Feed aggregator

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #35: Introduction to Essentia Capacity by Celia

In reply to Skeeve.

Seems like the easiest way to hold a drucrafter captive would be to just take all their sigls. Barring some primal effects, they wouldn’t be able to actually use their essentia for anything then. (Assuming they didn’t do anything odd like imbed a sigl subcutaneously or swallow it.)

Goth Chick News: Oh Deer – Bambi Goes Berserk in The Reckoning

Bambi: The Reckoning (ITN Studio, July 25, 2025)

Bambi: The Reckoning (ITN Studio, July 25, 2025)

File this one in the “Why the F?” folder.

Bambi: The Reckoning is a British indie horror flick directed by Dan Allen and written by Rhys Warrington. It marks the fourth disturbing entry in The Twisted Childhood Universe (TCU), which brought us Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey and is now turning Felix Salten’s beloved deer into a forest-dwelling force of vengeance.

The Brits must really hate us.

Starring Roxanne McKee, Tom Mulheron, Nicola Wright, Samira Mighty, Alex Cooke, and Russell Geoffrey Banks, The Reckoning twists the tale of Bambi into a blood-soaked revenge story. The premise? A grieving, mutated Bambi — yes, you read that right — goes on a rampage after his mother’s untimely demise, targeting a hapless mother and son caught in his antlered crosshairs.

Though I’m not suggesting you do it, here’s the trailer if you want a look.

The project was first teased back in November 2022, when Bambi: The Reckoning was announced as the latest horror romp to traumatize a generation raised on wholesome animated classics. Helmed by Jagged Edge Productions, the film takes inspiration from the eerie creature design in Netflix’s The Ritual, because apparently, we all needed Bambi to double as nightmare fuel. Producer Scott Jeffrey described the flick as “an incredibly dark retelling” of Salten’s 1928 book, with our once-gentle deer transformed into a “vicious killing machine that lurks in the wilderness.”

Production kicked off in London on January 6, 2024, and filming wrapped just twenty days later — let me show you my shocked face.

Bambi: The Reckoning is set to hit U.S. theaters on July 25, 2025, so mark your calendars and prepare to binge-watch the Disney Channel that day instead.

Life and Other Dishes

I have a weird feeling this week. It’s like I overlooked something or forgot some bill, and I keep checking to see what I missed and can’t find it. And it’s Thursday already. How? How?

Gordon’s surgery is next week. They will clean the scar tissue from his shoulder, and he will have to immediately go into physical therapy. If we miss an Inheritance installment, that’s probably why. Hopefully we will stay on track. I am going to try to get the next three posts lined up so Mod R can just click Publish and then do the hard work of moderating.

To people asking about craft projects: I haven’t been able to knit or crochet because the hands are not cooperating. Especially the wrist rotation with the hook is a no go. I haven’t been able to see a neurologist either. I can’t even get on the schedule. It is a bit frustrating. Okay, it’s very frustrating.

I need to get back to workouts. I chickened out this week because we are having a heat wave. It’s overcast today and it cooled off to 96, wooo! We were at 101F (38C) yesterday. It’s hot and humid. I think lifting weights was helping a little or maybe it’s my imagination.

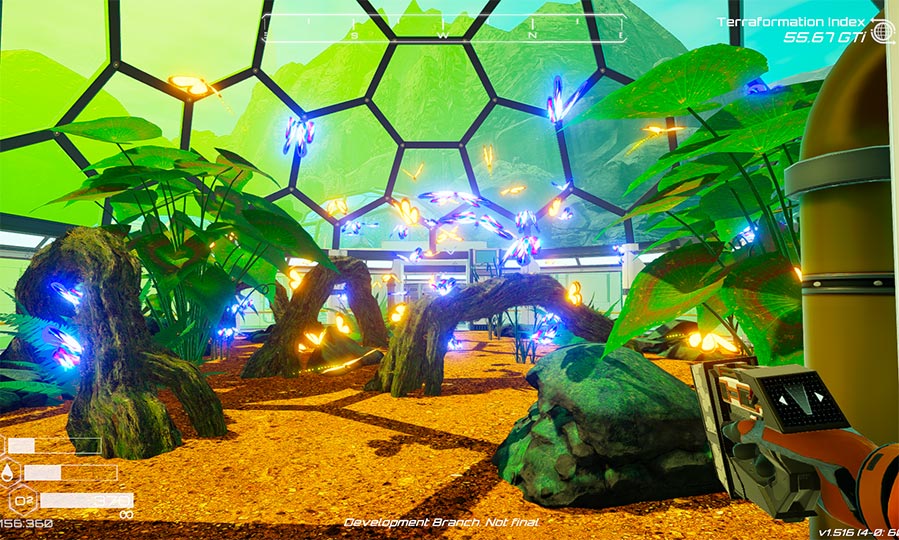

Since I can’t knit or crochet, I’ve been trying to play a little bit of computer games, although I have to limit that, too. Both Planet Crafter and the Enshrouded are releasing updates: the Enshrouded one already came out, and the Planet Crafter is coming on 16 or 19th.

I have been playing the Humble expansion in Planet Crafter in preparation for the expansion. It’s a neat game where you are a convict dropped off on a barren rock of a planet, and the only way to escape is to terraform it into a garden planet.

Right now I’m breeding butterflies in different colors. The game is pretty, although Humble isn’t my favorite. I like a lot of water at my base locations, and the centrally located lake is more like a puddle.

My butterflies!

My butterflies!

My bees!

My bees!

Zeolite crystal mining site

Zeolite crystal mining site

Cool Sinkhole. There is a cave behind the large waterfall.

Cool Sinkhole. There is a cave behind the large waterfall.

The new update is supposed to let you terraform more moons in this alien solar system. I’m excite!

Finally, we have gotten a couple of puzzled comments – mostly from international readers – regarding the widespread use of dishwashers in US. About 75% of US households have them. They are convenient, and we are encouraged to purchase them because they use less water. A typical modern dishwasher will use 3-4 gallons for a load of dishes, while washing the same load by hand uses 15-27 gallons. It also saves energy, because most people wash their dishes in hot water and heating that water adds up. To that one commenter who wondered why an off-the-grid home in the Southwest would need one – their water is likely limited. They are trying to conserve their resources. A small dishwasher can ran off solar, and washing dishes is not optional.

To the person who is now vigorously typing how their handwashing never uses that much water: Having a dishwasher doesn’t make you lazy, not having one doesn’t make you a dirty planet polluter. It’s a convenient appliance. Some people have space for it, some don’t, and there is no reason to have a moral superiority battle over it.

I’m trying to figure out what to read next. LitRPG is my new military SF. I usually read outside of the genre I’m working on and I’m unlikely to ever write a strict LitRPG. I am sadly out of the Azarinth Healer. I have Bushido Online in my library for some reason. Maybe I will try that one next.

The post Life and Other Dishes first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Spotlight on “Ecstasy” by Ivy Pochoda

Ecstasy is a deliciously dark horror reimagining of a Greek tragedy, by Ivy Pochoda, and…

The post Spotlight on “Ecstasy” by Ivy Pochoda appeared first on LitStack.

Review: Level: Ascension by David Dalglish

Buy Level: AscensionRead our review of Book 1, Level: Unknown

FORMAT/INFO: Level: Ascension was published by Orbit Books on May 13th, 2025. It is 400 pages long and available in ebook, audiobook, and paperback formats.

OVERVIEW/ANALYSIS: In order to save his world, Nick will have to end another. With a large black disc traveling closer and closer to his research station, Nick spends nearly all his time in the fantasy world of Yensere, a digital simulation created by a mysterious alien artifact. In Yensere, the god-king Vaan has frozen a similar looking black sun in the sky; this has prevented an apocalypse in Yensere but disrupted the patterns of time and nature in a way that seems to be destroying the world anyway, if more slowly. If Nick is to understand the doom that approaches his people, he will have to kill the god-king Vaan and unleash disaster on Yensere so that he can gain whatever knowledge he can. But before then, he'll have to defeat the god-king's chosen champions - a task that will come with a devastating cost.

Level:Ascension continues to expand its world in interesting ways, but the plot was overwhelmed by the sheer number of fight sequences. On the plus side we get to learn more about Frost, her origin, and how her sister went missing. It added some much needed personal stakes to the story beyond the also important "save the world." I also appreciated the teases we get indicating that Yensere isn't the only digital world contained within the alien artifact.

