Feed aggregator

On McPig's Wishliat - Confessions From the Group Chat

Confessions From the Group Chatby Jodi Meadows

Confessions From the Group Chatby Jodi MeadowsWhat happens in the group chat stays in the group chat… until it doesn’t.

Virginia Vaughn just wants to fit in with her super-popular friend group. That means she doesn’t let them know how much she loves the library, she never speaks a word about her massive crush on tragically unpopular Grayson, and she says nasty things she doesn’t actually mean. But only in the group chat, so it’s harmless, right?

But when she has a blowout fight with her clique—specifically, with the Queen Bee herself—her mean texts are posted online for the entire school to see! And, suddenly, Virginia has no one but her cat to talk to.

Cue "Knight Errant," a mystery boy at school who texts Virginia by accident—and who quickly becomes her closest confidante. Though they send messages back and forth for hours every night, Virginia doesn’t want him to know which classmate she is (because then he’ll connect her to the mean texts ALL OVER THE INTERNET). She likes him, but she really likes Grayson, too. Can she find the strength to tell Knight who she really is? And will Grayson—who has become her only ally at school—give up on her when the awful things she’s said about him are finally posted?

Confessions from the Group Chat is the second middle-grade romcom from New York Times bestselling author Jodi Meadow (BYE FOREVER, I GUESS; MY LADY JANE, now streaming on Prime). Sweet, funny, and authentically messy, this is an ultra-cute story about middle-school misbehavior, innocent first love, and the inner life of a repentant mean girl.

Expected publication October 21, 2025

Review: The Gentleman and his Vowsmith by Rebecca Ide

Buy The Gentleman and His VowsmithFORMAT/INFO: The Gentleman and His Vowsmith releases on April 15th, 2024 from Saga Press Books. It is 464 pages long and available in paperback, ebook, and audiobook formats.

OVERVIEW/ANALYSIS: To save his crumbling family estate, playboy Lord Nicholas Monterris has finally agreed to take a wife. As is tradition, that means the families of the bride and groom will be magically locked into the Monterris family manor while the magical marriage contract is negotiated and signed. To make a bad situation worse, the vowsmith for the bride's family is none other than Dashiell sa Vare, an old flame of Nicholas's who ended their relationship years ago suddenly and without warning. But all past feuds have to be set aside when people start turning up dead. Someone doesn't want this marriage to go through and they're willing to kill to make it happen. Nicholas, Dashiell, and bride-to-be Leaf have to work together to find the murderer before they end up the next victim.

The Gentleman and His Vowsmith is a well-mixed blend of Regency murder mystery and queer romantasy. It takes two rival noble families and their underlings, traps them in an isolated manor house, and mixes in a little murder and a dash of ghostly apparitions. The result is a pot bubbling over with emotions, ranging from love to resentment. In the forced proximity, people are forced to confront their unspoken affections and hash out long simmering hatred. All of this is underpinned by the overall gothic tone, the dark hallways and eerie sights that leave the guests wondering if the murderer is human...or something else.

And with all this talk of passion, now is the time to mention that this is definitely a spicy romantasy. If you're not a fan of explicit scenes, don't pick this one up. Things get hot and heavy between our leads in short order, and it carries on throughout the book. Honestly, as much as I enjoyed the catharsis of two pining lovers finally satiating themselves, at a certain point I was wishing they would keep their hands off each other for five minutes so we could get back to the murder solving.

(I also want to mention that if you're concerned that the bride in this situation gets the short end of the stick, don't worry. This isn't a situation where she's being cheated on or otherwise getting left out in the cold. She's being forced into the marriage as much as Nicholas and for various reasons is perfectly fine with him wanting to be with someone else.)

I did enjoy the queer reimagining of the Regency era, with same sex pairings fully accepted. This doesn't mean Regency society is suddenly perfect. Social stratification still exists (a noble cannot simply marry a "lowly" vowsmith") and you're still expected to carry on the family name through marriage (even if it requires something like a "stud" clause for those who don't want to sexually partner with their spouse). Nobody blinks an eye, however, at the idea of same sex relationships, as long as all the other social norms are being followed.

Overall the mystery itself is a solid twisty affair, with plenty of clues and red herrings to keep the reader on their toes. There's lots of family drama to unpack, with each new revelation providing another motive for murder. I admit, I was slightly underwhelmed by the eventual reveal of the murderer at the end of the day (given the range of options I had considered), but the journey to get to that point was satisfying.

CONCLUSION: In short, do you like murder mysteries? Do you like romantasy? If you answered yes to both questions, then do yourself a favor and pick up The Gentleman and his Vowsmith

The Inheritance Begins

April 18, 2025

We are at war.

This war is not about wealth, resources, or a difference of ideology. It’s a war of survival. The very existence of humanity is at stake.

The moment the first gate burst, sending a monster horde to rage through our world, it brought us unimaginable suffering, but it also awoke something slumbering deep within some of us, a means to repel and destroy our enemy. Powers beyond comprehension. Abilities that are legendary.

The war is ongoing. If you are a Talent, your country needs you. The world needs you. Be the hero you always wanted to be.

Take my hand and answer the call.

Elias McFeron

Guildmaster of Cold Chaos

The post The Inheritance Begins first appeared on ILONA ANDREWS.

Women in SF&F Month: Lucia Damisa

Today’s Women in SF&F Month guest is Lucia Damisa! She is the coordinator of Path2pub (Path To Publication), a website where writers offer tips and advice while sharing about their journeys and experiences. Her first novel, A Desert of Bleeding Sand, was just released with Darkan Press at the end of March, and it will be joined by A Winter of White Ash, the second book in her five-book series, this summer. Inspired in part by Nigerian and other African mythology, […]

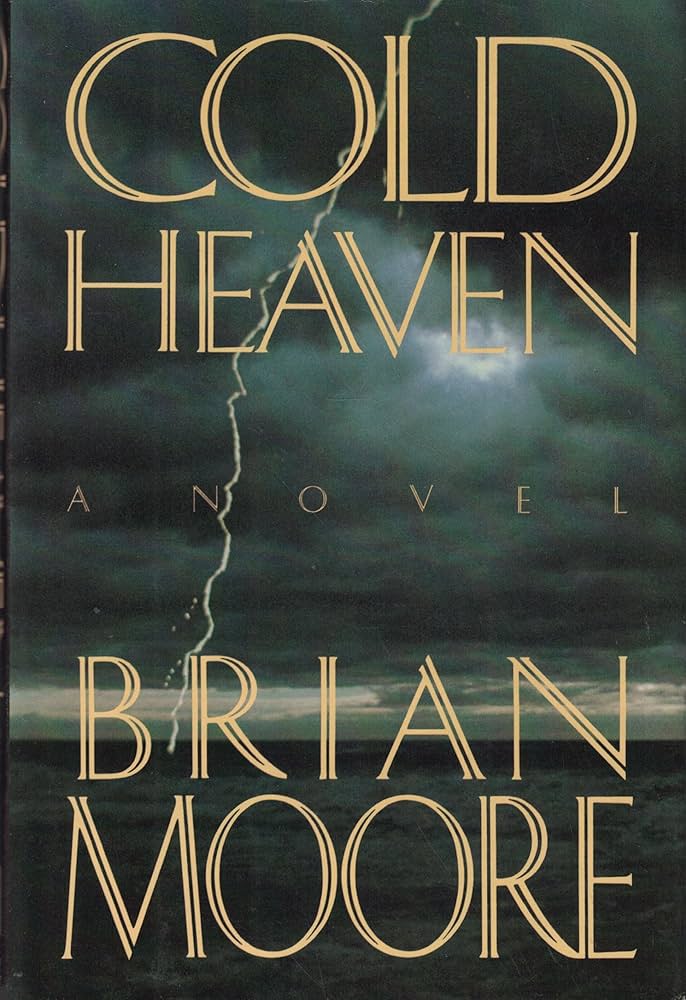

The post Women in SF&F Month: Lucia Damisa first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.A Metaphysical Nightmare: Brian Moore’s Cold Heaven

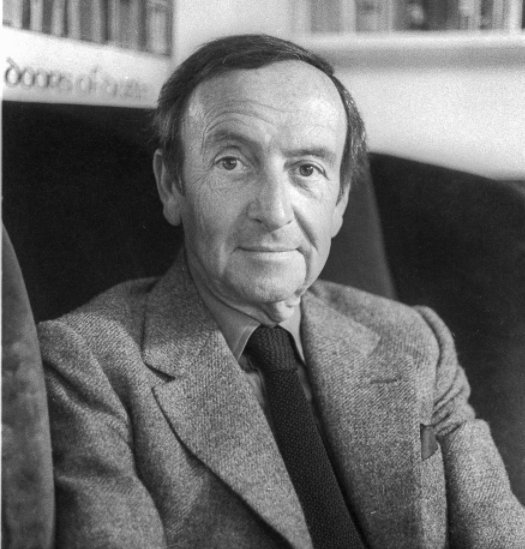

The Irish writer Brian Moore, who died in 1999 (he pronounced his first name in the Irish fashion — Bree-an) was one of the most interesting novelists of his time, at least based on the four books of his that I’ve read, all of which deal with areas where the supernatural, the philosophical, and the theological intersect and blur into each other.

