs? Stay the course? That seems to be the most common letter in those red envelopes. It might be longer than that, but it always boils down to those three words.

Stay the course.

Only I hated the course. I wonder: would I have blown my knee out in the Bigs? Would I have made the Bigs? Would I have received the kind of expensive nanosurgery that would have kept my career alive? Or would I have washed out worse than I ever had?

Dreams are tricky things.

Tricky and delicate and easily destroyed.

And now I faced three shattered dreamers, standing beside me on the edge of the podium.

“To my office,” I say to the three of them.

They’re so shell-shocked that they comply.

I try to remember what I know about the boys. Esteban Rellier and J.J. Feniman. J.J. stands for…Jason Jacob. I remembered only because the names were so very old-fashioned, and J.J. was the epitome of modern cool.

If you had to choose which students would succeed based on personality and charm, not on Red Letters and opportunity, you would choose J.J.

You would choose Esteban with a caveat. He would have to apply himself.

If you had to pick anyone in class who wouldn’t write a letter to herself, you would pick Carla. Too much of a loner. Too prickly. Too difficult. I shouldn’t have been surprised that she’s coming with me.

But I am.

Because it’s never the ones you suspect who fail to get a letter.

It’s always the ones you believe in, the ones you have hopes for.

And somehow—now—it’s my job to keep those hopes alive.

***

I am prepared for this moment. I’m not a fan of interactive technology—feeds scrolling across the eye, scans on the palm of the hand—but I use it on Red Letter Day more than any other time during the year.

As we walk down the wide hallway to the administrative offices, I learn everything the school knows about all three students which, honestly, isn’t much.

Psych evaluations—including modified IQ tests—from grade school on. Addresses. Parental income and employment. Extracurriculars. Grades. Troubles (if any reported). Detentions. Citations. Awards.

I already know a lot about J.J. already. Homecoming king, quarterback, would’ve been class president if he hadn’t turned the role down. So handsome he even has his own stalker, a girl named Lizbet Cholene, whom I’ve had to discipline twice before sending to a special psych unit for evaluation.

I have to check on Esteban. He’s above average, but only in the subjects that interest him. His IQ tested high on both the old exam and the new. He has unrealized potential, and has never really been challenged, partly because he doesn’t seem to be the academic type.

It’s Carla who is still the enigma. IQ higher than either boy’s. Grades lower. No detentions, citations, or academic awards. Only the postings in cross country—continual wins, all state three years in a row, potential offers from colleges, if she brought her grades up, which she never did. Nothing on the parents. Address in a middle-class neighborhood, smack in the center of town.

I cannot figure her out in a three-minute walk, even though I try.

I usher them into my office. It’s large and comfortable. Big desk, upholstered chairs, real plants, and a view of the track—which probably isn’t the best thing right now, at least for Carla.

I have a speech that I give. I try not to make it sound canned.

“Your binders were empty, weren’t they?” I say.

To my surprise, Carla’s lower lip quivers. I thought she’d tough it out, but the tears are close to the surface. Esteban’s nose turns red and he bows his head. Carla’s distress makes it hard for him to control his.

J.J. leans against the wall, arms folded. His handsome face is a mask. I realize then how often I’d seen that look on his face. Not quite blank—a little pleasant—but detached, far away. He braces one foot on the wall, which is going to leave a mark, but I don’t call him on that. I just let him lean.

“On my Red Letter Day,” I say, “I didn’t get a letter either.”

They look at me in surprise. Adults aren’t supposed to discuss their letters with kids. Or their lack of letters. Even if I had been able to discuss it, I wouldn’t have.

I’ve learned over the years that this moment is the crucial one, the moment when they realize that you will survive the lack of a letter.

“Do you know why?” Carla asks, her voice raspy.

I shake my head. “Believe me, I’ve wondered. I’ve made up every scenario in my head—maybe I died before it was time to write the letter—”

“But you’re older than that now, right?” J.J. asks, with something of an angry edge. “You wrote the letter this time, right?”

“I’m eligible to write the letter in two weeks,” I say. “I plan to do it.”

His cheeks redden, and for the first time, I see how vulnerable he is beneath the surface. He’s as devastated—maybe more devastated—than Carla and Esteban. Like me, J.J. believed he would get the letter he deserved—something that told him about his wonderful, successful, very rich life.

“So you could still die before you write it,” he said, and this time, I’m certain he meant the comment to hurt.

It did. But I don’t let that emotion show on my face. “I could,” I say. “But I’ve lived for thirty-two years without a letter. Thirty-two years without a clue about what my future holds. Like people used to live before time travel. Before Red Letter Day.”

I have their attention now.

“I think we’re the lucky ones,” I say, and because I’ve established that I’m part of their group, I don’t sound patronizing. I’ve given this speech for nearly two decades, and previous students have told me that this part of the speech is the most important part.

Carla’s gaze meets mine, sad, frightened and hopeful. Esteban keeps his head down. J.J.’s eyes have narrowed. I can feel his anger now, as if it’s my fault that he didn’t get a letter.

“Lucky?” he asks in the same tone that he used when he reminded me I could still die.

“Lucky,” I say. “We’re not locked into a future.”

Esteban looks up now, a frown creasing his forehead.

“Out in the gym,” I say, “some of the counselors are dealing with students who’re getting two different kinds of tough letters. The first tough one is the one that warns you not to do something on such and so date or you’ll screw up your life forever.”

“People actually get those?” Esteban asks, breathlessly.

“Every year,” I say.

“What’s the other tough letter?” Carla’s voice trembles. She speaks so softly I had to strain to hear her.

“The one that says You can do better than I did, but won’t—can’t really—explain exactly what went wrong. We’re limited to one event, and if what went wrong was a cascading series of bad choices, we can’t explain that. We just have to hope that our past selves—you guys, in other words—will make the right choices, with a warning.”

J.J.’s frowning too. “What do you mean?”

“Imagine,” I say, “instead of getting no letter, you get a letter that tells you that none of your dreams come true. The letter tells you simply that you’ll have to accept what’s coming because there’s no changing it.”

“I wouldn’t believe it,” he says.

And I agree: he wouldn’t believe it. Not at first. But those wormy little bits of doubt would burrow in and affect every single thing he does from this moment on.

“Really?” I say. “Are you the kind of person who would lie to yourself in an attempt to destroy who you are now? Trying to destroy every bit of hope that you possess?”

His flush grows deeper. Of course he isn’t. He lies to himself—we all do—but he lies to himself about how great he is, how few flaws he has. When Lizbet started following him around, I brought him into my office and asked him not to pay attention to her.

It leads her on, I say.

I don’t think it does, he says. She knows I’m not interested.

He knew he wasn’t interested. Poor Lizbet had no idea at all.

I can see her outside now, hovering in the hallway, waiting for him, wanting to know what his letter said. She’s holding her red envelope in one hand, the other lost in the pocket of her baggy skirt. She looks prettier than usual, as if she’s dressed up for this day, maybe for the inevitable party.