But these small nuggets of clues and character insight were overwhelmed by fight after fight after fight. On the one hand, I understand that a LitRPG is going to have a lot of battles in it, especially when it's inspired by a game like Dark Souls. Going from one epic fight to another is literally what that game genre is all about. But the more fights you have with everyone wielding awe-inspiring powers, the less exciting each encounter feels.

Don't get me wrong, in a vacuum the individual fights are impressive. As always, this author delivers a powerhouse finale that is a great set piece with personal stakes. But I could have used one or two fewer fights and a little more time expanding on some of the other characters. Sir Gareth, for instance, was a strong part of book one, but gets a bit left by the wayside in this sequel, a hazard of several new characters entering the playing field.

CONCLUSION: For some of you, hearing that Level: Ascension is chock full of impressive fight scenes is going to be fantastic news, and I encourage you to go give this series a try! For me, while I enjoy the overall concept of this simulated world, I had a bit of trouble finding the momentum in this particular outing. Perhaps with everything coming to a head in upcoming Level: Apocalypse, I'll find that momentum once more.

Magic Triumphs Sample Bonanza

Magic Triumphs, the final novel in the Kate Daniels main series, will be available in full dramatized audio from Graphic Audio on the 20th of May.

That’s eleven instalments (including Magic Gifts) of determination, heykittykittyness, blood, grit, immortal apple pie, and Atlanta mayhem, each one adapted with a full cast, original score, immersive sound effects, and enough snark to satisfy even Kate herself.

If you’ve never listened to a Graphic Audio adaptation before, it’s a full production, a “movie in your mind,” with actors voicing every character. Michael Glenn sacrificed vocal chords to roar like Curran. Nora Achrati basically became Kate, and adapted and directed every book with the same love we have for our favorite gal. KenYatta Rogers would get even Jim’s seal of approval. And the fights? You hear every bone crunch and magic burst.

Next Tuesday, the series will be complete, after a journey that became in 2023. Small Magics will be released with all the KD extras as well as original works like Retribution Clause, Grace of Small Magics, Of Swine and Roses on June 12th.

But wait … completed series doesn’t mean it’s OVER! Kate would never!

Exciting AnnouncementThe Wilmington Years series AND Blood Heir will both be getting the GA treatment, with Nora at the helm, in the first half of 2026!

Thank you to everyone who chalantly pressured fluffily suggested to GA that they continue adaptations in the Kate world and helped to make them audio cult classics.

The Horde is powerful, the Horde is mighty. The Horde, as usual, gets things done.

Until then, we’re celebrating with SIX exclusive audio clips from Magic Triumphs, more sample extravaganza than we’ve ever been able to share before!

A rude awakening:

Fear the Greeks, especially when they’re at your door in a panic:

I love him, you love him, but especially I love him, the best Dark Volhv of all:

Dum-dum-dum-DUUUUUUUMMM! The entrance, the drama, the llama!

It’s an impossible choice, but one of the best scenes of the series, I think. GO, DADDY!

Nobody likes nonconsensual dragons, dude!

Now it’s your turn: tell me which moment you’re most looking forward to from the dramatized Magic Triumphs?

The post Magic Triumphs Sample Bonanza first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

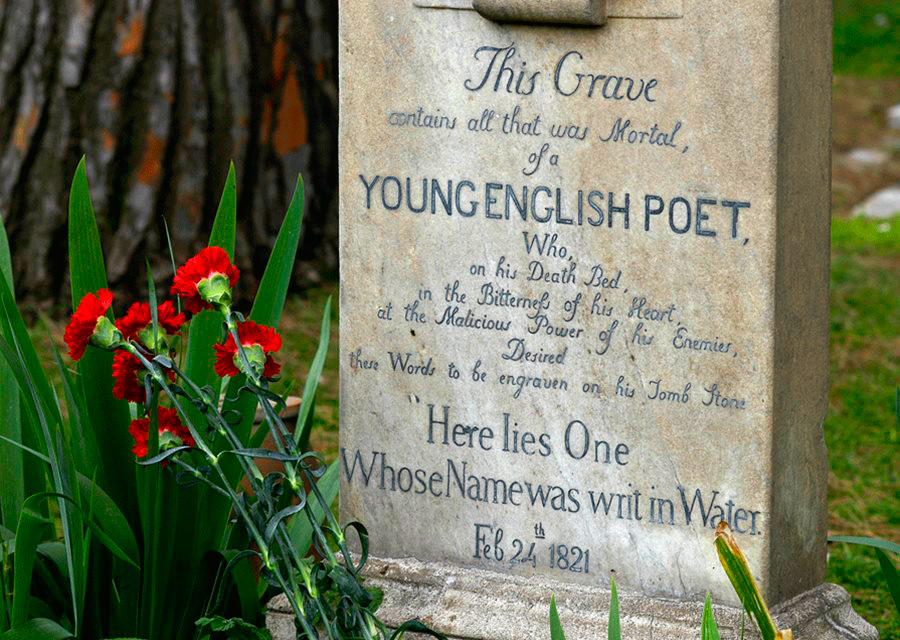

Writ in Water: V.E. Schwab’s The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue

How many times have you heard (or even repeated) the old adage, “Be careful what you wish for?” Of course it’s a cliché, a commonplace beloved of parents and primary school teachers the world over, but such chestnuts sometimes actually contain the distilled wisdom of the human race, and you ignore them at your peril, as is demonstrated (or not, maybe) in Victoria Elizabeth Schwab’s 2020 dark fantasy, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue. It’s a spirited, stimulating read that gives you something to think about.

The story begins in a small French Village, Villon-sur-Sarthe, on a summer evening in 1714. A young woman named Addie LaRue is “running for her life.” Her family has affianced her to an inoffensive but crushingly dull young man. Addie, however, doesn’t want her life to be yet one more colorless copy of the bland existence that her mother (and her mother before her, and her mother before her, and her mother before her…) has led.

Addie has occasionally gone with her carpenter father (who she is closer to than she is to her unsympathetic mother) on business trips to a neighboring town, and these all-too-rare glimpses of the world outside have sparked something in the young woman. She wants to see Paris, she wants to see the world, she wants to go where she will and love who she will. Looking around the well-known, changeless streets of her home, they look more and more like the bars of a prison; she knows that’s not what she wants. She knows she wants more.

Addie’s dreams and ambitions have been (somewhat equivocally) encouraged by an old woman of the village, Estelle Magritte, who is considered by some to be a witch. Estelle talks to Addie about the ancient, elemental, unpredictable gods of the fields and the forest, but she gives the girl one piece of very serious advice:

The old gods may be great, but they are neither kind nor merciful. They are fickle, unsteady as moonlight on water, or shadows in a storm. If you insist on calling them, take heed: be careful what you ask for, be willing to pay the price. And no matter how desperate or dire, never pray to the gods that answer after dark.

It’s counsel that Addie might have been better off heeding.

Fleeing her wedding, Addie plunges into the woods; as she goes deeper into them, the voices of her pursuing family grow fainter and fainter until they disappear. Addie falls to the ground, exhausted, and desperately begins to pray to the only source of help that she can think of, the old gods that Estelle has told her about, but more time has passed than she thinks; she doesn’t realize that the sun has set and that she is calling into the darkness.

Her plea is answered by one of the capricious, compassionless gods that Estelle warned her against, and though he may be inhuman, he at least has an ironic sense of humor, as he comes in the form of the fantasy lover that the lonely Addie “has conjured up a thousand times, in pencil and charcoal and dream.”

Congratulations — you are now the proud owner of a Ford Fiesta! All it will cost you is your soul!

Congratulations — you are now the proud owner of a Ford Fiesta! All it will cost you is your soul!

After the being asks if she is prepared to pay the price for his services, Addie makes the fatal promise, “I will pay anything.” The entity, be it god, devil, or something so entirely other that it cannot fit into either of those common categories, asks her why she is willing to do this. The girl replies with what amounts to her manifesto:

“I do not want to belong to someone else,” she says with sudden vehemence. The words are a door flung wide, and now the rest pour out of her. “I do not want to belong to anyone but myself. I want to be free. Free to live, and to find my own way, to love, or to be alone, but at least it is my choice, and I am so tired of not having choices, so scared of the years rushing past beneath my feet. I do not want to die as I’ve lived, which is no life at all. I –”

The being (which she will soon name Luc) cuts her short. He’s not interested in what she doesn’t want. Can she tell him what it is that that she does desire? That’s easy; Addie wants more time. Luc puts the wish into words for her — “You ask for time without limit. You want freedom without rule. You want to be untethered. You want to live exactly as you please.”