Catholics (1972) is set in the near future after a hypothetical Fourth Vatican Council has banned private confession, clerical garb, and the Latin mass, while the fictitious Pope of the novel is engaged in negotiating a formal merger of Roman Catholicism and Buddhism, radical changes that are resisted by a handful of monks living on a small island off the coast of Ireland. In The Great Victorian Collection (1975), a scholar dreams of a fabulous collection of Victorian artifacts, and when he wakes up, it has actually appeared in the parking lot outside his California motel room. Who will believe such a thing? Can he believe it himself? Black Robe (1985) is a painstakingly detailed — and bracingly unsentimental — historical novel about the material and spiritual struggles of a Jesuit missionary to the Hurons in seventeenth century Canada.

Cold Heaven (1983) was the first Moore novel I read. That was over thirty years ago, and though the details faded over the decades, I retained a fairly strong memory of the theme and overall shape of the story. The impression that remained the strongest, however, was a feeling of general dislike. Because I very much enjoyed the subsequent Moore novels I read, I’ve often wondered whether my tepid response to Cold Heaven was my own fault; perhaps I just didn’t know how to read the book all those years ago. It was in this frame of mind that I recently reread the novel, reconfirming some of my original impressions and altering others.

Issues of faith and belief are central to all four of these books. Moore was raised a Catholic (and not just any Catholic — an Irish Catholic), though by the time he began his writing career he was no longer a believer. Though faith is a closed issue for most believers and non-believers alike — they’ve just come to different conclusions — for Moore the question is far from settled. Despite his rejection of his religious upbringing, in his books dealing with faith isn’t like picking up a lifeless broom handle — it’s like grabbing a snake. You can never be sure you’ve got a secure hold on it, and you have to adjust your grip constantly, because the thing you’re dealing with is alive, with a will of its own.

Before going any farther, a disclaimer — I am not a Roman Catholic, but I am a Christian, and though I am unable to entirely set aside my philosophical and theological convictions when I read a piece of fiction, I do make a good faith effort to take a writer’s work on his or her own terms. Given the subject of this book, I tried especially hard to assume as “neutral” a position as possible. I will say that Moore didn’t make that easy, which was probably his intention.

Cold Heaven is told (almost) entirely from the point of view of a young American woman in her mid-twenties named Marie Davenport. When the story begins, Marie is on vacation with her physician husband, Alex, in the south of France, where he is attending a medical convention. Marie has decided to leave Alex, an arrogant, controlling, selfish man, for her lover Daniel, whom she has secretly been having an affair with for over a year. Marie hasn’t yet summoned the courage to tell Alex this, however.

Before Marie can bring herself to confront her husband with her decision, Alex is struck by a motor boat while swimming in the Mediterranean and suffers a skull fracture. He is taken unconscious to a hospital, where he dies without ever regaining consciousness.

Things immediately shift from the tragic to the bizarre and inexplicable when Alex’s body disappears from the hospital. Has it just been “misplaced”, or is there something else going on? Marie begins to think the latter when she checks her hotel room and discovers that Alex’s clothing is gone and that someone has used his airline ticket to return to the states. Marie follows and catches up with this person, who turns out to be Alex, very much alive — sort of.

What happened? All Alex knows is that he woke up in the hospital morgue; confused and seized by panic, he fled the hospital and the country. When Marie finds him, he is wildly unstable; sometimes he seems almost normal, but most of the time he swings between combative agitation, and most frightening to Marie, a dull, glassy-eyed affectlessness when he seems little more than a zombie. Physically, his vital signs also go through extreme fluctuations; at times, his pulse and temperature readings are so low as to literally be impossible, and sometimes he seems to again be dead. Alex is apparently helplessly suspended between life and death.

Unwilling to abandon him in this condition, Marie wonders whether her husband is being used to punish her for something that happened a year before, and it is this mysterious event and Marie’s response to it that form the crux of the novel.

Exactly one year before Alex’s accident, Marie had been in Carmel, California for a tryst with Daniel. She had been taking a solitary stroll along the cliffs by the ocean when the figure of a young girl appeared lower down the cliff side, in a spot where it would have been virtually impossible for a person to be. Bathed in an eerie, unearthly light, the girl called Marie by name and told her, “I am your mother. I am the Virgin Immaculate.” She also instructed Marie to tell the priests of this encounter, because that spot must become “a place of pilgrimage.” These pronouncements were immediately followed by lightning and thunder, after which the figure faded away.

Such an experience would startle and discomfit almost anyone, but it especially shakes Marie, and for a very good reason — she’s an atheist who has nothing but hatred and contempt for religion and mistrust and suspicion for religious people.

Marie’s mother was a barely-practicing Catholic and her father wasn’t religious at all. When her mother died, Marie’s father put her into a Catholic boarding school in Montreal simply to have the girl out of his hair. She hated it there and never forgave her father for ignoring her pleas and abandoning her in a place that tried to indoctrinate her in an unwanted faith. (A convent of the same order as the despised school is in Carmel, near the spot where Marie saw the apparition.)

In the year between her experience in California and the disaster in France, Marie has gone about her life as if the vision never happened; not only did she not tell any priests about it, she has never told anyone else, either. She treats this possible encounter with the divine as if it were a shameful, dirty secret.

Alex’s accident and his strange condition coming exactly one year later — can it just be a coincidence? Marie thinks not; she very much fears that she is being punished for her disobedience, and that her husband is a kind of hostage, that through him she is being compelled to obey the apparition’s directions. She finally speaks to a sympathetic member of the Catholic clergy, Monsignor Cassidy, a cautious, commonsense religious bureaucrat who is nevertheless not insensitive to higher things. Marie’s main concern is not to be publicly implicated or involved in any way in this situation, whatever the church decides to do about it.

As Monsignor Cassidy tries to decide how to handle this situation (he would much rather be swimming or on the links) and Alex continues to lurch between extremes, Marie frantically tries to escape something that she can only think of as a trap; seeing herself as a victim of unseen forces, she suspects every word spoken, every action taken by anyone she meets as a move in a sinister chess game, the object of which is to steal her life from her. With a barely suppressed hysteria, she comes to see herself and everyone else in this drama as little more than powerless marionettes.

Her extraordinary dilemma is finally resolved when the apparition appears again, this time to a nun from the nearby convent. (Marie is present when this happens, but rather than see the vision again she closes her eyes, places her hands over her ears, and flings herself face down on the ground.) As the charge has now been “passed on” to someone else (due to Marie’s adamant refusal?), Monsignor Cassidy assures her that he will completely leave her out of the report that he will make to his superiors. She is free to resume her old life on her own terms.

People are sometimes spoken of as “clinging desperately” to belief; throughout the book, Marie has clung desperately to unbelief, and in the end, she has successfully outrun the Hound of Heaven. At one point, she declares (repeating Catholic doctrine, no doubt unintentionally), “a person has a right not to believe.” Monsignor Cassidy agrees: “I think God has let you go.”

It did not take long for me to remember why I felt a vague dislike when I thought of Cold Heaven — the reason is Marie; she’s a difficult character to warm up to, to say the least. We’re in her head for virtually the entire book, and for the whole course of the story, she’s driven by nothing but fear, hatred, anger, resentment, and suspicion that frequently crosses over into outright paranoia. Even if you think that these reactions are entirely understandable and justified, it’s still extremely unpleasant to be locked up with such a person for two hundred and fifty pages.

She’s also a frustrating character because the above-mentioned reactions and attitudes make her, quite literally, stupid. When she talks to the good-humored and reasonable Monsignor Cassidy or the friendly nuns from the convent, her preconceptions about them and her absolute refusal to concede that their worldview might have anything at all going for it, cause her to be almost literally unable to see them, unable to hear them, unable to understand the simplest things that they say to her, unable to extend them the smallest degree of trust or sympathy. (At one point, when she sees a minister in the hospital, she immediately bristles. She knows that there are always ministers around such places, “bothering people.” It never occurs to her that some people may actually want a minister, may benefit from their presence. If she were told that, she would likely stare blankly; the words wouldn’t even register.)