Every year, some idiot plans a Red Letter Day party even though the school—the culture—recommends against it. Every year, the kids who get good letters go. And the other kids beg off, or go for a short time, and lie about what they received.

Lizbet probably wants to know if he’s going to go.

I wonder what he’ll say to her.

“Maybe you wouldn’t send a letter if the truth hurt too much,” Esteban says.

And so it begins, the doubts, the fears.

“Or,” I say, “if your successes are beyond your wild imaginings. Why let yourself expect that? Everything you do might freeze you, might lead you to wonder if you’re going to screw that up.”

They’re all looking at me again.

“Believe me,” I say. “I’ve thought of every single possibility, and they’re all wrong.”

The door to my office opens and I curse silently. I want them to concentrate on what I just said, not on someone barging in on us.

I turn.

Lizbet has come in. She looks like she’s on edge, but then she’s always on edge around J.J.

“I want to talk to you, J.J.” Her voice shakes.

“Not now,” he says. “In a minute.”

“Now,” she says. I’ve never heard this tone from her. Strong and scary at the same time.

“Lizbet,” J.J. says, and it’s clear he’s tired, he’s overwhelmed, he’s had enough of this day, this event, this girl, this school—he’s not built to cope with something he considers a failure. “I’m busy.”

“You’re not going to marry me,” she says.

“Of course not,” he snaps—and that’s when I know it. Why all four of us don’t get letters, why I didn’t get a letter, even though I’m two weeks shy from my fiftieth birthday and fully intend to send something to my poor past self.

Lizbet holds her envelope in one hand, and a small plastic automatic in the other. An illegal gun, one that no one should be able to get—not a student, not an adult. No one.

“Get down!” I shout as I launch myself toward Lizbet.

She’s already firing, but not at me. At J.J. who hasn’t gotten down.

But Esteban deliberately drops and Carla—Carla’s half a step behind me, launching herself as well.

Together we tackle Lizbet, and I pry the pistol from her hands. Carla and I hold her as people come running from all directions, some adults, some kids holding letters.

Everyone gathers. We have no handcuffs, but someone finds rope. Someone else has contacted emergency services, using the emergency link that we all have, that we all should have used, that I should have used, that I probably had used in another life, in another universe, one in which I didn’t write a letter. I probably contacted emergency services and said something placating to Lizbet, and she probably shot all four of us, instead of poor J.J.

J.J., who is motionless on the floor, his blood slowly pooling around him. The football coach is trying to stop the bleeding and someone I don’t recognize is helping and there’s nothing I can do, not at the moment, they’re doing it all while we wait for emergency services.

The security guard ties up Lizbet and sets the gun on the desk and we all stare at it, and Annie Sanderson, the English teacher, says to the guard, “You’re supposed to check everyone, today of all days. That’s why we hired you.”

And the principal admonishes her, tiredly, and she shuts up. Because we know that sometimes Red Letter Day causes this, that’s why it’s held in school, to stop family annihilations and shootings of best friends and employers. Schools, we’re told, can control weaponry and violence, even though they can’t, and someone, somewhere, will use this as a reason to repeal Red Letter Day, but all those people who got good letters or letters warning them about their horrible drunken mistake will prevent any change, and everyone—the pundits, the politicians, the parents—will say that’s good.

Except J.J.’s parents, who have no idea their son had no future. When did he lose it? The day he met Lizbet? The day he didn’t listen to me about how crazy she was? A few moments ago, when he didn’t dive for the floor?

I will never know.

But I do something I would never normally do. I grab Lizbet’s envelope, and I open it.

The handwriting is spidery, shaky.

Give it up. J.J. doesn’t love you. He’ll never love you. Just walk away and pretend that he doesn’t exist. Live a better life than I have. Throw the gun away.

Throw the gun away.

She did this before, just like I thought.

And I wonder: was the letter different this time? And if it was, how different? Throw the gun away. Is that line new or old? Has she ignored this sentence before?

My brain hurts. My head hurts.

My heart hurts.

I was angry at J.J. just a few moments ago, and now he’s dead.

He’s dead and I’m not.

Carla isn’t either.

Neither is Esteban.

I touch them both and motion them close. Carla seems calmer, but Esteban is blank—shock, I think. A spray of blood covers the left side of his face and shirt.

I show them the letter, even though I’m not supposed to.

“Maybe this is why we never got our letters,” I say. “Maybe today is different than it was before. We survived, after all.”

I don’t know if they understand. I’m not sure I care if they understand.

I’m not even sure if I understand.

I sit in my office and watch the emergency services people flow in, declare J.J. dead, take Lizbet away, set the rest of us aside for interrogation. I hand someone—one of the police officers—Lizbet’s red envelope, but I don’t tell him we looked.

I have a hunch he knows we did.

The events wash past me, and I think that maybe this is my last Red Letter Day at Barack Obama High School, even if I survive the next two weeks and turn fifty.

And I find myself wondering, as I sit on my desk waiting to make my statement, whether I’ll write my own red letter after all.

What can I say that I’ll listen to? Words are so very easy to misunderstand. Or misread.

I suspect Lizbet only read the first few lines. Her brain shut off long before she got to Walk away and Throw away the gun.

Maybe she didn’t write that the first time. Or maybe she’s been writing it, hopelessly, to herself in a continual loop, lifetime after lifetime after lifetime.

I don’t know.

I’ll never know.

None of us will know.

That’s what makes Red Letter Day such a joke. Is it the letter that keeps us on the straight and narrow? Or the lack of a letter that gives us our edge?

Do I write a letter, warning myself to make sure Lizbet gets help when I meet her? Or do I tell myself to go to the draft no matter what? Will that prevent this afternoon?

I don’t know.

I’ll never know.

Maybe Father Broussard was right; maybe God designed us to be ignorant of the future. Maybe He wants us to move forward in time, unaware of what’s ahead, so that we follow our instincts, make our first, best—and only—choice.

Maybe.

Or maybe the letters mean nothing at all. Maybe all this focus on a single day and a single note from a future self is as meaningless as this year’s celebration of the Fourth of July. Just a day like any other, only we add a ceremony and call it important.

I don’t know.

I’ll never know.

Not if I live two more weeks or two more years.

Either way, J.J. will still be dead and Lizbet will be alive, and my future—whatever it is—will be the mystery it always was.

The mystery it should be.

The mystery it will always be.

___________________________________________

“Red Letter Day“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Red Letter Day

Copyright © 2021 by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

First published in Analog Science Fiction and Fact Magazine, September, 2010

Published by WMG Publishing

Cover and Layout copyright © 2021 by WMG Publishing

Cover design by WMG Publishing

Cover art copyright © Szefei/Dreamstime, Ingvar Bjork/Dreamstime

This book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. All rights reserved. This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

The Inheritance: Chapter 5 Part 2

We have some tense chapters ahead. Remember, this is not a tornado that will rip your house apart. This is a well-maintained rollercoaster that passed all of the safety inspections with flying colors. It might be scary, but you will walk away from this ride.