“Yes,” Addie says… but Luc declines the deal. After all, what’s in it for him? He gives her life unending, and he gets nothing? It’s hardly fair. And in that moment, Addie hears again the voices of her family and the other villagers, searching for her, growing louder, coming closer. And in that last moment, she recklessly stakes everything. “You want an ending,” she says. “Then take my life when I am done with it. You can have my soul when I don’t want it anymore.”

Deal.

The rest of the book shows us what kind of life Addie has purchased, and it does so with a forward/backward structure that alternates chapters showing that life in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries (she spends most of the early eighteenth-century chapters discovering exactly what sort of covenant she has entered into), and chapters set in New York City in 2014.

What is the nature of the bargain Addie has made? (Of course, Luc’s deal comes with small print — there’s always small print.) As is common in such transactions, it soon becomes clear that Luc has given her exactly what she asked for. She wanted complete freedom, a radically unfettered life; she wanted no obligations to anyone, and her “benefactor” has found the perfect way to grant her wish.

Addie is free to go where she will, free to do what she wants, free to spend her time in the company of whomever she pleases, and people are drawn to the beautiful, bewitching young woman with the constellation-like pattern of seven freckles on her face. They love her when they’re with her. But when she leaves the room for more than a few minutes, or when they do, or when they fall asleep…

They completely forget her; she vanishes from their minds and memories as thoroughly as if she had never existed. In an especially painful twist, people are unable to even speak her real name.

As the years pass and Addie travels far and wide, she leaves her narrowly circumscribed life in her stultifying little village far behind, and she indeed sees the world — but the cruel nature of her bargain makes it impossible for the world to see her. She finds herself living a rootless, utterly transitory existence which is, in the words of John Keats’ pathetic epitaph, “writ in water.”

Through all these restless centuries, Addie lives by theft (which bothers her, but what else can she do), finds temporarily vacant houses or apartments to stay in for a day or a week, and establishes relationships as transitory as the lives of mayflies. For the first few decades, Luc appears every year to see if Addie is ready to surrender her soul. She always refuses, even as she finds herself looking forward to these visits — who else can she have a real conversation with? Luc’s visits eventually become much more sporadic (despite the hints of a growing and ambiguous attraction between the two, especially on Luc’s part; perhaps it is not good for even a god to be alone). Neither the human nor the inhuman are in a hurry; after all, they both have nothing but time.

Even in the midst of her exile, Addie takes heart from knowing that she has managed to leave some subterranean traces in the world after all, in the works of artists she has briefly known. Luc has been unable to prevent a ghostly record of Addie from appearing in a painting here, or in a song there. This helps her to hang on despite her unassuageable weariness. (That, and she’s just damned stubborn.)

The story makes a major shift in the second half of the book, when, in present-day New York, Addie meets a young man named Henry who works in a used bookstore. He is the one Addie has been waiting hundreds of years for; miraculously, he can remember her. (Addie discovers this when she tries to steal a book.)

Addie and Henry quickly fall in love, or at least, Addie sees that as a real possibility. (For her, he’s the only game in town.) But why is he different? Why can he remember her? The answer turns out to be simple — he, too, has made a deal, and is therefore living outside the boundaries of normal human existence.

Henry’s dilemma was the opposite of Addie’s — the youngest son of a prosperous, successful family, he always felt overlooked, ignored, invisible. No one ever saw him for who he really was. When he proposes to a young woman he has fallen in love with, she turns him down, making it clear that he’s nice and all that, but ultimately he’s not all that important to her. Shattered, Henry decides to commit suicide, but before he can complete the act, Luc appears with an offer: instead of being a person people see through, Henry will become a man no one can miss. Whenever anyone looks at him, they will see whatever they most desire. To everyone he meets, he will be the most important person in the world.

You see the problem, don’t you? Henry, of course, doesn’t, and he accepts the deal.

Now when people look at him, speak to him, have sex with him with glaze-eyed delight, they’re not really seeing him at all; they’re seeing an embodied fantasy that has nothing at all to do with the actual Henry Strauss, and the young man ultimately finds himself more even isolated and desolate than he was before.

This why Henry can remember the ephemeral Addie and why Addie can see the actual Henry — the bargains that they struck perfectly complement each other; their hells dovetail seamlessly.

One difference, though, is that Henry didn’t drive a very hard bargain; his contract isn’t open-ended, and when he meets Addie, the bill is about to come due. Henry has just over a month to live.

A few days before Henry is to die, Luc appears to Addie for the first time in thirty years. Does he know that he finally has her where he wants her? Maybe so, because Addie then finds out the terms of Henry’s contract, and having at last found someone she can willingly sacrifice herself for, she proposes a new bargain: she asks Luc to give Henry (who is “the one piece of her story that she can save”) his life back.

If Luc does this for her, Addie tells him, “I will be yours, as long as you want me by your side.”

Done.

The story ends two years later with Addie browsing in a London bookstore. She hears a customer ask for a copy of a hot new novel that’s making quite a stir. Written by an anonymous author, it is titled The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue.

Finding a copy herself, Addie tremblingly looks at the dedication page; it bears just three words: I Remember You.

Addie knows then that she has won her gamble, and when Luc appears and they walk out of the bookstore together, she thinks that the god who seemingly brought her to bay has been too clever by half. She has an unlimited amount of time in front of her, all the time in the world, time enough to work on Luc as he worked on her, time to “ruin him,” to “break his heart,” to “drive him mad, drive him away.” All the time there is, to make him willingly “cast her off.”

Then, and only then, Addie LaRue will have what she desperately desired so long ago. Finally, she will be free.

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue is an engaging and highly imaginative book, but I do have a couple of quibbles. Addie’s discontent and (especially) the way she thinks about it and acts on it seem more like that of someone born at the end of the twentieth century than of someone born at the end of the seventeenth. Truly entering into the thought-world of a person of such a radically different era is a difficult task (perhaps especially so in our highly “presentist” age) and I can’t say that Schwab has entirely pulled it off. (I also think that kind of portrait wasn’t something she was really aiming at.)

Also, I was less than enthralled with the second half of the book’s “current-day” sections, which largely became one long episode of Young Brooklyn Romance, which, if it isn’t a hit new Netflix series, probably soon will be. In any case, it’s not the sort of thing that winds up at the top of my watch list. With the entrance of Henry, the book moves from things I’m more interested in (explorations of what freedom is and what it’s for, and of the relationship between community and identity — to what extent do we even exist except in relation to other people?) to something I’m less interested in (urban love among the achingly trendy). I say this understanding that I’m not a part of the target demographic of either the novel or the hypothetical show — and by the way, if anyone uses my title, they had better pay me.

Those complaints aside, the story Schwab tells is consistently engaging and entertaining, and at times even thought-provoking. The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue gains much of its power from being a lively new variant on a very old tale and by maintaining its connection with countless myths and stories that have gone before; the novel contains echoes of Faust, The Picture of Dorian Gray, The Wandering Jew, The Flying Dutchman, The Devil and Daniel Webster, and Peter Pan, to name just a few, and Addie can stand unembarrassed in their august company.

Two more recent stories that Addie LaRue also reminded me of are Lolly Willowes, Sylvia Townsend Warner’s 1926 novel of a woman who becomes a witch and sells her soul to the Devil in order to do exactly what Addie wanted — live her own life. Warner was a major writer in many different modes and Lolly Willowes is a masterpiece of double-edged irony, but even though Schwab’s book operates on a less profound level than Warner’s, it’s still not a stretch to speak of them both in the same breath.

Also, Luc strikes me as being at least a cousin of that malevolent aristocrat of Faerie, the Gentleman with the Thistle-Down Hair of Susanna Clarke’s wonderful Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, though the Gentleman is frightening in ways that Luc can’t begin to match. (No person in their right mind would contemplate for an instant having a relationship, romantic or otherwise, with the Gentleman.)

Reading The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue and thinking about the questions it raises brought to mind something that Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, once wrote:

People do not realize just how much they are putting at risk when they don’t accept what life presents them with, the questions and tasks that life sets them. When they resolve to spare themselves the pain and suffering, they owe a debt to their nature. In so doing, they refuse to pay life’s dues and for this very reason, life then often leads them astray. If we don’t accept our own destiny, a different kind of suffering takes its place… One cannot do more than live what one really is. And we are all made up of opposites and conflicting tendencies. After much reflection, I have come to the conclusion that it is better to live what one really is and accept the difficulties that arise as a result — because avoidance is much worse.