As she avoids the apparition’s directions, so she avoids any uncomfortable question or issue. She never once confronts the fundamental incoherence of her position, that of thinking that her husband is being threatened and that she’s being blackmailed by something that she doesn’t even believe exists. (Most of the time, she reflexively thinks that some unnamed “they” are forcing her to do what she doesn’t want to do. But exactly who are “they?” A golf-playing prelate and some dirt-poor nuns couldn’t be pulling the strings in a cosmic conspiracy, could they?)

We’re not much better off than Marie, because we never get a clear enough view of this struggle to be able to render a judgment on it — Marie seems to be just a recalcitrant piece of rope in a game of tug-of-war, the real nature of which we never understand, because we never know who’s holding the ends of the rope.

On a more down-to earth level, Marie never understands that she’s just like her hated father, who also would admit no impediments whatsoever to living his life precisely the way he wanted. Likewise, she avoids thinking about the irony of being desperate to save her husband… so that she can tell him that she’s leaving him because she never loved him. (After all, isn’t Alex as much a threat to the life Marie wants to live as any apparition?)

Still, despite its frequently infuriating protagonist, simply taken as an intricate, offbeat thriller, Cold Heaven is often a gripping read. If it ultimately feels somewhat unsatisfactory, that may be because of all the issues that are never addressed, the greatest of which is this — Marie “wins”, in that she successfully rejects the call that was placed on her (which, from everything that we can see, was a genuine one, not a dream, not a hallucination)… but in this context, what does winning mean? Has she really won a hard-fought victory, or has she actually suffered a defeat — one that may have eternal consequences?

That’s the question of questions, but a definitive answer to it can’t be given within the bounds of the story that Brian Moore has given us; perhaps one of the things that he was saying in Cold Heaven is that it’s a question that can’t be answered within the bounds of the “story” that we’re all in, this little life that begins in darkness and ends with a blank wall that it’s impossible to see over.

More now than after my first reading, though, I believe that Brian Moore was canny enough a writer to know what questions his book was posing but not answering, and also to know just what kind of impression Marie is likely to make on readers. I do wonder, though, if it might it not have been better to have given her some corner of herself, however small, that was beguiled — “tempted”, even — by the apparition’s call; it certainly would have made her a less strident, more interesting, more nuanced and sympathetic character. Moore almost certainly considered such a strategy, but we must assume that the Cold Heaven that would have resulted from that change is not the Cold Heaven he wanted to write.

In the end, it might be best to regard this odd, ambitious, unsatisfactory yet haunting novel as a sort of metaphysical nightmare. Some of my favorite books fall into this category — The Man Who Was Thursday by G.K. Chesterton, The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag by Robert A. Heinlein, The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien, The Land of Laughs by Jonathan Carroll, The Arabian Nightmare by Robert Irwin, Typewriter in the Sky and Fear by L. Ron Hubbard, The Mysterious Stranger by Mark Twain, UBIK by Philip K. Dick, and Conjure Wife by Fritz Leiber are some outstanding examples.

These are books in which the face of reality is veiled, and more than that, in which there is a strong implication that we can never pierce that veil, not because of any inherent limitations in our perception but because the appearance of things has been consciously contrived to deceive us. Contrived by whom? Ah, now that’s a question…

In a metaphysical nightmare, not only is there a sense that reality is inexplicable and sinister (that it’s somehow fundamentally wrong), but the characters must also have an overpowering feeling that they are trapped in that warped reality with no possibility of escape; that’s the nightmare aspect of the story. (The nightmares are literal in several of the books I mentioned, Fear and The Arabian Nightmare, especially, and even in Cold Heaven, where Marie begins having terrifying dreams after she first sees the apparition.)

Metaphysical nightmares are the very opposite of comforting, and reading one can give you a chill that can’t be dispelled by turning up the thermostat; certainly they’re not stories that you read for reassurance. Is the world really like that, though — are we actually living in a metaphysical nightmare? I don’t think so, but I know some people do. (I have to admit that there are days when it’s difficult to disagree with them.) I do know this, though — in a world like that, options are reduced to just a few: faith, despair, madness, or, as in the case of the triumphantly intransigent Marie Davenport, just lower your head, charge forward in your chosen direction, and whatever you do, avoid asking certain questions.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was To Save Your Sanity, Take Steven Leacock’s Nonsense Novels and Call Me in the Morning (or, Why Are Canadians Funny?)

7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend

Here are seven Author Shoutouts for this week. Find your favorite author or discover an…

The post 7 Author Shoutouts | Authors We Love To Recommend appeared first on LitStack.

SPFBO Finalist Review - Runelight by J.A. Andrews

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: JA Andrews lives deep in the Rocky Mountains of Montana with her husband and three children. She is eternally grateful to CS Lewis for showing her the luminous world of Narnia. She wishes Jane Austen had lived 200 years later so they could be pen pals. She is furious at JK Rowling for introducing her to house elves, then not providing her a way to actually employ one. And she is constantly jealous of her future-self who, she is sure, has everything figured out.

Find J.A. online: Website, Facebook, Twitter, Bookish Things Newsletter Signup with free short story

Runelight links: Amazon, Goodreads

ESMAY

You know, as much as I enjoy a wickedly inventive genre blender, sometimes all you need is some good ol’ traditional epic fantasy, and that is exactly what J.A. Andrews delivers in Runelight. Part rescue quest, part treasure hunt, this is a comfortingly familiar character-driven fantasy adventure full of mystifying mysteries and mystical magic.

Runelight is one of those books that just starts with a bang and has one hell of a strong hook. See, we follow a trio of young siblings as they stumble upon a mysterious aenigma box in a cave system, only to be devastatingly torn apart when their discovery attracts unwanted attention. Fast forward 20 years to now 32-year-old Keeper Kate, who has spent the past two decades hopelessly trying to solve the inexplicable mystery of the missing magic box and her lost brother… only for a surly elf to show up with that very same aenigma box and the shocking news that her other brother, Bo, has now vanished as well; cue the drama, mayhem, and adventure!

Now, even though the hectic and action-packed start was a bit overwhelming for me, I did really like how it set up the stakes and established the core motivations and relationships that drive this entire narrative forward. Plus, Kate immediately proved to be a very rootable protagonist, though I do have to say that she felt a bit immature (girlie did not read as early 30s to me) and kept grinding my gears with her tendency to speak her thoughts out loud to herself in the early parts of the book. Still, I was just beyond intrigued by all the mysteries going on in her life, be that the mystery surrounding the mystifying magic box, the fate of her disappeared brothers, the enigmatic shadow man following them all around, or any of the confounding trials and tribulations that she has to face on this dangerous mission.

Moreover, the side characters were also very likeable to me, even if they felt a bit stereotypical in their characterisation. See, for me Runelight just shines in its wholesome interpersonal relationships, and I was quite entertained by all the fun character dynamics amongst the little unlikely motley crew that Kate assembles to go on her rescue mission. There’s a good bit of snarky banter and light-hearted teasing between the idiosyncratic Kate, Venn the surly elf and Silas & Tribal the mischievous dwarves, and I really enjoyed seeing how they overcame their differences and prejudices to work towards their common goal.

All that said, I can’t sit here and pretend that Runelight was a smooth ride the entire way through for me. See, this book is quite a chunker, and I personally felt like the pacing was really hindered by some overly descriptive passages, a couple of very repetitive (internal) conversations and a frustrating lack of any satisfying answers/revelations for way too long. I mean, yes, I burned through this 700+ page book in just 3 days, but I think that was more because of the fact that Andrews’s prose is just so effortlessly readable than out of any real investment in the story or characters.

Ultimately though, it was just very nice and comforting to be back in the world of the Keepers that I had fallen in love with when I read The Keeper Chronicles a few years ago (oh how the little easter eggs made my heart smile!), even if Runelight never reached the heights of that series for me. If you like your fantasy to be character-driven, familiar, mysterious, adventurous, and full of heart, then I would recommend embarking on this epic journey.