Thank you for the numerous offers to “pay for the story right now.” It is so gratifying.

The Inheritance will be available as an ebook pretty soon. Meanwhile, we would really appreciate you spreading the word and recommending this serial to your friends and other readers you know. Thanks again for suggesting the Royal Road a means to reach a wider audience, but unfortunately The Inheritance probably isn’t LitRPG enough to fit there.

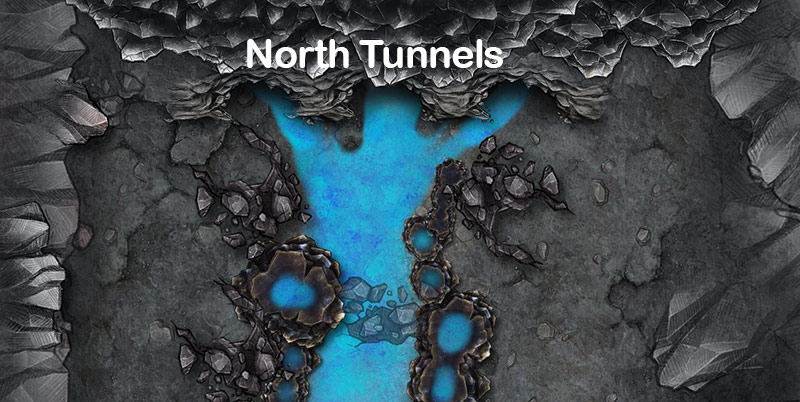

There was no way down.

I had scanned the darkness three times. It was a bottomless pit. No route below, no ledges we could drop down to, no escape. The only path out was the same way we came. Through the passage and back into the lake dragon’s cavern.

I gave it about five minutes after the last of the noises faded, and then Bear and I snuck forward to the mouth of the tunnel. We made it just in time to see the lake dragon pull the bug’s corpse under the water. It would be busy for a while. As long as we avoided the shore, we should be safe.

I searched the perimeter of the cave, staying as far from the lake as I could. There were no other tunnels, but there was a path up, along a ledge that climbed fifty feet above the cavern floor. We took it and picked our way onto a natural stone bridge. It brought us across the cavern to a dark fissure in the opposite wall, barely three feet wide. We squeezed through it, and it spat us out into a wide tunnel.

Ahead the passageway gave way to a large natural arch, and through it I could see more ledges and passages, a warren of tunnels, some dark, some marked by bioluminescence. Unlike the banks of the river, studded with jagged rocks, the floor of the tunnel was relatively flat, with ridges of hard stone breaking through here and there like ribs of some buried giant skeleton. Fossilized roots braided through solid rock between the stone ribs. The air smelled sour and acrid.

Next to me, Bear took a few steps to the side and sniffed something. I focused on it. Stalker poop.

“No,” I whispered and tugged the leash.

She came back and looked at me with slight disapproval. Sniffing strange poop was what dogs did, and I was clearly preventing her from fulfilling her duty.

I could see the other signs now: the faint trail leading to the fissure, more feces, stains from urine on the rocks. These tunnels were stalker hunting grounds. They came through here and took the bridge down to the water below, and because the banks of the river was hard to get to, some of them made their way to the lake to drink. The lake dragon nabbed them like a crocodile ambushing wildebeests.

This wasn’t just a cave stuffed with random monsters. This was an ecosystem. The lake dragon was an apex predator; the giant bug was probably a rank below, and the stalkers were mid-tier. There must be prey species somewhere in these tunnels. There was certainly enough vegetation to support small herbivores.

What were the breaches? Nobody could definitively answer that question, and there was a lot of debate about whether they had been artificially made by the invaders or if our enemy somehow plucked a section of existing reality and wedged it between our worlds.

I could see the pale stains on the rocks, where stone had been bleached by generations of stalkers urinating on it. None of this environment looked new. This was an established bionetwork that developed over years, possibly centuries. All of this had to have belonged somewhere, to a different world.

This was the longest I had ever been in a breach and the furthest I had gone into one. Assault teams spent days, sometimes weeks in the breaches, but my normal MO was to get in, find the resources, and get out. I had no idea if all breaches were like this, but if they were, what would happen to this place when the anchor was destroyed? Did this environment disintegrate, or did it simply return to its place of origin?

I almost felt something, a memory or a trace of knowledge, just outside my reach. A kind of amorphous feeling, like trying to remember a dream. I nearly understood it, but it slipped from my grasp and was gone.

Officially there were thirty-two times when a breach collapsed while people were still inside. Sixty percent of those were considered fatal events – nobody made it out. In the rest of the cases, some people were jettisoned back to the point of the gate’s origin. A large percentage of those survivors showed brain damage with retrograde amnesia. Some had to relearn basic skills like writing and holding a spoon.

Sooner or later, Cold Chaos would put another assault team into this breach. I had to get out before they shattered the anchor.

Bear growled softly.

I flexed. Four shapes were closing in on us, sneaking through the gloom. My talent grasped them, and knowledge came flooding in. The re-nah. Fast, deadly, able to regurgitate acidic bile that would burn exposed skin on contact. Pack hunters, cautious alone, brazen in large numbers. The strongest of the group would attack first, drawing attention, while the rest would flank the prey. Their hearts, on the right side, were possible to reach with a long narrow blade, but the best target was at the base of their throat, just under their chin. A small organ that functioned like a secondary motor cortex. It made them fast and helped them coordinate their movements when they swarmed, and when damaged or destroyed, it induced partial paralysis.

A memory unfurled. A clearing in a deep alien jungle, stalkers streaming from the caves in the mountain side, forming a massive horde. Eyes glowing, fangs bared, two males fighting, each trying to rip out the other’s throat…

I reached down and released Bear’s leash.

Around us the cave was perfectly silent, except for the faint sound of water dripping somewhere out of sight. The bracer on my wrist flowed into my hand, its metal familiar by now, slightly textured and comfortable, like a favorite kitchen knife I had used for years. I focused on the blade. Long, flat, an inch and a half wide. As much damage as possible in a single thrust. The organ would be hard to hit on a moving target. Still better than a heart, though.

Drip. Drip. Drip.

There were no thoughts anymore. I just stood still and waited.

Drip. Drip.

Almost there. They were crouching along the walls, measuring the distance, shifting forward, paw over paw. One large male, two smaller ones, and a female hugging the left wall.

Drip.

The large male charged. He tore out of the gloom like a cannonball, jaws gaping. There was no time to think. I just reacted. My sword slid into the soft tissue of his neck. The male crashed, its momentum carrying him forward despite his locked limbs. Somehow I dodged, and then Bear was on him. The stalker was twice her weight and almost twice her size, but his legs no longer worked. She ripped into his throat, tearing at the wound I’d made.