Addie challenges the status quo and pushes the boundaries of freedom and in doing so, she gets more than she bargained for… or does she? In making her initial deal, is she avoiding her destiny or accepting it? It’s possible to come down on either side of the question. It wouldn’t surprise me if one of these days, Schwab writes a sequel that gives us a more definitive answer.

I’ll definitely be there for it… but the world is wide and there’s no limit to places you can set a book, so can we stay out of Brooklyn? Please? I’d give almost anything…

Abandon all hope, ye who enter here

Abandon all hope, ye who enter here

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Life Lessons from David Cronenberg

7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend

Here are 7 Author Shoutouts for this week. Find your favorite author or discover an…

The post 7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend appeared first on LitStack.

Book review: Someone you Can Build a Nest in by John Wiswell

Book links: Amazon, Goodreads

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Publisher: Length: Formats:

Someone You Can Build a Nest In is a monster romance. The main character, Shesheshen, is a shapeshifting creature able to build herself out of bones and organs of her victims. Yes, she eats people, but she is also trying to figure out love.

The story starts with Shesheshen getting chased out of her swamp by hunters and falling off a cliff. She’s rescued by Homily, a kind woman who has no idea that her new houseguest is actually the monster she’s been raised to hunt. Shesheshen is smitten with her, so obviously the next step is to kill Homily and lay eggs in her. Except that the more time they spend together, the more Shesheshen falls for her in ways that go beyond instinct of her kind.

Shesheshen’s point of view is funny, sometimes gross, and surprisingly thoughtful. She’s like an alien trying to understand humans, and her observations are hilarious. The tone reminded me The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, just with more body horror.

That said, the book does take some turns that didn’t land quite as well for me. There’s a big focus on Homily’s abusive family, and while I appreciate the book trying to handle serious themes, I wasn’t totally sold on how quickly and deeply Shesheshen understood things like trauma and emotional abuse.

Also, Homily never fully came alive for me as a character. She’s meant to be this warm, steady presence, but I found her kind of flat. Maybe that’s because we’re seeing her entirely through Shesheshen’s eyes, and Shesheshen spends so much time analyzing her rather than just letting us get to know her.

Even with those issues, I had a good time listening to this. It’s clever and has a surprisingly sweet heart under all the goo. It’s not a cozy romance or a full-on horror novel, but something in between. You kind of have to be in the right mood for it-but if the idea of a people-eating blob monster falling in love sounds fun to you, it’s definitely worth checking out.

Silverborn: The Mystery of Morrigan Crow (by Jessica Townsend)

(Book #4 in series. Suggest starting at Book #1 The Trials of Morrigan Crow)

Morrigan discovers she has family in the exclusive Silver District and finds herself whisked away from her home and living the life of the idle rich. But while attending a wedding the newly married groom is found murdered and she realises there is something very off in the Silver District.

As she investigates she learns things that will completely tear the Silver District apart.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

I hesitate. That which must not be spoken. I can’t help but think refugees of the Harry Potter series will enjoy the Nevermoor series. It’s a magical fantasy mystery series and while I’ve occasionally struggled with it, it is a lot of fun. This book did meander a little at first but it had a 5 Star ending.

Book Review: Eat the Ones You Love by Sarah Maria Griffin

I received a review copy from the publisher. This does not affect the contents of my review and all opinions are my own.

Eat the Ones You Love by Sarah Maria Griffin

Eat the Ones You Love by Sarah Maria Griffin

Mogsy’s Rating: 3 of 5 stars

Genre: Horror

Series: Stand Alone

Publisher: Tor Books (April 22, 2025)

Length: 288 pages

Author Information: Website | Twitter

Lately, I seem to be coming up on a lot of books that start strong, only to fizzle out halfway through and become something of a slog to finish. Eat the Ones You Love by Sarah Maria Griffin is the latest to fall into this category. While I still enjoyed myself, finishing this one took more effort than I expected, especially given its strong start and eerie premise.

As the story begins, we meet the protagonist Shell Pine who has found herself at a personal low point following a devastating job loss and a breakup with her long-time partner. Now she is back in her hometown, living with her parents. Desperate for work, she impulsively enters a flower shop in the rundown shopping mall nearby and asks about the HELP NEEDED sign in the window. Immediately, she senses a connection with the florist Neve, a young woman whose charismatic aura captures her attention. And just like that, Shell is invited back tomorrow morning to help open the shop and learn the ropes.

But suddenly, we are introduced to a new voice. For you see, Neve is harboring a terrible secret, one with deep ties to the history of the crumbling mall and its central terrarium where a strange, sentient entity resides. Not just a plant, it is also a predator, and Neve is more than its caregiver. Where its roots grow, it knows all. And it has seen Shell, the way she is drawn to Neve, and now it wants her too.

My summary might be vague, but anything more I really don’t want to give away because most of my enjoyment came from unraveling the rest of the story’s mysteries. Eat the Ones You Love is a horror novel, but it is also an unconventional one in that most of its genre elements are more suggestive than shocking, edging ever so slightly into body horror but primarily dealing with psychological dread. And how can you not love an antagonist that is a homicidal sentient plant? A fascinating creation driven by unrelenting hunger, it also has an unhealthy obsession with Neve, who calls it her “baby.” But of course, of all the POVs in this book, the plant’s had to be my favorite, not only because it was so unique but also because of how convinced I was of its danger and menace.

That said, as I alluded to above, the book does lose some of its bite in the middle. As Shell settles into her new job and becomes accepted into a social group made up of other workers at the mall, the overall plot’s movement stalls to explore these friendships. Pretty soon, the focus is shifting to day-to-day workplace shenanigans and interpersonal drama and mall politics. Maybe the author’s original intent was to add depth to the world and build up the layers of context around the characters, but after a while, it just felt like a lot of filler to me. More than once, I found myself wishing we could get back to the horror story. In the end, learning about who’s sleeping with whom was simply not as interesting as the only relationship that mattered to me—the one between Neve and her parasitic plant baby.

Ultimately, Eat the Ones You Love is an ambitious novel, and unapologetically weird in all the right ways without being too over-the-top to stay in my wheelhouse. I’ve long thought killer plants and the horror genre go hand-in-hand, and Sarah Maria Griffin taps into that rich tradition with flair and originality. Beyond that, the story also weaves together various themes that feel like a perfect fit, like the bleakness of messy relationships and dying shopping malls.

But I have to say, the book’s biggest shortcoming lies in its lack of story balance leading to uneven pacing. Human drama often got in the way of the author’s painstakingly crafted horror narrative, diluting the creepy tension built through the unsettling voice of the plant creature. To be honest, I could have used a bit more suspense, a little more of that fear factor. That said, for fans of slow-burn horror and character-driven stories grounded by a rich and offbeat premise, it’s probably worth a look.

![]()

![]()

Houses of Ill Repute: Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix and Starling House by Alix E. Harrow

Witchcraft for Wayward Girls by Grady Hendrix (Berkley, January 14, 2025) and

Starling House by Alix E. Harrow (Tor Books, October 3, 2023). Covers: uncredited, Micaela Alcaino

No, not that kind of house of ill repute (though I confess I thought the semi-salacious implication of the headline might get some of you to read a bit further, though of course not you who are reading this now, just all those others). Rather the gothic trope of the creepy house, the mansion where ancestral secrets lie, where bad things happen. From The House of Seven Gables to The Fall of the House of Usher to Wuthering Heights to more contemporary (all the more so because they actually existed) houses of horror such as Colson Whitehead’s Nickel Academy and Tananarive Due’s Dozier School of Boys, these are places that present a facade of safety, but are far from it.

That’s the kind of house found in Grady Hendrix’s Witchcraft for Wayward Girls. Don’t be put off by the middle school YA sounding title. Homes for “wayward girls” actually existed in mid-20th century Florida. It was where unmarried pregnant teenagers were sent to have their babies, give them up for adoption, and then return to “normal” life with their and their family’s “reputations” intact.

The adolescent pregnant girls, literally abandoned by her parents for committing a sexual and “moral” offense (to my knowledge, there were no homes for boys who fathered out-of-wedlock babies and put the mothers in this position) became subject to “we know what’s best for you” treatment and holier-than-thou attitudes. In all too many cases, preserving the girl’s good name and future marriageability provided cover for the lucrative practice of selling newborns to adoptive parents on top of charging parents for room and board and, above all, discretion.