ŁUKASZ

Runelight follows Kate, a Keeper (a storyteller-mage) on a quest to find her missing brother and the mysterious box linked to his disappearance. It starts strong - with mystery, high personal stakes, and a promise of adventure. It also delivers a female-led buddy adventure, which is cool, since epic fantasy rarely features platonic relationships between women. Kate forms alliance with Venn, a grumpy, emotionally scarred elf. It soon turns into a meaningful friendship. There’s no romantic tension, no enemies-to-lovers, just two women figuring out how to trust and fight alongside one another. For me, Kate and Venn’s friendship is the best part of the story. Set in the same universe as the author’s Keeper Chronicles, Runelight brings in familiar lore but has a different vibe. The tone is adventurous with an Indiana Jones-style flair. Puzzles, peril, ancient secrets, you name it. The antagonist remains mysterious, and it fits the story’s atmosphere of solving a long-buried mystery. But… I gotta be honest, this book felt way too long. Like, not just “epic fantasy long,” but bloated long. A lot of the middle felt repetitive - characters rehashing the same questions, Kate talking out loud to herself (a lot), and not much actual movement on the mystery front. I kept waiting for some big reveals or momentum to kick in, and instead the book kind of… wandered. And then, just when you think it’s building to something big, it pivots into a long flashback. That was a weird choice and kind of killed the tension. I also didn’t totally buy Kate as a thirty-something protagonist-she read way younger to me-and some of the worldbuilding leaned too heavily on characters sitting around explaining things to each other. There’s definitely cool stuff in the lore and magic system, but I wanted to experience it through the story, not just be told about it. Overall, Runelight had some really cool moments, but it dragged and left too much unresolved. Still, if you prefer heart and wit over blood and grit, chances are you’ll dig this one :) Also, the audiobook narrator does a great job!

OFFICIAL SPFBO SCORE

runelight.jpg)

Wolf Tracks - A Book Review by Voodoo Bride (reread/repost)

Wolf Tracks by Vivian Arend

Wolf Tracks by Vivian Arend(ebook, novella)

What is it about:

TJ Lynus is a legend in Granite Lake, both for his easygoing demeanor—and his clumsiness. His carefree acceptance of his lot vanishes, though, when his position as best man brings him face to face with someone he didn’t expect. His mate. His very human mate. Suddenly, one thing is crystal clear: if he intends to claim her, his usual laid-back attitude isn’t going to cut it.

After fulfilling her maid-of-honor duties, Pam Quinn has just enough time for a Yukon wilderness trip before returning south. The instant attraction between her and TJ tempts her to indulge in some Northern Delight, but when he drops the F-bomb—“forever”—she has second thoughts. In her world, true love is a fairytale that seldom, if ever, comes true.

Okay, so maybe staging a kidnapping wasn’t TJ’s best idea, but at least Pam has the good humour to agree to his deal. He’ll give her all the northern exposure she can stand—and she won’t break his kneecaps.

Now to convince her that fairytales can remake her world—and that forever is worth fighting for.

What did Voodoo Bride think of it:

Just as all the other Granite Lake Wolves novellas this story was fun, romantic and hot. It's the most fluffy of the first four novellas as it focuses mainly on the romance where the other stories have a bit of an action storyline going as well, but I can't say it bothered me and I really enjoyed this latest addition to this series. I do think if you aren't familiar with this series you can better read Wolf Signs first though as it will introduce you to TJ and it will make you love him even more than you will by reading this story on it's own. I do hope Arend will continue to write new stories in this series.

Why should you read it:

Clumsy sidekick finally gets the chance to show he's just as cool and sexy as the other wolves!

Notes on rereading:I'm doing my rereading out of order and can't remember everything from Wolf Signs. It does seem TJ is just as lovable if you've only read Wolf Games before diving into this one. I think if you read this as a standalone TJ might miss some of his clumsy charm that makes you already like him in the other books.

SPFBO Finalist Interview: J.A. Andrews, the author of Runelight

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: JA Andrews lives deep in the Rocky Mountains of Montana with her husband and three children. She is eternally grateful to CS Lewis for showing her the luminous world of Narnia. She wishes Jane Austen had lived 200 years later so they could be pen pals. She is furious at JK Rowling for introducing her to house elves, then not providing her a way to actually employ one. And she is constantly jealous of her future-self who, she is sure, has everything figured out.

Find J.A. online: Website, Facebook, Twitter, Bookish Things Newsletter Signup with free short story

Runelight links: Amazon, Goodreads

Thank you for agreeing to this interview. Before we start, tell us a little about yourself.

Hi! Thanks for inviting me! I’m Janice, and I live deep in the mountains of Montana, which I love. I’ve been an indie author for 8 years now, writing epic fantasy. All my trilogies are in the same world, and all are at least vaguely interrelated, although you can start with any of them that you like.

Including starting with Runelight.

Do you have a day job? If so, what is it?

Not one that pays! I homeschool my three teenagers and write.

Who are some of your favorite writers, and why is their work important to you?

My very favorite book (and one of the few non-fantasy books I read) is Pride and Prejudice, so Jane Austen is definitely a favorite of mine. She’s just so good at characterization and dialogue and subtext. I love her.

What do you like most about the act of writing?

This is a shockingly hard question. On any given day, writing might be either incredibly fun and feel like stepping right into my favorite world with fascinating people living an adventure—or it could be a painstaking effort to grind out every sentence.

Since that’s not an incredibly useful answer, I’ll add that dialog is by far my favorite part of writing.

Can you lead us through your creative process? What works and doesn’t work for you? How long do you need to finish a book?

I’ve discovered that I need to plan extensively before I write or I wander off course in the book and end up with an embarrassingly large amount of words that have to be cut out and left on the writing room floor.

I average one book a year, and even though every time I swear the next one will be faster, I have yet to make that a reality.

What made you decide to self-publish Runelight as opposed to traditional publishing?

I never have sought a traditional publishing contract. When I first looked into getting published, the traditional route felt so cumbersome that when I learned self-publishing was becoming a viable route, I jumped at the chance to have more control over the process. I’ve had such a positive experience self-publishing that I don’t currently have any interest in seeking out a traditional contract.

What do you think the greatest advantage of self-publishing is? And disadvantage?

The freedom to write the books I want and publish on the schedule I want. The disadvantage is that you don’t get the marketing power of the big publishers, and it’s a heckuva lot harder to get into bookstores.

Why did you enter SPFBO?

This was my 5th time entering SPFBO. I honestly hadn’t expected to reach the finals, but every year in the contest I’ve met great authors and bloggers and was excited to do the same this year. I think the community in SPFBO is the best part of the competition.

Your book is available in audiobook format. Can you share your experience producing it and a reflection if it was worth it?

I have the privilege of working with Podium to produce my audiobooks, and they provided me with amazing narrators. It’s been an excellent experience, and I’m so glad I did it.

How would you describe the plot of Runelight if you had to do so in just one or two sentences?

Indiana Jones meets classic epic fantasy. Two women embark on a rescue mission and find themself tangled in secrets and puzzles that are centuries old.

What was your initial inspiration for Runelight? How long have you been working on it? Has it evolved from its original idea?

After reading Michael J Sullivan’s Riyria series, I really wanted to write a similar thing with two female leads. Sort of a female buddy cop idea, because even though in life it’s very common for women to have deep, long-term friendships, I don’t see a lot of it in epic fantasy.

Runelight is set in the world of the Keepers, like my other books, and the main character Kate had already been introduced very briefly at the end of my Keeper Chronicles. I thought an Indiana Jones type adventure would be fun to write, and it has been! My original idea was more of a tone than a plot, so the book has stayed pretty faithful to that.

If you had to describe it in 3 adjectives, which would you choose.

Okay, I can’t seem to do this with adjectives, so I’m taking creative license and giving you three nouns. Found family, friendship, puzzles.

Is it part of the series or a standalone? If series, how many books have you planned for it?

It’s the first book in The Aenigma Lights Trilogy.

Who are the key players in this story? Could you introduce us to Runelight’s protagonists/antagonists?

Our protagonist is Kate, a Keeper (storyteller/mage) who’s searching for her brother who’s been missing for twenty years and the magical aenigma box that was connected to his disappearance. Along with her is Venn, an elf who has a decent amount of grump and a good deal of baggage. The two women go from enemies to besties while thrown neck-deep in secrets and mysteries that have spanned centuries.

The antagonist is…well, if Kate knew that, she’d be steps ahead of where she is. All she knows is a shadow–who might be kidnapping and murdering people–has apparently abducted (or killed?) her one remaining brother.

Does your book feature a magic/magic system? If yes, can you describe it?

Keeper magic involves moving energy from living things or fire, and manipulating it into heating other things or healing things or infusing things with life.