The remaining males lunged, one from the left, the other from the right. The right one came high, snarling and loud, while the one on the left silently aimed for my legs. I sliced from right to left, turning as I cut. The sword caught the right stalker across the muzzle, carving a bright gash. The stalker recoiled, but I kept going, cutting as I twisted. The blade caught the stalker on the left, slicing through his flesh. There was almost no resistance. The left stalker yelped and scuttled back on three legs, its front left leg severed clean.

Bear ripped into the left stalker. The right one pivoted and charged toward her. I sprinted, slicing like my life depended on it. The right stalker’s head slid off its shoulders.

Bear and the other stalker were a clump of fur and teeth, rolling on the ground. I flexed, willing the moment to stretch out like a rubber band. It did. The frantic whirlwind of bodies slowed, and I narrowed my sword into a spike, and drove down into the base of the stalker’s neck. It went limp.

Time snapped back. A terrible weight smashed into my back. My knees buckled. Scalding teeth sank into my right shoulder.

Pain tore through me, turning into an ice-cold rage.

I turned the sword into a dagger, bent my elbow, and stabbed the blade straight into the female stalker’s face. She dropped off me, backing away to the fissure. I chased her, blood running down my arm. She made it all the way through the gap before I caught her. She spun to face me and bared her teeth, her nose wet with blood. I bore down on her and kicked as hard as I could. My foot connected with her head. She stumbled back and slid off the stone bridge. For a moment she hung on, digging her claws into the bare rock, but her talons slipped, and she plunged into the river below.

Bear. Shit.

I spun around and sprinted back into the tunnel. The three stalker bodies lay unmoving. Bear sat in the middle. Her shoulder was bloody, and there was a long streak of red across her right side. She panted, her eyes bright, her mouth opened in a happy canine smile, like she just ran around through the surf on some beach and was now waiting for a treat.

She saw me, grabbed the smallest stalker by the paw, and tried to drag it toward me. Hi, I’m Bear and these are my dead stalker friends. Look how fancy.

I dug into my pocket, fished some jerky out, and offered it to her. She took it from my fingers, dropped it to the ground, went back to the stalker, bit it some more, came back, and ate the jerky.

“Good girl, Bear. Best girl.”

We were both bleeding, but we were still alive. Four stalkers! We took down four…

I should be dead. And Bear should’ve been dead with me. It took the assault team a bucket of bullets to stop eight stalkers, and Bear and I killed four. A creature the size of a Great Dane had jumped on my back, and I stayed upright. It should’ve knocked me off my feet.

It wasn’t just the weird hallucination and the unusual precision of my talent. I was changing. Physically changing.

The thought pierced me like a jolt of high-voltage current. The hair on the back of my neck rose.

The year after the divorce had twisted me. I used to like flying. In my head, flying was married to vacation, because flights of my childhood took me to the beach and amusement parks. Suddenly I was terrified to board a plane. The fear was so debilitating, I couldn’t even talk while boarding. I became obsessed with traffic, avoiding driving whenever I could. I developed a fixation on my health that bloomed into hypochondria.

I ended up in therapy, where we got to the root of the problem. I had realized that Roger was truly, completely gone and if something happened to me, the kids would be alone. I was desperately trying to exert control over my environment, and when I failed, my body locked up and refused to respond. It took years to get over it, and the hypochondria was the hardest to defeat. Every time I thought I’d finally broken free, it would come back with a vengeance over some minor thing like a new mole or some weird pain in my arm.

In a way, becoming an assessor was the best thing for me. Facing death every week didn’t leave room for anxiety. I was too busy surviving.

In this moment, it was like all those years of therapy, exercise, and rewiring my brain’s responses never happened. Was I dying? Was that glowing thing eating at me like cancer? No doctor would be able to get it out of me. There was no treatment for whatever the fuck it was. What if I wasn’t human anymore? What if I got back to the gate and it wouldn’t let me exit back to Earth?

The grip of anxiety crushed me. I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t move, I just stood there, desperately cataloging everything happening in my body. My breathing, my aches and pains, the strange electric prickling feeling in my fingers. I could hear my own heartbeat. It was fast and so loud…

A cold nose nudged my hand.

I still couldn’t move.

Bear pushed her muzzle into my fingers, bumping me. I felt her fur slide against my hand.

Bump. Bump.

I exhaled slowly. The air escaped out of me, as if it had been trapped in my lungs. I swallowed, crouched, and hugged Bear. Gradually the sound of my heart receded.

Yes, I was changing. No, I had no control over it and I didn’t know what I would become at the end of this process. But I was getting stronger. There were four stalker corpses on this cave floor. I made that happen.

I petted Bear, straightened, walked over to the nearest furry body, and flexed. One hundred and fifty-seven pounds. I grabbed the stalker by the front paws and lifted it off the ground. My shoulder whined in protest. I clenched my teeth against the pain.

I was holding one hundred and fifty-seven pounds of dead weight. It wasn’t resting on my back, no, I was holding it in front of me.

I wonder…

I spun around and threw the corpse. The stalker flew and landed on the cave floor. My shoulder screeched, and I grabbed at it. Okay, not the brightest moment.

The stalker corpse lay 10 feet away. I threw one hundred and fifty-seven pounds across ten feet. Two weeks ago, I’d used a forty-five-pound plate for some overhead squats at the DDC gym, because someone was hogging the Smith machine, and I had a hard time holding it steady for 10 reps.

“We’re not in Kansas anymore, Bear.”

Bear looked at me, padded over to the corpse I threw, and bit it.

“No worries. It’s dead. You are the best girl, Bear, you know that?”

Somewhere in the tangle of the tunnels a creature howled. We couldn’t stay here. We had to keep moving.

I pulled the antibacterial gel out, slathered some on my bleeding shoulder, popped 4 Motrins, and turned to Bear.

“Okay, girl, let’s treat your battle wounds.”

The post The Inheritance: Chapter 5 Part 2 first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Monday Meows

Please to be joining my peer network.

Hokay, peering.

I am the slightly alarmed peer.

Hey, alarmed is my gig!

I never really liked peers. I’m more of an apples guy.

Leviathan Limited Edition from Lividian

Signed, Numbered, and Slipcased Limited Edition

Includes cover and interior artwork by Vincent Chong

Just Announced and Selling Very Quickly!

Lividian Publications is proud to be publishing a deluxe signed, numbered, and slipcased Limited Edition hardcover of Leviathan by Robert McCammon, the final volume in his acclaimed Matthew Corbett series. This deluxe special edition tips the scales at more than 500 pages and has been lavishly crafted with collectors and readers alike in mind. Vincent Chong provided stunning color artwork for the dust jacket along with a full-color frontispiece and exclusive black and white illustrations for the interior!