As Hendrix points out in an afterword,

Most homes confined their girls to the property… [some] forbade the use of makeup, censored the girls’ mail, charged them extra for dessert, and refused to allow them any communication with the outside world…Girls who changed their minds about adoption and tried to keep their babies would be subject to a tactic a tactic informally known as “The Bill.” At the last minute, a caseworker or staff member would inform the girl that her accumulated charges had to be paid before she could go home with their child. The Bill was usually so high that a girl had no hope of paying and so, whether she wanted to or not, she had to allow her baby to be put up for adoption.

This kind of house already earns its horrific bona fides without need of supernatural intervention (indeed, Hendrix says the first two drafts didn’t contain any fantastical elements). Adding witchcraft, however, layers a metaphor for women’s empowerment, albeit one that carries a price, that is closely associated in folklore with childbirth. As Hendrix notes,

There’s a popular [though discredited] myth that the Catholic Church targeted midwives as witches… In fairy tales, witches are constantly eating or stealing babies. In the fevered popular imagination, witches crown their black sabbaths with a child sacrifice.

The story centers on Fern (all the girls are given an arbitrary plant-based pseudonym during their stays, ostensibly to preserve privacy, but actually to depersonalize them), a 15 year old in effect kidnapped by her father to endure her pregnancy at the Wellwood House in St. Augustine, Florida in the summer of 1970. Her situation is not, needless to say, a happy one.

No one would write, no one would call, no one outside this house even knew where she was, except her dad, and he hated her. She never felt more alone. She would do whatever they wanted her to say, eat whatever they told he to ear, just so long as they let her of back to the way thing were before.

The smart-assed (if ultimately superficial) hippie-styled resistance of a fellow wayward girl provides some hope of eventual escape from the home’s adult “benefactors.” But it is a bookmobile librarian who hands Fern a tome entitled How to be a Groovy Witch that leads to the invocation of witchcraft to avenge mistreatment.

Unfortunately, to paraphrase Peter Parker, with great power comes unexpected consequences and questions of responsibility. And just as it’s one thing to proclaim hippie slogans and quite another to actually adhere to them in the real world, practicing witchcraft also comes with significant moral compromises. Which Fern must balance against the familial and social stigma of unwed pregnancy, of being forced to give birth and then relinquish her child. As once of the wayward girls now an adult and long after giving up her baby puts it:

There’s a part of me that’ll always be seventeen. A part of me that’ll be seventeen forever, locked away in that Home, cut off from the world.

That’s a house you can run away from, but never escape.

Locked away and cut off from the world is also the predicament in Alix E. Harrow’s The Starling House. Instead of the proverbial madwoman in the attic, it’s a male recluse in the titular creepy home containing disturbing secrets. Another kind of forced habitation is the stifling town, the ironically named Eden, Kentucky, modeled somewhat after the equally ironically named and actual Paradise, Kentucky immortalized in the John Prine song about a family-owned coal company that exploits the land and resident workers. It’s a place Kentucky native Harrow knows as “a place of very mixed experiences that I love very, very, very much, and which has just an incredible violence and terror to it.”

Our heroine, Opal, is a social malcontent and for the most part first-person narrator (there are also point of view shifts and even footnotes and a bibliography!), a high school dropout working a dead-end job in a dead end town. Orphaned following her mother’s death in a car crash, she is trying to save up money to send younger brother Jasper to a private school and get a better life out of Eden. But kind of hard to do on a Tractor Supply cashier’s salary and some petty larceny.

Walking to work, Opal finds herself strangely (of course) drawn to the ancestral home of the Starling family, one of whom wrote a dark fantasy for children called The Underland (the book’s illustrations appear throughout) and disappeared under, of course, mysterious circumstances. Part of the house’s appeal to Opal is how the shapes on the front gate remind her of the creatures depicted in The Underland.

The gates of Starling House don’t look like much from a distance — just a dense tangle of metal half-eaten by rust and ivy, held shut by a padlock so large it almost feels rude — but up close you can make out individual shapes: clawed feet and legs with too many joints, scaled backs and mouths full of teeth, heads with empty holes for eyes.

Opal feels compelled to look inside the old neglected house, managing to convince the current Warden, Arthur Starling, despite his initial misgivings, to hire her as a housekeeper. Opal soon discovers a special strange connection to the equally strange house. And to Arthur.

Sinister forces soon intercede, however. The aptly named Gravely Power company wants to acquire the Starling House property by means fair or foul. And then there are supernatural entities literally right out of The Underling. All of which jeopardize Opal’s already problematic relationship with Arthur.

The Starling House has rooms for just about everything — Southern gothic horror, classic fairy tale, corporate evil, environmental and class issues, a love story even (it’s not coincidental that Harrow makes a point of mentioning in the Acknowledgement that her mother “read every version of Beauty and the Beast with me”), all wrapped together in a single, ahem, attractive property. It’ll particularly resonate with anyone who grew up in a small town or boring subdivision who tried to run away from the horror of humdrum existence.

David Soyka is one of the founding bloggers at Black Gate. He’s written over 200 articles for us since 2008. His most recent was a review of The Bright Sword by Lev Grossman.

Dishhhwashhher

My dearest BDH,

I come to this keyboard today to write to you that we are well. It has been 8 days without a working dishwasher. It is but by the grace of the higher power that we are surviving this crisis. Hope alone sustains us through these dark times, hope that a new dishwasher shall arrive today between the hours of 01:00 PM and 05:00 PM from Wilson Appliances.

Forever yours and deep in dishes,

Ilona, Your Loving Author.

The trouble with the dishwasher started as soon as we came back from vacation. After we got home, I marinated some chicken, and ended up with a load of dishes that had a big glass marinading dish in it.

I start the dishwasher. It gets through part of the cycle. I come back to the kitchen.

DRAIN.

Okay. I have done this song and dance before. I open the dishwasher full of nasty chicken water. Ugh. I get gloves, scoop the water out, take out the filter, clean it out – it’s clean, put it back in, hit the rinse and hold cycle.

DRAIN.

Grrr. I opened the dishwasher, scoop the nasty water out for the second time, remove filter, undo the plastic doohicky that protects a little fan. Sometimes stuff gets stuck under there, preventing the fan from rotating. The fan is clear. Nothing is stuck. Rinse and hold.

DRAIN.

*$##$%%^%$%^.

At that point it was late at night and I didn’t want to wrestle with the chicken water again, so I gave up.

Morning found Gordon messing with the dishwasher. He scooped the chicken water out, checked the filter, checked the fan.

DRAIN.

Maybe there was some grease accumulated somewhere and now things are clogged. We boil water, pour it into the dishwasher. The dishwasher drains. YES! Start the rinse and hold.

DRAIN.

More boiling water.

DRAIN.

DRAIN.

We hoped to have the dishwasher repaired, but nobody works on this brand. We did have a plumber out to check is the hose had clogged.

Plumber: It seems like the motor. How old is this dishwasher?

Gordon: 27 years.

Plumber: This might have something to do with your current problem.

So we bought a new dishwasher. In other news, I have finally finished the nobody knows how old bottle of Dawn’s dishwashing liquid that had been living alone in the dark under the sink.

The house is coming up on 30 years, and so far in the last 18 months the range quit, the fridge bit the dust, and now the dishwasher died.

::eyes the dual ovens::

Between you and me, if they die, I wouldn’t mind, because they are old and the temperature control is questionable. I’m pretty sure 375 is no longer 375. But we are keeping them until they die. They have got to hold on till the mid-fall at least. The Inheritance Buys New Ovens royalties should come in then.

Our smart thermostat quit, but we fixed it and Kid 1’s microwave gave up the ghost, so that concludes the trilogy of appliance breaking. These repairs usually come in threes, so let’s hope this cluster is behind us.

Here is hoping your appliances work well and last way past the manufacturer’s suggested lifecycle.

The post Dishhhwashhher first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Comment on A Beginner’s Guide to Drucraft #36: Essentia Capacity In Practice by Skeeve

Essentia capacity is a rate of converting ‘free’ essentia to personal and (with good skills) one can maximize the usage of sigils by skills and combining usage on and off.

Are there sigils that could influence the flow of essentia around someone (or some area) to make it harder for person to use their capacity to full extent?

18 Lectures in “Immemorial” Shine A Light | Making Memories For Our Future

Immemorial is a synthesis of reporting, memoir, and essay, reflecting on the design and function…

The post 18 Lectures in “Immemorial” Shine A Light | Making Memories For Our Future appeared first on LitStack.