In a past life, I was an engineer, and this magic system involves the same sort of energy transfer we use on a daily basis, complete with massive inefficiencies and generally a lot of unnecessary heat generation.

Have you written the book with a particular audience in mind?

I write all my books for an adult audience who love classic epic fantasy tropes, but want them with a character driven, more modern feel.

I also write all my books so that my kids can read them at any age. So while they’re written for adults with adult characters and issues, there’s no graphic violence or language or sexual situations.

What’s new or unique about your book that we don’t see much in speculative fiction these days?

I think the idea of the central relationship being a friendship between women (which starts out more of a prickly forced companionship) is strangely rare in modern speculative fiction. I don’t tend to write much romance, but I do always end up with a lot of found family tropes in my writing. This, though, was the first time I just focused on a flat out friendship of a human mage and an elf, learning to respect and grow close to each other despite their differences.

Cover art is always an important factor in book sales. Can you tell us about the idea behind the cover of Runelight and the artist?

My artist is St. Jupiter, and it was really fun working with her to come up with symbolic artwork that could portray the mysterious runes that Kate deals with during the book.

What are you currently working on that readers might be interested in learning more about, and when can we expect to see it released?

I’m currently working on the final book in the trilogy, and the preorder date is set for summer of 2025!

Thank you for taking the time to answer all the questions. In closing, do you have any parting thoughts or comments you would like to share with our readers?

Thanks so much for having me! Fantasy Book Critic is such an integral part of SPFBO, I really appreciate getting the chance to hang out with you!

Women in SF&F Month: T. Frohock

Today’s Women in SF&F Month guest is T. Frohock! Her short fiction includes “Dark Places” (The NoSleep Podcast), “Every Hair Casts a Shadow” (Evil is a Matter of Perspective: An Anthology of Antagonists), “Love, Crystal, and Stone” (Neverland’s Library), and “La Santisima” (free on her website along with a couple others). She is also the author of Los Nefilim, a series of three historical fantasy novellas set in 1930s Spain, and Miserere: An Autumn Tale, an excellent character-driven dark fantasy […]

The post Women in SF&F Month: T. Frohock first appeared on Fantasy Cafe.Finding a Rhythm | Self-Discovery in “Dancing Woman” by Elaine Neil Orr

Orr’s Dancing Woman follows Isabel and her husband, Nick, over the course of 3 years…

The post Finding a Rhythm | Self-Discovery in “Dancing Woman” by Elaine Neil Orr appeared first on LitStack.

Teaser Tuesdays - In the Shadow of the Fall

The thought sent chills down her spine. Surely they knew what she was soon to do...

(page 9, In the Shadow of the Fall by Tobi Ogundiran

---------

Teaser Tuesdays is a weekly bookish meme, previously hosted by MizB of Should Be Reading. Anyone can play along! Just do the following: - Grab your current read - Open to a random page - Share two (2) “teaser” sentences from somewhere on that page BE CAREFUL NOT TO INCLUDE SPOILERS! (make sure that what you share doesn’t give too much away! You don’t want to ruin the book for others!) - Share the title & author, too, so that other TT participants can add the book to their TBR Lists if they like your teasers!

Let People Like Things

These winged beach rats have opinions. Image by Leila from Pixabay

These winged beach rats have opinions. Image by Leila from Pixabay

Good afterevenmorn!

Once again, there appears to be a lot of talk on the various socials about what is and isn’t good ‘art’ (writing, music and actual art) and who is “cringe” for liking what. Of course, for every declarative “cringe” thing, there is a considerable amount of pushback from the folks who like that thing. Heavens, it’s all so very tiresome.

I know I’ve ranted about this, but the proliferation of this nonsense in the past couple of weeks has inspired to repeat myself. Yet again.

I have variously seen angry rants about Sleep Token (a genre-defying band that enjoyed a meteoric rise in the past couple of years), romance novels, fantasy novels, science fiction novels, horror novels, literary fiction, anything in the Warhammer universe, My Little Pony nonsense (yes, even after all this time), and even someone who decided that it’s cliché, boring and stupid for young women to love horses.

Good lord.

Just let people like things.

I can’t believe I have to say this again in the year two thousand and twenty-five.

This Canadian cobra chicken is going to make themselves heard, damn it. Image by Lo Age from Pixabay.

This Canadian cobra chicken is going to make themselves heard, damn it. Image by Lo Age from Pixabay.

While this is covering a broad list of things that I saw this week, it is especially pertinent for speculative fiction. So many people in speculative fiction try to make themselves feel better about their preferred genre by being absolutely horrendous to other folks for no other reason than their own enjoyment of a different genre. It’s the dumbest thing I have ever personally witnessed.

Listen, everyone is perhaps a little wound-up at present. Perhaps that’s why some folks are overblowing small, personal tastes and attempting to shame or belittle anyone who happens to think differently. I get it. I’m pretty irritable at present, too. Things are less than fun for most people at the moment. If you find yourself getting irrationally irate at a particular take, I’m going to offer you a plan of action.

Ready? Let’s begin.

So, someone likes something you don’t

Before posting your rebuttal, go through this short checklist:

1. Does their liking something you do not materially affect your life at all?

If their obsession with Warhammer 40K intrudes only on your timeline and not in any other part of your life, your best course of action is to simply scroll past and leave them alone.

Now if it is doing some material, genuine harm to you and your life, then yes, feel free to discuss that. It’s rare, but I absolutely do agree that it does happen, and it should be brought to light. But if the only thing wrong with the thing is that you don’t personally like it, just scroll on.

2. Are you perhaps a little hungry?

Suffering from caffeine or nicotine withdrawal? Hold off publicly berating someone for their tastes in science fiction novels or for enjoying romance. Oh, they’re 20 years late to The Lord of the Rings, and you’re so over it? Go eat something. Have a nap. It’s alright. Everything will be a little better when you wake up.

Baby.

3. Did anyone actually ask you?

Was your opinion requested, or were they just sharing something that was giving them joy? If you were asked, by all means tell them your thoughts. Otherwise, hush. No one asked you. Believe it or not, most people couldn’t care less that you believe Sleep Token “isn’t real metal” and “is so overrated,” for example. I doubt anyone who loves fantasy as a genre cares whether or not you find it “irrelevant” and “without intellectual merit.” No need to reply to that tweet of theirs. Just scroll on. And just like that, you’ve not crushed anyone, or ruined a joyous moment, or put something unnecessarily negative out in the world for no reason but to soothe your own misplaced ire.

I know, I know. You think that it’s just so dorky. And? I don’t agree, but let’s pretend it’s objectively so very nerdy in the worst possible way. So what? Let them be a dork. Even publicly. You needn’t bother yourself with correcting them. After all, if it’s true, they’ll just be ignored, and all sad and alone. You’ll be vindicated without so much as lifting a finger. How lovely. And if they’re not ignored, but find a community 0f like-minded folks, even better. Now you’ll be spared from having to deal with all those dorks. They’ll take care of themselves in their own little corner. Go you.

This swallow needs the world to know her thoughts. Image by Kev from Pixabay.

This swallow needs the world to know her thoughts. Image by Kev from Pixabay.

Are you struggling to contain your rebuttal? That’s alright. We’ve all been there. Here’s a possible solution: Write it out. Write in your journal. Or on a blog post (waves). Hell, even make it a Twitter thread. Just don’t @ the person who inspired your tirade, or do it as a linked reply or quote. That way you can vent your weaselly black guts out without ruining anyone else’s day. You’ll feel better, and they’ll be blissfully unaware.

We all need to vent sometimes. That’s alright. Do that.

But I do not, never have, and never will understand the impulse to be horrid to someone sharing a thing that brings them joy just because they shared the thing that brought them joy and it doesn’t bring you joy. Let people like things. Even things you don’t like. The world won’t end. I promise.

When S.M. Carrière isn’t brutally killing your favorite characters, she spends her time teaching martial arts, live streaming video games, and cuddling her cat. In other words, she spends her time teaching others to kill, streaming her digital kills, and a cuddling furry murderer. Her most recent titles include Daughters of Britain, Skylark and Human. Her serial The New Haven Incident is free and goes up every Friday on her blog.

Book review: The Book That Held Her Heart by Mark Lawrence (The Library Trilogy # 3)

Mark Lawrence has never been one to pull punches, and The Book That Held Her Heart might just deliver his most merciless finale yet. Everything that made The Library Trilogy special (an ambitious blend of mystery, adventure, and philosophical musing) collides violently, and with lots of powerful twists.