Don’t forget that our books are also carried by some of our favorite small presses and retailers:

Bad Moon Books

Buchheim Verlag (Germany)

Camelot Books

Cracked and Spineless Books (Australia)

Jake’s Rare Books

Kathmandu Books

Midworld Press

Overlook Connection

SST Publications (UK)

Subterranean Press

Veryfinebooks

Ziesings

The Inheritance: Chapter 5, Part 1

Note: commercial airlines fly at 30,000 feet. Private jets fly higher, with the midsize jets specifically flying at 41,000-45,000 feet.

The plane shuddered as it hit an air pothole. Elias put his hand on the maps spread out in front of him on the table to keep them from sliding off. Across from him, Leo sat very still, his eyes unblinking. His XO didn’t like planes. It wasn’t the flying; it was the lack of control. And if he mentioned it, Leo would just feel more self-conscious and withdraw deeper. Comfort and logic didn’t work for times like these, but distraction did wonders.

Elias turned his attention back to the maps. The sooner he sorted through his thoughts, the faster he could put Leo’s sharp mind to analyzing the Elmwood disaster instead of focusing on being stuck in a metal tube hurtling through the atmosphere 40,000 feet above the ground.

Gate dives had stages. Of all of them, the Assault phase was the main and most important. Humanity entered the gates to destroy the anchor and collapse the breach. Everything else was secondary to this goal, no matter how much some people wanted to twist it. Yes, mining paid the bills, but the focus of the mission was to keep the invasion at bay.

Like many others, Elias felt the anchor the moment he stepped through the gate. It tugged on him, a knot of energy, a distant nexus of power that demanded attention. The stronger you were, the more it pulled on you. Not every gate diver sensed it, and the majority of those who did barely felt it. To them it was a spark, a firefly winking somewhere in the distance. To Elias, it was inescapable, like an evil sun. It called to him, and he hunted it down until he cut through its defenders, forced his way into the anchor chamber, and shattered it.

The trick wasn’t just carving a bloody path to the anchor. The real challenge was to destroy the breach and come out alive. Successful gate dives required preparation. It began with the DDC, who measured the energy emissions of a gate, graded its threat level, and assigned a DeBRA and a guild.

Once Cold Chaos received the assignment, the gate became their problem. An assault team, a mining crew, and an escort was determined, and a gate coordinator was chosen to handle the logistics and keep everything running smoothly.

The assault team deployed to the gate and began the first official phase, the Survey. They progressed carefully into the breach and identified the most likely route to the anchor and promising mining areas. They cleared the mining sites, mapped as much of the immediate environment around them and the gate as was feasible, and came back out.

The next stage was called R&R: Rest and Regroup. Each breach was unique. Open air biomes required larger groups. Cave biomes called for a smaller force with higher individual firepower. Some people didn’t do well in dark enclosed spaces. Others couldn’t swim or had trouble with heights. The assault team reshuffled its roster based on their findings. They reviewed their survey with the escort captain, the mining foreman, and the DeBRA, and then they rested for 24 hours.

After the R&R, the Assault stage finally began. The assault team went back into the breach, swept the mining site one more time, sent a scout back to give the mining team an all-clear, and pressed on toward the anchor. An hour after they entered, the mining crew, the DeBRA, and the escort walked into the breach, made their way to the mining site, and began stripping. A rich site would mean a steady flow of carts filled with resources out of the gate.

If everything went according to plan, the assault team would reach the anchor and destroy it. Without the energy of the anchor, the breach would begin to degrade. The assault team would have to haul ass to the gate, usually sending a scout ahead to warn the mining team to wrap up operations. The breach typically collapsed within 12-36 hours.

That wasn’t what happened in Elmwood.

Radio communications did not work in the breaches, so every assault team carried a “cheesecake,” a beeper stone. Beeper stones occurred in the steppe and mountain biomes and had a core of denser material running through them. When shocked with electricity, they glowed and vibrated. If you broke a piece off and then shocked the core of the main stone, the broken-off piece would also light up and vibrate. Distance didn’t seem to matter. As long as both fragments were in the same breach, shocking the core would activate the other chunk. The first gate diver who discovered this effect compared it to the Cheesecake Factory’s restaurant pager and the name stuck.

The moment the cheesecake was activated, the assault team would know that a fatal event occurred, and they were being recalled. It was the breach equivalent of an SOS. They would turn around and head back for the gate.

The mining crew died less than an hour after entering the gate. As soon as London and the rest made it out, the gate coordinator went into the breach with the core stone, shocked it, and then returned to shock the core stone every half hour for three hours. The assault team was barely two hours into their trek to the anchor. They never came out. It meant only one thing: everyone was dead.

Elias peered at the mining site map. Compasses didn’t work in the breaches, so traditional directions didn’t exist. Instead, the moment you entered, you faced north and the gate behind you was always due south. It was obviously simplified but it worked, and all breach maps followed this principle.

The cave biomes were Elias’ least favorite, and this one was a fucking maze. A tangle of tunnels, passages, and chambers, resulting from eons of erosion as water shaved and carved the stone.

Some people theorized that the breaches were artificial, generated environments, constructed specifically to invade Earth. He never believed in the artificial breach theory. It was bullshit. He’d gone into too many breaches and seen too much. The complexity of the bio systems they encountered was incredible, far too intricate for any artificial construct. No, the breaches were chunks of some other world, maybe worlds, complete with their inhabitants and their own weird rules of survival. And this breach was a perfect example of that. It was old and filled with valuable deposits and extremely dangerous hostiles.

On the surface, Malcolm, the leader of the assault team, had followed the Cold Chaos protocol. The assault team surveyed, they R&R’d, they reentered and swept the mining site for the second time, then started toward the anchor. But the more Elias looked into what actually happened, the wonkier it appeared.

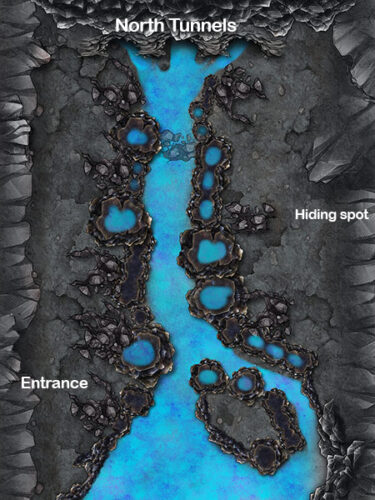

The map in front of him showed Malcolm’s chosen anchor route, which ran almost straight north into the breach. The mining site lay off to the east, roughly a mile from the gate, at the end of a branching tunnel. It was a massive cavern with a stream running north to south. The map showed an entrance in the lower left, through which the mining crew accessed the site, and three tunnels in the north, at the top of the map. The assault team had mapped the tunnels up to half a mile, revealing a tangle of passageways, pits, chambers, and tunnels, half of them carrying running water.