Free Fiction Monday: Red Letter Day

Graduation Day at Barack Obama High School. The day the Red Letters arrive. The day that students get a glimpse into their own future.

But a handful never get a letter, and no one knows why. One teacher comes up with an idea though: a teacher who never got a Red Letter herself, a teacher finally finds the answers to her own fate.

Called “a fresh, solid, entertaining take on time travel” by Tangent Online, “Red Letter Day” was chosen as the best short story by the readers of Analog Magazine.

“Red Letter Day“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Red Letter Day By Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Graduation rehearsal—middle of the afternoon on the final Monday of the final week of school. The graduating seniors at Barack Obama High School gather in the gymnasium, get the wrapped packages with their robes (ordered long ago), their mortarboards, and their blue and white tassels. The tassels attract the most attention—everyone wants to know which side of the mortarboard to wear it on, and which side to move it to.

The future hovers, less than a week away, filled with possibilities.

Possibilities about to be limited, because it’s also Red Letter Day.

I stand on the platform, near the steps, not too far from the exit. I’m wearing my best business casual skirt today and a blouse that I no longer care about. I learned to wear something I didn’t like years ago; too many kids will cry on me by the end of the day, covering the blouse with slobber and makeup and aftershave.

My heart pounds. I’m a slender woman, although I’m told I’m formidable. Coaches need to be formidable. And while I still coach the basketball teams, I no longer teach gym classes because the folks in charge decided I’d be a better counselor than gym teacher. They made that decision on my first Red Letter Day at BOHS, more than twenty years ago.

I’m the only adult in this school who truly understands how horrible Red Letter Day can be. I think it’s cruel that Red Letter Day happens at all, but I think the cruelty gets compounded by the fact that it’s held in school.

Red Letter Day should be a holiday, so that kids are at home with their parents when the letters arrive.

Or don’t arrive, as the case may be.

And the problem is that we can’t even properly prepare for Red Letter Day. We can’t read the letters ahead of time: privacy laws prevent it.

So do the strict time travel rules. One contact—only one—through an emissary, who arrives shortly before rehearsal, stashes the envelopes in the practice binders, and then disappears again. The emissary carries actual letters from the future. The letters themselves are the old-fashioned paper kind, the kind people wrote 150 years ago, but write rarely now. Only the real letters, handwritten, on special paper get through. Real letters, so that the signatures can be verified, the paper guaranteed, the envelopes certified.

Apparently, even in the future, no one wants to make a mistake.

The binders have names written across them so the letter doesn’t go to the wrong person. And the letters are supposed to be deliberately vague.

I don’t deal with the kids who get letters. Others are here for that, some professional bullshitters—at least in my opinion. For a small fee, they’ll examine the writing, the signature, and try to clear up the letter’s deliberate vagueness, make a guess at the socio-economic status of the writer, the writer’s health, or mood.

I think that part of Red Letter Day makes it all a scam. But the schools go along with it, because the counselors (read: me) are busy with the kids who get no letter at all.

And we can’t predict whose letter won’t arrive. We don’t know until the kid stops mid-stride, opens the binder, and looks up with complete and utter shock.

Either there’s a red envelope inside or there’s nothing.

And we don’t even have time to check which binder is which.

***

I had my Red Letter Day thirty-two years ago, in the chapel of Sister Mary of Mercy High School in Shaker Heights, Ohio. Sister Mary of Mercy was a small co-ed Catholic High School, closed now, but very influential in its day. The best private school in Ohio according to some polls—controversial only because of its conservative politics and its willingness to indoctrinate its students.

I never noticed the indoctrination. I played basketball so well that I already had three full-ride scholarship offers from UCLA, UNLV, and Ohio State (home of the Buckeyes!). A pro scout promised I’d be a fifth round draft choice if only I went pro straight out of high school, but I wanted an education.

“You can get an education later,” he told me. “Any good school will let you in after you’ve made your money and had your fame.”

But I was brainy. I had studied athletes who went to the Bigs straight out of high school. Often they got injured, lost their contracts and their money, and never played again. Usually they had to take some crap job to pay for their college education—if, indeed, they went to college at all, which most of them never did.

Those who survived lost most of their earnings to managers, agents, and other hangers’ on. I knew what I didn’t know. I knew I was an ignorant kid with some great ball-handling ability. I knew that I was trusting and naïve and undereducated. And I knew that life extended well beyond thirty-five, when even the most gifted female athletes lost some of their edge.

I thought a lot about my future. I wondered about life past thirty-five. My future self, I knew, would write me a letter fifteen years after thirty-five. My future self, I believed, would tell me which path to follow, what decision to make.

I thought it all boiled down to college or the pros.

I had no idea there would be—there could be—anything else.

You see, anyone who wants to—anyone who feels so inclined—can write one single letter to their former self. The letter gets delivered just before high school graduation, when most teenagers are (theoretically) adults, but still under the protection of a school.

The recommendations on writing are that the letter should be inspiring. Or it should warn that former self away from a single person, a single event, or a one single choice.

Just one.

The statistics say that most folks don’t warn. They like their lives as lived. The folks motivated to write the letters wouldn’t change much, if anything.

It’s only those who’ve made a tragic mistake—one drunken night that led to a catastrophic accident, one bad decision that cost a best friend a life, one horrible sexual encounter that led to a lifetime of heartache—who write the explicit letter.

And the explicit letter leads to alternate universes. Lives veer off in all kinds of different paths. The adult who sends the letter hopes their former self will take their advice. If the former self does take the advice, then the kid who receives the letter from an adult they will never be. The kid, if smart, will become a different adult, the adult who somehow avoided that drunken night. That new adult will write a different letter to their former self, warning about another possibility or committing bland, vague prose about a glorious future.

There’re all kinds of scientific studies about this, all manner of debate about the consequences. All types of mandates, all sorts of rules.

And all of them lead back to that moment, that heart stopping moment that I experienced in the chapel of Sister Mary of Mercy High School, all those years ago.

We weren’t practicing graduation like the kids at Barack Obama High School. I don’t recall when we practiced graduation, although I’m sure we had a practice later in the week.

At Sister Mary of Mercy High School, we spent our Red Letter Day in prayer. All the students started their school days with Mass. But on Red Letter Day, the graduating seniors had to stay for a special service, marked by requests for God’s forgiveness and exhortations about the unnaturalness of what the law required Sister Mary of Mercy to do.

Sister Mary of Mercy High School loathed Red Letter Day. In fact, Sister Mary of Mercy High School, as an offshoot of the Catholic Church, opposed time travel altogether. Back in the dark ages (in other words, decades before I was born), the Catholic Church declared time travel an abomination, antithetical to God’s will.

You know the arguments: If God had wanted us to travel through time, the devout claim, he would have given us the ability to do so. If God had wanted us to travel through time, the scientists say, he would have given us the ability to understand time travel—and oh! Look! He’s done that.

Even now, the arguments devolve from there.

But time travel has become a fact of life for the rich and the powerful and the well-connected. The creation of alternate universes scares them less than the rest of us, I guess. Or maybe the rich really don’t care—they being different from you and I, as renowned (but little read) 20th Century American author F. Scott Fitzgerald so famously said.

The rest of us—the non-different ones—realized nearly a century ago that time travel for all was a dicey proposition, but this being America, we couldn’t deny people the opportunity of time travel.

Eventually time travel for everyone became a rallying cry. The liberals wanted government to fund it, and the conservatives felt only those who could afford it would be allowed to have it.

Then something bad happened—something not quite expunged from the history books, but something not taught in schools either (or at least the schools I went to), and the federal government came up with a compromise.

Everyone would get one free opportunity for time travel—not that they could actually go back and see the crucifixion or the Battle of Gettysburg—but that they could travel back in their own lives.

The possibility for massive change was so great, however, that the time travel had to be strictly controlled. All the regulations in the world wouldn’t stop someone who stood in Freedom Hall in July of 1776 from telling the Founding Fathers what they had wrought.

So the compromise got narrower and narrower (with the subtext being that the masses couldn’t be trusted with something as powerful as the ability to travel through time), and it finally became Red Letter Day, with all its rules and regulations. You’d have the ability to touch your own life without ever really leaving it. You’d reach back into your own past and reassure yourself, or put something right.

Which still seemed unnatural to the Catholics, the Southern Baptists, the Libertarians, and the Stuck in Time League (always my favorite, because they never did seem to understand the irony of their own name). For years after the law passed, places like Sister Mary of Mercy High School tried not to comply with it. They protested. They sued. They got sued.