This time, the stakes are cataclysmic. The fate of the infinite library hangs by a thread, and Livira and Evar, once inseparable, are scattered across time. Livira is chasing answers through the labyrinthine past, while Evar is trapped in an impossible situation, kept alive through means best left unspoiled. Meanwhile, the war over the library rages on, with no simple resolutions is sight.

The Book That Held Her Heart feels darker and weightier that its predecessors. Not just in terms of stakes - though those are plenty brutal - but in its themes. The story brings in a new perspective through Anne Hoffman, a Jewish girl in Nazi Germany, tying the library’s war to the real-world horrors of book burning and historical erasure. It’s a bold move, and Lawrence makes it land. I feel the incorporation of real-world history into already mind-bending worldbuilding was a gamble, but it payed off. Ultimately, the story that has always been about books, memory, and the battle between knowledge and ignorance.

Despite the weighty themes (censorship, history’s cyclical nature, and the cost of knowledge) the novel never drags. Lawrence balances it all with his trademark wit and clever chapter epigraphs. The ending is powerful and I needed a moment to process it.

The Book That Held Her Heart is a stunning, gut-punch of a conclusion. It demands patience, rewards rereads, and cements Lawrence as one of the genre’s most daring storytellers.

Book Review: The Notorious Virtues by Alwyn Hamilton

I received a review copy from the publisher. This does not affect the contents of my review and all opinions are my own.

The Notorious Virtues by Alwyn Hamilton

The Notorious Virtues by Alwyn Hamilton

Mogsy’s Rating: 4.5 of 5 stars

Genre: Fantasy

Series: Book 1 of The Notorious Virtues

Publisher: Viking Books for Young Readers (April 1, 2025)

Length: 320 pages

Author Information: Website | Twitter

After years of hanging out on my Goodreads not-yet-released shelf, The Notorious Virtues, I have to say, was well worth the wait. Even though it’s been quite a while since I read Rebel of the Sands, Alwyn Hamilton clearly still has what it takes to deliver the first book of a riveting, character-driven saga that thrills with rich world-building and a high stakes plot. The story had me hooked from page one, and I want more!

Told through the eyes of four main characters, the author transports us to the glittering city of Walstad where magic talks and where you come from means everything. No one understands this more than Honora “Nora” Holtzfall, who is born into one of the richest families, comfortably in line to inherit all her grandmother’s power and riches—that is, until her mother’s brutal murder throws the line of succession into jeopardy. Now Nora finds herself thrust back into a series of vicious Veritaz trials in which she must compete with her cousins for the right to become the Holtzfall heir. But to everyone’s surprise, an extra challenger has been added to the roster in the form of Ottoline “Lotte” Holtzfall, allegedly a long-lost member of the family who has been raised secretly at a convent. Confident in her skills and intelligence, Nora isn’t threatened at all by this newcomer, but unbeknownst to her, Lotte actually possesses one of the rarest, most powerful magical abilities found in the Holtzfall family bloodline.

Meanwhile, Nora has not forgotten what had set everything in motion in the first place and is determined to find her mother’s killer. The press has already all but named the Grimms as culprits, since the resistance group is known to target the aristocracy in their fight to achieve more equality between Walstad’s disparate classes. However, Nora is not convinced, and neither is August, a skeptical journalist who believes the murder was more than just a mugging gone wrong. Forming a tenuous alliance, the two of them set out to find the truth. And finally, we have Theo, our fourth POV character and a member of the Rydder Knights—an ancient order magically bound to serve the Holtzfall family ever since the first knight swore a sacred oath centuries ago. But over time, that relationship has begun to erode, and what was meant to ensure protection has been twisted into something more troubling, like forced obedience. Through Theo’s eyes, we see the cracks of that legacy in his struggle to decide whether to do his duty or to stand by his brother, the bodyguard of Nora’s mother, who has been missing since the night of her murder.

Where do I even start? There’s so much going for The Notorious Virtues, but I think I’ll have to begin with the characters because without them, this book wouldn’t have been anywhere near as impressive. Nora is one of our four main POVs, but as much as I enjoyed the others, I feel it’s only right to spotlight her in my review. Not only is she a favorite, she alone ties the whole story together. While she may cultivate her spoiled and empty-headed rich brat persona, she is in fact very intelligent and introspective, leading her enemies—and readers—to underestimate her. And even though she may come across as arrogant and proud of her own smarts and talents, it’s hard to hold that against her when that pride is well deserved. At the end of the day, it’s refreshing to read about a confident young woman who is comfortable in her own skin, and later, she earns even more points by using that charisma to try to make Walstad a better place for all.

Then, there’s the plot. Finally, a YA novel that isn’t on rails and utterly predictable right out of the gate. That isn’t to say The Notorious Virtues uses completely new ideas, but wherever it borrows ideas from well-tread territory, it at least tries to do something different and unique with them. It helped that there were multiple POVs, and that each character represented a very different way of life in Walstad. As a result, each of them also had very different motivations, keeping the story interesting. Then there was the political backdrop and the social divisions, with the Hottzfall family at the center looming over all the other districts. Thematically, this led to a thoughtful exploration of wealth, privilege, and status—how these forces shape societal power structures, especially in a world where magic tends to be inherited and often weaponized to maintain control. Even as the Veritaz trials took center stage, I found myself equally captivated by the larger conflicts brewing beneath the surface, such as the rise of the Grimms and their radical resistance against the Holtzfall dynasty.

At the end of the day, I had a great time reading The Notorious Virtues. My only gripe might be that a couple of the main POVs, especially Theo’s, might need a little more attention to bring them up to a similar level of characterization as Nora or Lotte. But overall, I loved the story, I loved the setting, and I particularly enjoyed the writing. All of it was surprisingly in-depth and well-crafted for a YA novel, but it was also clear Alwyn Hamilton put a lot of care into making it a reality. I’m glad that all her time and work paid off. Looking forward to more in the series.

![]()

![]()

The Sanguine Sands (The Sharded Few #2) by Alec Hutson (reviewed by Mihir Wanchoo)

Order The Sanguine Sands over HERE

Read Fantasy Book Critic's review of The Crimson Queen

Read Fantasy Book Critic’s review of The Umbral Storm

Read Fantasy Book Critic’s review of The Book Of Zog

Read Fantasy Book Critic's interview with Alec Hutson

Read TUS Cover Reveal Q&A with Alec Hutson

Watch ATFB Interview with Alec Hutson

Watch TBOZ & TUS Video interview with Alec Hutson

AUTHOR INFORMATION: Alec Hutson was born in the north-eastern part of the United States and from an early age was inculcated with a love of reading fantasy. He was the Spirit Award winner for Carleton College at the 2002 Ultimate Frisbee College National Championships. He has watched the sun set over the dead city of Bagan and rise over the living ruins of Angkor Wat. He grew up in a geodesic dome and a bookstore, and currently lives in Shanghai, China.

OFFICIAL BOOK BLURB: The Heart of the Heart has been found.

In the ruined palace of the Radiant Emperor the Light shard had been hidden for a thousand years, but now a sliver of its power has entered the flesh of Heth Su Canaav. Once Hollow, he has been reborn as one of the Sharded Few. Its discovery will shake the world . . . if anyone lives to tell of its existence.

For hunters stalk the refugees from the Duskhold. Powerful Sharded, unnatural sorcerers, and creatures that they cannot yet comprehend. Deryn and Heth must flee to the ancient city of Karath, where they hope answers await about who was behind the attempt to murder Rhenna Shen, and why one of the mysterious Elowyn directed them to find the House of Last Light.

The north lurches towards war, Shadow and Storm closing around the flickering Flame, while the Blood scheme in the black ziggurats of the Sanguine City, and far away something stirs in the frozen wastes where the disciples of Ice cling to an ancient faith . . .

CLASSIFICATION: The Sharded Few saga is a unique mix of The Way of Kings and Blood Song as it provides the epic world & magic system of Brandon Sanderson’s magnum opus while also providing the character rich story found in Anthony Ryan’s debut.

FORMAT/INFO: The Sanguine Sands is 528 pages long divided over forty-five POV titled chapters with a prologue and an epilogue. Narration is in the third person via Deryn, Heth Su Canaav, Alia, Kaliss & a singular POV chapter (titled the Cleric). This is the second volume of the Sharded Few series.

April 7th, 2025 marked the e-book publication of The Sanguine Sands and it was self-published by the author. Cover art is by YAM (Mansik Yang) and design-typography by Shawn T. King.