Map of the Mining Site

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

Determining a good mining area was more art than science. The Cold Chaos guidelines for cave biomes dictated that only the larger caverns could be designated as mining sites. The guild lost too many people in tunnel collapses. The mining site had to be safe and defendable, it couldn’t be too far from the gate, and it had to have a good mix of promising minerals identifiable by sight and an abundance of vegetation in case the minerals turned out to be trash. The weirder the site looked, the more promising it would be.

Things would have been so much simpler if they could hire their own assessors, Elias reflected. As it was, they were forced to play the guessing game. That’s why most assault teams identified at least 3 sites.

Malcolm had only picked one.

Elias examined the top edge of the cavern one more time.

Nothing in this world was free. They were never going to go into a breach with fluffy bunnies and rare, priceless resources. The unspoken rule was, the more valuable the find, the harder it would be to extract. Malcolm knew this. He wasn’t sloppy, he wasn’t careless, and yet here they were.

Elias looked at Leo. His XO leaned forward slightly.

“You are Malcolm,” Elias said.

Leo nodded.

Most people assumed that the tank was always the leader. Something about a warrior putting themselves in the path of a threat and soaking up damage while shielding others naturally lent itself to the leader role in people’s imagination. In reality, tanks were almost always too focused on combat to be effective leaders. They were the tip of the spear, and they usually had their hands full.

His own Talent, the Blade Warden, straddled the line between a tank and a damage dealer. He could play either role. On paper, he paid for this versatility with reduced effectiveness. A pure tank Talent, like Sentinel or Protector, of the same power level, could take more damage than Elias. A pure damage dealer, a Pulsecarver or a Stormsurge like Leo, would wreck more havoc. But in the breach, the value of his versatility skyrocketed. He had led teams while tanking – he would do it again in Elmwood – but given a choice, he preferred to go in with a dedicated tank.

Most team leaders were either midfielders or ranged fighters. The ability to survey the terrain was paramount.

Malcolm was an Interceptor, a maneuverable, fast damage dealer. He positioned himself behind the tank, which allowed him to rapidly respond to the changing battlefield. He fought with a spear, could summon plasma javelins, which he hurled at incoming threats, and could teleport about twenty yards once every hour or so.

The man had an uncanny situational awareness. He was slightly precognizant, anticipating the enemy’s actions as well as his team’s. He could predict how and where an opponent would attack and how his people were likely to respond to it. He sensed when someone would need assistance, and he was always where he was needed the most. His only flaw as a team leader was that occasionally he made impulsive decisions. Nine times out of ten, he reacted as expected but once in a while he would roll the dice. To his credit, he was good enough to compensate when his gamble didn’t pay off, but he’d come close to disaster a couple of times.

Elias tapped the map of the mining site. “You find this site. You sweep it. It’s clean. Your next move?”

“I set up aetherium charges in these three tunnels and detonate.”

Exactly. “Why?”

Leo swept his fingers across the three passages veering and branching off, some paths spiraling, others ending abruptly.

“It’s a mess. Everything is connected. The only way to secure the mining site is to prevent access completely. One way in, one way out.”

“Agreed. Malcolm would have known that.”

“Yes.”

The two of them peered at the map. This was basic shit, and yet Malcolm left the tunnels as they were.

“Why?” Elias murmured.

“I don’t know.”

“What’s your best guess?”

Leo considered the map. “Perhaps he was unsure whether he picked the right path to the anchor and thought he might have to double back and take one of the tunnels instead.”

“Yes, but with the firepower in that team and the mining crew’s equipment, he could easily reopen one of the entrances after collapsing it. Why gamble with the miners’ lives?”

Leo shook his head. “I don’t know.”

“Next question: why only one mining site? The protocol suggests at least three. Why this one?”

Leo thought about it. “You think he found something in that cave? Something he had to have?”

“That’s the only thing that would make sense.”

In Malcolm’s place, Elias would have spent another three days on a survey and then doubled back and collapsed those tunnels. Then and only then would it have been safe to bring in the miners. Yes, there would be red tape, and they would have to explain to the DDC why they took their time, but in the end, lives wouldn’t be lost. Instead, Malcolm charged in, pushing the mining crew to the site as soon as the guild regulations allowed.

Leo eyes flashed white. The moment he was left to his own devices, he would take a deep dive into Malcolm’s life. Leo took mysteries as a personal challenge,

Elias leaned back. “Let’s say Malcolm glitched out for some reason. He gets impulsive once in a while, but London doesn’t.”

Leo nodded. “London is careful and risk averse.”

Risk averse. Interesting way to put it. Elias would have to remember that.

The XO frowned. “When the team came out with the survey, London would’ve had to sign off on it. He is the escort captain.”

“Exactly. Did you ask him about it?”

“No. It didn’t occur to me.” A hint of frustration showed on Leo’s face. He was his own worst critic. “I should have. It seems obvious in hindsight.’

The intercom came to life. “We’re beginning our descent into Dallas.”

“Don’t worry too much about it,” Elias said. “London isn’t going anywhere. In a few hours we will ask him about that. And a lot more.”

Leo nodded and buckled his seat belt.

The post The Inheritance: Chapter 5, Part 1 first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Benedict

In reply to Kevin.

There’s no such thing as a Primal sigl that increases your essentia count. There are ones that let you store personal essentia, which lets you simulate a higher essentia capacity, but you don’t get something for nothing – you have to pay that essentia in first (and it’ll de-attune quickly unless you do something to stop it). Also, if your plan is to use multiple sigls at once, you have to actually have enough channelling skill to make effective use of them, which a lot of people don’t.

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Kevin

In reply to Benedict.

Ah I should have clarified better!

I meant could you activate a strong enough Primal sigl to increase your essentia count, so you could activate three more. Thus using four activated sigls at once.

But I am guessing from your answer that is not feasible for most Drucrafters unless in cases where you have 2.8 or above Essentia Capacity where that is practical.

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Benedict

In reply to Kevin.

You can use as many sigls as you want – you can use ten if you like – but unless you’ve got a superhuman essentia capacity, you’re only going to have enough essentia to actually activate 2.5 to 3 of them at once, same as anyone else.

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Kevin

Very informative as always, with this info it makes me wonder if Tobias and Helen are using Essentia Capacity prejudice as an excuse for why they are not the heirs.

On the topic of Essentia Capacity, and since I love loophole abuses is it possible to use four sigls at once with one of them being a Primal sigl increasing essentia to “trick the body” as it were into thinking it can use three sigls?