Eventually, when the dust settled, they still had to comply.

But they didn’t have to like it.

So they tortured all of us, the poor hopeful graduating seniors, awaiting our future, awaiting our letters, awaiting our fate.

I remember the prayers. I remember kneeling for what seemed like hours. I remember the humidity of that late spring day, and the growing heat, because the chapel (a historical building) wasn’t allowed to have anything as unnatural as air conditioning.

Martha Sue Groening passed out, followed by Warren Iverson, the star quarterback. I spent much of that morning with my forehead braced against the pew in front of me, my stomach in knots.

My whole life, I had waited for this moment.

And then, finally, it came. We went alphabetically, which stuck me in the middle, like usual. I hated being in the middle. I was tall, geeky, uncoordinated, except on the basketball court, and not very developed—important in high school. And I wasn’t formidable yet.

That came later.

Nope. Just a tall awkward girl, walking behind boys shorter than I was. Trying to be inconspicuous.

I got to the aisle, watching as my friends stepped in front of the altar, below the stairs where we knelt when we went up for the sacrament of communion.

Father Broussard handed out the binders. He was tall but not as tall as me. He was tending to fat, with most of it around his middle. He held the binders by the corner, as if the binders themselves were cursed, and he said a blessing over each and every one of us as we reached out for our futures.

We weren’t supposed to say anything, but a few of the boys muttered, “Sweet!” and some of the girls clutched their binders to their chests as if they’d received a love letter.

I got mine—cool and plastic against my fingers—and held it tightly. I didn’t open it, not near the stairs, because I knew the kids who hadn’t gotten theirs yet would watch me.

So I walked all the way to the doors, stepped into the hallway, and leaned against the wall.

Then I opened my binder.

And saw nothing.

My breath caught.

I peered back into the chapel. The rest of the kids were still in line, getting their binders. No red envelopes had landed on the carpet. No binders were tossed aside.

Nothing. I stopped three of the kids, asking them if they saw me drop anything or if they’d gotten mine.

Then Sister Mary Catherine caught my arm, and dragged me away from the steps. Her fingers pinched into the nerve above my elbow, sending a shooting pain down to my hand.

“You’re not to interrupt the others,” she said.

“But I must have dropped my letter.”

She peered at me, then let go of my arm. A look of satisfaction crossed her fat face, then she patted my cheek.

The pat was surprisingly tender.

“Then you are blessed,” she said.

I didn’t feel blessed. I was about to tell her that, when she motioned Father Broussard over.

“She received no letter,” Sister Mary Catherine said.

“God has smiled on you, my child,” he said warmly. He hadn’t noticed me before, but this time, he put his hand on my shoulder. “You must come with me to discuss your future.”

I let him lead me to his office. The other nuns—the ones without a class that hour—gathered with him. They talked to me about how God wanted me to make my own choices, how He had blessed me by giving me back my future, how He saw me as without sin.

I was shaking. I had looked forward to this day all my life—at least the life I could remember—and then this. Nothing. No future. No answers.

Nothing.

I wanted to cry, but not in front of Father Broussard. He had already segued into a discussion of the meaning of the blessing. I could serve the church. Anyone who failed to get a letter got free admission into a variety of colleges and universities, all Catholic, some well known. If I wanted to become a nun, he was certain the church could accommodate me.

“I want to play basketball, Father,” I said.

He nodded. “You can do that at any of these schools.”

“Professional basketball,” I said.

And he looked at me as if I were the spawn of Satan.

“But, my child,” he said with a less reasonable tone than before, “you have received a sign from God. He thinks you Blessed. He wants you in his service.”

“I don’t think so,” I said, my voice thick with unshed tears. “I think you made a mistake.”

Then I flounced out of his office, and off school grounds.

My mother made me go back for the last four days of class. She made me graduate. She said I would regret it if I didn’t.

I remember that much.

But the rest of the summer was a blur. I mourned my known future, worried I would make the wrong choices, and actually considered the Catholic colleges. My mother rousted me enough to get me to choose before the draft. And I did.

The University of Nevada in Las Vegas, as far from the Catholic Church as I could get.

I took my full ride, and destroyed my knee in my very first game. God’s punishment, Father Broussard said when I came home for Thanksgiving.

And God forgive me, I actually believed him.

But I didn’t transfer—and I didn’t become Job, either. I didn’t fight with God or curse God. I abandoned Him because, as I saw it, He had abandoned me.

***

Thirty-two years later, I watch the faces. Some flush. Some look terrified. Some burst into tears.

But some just look blank, as if they’ve received a great shock.

Those students are mine.

I make them stand beside me, even before I ask them what they got in their binder. I haven’t made a mistake yet, not even last year, when I didn’t pull anyone aside.

Last year, everyone got a letter. That happens every five years or so. All the students get Red Letters, and I don’t have to deal with anything.

This year, I have three. Not the most ever. The most ever was thirty, and within five years it became clear why. A stupid little war in a stupid little country no one had ever heard of. Twenty-nine of my students died within the decade. Twenty-nine.

The thirtieth was like me, someone who has not a clue why her future self failed to write her a letter.

I think about that, as I always do on Red Letter Day.

I’m the kind of person who would write a letter. I have always been that person. I believe in communication, even vague communication. I know how important it is to open that binder and see that bright red envelope.

I would never abandon my past self.

I’ve already composed drafts of my letter. In two weeks—on my fiftieth birthday—some government employee will show up at my house to set up an appointment to watch me write the letter.

I won’t be able to touch the paper, the red envelope or the special pen until I agree to be watched. When I finish, the employee will fold the letter, tuck it in the envelope and earmark it for Sister Mary of Mercy High School in Shaker Heights, Ohio, thirty-two years ago.

I have plans. I know what I’ll say.

But I still wonder why I didn’t say it to my previous self. What went wrong? What prevented me? Am I in an alternate universe already and I just don’t know it?

Of course, I’ll never be able to find out.

But I set that thought aside. The fact that I did not receive a letter means nothing. It doesn’t mean that I’m blessed by God any more than it means I’ll fail to live to fifty.

It is a trick, a legal sleight of hand, so that people like me can’t travel to the historical bright spots or even visit the highlights of their own past life.

I continue to watch faces, all the way to the bitter end. But I get no more than three. Two boys and a girl.

Carla Nelson. A tall, thin, white-haired blonde who ran cross-country and stayed away from basketball, no matter how much I begged her to join the team. We needed height and we needed athletic ability.

She has both, but she told me, she isn’t a team player. She wanted to run and run alone. She hated relying on anyone else.

Not that I blame her.

But from the devastation on her angular face, I can see that she relied on her future self. She believed she wouldn’t let herself down.

Not ever.

Over the years, I’ve watched other counselors use platitudes. I’m sure it’s nothing. Perhaps your future self felt that you’re on the right track. I’m sure you’ll be fine.

I was bitter the first time I watched the high school kids go through this ritual. I never said a word, which was probably a smart decision on my part, because I silently twisted my colleagues’ platitudes into something negative, something awful, inside my own head.

It’s something. We all know it’s something. Your future self hates you or maybe—probably—you’re dead.

I have thought all those things over the years, depending on my life. Through a checkered college career, an education degree, a marriage, two children, a divorce, one brand new grandchild. I have believed all kinds of different things.

At thirty-five, when my hopeful young self thought I’d be retiring from pro ball, I stopped being a gym teacher and became a full time counselor. A full time counselor and occasional coach.

I told myself I didn’t mind.

I even wondered what would I write if I had the chance to play in the Bigs? Stay the course? That seems to be the most common letter in those red envelopes. It might be longer than that, but it always boils down to those three words.

Stay the course.

Only I hated the course. I wonder: would I have blown my knee out in the Bigs? Would I have made the Bigs? Would I have received the kind of expensive nanosurgery that would have kept my career alive? Or would I have washed out worse than I ever had?

Dreams are tricky things.

Tricky and delicate and easily destroyed.

And now I faced three shattered dreamers, standing beside me on the edge of the podium.

“To my office,” I say to the three of them.

They’re so shell-shocked that they comply.

I try to remember what I know about the boys. Esteban Rellier and J.J. Feniman. J.J. stands for…Jason Jacob. I remembered only because the names were so very old-fashioned, and J.J. was the epitome of modern cool.

If you had to choose which students would succeed based on personality and charm, not on Red Letters and opportunity, you would choose J.J.