OVERVIEW/ANALYSIS: I’ve been besotted with this world and story since Alec Hutson first granted me an ARC of The Umbral Storm. The first book was an incredible start and it was my favourite book of 2022 alongside being FBC’s SPFBO Finalist selection. The author had gone through very trying personal situations and that’s the major reason for the 3 year wait between TUS and its sequel. But here we are and when The Sanguine Sands landed in my inbox, I was overjoyed as I couldn’t wait to see how the author upped the magnificent story that was The Umbral Storm.

The Sanguine Sands opens up with a prologue wherein we get to see a further corner of the world and within it a very creepy monastery with a wild interior design. I believe the timing of the prologue corresponds to the latter half of TUS. The story opens with our POV characters Alia, Deryn, Heth and lady Rhenna as they are the only survivors of the assassination attempt. However Alia and Heth are not longer just “hollow”. They have now newer aspects to themselves and have been given a path towards the free city of Karath. Wherein they must find the House of Last Light and learn more about the mysteries of the world. However they also have to lay low while making the journey as Rhenna wishes to know who truly was behind the assassination attempt. All of this and more machinations abide in this thrilling sequel which ups the ante in every department.

Let me state the obvious, I was a huge fan of the first book and hence one might wonder how objective my review can be. Let me assure you, I was very apprehensive about this sequel as anticipation can often kneecap one’s favourites more than anything else. Alec had also written a different fantasy title in between (The Pale Blade) this series and that meant he was returning almost 3 years to this sequel. I was so wrong about having to worry as I can safely shout that this book is triply magnificent.

Once again the worldbuilding shines as we get more knowledge about the various Sharded holds but also about various geographical aspects of the world and get a nautical journey as well. The author also illuminates other races that are present in the world and here I must highlight the author’s love for turtles within his books (you’ll know when you see it).

This book outdoes its predecessor in one more aspect, TUS’s start was said to be a bit on the slower side by some but here there’s no slowing down at all, from the moment the foursome start their journey towards Karath to the exciting climax, the plot pace is ever engaging. Another plus point in the characterization and herein the trio of Alia, Deryn & Heth get more to do. Alia particularly also gets more chapters than in the first volume. Plus one of my favourite secondary characters from the first book Kaliss gets a POV turn and her chapters are even more action-packed than the rest of the book.

The character work has to be lauded as we get to see all three of our POV characters break out of their mould and learn to adapt to new (& frankly scary situations). I enjoyed how the author is allowing these young characters to age into the adults they will becoming. Alec Hutson is a person who knows how to keep the readers enticed with his characterization and this series is another fine example of it.

This book similar to the first one is absolutely filled to the brim with worldbuilding and within this sequel we get to know more of the world’s history, theological past and magic system workings. I can’t reveal more because they are all huge spoilers but safe to say, most if not all of my curiosities (as spoken with Alec in our interview) were answered. I LOVED this aspect as it made the worlbuilding junkie go gaga. Lastly the ending was just perfect, it ends the story so precisely and with such a tantalizing premise that I felt the climax was better than its predecessor.

For me, there were only two minor complaints about this book. First that it ends on such a tantalizing note and now we have to wait until the third book releases to find out what happens next. Secondly I think the author kept the story with a very tight focus on the main POV characters. I thought that there was a possibility that if we could have seen more of the events in the north and it would added to the epicness of the story. However that would also detract from the plot’s tightness and maybe I would be complaining otherwise.

CONCLUSION: The Sanguine Sands is a sequel that made even a bigger fan of Alec Hutson, epic worldbuilding and fantastic characterization have been Alec’s forte but this series of his is turning out be his best one yet. If you love epic fantasy then you can’t miss out on The Sharded Few saga.

Free Fiction Monday: Sob Sisters

Madison, Wisconsin, 1972—When Detective Hank Kaplan calls Valentina Wilson to a crime scene, she wonders why. She soon finds more questions than answers in a secret room belonging to a wealthy female philanthropist, whose brutal murder the police hastily cover up. Val’s search for the truth will take her from the rape hotline she runs to the shocking realization that the woman’s murder anchors a long line of horrific events stretching back decades.

Chosen as one of the best mystery short stories of the year by the readers of Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, “Sob Sisters” continues the powerful story of Valentina Wilson, a character who first appeared in Nelscott’s award-winning Smokey Dalton series.

“Sob Sisters“ is available for one week on this site. The ebook is also available on all retail stores, as well as here.

Sob Sisters By Kris Nelscott

TECHNICALLY, I WASN’T supposed to be at the crime scene. I wasn’t supposed to be at any crime scene. I’m not a cop; I’m not even a private detective. I’m just a woman who runs a rape hotline in a town that doesn’t think it needs one, even though it is 1972.

Still, what woman says no when she gets a phone call from the Madison Police Department, asking for her presence at the site of a murder?

A sensible one, that’s what my volunteers would have said. But I have never been sensible.

Besides, the call came from Detective Hank Kaplan who, a few months ago, had learned the hard way to take me seriously. Unlike a lot of cops who would’ve gotten angry when a woman out-thought him, Kaplan responded with respect. He’s one of the new breed of men who doesn’t mind strong women, even if he still has a derogatory tone when he uses the phrase “women’s libbers.”

The house was an old Victorian on a large parcel of land overlooking Lake Mendota. Someone had neatly shoveled the walk down to the bare concrete, and had closed the shutters on the sides of the wrap-around porch, leaving only the area up front to take the brunt of the winter storms.

And of the police.

Squads and a panel van with the official MPD logo on the side parked along the curb. I counted at least four officers milling about the open door while I could see a couple more moving near the large picture window.

I parked my ten-year-old Ford Falcon on the opposite side of the street and steeled myself. I was an anomaly no matter how you looked at it: I was tiny, female and black in lily-white Madison, Wisconsin. Most locals would’ve thought I was trying to rob the place rather than show up at the invitation of the lead detective.

I grabbed the hotline’s new Polaroid camera. Then I got out of the car, locked it, and walked as calmly as I could across the street. I wasn’t wearing a hat or gloves, so I stuck my hands in the pocket of my new winter coat. At least the coat looked respectable. My torn jeans, sneakers, and short-cropped Afro were too hippy for authorities in this town.

As I approached, a young officer on the porch turned toward me, then leaned toward an older officer, said something, and rolled his eyes. At that moment, Kaplan rounded the side of the house and caught my gaze.

He hurried down the sidewalk toward me. He was wearing a blue police coat over his black trousers and galoshes over his dress shoes. Unlike the street cops on the porch, he didn’t wear a cap, leaving his black hair to the vicissitudes of the wind. He was an uncommonly handsome man, with more than a passing resemblance to the Marlboro Man from the cigarette ads. I found his good looks annoying.

“Miss Wilson,” he said loud enough for the others to hear, “come with me.”

He sounded official. The cops outside started in surprise, then gave me a once-over.

A shiver ran down my back. I hated the scrutiny, even though I knew he had done it on purpose, so no one would second-guess my presence here.

“This way,” he said, and put a hand on my back to help me up the curb.

I couldn’t help it; I stiffened. He let his hand drop.

“Sorry,” he said. He knew I had been brutalized by a cop in Chicago. While that experience had made me stronger, I still had a rape survivor’s aversion to touch.

“What’s going on here?” I asked.

“I’ll show you,” Kaplan said. “But we’re going in the back. Did you bring your camera?”

I held up the case. I had wrapped the strap around my right hand.

“Good,” he said. “Come on.”

He walked quickly on the narrow shoveled sidewalk leading around the building. I had to hurry to keep up with him.

“So,” I said, as soon as we were clear of the other cops, “you guys don’t have your own cameras?”

“We do,” he said. “You’ll just want a record of this.”

Now I was really intrigued. A record of something that he was willing to share; a record of something that they didn’t want to record themselves? Maybe he had finally decided that I should photograph a rape victim immediately after the crime had occurred.

Although Kaplan didn’t handle the rape cases. He was homicide.

The narrow sidewalk led to another small porch. Kaplan pulled on the screen door, and held it for me. Then he shoved the heavy interior door open.

A musty smell rose from there, tinged with the scent of fall apples. I had expected a crime-scene smell—blood and feces and other unpleasantness, not the somewhat homey smell.

To my right, half a dozen coats hung on the wall, with a variety of galoshes, boots, and old shoes on a plastic mat. This was clearly the entrance that the homeowner used the most.

“When should I start photographing?” I asked.

“I’ll tell you when,” Kaplan said, and led me up the stairs.