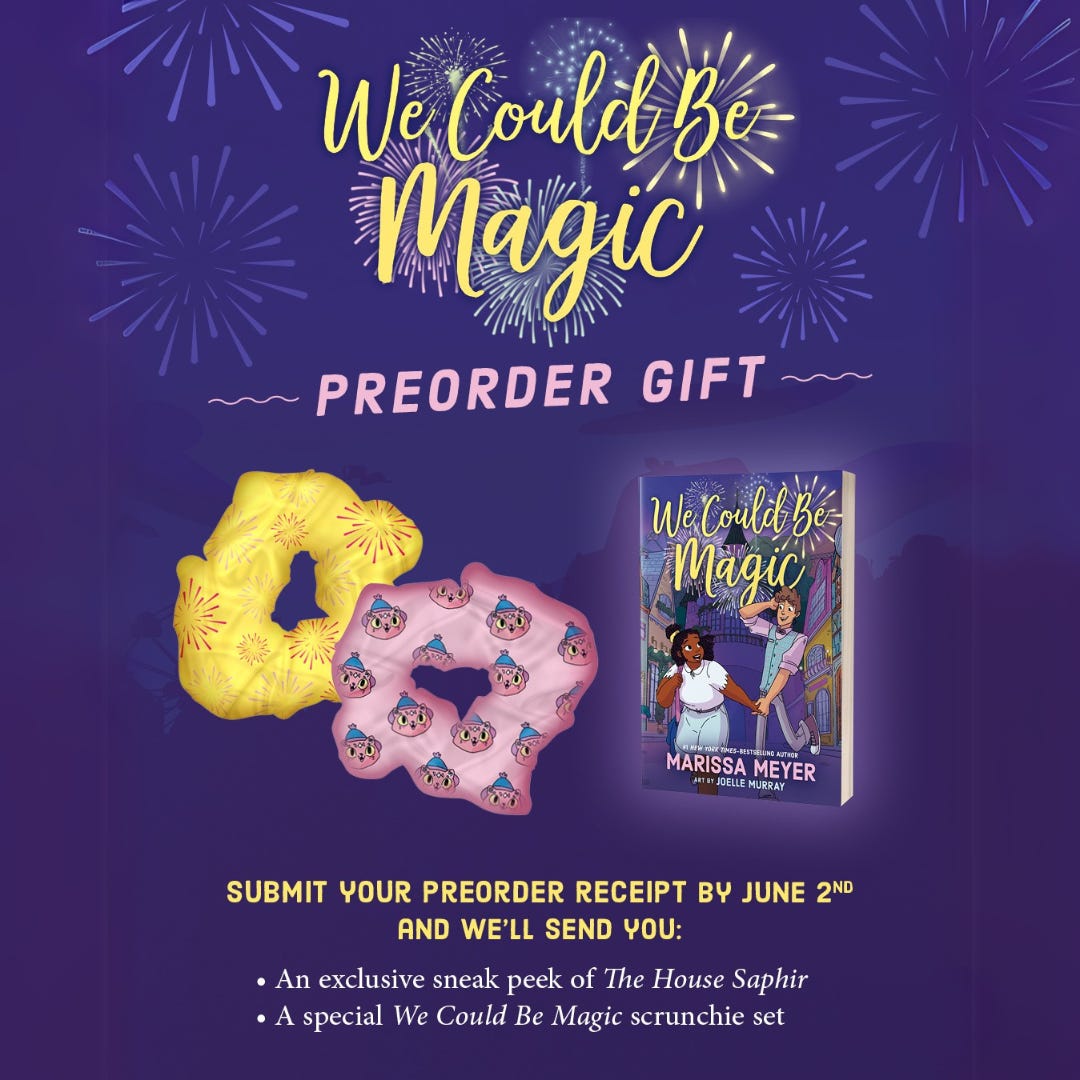

We Could Be Magic Tour, Preorder Goodies, and Upcoming Giveaways!

Happy Spring! It’s nearly time for the release of WE COULD BE MAGIC, my new swoony YA graphic novel, and I have goodies to share!

There is a preorder campaign going on now for readers in the US and Canada. Preorder your copy and upload your receipt to receive these special items below:

• An adorable scrunchie set inspired by the book

• An exclusive digital sneak peek of THE HOUSE SAPHIR (my next fairy tale retelling, coming out this fall!)

A swoon-worthy young adult graphic novel about a girl’s summer job at a theme park from #1 New York Times bestselling author Marissa Meyer.

When Tabitha Laurie was growing up, a visit to Sommerland saved her belief in true love, even as her parents’ marriage was falling apart. Now she’s landed her dream job at the theme park’s prestigious summer program, where she can make magical memories for other kids, guests, and superfans just like her. All she has to do is audition for one of the coveted princess roles, and soon her dreams will come true.

There’s just one problem. The heroes and heroines at Sommerland are all, well… thin. And no matter how much Tabi lives for the magic, she simply doesn’t fit the park’s idea of a princess.

Given a not-so-regal position at a nacho food stand instead, Tabi is going to need the support of new friends, a new crush, and a whole lot of magic if she’s going to devise her own happily ever after. . . without getting herself fired in the process.

With art by Joelle Murray, the wonder of Sommerland comes to life with charming characters and whimsical backdrops. We Could Be Magic is a perfect read for anyone looking to get swept away by a sparkly summer romance.

How to get your swag:

- Preorder your copy via my Bookshop.org store (or wherever you normally purchase your books).

- Submit your receipt here. US/Canada only. See link for full details.