You would choose Esteban with a caveat. He would have to apply himself.

If you had to pick anyone in class who wouldn’t write a letter to herself, you would pick Carla. Too much of a loner. Too prickly. Too difficult. I shouldn’t have been surprised that she’s coming with me.

But I am.

Because it’s never the ones you suspect who fail to get a letter.

It’s always the ones you believe in, the ones you have hopes for.

And somehow—now—it’s my job to keep those hopes alive.

***

I am prepared for this moment. I’m not a fan of interactive technology—feeds scrolling across the eye, scans on the palm of the hand—but I use it on Red Letter Day more than any other time during the year.

As we walk down the wide hallway to the administrative offices, I learn everything the school knows about all three students which, honestly, isn’t much.

Psych evaluations—including modified IQ tests—from grade school on. Addresses. Parental income and employment. Extracurriculars. Grades. Troubles (if any reported). Detentions. Citations. Awards.

I already know a lot about J.J. already. Homecoming king, quarterback, would’ve been class president if he hadn’t turned the role down. So handsome he even has his own stalker, a girl named Lizbet Cholene, whom I’ve had to discipline twice before sending to a special psych unit for evaluation.

I have to check on Esteban. He’s above average, but only in the subjects that interest him. His IQ tested high on both the old exam and the new. He has unrealized potential, and has never really been challenged, partly because he doesn’t seem to be the academic type.

It’s Carla who is still the enigma. IQ higher than either boy’s. Grades lower. No detentions, citations, or academic awards. Only the postings in cross country—continual wins, all state three years in a row, potential offers from colleges, if she brought her grades up, which she never did. Nothing on the parents. Address in a middle-class neighborhood, smack in the center of town.

I cannot figure her out in a three-minute walk, even though I try.

I usher them into my office. It’s large and comfortable. Big desk, upholstered chairs, real plants, and a view of the track—which probably isn’t the best thing right now, at least for Carla.

I have a speech that I give. I try not to make it sound canned.

“Your binders were empty, weren’t they?” I say.

To my surprise, Carla’s lower lip quivers. I thought she’d tough it out, but the tears are close to the surface. Esteban’s nose turns red and he bows his head. Carla’s distress makes it hard for him to control his.

J.J. leans against the wall, arms folded. His handsome face is a mask. I realize then how often I’d seen that look on his face. Not quite blank—a little pleasant—but detached, far away. He braces one foot on the wall, which is going to leave a mark, but I don’t call him on that. I just let him lean.

“On my Red Letter Day,” I say, “I didn’t get a letter either.”

They look at me in surprise. Adults aren’t supposed to discuss their letters with kids. Or their lack of letters. Even if I had been able to discuss it, I wouldn’t have.

I’ve learned over the years that this moment is the crucial one, the moment when they realize that you will survive the lack of a letter.

“Do you know why?” Carla asks, her voice raspy.

I shake my head. “Believe me, I’ve wondered. I’ve made up every scenario in my head—maybe I died before it was time to write the letter—”

“But you’re older than that now, right?” J.J. asks, with something of an angry edge. “You wrote the letter this time, right?”

“I’m eligible to write the letter in two weeks,” I say. “I plan to do it.”

His cheeks redden, and for the first time, I see how vulnerable he is beneath the surface. He’s as devastated—maybe more devastated—than Carla and Esteban. Like me, J.J. believed he would get the letter he deserved—something that told him about his wonderful, successful, very rich life.

“So you could still die before you write it,” he said, and this time, I’m certain he meant the comment to hurt.

It did. But I don’t let that emotion show on my face. “I could,” I say. “But I’ve lived for thirty-two years without a letter. Thirty-two years without a clue about what my future holds. Like people used to live before time travel. Before Red Letter Day.”

I have their attention now.

“I think we’re the lucky ones,” I say, and because I’ve established that I’m part of their group, I don’t sound patronizing. I’ve given this speech for nearly two decades, and previous students have told me that this part of the speech is the most important part.

Carla’s gaze meets mine, sad, frightened and hopeful. Esteban keeps his head down. J.J.’s eyes have narrowed. I can feel his anger now, as if it’s my fault that he didn’t get a letter.

“Lucky?” he asks in the same tone that he used when he reminded me I could still die.

“Lucky,” I say. “We’re not locked into a future.”

Esteban looks up now, a frown creasing his forehead.

“Out in the gym,” I say, “some of the counselors are dealing with students who’re getting two different kinds of tough letters. The first tough one is the one that warns you not to do something on such and so date or you’ll screw up your life forever.”

“People actually get those?” Esteban asks, breathlessly.

“Every year,” I say.

“What’s the other tough letter?” Carla’s voice trembles. She speaks so softly I had to strain to hear her.

“The one that says You can do better than I did, but won’t—can’t really—explain exactly what went wrong. We’re limited to one event, and if what went wrong was a cascading series of bad choices, we can’t explain that. We just have to hope that our past selves—you guys, in other words—will make the right choices, with a warning.”

J.J.’s frowning too. “What do you mean?”

“Imagine,” I say, “instead of getting no letter, you get a letter that tells you that none of your dreams come true. The letter tells you simply that you’ll have to accept what’s coming because there’s no changing it.”

“I wouldn’t believe it,” he says.

And I agree: he wouldn’t believe it. Not at first. But those wormy little bits of doubt would burrow in and affect every single thing he does from this moment on.

“Really?” I say. “Are you the kind of person who would lie to yourself in an attempt to destroy who you are now? Trying to destroy every bit of hope that you possess?”

His flush grows deeper. Of course he isn’t. He lies to himself—we all do—but he lies to himself about how great he is, how few flaws he has. When Lizbet started following him around, I brought him into my office and asked him not to pay attention to her.

It leads her on, I say.

I don’t think it does, he says. She knows I’m not interested.

He knew he wasn’t interested. Poor Lizbet had no idea at all.

I can see her outside now, hovering in the hallway, waiting for him, wanting to know what his letter said. She’s holding her red envelope in one hand, the other lost in the pocket of her baggy skirt. She looks prettier than usual, as if she’s dressed up for this day, maybe for the inevitable party.

Every year, some idiot plans a Red Letter Day party even though the school—the culture—recommends against it. Every year, the kids who get good letters go. And the other kids beg off, or go for a short time, and lie about what they received.

Lizbet probably wants to know if he’s going to go.

I wonder what he’ll say to her.

“Maybe you wouldn’t send a letter if the truth hurt too much,” Esteban says.

And so it begins, the doubts, the fears.

“Or,” I say, “if your successes are beyond your wild imaginings. Why let yourself expect that? Everything you do might freeze you, might lead you to wonder if you’re going to screw that up.”

They’re all looking at me again.

“Believe me,” I say. “I’ve thought of every single possibility, and they’re all wrong.”

The door to my office opens and I curse silently. I want them to concentrate on what I just said, not on someone barging in on us.

I turn.

Lizbet has come in. She looks like she’s on edge, but then she’s always on edge around J.J.

“I want to talk to you, J.J.” Her voice shakes.

“Not now,” he says. “In a minute.”

“Now,” she says. I’ve never heard this tone from her. Strong and scary at the same time.

“Lizbet,” J.J. says, and it’s clear he’s tired, he’s overwhelmed, he’s had enough of this day, this event, this girl, this school—he’s not built to cope with something he considers a failure. “I’m busy.”

“You’re not going to marry me,” she says.

“Of course not,” he snaps—and that’s when I know it. Why all four of us don’t get letters, why I didn’t get a letter, even though I’m two weeks shy from my fiftieth birthday and fully intend to send something to my poor past self.

Lizbet holds her envelope in one hand, and a small plastic automatic in the other. An illegal gun, one that no one should be able to get—not a student, not an adult. No one.

“Get down!” I shout as I launch myself toward Lizbet.

She’s already firing, but not at me. At J.J. who hasn’t gotten down.

But Esteban deliberately drops and Carla—Carla’s half a step behind me, launching herself as well.

Together we tackle Lizbet, and I pry the pistol from her hands. Carla and I hold her as people come running from all directions, some adults, some kids holding letters.

Everyone gathers. We have no handcuffs, but someone finds rope. Someone else has contacted emergency services, using the emergency link that we all have, that we all should have used, that I should have used, that I probably had used in another life, in another universe, one in which I didn’t write a letter. I probably contacted emergency services and said something placating to Lizbet, and she probably shot all four of us, instead of poor J.J.