We stepped into a kitchen that smelled faintly of baked bread. I frowned as Kaplan led me through swinging doors into the dining area. A picture window overlooked the lake. The view, so beautiful that it caught my attention, distracted me from the coroner’s staff, who clustered in the archway between the dining room and living room.

Kaplan touched my arm, looking wary as he did so. I glanced down, saw an elderly woman sprawled on the shag carpet, arms above her head, face turned away as if her own death embarrassed her. This area did smell of blood and death. The stench got stronger the closer I got.

I couldn’t see her face. One hand was clenched in a fist, the other open. Her legs were open too, and looked like they had been pried that way. A pair of glasses had been knocked next to the console television, and a pot filled with artificial fall flowers had tumbled near the door.

The coroner had pulled up the woman’s shirt slightly to get liver temperature. The frown on his face seemed at once appropriate and extreme for the work he was doing.

I moved a step closer. He looked up, eyes fierce. His mouth opened slightly, and I thought he was going to yell at me. Instead, he turned that look on Kaplan.

“Who the hell is that? Control your crime scene, man. Get the civilians out of here.”

“Sorry,” Kaplan said, sounding contrite. “I turned in the wrong direction.”

He touched my arm to move me away from the crowd. I realized that he had play-acted to convince the coroner and the other police officers that my appearance in that room had been an accident.

But it hadn’t been. Kaplan had wanted me to see the body.

“This way,” he said in that formal voice, as if he thought someone was still listening.

He led me back into the kitchen, then opened a door into a large pantry. Canned goods lined the walls. A single 40-watt bulb illuminated the entire space.

My stomach clenched. I had no idea what he was doing, and I wasn’t the most flexible person around cops.

He pulled the pantry door closed, then moved past me and pushed on the far wall. It opened into a book-lined room with no windows at all. Mahogany shelves lined the walls. The room was wide, with several chairs for reading and a heavy library table in the middle, stacked with volumes. Those volumes were half open, or marked with pieces of paper.

Beyond that was another open door. Kaplan led me through it.

We stepped into one of the prettiest—and most hidden—offices I had ever seen. The walls were covered with expensive wood paneling. A gigantic partners desk sat in the middle of the room. The flooring matched the paneling—no shag carpet here. Instead, the desk stood on an expensive Turkish carpet, of a type I had only seen in magazines. The room smelled of old paper, books, and Emerude. I couldn’t hear the officers in the other part of the house. In fact, the only sound in this room was my breathing, and Kaplan’s clothes rustling as he moved.

An IBM Selectric sat on the credenza beside the desk. Behind it stood a graveyard of old typewriters, from an ancient Royal to one of the very first electrics. Above them, files in neat rows, with dividers. The desk itself had several open files on top, and a full coffee cup to one side. I wanted to touch it, to see if it was still warm.

“This is what you wanted to show me?” I asked.

“I think you’ll find some interesting things here,” he said, nodding toward the floor. Against the built-in bookshelves in a back corner, someone had placed dozens, maybe hundreds of picture frames.

I crouched. Someone had framed newspaper and magazine articles, all of them from different eras and with different bylines.

“What is this?” I asked.

“Her life’s work,” he said.

“Her,” I repeated. “I’m not even sure whose house this is.”

He looked at me in surprise. “I thought you knew everything about this town.”

“Not even close,” I said.

He sighed softly. “This house belongs to Dolly Langham.”

“The philanthropist?” I asked.

He gave me a tight smile. “See? You do know her.”

“I don’t,” I said. “Some of my volunteers kept trying to contact her for help with fundraising for the hotline, but she never returned our calls or our letters.”

A frown creased his forehead. “That’s odd. She was always doing for women.”

I frowned too. “I take it she’s the woman in the living room?”

“That’s the back parlor,” he said, as if he knew this house intimately. Maybe he did.

“All right,” I said slowly, not sure of his non-response. “The back parlor then. That’s her?”

He closed his eyes slightly and nodded.

“You’ve caught this case?” I asked. “It’s yours entirely?”

“Yeah,” he said, and he didn’t sound happy about it. “This is a big deal. Miss Langham is one of the richest people in the city, if not the richest. Her family goes back to the city’s founding, and she’s related to mayors, governors, and heads of the university. She’s important, Miss Wilson.”

“I’m getting that,” I said. “Why am I here?”

“Because,” he said, “cases like this, they’re always about something.”

“Yes, I know, but—”

“No,” he said. “You don’t know. There’s the official story. And then there’s the real story.”

I froze. Cops rarely spoke to civilians like this. I had learned that from my ex-husband, who had been a Chicago cop and who had died, in part, because of what had happened to me.

“You think the real story is going to get covered up,” I said.

“No,” Kaplan said. “I don’t think it. I know it.”

I glanced around the room. “The real story is here?”

He shrugged. “That I don’t know. I haven’t investigated yet.”

He was being deliberately elliptical, and I was no good with elliptical. I preferred blunt. Elliptical always got me in trouble.

“Why am I here?” I asked.

“I need a fresh pair of eyes,” he said.

“But the investigation is just starting,” I said.

He nodded. “So is the pressure.”

I let out a small breath of air. So, he had a script already, and he didn’t like it. “You want me to photograph things in here?”

“As much as you can,” he said. “Keep those pictures safe for me.”

“I will,” I said.

“And Miss Wilson, you know since you were once a cop’s wife, how things occasionally go missing from a crime scene?”

“Oh, I do,” I said. “You want to prevent that here.”

He shook his head, and gave me a look he hadn’t shown me since the first time I met him. The look accused me of being naïve.

“You know, Miss Wilson, I find it strange that you don’t carry a purse. Most women carry bags so big they can fit entire reams of paper inside them.”

My breath caught as I finally understood.

“I prefer pockets,” I said, and stuck my hands inside the deep pockets of my coat.

“You are quite the character, Miss Wilson,” he said approvingly. “I think you might have a couple of uninterrupted hours in here, if I keep the doors closed. Is that all right with you?”

Inside a room with no windows, only one door, a phalanx of cops outside, and a dead body a few yards away. Sure, that was Just Fine.

“You’ll be back for me?” I asked.

“Most assuredly,” he said, and put his hand on the door.

“One last thing, Detective,” I said. “Who found this room?”

A shadow passed over his face, so quickly that I almost missed it. “I did. No one else.”

So no one else knew I was here.

“All right,” I said. “See you in two hours.”

He nodded once, then let himself out, pulling the door closed behind him.

I felt claustrophobic. This room felt still, tense, almost as if it were waiting for something. Maybe that was the effect of the murdered woman in the back parlor. Maybe I was more tense than I thought.

That would be odd, though. I had training to keep me calm. I went to medical school until I couldn’t find a place to intern (honey, we don’t want you to take a position away from a real doctor), and then I went to the University of Chicago Law School. I got used to cadavers in medical school, and extreme pressure in law school, and somewhere along the way, I had accepted death as a part of life.

I let out a small sigh, squared my shoulders, and pulled off my coat. I opened it, so that the inner pockets were easily accessible, and draped it on one of the straight-backed chairs near the door. Then I grabbed the Polaroid and put it around my neck.

I didn’t know where to start because I didn’t know what I was looking for. But Kaplan had asked me here for a reason. He wanted me to find things, and to remove some of them, which meant that I shouldn’t start with the books or even the framed articles.

I started with the files.

I walked behind the desk. The perfume smell was strong here. Dolly Langham had clearly spent a lot of time at this desk. The papers on top were notes in shorthand, which I had never bothered to learn. I was certain one of my volunteers at the hotline knew it, however. I stacked those papers together and put them in a “Possible” pile. I figured I’d see what I found, and then stash what I could just before Kaplan came back for me.

I opened the drawers next. The top held the usual assortment of pens and paperclips, and stray keys. The drawer to my right had a large leather-bound ledger in it.

The ledger’s entries started in 1970, and covered most of the past two years. The most recent entry was from last week. There were names on the side, followed by a number (usually large) and a running total along the edge. That much I could follow. It was the last set of numbers, one column done in red ink and the other in blue, that I couldn’t understand.

Kaplan had to know this was here. He had to have looked through the desk; any good investigator would have.

I took the ledger and placed it on my coat.

Then I went back and searched for more ledgers. I figured if she had one for the 1970s, she had to have some from before that. I didn’t find any in the drawer—although I found a leather-bound journal, also written in shorthand, with the year 1972 emblazoned on the front.

I set that on the desktop along with the notes, and continued my search.