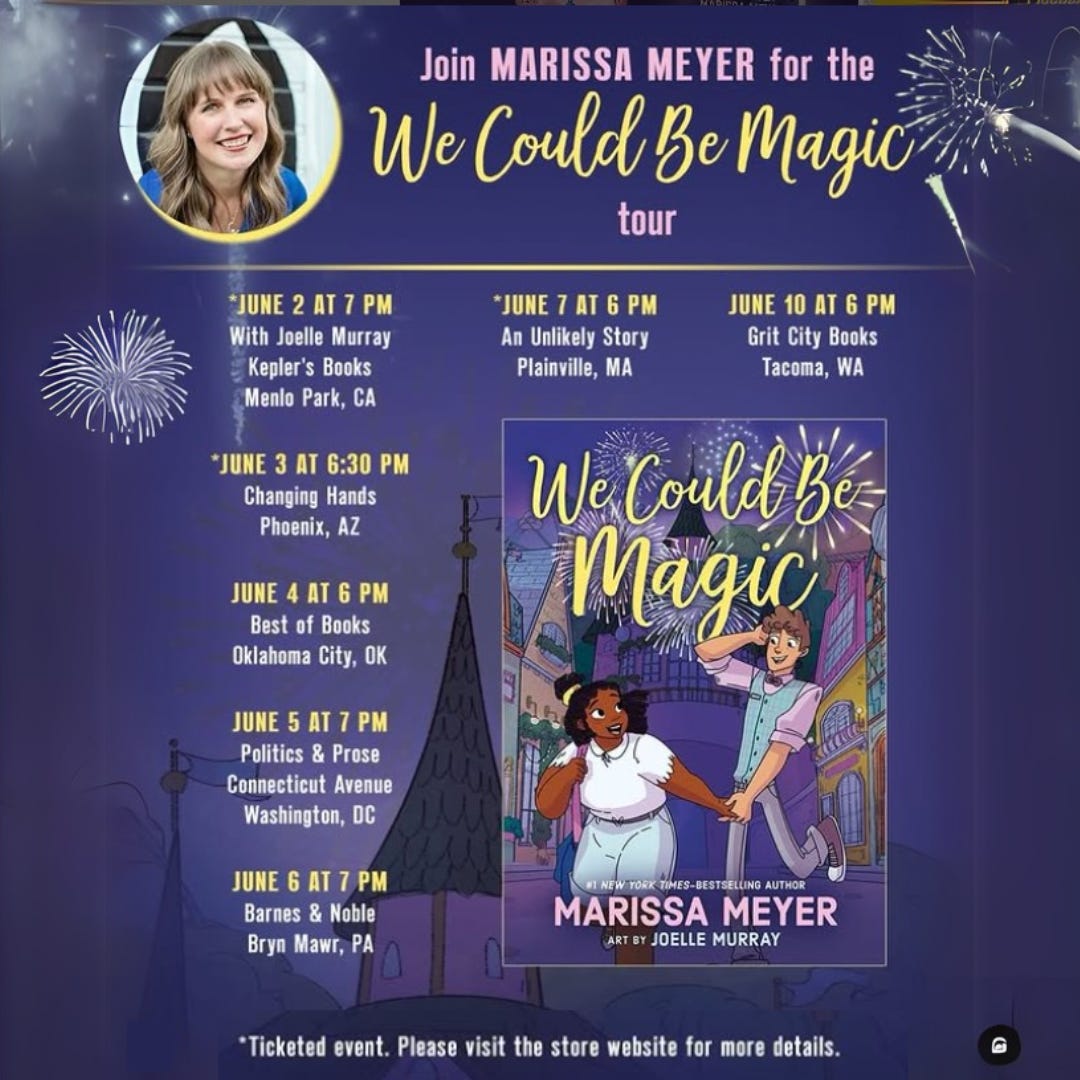

I’m going on tour and hope to see you!

See the special tour linktree for individual event details and ticketing.

The House Saphir

The House Saphir

I know many of you are anxiously awaiting THE HOUSE SAPHIR. Not only is there an exclusive sneak peek coming for those who preorder WE COULD BE MAGIC, but other giveaways are coming, including a romance inspired one over on Instagram, so make sure you follow me to get the latest.

THE HOUSE SAPHIR comes out November 4, but you can add it to Goodreads now and preorder your copy from my store at Bookshop.org (or wherever you get your books). Don’t forget to keep those receipts *hint, hint*.

Until next time, happy reading and I hope to see you soon on the WE COULD BE MAGIC tour!

With love,

Marissa

The post We Could Be Magic Tour, Preorder Goodies, and Upcoming Giveaways! first appeared on Marissa Meyer.

OUT NOW – The Counterfactual War

The Protectorate – an interdimensional empire that has conquered five timelines so far – has set its sights on ours. Led by a man willing to risk everything for power and conquest, armed with technology a hundred years ahead of ours – technology promising salvation to its allies and doom to its enemies – and drawing on a far deeper military history, the Protectorate Expeditionary Force has arrived to invade and incorporate our world into the greatest empire the multiverse has ever known, or die trying.

The United States has won a desperate battle against the crosstime invaders, but large swathes of the country remain under enemy occupation, the struggle to understand invader technology has barely begun and a new invasion force has appeared in the Middle East. As the country staggers and threatens to collapse, the military prepares for a major offensive that could make or break the war, while – deep in the heart of Texas – the invaders prepare a plan of their own …

One battle has been won. The war is far from over.

Download a FREE SAMPLE, then purchase from Amazon US, UK, CAN, AUS, Books2Read.

Back to Life, Back to Reality and Book Recommendation

The vacation was amazing. The air was 80F. The ocean was 80F. The pools were great. The room was spectacular. The food was delicious. The drinks were to die for.

We went on a date to this restaurant that was technically part of the resort but set outside of the grounds, by a busy street. We sat on a terrace, under a canvas, watched the foot traffic and listened to a remarkably good live singer. At some point I had a moment of wondering if this was actually happening. It’s been so long since we had a vacation. Last year, we had a weekend in Daytona. That was it. I needed this in the worst way.

We swam so much. I miss it already.

We are back home, and the dishwasher drainage line is clogged. We’ve taken the dishwasher apart, checked the fan, and have done the boiling water trick, so it looks like we have to get a plumber involved. Reality, coming like a freight train.

Professional NewsThis Kingdom is a hot potato. We have now sold the rights to 5 foreign countries, most of which we cannot contractually disclose yet, but we are free to say that we will be working with Tor UK. We are very excited.

We have seen the cover sketches. They sent 3 sketches and all three were great. We picked a favorite and can’t wait to see it in color and detail. I don’t want to jinx it, so I won’t say more.

Book RecommendationI usually don’t read while we work. It’s very hard to shift gears from concentrating on the narrative to enjoying it. While on vacation, though, I downloaded a series through Kindle Unlimited and I glomed it. I’ve read 4.5 books at this point. Big thanks to Matt, Alisha, Sauron, and Christy for recommending the Azarinth Healer series.

Ilea likes punching things. And eating.

Unfortunately, there aren’t too many career options for hungry brawlers. Instead, the plan is to quit her crappy fast-food job, go to college, and become a fully functioning member of society. Essentially – a fate worse than death.

So maybe it’s lucky that she wakes up one day in a strange world where a bunch of fantasy monsters are trying to kill her…?

On the bright side, ‘killing those monsters right back’ is now a viable career path! For she soon discovers her new home runs on a set of game-like rules that will allow her to punch things harder than in her wildest dreams. Well, maybe not her wildest dreams, but it’s close.

With no quest to follow, no guide to show her the way, and no real desire to be a Hero – Ilea embarks on a journey to discover a world full of magic. Magic she can use to fight even bigger monsters.

She’s struggling to survive, has no idea what will happen next, and is loving every minute of it. Except, and sometimes also, when she’s poisoned and/or has set herself on fire. It’s complicated.

Read the story that took Royal Road by storm with over 60 million views and counting.

It’s a classic LitRPG, the stats, the battles, the violence. A prefect beach read for me. I really enjoyed the action. The protagonist is endearing and is authentically a 20 year old. The world is imaginative and exciting. The Silver Rose dungeon was chef’s kiss. I’m a horrible harpy who hates everything, and I couldn’t stop reading it. If you like LitRPG, this is a good one.

For the romance readers: there is none. There is some casual sex with the door closed.

There is an audiobook and it is good. I listened to about half of the first one on the plane.

Fair warning for people fresh to the genre: this series concentrates a lot on the battles. You get very detailed blow by blow fights. I like battles and there were times my eyes started glazing over. Like if you think our fight scenes are too long, these are much more detailed.

Here is the link to Amazon: Azarinth Healer. There is always another drake.